Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 44

March 9, 2019

Kerala women politicians bemoan the lack of opportunities

By Shevlin Sebastian

Pics: Veena George; Savithri Lakshmanan, the last woman Congress MP. Her term ended in 1991

On March 9, when Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, secretary of the CPM announced the list of candidates for the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, there was a collective groan from the women politicians of the state. Once again, the woman representation in the LDF is dismal. They have got only two out of 20 seats: Sreemathi Teacher and Veena George.

“We are not surprised,” says a woman politician, on condition of anonymity. “This is a patriarchal society.”

Now the top leaders of the Congress Party have had parleys over different names. One woman Congress politician says, “I have presented my case.” So, does she stand a chance? “Not sure,” she says. “Our party has not had a woman MP for the last 25 years, since Savithri Lakshmanan. Hope we will get a chance to break the trend.”

Another Congress politician says, “Even if we get seats, we are usually allotted the losing ones. In 2014, we got Alathur and Attingal. There are rumours this will be the case this year.”

The names will be sent to the High Command and the final decision will be made in Delhi. The announcement will be made on Monday. The BJP is also expected to announce their list soon.

In 70 years of electoral politics, Kerala has had only eight women MPs: Annie Mascarene, Susheela Gopalan, Bhargavi Thankappan, Savithri Lakshmanan, AK Premajam, P Sathidevi, CS Sujatha and Sreemathi Teacher. “This is sad especially because the women voters outnumber the men,” says politician Beena Menon (name changed). “And how are we inferior to men? We work as hard and are as dedicated.”

On March 8, when Beena was travelling in a car from Kollam to Thiruvananthapuram she was flipping through the Woman’s Day supplements of various newspapers, extolling the achievements of women and felt nice. But soon, she reflected on her own career in a political party and began to feel depressed.

“When a woman joins politics at the grassroots level, she is not given any respect by their male colleagues,” she says. “The men think that if she is coming to politics, she is not morally upright. As a result, there have been moments where women have been in uncomfortable situations. But they keep quiet about it. That’s because, in a male-dominated society, it is difficult to get justice.”

And even if she works as hard as her male counterpart it is the latter who gets most of the posts. “Till now, no woman has become the president of the party,” says Beena. “At the most, they become the president of a district committee. But the numbers are very low. Out of 100 district committees, say, there will be only or two women leaders.”

Beena says that this should change. “We desperately need a change in the mindset of society,” she says.

(The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on March 09, 2019 20:46

March 8, 2019

It’s all bright and shining

A few weeks after they moved into their well-made houses, residents of the ‘God’s Villa’ of the Kizhakkambalam Panchayat talk about their experiences

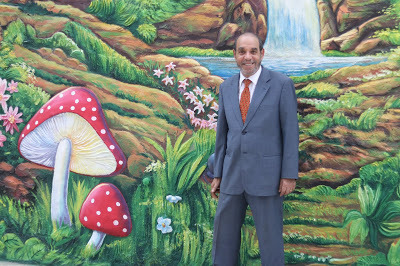

Photos: The colony before the change; Sabu M jacob, Chairman and Managing Director of the Kitex Group; the colony today

By Shevlin Sebastian

The sun is beating down fiercely at noon on a day in March at ‘God’s Villa’ of the Kizhakkambalam Panchayat. Nobody seems to be around. The tiled road between the houses is deserted. It would have been completely silent except for a few voices that are emanating from a TV set at widow Subhadra P’s house. The seventy-year-old, wearing a maroon nightgown, is indeed relaxing by watching a show. Her daughter, who is staying with her, has gone to work as a teacher in a nearby school, while Subhadra’s 13-year-old grandson is also at school.

And Subhadra is in a happy mood. “At this moment we are living in paradise,” she says. Subhadra and her family moved into a brand-new house three months ago. It has been built by ‘Twenty20 Kizhakkambalam’, a CSR initiative of the Kitex Group, along with the Kizhakkambalam Panchayat.

“We were shocked when we saw the finished house,” says Subhadra. “It is so well-made. We never thought that one day we would have the luck to stay in such a beautiful house.”

The 750 sq. ft. house is set on four cents of land. There are two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a living-cum-dining room and a kitchen. There is a small work area at the back. Outside, there is a car parking facility. Earlier, water connections had also been provided. There is a storage tank of 1000 litres.

Subhadra has also bought a dining table, beds, TV, sofa, and a mixer/grinder at half the price, Rs 1 lakh, from Twenty20.

It is no surprise that Subhadra calls her house a paradise. She had been living in a 240 sq. ft house which she got through the Laksham Veedu Colony (One-Lakh Housing Scheme) which was initiated by the State government in 1972 to help the landless. “But we had to share the house with another family. So we had only 120 sq. ft. A single wall was the divider,” says Subhadra. “We lived in two rooms and had a small kitchen. The houses were not maintained properly.”

As Subhadra busies herself filling glasses with ginger juice, neighbour PP Murali drops in. The 56-year-old painter has been living in the area for decades. “In my childhood, eight people -- my parents, my sister, two cousins and my two grandmothers lived in a tiny space.”

He is deeply grateful to the chairman & managing director of the Kitex Group Sabu M Jacob. “Their family has been doing good work in our village for generations,” he says. “They have set up a mall where we can buy essential items at only 50 per cent of the selling price.”

And other types of help are also being rendered. Recently, one of their neighbours, a forty-year-old woman was suffering from cancer. “Sabu Sir paid almost the entire cost of the treatment and now the lady is well and has gone back to work,” says Murali.

There has been a change in the psyche of the people. Says one resident, “Today, my identity has been changed from Peter Abraham, Laksham Veedu Colony to Peter Abraham, God’s Villa, 2037- Central Drive. This has increased our confidence, our standard of living and will have an impact on future generations.”

Peter is also happy that the crime rate has gone down drastically. “Earlier, it was a hotspot of criminals, drunkards and drug addicts,” he says. “Many fights would take place.”

Incidentally, the cost of rebuilding 38 houses of this colony is Rs 6 crores, out of which Twenty 20 has spent Rs 5.26 crore while the panchayat gave Rs 74 lakhs.

The biggest impact of the panchayat’s work has been the loss of image for the political parties. “The Twenty20 Kizhakkambalam’ has shown us that what political parties were not able to do in 71 years, they did it in four years,” says Murali, who was once a CPI party worker. “This is the only panchayat where all the political parties -- be it the CPI(M), Congress or the BJP -- have joined hands to oppose the panchayat. But the people are firmly behind Sabu Sir.” Murali says that he is certain Twenty20 Kizhakkambalam will sweep the next elections in 2020.

Sitting at his dining table on the ground floor of the spacious Kitex headquarters, moments after lunch, Sabu Jacob is nursing a sore throat. So he sips a cup of hot green tea. Asked why the company has been so generous, Sabu says, “Right from my grandfather’s time we have always been helping the people. My father always told me that when the business grows, the locality should also grow. That is sustainable growth.”

Once his father told Sabu, “Look at Mumbai. Somebody lands at the airport, he will say, ‘what an excellent place’. But when they come out what they are seeing on both sides is the Dharavi slum, the largest in Asia. So that should be changed.”

Sabu pauses and says, “Every year we are growing, and our resources are increasing. So, we are pumping in more money into the community.” (Kitex, which has 10,000 employees, is the third largest producer of children's apparel in the world).

Sabu acknowledges that the political parties have ganged up against him. And recently, when work had begun to make a rubberised road, there was opposition from the politicians and the work has come to a standstill. “The matter is in the court now,” he says.

Unlike most roads which have a thickness of 2 cms officially, but actually is less than 1 cm, these rubberised roads will have a thickness of 45 cms. “If the drainage is done scientifically, these roads will last for 25 years,” says Sabu. “So, you can understand why they would not want a road like this to be built in our panchayat.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on March 08, 2019 22:12

March 6, 2019

People without a country

Malappuram native Nipin Gangadharan talks about his experiences of dealing with the Rohingyas at camps in Bangladesh. He is the country head of a French NGO

Photos: Nipin Gangadharan; a girl at the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp, at Cox’s Bazaar. Pics taken by Jean Sebastien Duijndam/Action Against Hunger

By Shevlin Sebastian

In September 2017, the Malappuram native Nipin Gangadharan stood at the entrance of the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp, at Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh, as a stream of Rohingya refugees arrived on the back of trucks. They were fleeing the violence meted out by Myanmar soldiers who allegedly burnt their houses, raped their women and shot dead protestors.

Nipin noticed a 40-year-old man. He was standing immobile. “This person looked completely lost,” says Nipin, who is the Country Director of ‘Action Against Hunger’, a French non-profit humanitarian organisation. “He had this look of horror in his eyes. There was no light on his face. And he was not comprehending what we were saying.”

Nipin immediately understood that more than food and shelter, the man needed psychological help. So he got a counsellor to talk to the man so that the refugee could articulate the trauma he went through and start healing in some way.

This camp is spread over 4000 acres but that is clearly not enough because there are 6.2 lakh people present. “In total, there are nearly 10 lakh Rohingyas in Bangladesh now,” says Nipin.

A lot of the forest land has been denuded because wood had to be cut for cooking. “There has been a lot of damage to the environment,” says Nipin. So now, aid agencies are rushing to provide gas cylinders and solar equipment.

YouTube videos reveal bamboo huts with thatched roofing. Sometimes, tarpaulins have been used. A child collected water in a plastic bottle from a ditch. The colour, not surprisingly, was yellow. A woman, in a hijab, holding a small child was crying. Another woman, in a long gown, but with a tired looking face, was sleeping on the mud floor of a hut in which the walls had not yet been put up.

And when they do come up, there is a danger that it could come down again. That’s because Cox’s Bazaar is a cyclone-prone area. There is heavy rainfall period between June and September. So the chances of cyclones occurring every year or every other year are very high.

As for the Rohingyas, it has been a time of distress and uncertainty. “They are trying to get used to this new life in the camps,” says Nipin. “The transition has been hard to bear.”

These were people who were living in individual houses, had their own farms and could walk around their homesteads freely and without fear in the state of Rakhine in Myanmar. Now they are living in slum-like conditions, with few social services, and not enough policing. “So that makes it very stressful,” says Nipin. “The people are not comfortable. It’s not nice to be living in a camp-like situation. All of them want to go back to Rakhine. But they want their rights, and to be treated with respect and dignity.”

Meanwhile, when asked about the attitude of the people of Bangladesh, Nipin says, “They feel overwhelmed. When the influx started, there was a deep empathy. The Bangladeshis provided food and water and opened up their homes. But as this influx continues, tensions are rising.”

One reason is because the Rohingyas are now competing for resources with the local people in an area which is traditionally not very well off. Since the refugees have not been given the right to work, and earn a living, they work in informal economies, doing manual work, which brings down the cost of labour and the locals lose out.

But there is a silver lining. “Because this has become a major humanitarian operation, there are a lot of employment opportunities,” says Nipin. “This benefits the local people. And because of construction activities, a lot of new businesses have come up.”

Nevertheless, the Bangladesh government do not want the Rohingyas to stay too long. “They want them to go back from where they came from,” says Nipin. “That is the crux of the negotiations that are going on between Myanmar, Bangladesh, regional as well as global powers.”

But Nipin is pessimistic because when you look at the history of forced migration, people don’t go back soon. “The Rohingya crisis has lasted for three decades,” he says. “I believe it will take another two to three decades before the people can start going back.”

Which means that many refugees will probably die in the camps. And the future of the children seems to be bleak.

As for whether any education is being provided, Nipin says, “Education is a bit tough. There is a lack of space. Congestion is quite high. People are crammed in a very small area. But there are many organisations, including UNICEF, which have set up learning spaces where children can come and learn.”

The children have spoken about their dreams of becoming doctors and engineers. But Nipin, with a sad shake of his head says, “They are stateless. So they cannot go anywhere. At the most, they can become teachers in the camps.”

Meanwhile, the question now arises as to whether Myanmar has committed genocide. “The Canadian Parliament called it a genocide and so did the Americans,” says Nipin. “Genocide is defined as the intent to eliminate a person or a group because of their identity.”

And this has been the case with the Rohingyas. They have been persecuted for decades. And in this recent instance, which triggered the influx into Bangladesh, they were deliberately targeted. “There is a historical background to the hostility between the Rohingyas and the Myanmarese,” says Nipin. “The military junta exacerbated some of these social tensions and converted it into animosity and hatred for the Rohingyas. It is a tragedy because once upon a time, all the communities used to live peacefully together.”

------

Helping the distressed

Before arriving at Bangladesh in January, 2016, as the country head of the French NGO, ‘Action Against Hunger’, Nipin Gangadharan worked in South Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Nepal and the New York offices of the NGO in various capacities.

He has also worked with national and international charity organisations as well as the United States in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan, on reconstruction efforts after the Gujarat Earthquake (2001), and relief and rehabilitation following the Indian Ocean tsunami (2004).

Nipin, who is from Tirur, Malappuram, holds a MA in International Affairs with specialisation in conflict and security issues from the New School University in New York.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Kozhikode and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on March 06, 2019 00:57

February 28, 2019

On an endless run

The Aluva-born Nixon Joseph, is the oldest marathon runner among the 2.7 lakh employees of the State Bank of India as well as the first Indian banker to complete 30 marathons.

By Shevlin Sebastian

On February 4, Rajnish Kumar, the chairman of the State Bank of India stood on an open-air stage in Mumbai and said, “I congratulate Nixon Joseph for his inspiring achievement. Doing things differently inspires everyone and he is a good example.”

Nixon, who is the President and Chief Operating Officer of the SBI Foundation, was being felicitated for completing 25 full marathons. At 57, he is the oldest marathon runner among the 2.7 lakh employees of the bank as well as the first Indian banker to complete 30 marathons.

Some of the places he has run include Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Hokkaido, Phuket (Thailand), Singapore, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Shillong, Cherrapunji, Delhi, Gurugram, Satara (Maharashtra), Pune and Mumbai.

And it all began rather accidentally. One day, when he was 44 years old, he realised that all bankers did more or less the same job. “From the top to the junior-most all are career bankers,” says Nixon. “I could not find anything different. I always felt that someone should look at you and say that you are inspiring. I wondered how I could be different.”

That was when he saw an advertisement in a newspaper asking for entries for the Standard Chartered Mumbai marathon. So, he decided to participate. “Even though it was 42.195 kms, I could not comprehend the distance,” he says.

Nevertheless, Nixon bought canvas shoes worth Rs 300 and set out. After seven kms, the soles came off. His feet started paining. Blisters added to the discomfort. “It was like being in hell,” says Nixon. But he decided he would not give up. But when Nixon reached 30 kms, he thought, ‘Why am I doing this? I should stop now’. But somehow, he felt he had to complete the race. In the end, it took him seven hours and fifteen minutes to finish.

Following that, Nixon was awarded a finisher’s medal. The next day when he took the medal to the office, many people congratulated him. “That was when I realised that 42 kms is a long distance,” says Nixon.

He began training in earnest. But his turning point came when he was posted to Japan in 2008. “In Tokyo, there is an environment that encourages all kinds of physical activities,” says Nixon. “I saw 85-year-old men and women doing jogging, swimming, cycling, and working out in the gym. There were numerous running and jogging tracks, as well as many playgrounds. Another advantage was the pleasant weather. I felt very motivated. I was thinking, ‘If an 80-year-old man can jog, why cannot I?’

Even workaholics looked after their bodies. “My colleague used to leave office at 10 p.m., and go to the gym. He would work out for an hour before going home,” says Nixon. “I felt that age should not be a barrier to achieve our dreams.”

Soon, Nixon began participating in marathons. And when he returned to India, after his four-year stint, he continued to do so. “The Indian attitude is, ‘You are getting old, relax, don’t do anything’,” says Nixon. “But what most people don’t understand is that running energises me. I don’t feel that I am aged. I have always felt young,” says Nixon.

He added that running made him determined, bold, and sharpened his brain. “You tend to carry this behaviour to the office, and end up performing better,” he says.

When the SBI launched green marathons (21 kms, 10 kms and 5 kms) in October, last year, to promote sustainability Nixon volunteered to run, to inspire the bankers. “I have taken part in eleven races, so far,” he says.

And people are aware of his achievements. “Whenever I go to a SBI branch and am introduced, many tell me that I inspire them,” says Nixon, who is a regular motivational speaker at colleges and institutions.

Asked how he prepares for marathons, Nixon says, “Since I am running a marathon once every three months, I am always in training.” He runs one hour a day and three hours on the weekend. Nixon leads a disciplined life. He goes to sleep early. He does not smoke and is only a social drinker. He avoids using the elevator. The corporate headquarters in Mumbai has 19 floors. Nixon used to work on the sixth floor. Whenever he had to meet the top executives on the 18th floor he would walk up the stairs. “It increases your endurance levels and stamina,” says Nixon, who was born in Aluva.

His father worked in the Life Corporation of India while his mother was a homemaker. Nixon did his graduation from UC College and got the third rank. He also studied at Government Law College, before he got selected in SBI as a probationary officer. He is married to Rose, a homemaker, and has two daughters, Priya, 23, and Swapna, 21.

Asked about his future plans, Nixon says, “My immediate aim is to run 50 marathons.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 28, 2019 22:17

February 20, 2019

Here are all the answers…

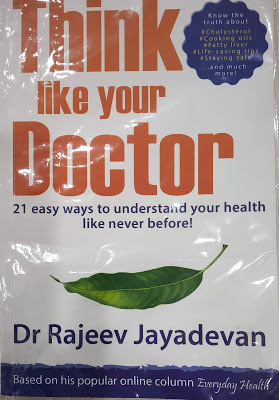

Gastroenterologist Dr Rajeev Jayadevan, in his book, ‘Think Like Your Doctor’ analyses, in simple language, the common health and social problems that affect most people

By Shevlin Sebastian

‘Manju, a 26-year-old IT professional working long hours in Kochi, developed a nagging pain in the centre of her chest. She didn’t have the time to consult a doctor, and so did what many people do in such situations -- search the internet for a solution. Her Google search left her convinced that all of her symptoms pointed to terminal heart disease and that her days were numbered.

She was no longer able to focus on her project, became irritable and frequently showed up for work tired from lack of sleep. She was already worried about how her dependents would cope with her absence.

Alarmed at her change in demeanour, Manju's colleagues took her to a doctor. After taking a detailed history including questions on her lifestyle, her doctor ordered a couple of blood tests and told her that she had acidity from irregular meal timings and excess consumption of cola. Within two weeks, Manju was back to her cheerful, healthy self.

Manju’s story is a typical case of 'cyberchondria', defined as the excessive use of internet health sites that fuel health anxiety. The difference between Google and doctor, in this case, was that while the internet provided Manju with a long list of the possible diagnoses, the doctor was able to dig out pertinent lifestyle clues from her history using medical knowledge, correlate with the past experience of similar patients, and arrive at a single diagnosis.’

This is an excerpt from the article, ‘Who is better: doctor or Google?’ from the book, ‘Think Like Your Doctor’. It has been written by the gastroenterologist, Dr Rajeev Jayadevan, the deputy medical director of Sunrise Hospital. The book, which has been published recently, has been received well. The writing is simple and accessible, and the book makes for an easy read.

It is a compilation of articles that Jayadevan had written for a vernacular online platform. The subjects include memory loss in old age, a user’s guide on painkillers, information overload, the truth about cooking oils, and first-aid tips.

Meanwhile, in his job as a gastroenterologist, Jayadevan sees a lot of liver disease. And he is not surprised. Because a significant number of Malayali men are heavy drinkers. “About 50 percent of liver cirrhosis cases in Kerala are caused by drinking,” he says. “Many of them are unable to stop drinking because they are addicted.”

And the amount of money and effort that goes into the treatment, it ends up devastating a family's finances. “It is a self-inflicted blow,” he says.

When he came to know that most had started drinking in their teens, he started going to schools and colleges to urge them to stay away from alcohol and drugs. This is what he tells the students: “I am not here to tell you what to do. I am here to give you precise information from my personal experience as a doctor about what happens when you drink too much or take drugs. Now you can look at this information and decide what you want to do.”

Through his interactions, Jayadevan discovered the astonishing fact that the average age when men start drinking is 13. “According to published data, 25% of our high school boys are using alcohol,” he says. “It is a major issue.”

Another issue is the lack of exercise. Jayadevan knows of elite sportsmen in college, who once they finished their studies, stopped exercising, and became obese. “Their mothers want them to be fat,” he says. “Society, too, wants them to become fat. As a result, by the time they are 30, they have been diagnosed with diseases A, B, C and D. These used to be diagnosed earlier at 50 and 60.”

Another problem is that online users tend to believe everything that is published on the Internet. “There are articles which state that having garlic or ginger juice is good for health,” says Jayadevan. “It might sound plausible, but there is no hard evidence to prove it. People can be very gullible, but it can have devastating consequences.”

Once, there was a widespread rumour that the juice from the bilimbi (chemeen pulli), which grows widely in Kerala, is good at reducing cholesterol. Many people put a large quantity in the blender, made a juice and drank it. Unfortunately, it was full of oxalate. “All the oxalate clogged the kidneys and it shut down irreversibly,” says Jayadevan. “Some were lucky to get a transplant, while others had to go into dialysis for the rest of their lives.”

The Kochi-born Jayadevan did his MBBS and MD from Christian Medical College, Vellore in 1995. He went on to study Clinical Epidemiology and Public Health at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Later, he was awarded the MRCP from the UK in 1996. He also obtained Medicine and Gastroenterology (Fellowship) from New York Medical College. Thereafter, he spent three years in the UK and 10 years in the US. As he wanted to take care of his ageing parents, he returned to Kochi ten years ago.

Asked whether he likes his medical job or writing, Jayadevan smiles and says, “Both bring me joy.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 20, 2019 02:42

February 18, 2019

The wonder that is Cochin

City historian Balagopal CK, in association with Sahapedia, an encyclopedia on Indian arts and culture, organised a Heritage Walk about the coastal city to make people aware of its cultural legacy

City historian Balagopal CK, in association with Sahapedia, an encyclopedia on Indian arts and culture, organised a Heritage Walk about the coastal city to make people aware of its cultural legacyPhotos: Balagopal CK; the Abdicated Highness King Rama Varma XV

By Shevlin Sebastian

City historian Balagopal CK stood in front of the Durbar Hall in Kochi on a recent afternoon accompanied by a group of people, which included architects, writers, students and hoteliers. Balagopal, in association with Sahapedia, an encyclopedia on Indian arts and culture, was organising a Heritage Walk titled, ‘Tracing the Journey of Ernakulam Town in Modern Times’. The walk highlights the period from the early 1800s to the time of Independence.

“For a long while, the Darbar Hall was the administrative centre of ‘Cochin’, as it was known then,” says Balagopal. “And how it happened is an interesting story by itself.”

In 1808, the Dewan of Travancore, Velu Thampi, and the Chief Minister of Cochin, Paliyath Achan Govinda Menon hatched a plan to kill the British Resident Colin Campbell Macaulay (1760-1836), who was staying at the Bolgatty Palace island. Both felt that the British control of India was coming to an end. So they thought it would be the right time to kill Macaulay. The King of Cochin, in whose territory the attempt was made, remained a mute spectator.

“The attack was led by Chempil Arayan, who was the Admiral of the fleet of the Travancore King Balarama Varma,” says Balagopal. “The latter had also fallen out with Macaulay.”

The attackers arrived in boats, at night. More than 300 muskets were fired. But Macaulay fled through an underground tunnel and escaped on a boat. Soon after, the British were able to arrest Chempil. Thereafter, they moved the administrative seat from Mattancherry to the Durbar Hall in Cochin and appointed new people in positions of power. They were called the Diwans. The Kings became constitutional heads.

Then Balagopal moved a few hundred metres away, towards a temple, and says, “This is the Ernakulathappan Siva Temple, which is part of the Durbar Hall grounds.” Ernakulathappan is the Lord Of Ernakulam (older name of Kochi). It was believed to have been built under the patronage of a local chieftain called Cheranellur Kartha but it was renovated and raised to the level of a royal temple by Diwan Sri Edakkunni Sankara Warrier in 1846.

At the General Hospital, Balagopal says, “This hospital provided very good health care. In 1898, King Rama Varma XV (1852-1932) imported an X-ray machine from Britain to treat his mother. However, the British Medical Officer said it was too much of a luxury for the people and refused to pay for it. In the end, the King had to foot the bill himself.”

Rama Varma XV was also known as the Abdicated Highness. That’s because he abdicated the throne in 1914. “He had his disagreements with the Resident,” says Balagopal. “He was shaking up the system. The British establishment was not happy.”

However, the seeds of modern Cochin were sowed during his reign, as he introduced the Shoranur-Cochin railway line, a distance of 96 km, established the Sanskrit College at Tripunithura, and brought in a village panchayat bill and the Tenancy Act. “In fact, when the Viceroy Lord Curzon came to Cochin on a visit, he called it the most progressive state in India,” says Balagopal.

At the Maharaja’s College, Balagopal says, “The college was started by the Cochin government as an English-medium school in 1875. The first principal was a British gentleman called A F Sealy. It was rechristened as Maharaja’s College in the 1920s. It did have the patronage of the Maharajas. The princes of Cochin and Kodungallur studied here. However, they sat at one side, away from the commoners. In a way it was elitist.”

Very few people had access to education. “In the 1900s, the literacy rate was 14 per cent for men and 4 per cent for women, which is abysmal by today’s standards,” says Balagopal. “However, in those times, it was the highest in South India, after the Madras district, and way above the national average.”Some of the other places he showed include the TDM Hall, the Cochin Corporation, and the Harbour.

Finally, Balagopal took the group to the Mahatma Gandhi statue on Foreshore Road, near the Harbour. “Cochin was the first Princely state, of the 565 states, to join the Indian Union in 1946,” says Balagopal. “When the first Constituent Assembly met in 1946, Cochin was the only princely state to sent elected representatives. It was a precursor to democracy.” Interestingly, Balagopal was a Mysuru-based engineer. But he relocated to Kochi in 2016 and saw, to his dismay, many large historical buildings being torn down. “It was disheartening,” he says. “There was so much of heritage that was being destroyed. So I wanted to start a conversation about our history and create an ethos of conservation. In a way, I am trying to do my bit to preserve our cultural riches.”

---------

A statue for a king At the Subhash Park, Kochi, there is a statue of Rama Varma XV. The Diwan of Cochin AR Banerjee saw the statue of Ganga Singh, the Maharaja of Bikaner and wanted to make a similar statue in the name of Rama Varma XV. “But by this time World War 1 broke out,” says Balagopal. “Metal became very dear. If you wanted to use metal for anything, apart from armaments, you needed special permission. So, nothing happened. It was later made at 1300 pounds, way above the original estimate of 500 pounds. But by then, the King had abdicated.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on February 18, 2019 23:38

Loving Art With All Her Heart

Kiran Nadar, one of India’s leading art collectors, talks about her experiences while on a recent visit to the Kochi Muziris Biennale

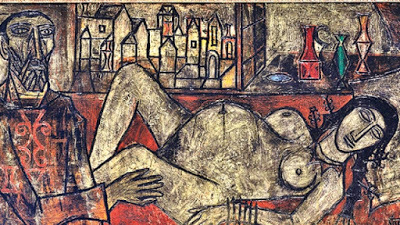

Photos: Kiran Nadar; FN Souza's 'Birth'

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, several years ago, art collector Kiran Nadar went to see the artist Rameshwar Broota at his studio in New Delhi. He received her warmly. Thereafter, he showed a work. It was a triptych of male nudes. She loved the work and agreed quickly to buy it. Thereafter, Kiran took some images on her mobile.

At home, she showed the photos to her husband, Shiv Nadar, the billionaire chairperson at HCL Technologies. He was horrified and told Kiran, “How can you buy it? Our daughter is only five years old. My mother lives with us for six months of the year. What will she think?”

Kiran replied, “I had told Rameshwar that I would buy it. But now if we are not, we have to show the courtesy to go back and say, ‘Sorry, we are unable to take it forward’.”

Shiv agreed. One evening, the couple went to Rameshwar’s gallery. But when Shiv saw the painting, he said, “You are right, Kiran. We have to get it.”

And today, the painting hangs in the study of Shiv’s house.

This was the story that Kiran immediately remembered when asked about her experiences as one of India’s leading art collectors, as she sipped a glass of watermelon juice at the Taj Malabar. She had recently come to see the fourth edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, curated by the Delhi artist Anita Dube.

And Kiran enjoyed what she saw. “I liked the way Anita placed an emphasis on women artists,” she says. “Her approach is very humane. The earlier curators, like Bose [Krishnamachari] and Riyas [Komu], Jitish [Kallat] and Sudarshan [Shetty] all brought a different and unique sensibility.”

The artwork that impressed her the most at this year’s edition was South African artist William Kentridge’s eight-video installation called ‘More Sweetly Play The Dance’, as well as the four-wall installation by Gond artists Subhash Singh Vyam and his wife Durga Bai.

As to whether awareness of art has increased among the common people, Kiran says, “To some extent, it has increased among the public in Kochi, Mumbai and Kolkata. But in Delhi, it is still very low.”

However, that did not prevent her from putting up a state-of-the-art institution called the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, at Noida, which completed nine years last month. Sponsored by the Shiv Nadar Foundation, it is spread over an area of 40,000 sq feet, and houses more than 400 artworks. But the Foundation has about 5500 artworks stored in an air-conditioned facility. Incidentally, the most expensive artwork that Kiran bought, at a Christie’s auction, in 2015, was for FN Souza’s ‘Birth’. It was priced at Rs 30 crore.

Kiran selects works based on her intuition and emotional reactions. “Also, over the years, I have developed an eye for a good work,” she says. “Having said that, I am also open to somebody who wants to convince me about a particular work.”

Works are got through an auction, art galleries, or bought directly from the artist. “Some dealers show me the earlier works of an artist who has made a mark,” she says. “I might buy such a painting.”

As someone who interacts with artists, she has a good sense of their personalities. “Artists are complex people, because they have so many sides to them,” says Kiran. “But all of them are magnetic and charismatic, innately gifted, and have some sort of idiosyncrasy. Take MF Husain, for instance. On one level he was very generous and gracious. On another, he could be very calculating. On the third level, he would forget easily. He would leave a painting with you and completely forget about it. Yet he would express a thought that a particular painting was given away way too cheap.”

Asked to list her favourite artworks, Kiran says, “There is a painting by Raja Ravi Varma called Shakuntala. It is of Shakuntala writing a letter to a beloved in a forest, surrounded by two friends. It is very soothing to watch as there is a tenderness in the scene.”

Another favourite is an untitled painting by Manjit Bawa. “It’s about our world -- there is Kuberan, Hanuman, Krishnan, and the cows. The work has all the things that he was important for. He had done some black and white sketches for a national magazine. I had seen that and asked him to adapt it. I keep this at my home, but I do lend it to to the museum for Manjit Bawa shows.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvfananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 18, 2019 00:17

February 12, 2019

We care for you

With the help of tribal communities in Karnataka, Tarsh Thekaekara and his wife Shubhra Nayar have collaborated with tribal artisans to make elephants of the shrub lantana. Later, these elephants will be auctioned in the UK and USA to generate funds for elephant conservation

Photos: (From left): From left: Tarsh Thekaekara, his wife Shubhra Nayar, Subhash Gautam and Tariq Thekaekara; the elephants at Fort Kochi

By Shevlin Sebastian

One night, just outside elephant conservationist Tarsh Thekaekara and his wife Shubhra Nayar’s house in Gudalur, Tamil Nadu, a wild elephant stopped and reached out with its truck. An elephant made of lantana shrubs had been placed outside. But the wild elephant did not know that this was also an elephant.

“It did not smell or sound like one,” says Tarsh. “Also, it does not normally see very well. So, it could not conclude it was an elephant.”

But on South Beach, at Fort Kochi, a few days ago, bibliophile Joe Cleetus, on his morning walk, had no problems in concluding it was a series of elephants although it would only be later that he would come to know they were made of lantana. He rushed back home to get his camera. Well-known RJ Anjali Uthup Kurian wrote in a Facebook post, again on a morning walk, “I nearly jumped out of my skin as I had no contacts or glasses on. But the energy they had…”

These lantana elephants are indeed eye-catching. And each is a replica of an actual elephant. “It varies from 3 feet, all calves are about three feet and the largest male is about 10-and-a-half feet tall,” says Tarsh.

These will be on display at Fort Kochi for a month. Thereafter, it will be taken to Bangalore, Delhi, the UK and USA. The aim is to auction them and get funds for the Asian Elephant Fund. The project is being implemented by the Real Elephant Collective, a Kochi-based social enterprise, established by Shubhra and Tarsh’s brother Tariq Thekaekara.

They are in partnership with the UK-based NGO Elephant Family, which had funded the making of the first elephants. In total, there will be 100 elephants, out of which 60 have already been made. The other collaborators include the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, The Asian Nature Conservation Foundation, World Wildlife Fund-India and The Shola Trust, the last of which is run by Tarsh, Shubhra and Subhash Gautam.

Interestingly, there was a specific reason to use lantana. It is a South American shrub that was introduced by the British to India in 1809 as an ornamental garden shrub. It is very hardy and has bright orange flowers. The problem is that it has toxins in its leaves and so it cannot be eaten by animals. It puts out some chemicals that suppress the growth of other plants.

In Mudumalai and other neighbouring forests, about 14,000 hectares have been taken over by the lantana. “So, that’s as good as 30 per cent which is lost to the animals,” says Shubhra. “And it costs Rs 50,000 to clear one hectare. So the costs are prohibitive. The only way out is to create an industry out of lantana, like making paper, furniture, plywood and elephants, as we do.”

It was Shubhra who came up with the idea of making elephants out of lantana. A graduate of the National Institute of Design, she designed the prototype. This is now being used by 70 families belonging to the tribes of Soliga, Betta Kurumba and Panya.

The method is simple. A steel frame, in the shape of an elephant, is made -- the curved back, the long trunk and the thick legs. Then they cut the bushes. Thereafter, the sticks are boiled and shaved down. One layer of sticks is tied to the frame. Then a second layer is hammered in. “It's a very slow process,” says Tarsh. “Six people take one-and-a-half months to make one elephant. Varnish has been imported from the UK to provide an effective waterproofing.”

As this work goes on, Tarsh spends his time doing a study of the elephants, the character, and their interaction with human beings, as well as their historical contributions. “Alexander The Great ’s unstoppable army, which was conquering the whole world was stopped by 80 war elephants that belonged to King Porus’ army. This happened during the ‘Battle of the Hydaspes’ (320 BC) which took place on the river Jhelum,” says Tarsh. “Elephants helped the British to win the Second World War. They were used extensively to build roads by the Allied forces against Japan.”

Interestingly, elephants have a matriarchal society. Older males move in and out of different herds. They are polygamous. Temperaments vary from animal to animal. The senior ones are stable and peaceful. On the other hand, the younger ones are feisty and charge at people.

A wild elephant will rarely sleep in the open. “They prefer to sleep in an undisturbed location,” says Tarsh. “This is usually at 2 a.m., deep inside the forest and they lie down for four hours.” But in Gudalur, the elephants do not regard people as a threat. So they sleep anywhere.

Interestingly, elephants recognise each other by smell. They have the Jacob’s organ, which can process chemical signals. “If an elephant puts out dung or urine, another elephant can put it in its mouth and tell which individual it is,” says Tarsh. “So they are aware of the movements of each other in a herd.”

The good news is that there is a healthy population of 8000 in the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve. “We have dedicated our lives to ensure that they continue to thrive,” says Tarsh.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 12, 2019 22:21

February 10, 2019

In search of a dying girl

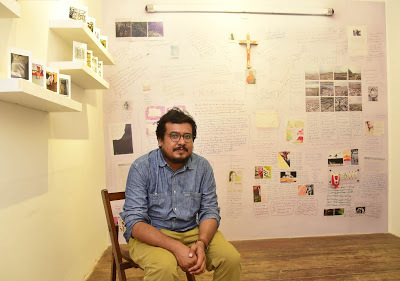

At the Kochi Muziris Biennale, documentary photographer Chandan Gomes focuses on a scrapbook of drawings which he came across at a hospice as well as people suffering from mental illness

Photos by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

At the Kochi Muziris Biennale, documentary photographer Chandan Gomes, a featured artist, points at the drawings of mountains and hills of a 10-year-old girl, Aini Hasina Bano. Right next to them, Chandan has put up photographs of actual mountains and hills which look the same.

And the story behind them is poignant. At the hospice within a hospital at Jaipur, Chandan saw Aini’s scrapbook on a shelf near a TV set. But when he inquired, he was told Aini had left. The hospital then told Chandan they would be unable to provide the address in order to protect the privacy of the patient.

“I was not disappointed because I was confident I could figure it out by talking to the nurses and attendants,” says Chandan, who had befriended a few because he had been spending several days in the hospital.

That was because Chandan had been commissioned to take photos of the patients, nurses, doctors, attenders and administrative personnel. The hospital was completing four decades and they were bringing out a coffee-table book.

But soon, Aini became an obsession. Whenever he found time, Chandan began travelling to the mountains and took shots similar to the ones that Aini had drawn. “The idea was simple,” he says. “Someday I would give Aini the book, with my photographs pasted next to her drawings, and maybe even sponsor a small trip to the mountains, which she had not seen in real life..”

But the search for Aini proved difficult. A young nurse gave four leads, three of which turned out to be false.

But the fourth led to a village called Baran in Rajasthan. Chandan, who is based in Delhi, went by bus. In the town, he managed to trace the girl’s uncle, Shaukat. “He told me the painful news that Aini had passed away,” says Chandan.

But now Chandan wanted closure by meeting the father, Anwar. But Shaukat only parted with the information about his brother’s whereabouts after he was paid some money.

Anwar was working in Narela, which is on the outskirts of Delhi. Chandan set out in September, 2013 to meet him and managed to locate him in a shanty. It had a crumbling roof and bare walls.

The first meeting was a disaster. “I was judging him by thinking, ‘how could he have let his daughter die?’,” says Chandan. “I did not understand that poor people have no choice. They cannot afford health care. They don’t have an education so they don’t even know their rights. They are at the mercy of the system. We had a tense conversation.”

At the second meeting, a week later, Chandan shared his meal: mutton curry and rotis. That eased the discomfort between the two.

Feeling that Chandan had accepted him, Anwar gave his daughter’s dolls, photographs and crayons to the photographer. “Aini suffered from a rare blood disorder,” says Chandan. “It was an expensive treatment. Even a lot of middle-class people would have struggled.”

But Anwar was going through a visible agony as he recounted his helplessness of not being able to save his daughter. “His pain became so unbearable that he began drinking heavily, to numb himself,” says Chandan. “His wife took their small son, and left because she was also angry with Anwar for not preventing Aini’s death.”

Chandan shook his head and says, “This experience taught me that there is so much more suffering in this world than what you are going through. Like, I would fret if there was no electricity in the house for five hours. I felt very small in front of Anwar. Too many lives are lost in this casual and brutal manner in India.”

Another series, placed next to Aini, begins with a haiku by the 17th-century Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa: ‘In this world; we walk on the roof of hell; gazing at flowers.’

The photos are of people who are going through a mental illness. “What is going on in the mind is never visible,” says Chandan. There is an image of a woman with her mouth open who is suffering from dementia. Another is of a baby who is just two days old. “Babies don’t have a language to express themselves, so I wanted to show the expressions,” says Chandan, who is the first Indian to have a solo show, after a decade, in July, 2018, at the prestigious Rencontres d’Arles Photo Festival in France.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 10, 2019 22:19

A Gem in the making

Executive Director Peter Lugg speaks about the new GEMS Modern Academy at Smart City, Kochi, one of the few schools in Kerala which offer the International Baccalaureate curriculum

Pics: Peter Lugg; a view of the school

By Shevlin Sebastian

One morning, Peter Lugg, the Executive Director of the GEMS Modern Academy at Smart City, Kochi got a call. It was from IT professional Anish George (name changed) who was calling from Mangalore.

Anish’s two children, Mark, 7, and David, 5, had been studying at Gems. But when the parents relocated, for better salary and other benefits, they had to put the boys in a new school. But it was clear to Anish and his wife Geetha that their children were unhappy. They were not enjoying school. So Anish called Peter and wondered what to do.

“Look, your children should be the focus of your life,” said Peter. Anish understood immediately and amazingly, unlike most Indian parents, they returned to Kochi so that the children could study in a school they liked.

“Happiness is a huge factor in a child’s life,” says Peter, who is of British-origin. “Because if a child is happy, he or she learns easily.”

One reason why the children love Gems is that the teaching is very different. Suppose, one day, the students are studying about volcanoes. In Gems, there will be different lines of enquiry, across several subjects. In geography, they will look at the different types of volcanoes. In history, they will study volcanic eruptions over the decades. In physics, they will look at the force of a volcanic eruption, and how its force and energy can be harnessed.

“We will get them to answer social questions: How many people are displaced during a volcanic eruption, and where do they go?” says Peter. “Why do they settle near volcanoes in the first place? Is the soil rich? How long have the people been living there?” There will be an art class where paintings on volcanoes will be done. In English class, students will write poems on volcanoes.

“What we want to impress upon our students is that each discipline is inter-related,” says Peter.

Interestingly, the boys are taught differently from the girls. “We know the boys prefer kinesthetic learning (learning through physical activity),” says Peter. “If a boy is 13 years old, his normal concentration level is 13 minutes. And so after 13 minutes of just teacher talk, they will tune off and start thinking about other things. So the teacher immediately changes the focus. He or she might take them outside and ask them to bounce a ball. It's called a breakout and then the students are brought back in, and the concentration levels become high once again.”

As for the girls, they are happy learning visually and orally, but they also have lapses in concentration. “So the teachers will do something different,” says Peter.

The Gems Modern Academy, set in an 8.3-acre campus, offers an International Baccalaureate syllabus as well as the IGCSE and ICSE curriculum. Thus far, there are classes from pre-KG to Class 6. Each class will have a maximum of 25 students.

From June onwards, Class seven will be added. And following that, every year, a new class will be added, till Class 12.

The facilities include dance and art studios, a medical facility, libraries, IT suites, science labs, and two swimming pools. “One will be 25 metres long and the other is a children’s pool,” says Peter. “There will be a multipurpose sports hall that will be ready soon, as well as a two-level dining hall.”

The school is part of the Gems Education Group which runs 70 schools in 12 countries. Asked why Gems has come to Kochi, Peter says, “Our chairman Sunny Varkey is from Kerala. He realised that Kochi, along with Smart City, is an attractive proposition for an international school. Kerala has many CBSE and ICSC schools, so there is space for a school that is international in flavour.”

A unique concept is the easy access of parents to the school. “They are welcome to come in anytime they want and can sit in on any class,” says Peter. “It's their child. This is their school. They have given their ‘gems’ to us. So, they have every right to see what is happening in the classroom. Why should I block them? Parents are our partners. They can watch their children roller skating. And if they want, they can bring their own pair, and skate with the children.”

Parents, indeed, are satisfied. Says entrepreneur Amit Sarkar, father of six-year-old son Vedaant, “The curriculum is a class apart. They teach in an unique way and avoid the . blackboard. My son is learning words through the phonetic way. I am very happy with the school.”

-------

The Indian link

Executive Director Peter Lugg of the GEMS Modern Academy, who is of British origin, has an Indian connection. His mother is half-Scottish and half-Indian. When she told Peter, who was living in London, to spend one year in India, Peter enrolled at St. Stephen’s College in Delhi. “The moment I landed in India I felt at home,” he says. “Soon I fell in love with the place.”

That got cemented when Peter married an Indian woman. Some of the places he has worked in include as an English lecturer in Delhi University, Woodstock school in Mussoorie, and the American school at Kodaikanal. Thereafter, Peter spent many years in West Asia: the Cambridge International School in Dubai as well as the Gems Cambridge High School in Abu Dhabi.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Kozhikode)

Published on February 10, 2019 22:03