Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 303

September 12, 2017

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray resigns amid new sexual abuse allegations

(AP Photo/Elaine Thompson, File) (Credit: AP)

On Tuesday morning, only hours after he was publicly accused of sexually abusing his younger cousin, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray announced he would resign.

Murray’s resignation will go into effect at 5 p.m. on Wednesday, the Seattle Times reported.

“While the allegations against me are not true, it is important that my personal issues do not affect the ability of our City government to conduct the public’s business,” Murray said in a statement, the Times reported.

Mayor Murray was elected to office in 2013, and was formerly a Democratic state legislator.

Murray’s cousin, Joseph Dyer, 54, became the fifth person to accuse him of sexual abuse. Dyer said Murray, 62, forced him to have sex at the age of 13, while the two lived in Dyer’s mother’s home in New York, according to the Times.

Lloyd Anderson, another man who has accused Murray of sexual abuse, released a statement through his attorney in which he expressed empathy for other alleged victims. “I feel victory, but saddened that it required another victim to come forward for him to resign. I wonder how many other victims are out there,” the statement said, according to the Times.

Murray, who ended his re-election bid earlier in the year due to the scandals, has denied all of the allegations, and indicated that the most recent accusations stemmed from “bad blood between two estranged wings of the family,” the Times reported.

As for future leadership in Seattle, city Councilmember Bruce Harrell will step in as mayor and will decide within five days if he will finish out Murray’s term or not, the Times reported.

“God, sex, scatological”: Why nearly every culture has its own “very bad words”

One of the great unifying bonds of human nature is our eternal fondness for swearing. Across a wide swath of languages and cultures, people love a well-lobbed expletive. “God, sex, scatological. Simple as that,” Matt Fidler, the creator and host of the “Very Bad Words” podcast told me on “Salon Talks.” “Pretty much all cultures have swear words regarding all of those. And they vary in nature depending on the context of that culture.”

Fidler’s inspiration for the podcast evolved out of an early episode of the FX comedy “Louie,” in which a gaggle of comics discussed the etymology of an anti-gay slur. I thought, “That’s fascinating. Is there a podcast about this?” he recalled. “There was never a show just dedicated to swearing.”

The show, which launched in July, consciously chose to set its tone with a debut segment on the complex meanings we assign to the word “shit.” Fidler said, “It’s one of the most commonly said words. It’s really old; it’s been around for over a thousand years. Almost every language has a taboo word for shit. Shit is so fundamental. It’s the first thing we do. Kids understand shit immediately.”

And although in subsequent episodes “Very Bad Words” has delved into more hot-button words and subjects, the purpose is never mere bleep-worthiness, but to educate and help people understand why language can evoke such passion. “This is not an obscene show,” Fidler said. “It’s not a gross show. I don’t try to shock people; I don’t try to offend people — though that inevitably happens sometimes.”

Watch our full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook.

Tune into “Salon Talks” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET /1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

Edith Windsor, gay-rights activist and marriage-equality icon, dies at 88

Edith Windsor in front of the Supreme Court (Credit: AP/Carolyn Kaster)

Edith Windsor, the gay-rights activist whose historic Supreme Court case ended the Defense of Marriage Act, died Tuesday. She was 88 years old. Windsor’s death was confirmed dead by her wife Judith Kasen-Windsor, the New York Times reported. The couple were married in 2016.

But it was Windsor’s first marriage to Thea Spyer in 2009 that propelled her into the spotlight. The spouses were married in 2007 in Canada, though their marriage was not legally recognized in the U.S. When Spyer died, Windsor inherited her estate. “But the Internal Revenue Service denied her the unlimited spousal exemption from federal estate taxes available to married heterosexuals, and she had to pay taxes of $363,053,” the New York Times said. So, Windsor sued the United States.

“On a deeply personal level, I felt distressed and anguished that in the eyes of my government, the woman I had loved and cared for and shared my life with was not my legal spouse,” Windsor told Buzzfeed. By 2013, her lawsuit made it to the Supreme Court where the Defense of Marriage Act was struck down as unconstitutional by a 5-4 ruling. United States v. Windsor was a catalyst for the legalization of gay marriage — something that was achieved in 2015 on a federal, nationwide level when the Supreme Court ruled that the 14 Amendment granted all citizens the right same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges.

“Married is a magic word,” Windsor told a rally outside City Hall in New York in 2009, the New York Times reported. “And it is magic throughout the world. It has to do with our dignity as human beings, to be who we are openly.”

Jersey City mayor mercilessly mocks Chris Christie’s beachgate in new campaign video

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (Credit: AP/Seth Wenig)

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie will never live down his ill-timed trip to the beach this summer (and well he shouldn’t). One man making sure of this is Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop, who has immortalized the Christie family’s escapade in a new ad for his re-election campaign.

“They used to say politics in New Jersey is no day at the beach,” Fulop jokes at the opening of the 30-second commercial. “Until suddenly it was.” Lounging in a beach chair just like Christie’s, Fulop gives his constituents a tour of his accomplishments, while savagely mocking his unpopular governor in the process.

In one scene, Fulop appears in his chair outside a school where children are seen racing home for the day. Fulop then touts the three new local schools built during his tenure. He then talks up the popularity of farmers’ markets “in every neighborhood,” as he sits next to a pile of watermelons. Still in his beach chair, Fulop then boasts about the new parks and playgrounds in Jersey City, as a young athlete shoots a soccer ball right at his face.

“Instead of more negative politics, this is a way to show you what we are getting done in Jersey City,” Fulop says, still recumbent. Taste the joy yourself in the clip below:

Due to a budget impasse last July, New Jersey closed all state parks and beaches on the July 4th weekend, but this had no ill effect on Christie’s holiday plans. The governor and his family snuck away to a state-owned retreat at Island Beach State Park, where the former Trump campaign official and presidential candidate was photographed taking in the otherwise uncrowded shore.

Christie, who had a 15 percent approval rating at the time, downplayed the ensuing outrage over his family outing, saying that the state-owned property was not using any resources, and it was his right as governor to enjoy it. His most significant policy move since has been yelling at a Cubs fan during a game in Milwaukee.

Tomgram: Alfred McCoy, how the Pentagon snatched innovation from the jaws of defeat

(Credit: Wikipedia)

The Pentagon’s New Wonder Weapons for World Dominion

Or Buck Rogers in the 21st Century

[This piece has been adapted and expanded from Alfred W. McCoy’s new book, In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power.]

Not quite a century ago, on January 7, 1929, newspaper readers across America were captivated by a brand-new comic strip, “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.” It offered the country its first images of space-age death rays, atomic explosions, and inter-planetary travel.

“I was twenty years old,” World War I veteran Anthony “Buck” Rogers told readers in the very first strip, “surveying the lower levels of an abandoned mine near Pittsburgh … when suddenly … gas knocked me out. But I didn’t die. The peculiar gas … preserved me in suspended animation. Finally, another shifting of strata admitted fresh air and I revived.”

Staggering out of that mine, he finds himself in the 25th century surrounded by flying warriors shooting ray guns at each other. A Mongol spaceship overhead promptly spots him on its “television view plate” and fires its “disintegrator ray” at him. He’s saved from certain death by a flying woman warrior named Wilma who explains to him how this all came to be.

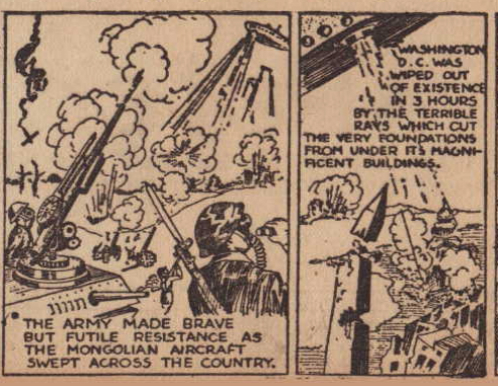

Mongol airships fire disintegrator rays to destroy America.

(Buck Rogers, 2429 A.D., 2-9-1929, Roland N. Anderson Collection)

“Many years ago,” she says, “the Mongol Reds from the Gobi Desert conquered Asia from their great airships held aloft by gravity Repellor Rays. They destroyed Europe, then turned toward peace-loving America.” As their disintegrator beams boiled the oceans, annihilated the U.S. Navy, and demolished Washington, D.C. in just three hours, “government ceased to exist, and mobs, reduced to savagery, fought their way out of the cities to scatter and hide in the country. It was the death of a nation.” While the Mongols rebuilt 15 cities as centers of “super scientific magnificence” under their evil emperor, Americans led “hunted lives in the forests” until their “undying flame of freedom” led them to recapture “lost science” and “once more strike for freedom.”

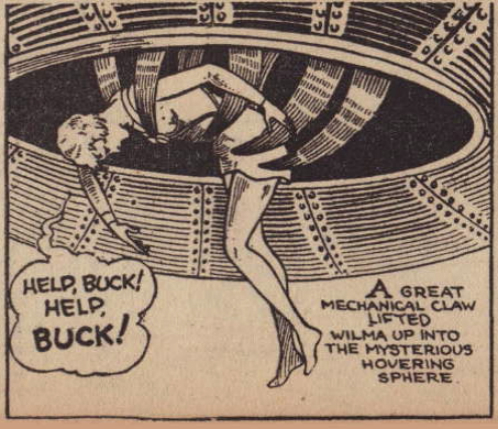

After a year of such cartoons filled with the worst of early-twentieth-century Asian stereotypes, just as Wilma is clinging to the airship of the Mongol Viceroy as it speeds across the Pacific, a mysterious metallic orb appears high in the sky and fires death rays, sending the Mongol ship “hissing into the sea.” With her anti-gravity “inertron” belt, the intrepid Wilma dives safely into the waves only to have a giant metal arm shoot out from the mysterious orb and pull her on board to reveal — “Horrors! What strange beings!” — Martians!

Space Warrior Wilma is pulled from the Pacific into a Martian space orb.

(Buck Rogers, 2430 A.D., 2-27-1930, Roland N. Anderson Collection)

With that strip, “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century” moved from Earth-bound combat against racialized Asians into space wars against monsters from other planets that, over the next 70 years, would take the strip into comic books, radio broadcasts, feature films, television serials, video games, and the country’s collective conscious. It would offer defining visions of space warfare for generations of Americans.

Back in the 21st Century

Now imagine us back in the 21st century. It’s 2030 and an American “triple canopy” of pervasive surveillance systems and armed drones already fills the heavens from the lower stratosphere to the exo-atmosphere. It can deliver its weaponry anywhere on the planet with staggering speed, knock out enemy satellite communications at a moment’s notice, or follow individuals biometrically for great distances. It’s a wonder of the modern age. Along with the country’s advanced cyberwar capacity, it’s also the most sophisticated military information system ever created and an insurance policy for global dominion deep into the twenty-first century.

That is, in fact, the future as the Pentagon imagines it and it’s actually under development, even though most Americans know little or nothing about it. They are still operating in another age, as was Mitt Romney during the 2012 presidential debates when he complained that “our Navy is smaller now than at any time since 1917.”

With words of withering mockery, President Obama shot back: “Well, Governor, we also have fewer horses and bayonets, because the nature of our military’s changed … the question is not a game of Battleship, where we’re counting ships. It’s what are our capabilities.” Obama then offered just a hint of what those capabilities might be: “We need to be thinking about cyber security. We need to be talking about space.”

Indeed, working in secrecy, the Obama administration was presiding over a revolution in defense planning, moving the nation far beyond bayonets and battleships to cyberwarfare and the future full-scale weaponization of space. From stratosphere to exosphere, the Pentagon is now producing an armada of fantastical new aerospace weapons worthy of Buck Rogers.

In 2009, building on advances in digital surveillance under the Bush administration, Obama launched the U.S. Cyber Command. Its headquarters were set up inside the National Security Agency (NSA) at Fort Meade, Maryland, and a cyberwar center staffed by 7,000 Air Force employees was established at Lackland Air Base in Texas. Two years later, the Pentagon moved beyond conventional combat on air, land, or sea to declare cyberspace both an offensive and defensive “operational domain.” In August, despite his wide-ranging attempt to purge the government of anything connected to Barack Obama’s “legacy,” President Trump implemented his predecessor’s long-delayed plan to separate that cyber command from the NSA in a bid to “strengthen our cyberspace operations.”

And what is all this technology being prepared for? In study after study, the intelligence community, the Pentagon, and related think tanks have been unanimous in identifying the main threat to future U.S. global hegemony as a rival power with an expanding economy, a strengthening military, and global ambitions: China, the home of those denizens of the Gobi Desert who would, in that old “Buck Rogers” fable, destroy Washington four centuries from now. Given that America’s economic preeminence is fading fast, breakthroughs in “information warfare” might indeed prove Washington’s best bet for extending its global hegemony further into this century — but don’t count on it, given the history of techno-weaponry in past wars.

Techno-Triumph in Vietnam

Ever since the Pentagon with its 17 miles of corridors was completed in 1943, that massive bureaucratic maze has presided over a creative fusion of science and industry that President Dwight Eisenhower would dub “the military-industrial complex” in his farewell address to the nation in 1961. “We can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense,” he told the American people. “We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions” sustained by a “technological revolution” that is “complex and costly.” As part of his own contribution to that complex, Eisenhower had overseen the creation of both the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, and a “high-risk, high-gain” research unit called the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA, that later added the word “Defense” to its name and became DARPA.

For 70 years, this close alliance between the Pentagon and major defense contractors has produced an unbroken succession of “wonder weapons” that at least theoretically gave it a critical edge in all major military domains. Even when defeated or fought to a draw, as in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, the Pentagon’s research matrix has demonstrated a recurring resilience that could turn disaster into further technological advance.

The Vietnam War, for example, was a thoroughgoing tactical failure, yet it would also prove a technological triumph for the military-industrial complex. Although most Americans remember only the Army’s soul-destroying ground combat in the villages of South Vietnam, the Air Force fought the biggest air war in military history there and, while it too failed dismally and destructively, it turned out to be a crucial testing ground for a revolution in robotic weaponry.

To stop truck convoys that the North Vietnamese were sending through southern Laos into South Vietnam, the Pentagon’s techno-wizards combined a network of sensors, computers, and aircraft in a coordinated electronic bombing campaign that, from 1968 to 1973, dropped more than a million tons of munitions — equal to the total tonnage for the whole Korean War — in that limited area. At a cost of $800 million a year, Operation Igloo White laced that narrow mountain corridor with 20,000 acoustic, seismic, and thermal sensors that sent signals to four EC-121 communications aircraft circling ceaselessly overhead.

At a U.S. air base just across the Mekong River in Thailand, Task Force Alpha deployed two powerful IBM 360/65 mainframe computers, equipped with history’s first visual display monitors, to translate all those sensor signals into “an illuminated line of light” and so launch jet fighters over the Ho Chi Minh Trail where computers discharged laser-guided bombs automatically. Bristling with antennae and filled with the latest computers, its massive concrete bunker seemed, at the time, a futuristic marvel to a visiting Pentagon official who spoke rapturously about “being swept up in the beauty and majesty of the Task Force Alpha temple.”

However, after more than 100,000 North Vietnamese troops with tanks, trucks, and artillery somehow moved through that sensor field undetected for a massive offensive in 1972, the Air Force had to admit that its $6 billion “electronic battlefield” was an unqualified failure. Yet that same bombing campaign would prove to be the first crude step toward a future electronic battlefield for unmanned robotic warfare.

In the pressure cooker of history’s largest air war, the Air Force also transformed an old weapon, the “Firebee” target drone, into a new technology that would rise to significance three decades later. By 1972, the Air Force could send an “SC/TV” drone, equipped with a camera in its nose, up to 2,400 miles across communist China or North Vietnam while controlling it via a low-resolution television image. The Air Force also made aviation history by test firing the first missile from one of those drones.

The air war in Vietnam was also an impetus for the development of the Pentagon’s global telecommunications satellite system, another important first. After the Initial Defense Satellite Communications System launched seven orbital satellites in 1966, ground terminals in Vietnam started transmitting high-resolution aerial surveillance photos to Washington — something NASA called a “revolutionary development.” Those images proved so useful that the Pentagon quickly launched an additional 21 satellites and soon had the first system that could communicate from anywhere on the globe. Today, according to an Air Force website, the third phase of that system provides secure command, control, and communications for “the Army’s ground mobile forces, the Air Force’s airborne terminals, Navy ships at sea, the White House Communications Agency, the State Department, and special users” like the CIA and NSA.

At great cost, the Vietnam War marked a watershed in Washington’s global information architecture. Turning defeat into innovation, the Air Force had developed the key components — satellite communications, remote sensing, computer-triggered bombing, and unmanned aircraft — that would merge 40 years later into a new system of robotic warfare.

The War on Terror

Facing another set of defeats in Afghanistan and Iraq, the twenty-first-century Pentagon again accelerated the development of new military technologies. After six years of failing counterinsurgency campaigns in both countries, the Pentagon discovered the power of biometric identification and electronic surveillance to help pacify sprawling urban areas. And when President Obama later conducted his troop “surge” in Afghanistan, that country became a frontier for testing and perfecting drone warfare.

Launched as an experimental aircraft in 1994, the Predator drone was deployed in the Balkans that very year for photo-reconnaissance. In 2000, it was adapted for real-time surveillance under the CIA’s Operation Afghan Eyes. It would be armed with the tank-killing Hellfire missile for the agency’s first lethal strike in Kandahar, Afghanistan, in October 2001. Seven years later, the Air Force introduced the larger MQ-9 “Reaper” drone with a flying range of 1,150 miles when fully loaded with Hellfire missiles and GBU-30 bombs, allowing it to strike targets almost anywhere in Europe, Africa, or Asia. To fulfill its expanding mission as Washington’s global assassin, the Air Force plans to have 346 Reapers in service by 2021, including 80 for the CIA.

Between 2004 and 2010, total flying time for all unmanned aerial vehicles rose sharply from just 71 hours to 250,000 hours. By 2011, there were already 7,000 drones in a growing U.S. armada of unmanned aircraft. So central had they become to its military power that the Pentagon was planning to spend $40 billion to expand their numbers by 35% over the following decade. To service all this growth, the Air Force was training 350 drone pilots, more than all its bomber and fighter pilots combined.

Miniature or monstrous, hand-held or runway-launched, drones were becoming so commonplace and so critical for so many military missions that they emerged from the war on terror as one of America’s wonder weapons for preserving its global power. Yet the striking innovations in drone warfare are, in the long run, likely to be overshadowed by stunning aerospace advances in the stratosphere and exosphere.

The Pentagon’s Triple Canopy

As in Vietnam, despite bitter reverses on the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan, Washington’s recent wars have been catalysts for the fusion of aerospace, cyberspace, and artificial intelligence into a new military regime of robotic warfare.

To effect this technological transformation, starting in 2009 the Pentagon planned to spend $55 billion annually to develop robotics for a data-dense interface of space, cyberspace, and terrestrial battle space. Through an annual allocation for new technologies reaching $18 billion in 2016, the Pentagon had, according to the New York Times, “put artificial intelligence at the center of its strategy to maintain the United States’ position as the world’s dominant military power,” exemplified by future drones that will be capable of identifying and eliminating enemy targets without recourse to human overseers. By 2025, the United States will likely deploy advanced aerospace and cyberwarfare to envelop the planet in a robotic matrix theoretically capable of blinding entire armies or atomizing an individual insurgent.

During 15 years of nearly limitless military budgets for the war on terror, DARPA has spent billions of dollars trying to develop new weapons systems worthy of “Buck Rogers” that usually die on the drawing board or end in spectacular crashes. Through this astronomically costly process of trial and error, Pentagon planners seem to have come to the slow realization that established systems, particularly drones and satellites, could in combination create an effective aerospace architecture.

Within a decade, the Pentagon apparently hopes to patrol the entire planet ceaselessly via a triple-canopy aerospace shield that would reach from sky to space and be secured by an armada of drones with lethal missiles and Argus-eyed sensors, monitored through an electronic matrix and controlled by robotic systems. It’s even possible to take you on a tour of the super-secret realm where future space wars will be fought, if the Pentagon’s dreams become reality, by exploring both DARPA websites and those of its various defense contractors.

Drones in the Lower Stratosphere

At the bottom tier of this emerging aerospace shield in the lower stratosphere (about 30,000 to 60,000 feet high), the Pentagon is working with defense contractors to develop high-altitude drones that will replace manned aircraft. To supersede the manned U-2 surveillance aircraft, for instance, the Pentagon has been preparing a projected armada of 99 Global Hawk drones at a mind-boggling cost of $223 million each, seven times the price of the current Reaper model. Its extended 116-foot wingspan (bigger than that of a Boeing 737) is geared to operating at 60,000 feet. Each Global Hawk is equipped with high-resolution cameras, advanced electronic sensors, and efficient engines for a continuous 32-hour flight, which means that it can potentially survey up to 40,000 square miles of the planet’s surface daily. With its enormous bandwidth needed to bounce a torrent of audio-visual data between satellites and ground stations, however, the Global Hawk, like other long-distance drones in America’s armada, may prove vulnerable to a hostile hack attack in some future conflict.

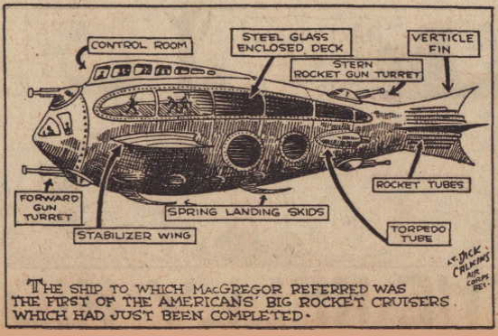

In 1929, Buck Rogers imagines America’s future spacecraft for space wars.

(Buck Rogers, 2429 A.D., 8-26-1929, Roland N. Anderson Collection.)

The sophistication, and limitations, of this developing aerospace technology were exposed in December 2011 when an advanced RQ-170 Sentinel drone suddenly landed in Iran, whose officials then released photos of its dart-shaped, 65-foot wingspan meant for flights up to 50,000 feet. Under a highly classified “black” contract, Lockheed Martin had built 20 of these espionage drones at a cost of about $200 million with radar-evading stealth and advanced optics that were meant to provide “surveillance support to forward-deployed combat forces.”

So what was this super-secret drone doing in hostile Iran? By simply jamming its GPS navigation system, whose signals are notoriously susceptible to hacking, Iranian engineers took control of the drone and landed it at a local base of theirs with the same elevation as its home field in neighboring Afghanistan. Although Washington first denied the capture, the event sent shock waves down the Pentagon’s endless corridors.

In the aftermath of this debacle, the Defense Department worked with one of its top contractors, Northrop Grumman, to accelerate development of its super-stealth RQ-180 drone with an enormous 130-foot wingspan, an extended range of 1,200 miles, and 24 hours of flying time. Its record cost, $300 million a plane, could be thought of as inaugurating a new era of lavishly expensive war-fighting drones.

Simultaneously, the Navy’s dart-shaped X-47B surveillance and strike drone has proven capable both of in-flight refueling and of carrying up to 4,000 pounds of bombs or missiles. Three years after it passed its most crucial test by a joy-stick landing on the deck of an aircraft carrier, the USS George H.W. Bush in July 2013, the Navy announced that this experimental drone would enter service sometime after 2020 as the “MQ-25 Stingray” aircraft.

Dominating the Upper Stratosphere

To dominate the higher altitudes of the upper stratosphere (about 70,000 to 160,000 feet), the Pentagon has pushed its contractors to the technological edge, spending billions of dollars on experimentation with fanciful, futuristic aircraft.

For more than 20 years, DARPA pursued the dream of a globe-girding armada of solar-powered drones that could fly ceaselessly at 90,000 feet and would serve as the equivalent of low-flying satellites, that is, as platforms for surveillance intercepts or signals transmission. With an arching 250-foot wingspan covered with ultra-light solar panels, the “Helios” drone achieved a world-record altitude of 98,000 feet in 2001 before breaking up in a spectacular crash two years later. Nonetheless, DARPA launched the ambitious “Vulture” project in 2008 to build solar-powered aircraft with hugewingspans of 300 to 500 feet capable of ceaseless flight at 90,000 feet for five years at a time. After DARPA abandoned the project as impractical in 2012, Google and Facebook took over the technology with the goal of building future platforms for their customers’ Internet connections.

Since 2003, both DARPA and the Air Force have struggled to shatter the barrier for suborbital speeds by developing the dart-shaped Falcon Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle. Flying at an altitude of 100,000 feet, it was expected to “deliver 12,000 pounds of payload at a distance of 9,000 nautical miles from the continental United States in less than two hours.” Although the first test launches in 2010 and 2011 crashed in mid-flight, they did briefly reach an amazing 13,000 miles per hour, 22 times the speed of sound.

As often happens, failure produced progress. In the wake of the Falcon’s crashes, DARPA has applied its hypersonics to develop a missile capable of penetrating China’s air-defenses at an altitude of 70,000 feet and a speed of Mach 5 (about 3,300 miles per hour).

Simultaneously, Lockheed’s secret “Skunk Works” experimental unit is using the hypersonic technology to develop the SR-72 unmanned surveillance aircraft as a successor to its SR-71 Blackbird, the world’s fastest manned aircraft. When operational by 2030, the SR-72 is supposed to fly at about 4,500 mph, double the speed of its manned predecessor, with an extreme stealth fuselage making it undetectable as it crosses any continent in an hour at 80,000 feet scooping up electronic intelligence.

Space Wars in the Exosphere

In the exosphere, 200 miles above Earth, the age of space warfare dawned in April 2010 when the Defense Department launched the robotic X-37B spacecraft, just 29 feet long, into orbit for a seven-month mission. By removing pilots and their costly life-support systems, the Air Force’s secretive Rapid Capabilities Office had created a miniaturized, militarized space drone with thrusters to elude missile attacks and a cargo bay for possible air-to-air missiles. By the time the second X-37B prototype landed in June 2012, its flawless 15-month flight had established the viability of “robotically controlled reusable spacecraft.”

In the exosphere where these space drones will someday roam, orbital satellites will be the prime targets in any future world war. The vulnerability of U.S. satellite systems became obvious in 2007 when China used a ground-to-air missile to shoot down one of its own satellites in orbit 500 miles above the Earth. A year later, the Pentagon accomplished the same feat, firing an SM-3 missile from a Navy cruiser to score a direct hit on a U.S. satellite 150 miles high.

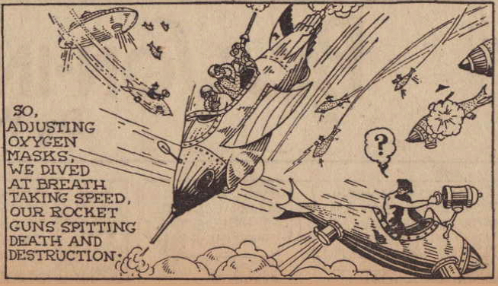

In a 1929 comic strip, Buck Rogers fights space wars in the 25th Century.

(Buck Rogers, 2429 A.D., 5-8-1929, Roland N. Anderson Collection)

Unsuccessful in developing an advanced F-6 satellite, despite spending over $200 million in an attempt to split the module into more resilient microwave-linked components, the Pentagon has opted instead to upgrade its more conventional single-module satellites, such as the Navy’s five interconnected Mobile User Objective Systems (MUOS) satellites. These were launched between 2013 and 2016 into geostationary orbits for communications with aircraft, ships, and motorized infantry.

Reflecting its role as a player in the preparation for future and futuristic wars, the Joint Functional Component Command for Space, established in 2006, operates the Space Surveillance Network. To prevent a high-altitude attack on America, this worldwide system of radar and telescopes in 29 remote locations like Ascension Island and Kwajalein Atoll makes about 400,000 observations daily, monitoring every object in the skies.

The Future of Wonder Weapons

By the mid-2020s, if the military’s dreams are realized, the Pentagon’s triple-canopy shield should be able to atomize a single “terrorist” with a missile strike or, with equal ease, blind an entire army by knocking out all of its ground communications, avionics, and naval navigation. It’s a system that, were it to work as imagined, just might allow the United States a diplomatic veto of global lethality, an equalizer for any further loss of international influence.

But as in Vietnam, where aerospace wonders could not prevent a searing defeat, history offers some harsh lessons when it comes to technology trumping insurgencies, no less the fusion of forces (diplomatic, economic, and military) whose sum is geopolitical power. After all, the Third Reich failed to win World War II even though it had amazingly advanced “wonder weapons,” including the devastating V-2 missile, the unstoppable Me-262 jet fighter, and the ship-killing Hs-293 guided missile.

Washington’s dogged reliance on and faith in military technology to maintain its hegemony will certainly guarantee endless combat operations with uncertain outcomes in the forever war against terrorists along the ragged edge of Asia and Africa and incessant future low-level aggression in space and cyberspace. Someday, it may even lead to armed conflict with rivals China and Russia.

Whether the Pentagon’s robotic weapon systems will offer the U.S. an extended lease on global hegemony or prove a fantasy plucked from the frames of a “Buck Rogers” comic book, only the future can tell. Whether, in that moment to come, America will play the role of the indomitable Buck Rogers or the Martians he eventually defeated is another question worth asking. One thing is likely, however: that future is coming far more quickly and possibly far more painfully than any of us might imagine.

Alfred W. McCoy, a TomDispatch regular, is the Harrington professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of the now-classic book The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, which probed the conjuncture of illicit narcotics and covert operations over 50 years, and the just-published In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power (Dispatch Books) from which this piece is adapted.

Why giving cash, not clothing, is usually best after disasters

(Credit: AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

Between the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other government entities, nonprofits large and small, and contributions from concerned individuals, a massive Hurricane Harvey relief effort is taking shape.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh’s “Help for Houston” drive and countless other community collections illustrate the American impulse to help people whose lives have been upended by catastrophic floods. But like his campaign, these well-intentioned bids to ship goods to distant locales in Texas are perpetuating a common myth of post-disaster charitable giving.

As a researcher with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, an interdisciplinary center at Harvard University dedicated to relieving human suffering in wartime and disasters by analyzing and improving the way professionals and communities respond to emergencies, I’ve seen the evidence on dozens of disasters, from Superstorm Sandy to the South Asian Tsunami. It all points to a clear conclusion: In-kind donations of items such as food, clothing, toiletries and diapers are often the last thing that is needed in disaster-affected areas.

Delivering things that people need on the ground simply doesn’t help disaster-struck communities as much as giving them — and relief organizations — money to buy what they need. What’s more, truckloads of blue jeans and cases of Lunchables can actually interfere with official relief efforts.

If you want to do the greatest good, send money.

Update: truck #8 is fully packed and on its way to Houston. A big thank you to everyone working hard to get these supplies to Texas. pic.twitter.com/3Rt2LrnvYl

— Mayor Marty Walsh (@marty_walsh) September 2, 2017

What’s wrong with in-kind donations

As humanitarian workers and volunteers have witnessed after disasters like Haiti’s 2010 earthquake and Typhoon Haiyan, disaster relief efforts repeatedly provide lessons in good intentions gone wrong.

At best, in-kind donations augment official efforts and provide the locals with some additional comfort, especially when those donations come from nearby. When various levels of government failed to meet the needs of Hurricane Katrina victims, for example, community, faith-based and private sector organizations stepped in to fill many of the gaps.

How can in-kind donations cause more harm than good? While ostensibly free, donated goods raise the cost of the response cycle: from collecting, sorting, packaging and shipping bulky items across long distances to, upon arrival, reception, sorting, warehousing and distribution.

Delivering this aid is extremely tough in disaster areas since transportation infrastructure, such as airports, seaports, roads and bridges, are likely to be, if not damaged or incapacitated by the initial disaster, already clogged by the surge of incoming first responders, relief shipments and equipment.

Dumping grounds

At worst, disaster zones become dumping grounds for inappropriate goods that delay actual relief efforts and harm local economies.

After the 2004 South Asian tsunami, shipping containers full of ill-suited items such as used high-heeled shoes, ski gear and expired medications poured into the affected countries. This junk clogged ports and roads, polluting already ravaged areas and diverting personnel, trucks and storage facilities from actual relief efforts.

After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, many untrained and uninvited American volunteers bringing unnecessary goods ended up needing assistance themselves.

In-kind donations often not only fail to help those in actual need but cause congestion, tie up resources and further hurt local economies when dumped on the market, as research from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies determined.

From Joplin to Japan

Research confirms that a significant portion of aid dispatched to disaster areas is “non-priority,” inappropriate or useless.

One study led by José Holguín-Veras, a Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute expert on humanitarian logistics, found that 50 percent to 70 percent of the goods that arrive during these emergencies should never have been sent and interfere with recovery efforts. After the 2011 Joplin, Missouri tornado and the Tōhoku, Japan earthquake, for example, excessive donations of clothing and blankets tied up relief personnel. The situation was similar after Hurricane Katrina.

Relief workers consider these well-meaning but inconvenient donations as a “second tier disaster” due to the disruption they cause.

And yet Americans are organizing this kind of donation drive in places like Sea Bright, New Jersey, Pleasant View, Tennessee, Escondido, California, Florida’s Treasure Coast, Chicago and Madison, Wisconsin.

What else can you do?

Instead of shipping your hand-me-downs, donate money to trusted and established organizations with extensive experience and expertise — and local ties.

Give to groups that make it clear where the money will go. Choose relief efforts that will procure supplies near the disaster area, which will help the local economy recover. Many media outlets, including The New York Times and NPR, have published helpful guides that list legitimate and worthy options. You can also consult Charity Navigator, a nonprofit that evaluates charities’ financial performance.

Many humanitarian aid organizations themselves have increasingly adopted cash-based approaches in recent years, though money remains a small share of overall humanitarian aid worldwide.

Evaluations of the effectiveness of such programs vary and are context-dependent. Nonetheless, emerging evidence suggests that disbursing cash is often the best way to help people in disaster zones get the food and shelter they need. What’s more, the World Food Program and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees say that people affected by disasters tend to prefer cash over in-kind aid due to the dignity, control and flexibility it gives them.

Exceptions

There are a few notable exceptions to this advice on avoiding in-kind donations.

If you live in or near the affected area, it is helpful to consider dropping the specific items victims are requesting at local food banks, shelters and other community organizations. Just make sure that the items won’t perish by the time they can be distributed. Examples of some locally requested items in Houston include diapers, cleaning and building supplies, and new bedding.

Charity is a virtue. Particularly when disaster strikes, the urge to help is admirable. Yet this impulse should be channeled to do the greatest good. So please, if you would like to help from afar, let the professionals procure goods and services. Instead, donate money and listen to what people on the ground say they need.

And don’t stop giving after the disaster stops making headlines. A full recovery will take time — and support long after the emergency responders and camera crews have moved on.

Julia Brooks, Researcher in international law and humanitarian response, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI), Harvard University

5 absurd attempts to equate right-wing terrorists with left-wing groups

'Antifa' protesters link arms as they demonstrate at a rally (Credit: Getty/Natalie Behring)

“Sure, the cancer was aggressive. But the chemotherapy was also very aggressive. There was aggression on both sides.” — Elan Gale

There’s a long history of right-wingers and centrists falsely equating racist violence with freedom movements. Andray Domise notes that “after the election of 1832, New Hampshire governor and Jacksonian Democrat Isaac Hill labeled abolitionists as ‘troublemakers’ who were driving a wedge between the North and the South, and that their ‘pathetic appeals’ were sapping the foundation of democracy.”

Recently, Twitter helped resurface a newspaper article from 1956 in which Gov. Earl Long of Louisiana disingenuously labeled both violent segregationists and Martin Luther King, Jr. “extremists.”

Since the events of Charlottesville, there’s been a concerted effort by the right, modeled by Donald Trump, to make political violence a problem of the left, as if Heather Heyer had not been killed by a white nationalist linked to the oldest and most thriving terror organization in this country.

A complicit media and moderate Democrats have followed suit, but the whole idea is ludicrous. Here are five examples of false equivalencies between far-right terrorists and antifa.

1. Right-wing extremists commit nearly all political violence in America

A recent study from the Anti-Defamation League finds nearly all political violence in the United States over the last decade has been carried out by right-wing terrorists. Between 2007 and 2016, there were at least 372 politically motivated murders, 74 percent of which were committed by right-wing extremists. Islamic extremists committed 24 percent of those murders, while left-wing militants were responsible for 2 percent. Every murder is a tragedy, but as the numbers show, it’s ridiculous to pretend that left-wing violence and right-wing violence deserve equal concern. Going back to a 2015 law enforcement study, we’ve known that right-wing terrorists pose a far greater threat to this country than any other political group.

“We find that the right groups and the jihadi groups are more violent than the left,” Gary LaFree, head of the University of Maryland National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism and co-author of a recent study on political violence across the spectrum, told the New York Times.

The far right — an umbrella term that includes white nationalists, neo-fascists, the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, alt-right adherents, anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant groups, anti-government militias, and anti-abortion fanatics like clinic bombers — are the heirs apparent of violent right-wing terror groups dating to the earliest eras of American history. It’s therefore not terribly surprising that based on every statistical measure, as Mother Jones notes, they have “held a near-monopoly on political violence since the 1980s.”

That’s echoed by Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project leader Heidi Beirich, who told the Nation, “if you go back to the 1960s, you see all kinds of left-wing terrorism, but since then it’s been exceedingly rare.” Right-wing terror has proliferated since that era, “going back to groups like the Order, which assassinated [liberal talk-radio host] Alan Berg [in 1984] right through to today.”

2. Violence is central to far-right ideology

What do conservatives want to conserve? Mostly, “traditional America,” the version of the country they think is so great. Their vision of the U.S. is homogeneously white and Christian, free of immigrants who don’t speak English and LGBT people forming non-heterosexual unions. On a scale that goes from Proud Boys to neo-Nazis, from Western chauvinists to hardline racists, there’s an underlying philosophy of rejection of a human other. As sociologist and criminologist Stanislav Vysotsky has written, “When even the most moderate position the alt-right or fascist movement can take is racial separation or nationalism through forcible repatriation and strict border control, including forced deportations and racialized exclusions, that movement is inherently violent.”

Matthew Rozsa, writing at Salon, notes:

Indeed, far-right violence is embedded in the very iconography embraced by that movement. As historian David Blight has pointed out, Civil War symbols like the Confederate memorials being taken down in Charlottesville (which was what prompted members of the far right to assemble there) were created in large part to reinforce a code of white supremacy throughout the United States. The event such memorials commemorated, it must be remembered, was also one rooted in violence — a collection of states using anti-government rhetoric to protect a white supremacist society through violent rebellion against the federal government.

From the Black Panthers to contemporary antifa, far-left groups that have embraced violence have done so with a sense of finality and self-protection, recognizing that violence is the only language their opposition understands.

“Antifascists are focused on a singular goal as described by their movement name: opposing fascism,” Vysotsky continues. “It would be a mischaracterization to claim that antifa oppose nonviolence. Instead, it is more accurate to say that antifa often justifiably view nonviolence as ineffective against a movement that is violent at its core, and participants who seem to lack any semblance of a conscience. This is the essence of antifascist use of violence.”

3. Right-wing terrorists attack people, while left-wing groups mostly target property

The University of Maryland study co-authored by LaFree found “far-right individuals were more likely to commit violence against people, while those on the far left were more likely to commit property damage.”

SPLC’s Beirich told the Nation “eco- and animal-rights extremists caused extensive property damage in the 1990s, but didn’t target people.”

There’s a debate to be had about whether property damage is an effective statement of political protest or tool of social change. There is not a valid discussion to be had on whether hurting property is the same as hurting people.

4. Antifa is not backed by mainstream progressives, while Republicans have embraced the far right

There are no highly visible progressives, prominent liberals or Democratic stars who have risked their own public image to defend antifa. In fact, they’re far more likely to parrot the bothsideism of the right, ridiculously and illogically equating fascists and anti-fascists.

Republicans, on the other hand, have nearly fallen over themselves to let right-wing extremists know they approve of their ideas and welcome them to the party. Lots of Republican lawmakers, including Rand Paul, applauded Cliven Bundy’s armed standoff with the federal government. House Minority Leader John Boehner bashed a 2009 Department of Homeland Security report on rising right-wing threats including hate groups. In the weeks after Dylann Roof’s killing rampage, there were GOP voices still proudly defending the Confederate flag.

The current administration has been transparently supportive of the alt-right. Steve Bannon boasted about turning Breitbart into the “platform of the alt-right.” The White House has given press passes to alt-right trolls Mike Cernovichand Jack Posobiec. And Donald Trump has been vocal in expressing his sympathy for neo-Nazis since Charlottesville. As the Daily Beast’s Dean Obeidallah succinctly notes, “antifa is not part of the Democratic Party, while white supremacists are part of the GOP.”

5. Community service is part of the mission of antifa.

The Panthers served free breakfast to schoolchildren, along with 60 other community programs including health care clinics and free legal aid. Antifa groups like the Redneck Revolution run “food programs, community gardens, clothing programs, and needle exchanges in addition to their armed self-defense programs.”

Black Lives Matter and antifa groups were both on the ground during Hurricane Harvey handing out food and supplies to survivors. At the Boston anti-Nazi rally, members of BLM escorted white nationalists through the crowd to ensure their safety.

It would be absurd to pretend members of antifa don’t engage in violence. But when was the last time you heard about the Klan handing out food to poor people or the alt-right setting up education programs for at-risk kids? You haven’t, ever, and if you decide to wait for such an event to take place, you should probably get your affairs in order first.

September 11, 2017

White Christians are now a minority — but they’re getting more isolated and less tolerant

(Credit: Getty/dbvirago)

Last week, the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) put out a new report on religion in America that measured a truly remarkable shift: For the first time, almost certainly in the country’s history, people who identify as white Christians are a minority of Americans. Four out of every five Americans were self-described white Christians in 1976, but now that group only constitutes 43 percent of the U.S. population.

There are a lot of reasons for this shift, study author Robert P. Jones, who heads PRRI and is the author of “The End of White Christian America,” explained to Salon in an interview. To a large extent, Jones said, it’s the trend of “young, white people leaving Christian churches that is driving up the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans.”

This reflects, he added, “a culture clash between particularly conservative white churches and denominations and younger Americans” over issues like science, particularly climate change and evolution, and especially the rights of LGBT people.

It’s a battle that goes a long way towards explaining the “Nashville statement,” released last month by the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. While the statement includes some language criticizing straight people who fail to practice “chastity outside of marriage,” by and large it is meant as an attack on LGBT Americans, suggesting, for instance, that no good Christians can “approve of homosexual immorality or transgenderism.”

“The younger generation, Americans under the age of 30 — more than eight in 10 of them support same-sex marriage,” Jones said, adding that the issue has become “a litmus test issue for many millennials in the country.”

“It’s not just that conservative white Christians have lost this argument with a broader liberal culture,” he noted. “It’s that they’ve lost it with their own kids and grandchildren.”

Statistics seem to bear this out. A slim majority of young white evangelicals now support same-sex marriage, while older generations of white evangelicals overwhelmingly oppose it. That difference doesn’t even take into account the huge numbers of young people who were raised in evangelical denominations and then left their churches, often because they disapprove of religious homophobia.

These trends lead Jones to believe that the Nashville statement was not really aimed at the larger American culture. Rather, it was an attempt by older, more conservative evangelicals to “reassert a view that has certainly lost its footing” with their own children and grandchildren. This is why, he speculated, the language is less “fire and brimstone” in nature than similar documents in the past.

A recent Washington Post op-ed by Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, also suggests that the Nashville statement is an effort to sell the younger generation on accepting homophobia by soft-pedaling the hate.

“In releasing the Nashville Statement, we in fact are acting out of love and concern for people who are increasingly confused about what God has clarified in Holy Scripture,” Mohler wrote. (“Confused” is conservative Christian-speak for gay, bisexual or transgender — identities that the Nashville statement directly denies exist.)

Mohler went on to insist that the document was simply an effort to clarify and build on a view that marriage is “a covenantal, sexual, procreative, lifelong union of one man and one woman” and that “[c]hastity outside of marriage and fidelity within marriage are affirmed.”

This “love the sinner, hate the sin” spin was a hard sell before, and in the age of Donald Trump, it’s downright laughable. Not only did white evangelicals vote for Trump, but they voted for him in even greater numbers than they had for any other Republican before him — giving Trump even more support than they gave George W. Bush, who is one of their own. The more churchy the white evangelical, the more likely he or she is to support Trump. Many of the signatories of the Nashville statement (though not Mohler) also publicly lent their support to Trump. Signatory James Dobson even justified his choice by saying that Trump “appears to be tender to things of the Spirit,” which can only be described as a ludicrous claim, whether one is religious or not.

Trump committed adultery during his first two marriages and during his current marriage, has bragged on tape about apparently assaulting women. When asked about forgiveness during a Christian-oriented campaign event designed to make him look like a believer, Trump made clear that he had never asked God for forgiveness for these or any other sins and seemed confused about why he would have needed to.

The white evangelical support for Trump, coupled with the continued denunciation of LGBT people, makes it clear this is not and never was about morality, sexual or otherwise. Instead, “morality” is a fig leaf for the true agenda of the Christian right, which is asserting a strict social hierarchy based on gender.

The same-sex marriage question is a stand-in issue, Jones argued, for “a whole worldview” that is “a kind of patriarchal view of the family, with the father head of the household and the mother staying home.”

“I think that’s why this fight is as visceral as it is,” he added.

Trump may be an unrepentant sinner, but he is a supporter of this patriarchal worldview, where straight men are in charge, women are quiet and submissive and people who fall outside these old-school heterosexual norms are marginalized. Voting for him was an obvious attempt by white evangelicals to impose this worldview on others, including (and perhaps especially) their own children, who are starting to ask hard questions about a moral order based on hierarchy and rigid gender roles instead of one built on empathy and kindness.

Rotten Tomatoes must die!

King Arthur: Legend of the Sword; Baywatch; Dunkirk (Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures/Paramount Pictures)

Here’s the plot: Picture “Rocky” meets “The Social Network.” An aging Hollywood comes up against a young, scrappy website. The site may be small (staff: 36), but it’s figured out how to unite all of Hollywood’s biggest enemies (critics) into one Voltron-like force. Can the site — let’s call it Rotten Tomatoes — do what generations of difficult actors and striking writers couldn’t and bring down Hollywood? Or, will our beloved Hollywood prevail? But wait! There’s a twist: Rotten Tomatoes is the child of a group (Fandango) that swore allegiance to Hollywood. Duh duh duh duhhh.

Hollywood studio executives are accustomed to out-there narratives. But the one they’ve concocted to explain their business’s recent sputtering sounds incredible even by their standards — and, lest we not forget, Sony released a coming of age tale about an emoji burdened by multiple emotions this summer.

Last week, several high-profile Hollywood personnel were quoted in The New York Times as saying Rotten Tomatoes, a movie review aggregator, is killing the movie business. One, Brett Ratner (Director of “Rush Hour,” producer of “The Revenant”) went as far as to call the site “the destruction of our business.” Another anonymous exec “declared flatly that his mission was to destroy the review-aggregation site.”Since then, the aggregated have responded: Bologna!

The wide dismissal of Hollywood’s working theory for its recent woes is generally right. Hollywood’s issues have more to do with competition than criticism. The cost to attend a movie has risen astronomically in recent years, while the alternatives have improved in stride. A 2014 poll found that Americans prefer to watch movies at home rather than in the theater. And Americans are going to the theater less often. To get audiences into theaters requires more incentive — not just a good review (or the absence of a bad one) but buzz, the sensation of attending an event.

Rotten Tomatoes was founded in 1998 but has only become pervasive in recent years. Annual ticket sales, meanwhile, have been declining gradually but not consistently since about 2002. The correlation between a decline in moviegoing and the growth of Rotten Tomatoes is hard to spot; causation is even harder to manufacture.

The declining fortunes of the movie industry are not the fault of Rotten Tomatoes. However, that doesn’t mean studio executives and producers are wrong to blame a given big budget film bombing on the review aggregator. At a micro level, Rotten Tomatoes may be having a bigger impact than we think.

There is a chapter in Derek Thompson’s book, “Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction,” published in February, about how things go viral in the age of the internet. Basically, they don’t. Rather than spreading from individual to individual, Thompson, working from research done by Yahoo, argues that “Popularity on the Internet is ‘driven by the size of the largest broadcast.’” Things that spread on the internet are generally shared by one large host source (a celebrity’s Twitter account, a big media outlet, etc.) to many smaller sources with diminishing and discreet (in-person) shares from the infected pool. “Digital blockbusters are not about a million one-to-one moments as much as they are about a few one-to-one-million moments,” Thompson writes.

What’s more, a veneer of quality has been shown to have a large impact on perception of quality. Thompson cites a separate study from Columbia University researchers in which subjects were presented with 48 songs for download on various websites and were instructed to download their favorites. On some sites, the songs were ranked by their popularity and on others they were not ranked. The songs that were most downloaded were different on the different sites. On the sites where the songs were ranked, people tended to download the most popular songs. And when the researchers inverted the rankings on other sites, songs that were formerly unpopular became popular.

Rotten Tomatoes is a large broadcaster, attracting approximately 14 million unique visitors a month. But the 14 million monthly visitors to the site is peanuts compared to the number of people who might search for a given film on Google or Fandango (which owns Rotten Tomatoes). When you search for a movie on Google or Fandango, the sites provide the film’s Tomatometer score. Rotten Tomatoes can conceivably shape the narrative around a movie.

It’s notable that the ten highest grossing movies of the year all have fresh Tomatometers (scores greater than 59%). The recent success of “The Emoji Movie” in the face of an abysmal 8% Tomatometer score has been cited as an exception disproving the rule that Rotten Tomatoes can sink movies. However, it may be the exception proving the rule. Sony embargoed reviews on “The Emoji Movie” until the film’s wide release, which, as the Times notes, “left the Tomatometer blank until after many advance tickets had been sold and families had made weekend plans.”

Meanwhile, some of the year’s biggest bombs, like “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword” and “Baywatch,” were pilloried by critics, with abysmal Tomatometer scores to boot (27% for “King Arthur,” 18% for “Baywatch”). But interestingly, the audiences that did see those films didn’t hate them. Rotten Tomatoes also calculates an Audience Score, based on users’ rankings. The Audience Scores for “King Arthur” and “Baywatch” were nearly as fresh (71% for “King Arthur,” 60% for “Baywatch”) as the Audience Score for “Dunkirk” (82%).

There’s a temptation on the part of critics and bloggers to respond to Hollywood executives’ lamentations about poor Tomatometer scores with a snide, “Well, how about making better movies?” But Hollywood cynicism about moviegoing is based in reality. Most moviegoers don’t watch films the same way or for the same reasons as critics. They like sequels, they like franchises, they like bigness, they like fun and they don’t like to be challenged. Of the top ten highest grossing films of the year, only two (“Dunkirk” and “Get Out”) are original concepts, and each of those films was bolstered by the media portraying them as must-see events.

“King Arthur” and “Baywatch,” meanwhile, were liked well enough by audiences that it’s worth asking why they flopped. Did they suffer from poor marketing campaigns, untimely releases or a critic-created narrative that they were atrocities? Each movie’s rollout was fairly conventional. And each was released in May (May 12 for “King Arthur,” May 24 for “Baywatch”), around the same time as “Snatched” (May 12), “Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales” (May 26), and “Captain Underpants” and “Wonder Woman” (June 2). The two movies may have been lost in the torrent of big budget studio films released from mid-May to early June. But the bad buzz around the films, reflected on Rotten Tomatoes, would explain why they were lost.

So, though the issue for Hollywood as a whole is not Rotten Tomatoes, you can’t blame a movie executive for being on a “mission to destroy the review-aggregation site.” Rotten Tomatoes could very well play a big part in killing given tentpoles — just as it could boost others. On the other hand, that sort of simpleminded thinking — DESTROY — is part of what’s plaguing Hollywood. The studios behind “King Arthur” and “Baywatch” have been watching too many of their own shallow bad-versus good films if they think they’ll solve their problems by crushing the enemy out of existence. Kill Rotten Tomatoes, and watch as Metacritic (a separate review aggregator that doesn’t currently have the reach of Rotten Tomatoes) or some other site fills the niche.

But there’s a more nuanced resolution. Studios ostensibly want the same thing as Fandango: to sell movie tickets, and to do so sustainably. Pulling one over on fans may prop up the box office today, but the sour experience will make moviegoers less inclined to return to the theater. So movie executives and Fandango should want some way for fans to guarantee their own satisfaction (like a review aggregator). But their priority should be to prop up a different metric. Instead of advertising critics’ scores, Rotten Tomatoes should trumpet films’ Audience Score. The Audience Score, rather than the Tomatometer, should be the number that pops up when someone searches for a film on Google or Fandango. That minor change would solve Hollywood’s Rotten Tomatoes problem. As for the bigger, long-term downward trend in ticket sales? There’s your sequel.

“It” deserves an array of Oscars

Bill Skarsgard plays It/Pennywise the Dancing Clown in the film "It" (Credit: Getty/Robyn Beck)

For the record, the genesis of this article pre-dated the announcement that “It” had broken box office records. Yet the fact that it has earned an awe-inspiring $117 million in its opening weekend only reinforces the conclusion that I reached after seeing the movie on opening night:

“It” needs to win Oscars. Like, all of the Oscars.

This is a tall order, mainly because the Academy is notoriously snobby when it comes to recognizing horror films, outside of a handful of select categories (special effects, costume design, etc.) “The Silence of the Lambs” is the great exception to this rule, sweeping the Big Five awards in 1991 (Best Picture, Best Director for Jonathan Demme, Best Actor for Anthony Hopkins, Best Actress for Jodie Foster and Best Adapted Screenplay for Ted Tally), but in many ways it is more of a thriller than a straightforward horror film. It doesn’t have any supernatural elements and could just as easily pass for a crime drama.

“It,” on the other hand, is steeped in the supernatural. Based solely on the movie (which is what will be judged by the Academy, after all), it is the story of a shapeshifting otherworldly entity, one that prefers to take the form of a creepy clown but can change into anything that might marinate the meat of little children in their own fear. On the surface, this is precisely the type of schlocky premise that turns off the highbrows at Oscar time.

Yet “It” transcends the often schlock-laden genre and is one of the best of 2017 and deserves to be recognized for its achievement in at least four categories — the award for best director goes to Andy Muschietti; best supporting actor goes to Finn Wolfhard as Richie Tozier, Bill Skårsgard gets best actor for his portrayal of Pennywise the Dancing Clown. Utimately, “It” deserves best picture.

The first two categories are the easiest to explain. “It” has the daunting task of merging a poignant and realistic coming-of-age story with a scary horror film, and that is no mean feat. The original 1990 miniseries was far more effective at being scary (mainly because Tim Curry delivered iconic performance as Pennywise), while the Netflix series “Stranger Things” (which “It” is clearly trying to emulate, at least stylistically) is better as a coming-of-age tale than a horror flick. “It,” on the other hand, balances these two so adroitly that one almost takes the meld for granted. This is primarily due to Muschietti’s direction. While all of the child actors are superb, Wolfhard’s performance is the real standout — the one who evoked the most impact from the audience (his quips regularly led to bursts of applause from the audience), and the one who left the deepest impression — and his character Tozier provides the narrative glue.

Indeed, he was surpassed by only one actor in the entire cast — Skårsgard himself.

Like Hopkins in “The Silence of the Lambs” or Heath Ledger as Joker in “The Dark Knight” — both of whom rightly won Oscars themselves — Skarsgard gives a performance that chills you right to your core. It’s a melange of subtle quirks: The tinny tone he uses when trying to sound child-like, the menacing arching and lowering of his eyebrows, his loping body mannerisms that manage to be simultaneously intimidating and sickly comical. Even though the audience isn’t given much backstory for Pennywise, Skårsgard is able to convey volumes through his interactions with the children. He is at once playful and contemptuous toward them, never questioning his own superiority, yet energized by the thrill of the hunt.

He is also surprisingly vulnerable. Near the end (spoiler alert), after the kids have defeated him, he begins literally quaking and whimpering at his impending defeat. He manages to escape to fight another day, of course, but before doing so, there is real fear in his eyes and demeanor. And yet . . . and yet it, isn’t the fear of one who is necessarily afraid of dying. One senses from Skårsgard’s expressions less of a physical terror, like the one he gives to the children, than an existential one. There is something fascinating and profound in the way Pennywise cowers before the children, akin to what you would expect when your entire sense of identity has been potentially exposed as an obnoxious lie.

If Skårsgard has given a performance of this magnitude in the service of a biopic, or a historical epic, or a Shakespearean melodrama, there would be little doubt that an Oscar nod was in his future. The only factor potentially working against him is that he happens to have done so for a horror film.

This brings me to the final category — Best Picture. Because the 2017 film season isn’t over yet, it is too soon to say whether “It” is the best film of the year, but the film is, without question, the best one I’ve seen so far. There is an intangible quality that separates the truly great movies from the merely good ones. It can be deconstructed and quantified to a degree, but in the end there is a gravity that elevates the future classics above their counterparts. As I noticed in the reactions of the audience members around me, as well as from my own heart, “It” possesses that last quality in spades.

So will “It” wind up joining “The Silence of the Lambs” in that rarefied realm of beloved horror films that are recognized by the Academy? That’s impossible to say right now, but if this is to happen, the process must begin by audiences clamoring for it. That is why I’m writing this not so much as a critic but as an ordinary moviegoer, experiencing Proustian transport via an old-fashioned scary movie executed by a team of filmmakers and actors at the top of their game.