Chris Thorndycroft's Blog, page 2

April 17, 2025

The Year of the Three Emperors and the Fall of Roman Britain

This silver Roman coin called a ‘siliqua’ depicts Constantine III, Britain’s homegrown usurper, who stripped the island of the last of its troops in 407.

This silver Roman coin called a ‘siliqua’ depicts Constantine III, Britain’s homegrown usurper, who stripped the island of the last of its troops in 407.My next installment in the Dragon of the North trilogy – The Pictish Crown – is set during a tumultuous and fascinating period in which Britain went from being a frontier diocese of the Roman Empire to an independent island left open to invasion by barbarian peoples and squabbled over by petty tyrants. After four hundred years of occupation, Rome simply washed its hands of the troublesome island. How and why are questions that historians (and writers) have been puzzling over for centuries.

By the late 4th-century, Rome had been facing increasing troubles on the continent, necessitating the need to draw troops from Britain to defend other territories. Severely undermanned, Britain’s frontier defenses like Hadrian’s Wall and the the so-called Saxon Shore were vulnerable to attack. Coinage had also dried up, meaning the few troops in Britain hadn’t been paid in quite some time. For an island that had revolted several times under Roman rule, another rebellion seemed inevitable.

In 406, the military stationed in Britain took matters into their own hands and elected one of their own as emperor. This had happened before. In 383, Magnus Maximus, a high-ranking general, proclaimed himself emperor and marched on Gaul to legitimize his claim (creating yet another drain on Britain’s military resources). The rebellion of Maximus was a failure but that wasn’t about to stop the Britons from trying again. This new emperor was called Marcus and his reign was, by all accounts, short and unpopular. He didn’t even last a year before he was killed and replaced by one Gratian who, unlike previous usurpers was not a military man but a member of the urban aristocracy.

Perhaps the aim was to rectify trade and tax problems but, in the winter of 406, disaster happened. A confederation of Germanic barbarians consisting of the Vandals, the Alans and the Suebi crossed the River Rhine, Rome’s northern boundary on the continent, and entered the empire. Order in northern Gaul collapsed and Roman towns were looted and burned. This was frightening stuff for the island of Britain which had little in the way of troops to defend it. If the barbarians could march into Gaul unstopped, then they could easily cross over into Britain.

It was clearly decided that a military man was the way to go after all, which was bad news for Gratian who was summarily executed and replaced by a soldier called Constantine (Britain’s third usurper in less than a year). Constantine, it is said by the historian Orosius, was picked largely because he shared a name with Constantine the Great, one of Rome’s most fondly remembered emperors who had also come to power through a coup in Britain. This new Constantine certainly had the backing of the troops stationed in Britain who followed him into Gaul to fight the barbarians, hoping to stop them from reaching British shores.

Left undefended, the Romanised Britons had to fend off attacks from barbarians like the Saxons with no help from Rome.

Left undefended, the Romanised Britons had to fend off attacks from barbarians like the Saxons with no help from Rome.Britain was now almost wholly abandoned with no legions left to protect it. While Constantine fought for legitimacy on the continent, British shores were attacked by Saxons. Many Britons, angered at the failure of their homegrown emperor to protect them, staged yet another coup in either 409 or 410 and expelled Constantine’s officials, taking control of the island for themselves.

While Constantine was eventually recognised as co-emperor of the West by Emperor Honorius, he was betrayed by one of his own generals and eventually defeated and executed. But Rome was in no state to reclaim its wayward diocese. Emperor Honorius faced uprisings and barbarian invasions for the rest of his rule and the rule of his largely inept successor, Valentinian III, was dominated by civil wars and invasion by the Huns. 410 officially marks the end of Roman Britain.

What happened in Britain in the following centuries during the so-called ‘Dark Ages’ is tangled up in myth, with few and fragmentary sources. It was undoubtedly an age of invasion by Picts, Saxons and Gaels and a time of tyrants like the mysterious ‘Vortigern’ not to mention the great British hero Arthur. One other figure who rose to prominence during this time was Cunedag (or ‘Cunedda’) who defended what is now North Wales from the Gaels, thus founding the Kingdom of Gwynedd.

While Cunedag was a young soldier stationed on Hardian’s Wall in Defender of the Wall, book 2 finds him a king of his own tribe, though still wholly dedicated to protecting Britain as Rome’s control over the island slips away. The Pictish Crown will be published on April 30th and you can preorder your copy here!

April 15, 2025

The Pre Order for ‘The Pictish Crown’ is now live!

This second installment in the exciting legend of Cunedag sees Roman control over Britain crumble and the island’s tribal inhabitants struggle to survive without Rome’s protection.

If you haven’t already started this trilogy, then you can grab book 1 – Defender of the Wall – here! The Pictish Crown will hit stores in both print and for Kindle on April 30th! Here’s the blurb;

407 A.D.

Chaos sweeps the Roman Empire. The legions stationed in Britannia have elected their own emperor – Constantinus – who has vowed to safeguard the island’s interests. But when Constantinus takes all of Britannia’s military might with him to Gaul to legitimise his claim, the Britons are left open to attack by barbarians on all sides.

Meanwhile, the king of the most powerful Pictish tribe has died leaving a crisis of succession. Tribal quarrels and rivals for the crown plunge the north into civil war at the worst possible time. King Cunedag of the Votadini steps in to help unite the Picts under a single king. But is a high king of the Picts a good idea, and will he prove to be a friend or foe to the vulnerable Britons who have suddenly found themselves beyond Rome’s protection?

The Pictish Crown is the second part of a trilogy which tells the story of the legendary King Cunedag; a dark age warlord who went on to build the Kingdom of Gwynedd from the ashes of post-Roman Britain.

April 1, 2025

Some Historical Fiction Book Recommendations

Happy April! I hope spring is off to a good start with you. If you’re looking for some springtime historical fiction reads, then I’ve got you covered! Here are a couple of book promos I’m involved with which include a ton of HF recommendations. Do check them out and discover your next read!

March 4, 2025

It’s Publication Day for ‘Defender of the Wall’!

Today is the day my newest historical fiction novel – Defender of the Wall – lands! I’m currently writing book 3 in the trilogy, while simultaneously editing book 2, so expect much more to come in the following months!

In the meantime, I hope you grab a copy of Defender of the Wall and enjoy it and, if you do, please leave a review as that’s a massive help in attracting new readers! It’s in Kindle Unlimited, but you can pick up a print copy from most online booksellers like Barnes and Noble.

To celebrate publication day, I’m featured on a couple of book blogs you can check out. Tony Riches’ The Writing Desk has a short bit by me about how I came to write Defender of the Wall and there’s also an excerpt from the novel on What Cathy Read Next.

February 21, 2025

Cavalry Units of the Late Roman Empire

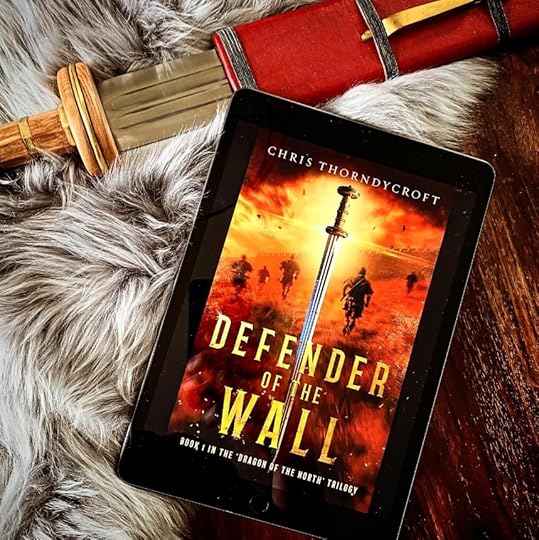

My newest novel, Defender of the Wall, is set at the end of Roman Britain and deals with the Roman military, specifically, the cavalry units stationed on Hadrian’s Wall. Naturally, there was a lot of terminology to learn regarding ranks and titles, not to mention researching how these units lived and operated. So, in light of my book’s upcoming release (March 4!), I thought I’d share some of my research here.

My main character, Cunedag, is a decurion in the Roman army. This was a cavalry officer in charge of a turma, which is a squadron of about 30 or 32 men. Turmae were part of a larger unit called an ala. There were two types of alae, one with 16 turmae which was called an ala quingenaria and one with 24 turmae which was called an ala milliaria.

Literally meaning a ‘wing’, alae were elite mounted auxiliary units who would fight on the flanks of the infantry during battle. Another form of cavalry unit was the equites cohortales which was attached to an infantry unit and were likely just mounted infantry with poorer quality horses and equipment. This provided an opportunity for a good bit of friendly rivalry and banter between Cunedag’s unit and other soldiers in my novel whom they consider inferior.

Alae were under the command of a praefectus alae (or ‘prefect’) with each turma commanded by a decurion like Cunedag. Two under-officers would aid the decurion; the duplicarius (who received double pay), and the sesquiplicarius (who received pay and a half). Each turma also had a standard bearer such as a draconarius so-called because of the ‘draco’ dragon standard which was adopted from eastern peoples like the Dacians and Sarmatians and became the standard for cavalry units of the late Empire. The draco consisted of a hollow bronze head to which was attached a long fabric sleeve much like a modern windsock. When galloping, air would rush through the mouth of the bronze head and inflate the sock, while creating a whistling sound to terrify the enemy.

Reenactment of Draconarius at the Roman Festival 2013, Augusta Raurica (Codrin. B)

Reenactment of Draconarius at the Roman Festival 2013, Augusta Raurica (Codrin. B)Roman cavalrymen of the late Empire were armed with a spear and a throwing javelin as well as a spatha which was a longer sword than the gladius used by the infantry, enabling them to reach enemies on the ground from their saddles. Stirrups were almost unknown in the Roman cavalry, with saddles having 4 horns which would keep the rider in place. Cavalrymen carried oval or hexagonal shields which were lighter than the rectangular scutum carried by the infantry.

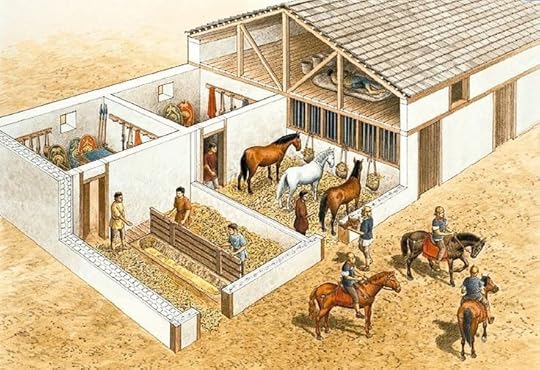

Cavalry played an important part in defending Hadrian’s Wall, with an estimated third of the Wall’s garrison being mounted units. Cavalry forts like Cilurnum (Chesters near the village of Walwick) projected out from the wall with three of its gates on the northern side to allow rapid deployment of its troops. Inscriptions show that the ala II Asturum (Cunedag’s unit in my book) were stationed at Cilurnum from at least the late-2nd century.

A reconstruction of the fort and civilian settlement at Chesters as they may have appeared in about AD 200.

A reconstruction of the fort and civilian settlement at Chesters as they may have appeared in about AD 200.© Historic England (illustration by Mikko Kriek)

Cilurnum guarded the bridge which carried the wall over the River Tyne which flowed between its stone legs. A vicus (a civilian settlement) lay clustered around its southern walls and there was an elaborate bath house on the west bank of the river. This was later abandoned in favour of a bath complex in the praetorium (the commanding officer’s residence) within the fort.

Cavalry units were housed in a long row of barrack blocks with each cell housing three men and their horses. A covered urine trench ran the length of the section for the horses, while the men slept on bunks in the rear room. Living and sleeping with their mounts no doubt forged a close bond between the men and their horses, not to mention warmth provided by the animals during cold winter months.

Auxiliary cavalry barrack block (from Roman Auxiliary Forts 27 BC – AD 378, Osprey Publishing)

Auxiliary cavalry barrack block (from Roman Auxiliary Forts 27 BC – AD 378, Osprey Publishing)Preorder Defender of the Wall here!

February 17, 2025

‘Defender of the Wall’ Pre-Order Now Live!

Here’s the cover of my next historical fiction novel – Defender of the Wall – and it’s now available to pre-order from Amazon! Publication day is set for March 4th and a print version will also be available from most online platforms on that date.

I’m thrilled with the cover for this one and am currently writing book 3 in the trilogy, with book two being edited as of writing. The Dragon of the North trilogy is going to be a thrilling saga of one man’s journey from political child hostage, to Roman cavalry officer, to king of a free nation!

Check out the blurb;

Britain, 390 A.D.

As a barbarian prince fostered by a Roman family below Hadrian’s Wall, Cunedag’s loyalties have always been conflicted. His own people despise the Romans with a passion, yet he has grown to manhood among them and is now a cavalry officer stationed on the Wall.

But Rome’s grip on Britain is slipping and the north, sensing weakness, explodes in all-out rebellion. As the Picts sweep down to harry the frontier, the province marshals its forces to fight back. And Cunedag is presented with a difficult choice; continue to defend Rome or rule his people as a free king.

A Roman military novel packed with action and adventure, Defender of the Wall is the first part of a thrilling historical fiction trilogy which tells the story of the legendary King Cunedag; a dark age warlord who went on to build the Kingdom of Gwynedd from the ashes of post-Roman Britain.

January 17, 2025

Who was Cunedda?

As book 1 in my next historical fiction trilogy is nearing publication, I can finally tell you a bit more about it! It’s called Defender of the Wall and is the first part in the ‘Dragon of the North’ trilogy.

If you’ve read any of my other books, you will probably know that I am fascinated with Britain in the 5th century; a period which saw the island change from a rebellious Roman province into a patchwork of petty kingdoms under constant threat by Saxons, Scots and Picts. It was during these tumultuous times that the nations of England, Wales and Scotland began to emerge and the legend of King Arthur was born. My Hengest and Horsa trilogy dealt with the arrival of the Saxons and the start of what would become England and my Arthur of the Cymry trilogy concerned the response of the native Britons’ (i.e. the Welsh) to this. But there is so much of the story still left untold and one historical figure kept demanding to have his tale told.

Cunedag (or ‘Cunedda’ to use the more modern version) is the legendary founder of the kingdom of Gwynedd in North Wales. He was a big player in post-Roman Britain and has been mentioned in my books as the grandfather of Arthur (an invention of mine, but I had to fit Arthur into a royal family somewhere). This new trilogy will focus on Cunedag as he grows from a barbarian hostage to a Roman soldier and ultimately a British king.

So, who was Cunedag?

The 9th century Historia Brittonum claims that the ancestor of the infamous King Maelgwn of Gwynedd was one Cunedag who hailed from the region of Manaw Gododdin (the south side of the Firth of Forth in Scotland) and that he and his many sons came to Gwynedd to expel the Gaels (Irish invaders) over a hundred years previously. Manaw Gododdin was later made famous in the poem Y Gododdin by the bard Aneirin and the name likely comes from the Votadini tribe who dwelt just beyond Hadrian’s Wall.

The Welsh genealogies in the Harleian collection at the British Museum indicate that Cunedag was the son of Aetern and the grandson of Patern who has been identified with the Padarn ‘Beisrudd’ (scarlet robe) of Welsh legend (according to The Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain, the Coat of Padarn Beisrudd will fit a well-born man but not a churl). One interpretation of this is that Padarn was a Romano-British official called Paternus, who wore the red cloak of the Roman military, and was perhaps in command of Votadini troops loyal to Rome.

The idea of a barbarian tribe living just beyond Hadrian’s Wall serving as a buffer zone against the Picts is an intriguing one and perhaps explains why Padern’s grandson, Cunedag, would later move south to drive more of Rome’s enemies from Britain’s shores. But who sent him? If Cunedag was King Maelgwn’s grandfather, then he would have lived right at the end of Roman rule and the beginning of post-Roman Britain. This was a chaotic period of rebellions and usurpers and Cunedag could have been following the orders of anybody from Stilicho, the great Roman general sent to clear things up in the 390s to Vertigernus, the villainous ‘Vortigern’ of later legend.

Hadrian’s Wall was the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, but there seems to have been friendly ‘buffer’ tribes like the Votadini between it and the more hostile Pictish tribes to the north.

Hadrian’s Wall was the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, but there seems to have been friendly ‘buffer’ tribes like the Votadini between it and the more hostile Pictish tribes to the north. Whatever the details were, it seems clear that Cunedag, a Votadini chieftain who lived beyond the borders of Roman Britain, journeyed to the region of north Wales called Venedotia (Gwynedd) with a number of sons and established a dynasty that would survive for four-hundred years. The genealogies claim that he married a woman called Gwawl who was a daughter of the legendary Coel Hen, the progenitor of many royal families in the ‘Old North’. As for Cunedag’s sons, nine are mentioned in the genealogies, given the names Rhufon, Dunod, Ceredig, Einion, Dogfael, Edern, Tybion, Ysfael and Afloeg. Certain areas of North Wales seem to have been named after his sons (Ceredigion after Ceredig, Rhufoniog after Rhufon etc.), or we may be dealing with a semi-mythical list of rulers concocted to explain the names of kingdoms.

We know very little else about Cunedag, though a poem titled ‘The Death Song of Cunedda’ appears in the Book of Taliesin and is the usual rousing stuff about smiting enemies and shivering spears without giving us much detail about his life. The Historia Brittonum claims his firstborn, Tybion died in their homeland of Manaw Gododdin and the genealogies suggest that Cunedag was succeeded by his other son, Einion named ‘Yrth’ (‘the Impetuous’) who ruled Gwynedd until around 480. Cunedag’s dynasty lasted until the 9th century and he was the ancestor of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, the first and only king to unite all of Wales in 1055.

The red dragon of Wales may also trace its lineage to Cunedag. Various Welsh rulers have been referred to as ‘dragons’, the earliest of which is Cunedag’s grandson, Maelgwn and the Welsh word ‘draig’ is often used to mean ‘warrior’. But the motif seems to go back even further. A legend in the Historia Brittonum tells us of Vortigern’s attempts to build a tower which are frustrated by the fighting of two dragons inside the hill below it. The white dragon, we are told, represents the Saxons and the red, the native Britons. The symbolism may even go as far back as the draco military standard of Roman cavalry units which would have been a common sight in Cunedag’s time and possibly even a standard he served Rome under.

The draco standard was carried by late-Roman cavalry units and is a possible ancestor of the Welsh dragon. This replica draco was made by Stefan Jaroschinski. For more info, visit Robert Vermaat’s site here.

The draco standard was carried by late-Roman cavalry units and is a possible ancestor of the Welsh dragon. This replica draco was made by Stefan Jaroschinski. For more info, visit Robert Vermaat’s site here.

December 9, 2024

An Anglo-Saxon Yule

‘Tis the season for many things. Carols, late night shopping, mulled wine and wildly inaccurate social media posts about pagan Christmas traditions.

Every year, the internet is inundated with posts about how Christmas is actually a pagan holiday and that everything from Christmas trees to Santa Claus have their origins in pre-Christian traditions. While it is true that Yule was the name of an Anglo-Saxon midwinter festival, its connection to Christmas and much of the traditions surrounding it are often misunderstood. So, how did the Anglo-Saxons celebrate Christmas and was there a pagan precursor to it? If so, what was it like?

Let’s start with the Anglo-Saxon calendar as found in Bede’s 8th century The Reckoning of Time. Bede refers to the months of December and January as ǣrra ġēola (‘before geola’) and æftera ġēola (‘after geola’). Now, ‘geola’ is a word which has come to us in the modern form ‘yule’ and is etymologically connected to the Old Norse ‘jól’ and the modern Scandinavian ‘jul’. But what exactly was geola?

The short answer is; we don’t know. In Old Norse sources, jól seems to mean a feast of some kind. The phrase ‘Hugin’s Jól’ is used to refer to a battlefield, Hugin being one of Odin’s ravens and ‘Jól’ in this context being tasty feast of corpses. Festive stuff. Also, one of Odin’s nicknames is ‘Jólnir’ (‘the yule one’), perhaps signifying that he is a bringer of feasts.

Bede also references ‘Mōdraniht‘ (literally ‘Mother’s Night’) as being a pagan celebration held on December 25th. What this ‘mother’s night’ entailed or what its connection to yule was is left exasperatingly vague with Bede only commenting that certain ‘ceremonies’ were held that night. We have no idea what those ceremonies were but, it’s likely it had something to do with the winter solstice.

The solstice was a big event throughout Europe and it was common to slaughter livestock to avoid having to feed them all winter. This would create a surplus of meat to be eaten and a big feast would be the natural result of this. Description of Jól in the Norse sagas show it was a time of feasting, sacrifice, drinking toasts to the gods and swearing oaths (curiously while touching a sacred boar which was then sacrificed). This is a possible precursor to the tradition of New Year’s resolutions. King Haakon I of Norway went to great lengths to conciliate his pagan and Christian subjects by merging Jól and Christmas by law, suggesting that the two festivals had previously been separate and had coexisted in the same society for a time.

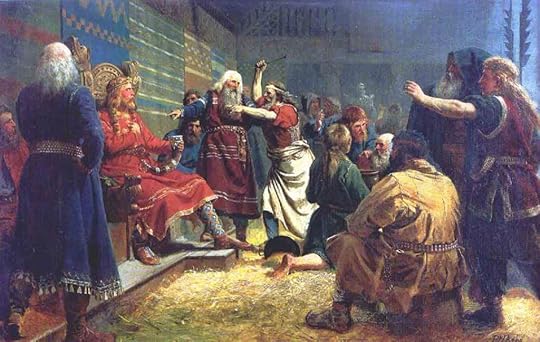

King Haakon I of Norway struggled to reconcile his pagan and Christian subjects and is depicted here being attacked at a jól feast for refusing to eat horse meat. (Håkon den gode, 1860, by Peter Nicolai Arbo).

King Haakon I of Norway struggled to reconcile his pagan and Christian subjects and is depicted here being attacked at a jól feast for refusing to eat horse meat. (Håkon den gode, 1860, by Peter Nicolai Arbo).Whatever Yule represented, it was a time of year which saw an increase in supernatural phenomena. Creepy encounters with the undead often occurred in the depths of winter in Icelandic sagas and this is perhaps the root of the longstanding tradition of ghost stories being told at Christmas, best exemplified by Charles Dickens and M. R. James. The Wild Hunt also seems to have a connection with this time of year, being a procession of ghostly huntsmen, birds and beasts that streak across the sky in the folklore of many Germanic-speaking countries. The leader of this hunt varies and is sometimes Odin/Woden/Wotan, which perhaps explains the god’s nickname of ‘Jólnir’.

Many theories try to link the Wild Hunt with the figure of Father Christmas/Santa Claus and, while the image of a bearded fellow leading a cavalcade of horned beasts across the sky is comparable, the link is tenuous at best. And while we’re mythbusting, the tradition of the Christmas tree isn’t attested to until the 16th century although it is certainly possible that pagans decorated their homes with evergreens (the only type of flora available in midwinter).

“Wodans wilde Jagd” by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882)

“Wodans wilde Jagd” by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882)It is interesting to note that the birth of Jesus wasn’t much of a big deal until the early Middle Ages, with Easter being the far more important date. This was mainly because nowhere in scripture does it say exactly when Jesus was born. There is evidence that various dates were celebrated as early as the 2nd century but it wasn’t until the Chronograph of 354 A.D. that December the 25th was established as Jesus birthday, a date which coincided with the winter solstice (according to the Julian calendar). The assimilation of pagan festivals like Yule, Saturnalia (a Roman festival in honour of the god Saturn) and Sol Invictus (a sun god of the late-Roman Empire) as a way of easing conversion may well have been the reason for selecting this date. In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days from the nativity to the epiphany as a sacred and festive season and emphasised the duty of fasting in preparation for the feast.

The Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons does not seem to have caused Yule to vanish and there is no evidence of Christians trying to ban it. This suggests that it was not an overtly pagan festival, but rather a somewhat secular celebration of the year’s end and the solstice, compatible with Christianity. After all, everybody enjoys a good feast and it seems that the meaning of Yule simply changed as more and more people became Christian without the trappings of the festival themselves changing all that much. This is certainly in line with the 6th century mission of St. Augustine who, in his conversion of the English, was commanded by Pope Gregory to destroy pagan idols but not the temples which should instead be appropriated for Christian use.

While the word ‘Christmas’ (from the Anglo-Saxon word, Cristesmæsse), doesn’t appear until 1038, it seems that the Christianised Anglo-Saxons were celebrating the nativity since at least the 8th century. The cleric Ecgbert of York stated that “The English people have been accustomed, in the full week before the Nativity of the Lord, and also up to the 12th day, to fast, observe vigils and prayers, and to give alms both to monasteries and to the poor.”

Christmas retained Yule’s tradition of oath swearing and became a favoured date for baptisms, important declarations and coronations. The crowning of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Carolingian Empire in the year 800 saw an increase in the popularity of the festival and when William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, he too was crowned on Christmas Day. This date heralded the end of Anglo-Saxon England but, as we have seen, many of its yuletide traditions have continued to this day.

Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne. Christmas Day became a popular time for coronations in the Middle Ages.

Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne. Christmas Day became a popular time for coronations in the Middle Ages.Don’t forget, if you are interested in the mythology behind Christmas and Yule traditions, then you can pick up my own book of short stories that explore the festive season through the ages. All profits go the Save the Children.

December 5, 2024

Stocking Up on Historical Fiction!

Seasonal greetings! With December now upon us, I’m sure I’m not alone in wanting to stay indoors with a good book, preferably in front of the fire, with snowflakes drifting past the window. Now’s the perfect time to stock up your Kindle with some great historical fiction bargains! My own book – Sign of the White Foal – is part of the ‘Stocking Up on Historical Fiction’ group promo, along with a ton of other great titles. So, check it out and pick up some bargains!

November 14, 2024

Research Nuggets: Who were the Picts?

As work continues on my new trilogy, I thought I’d write a little about a group of people who play a major role in the story. Few peoples are as misunderstood as the Picts, not helped by consistently outlandish depictions in movies and TV. Did they really paint themselves blue? Were they Scottish? By delving into the history behind them, the Picts are revealed to be a mysterious, although very real people who played a big part in British history.

Pictish raid on Hadrian’s Wall, AD 360 (Illustration by Wayne Reynolds for Pictish Warrior AD 297 – 841 by Osprey Publishing)

Pictish raid on Hadrian’s Wall, AD 360 (Illustration by Wayne Reynolds for Pictish Warrior AD 297 – 841 by Osprey Publishing)From their first mention in Roman sources at the end of the 3rd century A.D. to their eventual assimilation by the Kingdom of Alba in the 10th century, the Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now Scotland, though our knowledge of their culture is notoriously lacking.

As the Latin word ‘Picti’ means ‘painted’ it is believed that the Picts were so called due to their practice of either tattooing or painting their bodies. This was a practice used by many Celtic cultures and in fact, centuries earlier, Julius Caesar himself noted that “All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue colour, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible.” Even the name ‘Britain’ stems from the Greek word ‘Prettanikē’ which is possibly a translation of a Celtic word meaning ‘painted ones’. It is therefore possible that the Picts were culturally no different from other inhabitants of Britain but, due to never having been conquered by the Romans, they continued to paint/tattoo themselves into the 3rd century, thus earning a distinction from those Britons who no longer did so due to becoming Romanised.

The northern frontier of Rome’s province of Britannia was a hard one to keep and the Emperor Hadrian built a wall across the island to protect the southern part. The frontier was extended by Hadrian’s successor, Antonius, who built a second wall a 100 miles north but this ‘Antonine Wall’ was abandoned less than 20 years later. The inhabitants of Britain north of these walls were often referred to as ‘Caledonians’ rather than Picts until at least the 3rd century, but the Caledonians may have only been the name of one of the nearest tribes which the Romans were in contact with.

Caledonian tribesman, AD 200 (Illustration by Wayne Reynolds for Pictish Warrior AD 297 – 841 by Osprey Publishing)

Caledonian tribesman, AD 200 (Illustration by Wayne Reynolds for Pictish Warrior AD 297 – 841 by Osprey Publishing)Towards the end of Roman rule in Britain, the west coast of the island came under increasing attack by Gaelic-speaking raiders from Ireland whom the Romans referred to as ‘Scotti’. The Picts found their territories shrinking as these ‘Scots’ began to settle and form their own kingdoms such as that of Dál Riata in Argyll (literally ‘coast of the Gaels’). That didn’t stop the Picts from joining forces with the Scots in the Barbarian Conspiracy of 367 A.D. in which they, along with the Attacotti and Saxons overran Britannia’s defenses on all sides in what may have been a coordinated attack.

Although defeated, the Barbarian Conspiracy was the beginning of the end of Roman rule in Britain and, in 407, the usurper Constantine left Britain with the last of its legions, never to return. While there are several records of Pictish attacks below Hadrian’s Wall which took advantage of the chaos following the Roman withdrawal, the Picts had their work cut out for them in holding onto their own territories in the face of Scottish expansion. While the Picts had never really been a united people, a sense of Pictish identity grew with the dominance of the Kingdom of Fortriu (named after the Verturiones tribe) from the 7th century onwards.

By the Middle Ages, ‘Pictland’ had become ‘Scotland’ but exactly how is uncertain. As well as suffering Viking raids, the Picts of Fortriu frequently warred with the neighboring kingdom of Dál Riata and eventually merged with it and the Gaelic language became the dominant tongue in the north. By the 10th century, the area was referred to as the Kingdom of Alba (Alba being the Gaelic word for Britain) and after it absorbed Strathclyde and Lothian in the 12th century, it became known as the Kingdom of Scotland by English speakers.

The Picts left no written records, so we aren’t even sure what language they spoke although it was likely a Brythonic language akin to Welsh. They did leave many standing stones carved with distinctive symbols which, along with their unusual practice of tattooing/painting themselves blue, has made them a mysterious ‘lost’ people ripe for works of fiction.

The Pictish fort of Dundurn, AD 683 (Illustration by Peter Dennis for Strongholds of the Picts by Osprey Publishing)

The Pictish fort of Dundurn, AD 683 (Illustration by Peter Dennis for Strongholds of the Picts by Osprey Publishing)