Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 298

September 17, 2017

Does marijuana affect your sleep?

(Credit: AP Photo/Jeff Chiu, File)

If you speak to someone who has suffered from insomnia at all as an adult, chances are good that person has either tried using marijuana, or cannabis, for sleep or has thought about it.

This is reflected in the many variations of cannabinoid or cannabis-based medicines available to improve sleep — like Nabilone, Dronabinol and Marinol. It’s also a common reason why many cannabis users seek medical marijuana cards.

I am a sleep psychologist who has treated hundreds of patients with insomnia, and it seems to me the success of cannabis as a sleep aid is highly individual. What makes cannabis effective for one person’s sleep and not another’s?

While there are still many questions to be answered, existing research suggests that the effects of cannabis on sleep may depend on many factors, including individual differences, cannabis concentrations and frequency of use.

Cannabis and sleep

Access to cannabis is increasing. As of last November, 28 U.S. states and the District of Columbia had legalized cannabis for medicinal purposes.

Research on the effects of cannabis on sleep in humans has largely been compiled of somewhat inconsistent studies conducted in the 1970s. Researchers seeking to learn how cannabis affects the sleeping brain have studied volunteers in the sleep laboratory and measured sleep stages and sleep continuity. Some studies showed that users’ ability to fall and stay asleep improved. A small number of subjects also had a slight increase in slow wave sleep, the deepest stage of sleep.

However, once nightly cannabis use stops, sleep clearly worsens across the withdrawal period.

Over the past decade, research has focused more on the use of cannabis for medical purposes. Individuals with insomnia tend to use medical cannabis for sleep at a high rate. Up to 65 percent of former cannabis users identified poor sleep as a reason for relapsing. Use for sleep is particularly common in individuals with PTSD and pain.

This research suggests that, while motivation to use cannabis for sleep is high, and might initially be beneficial to sleep, these improvements might wane with chronic use over time.

Does frequency matter?

We were interested in how sleep quality differs between daily cannabis users, occasional users who smoked at least once in the last month and people who don’t smoke at all.

We asked 98 mostly young and healthy male volunteers to answer surveys, keep daily sleep diaries and wear accelerometers for one week. Accelerometers, or actigraphs, measure activity patterns across multiple days. Throughout the study, subjects used cannabis as they typically would.

Our results show that the frequency of use seems to be an important factor as it relates to the effects on sleep. Thirty-nine percent of daily users complained of clinically significant insomnia. Meanwhile, only 10 percent of occasional users had insomnia complaints. There were no differences in sleep complaints between nonusers and nondaily users.

Interestingly, when controlling for the presence of anxiety and depression, the differences disappeared. This suggests that cannabis’s effect on sleep may differ depending on whether you have depression or anxiety. In order words, if you have depression, cannabis may help you sleep — but if you don’t, cannabis may hurt.

Future directions

Cannabis is still a schedule I substance, meaning that the government does not consider cannabis to be medically therapeutic due to lack of research to support its benefits. This creates a barrier to research, as only one university in the country, University of Mississippi, is permitted by the National Institute of Drug Abuse to grow marijuana for research.

New areas for exploration in the field of cannabis research might examine how various cannabis subspecies influence sleep and how this may differ between individuals.

One research group has been exploring cannabis types or cannabinoid concentrations that are preferable depending on one’s sleep disturbance. For example, one strain might relieve insomnia, while another can affect nightmares.

Other studies suggest that medical cannabis users with insomnia tend to prefer higher concentrations of cannabidiol, a nonintoxicating ingredient in cannabis.

This raises an important question. Should the medical community communicate these findings to patients with insomnia who inquire about medical cannabis? Some health professionals may not feel comfortable due to the fluctuating legal status, a lack of confidence in the state of the science or their personal opinions.

At this point, cannabis’s effect on sleep seems highly variable, depending on the person, the timing of use, the cannabis type and concentration, mode of ingestion and other factors. Perhaps the future will yield more fruitful discoveries.

At this point, cannabis’s effect on sleep seems highly variable, depending on the person, the timing of use, the cannabis type and concentration, mode of ingestion and other factors. Perhaps the future will yield more fruitful discoveries.

Deirdre Conroy, Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of Michigan

Trump moves backward on drug sentencing. California progresses

(Credit: Getty/Instants)

The Trump Justice Department under prohibitionist Attorney General Jeff Sessions is reviving some of the drug war’s worst sentencing practices — mandatory minimum sentences, charging low-level defendants with the harshest statutes.

But that doesn’t mean the states have to follow suit. As has been the case with climate change, environmental protection, trade, and the protection of undocumented residents, California is charting its own progressive path in the face of the reactionaries in Washington.

The latest evidence comes from Sacramento, where the state Assembly passed a bill to stop sentencing drug offenders to extra time because they have previous drug convictions. The measure, Senate Bill 180, also known as the Repeal Ineffective Sentencing Enhancements (RISE) Act, passed the state Senate in June and now goes to the desk of Gov. Jerry Brown.

The bill would end a three-year sentence enhancement for prior drug convictions, including petty drug sales and possession of drugs for sales. Under current law, sale of even the tiniest amounts of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine can earn up to five years in prison, and each previous conviction for sales or possession with intent add three more.

State sheriffs complain that the drug sentencing enhancement is the leading cause of 10-year-plus sentences being served in their county jails, which now shoulder more of the burden of housing drug war prisoners after earlier reforms aimed at reducing prison overcrowding shifted them to local lock-ups. As of 2014, there were more than 1,500 people in California jails sentenced to more than five years and the leading cause of these long sentences was non-violent drug sales offenses.

“People are realizing that it is time to reform the criminal justice system so that there’s more emphasis on justice and rehabilitation,” Mitchell said after the final vote on SB 180, which is supported by nearly 200 business, community, legal and public-service groups. “By repealing sentencing enhancements for people who have already served their time, California can instead make greater investments in our communities. Let’s focus on putting ‘justice’ in our criminal-justice system.”

“This sentencing enhancement has been on the books for 35 years and failed to reduce the availability or sales of drugs within our communities,” said Eunisses Hernandez of the Drug Policy Alliance, which supported the bill. “These extreme and punitive polices of the war on drugs break up families and don’t make our communities any safer.”

The bill is part of a set of bills known as the #EquityAndJustice package aimed at reducing inequities in the system. Authored by state Sens. Holly Mitchell, D-Los Angeles, and Ricardo Lara, D-Long Beach, the package also includes Senate Bill 190, which would end unreasonable fees on the families of incarcerated children and also sits on the governor’s desk, as well as Senate Bill 355, which will end the requirement that innocent defendants reimburse the counties for the cost of appointed counsel. Brown has already signed that into law.

“Harsh sentencing laws have condemned a generation of men of color, and with SB 180 and other bills in the Equity and Justice package we are on our way to restoring the values of rehabilitation to the criminal justice system,” Lara said.

When Washington is in the hands of authoritarian, law-and-order politicians like Trump, Sessions and the Republican Congress, it’s time for the states to step up. California is showing how it’s done.

Watch Mitchell and Lara as they began the process of getting it done:

Rethinking the “infrastructure” discussion amid a blitz of hurricanes

Destruction left after Hurricane Irma (Credit: Getty/Gerben Van Es)

The wonky words infrastructure and resilience have circulated widely of late, particularly since Hurricanes Harvey and Irma struck paralyzing, costly blows in two of America’s fastest-growing states.

The wonky words infrastructure and resilience have circulated widely of late, particularly since Hurricanes Harvey and Irma struck paralyzing, costly blows in two of America’s fastest-growing states.

Resilience is a property traditionally defined as the ability to bounce back. A host of engineers and urban planners have long warned this trait is sorely lacking in America’s brittle infrastructure.

Many such experts say the disasters in the sprawling suburban and petro-industrial landscape around Houston and along the crowded coasts of Florida reinforce the urgent idea that resilient infrastructure is needed more than ever, particularly as human-driven climate change helps drive extreme weather.

The challenge in prompting change — broadening the classic definition of “infrastructure,” and investing in initiatives aimed at adapting to a turbulent planet — is heightened by partisan divisions over climate policy and development.

Of course, there’s also the question of money. The country’s infrastructure is ailing already. A national civil engineering group has surveyed the nation’s bridges, roads, dams, transit systems and more and awarded a string of D or D+ grades since 1998. The same group has estimated that the country will be several trillion dollars short of what’s needed to harden and rebuild and modernize our infrastructure over the next decade.

For fresh or underappreciated ideas, ProPublica reached out to a handful of engineers, economists and policy analysts focused on reducing risk on a fast-changing planet.

Alice Hill, who directed resilience policy for the National Security Council in the Obama administration, said the wider debate over cutting climate-warming emissions may have distracted people from promptly pursuing ways to reduce risks and economic and societal costs from natural disasters.

She and several other experts said a first step is getting past the old definition of resilience as bouncing back from a hit, which presumes a community needs simply to recover.

“I don’t think of resilience in the traditional sense, in cutting how long it takes to turn the lights back on,” said Brian Bledsoe, the director of the Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems at the University of Georgia. “Resilience is seizing an opportunity to move into a state of greater adaptability and preparedness — not just going back to the status quo.”

In thinking about improving the country’s infrastructure, and provoking real action, Bledsoe and others say, language matters.

Bledsoe, for instance, is exploring new ways to communicate flood risk in words and maps. His institute is testing replacements for the tired language of 1-in-100 or 1-in-500-year floods. A 100-year flood has a 1 in 4 chance of occurring in the 30-year span of a typical home mortgage, he said, adding that’s the kind of time scale that gets people’s attention.

Visual cues matter, too, he said. On conventional maps, simple lines marking a floodplain boundary often are interpreted as separating safe zones and those at risk, Bledsoe said. But existing models of water flows don’t provide the full range of possible outcomes: “A 50-year rain can produce a 100-year flood if it falls on a watershed that’s already soaked or on snowpack or if it coincides with a storm surge.”

“The bright line on a map is an illusion,” he said, particularly in flat places like Houston, where a slight change in flood waters can result in far more widespread inundation. Risk maps should reflect that uncertainty, and wider threat.

Nicholas Pinter, a University of California, Davis, geoscientist who studies flood risk and water management, said that Florida is well-situated to build more wisely after this disaster because it already has a statewide post-disaster redevelopment plan and requires coastal communities to have their own.

It’s more typical to have short-term recovery plans — for digging out and getting the lights back on, as 20,000 utility workers are scurrying to do right now.

The advantage of having an established protocol for redevelopment, he said, is it trims delays.

“Draw up plans when the skies are blue and pull them off the shelf,” he said of how having rebuilding protocols in place can limit repeating mistakes. “That fast response cuts down on the horrible lag time in which people typically rebuild in place.”

The rebuilt levee wall that was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina, in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, Louisiana (Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

In a warming climate, scientists see increasing potential for epic deluges like the one that swamped Houston and last year’s devastating rains around Baton Rouge, Louisiana. How can the federal government more responsibly manage such environmental threats?

Many people point to the National Flood Insurance Program, which was created to boost financial resilience in flood zones, but has been criticized from just about every political and technical vantage point as too often working to subsidize, instead of mitigate, vulnerability.

As has happened periodically before, pressure is building on Congress to get serious about fixing the program (a reauthorization deadline was just pushed from this month toward the end of the year).

How this debate plays out will have an important impact on infrastructure resilience, said Pinter of the University of California, Davis. If incentives remain skewed in favor of dangerous and sprawling development, he said, that just expands where roads, wires, pipelines and other connecting systems have to be built. “Public infrastructure is there in service of populations,” he said.

He also said the lack of federal guidance has led to deeply uneven enforcement of floodplain building at the state level, with enormous disparities around the country resulting in more resilient states, in essence, subsidizing disaster-prone development in others.

“Why should California, Wyoming or Utah be paying the price for Houston, Mississippi or Alabama failing to enforce the National Flood Insurance Program? ” he said.

Bledsoe, at the University of Georgia, said there’s no need to wait for big changes in the program to start making progress. He said the National Flood Insurance Program has a longstanding division, the Community Rating System, that could swiftly be expanded, cutting both flood risk and budget-breaking payouts. It’s a voluntary program that reduces flood insurance rates for communities that take additional efforts beyond minimum standards to reduce flood damage to insurable property.

Despite the clear benefits, he said, only one municipality, Roseville, California, has achieved the top level of nine rankings and gotten the biggest insurance savings — 45 percent. Tulsa, Oklahoma, Fort Collins, Colorado, King County, Washington, and Pierce County, Washington, are at the second ranking and get a 40 percent rate cut. Hundreds of other municipalities are at much lower levels of preparedness.

“Boosting participation is low-hanging fruit,” Bledsoe said.

Some see signs that the recent blitz of hurricanes is reshaping strategies in the Trump White House. President Donald Trump’s infrastructure agenda, unveiled on August 15, centered on rescinding Obama-era plans to require consideration of flood risk and climate change in any federal spending for infrastructure or housing and the like. The argument was built around limiting perceived red tape.

After the flooding of Houston less than two weeks later, Trump appointees, including Tom Bossert, the president’s homeland security adviser, said a new plan was being developed to insure federal money would not increase flood risks.

On Monday, as Irma weakened over Georgia, Bossert used a White House briefing to offer more hints of an emerging climate resilience policy, while notably avoiding accepting climate change science: “What President Trump is committed to is making sure that federal dollars aren’t used to rebuild things that will be in harm’s way later or that won’t be hardened against the future predictable floods that we see. And that has to do with engineering analysis and changing conditions along eroding shorelines but also in inland water and flood-control projects.”

Robert R.M. Verchick, a Loyola University law professor who worked on climate change adaptation policy at the Environmental Protection Agency under Obama, said federal leadership is essential.

If Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps incorporated future climate conditions, that move would send a ripple effect into real estate and insurance markets, forcing people to pay attention, he said. If the federal government required projected climate conditions to be considered when spending on infrastructure in flood-prone areas, construction practices would change, he added, noting the same pressures would drive chemical plants or other industries to have a wider margin of safety.

“None of these things will change without some form of government intervention. That’s because those who make decisions on the front end (buying property, building bridges) do not bear all the costs when things go wrong on the back end,” he wrote in an email. “And on top of that, human beings tend to discount small but important risks when it seems advantageous in the short-run.”

After a terrible storm, he said, most Americans are willing to cheer a government that helps communities recuperate. But people should also embrace the side of government that establishes rules to avoid risk and make us safer. That’s harder, he said, because such edicts can be perceived by some as impinging on personal freedom.

“But viewed correctly, sensible safeguards are part of freedom, not a retreat from it,” he said. “Freedom is having a home you can return to after the storm. Freedom is having a bridge high enough to get you to the hospital across the river. Freedom is not having your house surrounded by contaminated mud because the berm at the neighboring chemical plant failed overnight.”

Thaddeus R. Miller, an Arizona State University scientist who helps lead a national research network focused on “Urban Resilience to Extreme Events,” said in an email that boosting the capacity of cities to stay safe and prosperous in a turbulent climate requires a culture shift as much as hardening physical systems:

“Fundamentally, we must abandon the idea that there is a specific standard to which we can control nature and instead understand that we are creating complex and increasingly difficult-to-control systems that are part social, part ecological and part technological. These mean not just redesigning the infrastructure, but redesigning institutions and their knowledge systems.”

After the destruction and disruption from Hurricane Sandy, New York City didn’t just upgrade its power substations and subway entrances, Miller said in a subsequent phone call. The city also rebooted its agencies’ protocols and even job descriptions. “Every time a maintenance crew opens a sewer cover, fixes or installs a pipe, whether new or retrofitting, you’re thinking how to enhance its resilience,” Miller said.

Miller said another key to progress, particularly when federal action is limited or stalled, is cooperation between cities or regions. Heat was not an issue in Oregon historically, Miller said, but it’s becoming one. The light rail system around Portland was designed to work with a few 90-degree days a year, he said. “The last couple of summers have seen 20-plus 90-degree days,” he said, causing copper wires carrying power for the trains to sag and steel rails to expand in ways that have disrupted train schedules. Similar rail systems in the Southwest deal with such heat routinely, said Miller, who has worked in both regions. The more crosstalk, the better the outcome, he said.

“At the broadest level, we need to think about risks and how infrastructure is built to withstand them at a landscape level,” Miller added. “We can longer commit to evaluating the impacts and risks of a single project in isolation against a retrospective, stationary understanding of risk (e.g., the 100-year flood we’ve been hearing so much about.)”

He said that an emerging alternative, “safe-to-fail” design, is more suited to situations where factors contributing to extreme floods or other storm impacts can’t be fully anticipated. “Safe-to-fail infrastructure might allow flooding, but in ways that are designed for,” he said.

(With an Arizona State colleague, Mikhail Chester, Miller offered more details in a commentary published last week by The Conversation website, laying out “six rules for rebuilding infrastructure in an era of ‘unprecedented’ weather events.”)

Deborah Brosnan, an environmental and disaster risk consultant, said the challenge in making a shift to integrating changing risks into planning and investments is enormous, even when a community has a devastating shock such as a hurricane or flood or both:

“It requires a radical shift in how we incorporate variability in our planning and regulations,” she said. “This can and will be politically difficult. New regulations like California fire and earthquake codes and Florida’s building codes are typically enacted after an event, and from a reactive ‘make sure this doesn’t happen again’ perspective. The past event creates a ‘standard’ against which to regulate. Regulations and codes require a standard that can be upheld, otherwise decisions can be arbitrary and capricious. For climate change, non-stationarity would involve creating regulations that take account of many different factors and where variability has to be included. Variability (uncertainy) is the big challenge for these kinds of approaches.”

Stephane Hallegatte, the lead economist at the Word Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, has written or co-written a host of reports on strategies for limiting impacts of climate change and disasters, particularly on the poor. When asked in an email exchange what success would look like, he said the World Bank, in various recent reports, has stressed the importance of managing disaster risks along two tracks: both designing and investing to limit the most frequent hard knocks and then making sure the tools and services are available to help communities recover when a worst-case disaster strikes.

He added: “Facing a problem, people tend to do one thing to manage it, and then forget about it. (‘I face floods; I build a dike; I’m safe.’) We are trying to work against this, by having risk prevention and contingent planning done together.”

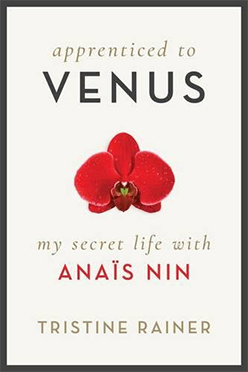

My mentor, Anaïs Nin

Anaïs Nin (Credit: Wikimedia)

The 1966 publication of “The Diary of Anaïs Nin” (1931-1934) was perfectly in sync with the zeitgeist. Thanks to Anaïs having edited out any mention of Hugo, her diary was perceived as the true record of an openly sexual single woman living on her own in Paris with no need of a husband. I knew Anaïs’s liberated, independent lifestyle was invented, but that didn’t stop me from trying to replicate it along with the young women of the ’60s who took it as fact.

The first published volume of Anaïs’s Diary created a new persona for her—not Anaïs Guiler, the privileged wife of an investment banker, nor Anaïs Pole, the bohemian wife of a sexy younger man, but Anaïs Nin, the independent, unmarried woman who had lovers and wrote about them. She positioned herself as a single woman ahead of her time who championed a woman’s right to explore and value her own sexuality. For my generation of early Boomers, Anaïs Nin became the icon for our sexual liberation. Colleges and universities all over the country invited her to speak, accept awards, and attend celebrations in her honor.

Anaïs almost always said yes. I had thought she would limit her public exposure given the risks, but she leapt to it with the same abandon and repertoire of tricks that had kept her aloft on her illegal trapeze for over a decade. Radio interviews, TV appearances, auditoriums full of adoring fans—Anaïs appeared before them all as a joyful, free, compassionate, wise, and accomplished exemplar of the new woman. She wasn’t about to let fear of exposure prevent her from reaping the rewards of a literary renown that had so long eluded her.

Thanks to academic feminists, such as I soon became, and our promotion of previously ignored women authors, Anaïs gained a genuine self-confidence she had lacked. She was finally, and within her lifetime, recognized for what she had intuitively known from childhood: that she was the foremost diarist of the twentieth century. Her belated success proved to her that she had been right in sticking to the callings of her heart and soul, reaffirming her faith in women’s intuition and subjectivity; while I, at the same time, was being trained in grad school to accept only supportable, documented objectivity.

Despite the many accusations from critics that a woman who published her diary had to be a narcissist, Anaïs, unlike most people who achieve fame, proved a better person for it. She became more centered, generous, and kind—and happier because she didn’t have to lie to her husbands as much. She now had money from her royalties to pay for her coast-to-coast flights, as well as a lecture agent who booked appearances for her alternately on either coast. What a relief for her to have this help with the trapeze!

It was glorious to see Anaïs in these days of her fulfillment. Hugo made few demands on her because he was now completely dependent on her financially, while Rupert leapt to play the handsome young consort to her elegant priestess. She kept her friends “in the know” close, holding Chablis-and-cheese parties for us at the Silver Lake house.

Anaïs would still panic when one or the other husband overheard something incriminating, and although I remained as tightlipped as a CIA agent, every time I traveled east to visit my godmother, Anaïs would phone to ban me from speaking about her to Lenore or seeing Hugo. After my failure to prevent Rupert’s middle-of-the-night phone call to Hugo years before, she never again entrusted me to guard her trapeze, which was fine with me as long as I remained her confidante. The responsibility of collecting Hugo’s mail and intercepting his calls fell to a ditzy pair of middle-aged women—“the twins”—friends of Renate who dressed alike and accepted little cash gifts for their services.

I now had a different function in Anaïs’s life. Since I was getting my PhD in English literature at UCLA, my new assignment was to legitimize her published Diaries and novels within the university, for while the coeds of America celebrated her, the academic establishment still held her in contempt. Anaïs knew that her lasting literary reputation depended upon young feminist scholars, such as myself, teaching and writing about her work. I reveled in my reflected glory as Anaïs’s protégée and would have liked to tell everyone. However, Renate advised me to downplay the personal relationship, so I’d receive fewer difficult-to-answer questions and would be taken more seriously as an Anaïs Nin scholar.

I’d gone to UCLA for grad school because it would keep me near Anaïs, and there I joined one of the earliest women’s consciousness-raising groups. Initially, my involvement with the group increased my admiration for Anaïs. Our method for raising our consciousness echoed the nonjudgmental intimacy of her Diaries. At our meetings, we went around in a circle sharing our personal experiences on a particular theme: mothers, fathers, siblings, lovers, to have or not to have children, professions closed to us, the many putdowns for being female we’d internalized.

We confided to each other our secrets, trusting that anything said within the group would never leave it: a baby given up for adoption, years of spousal abuse, faked orgasms, an abortion, a sexual attraction to another woman, an unrevealed rape. Like snakes, our stories dropped into the pit encircled by our chairs, and we examined them wriggling there along with our shame and guilt. We murmured to each other, “It’s not your fault . . . That’s why we are meeting, so that someday it will be different for women.”

By 1970, though, we had transformed into an action group with the goal of establishing a Women’s Studies program at UCLA. Those of us who were grad students put together proposals for classes we believed should be offered to undergraduate women, and our whole group, including faculty wives, university secretaries, and women from the community, pressured the administration to fund the courses. By August 1971, a number of us grad students were scheduled to teach the very first classes at UCLA that acknowledged the contributions of women in our respective fields.

By that time, Anaïs had edited and published three volumes of her Diary. I made the first two volumes, then in paperback, required reading for my Identity through Expression: Women Writers class, offered through the English department. When I handed out a draft of my syllabus to my women’s consciousness circle for feedback, Clara, the most brilliant and beautiful of our remarkably attractive group, objected.

“I guess you could include Nin for historical reasons, but you can’t call her a feminist author as you have it here.” Clara snapped her unpainted fingernails against my course outline and pushed back a cluster of copper curls that haloed her flawless face.

With her continental sophistication acquired from having attended the Sorbonne and her impeccably correct leftist politics, Clara awed me as Anaïs once had. It bothered me that when I’d first let drop to Clara that I knew Anaïs Nin, she had been unimpressed, unlike everyone else who marveled that the exotic diarist was living, no longer in Paris, but right there in prosaic LA.

The heavyset provost’s secretary asked, “Who’s Annis Nin?”

Clara gestured for me to answer, but I nodded back, wanting to hear her take on Anaïs. Clara began, probably borrowing from her prepared class on French women writers: “The French like Nin because they have a tradition for her. She follows in a direct line from the French courtesans who were better known for their lovers and literary salons than their own writing. They were professional muses: Marion Delorme, Claudine-Alexandrine Guerin de Tencin, Marie Duplessis, Ninon de l’Enclos.” Clara deferentially flipped a hand to emphasize her ease with these French names. “They were like the Greek hetaera or the Japanese geishas,” she continued, “experts in the arts of pleasing men. They were oppressed because they could only survive by maintaining the pleasure of their male patrons. They could hold power only as long as their sexual appeal lasted, though some of them were able to make it last well into old age thanks to their beauty tricks.”

“Do you know any of those tricks?” the provost’s secretary asked.

“They were stupid. They used white powder that gave them lead poisoning.” Clara waved away the question. “That’s not the point. The point is they were hardly liberated.”

“Well, they were for their time,” I argued.

Clara took my opinion seriously. “I suppose you could say that. By being parasites on the nobility they had better lives than servant women or farmer’s wives, but that was a question of class.”

I enjoyed batting ideas with Clara; she always came back with a well-reasoned argument, an intellectual muscularity absent in the feminine subjectivity and intuition Anaïs heralded. I countered to Clara, “In some ways the courtesans were better off than we are. They had the leisure to write. Their time wasn’t taken up having children, or working, or managing households.”

I realized immediately that Clara would see “leisure to write” as an elitist concern, but the provost’s secretary jumped in: “Sounds like a liberated life to me!”

Clara gave her a withering look. “A muse spends her life enabling men’s creativity instead of her own.”

“Well, Anaïs Nin isn’t just a muse.” I came to my mentor’s defense. “She’s a diarist and novelist in her own right. Maybe she was a muse to Henry Miller when they were in Paris, but now she’s committed to her own work.”

Even as I was saying it, though, I realized it wasn’t true. Anaïs had completely abandoned her diary and novel writing, in favor of playing muse to her fans through her prolific correspondence. Clara was right, as well, that Anaïs was like a courtesan in that everything about her was delicate and feminine—her soft voice, her graceful movements, her painstaking appearance—as if she’d been designed to fulfill men’s fantasies.

Clara smirked at my defense of Anaïs. “Oh, that’s right, you know her, don’t you?”

“A little.”

“You know her?” the provost’s secretary interrupted. “Can you get her to visit our group?”

“I don’t think so. She has a lecture agent who books all her appearances.”

“Offer the stipend you get for guest lecturers in your class, and we’ll all come,” the excited secretary urged.

Her unabashed eagerness made me want to show Anaïs off to the group, but Clara said, “She’s not going to come to your undergraduate class or visit our little group. It would insult her narcissism now that she’s a star.”

I was so tired of hearing this accusation of narcissism against Anaïs that I was determined to show Clara she was wrong. I’d get Anaïs to come talk to our group and my class. It would be a feather in my cap, and Clara would see for herself how egalitarian, witty, eloquent—and feminist—Anaïs really was.

I always seemed to be trying to prove something to Clara because compared to her raised political consciousness, mine always came up short. She participated in a dangerous underground for Latin American victims of terror, summered on sugar collectives in Cuba, and stood in solidarity with working class women. So in addition to the UCLA women’s group, I joined an on-campus socialist group for grad students and professors. It turned out, though, that our group didn’t actually do anything except read and discuss texts by Marx, Lenin, and Engels. One evening, I said to the study group—because my landlord wasn’t renewing my lease—“What if, instead of just talking about communism, we tested it ourselves to see if we could make it work?”

“What do you mean?” asked Bob, whose beard was the same orange shade as his long hair. He liked experiments; he had a PhD in nuclear physics and had told us that the only jobs he could find in his field were for the US government, so he’d saved his large salary for three years and dropped out at twenty-six with enough money, according to his calculations, to last the rest of his life.

I proposed, “What if we become a commune and live together in a house where we each pay according to our ability and receive according to our need?” I didn’t think anyone would go for the idea, especially since my income as a teaching assistant was near bottom, but to my amazement three of the guys said yes. Bob brought along his girlfriend, so we were five; sufficient, we decided, to call ourselves a commune. After we added up what we could collectively pay for rent, we began to look for a mansion to lease.

We found a Greene and Greene–style manor house in Santa Monica four blocks from the boardwalk. In August we all moved in, the guys unloading salvaged furniture my mother had been happy to clear from her living room and running my mattress up the curved, balustraded stairway. We joined a Venice food co-op for weekly boxes of organic produce and established a nightly ritual of communal dinners in our chandeliered dining room.

I knew that upon Anaïs’s return from a European trip, she would want to see my commune. She was avid about keeping up with the alternative culture scene: she’d tramped through a field to see geodesic domes, attended love-ins and sit-ins, and turned me on to Judy Chicago’s feminist art installations.

So as I was driving to Silver Lake, I formulated my plan. I’d invite her to the commune for a collectively prepared dinner, and afterwards in our expansive living room, she could address my women’s group and class. I’d prove to Clara that Anaïs didn’t consider our group small potatoes. I’d offer Anaïs my course speaker stipend, because I knew she would appreciate the resonance that I was proffering her a real invitation, with a real stipend, for a real university event, whereas my apprenticeship had begun seven years earlier by sending a fictitious invitation, with a fictitious stipend, for a nonexistent university event. That’s the way it was with Anaïs. Whatever she imagined—her mariage a trois, her literary stardom, her financial independence—eventually actualized. She had taught me to dream and to actualize my dreams as she had.

When I entered the open front door, Anaïs and Renate were huddled on the built-in couch, discussing their facelift experiences. They changed the subject, knowing that as a doctrinaire feminist now, I considered plastic surgery to hide a woman’s age politically incorrect.

After I’d kissed their lifted cheeks, they insisted on hearing all about my new Women’s Lit class. It was the first time anyone had taught Anaïs’s Diaries in a university. Anaïs wanted to know the other authors on my syllabus, but when I listed Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, Maya Angelou, Sylvia Plath, and Nikki Giovanni, she wrinkled her nose in distaste while nodding discreetly.

I described the first meeting of my class, when eager young women had lined up in the hallway and poured out into the courtyard, hoping to get on the waiting list. “They limited the enrollment to thirty-two, and over a hundred women showed up!” I enthused. “One guy pushed his way into the classroom and shouted, ‘This is sexism! I should be able to take this class!’”

“What did you say?” Renate was enjoying this.

“I told him, ‘This class is for women only. There are plenty of classes you can take that were designed just for men.’”

“Did he leave?” Renate asked.

“No! He threatened to sue me and the university for discrimination against him for being the wrong gender!”

Renate exclaimed, “Oh, no, Tristine!” After her ordeal of being sued and losing her house to her contractor, Renate was terrified of lawsuits.

“That kid won’t sue me,” I assured Renate. “I told him he could get in line with the women in the hallway and sign up on the waiting list. I said, ‘I promise you, you’ll have as much of a chance of getting in the class as they do, so you are being treated equally.’”

“That was good.” Anaïs smiled. She didn’t approve of men being seen as the enemy. She repeatedly reminded me that a woman should be responsible for her own emotional issues and not put them on the man.

I shared with Anaïs and Renate my mother’s reaction when I’d told her about my consciousness group’s victory in getting funding for our classes.

“That’s wonderful, Trissy!” Mother’s heavily jowled face, exhausted from overwork, had lifted with a rare smile of hope and pride. It was the same with Renate and Anaïs. Their faces were already lifted, and they were already full of hope because of the success of Anaïs’s Diaries; but they glowed, too, with pride for what we younger women had accomplished.

This gave me my opening. I invited Anaïs to address my class and women’s group.

“Don’t you dare, Anaïs!” Renate butted in. “You have to preserve your strength.”

Damn, Renate was working at a cross-purpose. I should have talked to her beforehand.

I moaned to Anaïs, “Oh, my students will be so disappointed if you don’t come!”

Anaïs looked stricken at the thought of disappointing them. She routinely accepted speaking engagements at remote Midwestern colleges where she had to sleep in associate professors’ guestrooms, and she personally answered every letter she received in sack loads because, she said, “I don’t want my readers to feel rejected. I know what that feels like.”

True, she loved the rock star reception when she entered an overflowing auditorium, but in fairness she loved her admirers back. She invited to her parties at the Silver Lake house the loneliest souls met on her travels, people who had told her their sob stories in their letters and then stalked her for, in their floaty words, “a touch of her magic.” She felt it was her job to save them, so Renate and I would find ourselves having to socialize with these airheaded young people—the painfully shy poet who would only speak if asked a question, the girl disfigured in a riding accident who kept one side of her face angled away from you, the runaway with the bad teeth, and the recently released ex-con—all sipping Chablis while standing next to Bebe Barron, a pioneer of electronic music; or James Herlihy, whose novel Midnight Cowboy had become an Academy Award–winning movie.

Anaïs would glide over to talk to the most awkward and shy guest at the party and shame the rest of us into following her example. She described herself accurately when she wrote that out of her father calling her ugly as a child had come her x-ray vision. People were made of crystal for her. She saw right through their defects—the humped back, the duck walk, the embarrassing acne—straight to their essence, the shadow of their disappointments, the outline of their desires, the glow of their dreams. She completely lacked snobbery and practiced an almost saintly kindness.

I’d seen photos of her male psychiatrists Rene Allende and Otto Rank, both of whom she’d told me she’d slept with to “help return them to their bodies.” The thought of Anaïs giving charity sex to these aggressively ugly men revolted me. Yet, as they had, I was now playing on her saintly impulses to get what I wanted, and Renate knew exactly what I was doing.

“How can your students be disappointed?” Renate chided me. “Did you promise them Anaïs’s appearance without even asking her?”

I thought Anaïs would object, “Oh, I enjoy the appearances. They energize me,” as she always did when Renate tried to get her to slow down. Instead, she sighed, “I am getting tired of repeating myself. And I’m beginning to feel, I don’t know, insincere.” This was something new!

In response to Renate’s and my double-take, Anaïs explained, “I say I value intimacy, but the crowds of people are the opposite of intimate. I don’t think all this celebrity is good for me.”

“Now you see the horror of fame,” Renate said with satisfaction.

“It’s not that bad, Renate.” Anaïs’s laugh was a tiny cough. “Besides, this would be for Tristine.” She smiled on me. “And it’s not like I have to get on a plane.”

“And it will be intimate,” I promised. “It’ll only be the fourteen women from my consciousness group, my thirty students, and my five commune members.”

“You moved into the commune, Tristine?” Anaïs exclaimed.

“We found a mansion in Santa Monica. We have an acre of grounds and a big rolling lawn in front.”

“I’ve visited communes.” Renate wrinkled her aristocratic nose. “I don’t object to the polymorphously perverse sex, but the houses are so unkempt.”

“Not ours. We have the cleanest, most anally retentive commune ever.”

Anaïs laughed, but Renate harrumphed. “Well, that doesn’t sound like the Birkenstock communes I’ve seen. What about Jadu?” Renate was always concerned about my cat. She’d identified him as my “familiar.”

“He’s the house mascot,” I said.

“I assume you play musical beds.” Renate raised a penciled eyebrow.

“No! I told you, Renate, it’s a socio-political experiment.”

Anaïs coaxed, “Come now. You can’t tell us that there isn’t at least one man in this commune you find desirable.”

After Neal’s disappearance, Sabina had returned to me, and now my varied sex life provided entertainment for our little cabal.

“Give us the latest installment in the Adventures of Donna Juana,” Anaïs commanded gaily.

“Donna Juana has found a Don Juan,” I began.

“That sounds promising!” Anaïs sang. “What’s his name?”

“Don.”

“No, his real name.”

“Don Brannon. The problem is he’s my brother.”

“No, Tristine!” Anaïs cried.

“I thought you were an only child.” Renate scowled.

“I told you before, I have a younger sister and a half-brother.” I was concerned about Renate; she was struggling financially, doing temp work assisting old people, and I was afraid the stress was affecting her usually impeccable memory.

“Oh! Don is just your half-brother,” Anaïs exclaimed. “That’s not so bad.”

“No, Don isn’t actually related to me at all. He’s one of my brothers in the commune.”

“You call them brothers?” Renate said. “Why?”

“Because we live together like a family, and Don says that because we’re brother and sister in the commune it would be like incest if we slept together.”

Renate flipped her hand provocatively. “I don’t see how he can resist the convenience. He wouldn’t have to get in his car and drive, and you’d both get to sleep in your own beds.”

“Oh, Renate!” Anaïs scolded.

“I’m serious,” Renate insisted. “My perfect lover is one I could lower on cables to my bed from the ceiling when I want. When we’re finished doing it, I’d just press a lever and he’d disappear through a trap door into the rafters.”

I chuckled, but Anaïs rolled her eyes. She’d warned me privately that Renate had let herself become bitter about men, and I should avoid her example. “Bitterness makes you prematurely old,” Anaïs frequently declared. “The secret to my eternal youthfulness is that I forbid myself bitterness.”

“What does your Don look like?” Renate wanted to know.

“Like Robert Redford. He runs the Writing Center at UCLA.”

“That’s the kind of man you should be with,” Anaïs said. “Someone who shares your interests in literature. But are you sure he isn’t gay?”

“I’m sure. He has different girlfriends spend the night on weekends. Really beautiful ones.”

“Don’t give up on him then,” Anaïs urged. “When Donna Juana and Don Juan come together it creates a lot of fireworks.” She described her affair with a Don Juan who was an opera singer. “The thing to remember with a Don Juan is that he loses interest the moment you stop being elusive. You have to sustain the cat and mouse game.”

I felt fortunate to have Anaïs as advisor to my love life. There wasn’t a romantic liaison with which she didn’t have personal experience. I was aware that she took vicarious enjoyment through my Sabina adventures, but it seemed only fair given how I, and thousands of other women, had enjoyed her erotic adventures in her novels and Diaries.

Anaïs, Renate, and I often took turns telling tales of our Sabina seductions. As in all our conversations, we looked for the metaphors and myths embedded in our encounters. I learned to include poetic details as Anaïs did and humorous twists as Renate did.

When Anaïs and I would have a private tête-à-tête to seriously discuss my search for the one man who would end my search as Rupert had ended hers, she listened with the concentration of a piano tuner. We compared my raunchy affair with an impoverished writer to hers with Henry Miller, my passion for a handsome poet/revolutionary to hers for Gonzolo, and my seduction of a young, gay film director to her attempts with Gore Vidal. These mirror encounters were not really about the men; they were about Anaïs and me, our game of twinship. They were about watching and being watched, the diarist’s obsessions.

Now she gave me specific recommendations to seduce Don, offering before I left, “I’ll just have to visit and warm him up for you.” So a date was set for her to have dinner at the Georgina Avenue commune and afterwards address my class and women’s group.

The morning of the event, she called to say she’d have to postpone dinner for another time, but she would be there at seven for the talk. I had warned my commune members, my class, and my women’s group not to tell anyone else about Anaïs’s visit or it would get out of hand.

“I promised her an intimate evening, a furrawn.” I used the odd Welsh word Anaïs was then trying to popularize, my mouth gaping as for the dentist.

“Furrawn,” she would say at her lectures, avoiding a yawning fish face by rolling the r and taking “awwn” in the back of her throat. “It means intimate conversation that leads to deep connection. We don’t have a word for it in English, or in French for that matter”—she’d give her guttural half-laugh—“so we have to borrow furrawn from the Welsh.” Privately she’d added to me, referring to her husbands, both of Welsh heritage, “It’s all the Welsh have: a useful word and good-looking men.” Her humor, what she had of it, was so dry that it evaporated before most people got it; but I knew to chuckle because her desiccated jokes were always indicated by her little cough-like laugh.

At 6:00 people started arriving. Our commune’s spacious living room looked like an anthill, teaming with longhaired guys and braless young women in tight T-shirts, most of them crashers. The chairs I’d arranged in a large circle were insufficient and people sat lotus-style on the floor and sprawled on the stairwell, overflowing into the dining room, kitchen, and pantry. The whole thing felt like a huge, unruly surprise party.

I hoped Anaïs wouldn’t be too surprised when she walked in and saw what had happened to the intimate furrawn I’d promised her.

When at 7:00 she had yet to arrive, I became concerned. Anaïs was always punctual. I saw Don standing under the wide arch to our dining room, looking more like Robert Redford than ever with the Sundance Kid mustache he’d recently grown. His arm was around a pretty brunette he’d invited. I was annoyed that he hadn’t asked me if he could bring her, but then, the house was full of crashers who hadn’t asked. They were becoming loud and disorderly. I tried to quiet them by lecturing about Anaïs’s work, but they lapsed into side discussions, too excited to pay attention.

They fell silent, though, when we saw through the front windows the Thunderbird double park on the street, and a cloaked, regal woman stride alone up the inclined path to the porch.

Anaïs was making an entrance for me! She swept through the open front door and, loosening the tie of her black cape, let it fall into red-bearded Bob’s outstretched arms. I’d thought that Bob, as a nuclear scientist, would have been immune to Anaïs’s charm, but he blushed through his freckles and later marveled, “It was like the appearance of a white witch in a Disney film. You could almost see a trail of sparkling fairy dust in her wake!”

Sticking to the evening I’d planned, I ignored the crashers and said, “Before I give the floor to Anaïs, I’d like to introduce my fellow commune members, who are our hosts tonight.” They each stepped forward as I said their names. Anaïs looked directly into Don’s blue eyes when she said, “Thank you so much for allowing me to visit your beautiful home.” I could tell he was smitten.

I then introduced my students, who shot up their hands. “And what about the women in your consciousness group, Tristine?” Anaïs said. “I’ve wanted to meet them for so long.”

The women in my group half-raised their hands, including Clara, whom I’d wanted to impress by delivering Anaïs. Anaïs bowed her head in tribute to them. “You are to be honored for transforming the world by first transforming yourselves. The Women’s Movement has been an example of what I have always advocated, proceeding from the dream outward.” She quoted herself from the Diary: “‘The personal life deeply lived always expands into truths beyond itself.’”

Then she ardently addressed the entire audience, making each person there feel as if she or he had the most intimate connection with her of all. She presented the persona they had come to see: the sensual, independent, liberated woman she’d invented in editing her Diary. She embodied the myth that her readers had embraced as a goddess of love, intimacy, kindness, generosity, romantic idealism, surrealist imagination, and sexual abandon. I saw her that night in all her glory as the consummate woman artist: a practitioner of performance art before it had a name, a visionary of life itself as imaginative theater. I had seen packed auditoriums in a frenzy of adoration, and with this smaller group she likewise played her artist/goddess role to the hilt, quoting herself in her French lullaby rhythm, dropping the names of political friends such as Eugene McCarthy and literary associates such as Rebecca West and Lawrence Durrell, encouraging the women before her to value their individuality, throw off their inheritance of guilt, and live their dreams as she had!

My students eagerly asked questions about her diary writing, which she answered with practiced phrases: “I write to taste life twice,” and “It is a thousand years of womanhood I am recording, a thousand women.”

Some of the young women from my class made passionate personal testimonials to the liberating impact of having read her Diary. One twenty-year-old proclaimed, “You are the mother of us all!” Everyone present looked dazzled, as if they had been touched in a tent revival and received a genuine miracle.

Everyone except Clara, that is. She’d been leaning against the wall distancing herself from my students. Now Clara came forward, flipping a hand upward for Anaïs to spot her. Seeing how beautiful Clara was with her corona of fiery curls, Anaïs offered her most appreciative smile, but Clara did not return it.

She said, “At the end of the second volume of your Diary, you tell us you left Paris because your husband was recalled to the US. But until then there was no mention of you having had a husband. Why is that?”

“My publisher—” Anaïs began, but Clara interrupted her.

“Nowhere do you tell us how you got money for your free life. Yet economic self-sufficiency is the first requirement for woman’s freedom, wouldn’t you agree?”

Anaïs straightened to her full 5’5” height. Her singsong French accent became more pronounced when she answered, “Economic self-sufficiency is essential for woman, but it is not the only ingredient necessary for her freedom. Americans, in particular, are oppressed by the punishing assumptions of Puritanism.” She looked into receptive faces as she spoke, settling on Don’s. “America’s sexual Puritanism must also be examined and dispensed with.” There was a murmur of assent in the room.

“But you haven’t addressed the question left unanswered in your Diaries.” Clara brought Anaïs’s attention back. “How did you make a living? Certainly it wasn’t from your writing. All you published in those years was a booklet of nonprofessional literary criticism on D. H. Lawrence. Not exactly a moneymaker.” There were a few titters from Clara’s supporters. She pressed, “Since it was your marriage to an international banker that made your free, privileged life possible, don’t you think you’re obliged to tell us that? It’s not fair to let women think that they can have a life like yours without a rich, permissive husband like yours.”

There was a hush in the room, stunned fear for Anaïs as the naked emperor exposed by an insurgent. I could not believe what I was witnessing. Clara and Anaïs were playing out a battle that had been raging inside me: Clara on the left, whom I so admired, brave and honest, who challenged unfairness and hypocrisy wherever she found it. Anaïs on the other side, brave and dishonest, my mentor, whom I loved.

Anaïs remained unflappable in the face of Clara’s accusation of deception. “I have given you so much of myself in the Diary,” she intoned sorrowfully. “No woman has revealed so much. I have given voice to the secrets that most women hide. Why do you demand more of me?”

You could feel the audience, like an armada, slowly turn, guns swiveling towards Clara. She shrugged, as if to say, What can I do if you Americans, unlike the French, cannot appreciate a good intellectual row? She shot back at Anaïs, “The question is why you did not ask more of yourself. You intentionally misled your readers into thinking you were self-supporting. All that time you were being supported by Hugo Guiler, a banker!”

Anaïs answered calmly, “Yes, that is why I added at the end of Diary II that the bank recalled my husband to America and we had to leave Paris. That much had appeared in the newspaper; it was public record. That is all I could include about my husband because I did not have his permission to portray him.”

I knew this wasn’t exactly true. It sounded convincing, but not to Clara. She glared at Anaïs accusingly. “You mean that you, the renowned seductress, couldn’t get permission from your own husband, the one you still live with in New York?”

How did Clara know about Hugo in New York? I’d certainly never said anything about him to her. But Anaïs would believe I had!

I could tell Anaïs was furious because her voice became soft and controlled. She demanded of Clara, “Who are you?”

“I’m a member of Tristine’s consciousness group.”

God, Clara was making it sound like I was in on this! Don looked over at me, an eyebrow raised.

Anaïs stood tall and her gemstone eyes bored into Clara. “Where did you get the false impression that I am still married to Hugo?”

Clara said, “Mon Dieu, everyone in Paris knows about you and your double life! Hugo still has friends there, you know.”

Anaïs’s panicked eyes darted to me and back to Clara. “I have no idea what you are talking about,” she said coolly.

I glanced around and, to my horror, saw Rupert stationed on the front porch, standing in the cold by the open door. He must have heard Clara say that Anaïs had a double life and still lived with Hugo! Yet his countenance remained blank. An actor playing possum?

I jumped up. “It’s getting late, and we don’t want to exhaust Anaïs when she’s been so generous to meet with us.”

There were groans and thirty hands shot up. Anaïs recognized only Don. I felt a charge between them before he asked, “Were you the model for Ida Verlaine in Henry Miller’s Sexus?”

“You’d better ask Henry that question.” She laughed gaily, turning away to scan the room for Rupert. “Ah! I see my escort is here! I’m so sorry I cannot stay longer.”

The crowd parted before her as she moved through them to the front door, squeezing proffered hands and returning eager gazes with her radiant, reassuring smile. I tried to catch her eye but couldn’t. Bob rushed up with her cape, and she wrapped it around her before sweeping away.

She did not take Rupert’s arm as they strode to the T-Bird parked up the street. That night, no one could have guessed they were married, the way she kept her distance.

September 16, 2017

How bad could things get?

(Credit: AP)

“This country is going so far to the right you’re not going to recognize it.” Those memorable words were uttered by Richard Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, who proved to be off by almost 50 years. But he and other Nixon cronies, however premature in their timetables, were establishing precedents for today’s worst case scenarios. We have to ask: Which elements of the state-sponsored violence of the ’60s and early ’70s are ready for revival and renewal? What new wrinkles in constitutional crisis might be in the works? Just how far to the right — or the left — will we go?

On taking office in 1969, Mitchell had declared that he was “first and foremost a law-enforcement officer.” The extent of the law-breaking — including murders — that that he and his cronies supervised against radicals, black militants and Democrats, is still coming to light. We have known for decades that the FBI informant drugged the Black Panther Chicago leader Fred Hampton, in December 1969, so that he was helpless to resist when two Chicago cops shot him in the head, in his bed, in the middle of the night. We know of a host of dirty tricks the Bureau deployed to deepen paranoia and internecine warfare in the Black Panther Party, in the New Left and the women’s movement.

Moreover, only recently has it been established, thanks to the research of the historian Arthur M. Eckstein, that in September 1970, high officials of the FBI proposed to Director J. Edgar Hoover that in case of “a state of national emergency” internment camps should be opened — or rather, reopened, for these were the same camps that between 1942 and 1946 held almost 120,000 Japanese-American citizens. This time, they would house 11,000 radicals — what the FBI called “the Security Index.” (I was one.) Habeas corpus would have been abolished. But the FBI was reluctant to commit. In an early appearance of Steve Bannon’s “administrative state” — the one he thinks must be “deconstructed” — many among the 9,000 FBI agents of 1970 preferred fighting crime to keeping tabs on domestic radicals who had committed no crimes.

As the FBI dragged its feet, they didn’t know — no one did — that the state of emergency was a hair’s-breadth from activation. On March 6, 1970, the Weather Underground readied three explosions to “bring the war home” — to America. One exploded prematurely in a townhouse on West 11th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village, killing three of the bombers themselves; the plan had been to detonate it at a dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Two other bombs were set to go off in Detroit — one inside a police station, the other outside a police social club. Both were exposed by an FBI informant. The second one was barely diffused in time. Had all three terror attacks gone off as planned, more than a hundred people would likely have been killed. In the full-blown panic that would have ensued, almost certainly President Nixon would have declared a state of emergency. Chance intervened. The emergency wasn’t declared.

It was also good luck that, two years later, a keen-eyed security guard in the Watergate Hotel discovered duct tape that prevented the locking of a door to the Democratic National Committee office. Police arrested five burglars, who were installing wiretaps. A dogged federal judge, John Sirica, himself a Republican appointee, established that these men were White House employees. The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein established that they were being paid through a Republican slush fund. Good luck doesn’t prevail if institutions don’t work.

How the country was kept from “going so far to the right you’re not going to recognize it” during the Nixon years was partly a matter of luck and partly the triumph of three institutions: the courts, the press and Congress, which launched the proceedings that resulted in President Nixon’s resignation. Nixon, like Trump today, confronted a resistance, and that resistance moved Congress to stand up for the Constitution.

Four years later, Mitchell was convicted of conspiracy, including the inept break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in 1972, obstruction of justice and perjury, for which he served 19 months in prison.

How do we stack up today? Two of the three protective institutions of this battered democracy are standing up to obstruct the depredations of the Trump regime: the courts and the press — the part that Trump calls “the enemy of the people.” Whether Congress will hold its own remains to be seen. The midterm elections next year are up for grabs; signs point in both directions. But America’s narrow escape was not a foregone conclusion during the Nixon years. Nor is it today.

For all the auspicious signs, it’s by no means clear that today’s resistance will successfully withstand the tyrannical forces that are preparing to round up hundreds of thousands, or millions, of immigrants — the forces that offer free Army surplus tanks and bayonets to local police departments; that encourage and placate and pander to white supremacists, some of whom march with semiautomatic rifles and lit torches, and others of whom include an Arizona sheriff found guilty, by a federal judge, of criminal contempt of court for terrorizing brown-skinned people and interning them for months on end in what he unabashedly called “a concentration camp.”

Will the energies of resistance convert to political power? Unknown. The present Congress, for all its collaborations with Trump, has thwarted some of the Republicans’ incipient stampedes. Still, he has already done great damage through executive orders, through appointments hostile to public missions and the allocation of political commissars to run the executive branch. What will happen when lower-court decisions arrive at the Supreme Court for final disposition is by no means clear.

During the Nixon years, violence and intimidation against the resistance were rather coordinated. The printers that published underground papers were intimidated to stop by the FBI. The conspiracy trials of activists were centrally mobilized. Today, there are many more wild cards. The white supremacists are organized, and getting more so. (Not that vigilantes were unknown in the ‘60s. Murders of civil rights activists by Klansmen and other white supremacists were legion. Offices of underground papers were shot into and burglarized. In 1969, the early SDS leader , a visible anti-war activist, was savagely assaulted and almost killed in his office at the University of Chicago. The assailant was never found.)

Here’s an indisputable fact from the past that should not be forgotten: As the Vietnam war became less popular, so did the increasingly confrontational anti-war movement. The residue of the New Left trailed off into suicidal bravado. One thing that doesn’t change is that fringe activists who harbor revolutionary fantasies and shrug off their real-world impact frighten the unaffiliated and win cheers for “law and order,” even from citizens who disagree with the president’s policies. Demonstrations then were hijacked by flag-burners and arsonists. Today, they’re hijacked by window-smashers and go-for-broke black-bloc goons. Armed collisions between racist militias and antifa bullies are all too plausible. As we learned in Charlottesville, the police haven’t yet figured out how to dampen the lethal potential. Then and now, the slug-first-ask-questions-later thugs muddy the prospects for nonviolent change. They panic the bulk of the population. They promote the version of “law and order” that comes from the mailed fist.

Add that it’s by no means clear that the commander-in-chief of the White House has the slightest respect for constitutional processes. The sum of his grandiosity and recklessness, and the grandiosity and recklessness of his violent opponents, is the reason why, today, all bets are off.

Want to fix America’s health care? First, focus on food

(Credit: AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall, File)

The national debate on health care is moving into a new, hopefully bipartisan phase.

The fundamental underlying challenge is cost – the massive and ever-rising price of care which drives nearly all disputes, from access to benefit levels to Medicaid expansion.

So far, policymakers have tried to reduce costs by tinkering with how care is delivered. But focusing on care delivery to save money is like trying to reduce the costs of house fires by focusing on firefighters and fire stations.

A more natural question should be: What drives poor health in the U.S., and what can be done about it?

We know the answer. Food is the number one cause of poor health in America. As a cardiologist and public health scientist, I have studied nutrition science and policy for 20 years. Poor diet is not just about individual choice, but about the systems that make eating poorly the default for most Americans.

If we want to cut down on disease and achieve meaningful health care reform, we should make it a top nonpartisan priority to address our nation’s nutrition crisis.

Food and health

Our dietary habits are the leading driver of death and disability, causing an estimated 700,000 deaths each year. Heart disease, stroke, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, cancers, immune function, brain health – all are influenced by what we eat.

For example, our recent research estimated that poor diet causes nearly half of all U.S. deaths due to heart disease, stroke and diabetes. There are almost 1,000 deaths from these causes alone, every day.

By combining national data on demographics, eating habits and disease rates with empirical evidence on how specific foods are linked to health, we found that most of problems are caused by too few healthy foods like fruits and vegetables and too much salt, processed meats, red meats and sugary drinks.

To put this in perspective, about twice as many Americans are estimated to die each year from eating hot dogs and other processed meats (~58,000 deaths/year) than from car accidents (~35,000 deaths/year).

Poor eating also contributes to U.S. disparities. People with lower incomes and who are otherwise disadvantaged often have the worst diets. This causes a vicious cycle of poor health, lost productivity, increased health costs and poverty.

What a poor diet costs

It’s hard to fathom how much our country actually spends on health care: currently US$3.2 trillion per year, or nearly 1 in 5 dollars in the entire U.S. economy. That’s almost $1,000 each month for every man, woman and child in the country, exceeding most people’s budgets for food, gas, housing or other common necessities.

Diet-related conditions account for vast health expenditures. Each year, cardiovascular diseases alone result in about $200 billion in direct health care spending and another $125 billion in lost productivity and other indirect costs.

At the same time, health care costs cripple the productivity and profits of American businesses. From small to large companies, crushing health care expenditures are a major obstacle to growth and success. Warren Buffet recently called rising medical costs the “tapeworm of American economic competitiveness.” Our food system is feeding the tapeworm.

Yet, remarkably, nutrition is virtually ignored by our health care system and in the health care debates – both now and a decade ago when Obamacare was passed. Traveling around the country, I find that dietary habits are not included in the electronic medical record, and doctors receive scant training on healthy eating and other lifestyle priorities. Reimbursement standards and quality metrics rarely cover nutrition.

Meanwhile, total federal spending for nutrition research across all agencies is only about $1.5 billion per year. Compare that with more than $60 billion spent per year for industry research on drugs, biotechnology and medical devices.

With the top cause of poor health largely ignored, is it any mystery that obesity, diabetes and related conditions are at epidemic levels, while health care costs and premiums skyrocket?

Moving forward

Advances in nutrition science highlight the most important dietary targets, including foods that should be encouraged or avoided. Policy science provides a road map for successfully addressing our country’s nutrition crisis.

For example, according to our calculations, a national program to subsidize the cost of fruits and vegetables by 10 percent could save 150,000 lives over 15 years, while a national 10 percent soda tax could save 30,000 lives.

Similarly, a government-led initiative to reduce salt in packaged foods by about three grams per day could prevent tens of thousands of cardiovascular deaths each year, while saving between $10 to $24 billion in health care costs annually.

Companies across the country have been rethinking their approach to employee health, providing a range of financial and other benefits for healthier lifestyles. Life insurance has also realized the return on the investment, rewarding clients for healthier living with fitness tracking devices, lower premiums and healthy food benefits which pay back up to $600 each year for nutritious grocery purchases. Every dollar spent on wellness programs generates about $3.27 in lower medical costs and $2.73 in less absenteeism.

Similar technology-based incentive platforms could be offered to Americans on Medicare, Medicaid and SNAP (formerly known as Food Stamps) – together reaching one in three adults nationally. In 2012, Ohio Senator Rob Portman proposed a Medicare “Better Health Rewards” program to reward seniors for not smoking and for achieving lower weight, blood pressure, glucose and cholesterol. This program should be reintroduced, with updated technology platforms and financial incentives for healthier eating and physical activity.

Several other key strategies should be added, together forming a core for modern healthcare reform. Incorporating such sensible initiatives for better eating will actually improve well-being while lowering costs, allowing expanded coverage for all.

By any measure, fixing our nation’s nutrition crisis should be a nonpartisan priority. Policy leaders should learn from past successes such as tobacco reduction and car safety. Through modest steps, we can achieve real reform that makes healthier eating the new normal, improves health and actually reduces costs.

By any measure, fixing our nation’s nutrition crisis should be a nonpartisan priority. Policy leaders should learn from past successes such as tobacco reduction and car safety. Through modest steps, we can achieve real reform that makes healthier eating the new normal, improves health and actually reduces costs.

Dariush Mozaffarian, Professor of Nutrition, Tufts University

Campus cannabis: The top 7 stoniest small colleges

(Credit: AP Photo/Brennan Linsley, File)

The Princeton Review has released its annual compendium of rankings and ratings of institutions of higher learning across the land, The Best 382 Colleges 2018 Edition, and buried deep inside are student survey results that helped the Review determine which colleges and universities are the most (and least) marijuana-friendly.

In addition to a myriad of questions about academics, diversity and community, the survey asked 137,000 students “How widely is marijuana used at your school?”

Before getting to the list, a couple of caveats: First, the survey data is impressionistic — asking respondents how many other students they thought were tokers instead of asking for self-reporting, which would theoretically be more reliable. Second, the Review provides no hard numbers — just rankings — so it’s impossible to know if Ithaca College is way stonier than Bard or just a bit stonier.

That said, the general outline of the pot-friendly small colleges skews heavily to the liberal arts and the Northeast, and New York state in particular, with a couple of outliers on the .legal West Coast and one on the not-so-legal Gulf Coast. Pot isn’t legal in the Empire State, but it is decriminalized — and apparently pretty popular.

Here, in rank order, are the Princeton Review’s stoniest small colleges:

1. Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY

Enrollment: 6,221

This is a school in a town where the mayor wants to install safe injection sites for hard drug users, and enlightened attitudes toward pot are no surprise.

2. Bard College, Avondale-on-Hudson, NY

Enrollment: 1.995

The school lives up to its reputation.

3. Eckerd College, St. Petersburg, FL

Enrollment: 1,844

Who knew?

4. Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY

Enrollment: 2,680

Fun Day is more fun, and the National Comedy Festival is funnier when you’re baked. This liberal arts college, a perennial high-ranker, was #1 in 2013.

5. Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT

Enrollment: 2,971

Inspiration for the ’90s film PCU poking fun at campus activism, the school generates a steady stream of artists, actors, and musicians. What’s inspiring them?

6. Reed College, Portland, OR

Enrollment: 1,410

Of course.

7. Pitzer College, Claremont, CA

Enrollment: 1,089

Part of the Claremont Colleges, this LA-area school is highly ranked academically, but includes intercollegiate athletics, too. Go, you fightin’ Sage Hens!

Altitude sickness in the upwardly mobile

(Credit: Salon / Ilana Lidagoster)

On the way back from our trip to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s homestead in the Missouri Ozarks, my mother and I pit-stopped in a McDonald’s parking lot after the drive-thru attendant told us the restaurant didn’t accept checks. We were returning to our own home in the Arkansas Delta so broke that Mom ran her arm, up to her elbow, beneath the seats of her Grand Am, fishing for enough change to buy a single cheeseburger. The souvenirs she’d splurged on in the days before — a boxed set of Wilder’s “Little House” series and a t-shirt for me and two framed sepia photos of me in period Western wear, including one for my father, whom Mom had recently divorced — sprawled across the back seat, and I slumped in the passenger seat, heading my bounty, incapacitated with a migraine.

“Maybe you just need to eat something,” Mom had said, and so she finally gathered 72 cents, and, as often was her way in those days, she went hungry. I ate, and then miles down Highway 63, as often was my way in that debilitated state, I puked.