Chris Thorndycroft's Blog, page 3

November 11, 2024

Historical Fiction Deals for November!

Just a heads up to let you know that my book A Brother’s Oath (Book 1 in the Hengest and Horsa trilogy) is only $0.99/£0.99 all November as part of the Fall Historical Fiction book promo! Check out this and tons of other HF deals and grab a bargain while they’re cheap!

October 7, 2024

New Novella!

I have recently written a new novella which is currently free to subscribers of my mailing list. It’s called A Blade for the Heathen and is set in pre-Viking Denmark, a few years before the start of my Hengest and Horsa trilogy.

If you’d like a copy, you can grab one as part of this fantastic group promo featuring tons of action-adventure books of all genres which you can get for free! Please check out some of the other titles in the promo, as I’m sure you’ll find some great new books to add to your reading pile!

May 12, 2024

Research Nuggets: Dumbarton

One of the locations in my upcoming historical series is Dumbarton, or rather, the hill fort that once crowned the striking Dumbarton Rock on the north bank of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland.

Dave Hitchborne / Dumbarton Castle / CC BY-SA 2.0

Dave Hitchborne / Dumbarton Castle / CC BY-SA 2.0A volcanic plug of basalt, Dumbarton Rock forms two peaks, the highest of which rises to 75 meters (240 feet). During the Roman and post-Roman period, the rock was the capital of a British kingdom called Alt Clut, or Alcluith (meaning ‘Rock of the Clyde’). Beyond Hadrian’s Wall, the Britons of Alt Clut were independent from Roman rule and were a Brythonic-speaking people (Brythonic being the ancestral language of Welsh). One of their kings – Coroticus of the mid-5th century – seems to have been chastised by St. Patrick for selling Christians into slavery and some of his soldiers were excommunicated, indicating that this part of Britain had been Christianised by the post-Roman period.

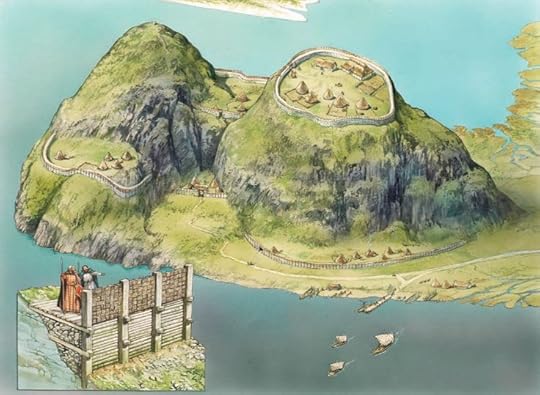

Alt Clut in 870 A.D. by Peter Dennis for the Osprey book Strongholds of the Picts

Alt Clut in 870 A.D. by Peter Dennis for the Osprey book Strongholds of the PictsAlt Clut was often threatened by Picts, Scots, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings throughout the early medieval period, and fell to a Norse-Gaelic army from Dublin in 870. After this point, Alt Clut became part of the Kingdom of Strathclyde (Ystrad Clut in Old Welsh). Meaning ‘broad valley of the Clyde’, Strathclyde was sometimes referred to as ‘Cumbria’ (which, along with ‘Cymry’ – the modern Welsh word for themselves – derives from the Brythonic word ‘kombrogi’ meaning ‘fellow countrymen’). Alt Clut itself came to be called Dumbarton via the Scots Gaelic word Dùn Breatann meaning ‘fort of the Britons’.

Ultimately, Strathclyde became part of the Gaelic-speaking Kingdom of Alba (an early version of the Kingdom of Scotland) in the 11th century which also swallowed up the Pictish kingdoms but that is well beyond the scope of my novels. Set in the late-4th and early-5th centuries, my trilogy deals with the end of Roman rule in Britain and how, particularly in the north, this upheaval payed a part in the formation of independent kingdoms.

May 5, 2024

‘Buccaneer’ now only 0.99p!

Great news! The first book in my Molucca Star Quartet has been selected by Amazon for a Kindle monthly deal. That means you can pick up the thrilling first installment in my saga of pirates and smugglers for just 99p for the rest of May 2024! (UK only, I’m afraid).

Buccaneer: The Early Life and Crimes of Philip Rake was a real passion project for me as I was infatuated with pirates as a child after seeing Disney’s Treasure Island (1950) and I had always wanted to write a rollicking pirate adventure story of my own. So, if you’re in the UK, check out the blurb and link below and grab your copy for only 99p and join the adventure!

Bristol, 1713. When Philip Rake, pickpocket, smuggler and scoundrel is arrested and thrown in jail, he assumes he has a short walk to the gallows. But his father, a wealthy merchant who has remained a figure of mystery throughout his life, throws him a lifeline; become an indentured man on an expedition to the East Indies led by his friend, Woodes Rogers.

Woodes Rogers is looking for Libertatia – the fabled pirate kingdom of the legendary buccaneer Henry Avery – and the hoard of treasure rumoured to be hidden there. But Philip wants his freedom and when he learns that there are men onboard who once sailed with Henry Avery and plan to take the treasure for themselves, he jumps ship and embarks upon a career of piracy.

Philip’s story takes him from the backstreets of Bristol to the sun-baked hills of Madagascar and on to the tropical islands of the Caribbean in a thrilling tale of adventure in which he rubs shoulders with some of the most notorious pirates of the age including Blackbeard, Charles Vane, Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Get your copy here!

April 14, 2024

The Attacotti: Cannibals in 4th Century Britain?

An interesting tidbit that came up while researching my next novel is a potential tribe of cannibals living in late Roman Britain.

The Attacotti are one of Britain’s more mysterious tribes as nobody is too sure exactly where they lived or if they were Britons, Picts, Scots or belonging to some other culture. They are first mentioned by the historian Ammianus in connection with the ‘barbarian conspiracy’ of 367 A.D. in which they, along with the Picts, Scots, Saxons and Franks, attacked Roman Britain in a possibly coordinated assault. The Attacotti certainly seem to have been regarded as a distinct people but they are mysteriously absent for much of Roman Britain’s subsequent recorded history.

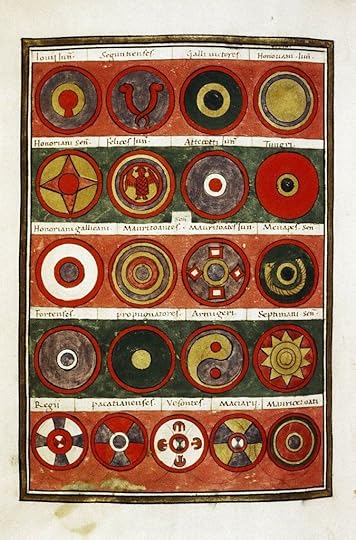

The next reference to them crops up in the Notitia Dignitatum, a document of the 4th to 5th century which details the military organisation and units of the late Roman Empire. This document mentions at least a couple of auxiliary infantry units which seem to be made up of Attacotti tribesmen; the Attacotti Honoriani Seniores, and the Attacoti Honoriani Juniores; the former making appearances in Gaul, and the latter in both Gaul and Italy.

Page from a medieval copy of the Notitia Dignitatum showing the shield designs of various units.

Page from a medieval copy of the Notitia Dignitatum showing the shield designs of various units.Barbarian warriors were often recruited into the military of the Roman Empire but we still don’t know anything else about the Attacotti. That leaves it to St. Jerome, an early priest and historian to give us his two cents in his late 4th century treatise, Against Jovinianus.

“Why should I speak of other nations when I myself, a youth on a visit to Gaul, heard that the Atticoti, a British tribe, eat human flesh, and that although they find herds of swine, and droves of large or small cattle in the woods, it is their custom to cut off the buttocks of the shepherds and the breasts of their women, and to regard them as the greatest delicacies?”

A pretty alarming claim about a people we know nothing else about. Were they cannibals or was this just Christian slander against a pagan barbarian people? We have little way of knowing as there are no other mentions of the Attacotti to either dispute or confirm St. Jerome’s claims. Everything else about them is pure speculation.

Several attempts have been made to link the Attacotti to the Irish ‘aithechthúatha’; a derogatory term for various low status tribes who paid tribute to the more powerful Irish tribes at the time, although the etymology for this is a little shaky. Irish settlers did indeed put down roots and build kingdoms in Britain at the end of Roman rule including the Scots, (‘Scotia’ being an old Roman word for Ireland) and the Attacotti may well have been one of these Gaelic-speaking groups who found a new home in Britain.

As for St. Jerome’s cannibalism claims, it is strange that nobody else mentioned such extraordinary behavior going on as late as the 4th century, and there are only minor indications that any Celtic peoples practiced cannibalism. The discovery of a bone deposit in a cave at Alveston, South Gloucestershire in 2001 (including a split human femur from which the bone marrow had been scraped out) was interpreted as evidence of cannibalistic activity at the beginning of Roman occupation in Britain. In addition to this, the Greek philosopher, geographer and historian Strabo claimed that the people of Irene (Ireland) were ‘man-eaters’, but, like the cave in Gloucestershire, that was back in the 1st century so perhaps St. Jerome was merely repeating old news.

March 8, 2024

Giving Anglo-Saxon poetry a go

What is an Anglo-Saxon story without a little alliterative verse? In my novel A Brother’s Oath (book 1 in the Hengest and Horsa Trilogy), I have some exposition given in the form of a poem written in the style of Beowulf. The scene is a smoky mead hall where Horsa and his companions have sought shelter for the night. As the marsh mist descends around the hall, the chieftain’s scop (a poet) tells them a creepy story about the ancient cult of the Wanes (Germanic fertility gods cognate with the Norse Vanir).

These lands hold a lake, lost to time,

Formed in the beginning, when the world was barely born.

Around its still depths the settlers dwelled,

Wane-worshippers they were, wiccan and wise,

And from whence they came none now know.

The mere-dweller was their matron; a goddess of guile,

A queen of the land from long distant legend,

In shadow-haunted woods was she worshipped,

And in moonlit circles, her slaves were sacrificed,

And blood ran red on the runestones to her name.

Her name was Gefion; a goddess of giving,

And in her image an idol, iridescent was made,

Of glittering gold, gleaming and smooth,

With eyes of jade and studded with gems,

No finer fashioned idol was ever forged.

Rome rose and fell and the rumours remained,

Of the Wane-goddess and her worshippers,

By the shores of the lake, in luxurious wealth,

Denying the new gods, no glory to them,

Of Woden and Frige, frightened were they not,

Nor of Thunor and Tiw, truth they already knew.

The Sons of Woden, heard whispers of the Wanes,

And set out with shields, and spears sharpened bright,

Of greed they thought, to gain glory for their gods,

And pillage and plunder, to fill their purses.

Red ran the lake, as the looters found victory,

Over the children of Gefion who were butchered and slain.

The golden statue was stolen away,

A goddess defeated and her devout left dead.

Around the idol, the ill-meant victors revelled,

Until mead and merriment, muddled their minds,

And they slept, strewn in the statue’s shadow.

But dawn broke over barbarous ruin,

The warriors’ corpses were cloven and clawed.

None had awoken during the slaughter, and the stolen statue,

Was stolen once more.

The women wept for Woden’s brave sons,

And the missing idol spoke of mischief and malice.

None knew who had slaughtered their stout sons,

And the hills hide their hideous secrets.

No names give the nighted fens,

And the forests feed no answers to the fearful.

Gefion and the Wanes are forgotten but by the few,

But some say they have seen strange sights on the moors,

Of troll-shapes in the mist, murderous and monstrous,

And strange lights beneath lakes at night,

In league with the lake-dweller they liken these things,

And the Wane-queen’s vengeance will never wilt,

Nor will the shape that haunts these lands.

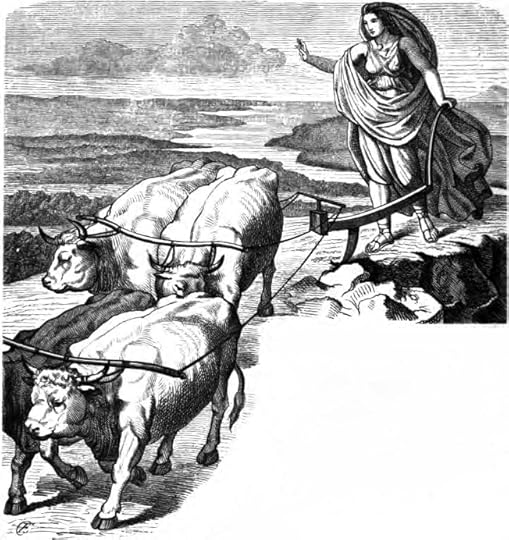

Gefjun Plows Zealand with her Oxen (1882) by Karl Ehrenberg

Gefjun Plows Zealand with her Oxen (1882) by Karl EhrenbergThe Roman historian Tacitus tells us of a goddess called Nerthus who was kept in a sacred grove on an island in the northern sea. Referred to as ‘Mother Earth’, Nerthus rode a wagon pulled by cows and traveled among the populace who feasted and made merry in her wake. The goddess (possibly represented by a statue) was then cleansed in a sacred lake and her slaves were then drowned.

Nerthus appears to be a Latinisation of Njorthr; a god of the sea attested to in later Norse literature. Why give a goddess a male name? One theory is that we are dealing with a set of twin deities akin to Freyr and Freyja (who were Vanir and the offspring of Njorthr according to Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda). Who then was the female counterpart to Nerthus? One candidate might be Gefion, a fertility goddess associated with ploughing whose name possibly means ‘the giving one’ and appears to be mentioned several times in Beowulf. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla both credit Gefion as creating the Danish island of Zealand by gouging out a piece of Sweden with her plough and dumping it into the sea. Some theories have interpreted the battle between Beowulf and Grendel’s mother in the famous Anglo-Saxon poem as an allegory for the overthrow of an older fertility cult by a younger cult of war gods represented by Woden, Thunor and their fellow ‘Ese’ (Aesir) who were known to have fought a war against the Wanes (Vanir).

October 28, 2023

Fictional Feasts: Venison Pasties

“They filled in wyne and made hem glad,

Under the levys smale,

And yete pastes of venyson,

That gode was with ale.“

– Robin Hood and the Monk

So celebrated Robin Hood and his gang in the medieval ballad Robin Hood and the Monk after they rescued him from jail and made off into the greenwood; a meal of ale and venison pasties and I can’t think of anything better on a cold autumn day!

But venison was a high status meat in the middle ages. William the Conqueror created royal forests where only the king and those he gave permission to could hunt deer. Governed by highly unpopular forest laws, these areas covered nearly a quarter of England and forbade the hunting of deer. Local lords were occasionally given permission to hunt, sometimes for a fee, but anybody else could be harshly punished. This meant that venison was an expensive meat, occasionally given as a gift or served at the table of a wealthy lord either roasted or in pies and pasties. The less privileged would never taste it. Unless of course, they were a poacher …

I threw together these simple venison pasties from some left over roast venison, a few era-appropriate spices or ‘poudre forte’ as it was known (ginger, cinnamon, cloves and pepper) and a recipe for basic shortcrust pastry.

It seems unlikely that Robin and his gang would be making pasties in the greenwood so one wonders where they got them from in Robin Hood and the Monk. Perhaps they swiped them from a lord’s table? Pasties were also a handy form of street food in the middle ages, sold at market stalls to be easily consumed on the go and have remained a popular part of English cuisine to this day, the best-known example being the ‘Cornish’ pasty.

Lords of the Greenwood is a retelling of the legend of Robin Hood, weaving real history with medieval ballad. Get your copy here!

October 23, 2023

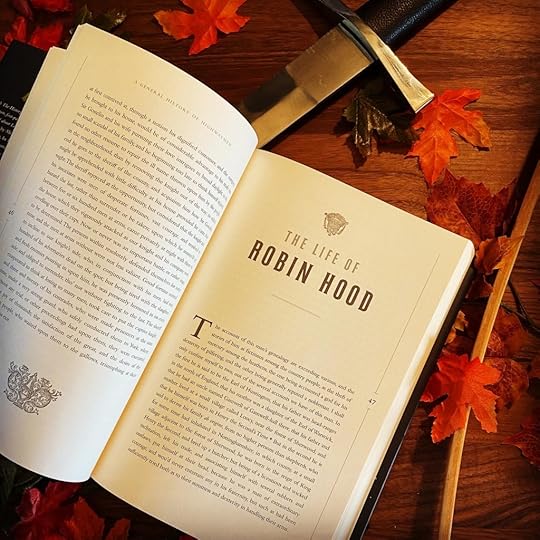

An 18th Century View of Robin Hood

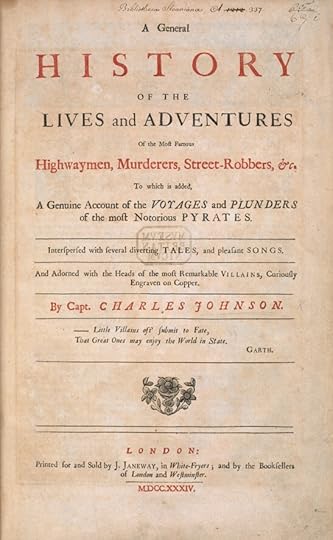

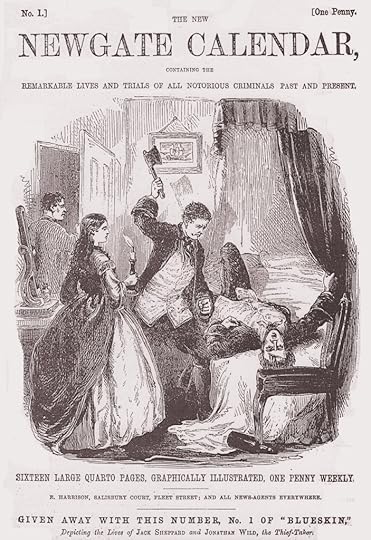

While researching my ‘Molucca Star’ quartet of novels concerning pirates and smugglers of the 18th century, I naturally read a lot of contemporary accounts of criminals found in the Newgate Calendar as well as Captain Charles Johnson’s influential 1724 book A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates. It was in Johnson’s followup book A General History of the Lives and Adventures of the Most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers & Street-Robbers that I found an interesting connection to a couple of my other novels, the ones about Robin Hood.

Charles Johnson shamelessly plundered an earlier book on highwaymen by Alexander Smith, published in 1714, mixing Smith’s accounts of various villains with his own accounts of famous pirates. One account he lifted from Smith’s book was a summary of the life of England’s famous outlaw, Robin Hood. It’s a strange inclusion to place a most likely fictional medieval outlaw among real-life villains and thieves like Moll Cutpurse and Blackbeard the pirate but there was a voracious appetite in the 18th century for accounts of criminals and their gruesome fates exemplified by the phenomenon of the ‘criminal biography’; lurid tales of men and women giving into idleness and embarking upon lives of sin and wickedness before meeting their ends, usually at the end of a rope. And, as Robin Hood is perhaps one of the most famous highwaymen of all time, it probably shouldn’t be too surprising that he also got the criminal biography treatment.

But, when viewing the famous outlaw through 18th century eyes, we see some stark differences to the Robin Hood of medieval ballads or the popular fiction of modern times. Johnson’s book places him in the reign of Henry II (1154 – 1189), earlier than the reign of Richard the Lionheart (1189 – 1199) of most modern books and films, and earlier still than the setting of the medieval ballads which is that of an unspecified King Edward (meaning somewhere between 1272 and 1377). The account also dispenses with the idea that Robin Hood was descended from the earls of Huntingdon (popularized by the Tudor playwright Anthony Munday). Instead, Robin is the offspring of poor shepherds in Nottinghamshire.

As in most criminal biographies of the time, Robin ditches his honest trade and throws in his lot with villains. Johnson then gives a brief selection of adventures similar to what we get in the medieval ballads. such as Robin winning an archery tournament organised by the king and tricking the sheriff by selling meat at ridiculously low prices. Although it is mentioned that Robin robs the rich and gives to the poor, he comes across as a much more cold-blooded thug in Johnson’s account. The ballads have Robin entering in the service of the king upon meeting him. Johnson has him simply rob him.

William Stutely and Robin Hood from Captain Charles Johnson’s ‘Most Notorious Highwaymen’

William Stutely and Robin Hood from Captain Charles Johnson’s ‘Most Notorious Highwaymen’In the medieval ballads, Robin grows sick and goes to a priory at Kirklees to be bled by his cousin, the prioress. Through collusion with her lover, Sir Roger of Doncaster, the wicked prioress bleeds Robin to death. Johnson’s account of Robin’s death follows this to some extent with the important difference of him retiring to a monastery ‘struck with some remorse of conscience’. This is in keeping with the criminal biographies of the 18th century which were intended as morality tales to deter readers from following in the footsteps of their sinful subjects. Far from being a hero of the people, Robin feels guilt for his life of wickedness and is eventually punished for his crimes.

While Johnson’s account of the life of Robin Hood gives us nothing we might rely upon as historical evidence for the outlaw’s life (it was written far too late and Johnson was known for embellishing facts to a degree that they might as well be fiction), it is an interesting example of how the legend of Robin Hood changes with the retelling to suit its audiences.

And you can read my own accounts of Robin Hood in both Lords of the Greenwood and Rotherwood: A Prequel to Ivanhoe. Both available in print and for Kindle from Amazon.

September 2, 2023

‘Man of Fortune’ now available!

The next installment in the swashbuckling adventures of pirate Philip Rake is now available on Amazon! You can get it in print or for Kindle or, if you are in Kindle Unlimited, you can read it for free! Get your copy here!

August 8, 2023

‘Buccaneer: The Early Life and Crimes of Philip Rake’ Now Available!

My newest historical fiction novel – Buccanner: The Early Life and crimes of Philip Rake – is finally on sale from Amazon! It is available in print and for Kindle as well as being in Kindle Unlimited. You can get your copy here!