Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 301

September 14, 2017

The only safe email is text-only email

(Credit: AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

It’s troubling to think that at any moment you might open an email that looks like it comes from your employer, a relative or your bank, only to fall for a phishing scam. Any one of the endless stream of innocent-looking emails you receive throughout the day could be trying to con you into handing over your login credentials and give criminals control of your confidential data or your identity.

Most people tend to think that it’s users’ fault when they fall for phishing scams: Someone just clicked on the wrong thing. To fix it, then, users should just stop clicking on the wrong thing. But as security experts who study malware techniques, we believe that thinking chases the wrong problem.

The real issue is that today’s web-based email systems are electronic minefields filled with demands and enticements to click and engage in an increasingly responsive and interactive online experience. It’s not just Gmail, Yahoo mail and similar services: Desktop-computer-based email programs like Outlook display messages in the same unsafe way.

Simply put, safe email is plain-text email — showing only the plain words of the message exactly as they arrived, without embedded links or images. Webmail is convenient for advertisers (and lets you write good-looking emails with images and nice fonts), but carries with it unnecessary — and serious — danger, because a webpage (or an email) can easily show one thing but do another.

Returning email to its origins in plain text may seem radical, but it provides radically better security. Even the federal government’s top cybersecurity experts have come to the startling, but important, conclusion that any person, organization or government serious about web security should return to plain-text email:

“Organizations should ensure that they have disabled HTML from being used in emails, as well as disabling links. Everything should be forced to plain text. This will reduce the likelihood of potentially dangerous scripts or links being sent in the body of the email, and also will reduce the likelihood of a user just clicking something without thinking about it. With plain text, the user would have to go through the process of either typing in the link or copying and pasting. This additional step will allow the user an extra opportunity for thought and analysis before clicking on the link.”

Misunderstanding the problem

In recent years, webmail users have been sternly instructed to pay perfect attention to every nuance of every email message. They pledge not to open emails from people they don’t know. They say they won’t open attachments without careful vetting first. Organizations pay security companies to test if their employees make good on these pledges. But phishing continues — and is becoming more common.

News coverage can make the issue even more confusing. The New York Times called the Democratic National Committee’s email security breach somehow both “brazen” and “stealthy,” and pointed fingers at any number of possible problems — old network security equipment, sophisticated attackers, indifferent investigators and inattentive support staff — before revealing the weakness was really a busy user who acted “without thinking much.”

But the real problem with webmail — the multi-million-dollar security mistake — was the idea that if emails could be sent or received through a website, they could be more than just text, even webpages themselves, displayed by a web browser program. This mistake created the criminal phishing industry.

Engineered for danger

A web browser is the perfect tool for insecurity. Browsers are designed to seamlessly mash together content from multiple sources — text from one server, ads from another, images and video from a third, user-tracking “like” buttons from a fourth, and so on. A modern webpage is a patchwork of third-party sites, which can number in the dozens. To make this assemblage of images, links and buttons appear unified and integrated, the browser doesn’t show you where the pieces of a webpage come from — or where they’ll lead if clicked.

Worse, it allows webpages — and thereby emails — to lie about it. When you type “google.com” into your browser, you can be reasonably sure you will get Google’s page. But when you click a link or button labeled “Google,” are you actually heading to Google? Unless you carefully read the underlying HTML source of the email, there are a dozen ways your browser can be manipulated to trick you.

This is the opposite of security. Users can’t predict the consequences of their actions, nor decide in advance if the potential results are acceptable. A perfectly safe link might be displayed right next to a malicious one, with no apparent difference between them. When a user is faced with a webpage and the decision to click on something, there is no reasonable way to know what might happen, or what company or other party the user will interact with as a result. By design, the browser hides this information. But at least, when browsing the web, you can choose to start at a trusted site; webmail, however, delivers an attacker-made webpage right into your mailbox!

The only way to be sure of security in today’s webmail environment is to learn the skills of a professional web developer. Only then will the layers of HTML, Javascript, and other code become clear; only then will the consequences of a click become known in advance. Of course, this is an unreasonable level of sophistication to require for users to protect themselves.

Until software designers and developers fix browser software and webmail systems, and let users make informed decisions about where their clicks would lead them, we should follow the advice of C.A.R. Hoare, one of the early pioneers of computer security: “The price of reliability is the pursuit of the utmost simplicity.”

Safe email is plain-text email

Companies and other organizations are even more vulnerable than individuals. One person needs only to worry about his or her own clicking, but each worker in an organization is a separate point of weakness. It’s a matter of simple math: If every worker has that same 1 percent chance of falling for a phishing scam, the combined risk to the company as a whole is much higher. In fact, companies with 70 or more employees have a greater than 50 percent chance that someone will be hoodwinked. Companies should look very critically at webmail providers who offer them worse security odds than they’d get from a coin toss.

As technologists, we have long since come to terms with the fact that some technology is just a bad idea, even if it looks exciting. Society needs to do the same. Security-conscious users must demand that their email providers offer a plain-text option. Unfortunately, such options are few and far between, but they are a key to stemming the webmail insecurity epidemic.

Mail providers that refuse to do so should be avoided, just like back alleys that are bad places to conduct business. Those online back alleys may look eye-pleasing, with ads, images and animations, but they are not safe.

This article was written in collaboration with cybersecurity researcher and developer Robert Graham.

This article was written in collaboration with cybersecurity researcher and developer Robert Graham.

Sergey Bratus, Research Associate Professor of Computer Science, Dartmouth College and Anna Shubina, Post-doctoral Associate in Computer Science, Dartmouth College

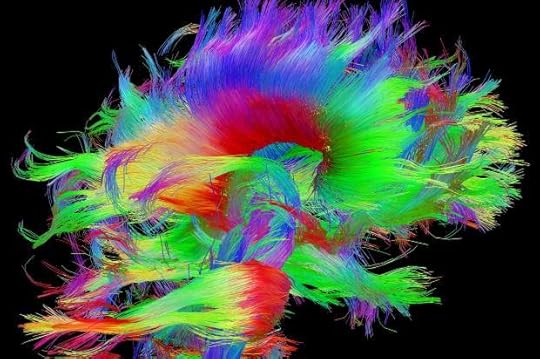

3 famous philosophers who took psychedelics and pronounced it mind-changing

(Credit: Courtesy of the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging and Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Consortium of the Human Connectome Project - www.humanconnectomeproject.org, www.loni.usc.edu via AP)

Despite being prohibited in the U.S. for nigh on half a century now, psychedelics are making a comeback. Researchers are studying their use in the treatment of psychological disorders, microdosing LSD has become an abiding phenomenon and there’s even a move to legalize magic mushrooms afoot in California.

Still, because of their prohibited status, research on the benefits of psychedelics is in its infancy. But not everyone feels the need to wait for clinical trials and peer-reviewed studies before jumping on the psychedelic bandwagon. The serious ponderers over at Big Think have been thoughtful enough to put together the following list of philosophers and scientists who tried psychedelics and pronounced them worthwhile.

1. Gerald Heard

The British author and polymath was a psychedelic pioneer, trying LSD for the first time in the mid-1950s. He saw the drug as a catalyst for spiritual insight, and his private proselytizing of his intellectual peers cracked open the door the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s, convincing such counterculture luminaries as Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary to follow in his footsteps.

“There are the colors and the beauties, the designs, the beautiful way things appear,” Heard told an interviewer. “But that’s only the beginning. Suddenly you notice that there aren’t these separations. That we’re not on a separate island shouting across to somebody else trying to hear what they are saying and misunderstanding. You know. You used the word yourself: empathy.”

2. Alan Watts

The British philosopher played a huge role in bringing the ideas of Eastern philosophy to a Western audience that, by the 1960s, was increasingly receptive to novel spiritual ideas. But this spiritual seeker didn’t limit himself to Zen Buddhism; in his quest for enlightenment, he experimented with LSD, among other drugs, which he argued gave people “glimpses” of a greater spirituality and ground their connections to the universe.

But psychedelics are only a means to an end, he cautioned: “If you get the message, hang up the phone. For psychedelic drugs are simply instruments, like microscopes, telescopes, and telephones. The biologist does not sit with eye permanently glued to the microscope, he goes away and works on what he has seen.”

3. Aldous Huxley

Best known as the author of “Brave New World”, this British author and philosopher experimented with mescaline in the 1950s and so believed in psychedelics that, knowing the end was near in 1963, he went to his death tripping on LSD.

Huxley published his thoughts on psychedelics in two books, “The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell”, where he argued that the drugs allowed people to see the world “as is” rather than the mundane reality we typically experience. Viewing the world through the psychedelically enhancing “mind at large” would benefit many people, he wrote.

But Huxley also was also something of an intellectual elitist; he argued that drugs like LSD were too much for the masses and should be used only by “the best and brightest.” He also cautioned that the psychedelic experience was not enlightenment, but only a tool to help intellectuals trapped by their attachments to words and symbols.

Wyclef Jean imagines himself as president

“Donald Trump, he won the competition,” singer/songwriter Wyclef Jean crooned to the cords of his 2010 ballad “If I was President.”

“Hillary Clinton, she put up a competition. Bernie Sanders, he was taken from the competition,” Jean sang, tailoring the track to reflect the current political climate on an acoustic set for “Salon Stage.”

After Jean’s remixed introduction recapping the 2016 presidential election, he went into the song’s lyrics—a hit song from his album “Welcome to Haiti/Creole 101.”

Jean joined “Salon Stage” ahead of the release of his new album, “Carnival III: The Fall and Rise of a Refugee,” arriving September 15. The album is Jean’s seventh solo album and marks 20 years since the first installment in the “Carnival” album series.

“Carnival III is more than just an album,” Jean said. “It’s about putting music together that will outlive me and live on for generations to come.”

Jean’s music has always felt politically relevant and long held a poignant message that goes beyond sonic innovation. “If I was President” follows this trend:

Instead of spending, billions on the war

I can use that money, so I can feed the poor

Cuz I know some so poor, when it rains that’s when they shower

Screaming fight the power

That’s when the vulture devour

Jean revealed to Salon that leadership was something for which longed in his home base of Haiti. He explained that after the release of “Carnival II” in 2007, his retreat from music was because “I went to go help my country,” he told Salon’s Amanda Marcotte. “I wanted to be president of my country at the time, help move it forward.” In 2010, Haiti’s electoral council disqualified Jean’s presidential campaign bid.

Watch the full “Salon Stage” performance on Facebook.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

Grant Hart, Hüsker Dü’s drummer and inspiration for a rock generation, is dead at 56

Grant Hart, center, in Hüsker Dü

Overnight Thursday, news broke that Grant Hart, a versatile musician who’s best known as the drummer/vocalist/co-songwriter in ’80s underground legends, had passed away. He was 56. The Star Tribune reported that the musician had recently received a diagnosis of terminal liver cancer, with his former Hüsker Dü bandmate Greg Norton adding that Hart was admitted to the hospital on Wednesday night.

News of his death was wrenching. Just last week, the reissue label Numero Group announced “Savage Young Dü,“ an extensive (and long-awaited) three-CD boxed set encompassing Hüsker Dü’s ferocious early years. Each member of the trio contributes to that ferocity, but Hart’s drumming kept the band’s legendary speeds topped off. In fact, vintage Hüsker Dü live footage shows Hart as the eerily steady nexus of this hurricane-force sound and speed—a mighty drummer who somehow manages to be both feral and calm, and nonchalant about the power he wields.

Still, figuring out where to begin with Hart’s musical talents is daunting. He was that rarest of drummer breeds — one who also sings lead on occasion, while playing — and the songs he contributed to Hüsker Dü were brisk and to the point. Early on, this led to the chilling and harrowing “Diane,” with its lyrics based on a real-life murder. Later, Hart honed his knack for emotional brutality. The roiling, acoustic-based “Never Talking To You Again” is a crisp and no-holds-barred kiss-off toward an ex, while “Don’t Want To Know If You Are Lonely” is about the tortured aftermath of a breakup that’s difficult to let go. “Please leave your number and a message at the tone,” the song ends. “Or you can just go on and leave me alone.”

Sonically, Hart’s songwriting went in scattered directions as Hüsker Dü progressed beyond hardcore punk, although his direct nature and melodic gifts always shone through. “Diane” is a scabrous and harrowing metallic drone; “Green Eyes” and “Pink Turns to Blue” are noise-coated power-pop; and “The Girl Who Lives On Heaven Hill” is punkish and freewheeling. “Books About UFOs” is even a positively jaunty, ’60s pop-kissed number. No matter what the style, however, Hart’s ability to craft indelible hooks was almost supernatural.

This ability to shapeshift between genres became even more pronounced when Hart went solo after Hüsker Dü’s 1988 breakup. The records he released under his own name and with the band Nova Mob are defiantly uncategorizable. Over the years, Hart dabbled in shirring psych-pop (“2541″), dazzling psych-drone (Nova Mob’s pulsating “Shoot Your Way to Freedom”), Elvis Costello-esque power-pop (the organ-stung “Now That You Know Me”) and shambling indie-rock (“Narcissus Narcissus”). On his last solo album, 2013’s “The Argument,” Hart sounds like a weathered and mischievous raconteur — his vocals are lilting and folksy, like a clear-headed Dylan — as he waltzes through lo-fi glam, keyboard-iced lounge croons and theatrical rock.

And, really, that’s barely scratching the surface. Hüsker Dü’s influence on modern rock music is impossible to overstate. Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong said as much in an Instagram remembrance, that his own trio exists because of Hüsker Dü, and groups such as Foo Fighters and Pixies owe obvious debts to the band.

But Hart’s influence is best exemplified by the fact that musicians shared so many different songs by him, culled from different eras, once news of his death broke. “Grant Hart wrote some of the songs that matter the most to me,” Hold Steady’s Crag Finn tweeted, in addition to a clip of the shambolic, “It’s Not Funny Anymore.” Ryan Adams posted the “Zen Arcade” fuzzbomb “Somewhere,” and tweeted, “RIP Grant Hart. Your music saved my life. It was with me the day I left home. It’s with me now. Travel safely to the summerlands.”

The Posies, meanwhile, tweeted their buzzsawing 1996 song “Grant Hart,” a loving nod to Hüsker Dü that actually led to Ken Stringfellow and Jon Auer backing up their hero. Sean Nelson of Harvey Danger posted his stark, piano-based cover of “Sorry Somehow“ and wrote, “I am not a partisan about Hart vs. Mould. I love them both a lot, but Grant’s songs had a slight edge in the vulnerability department.” Jon Wurster, who’s drummed in Hüsker Dü guitarist/vocalist Bob Mould’s solo band for years, tweeted the solo song “The Main” and wrote, “His drumming was so incredible I feel like a fraud when we play Husker Du songs. AND he could write & sing like this.”

In his own lovely statement, Mould called Hart “a gifted visual artist, a wonderful story teller and a frighteningly talented musician,” and remembered their “amazing decade” together in the influential band. “We made amazing music together. We (almost) always agreed on how to present our collective work to the world. When we fought about the details, it was because we both cared. The band was our life.”

That care and vulnerability no doubt explains why Hart’s death feels so devastating. His music never shied away from hard truths or the heartbreaking side of life, even if these things were difficult to hear, because Hart knew there wasn’t always a silver lining. That made his music enormously relatable and endearing, as he voiced the kinds of anxiety-inducing things that keep people awake in the middle of the night. But even the darkest moments had smudges of beauty, Hart’s way of leaving the door cracked, just in case, for better days and brighter possibilities.

Bernie’s healthcare solution has a major flaw, and it’s an open invitation for critics

Presidential candidate, Bernie Sanders prepares to speak for a video to supporters at Polaris Mediaworks on Thursday June 16, 2016 in Burlington, VT. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post via AP, Pool) (Credit: AP)

The good news is Bernie Sanders and other senators will introduce a “Medicare-for-All, single-payer healthcare” legislation this week. The bad news is their proposal won’t say how to pay for universal health care for all Americans.

“Unless something changes, which I’m [still] hoping, this confirms the two nastiest judgments of critics of single-payer,” said Gerald Friedman, a University of Massachusetts economist and expert on financing nationwide universal healthcare coverage. “The liberals are saying, ‘The single-payer community doesn’t know how to do policy, so they need to come to us, the wonks, and we’ll tell them how to do it’ — and in the process, we won’t do single payer, we’ll do something else. And the conservatives who say, ‘Single payer will be so expensive that even its supporters are scared to talk about how much it will cost and how much it will raise your taxes.”

“If you fill in the blanks [on how pay for nationwide care], then you are going to have an argument,” Friedman continued. “You are going to have an argument with people about how much this will go up; how much that will go up; how much you will be able to control this cost or that cost. You’ll have an argument. And if you don’t fill in the blanks on the financing, then you’re going to just leave the whole space to them [opponents]. They’ll say whatever they want.”

Friedman’s warning, call it loyal opposition, comes at a poignant moment. Progressives have long sought a national health system, long before Sanders ran for president and popularized the idea. It got sidelined in 2017 over GOP threats to destroy Obamacare and gut Medicaid, the state-run health plan for the poor.

But the GOP’s “repeal and replace” implosion wasn’t the only big health policy debacle this year. In Democrat-controlled California, a proposal for a state single-payer system was sidelined. It passed its state Senate, but only after supporters said the state Assembly would fill in its financing options.

Days before the Senate acted, the bill’s top advocate, the California Nurses Association, released a plan to raise the $100-plus billion in revenue needed, offering two progressive tax increases. But Senate staffers got ahead of the nurses and said a state single-payer system would require doubling the payroll tax. That scary scenario, which was not the only revenue option, paved the way for conservative Democrats in the state Assembly to kill the nurses’ proposal.

Friedman’s point is the Sanders bill is poised to repeat this same mistake — giving an opening to the status quo’s defenders to frame single payer as unaffordable, and more of a left-wing fantasy than a serious policy alternative. The economist, who has seen various versions of Sanders’ bill, said there is no reason to give opponents this open invitation, especially when there is plenty of academic literature discussing progressive revenue options.

“We have a bill, great. It would be even better if it was a full bill,” he said. “Here’s where they could go. There are a bunch of studies done on the state level [New York, California]. There’s a PNHP [Physicians for a National Program] study but also [David] Himmelstein and [Steffie] Woolhandler have a study in the Annals of Internal Medicine this year, estimating its costs.”

What are these studies’ revenue options, as well as on websites like Healthcare-Now.org, where Friedman is a board member. They involve a mix of options that move away from employers carrying the costs or individuals buying policies, which are pillars of the current system. There is raising state sales tax by a few points, taxing business revenues after the first $2 million—which exempts small business, taxing speculative financial transactions, increasing the payroll tax in tiers to protect low-wage earners, and increasing the income tax for people making more than $225,000 annually.

“People can go to that and fill in the blanks in the Bernie bill, because there’s a giant blank,” Friedman said. “If the Bernie bill gets any real attention, other people are going to fill in the blanks. And they are going to be nasty about it.”

“The insurance industry and the drug companies and the hospitals can afford to pay economists, and they will find good economists who will say ridiculous things — things that I consider ridiculous,” he said. “But without an answer from Sanders, that’s what’s going to come in. Just like the California Senate’s estimates, which were a bit high; but are not nearly as unreasonable as what Republicans are going to come in with — if it gets to that.”

On the other hand, Sanders’ bill may not be much more than a rallying cry for a grassroots movement before 2018’s elections. There’s little chance anything he proposes would get a hearing in this Congress. But even if that’s true, his proposal should not be a bumper sticker that hurts reform effort, including smaller steps.

“What can happen now?” Friedman said. “On the federal level and on the state level, we have to find intermediate steps. Things like Medicare for All [where enrollees pay premiums, deductibles and co-pays, and insurers sell policies covering its gaps], or Medicare for More, such as lowering the age of Medicare five years at a time… We are not going to be able to go ahead in one leap. This is too much money and too many [opposing] interests. We have to chip away at the interests.”

When progressives hear from Sanders, Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA, and Kamala Harris, D-CA, and many advocacy organizations later this week, they should heed what these political figures are promoting: pragmatic legislation or a political campaign. Even H.R. 676, the single-payer bill proposed by Rep. John Conyers, D-MI, tips its hat to including funding mechanisms, even if they are generic references to taxing the richest Americans.

Harvey and Irma aren’t natural disasters. They’re climate change disasters

Rescue boats fill a flooded street as flood victims are evacuated. (Credit: AP/David J. Phillip)

If you’re like me, you can’t stop yourself from watching the weather these days. And if you’re like me, you can’t help but think: Holy shit, it’s here.

Back-to-back hurricane catastrophes have plunged the United States into a state of national crisis. We’ve already seen one worst-case scenario in Texas: For the moment, Hurricane Harvey stands as the most costly natural disaster in U.S. history. And now there’s Irma, which has wreaked havoc across the entirety of Florida, America’s most vulnerable state. In just two weeks, the U.S. could rack up hundreds of billions of dollars in losses.

Make no mistake: These storms weren’t natural. A warmer, more violent atmosphere — heated up by our collective desire to ignore the fact that we live on a planet where such devastation is possible — juiced Harvey and Irma’s destruction.

Houston and South Florida have long been considered two of our most vulnerable regions, carved out of swamps in some of the most storm-prone parts of the Earth. Now they lay, at least partially, in ruins.

Lurking behind the horrific scenes of water rising above rooftops along swollen Texas bayous and palm trees snapping in front of battered beachfront condos is this stark reality: Climate change doesn’t “cause” disasters like this, but it most certainly is making them worse.

It’s scary to watch this play out in real time. People’s lives and our landscapes are being altered. This is not a “new normal.” There is no more normal.

What are the most compelling facts on climate change & hurricanes you’ve seen recently? That fit in a tweet? cc: @EricHolthaus @KHayhoe

— Anna Jane Joyner (@annajanejoyner) September 6, 2017

The effects of this new phase in our new climate reality reach far beyond the southeastern United States. Devastating floods across India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sierra Leone, Niger, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nigeria in recent weeks collectively killed hundreds more than Harvey has and Irma likely will, combined.

A massive complex of wildfires is burning millions of acres across the North American West, with a smoke plume stretching coast-to-coast. On September 1, the day a petrochemical plant outside Houston exploded amid Harvey’s floodwaters, San Francisco recorded its warmest day in history — a blistering 106-degrees Fahrenheit — hotter than oft-scorching Tucson, Arizona.

Each of these events, individually, have a connection to the warming atmosphere. Collectively, they’re a klaxon siren that something is very, very wrong.

Of course, bad luck also played a role in the last two weeks. It’s hard to separate the two. Harvey, a Category 4 hurricane at landfall, oriented itself perfectly as it developed to maximize the rainmaking power of an overheated Gulf of Mexico.

Irma, one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded on Earth, hopscotched through the Caribbean, making landfall on half a dozen islands at peak strength. And a third storm, Jose, also reached Category 4 strength, prompting a complete evacuation of the tiny Caribbean island of Barbuda — just four days after it was almost completely destroyed by Irma.

Some weather models now show Jose could make a loop in the middle of the Atlantic this week. If it heads back toward land, Florida is a possible destination.

So yeah, bad luck. But this is also the first time in history that the Atlantic has seen back-to-back-to-back hurricanes of Category 4 or higher. At one point on Friday, Irma and Jose both had estimated winds of 150 mph — strong enough to pulverize even well-built houses. Never before have two hurricanes of that strength existed simultaneously, much less assaulted the same piece of land.

There’s so much happening today in this view from NOAA’s new weather satellite, GOES-R. pic.twitter.com/31ZgmZ7I9l

— Robinson Meyer (@yayitsrob) September 8, 2017

We knew a time like this was coming. In the U.S. government’s recent Climate Science Special Report — painstakingly assembled by 13 federal agencies from the work of thousands of scientists around the world and then leaked to the New York Times for fear of censorship by the Trump Administration — the authors were clear:

Hurricanes, especially the strongest ones, are going to get worse in the future.

Both physics and numerical modeling simulations indicate an increase in tropical cyclone intensity in a warmer world, and the models generally show an increase in the number of very intense tropical cyclones. For Atlantic and eastern North Pacific hurricanes and western North Pacific typhoons, increases are projected in precipitation rates and intensity. The frequency of the most intense of these storms is projected to increase in the Atlantic and western North Pacific and in the eastern North Pacific.

With each year that passes, we’re locking in an extension of this horrific, tragic moment in human history — a time period between when the effects of climate change become blindingly obvious and when we actually do something meaningful about it. Scientists have warned us for decades about worsening weather. But many of our leaders fail to act.

In his 2009 memoir, climate scientist James Hansen warned of the “storms of my grandchildren.” Turns out, he was still alive to see them. Climate writer Alex Steffen calls this new era, which feels outside the realm of normal existence, a “xenotopia,” or strange world.

Every day, British naturalist writer Robert MacFarlane uses his Twitter account to define a new word that relates to our new reality. (Friday’s was “caochan” — “a stream so slender or overgrown it can scarcely be seen.”) Today we are already mourning a destruction that has yet to happen — a phenomenon the Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht calls “solastalgia.”

There’s evidence that extreme weather, no matter the magnitude, won’t change our politics anytime soon. Predictably and understandably, Texans and Floridians are already focused on rebuilding. But missing from the conversation right now is a frank discussion about the near future.

Destructive storms like Harvey and Irma will only become more common. Accepting that fact — and talking about the radical change necessary to reverse this trend — is the most important thing we can do right now.

Those conversations could alter the way we build our cities, so we put fewer people in harm’s way. They could begin to force our government to rethink its habit of subsidizing the corporations and industries that got us into this mess.

We’re not talking about far-flung creatures and concepts like polar bears and melting ice caps anymore. We’re talking about the destruction of lives and places where many of us live or have visited.

At times like these, politicians like to talk about the American ability to come back stronger than ever. What if, this time, we considered planning ahead so we don’t need to come back at all?

5 things that have changed about FEMA since Katrina — and 5 that haven’t

(Credit: Reuters/Jason Reed)

Hurricanes, wildfires and earthquakes — is the Federal Emergency Management Agency ready for the new era of disasters?

I’m a professor of public administration and policy at Virginia Tech, and I’ve written a book explaining why expectations of this agency are so high — unrealistically so.

After Hurricane Andrew hit Florida in 1992, the emergency manager of Dade County, Florida famously asked the media, “Where in the hell is the cavalry?” after her requests for aid from FEMA went unanswered. Picking up on the anger, some members of Congress wanted to abolish the agency as punishment for its poor response.

FEMA survived, but it came under blistering criticism again after Hurricane Katrina killed 1,833 people and caused more than US$100 million in damage.

The response to Hurricanes Harvey and Irma has gone much more smoothly — at least so far. So what has changed with FEMA since Katrina?

5 things that have changed

1. Leadership

Presidents learned the importance of placing experienced emergency managers in charge of FEMA. During the Katrina disaster, President George W. Bush told FEMA Director Michael Brown, “you’re doing a heck of a job.” Ten days later, Brown resigned in disgrace.

Brown was only one of the agency’s problems at the time. An academic analysis found that turnover among FEMA leadership and appointees without sufficient qualifications contributed to the agency’s halting response. Before joining FEMA, Brown supervised judges at horse shows. He joined FEMA through a connection with his college roommate, Joe Allbaugh, who was President Bush’s first campaign manager and FEMA director.

Since Brown, presidents have appointed FEMA directors with emergency management experience. Current FEMA Director Brock Long was director of the Alabama Emergency Management Agency, and had previously worked at FEMA.

2. Community perspective

One of the signature initiatives of FEMA during the Obama administration was the “whole community” approach, intended to involve the private sector, community groups and individual citizens in disaster preparedness. The whole community approach was intended to harness the assets of civil society, draw attention to disaster resilience and improve coordination.

For example, businesses played a key role in the Harvey response. Individual store owners opened as soon as they could to help distribute what people needed. Texas grocer H.E.B. sent convoys to the affected region. The whole community approach is not the only driver of private sector involvement, but it reflects FEMA’s commitment to approaching the private sector and groups of concerned citizens as partners rather than as subordinates in disaster response.

3. Cell phones and the web

Social media inspired collaborative, bottom-up responses that we have only begun to understand. During Katrina, social media was a hobby of techie students. Facebook was not yet available beyond universities. Today, government agencies and rural Texans and Floridians use social media. People found out which shelters were open and who needed help during the storm through texts and tweets. Social media also drives the government’s response because government responds to what’s on CNN. Imagine if pictures of the dangerous conditions at Memorial Hospital, hidden from news cameras during Katrina, had been circulated on the internet and broadcast on television. Lives might have been saved.

4. Going beyond rebuilding

After Katrina, resilience replaced sustainability as the organizing concept in disaster management. Government agencies and private foundations used the term as a rallying cry to focus efforts on how to prepare for inevitable disasters rather than just avoid them. The Rockefeller Foundation even funded resilience officers in local government beginning in 2013.

At its best, resilience refers to the idea that communities can do more than just rebuild. They can invest in levees, canals, wetlands and insurance to adapt to a changing normal.

At its worst, resilience is an empty term that gives the impression that cities can bounce back if only they try hard enough. In truth, low-lying regions will have to decide to limit construction and inform people about true risks — both difficult in the face of a worldwide trend toward urbanization and pressures to develop land and make money in the short term.

5. Early movers

After Katrina, Congress gave FEMA greater authority to move resources to a disaster zone before a storm rather than wait for formal requests from governors after the event. Before Harvey, truckloads of food, water and tents were positioned outside of the flood zone, waiting for rains to subside so they could be sent to the recovery zone. Supplies from FEMA and the Department of Defense arrived within hours, not days, after the rains ended. FEMA’s pop-up hospital drew praise.

5 things that are the same

Despite the lessons learned, some things have not changed.

1. Agency misfit

FEMA is still a part of the Department of Homeland Security — an agency that has other priorities. The department was focused on terrorism during Katrina, and now its chief policy priorities are immigration and borders.

2. Still not the cavalry

Neighbors, city and county governments, and then the state are the first responders, not the federal government. Even at the federal level, FEMA primarily coordinates responses led by other agencies like defense, housing and agriculture. Meanwhile, businesses, nonprofits and even individuals with bass boats mounted their own response.

3. Limited powers

Decisions about land use, zoning and development are made at the state and local level, not by FEMA. State and local emergency managers have very little pull over development, and changing the building stock to strengthen 100-year-old homes or make wise investments in new ones requires a larger effort.

4. Inequality matters

Socioeconomic status and vulnerability still shape response. People with money are able to evacuate themselves, or return home and rebuild more quickly. People without financial resources, jobs or social connections face greater obstacles to returning to a normal life, and they need help.

5. Timing matters

The best time to prepare for the next disaster is immediately after the current one. Now is the time to communicate true flood risks through flood mapping, strengthen building and zoning guidance, organize community planning efforts to know what to do when the worst happens, and build new infrastructure to send water out of vulnerable areas. FEMA can be a partner in these efforts, but it requires leadership from politicians and bureaucrats at all levels of government. Until then, people will settle in risky places without reducing their vulnerability to storms, making the next disaster even more likely than the last.

The best time to prepare for the next disaster is immediately after the current one. Now is the time to communicate true flood risks through flood mapping, strengthen building and zoning guidance, organize community planning efforts to know what to do when the worst happens, and build new infrastructure to send water out of vulnerable areas. FEMA can be a partner in these efforts, but it requires leadership from politicians and bureaucrats at all levels of government. Until then, people will settle in risky places without reducing their vulnerability to storms, making the next disaster even more likely than the last.

Patrick Roberts, Associate Professor, Virginia Tech

September 13, 2017

Is the new iPhone designed for cybersafety?

As eager customers meet the new iPhone, they’ll explore the latest installment in Apple’s decade-long drive to make sleeker and sexier phones. But to me as a scholar of cybersecurity, these revolutionary innovations have not come without compromises.

Early iPhones literally put the “smart” in the smartphone, connecting texting, internet connectivity and telephone capabilities in one intuitive device. But many of Apple’s decisions about the iPhone were driven by design – including wanting to be different or to make things simpler – rather than for practical reasons.

Many of these innovations – some starting in the very first iPhone – became standards that other device makers eventually followed. And while Apple has steadily strengthened the encryption of the data on its phones, other developments have made people less safe and secure.

The lights went out

Among Apple’s earliest design decisions was to exclude an incoming email indicator light – the little blinking LED that was common in many smartphones in 2007. LEDs could be programmed to flash differently, even using different colors to indicate whom an incoming email was from. That made it possible for people to be alerted to new messages – and decide whether to ignore them or respond – from afar.

Its absence meant that the only way for users of the iPhone to know of unread messages was by interacting with the phone’s screen – which many people now do countless times each day, in hopes of seeing a new email or other notification message. In psychology, we call this a “variable reinforcement mechanism” – when rewards are received at unpredictable intervals – which is the basis for how slot machines in Las Vegas keep someone playing.

This new distraction has complicated social interactions and makes people physically less safe, causing both distracted driving and even inattentive walking.

Email loses its head, literally

Another problem with iOS Mail is a major design flaw: It does not display full email headers – the part of each message that tells users where the email is coming from. These can be viewed on all computer-based email programs – and shortened versions are available on Android email programs.

Cybersecurity awareness trainers regularly tell users to always review header data to assess an email’s legitimacy. But this information is completely unavailable on Apple iOS Mail – meaning even if you suspect a spear-phishing email, there is really no way to detect it – which is another reason that more people fall victim to spear-phishing attacks on their phones than on their computers.

Safari gets dangerous

The iOS web browser is another casualty of iOS’s minimalism, because Apple designers removed important security indicators. For instance, all encrypted websites – where the URL displays that little lock icon next to the website’s name – possess an encryption certificate. This certificate helps verify the true identity of a webpage and can be viewed on all desktop computer browsers by simply clicking on the lock icon. It can also be viewed on the Google Chrome browser for iOS by simply tapping on the lock icon.

But there is no way to view the certificate using the iPhone’s Safari – meaning if a webpage appears suspicious, there is no way to verify its authenticity.

Everyone knows where you stand

A major iPhone innovation – building in high-quality front and back cameras and photo-sharing capabilities – completely changed how people capture and display their memories and helped drive the rise of social media. But the iPhone’s camera captures more than just selfies.

The iPhone defaults to doing something many smartphones now can do: including in each image file metadata with the date, time and location details – latitude and longitude – where the photo was taken. Most users remain unaware that most online services include this information in posted pictures – making it possible for anyone to know exactly where the photograph someone just shared was taken. A criminal could use that information to find out when a person is not at home and burglarize the place then, as the infamous Hollywood “Bling Ring” did with social media posts.

In the 10 years since the first iPhone arrived, cyberattacks have evolved and the cybersecurity stakes are higher for individuals. The main concern used to be viruses targeting corporate networks; now the biggest problem is attackers targeting users directly using spear-phishing emails and spoofed websites.

Today, unsafe decisions are far easier to make on your phone than on your computer. And more people now use their phones for doing more things than ever before. Making phones slimmer, shinier and sexier is great. But making sure every user can make cybersafe decisions is yet to be “Designed by Apple.” Here’s hoping the next iPhone does that.

Editor’s note: This article was updated at 7:10 p.m. on September 12, 2017, to clarify that the iPhone is not the only smartphone that saves location information in photos.

Editor’s note: This article was updated at 7:10 p.m. on September 12, 2017, to clarify that the iPhone is not the only smartphone that saves location information in photos.

A hurricane with only one victim can be a lesson for us all

Damage from Hurricane Irma (Credit: AP/Gerben Van Es)

There comes a time in most of our lives when it’s necessary to ask for help. We have witnessed such a time most recently with Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, slamming into Texas, Louisiana, Florida and up the east coast over the couple of weeks leaving death and hundreds of billions in destruction in their wakes. The thing is, it’s usually the case that we don’t ask early enough.

You probably missed it, but another storm arrived just about this time last year. Hurricane Lucian was so small that it wasn’t covered on CNN or the other cable networks, and well-named as its eye had only one target and resulted in only one victim: me. There I was, sitting out here near the end of Long Island, already awash in depression before the storm arrived. I was nearing 70 years in age, I couldn’t find regular work as a writer, I was dismissive of the relationships in my life that were good for me and neglectful of those who actually loved me, and so lost in my own little fogbank of self-pity, fear and rage that I had arrived at the bottom of one gin bottle naturally reached for another for shelter as the storm bore down. The thing was, I had known for months that I needed help, and I knew someone who was well-prepared and ready to provide it, but of course I hadn’t asked. Denial isn’t an adequate word. It was more like an aggressively active repudiation of reason and a personal assertion of self-indulgence and arrogance that I mistook for independence. With a storm on the way, I was an island.

So the next morning, oblivious to the clouds on the horizon and the winds building in force around me, I set off to join my friends downtown for our regular morning coffee klatch, and upon hitting the street was knocked down by the hurricane I had seen coming but had done absolutely nothing about. Stone cold drunk at 10 in the morning, I fell flat on my face. The next thing I knew, like the victims of other, actual, far deadlier hurricanes, I found myself lying on my backside staring up into a very bright light surrounded by the kinds of people who are called upon to help in such cases: cops and ambulance drivers and EMT’s and doctors and nurses wielding IV drips and oxygen and the steadying hand of professionalism that’s always there, always available when the time comes, and so well-established by decades of legal regulations and tens of thousands if not millions of taxpayer dollars and the goodwill of volunteers and professionals alike that we take for granted the help they stand ready to give.

The best and most accurate way to describe what happened to me afterwards is to say that the system worked. Because there is a “system,” isn’t there? It’s the system we have created for ourselves through the establishment of our government to provide for all of us when the time comes that we need help. Not when we actually ask for it. I never asked for help, remember? But help is there when we need it. It’s not there because the free market in the form of some corporation took advantage of the opportunity to make a profit, or even found within itself the good will to provide help gratis in such an emergency. Help is there because collectively we have seen fit as a society to exercise mutually agreed upon moral principles, to organize them through a political system we have as citizens put into place, and to effectuate them with administrative bodies and federal, or state, or county, or town officials we have agreed to tax ourselves to pay in order to provide the help they are tasked with rendering. It sounds complicated, but it’s really very simple. We act collectively through the mechanism of our government in order to provide for the common good. And I’m here to tell you as a victim of Hurricane Lucian, we ignore the fact that government isn’t the problem but rather the solution at our personal and collective peril.

Like other storms before, and like Harvey and Irma after, my storm passed. I had damaged myself with gin and suffered a serious concussion and after initial medical treatment, began a process of reconstruction which is still ongoing today. Some of my recovery was covered by programs such as Medicare that we have taxed ourselves in order to pay for. I am a grateful beneficiary of the governmental largess we voted into place decades ago, and newly reminded of how necessary this help is when we need it. My continuing recovery has been aided by friends and the fellowship of volunteer organizations that benefit me as much if not more than the help I got from professionals. I’m a lucky, lucky guy.

The equivalent programs which are coming into play in the wake of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are those administered by FEMA through its Disaster Relief Fund and National Flood Insurance Program; from HUD through Community Development Block Grants; the Small Business Administration’s disaster relief loans; even through the Army Corps of Engineers and the state administered but federally funded National Guard units that are aiding in storm rescue and recovery. FEMA alone estimates that as many as 500,000 citizens will file for disaster relief from Hurricane Harvey (equivalent estimates by FEMA for Irma are not yet available). It is anticipated that as much as $150 billion may be needed in federal relief from Harvey. The cost of damage relief for Hurricane Irma is valued at as much as $100 billion, and there may be losses as high as $200 billion more to the tourism trade and agriculture in Florida alone. Damage estimates for the storm in Caribbean islands are in the multi-billions as well, with the U.S. Virgin Islands of St. Thomas and St. Croix particularly hard hit and eligible for federal relief. Every story I’ve read on Harvey and Irma say that it will take communities years and years to recover. Some, like New Orleans after Katrina, may never recover fully.

But this isn’t just about the help available from the federal government after the storm. What about the kind of help I knew I needed before Hurricane Lucian but didn’t ask for? I’m sure glad the system was there to provide help to me after I had crashed and burned, but it was just plain fucking stupid of me not to have sought the help I needed beforehand. The same goes for the cities and states hit hard by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Federal “help” was there in the form of new Federal Risk Management Standards that would have mandated flood abatement for any new infrastructure funded by the federal government. But President Trump signed an executive order less than 10 days before Harvey hit reversing the planned Obama mandates, leaving flood prone areas like metropolitan Houston and most of low-lying Florida and other coastal areas without regulations on new construction. Just as plain fucking stupid as me, huh?

It’s even worse than that. Scientists have been warning for years that global warming is leading to warmer seas, stronger storms, larger and larger amounts of rain, and more and more coastal flooding. But do you think that the Republican governors and legislatures of vulnerable states like Texas, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina — all of which just got inundated over the last two weeks — have paid the scientists any mind? Not on your life, or the lives of their citizens they haven’t. It’s pure madness, is what it is, the equivalent of living in an area that receives regular and sustained rainfall and deciding not to build a roof on your house. Why do something expensive like that? So the genius planners in Houston have contended over the years as they permitted willy-nilly development in the almost total absence of building codes and the actual absence of zoning laws. Why not let that dangerous, stinking goddamned chemical plant spew its pollutants into the air right next to grade schools and junior highs in the neighborhood next door? They decided to live there! They can move if they want! Freedom! And those roofs tacked onto wood frame houses with nail guns and no hurricane strapping? Hell yes! You want a roof on your house that turns into a nice airfoil in winds above 85 miles per hour, more power to you! Let those roofs fly! Freedom!

This country is going to have to come to grips with the before-and-after thing and do it sooner rather than later. This applies not just to storm-proofing communities in hurricane alley, but to a lot of other things as well, such as the opioid “crisis.” The current “solution” seems to involve throwing money at the “problem” in the form of treatment for addiction in the absence of dealing with the manufacture, distribution and prescribing of the actual drugs themselves. Which makes the same sense as our way of dealing with storms, even after being hammered successively by Hurricanes Rita ($24 billion), Wilma ($24 billion), Katrina ($160 billion), Ike ($35 billion), and now Harvey and Irma estimated to eventually cost more than $300 billion combined.

But, my god! We don’t want to hamper “economic development,” do we? Stand in the way of the almighty free market? What could you be talking about? Why, trying to tell the Republican legislatures of states like Texas and Florida and Louisiana and Georgia and South Carolina that they should make a few plans and pass a few laws mandating the functional equivalent of galoshes and umbrellas for homes and infrastructure lying in the paths of savage beasts like Harvey and Irma is a bit like trying to tell me that I should have poured out that bottle of gin instead of taking shelter inside of it when the storm hit. Truly scary to think that an entire political party in this country is just as plain fucking dumb as I am, isn’t it?

“You don’t write like most women”: 5 authors on 5 exciting new books

For September, I posed a series of questions—with, as always, a few verbal restrictions—to five authors with new books: Eleanor Henderson (“The Twelve-Mile Straight”), Holly Goddard Jones (“The Salt Line”), Chelsea Martin (“Caca Dolce”), Celeste Ng (“Little Fires Everywhere”) and Gabriel Tallent (“My Absolute Darling”).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Gabriel Tallent: The search for strategies of resistance when resistance seems impossible and also the life-changing magic of tidying up.

Celeste Ng: Mothers and daughters — both biological and chosen. Where art and life intersect and how they speak to each other. What happens when good intentions run into personal discomfort. The dangers of thinking that plans and rules will save you, which is maybe the futility of believing you can really control anything. The (im)possibility of starting over.

Eleanor Henderson: Sharecroppers, bootleggers, midwives, a cotton mill, a lynching, poverty, paternity, family, community, the disease of Jim Crow, other diseases, white savior complex, twins.

Chelsea Martin: Specific tips and tricks for those who have allowed shitheads into their lives, facts and figures about being a shithead, lots of insight about shitheads. But also beauty, you know? The fleeting kind no one expects and then it’s gone and you forget what was ever beautiful. Also the more obvious kinds of beauty, which are also great. Plus, the age-old question: why? (re: family) and, on a related note, whhhyyyyyyyy?????

Holly Goddard Jones: Killer ticks.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Jones: Mexican drug cartels. Chocolate chip pumpkin muffins. Perinatal depression. Accidentally sitting in a chigger nest. Donald Trump. Zika.

Martin: I wanted to get through this interview without mentioning bagels but here we are, I guess. Bagels. Sourdough. Art I made a long time ago that I know I didn’t throw away but that’s nowhere to be found. Conversations that have been stuck in my head for twenty years. The need to be heard without speaking. Rye, somewhat.

Tallent: Waiting with a dying seal hauled up on the black sand beach to die, sitting a ways off from him, keeping the vultures away, watching the rising of the tide in a cove soon to be flooded, reading the work of a tragedian killed by a falling tortoise who’d reportedly been staying out of doors on account of a prophesy that he’d be killed by a falling object.

Ng: A very small sampling of the many things that influenced the book in one way or another: Amy Heckerling; the Shakers; growing up in Cleveland in the 1990s; an adolescence spent in suburbia; the 1997 World Series; “Luv Me Luv Me” by Shaggy and Janet Jackson; Cindy Sherman; parenting.

Henderson: My father’s stories about his childhood on a Georgia farm during the Great Depression; the Great Recession; FDR; a documentary about fetal development; photos by John Vachon, Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein, and other WPA photograhers; Brian Brown’s blog Vanishing South Georgia; music by Blind Willie McTell, Woody Guthrie, Abner Jay, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe; a gourd tree at the Georgia Agricultural Museum.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Henderson: Giving birth; Mom dying; nursing; teaching students; waking up at 5 AM to write while nursing; teaching students while nursing; reading drafts aloud to Baby while nursing; Baby stopping mid-nursing, smiling up at my voice.

Jones: Two pregnancies and new motherhood. Dying mother-in-law. Aging dog. Car wrecks. “Game of Thrones,” “True Detective,” “The Americans,” “Broad City,” and anything else I could binge-watch while bouncing a fussy baby.

Ng: Book tour; parenting a preschooler; gut-renovating a house while I was still living in it.

Martin: Left LA for Michigan, found some baby bats in the basement, took the bats to a bat sanctuary, ran out of money, made emojis, was eating a lot of pork products actually.

Tallent: Black coffee, campfire coals, sleeping bags filled with windblown sand; dutch oven enchiladas and cheap beer and the company of friends.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Martin: I don’t believe I have experienced this particular feeling.

Jones: “You don’t write like most women.”

Tallent: Once you’ve written a book, its interpretation is out of your hands. That’s why you work like hell writing it. The other stuff, the stuff that is off base, you cannot help that and that is not very much about you.

Ng: Honestly, if anyone reads my work, they’re doing me a favor, so they get to use whatever words they want to describe it. I can’t control that, nor if they like the work, so best not to even try.

Henderson: I am mostly grateful for the words people use to describe my writing, except one I heard from an editor who rejected an essay she called “sweet.” Who the F you calling sweet?

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Ng: A drummer. Or a sculptor.

Henderson: Farmer, bootlegger, midwife.

Martin: Restaurateur.

Jones: FBI profiler.

Tallent: Climate activist or a professional adventure sports photographer. Not a famous one, an unknown one who hangs out drinking beer with athletes who are too homely and too disorganized to ever make it big, but who love the hell out of the sport.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Tallent: I’m a demon coffee drinker, but have lots yet to learn about whiskey and malt beverages, and know even less about typewriters and scarves and coffeehouses, all of which I’m given to understand are lynchpins.

Martin: Good with brevity, bad with giving quiet moments their space.

Jones: I think I have a knack for making backstory interesting, but the flipside is that I always write too much. I wish I had better instincts for what to leave out so that I wouldn’t have to make so many painful cuts when I revise.

Ng: I think I’m good at metaphors and descriptions. Plot doesn’t come naturally to me, so I work really hard at it.

Henderson: I think I’m good at transitions, which are underrated—the connective tissue, the getting from Point A to Point B. I would really like my next book to be funnier. This book has approximately one and a half jokes.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Jones: I guess I don’t contend with it.

Henderson: I want to make another bootlegging joke but I’m not funny enough. The real answer is that I contend freshly with this every day, and that what helps is remembering that other people’s writing matters to me, and that what I’ve written before has mattered, reportedly, to others. Except that lady who called it “sweet.” F her.

Tallent: If you’re talking about the writing, I guess I just wanted to put true things on the page, in case there should ever be someone who might read them and feel less alone. I was never anxious that other people should find it interesting. You don’t write a book for everyone. You write the book for someone who might find solace in its pages, and yeah, it’s true, there is no certainty here, but even that doubtful chance seems worthwhile to me. And all the rest, you let go.

Ng: Well, you asked me for these responses, so . . . In all seriousness, I don’t ever assume people will want to hear what I have to say; I write because I’m trying to figure out what I think. For me, the process of writing is slowly articulating to myself something that’s important to me. If someone else also finds that thought meaningful, then it’s a bonus, but if others don’t find it interesting, that’s okay—not every book is for everyone.

Martin: Great literature is not for everyone.