Chris Thorndycroft's Blog, page 5

August 20, 2021

Fictional Feasts: A Medieval Trencher

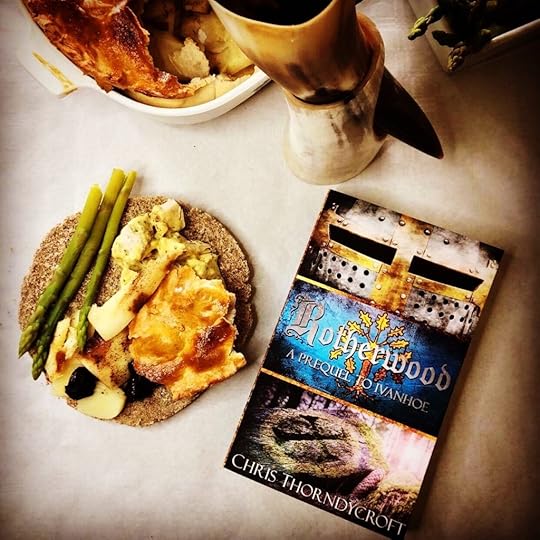

To celebrate the release of my new book Rotherwood: a Prequel to Ivanhoe, I made something that I’ve been wanting to try for a long time. A medieval trencher!

The nature of medieval meals was usually a collection of dishes from which the diners would help themselves similar to Tapas today. The diners would pile up their portions on trenchers; flat, round loaves of bread that served as plates. The bread would soak up the juices from the food and, according to some, would be given away to either the dogs or the poor at the end of the meal. It was considered rather bad manners to pick at or eat your trencher.

Trenchers would have been made of quite coarse bread (unrefined flour being cheaper) and may have been left to go stale for a few days so as to be dryer and more rigid. There’s no specific recipe for trencher bread but a good reconstruction can be found at Max Miller’s Tasting History channel. I’ve never made such rough bread before and kneading it was hard going. It went rock hard (even before I let it go stale) but after much sawing with a bread knife, I was able to separate it into two passable trenchers.

But what about some dishes to go with it? Medieval cuisine is a fascinating and deeply varied topic. Surviving recipes only go back as far as the 13th and 14 centuries and are notoriously vague when it comes to quantities and cooking times. There have been some excellent attempts at reconstructing some of these collected at the Medieval Cookery website where you can sort recipes by country and century. Unfortunately, nothing dates as far back as the late 12th century (when Rotherwood is set) but food and cooking techniques evolved slower in the middle ages than in later centuries so I went for a 15th century English ‘Henne in Bokenade’ (stewed chicken in sauce) and a 14th century French Parsnip Pie.

I used a simple hot water crust recipe for the parsnip pie and substituted the figs for prunes. The spices gave it quite a Christmassy flavour and the parsnips made it fairly sweet, giving one the idea of how people added sweetness to their diet before the importation of sugar. The stewed chicken was a real surprise, tasty, creamy and passable on any modern dining table. My sauce was quite thick but, as it is thickened with eggs, you can choose how thick you want it. Just make sure to temper the eggs first or you’ll end up with scrambled eggs and chicken!

I boiled up some asparagus just to complete things (there are some recipes for that on Medieval Cookery too) and served it all up on a trencher. This is only a small selection of what would have been a vast array of dishes at a medieval feast but at least it gives us some idea of what a meal would have been like in a well-to-do household (such as Rotherwood Hall or Sheffield Castle) in post-conquest England.

Rotherwood: A Prequel to Ivanhoe tells the story of Wilfred of Ivanhoe, the disinherited knight, who fights for honour and love under the banner of Richard the Lionheart. Get your copy here!

Rotherwood: A Prequel to Ivanhoe tells the story of Wilfred of Ivanhoe, the disinherited knight, who fights for honour and love under the banner of Richard the Lionheart. Get your copy here!

July 10, 2021

Cover reveal!

My 9th historical novel is now available for pre-order and here is the cover!

Wilfred of Ivanhoe – the disinherited knight – fights for honour and love under the banner of Richard the Lionheart in this thrilling medieval action-adventure which reconstructs the events leading into Walter Scott’s seminal historical novel ‘Ivanhoe’.

England, 1191. Disinherited for loving the Lady Rowena, young Wilfred of Ivanhoe joins King Richard the Lionheart’s crusade to reclaim Jerusalem. But there are hard choices awaiting Wilfred in the Holy Land where innocence is lost and loyalties are divided. While facing war, disease and treason, Wilfred realises that he must also fight for his very soul before he can return home to his beloved Rowena.

Meanwhile, back in England, the machinations of the king’s brother to steal the throne leave the country devastated by corruption and crippling taxes. Rowena of Rotherwood is determined to do something to ease the suffering of the poor and she finds an unexpected ally in the form of a nobleman-turned-outlaw who goes by the alias ‘Locksley’ …

May 31, 2021

The Audiobook of ‘A Brother’s Oath’ is Now Available!

A Brother’s Oath is now available from Audible! Narrated by professional singer, songwriter and actor Guy Barnes, this explosive production brings to life the 5th century and features a host of characters including pirates, warlords, kings and queens, in the earliest chapter of England’s history!

Get your copy HERE!

December 20, 2020

Food and Fiction: Christmas Special – Medieval Mince Pie

Mince pies – those small, fruity tarts – are part and parcel of the traditional British Christmas. But their original form, way back in the middle ages, was really quite different. They were big, they were savory and they contained actual meat. Various theories as to their origin point to returning crusaders who brought back exotic spices as well as methods of cooking meat and fruit together. A mince pie wasn’t strictly a Christmas dish but, due to exotic fruit and spices being so costly, it was the sort of thing only made for special occasions and, as such, became associated with Christmas.

I already took a stab at a Tudor recipe for a large mince meat pie but, after finding an even older one (dating to 1430), I wanted try it out. This one uses pork rather than beef and, due to pork being more fatty, requires no suet. It also includes egg yolks, red wine, dates and currants. The spices used are cloves, nutmeg and ginger. I have to say, I prefer this version. It’s far less greasy and has more in common with the modern pork pie, albeit with the addition of festive fruits and spices.

The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice is an anthology of short fantasy stories that explore some of the world’s oldest Christmas traditions from Neolithic Britain to Ancient Rome, puritan England, Spain, New York and beyond. All proceeds are donated to the charity Save the Children UK. Get your copy HERE!

November 16, 2020

Food and Fiction: Guest Post – Club Sandwich and Vanilla Milkshake

This is a guest post by P. J. Thorndyke, a writer of steampunk, horror, fantasy and classic pulp adventure. You can follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram or check out his blog.

The American diner is indelibly linked to the 1950s. Of course, diners go way back, evolving from the lunch wagons of the 19th century, but it was really in America’s post-war economic prosperity that the diner blossomed against the backdrop of booming suburbs and soaring production of automobiles. My newest book, Invasion of the Brain Tentacle, is an homage to the alien invasion and teenage delinquency B movies of the 1950s and what better way to celebrate its release than with a classic diner meal?

The club sandwich dates back to at least 1889 and, as with the Banana Split, there are two competing establishments for its invention, in this case the Union Club of New York City and the Saratoga Club in Saratoga Springs, New York. Recipes vary but generally agree on chicken (or turkey) with ham between toasted slices of bread. It is unknown when the sandwich evolved into its popular triple-decker form with the addition of a third slice, but that’s how it appeared on the menus of many diners and restaurants by the 1950s. By this time the club sandwich had also begun to merge with the BLT (bacon, lettuce and tomato) with a recipe for just such a combination in the 1903 Good Housekeeping Everyday Cook Book including the staples of mayonnaise and turkey.

Before the mass availability of electric blenders and refrigerators, milkshakes were hand mixed and involved ice cubes, milk, sugar and flavorings. By the 1950s, diners, lunch counters and drugstores were using automated, chilled mixing machines to turn out the frothy mixtures of milk and ice cream much beloved by teenagers. The other soda fountain favorite, the ‘malted’ or ‘malt’ was made famous by Walgreens in the 1920s and included the addition of malted milk powder.

A club BLT and a vanilla milkshake makes for a surprisingly filling and incredibly tasty lunch. It has a great retro appeal and is very easy to throw together.

[image error][image error][image error]

[image error]

Invasion of the Brain Tentacle is a standalone sci-fi thriller set in 1957 and inspired by alien invasion and juvenile delinquent B movies of the 1950s.

October 29, 2020

Food and Fiction: Guest Post – Banana Split

This is a guest post by P. J. Thorndyke, a writer of steampunk, horror, fantasy and classic pulp adventure. You can follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram or check out his blog.

I’ve always been fascinated by the American diner. There is something culturally unique about them; the vibrant colors, the chrome and of course, the food. In my book Curse of the Blood Fiends, there is at least one scene set in a 1940s diner and I really wanted to explore some of the food that might have been served at such an establishment.

The banana split dates back to the era of the 19th century soda fountain where cold drinks and ice cream were used to attract customers to pharmacies and department stores. Both Pennsylvania and Ohio lay claim to the invention of the traditional banana split as we know it (1904 and 1907 respectively) and even hold annual festivals in honor of the dish. Whatever its origins, it went on to enjoy massive popularity as America entered the age of the automobile, appearing on the menus of diners, drive-ins and ice cream parlors across the country.

It’s a simple dish with many variations but the classic banana split is as follows; 1 banana, split lengthwise, with 3 scoops of ice cream (vanilla, chocolate and strawberry), drizzled with sauces (chocolate, strawberry and/or pineapple) and topped with whipped cream, chopped peanuts and maraschino cherries.

It’s a delicious mixture of flavors and textures. I immediately had to make a second one as the one in the picture was instantly devoured by my kids.

[image error]

[image error]

Curse of the Blood Fiends is a standalone mystery-horror novel set in 1940s Los Angeles and is inspired by Universal monster movies and Film Noir. Order it here!

October 25, 2020

Food and Fiction: Halloween Special! – Pumpkin Pie

Pumpkin pie is a thanksgiving staple in American households but it also makes a pretty great dish for Halloween and even gets a mention in that spooky seasonal classic, Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow;

“On all sides he beheld vast store of apples; some hanging in oppressive opulence on the trees; some gathered into baskets and barrels for the market; others heaped up in rich piles for the cider-press. Farther on he beheld great fields of Indian corn, with its golden ears peeping from their leafy coverts, and holding out the promise of cakes and hasty-pudding; and the yellow pumpkins lying beneath them, turning up their fair round bellies to the sun, and giving ample prospects of the most luxurious of pies…”

One thing Washington Irving was great at was describing food. I can practically taste the spread put on by old Baltus Van Tassel at the fateful harvest party Ichabod Crane attends.

“And then there were apple pies, and peach pies, and pumpkin pies; besides slices of ham and smoked beef; and moreover delectable dishes of preserved plums, and peaches, and pears, and quinces; not to mention broiled shad and roasted chickens; together with bowls of milk and cream, all mingled higgledy-piggledy…”

Early methods of making pumpkin pie involved frying battered slices of pumpkin and apple and baking them in a pie crust, much like an apple pie. Some recipes even call for a savory soup served in an actual pumpkin. These days, a pumpkin pie is usually a sweet custard in a crust much like a flan or a quiche. The earliest published recipe for pumpkin pie appears in American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons, the first known cookbook written by an American. It was printed in 1796 (six years after The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is set) and calls for “One quart of milk, 1 pint pompkin, 4 eggs, molasses, allspice and ginger in a crust, bake 1 hour.”

These days you can buy canned pumpkin but, in the spirit of authenticity, I opted for fresh pumpkin roasted until soft and bubbling. There are no measurements for the molasses and spices in Simmons’s recipe so I just went with what I felt was enough, although Simmons must have made some whopping pies because the mixture was enough to fill two 9-inch pie dishes. I made the pastry from scratch, following an excellent recipe from Once Upon a Chef.

[image error][image error][image error][image error]

This was a very simple recipe as far as pumpkin pies go. No cinnamon, vanilla or nutmeg. Just molasses and all spice and that was just enough flavor. It goes to show that the old recipes really do hold up.

[image error]

Dreams of Dark Lands: 13 Tales of Terror is available from Amazon in print and as an Ebook.

Click Here for more Fictional Feasts!

May 24, 2020

Fictional Feasts: Roman Pork with Cumin in Wine

This dish is listed in Apicus (a collection of Roman recipes) as Aper Ita Conditur meaning ‘seasoned wild boar’. Wild boar being a little hard to get hold of in my neck of the woods, I’ve opted for a couple of pork loins instead. Apicus is thought to date to the 1st century A.D. and is generally geared towards the higher classes of Roman society, including some rather exotic ingredients like flamingo.

In my novel Sign of the White Foal, military men like Arthur would have been used to fairly coarse fare when on campaign, but I wanted to create something that he might have been treated to as the guest of some Romano-British lord keen to secure his support against Saxon raiders.

The original recipe reads;

WILD BOAR IS PREPARED THUS;

IT IS CLEANED; SPRINKLED WITH SALT AND CRUSHED CUMIN AND THUS LEFT. THE NEXT DAY IT IS PUT INTO THE OVEN; WHEN DONE SEASON WITH CRUSHED PEPPER. A SAUCE FOR BOAR: HONEY, BROTH, REDUCED WINE, RAISIN WINE. (Project Gutenberg)

I’ve found that a lot of these old recipe books are a little light on information like quantities and cooking times meaning some guesswork is required. A good reconstruction of this recipe can be found at The Romans in Britain which is a great resource for everything about Roman cuisine. I replaced myrtle or juniper berries with rosemary. It’s not too clear when rosemary became naturalised in Britain – it may have come with the Romans or it may have been introduced by 8th century monks – but on the basis of flavour, it is a common enough substitute.

[image error]

I wanted to make this into a meal for my family, so I found a good reconstructive recipe for Roman Bread (as well as a great blog post about it) at Tavola Mediterranea. This type of bread is called Panis Quadratus due to the four cuts across its diameter resulting in eight sections. A popular theory concerning the deep groove running around its edge is that these loaves were bound with string during their rising and baking. The purpose of the string may have been to hang them up in the shop or as a handy way for customers to carry them home.

[image error][image error]

But what about vegetables? Coquinaria has some interesting things to say about broccoli and, as that is one of the few vegetables my kids will actually eat, Roman style broccoli it is! I dressed it with toasted cumin seeds, olive oil, salt and wine.

Overall, not a bad meal. The pork went a little dry so I’d watch the cooking time on that and the bread was a bit on the heavy side. I don’t know how heavy Roman bread was but perhaps it could have done with more kneading.

[image error]

Sign of the White Foal is the first book in the Arthur of the Cymry trilogy; a retelling of the Arthurian legend in post-Roman Britain.

January 12, 2020

The Wait is Over!

Happy New Year! I hope 2020 is off to as good a start for all of you as it is for me. I’m thrilled to announce that the final volume in my Arthur of the Cymry trilogy is now available for pre-order from Amazon! The release date is 1st of February.

This has been a mammoth project for me that started more than 10 years ago. I always wanted to write a King Arthur trilogy and, after getting sidetracked by the backstory (which resulted in the Hengest and Horsa trilogy), I am over the moon to finally publish the epic conclusion to Arthur’s story. Field of the Black Raven will also be available in paperback although only the eBook is up for pre-order. I hope you all check it out!

The death of an era. The Birth of a legend.

The Saxons are defeated. The British kingdoms work towards a future of peace and for Arthur, it is time to return home to the mountains of Venedotia. But an even worse enemy wreaks death in his absence; the pestilence, a black hand that snuffs out life leaving only corpses in its wake.

With the death of the Pendraig Cadwallon, Arthur comes home to find a crisis of succession. Many good men are drawn into a tangled web of lies including Arthur’s nephew and adopted son Medraut. Finding themselves on opposite sides of a war not of their making, they race towards a devastating confrontation. It is on the banks of the River Camlan that many journeys come to an end and history becomes legend.

November 16, 2019

Searching for Dragons – Romano-British Depictions of the Dragon

When designing the cover for Banner of the Dragon – book 2 of my Arthur of the Cymry trilogy – I was alarmed at how difficult it was to find any depictions of dragons in early British art. Surely dragons were a thing in ancient Britain, right? After all, the Welsh flag has a dragon on it and the very name ‘Pendragon’ comes from the Welsh ‘Pendraig’ meaning head or chief dragon (dragon being a poetic stand-in for warrior). Nevertheless, I was coming up decidedly short in my search for an authentic British or Romano-British depiction of a dragon.

The red dragon did not become a symbol of the British until the 9th century Historia Brittonum which likened the ongoing conflict between the Saxons and the Britons as a battle between two dragons; the former white and the latter red. Henry Tudor used the red dragon as his flag in 1485 as a direct reference to this tale, and it became forever associated with Wales. As for the epithet ‘Pendragon’, that was a name bestowed upon Arthur’s father Uther and Arthur himself is never referred to as Pendragon outside of modern fiction. The main reason that Pendragon couldn’t have been passed on to Arthur as a family name is that the early Welsh used patronyms – they took their father’s name as a surname and were either ‘mab’ (son of) or ‘ferch’ (daughter of). So if Arthur was the son of Uther Pendragon, he would be simply ‘Arthur mab Uther’.

The word ‘dragon’ seems to have entered the British language via the Romans who had a military standard called the ‘draco’. This may have been introduced into the Roman army by Sarmatian or Scythian cavalry units. Essentially it was a windsock attached to a metal dragon’s head which made a hissing sound when inflated by the wind.

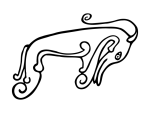

I trawled through images of Celtic art going way back to pre-Roman times to see if there were any dragons. The only thing I found that came close was the Pictish ‘beast’. It’s a bit of a weird creature and some even think it represents a dolphin. But then, a fellow member of a Facebook group pointed me in the direction of a ‘dragon brooch’ kept in the British Museum. This was much more promising.

This dragonesque brooch is typically Romano-British and dates from the 1st or 2nd century. At last I had finally found a British image of a dragon dating to the time period directly before the Arthurian age. It’s design is a fascinating fusion of the Roman and the Celtic and perfectly symbolises Arthur himself. I only needed it as a small detail for my book cover but am pleased I was able to use something authentic that has some meaning to the story.

Banner of the Red Dragon is the second book in the Arthur of the Cymry series and tells the story of how Arthur, a young warrior, becomes ‘penteulu’ of Venedotia and wins his decisive victory over the Saxons at the Battle of Badon.