Chris Thorndycroft's Blog, page 4

August 8, 2023

‘Bucceneer: The Early Life and Crimes of Philip Rake’ Now Available!

My newest historical fiction novel – Buccanner: The Early Life and crimes of Philip Rake – is finally on sale from Amazon! It is available in print and for Kindle as well as being in Kindle Unlimited. You can get your copy here!

March 18, 2023

Research Nuggets: Robert Drury’s Journal

In 1729, a book was published claiming to be the journal of one Robert Drury, a castaway who had lived with the people of Madagascar for fifteen years. Madagascar; or Robert Drury’s Journal, during fifteen years captivity on that Island is an intriguing and hair-raising tale of shipwreck, slavery, piracy and adventure that could easily sit alongside the fanciful novels of the period such as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. In fact, Defoe’s name would often be connected with the novel in the following centuries as people began to debate the authenticity of the journal.

Robert Drury, according to his journal, was a 17-year-old boy from Tower Hamlets, London who set out aboard the Degrave for India in 1701. The ship sprung a leak on its return voyage and the crew were forced to abandon it on the coast of Madagascar where they were taken captive by the local king Andriankirindra. A botched escape attempt saw most of the sailors killed but Robert survived and was given to another king whom he served as a slave for ten years, tending to bees and cattle.

When war broke out, Robert took the opportunity to escape and headed north, winding up at the port of St. Augustine (now called Toliara) which was something of a haven for European pirates. By making friends with people who had connections in England, Robert was able to get word to his father that he was alive and his father arranged passage home for him aboard an English slaving ship.

The journal is an astonishing account that seemed almost too fanciful to be true and, by the 19th century, it was widely regarded as a piece of fiction ghost-written by Daniel Defoe. As well as being stylistically similar to Defoe’s work and sharing the same publisher, there were several previous sources that Defoe might have used in describing the peoples and customs of Madagascar including the 1658 History of Madagascar by Etienne de Flacourt.

But Robert Drury did exist and research in recent years suggests a degree of authenticity to his journal. Archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson was studying burial customs in Madagascar in the mid-1990s and found many things in Drury’s journal to be true such as place names, customs and lexicographic terms which did not appear in earlier sources. While it now seems that there is at least some truth to Drury’s account, it is still entirely plausible that Daniel Defoe helped the self-confessed uneducated man pen his journal, embellishing some elements while also providing background information to Madagascar cribbed from Flacourt’s history. This aside, Robert Drury’s journal remains a thrilling account and an important early source on Madagascar and its peoples which were almost entirely alien to European audiences at the time.

Madagascar plays an important part in my upcoming novel of piracy in the 18th century and Robert Drury’s account of a European’s impressions of Madagascar and its peoples was a great resource in the writing of it. Watch this space for more details about my upcoming novel!

February 5, 2023

Research Nuggets: The Queen’s Jewels

The research part of writing historical fiction is one of the most rewarding parts about it and I thought I’d share with you some of the little gems that turn up.

The sinking of the 1715 Spanish treasure fleet is a major part of my current series of novels focusing on piracy in the Caribbean. Setting out from Havana, the Spanish treasure fleet carried wealth from Spain’s colonies in the New World including thousands of chests of coins, gold and silver bars, gold dust, jewels and pearls which had been stockpiled for three years, delayed by the War of Spanish Succession.

The war over, it was deemed safe to make the voyage to Spain but there were further delays meaning that the fleet did not set out until late July, during the Caribbean’s hurricane season. One of these delays provides an amusing and oft-reported anecdote. King Felipe of Spain had recently married Isabel Farnesio of Parma and his new wife apparently refused to consummate their marriage unless she received jewels of her choosing from the New World.

One can only imagine the haste demanded by the Spanish king and eight chests of jewels including a heart studded with pearls, an emerald ring and a rosary made of pure coral were loaded aboard the ships before they set out. Unfortunately for both king and queen, the fleet never made it to Spain as it was wrecked by a hurricane on the Florida coast.

It’s a great story but may owe more to myth (and the 1977 adventure movie The Deep) than history. As this article by Alex Kuze correctly points out, Felipe and Isabel’s son was born in January of 1716, meaning that the queen was already pregnant before the fleet even set out! Perhaps the queen reneged on her conditions, or perhaps this is just another tall tale connected with the already legendary sinking of the 1715 Spanish treasure fleet.

December 26, 2021

Christmas Fruitcake

“It’s fruitcake weather!” states the old lady in Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory. Originally published in Mademoiselle magazine in December 1956, this semi-autobiographical tale of a boy and his older, unnamed cousin as they gather ingredients for thirty fruitcakes in preparation for Christmas is a touching nostalgic piece that has become an American Christmas tradition as much as fruitcake itself. The cake in question is often heavy and dark containing nuts, spices and dried fruit soaked in alcohol (in the case of the prohibition-era set A Christmas Memory, bathtub whiskey purchased from a bootlegger called ‘Haha’ Jones). Similar to the British Christmas cake (which is typically decorated with layers of marzipan and royal icing), the American fruitcake is usually plainer and decorated with nuts and dried fruit and maybe an apricot glaze.

My own American-set Christmas short story – A Brooklyn Fairy Tale – takes place on Christmas Eve where the stories of several characters overlap and the shadows of the past loom large over all. A young boy in dire straits comes face to face with a mythological figure in a red coat who is the sum of many different customs from New York’s colourful history.

Santa Claus, now a worldwide tradition, was once a peculiarly American phenomenon with his roots in New York. In my previous post, I showed how Saint Nicholas, a 4th century bishop in Asia minor, became a medieval patron of anonymous charity and a bringer of gifts to children. His cult was widespread from Greece to the Netherlands where he was known as ‘Sinterklaas’ and he emigrated along with the Dutch to the east coast of America in the 17th century where his name phonetically mutated to ‘Santa Claus’. There is a record in Rivington’s Gazette (New York City) of the celebration of the anniversary of St. Nicholas “otherwise called Santa Claus” in 1773 and in 1809, Washington Irving’s satirical A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker included a description of St. Nicholas as “riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.” In fact, it was Irving who helped shape the idea of a modern American Christmas, much in the same way Charles Dickens would do for the English a couple of decades later. Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1819 – 1820) not only included his Halloween-inspiring classic The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, but also four essays on Christmas traditions that revived public interest in the holiday.

In the 1820s, two anonymous poems forged the canon of Santa Claus further. Old Santeclaus with Much Delight (published in a small paperback book entitled The Children’s Friend: A New-Year’s Present, to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve by William B. Gilley in 1821) is the first to describe ‘Santeclaus’ as dressed in red (and not the red of a bishop’s robes). The poem is also the first reference of Santa using reindeer and arriving on Christmas Eve (instead of Saint Nicholas’s day of December 6th). In 1823, A Visit from St. Nicholas (more commonly referred to by its opening line ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas‘) was published anonymously in the Troy, New York Sentinel. Latter attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, the poem described Santa as “chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf” (despite also suggesting that he was small, riding a ‘miniature’ sleigh). The poem also gave Santa his eight reindeer and named them Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem.

American Protestants seemed ready to accept the idea of a separate Christmas gift-giver to Saint Nicholas (the veneration of saints considered a Catholic practice). In fact, it is curious that the tradition of St. Nicholas remained so popular among the Dutch; a predominantly Protestant people. Back in the 16th century, Martin Luther had already supported the idea of the Christ Child (or ‘Kristkindl’) bringing gifts to children on Christmas Eve rather than St. Nicholas on his feast day of December 6th and the name ‘Kris Kringle’ as an alternative name for Santa can be traced back to this. Thus, Santa became a different figure to his namesake St. Nicholas, and the day of his appearance became fixed on Christmas Eve.

Illustration to verse 3 of Old Santeclaus with Much Delight

Illustration to verse 3 of Old Santeclaus with Much Delight

An illustration from a 1862 edition of A Visit From Saint Nicholas

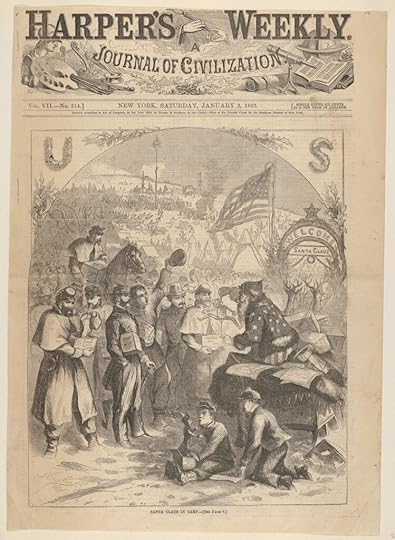

An illustration from a 1862 edition of A Visit From Saint NicholasThere were more additions to the Santa Claus mythos in the following decades. During the American Civil War, cartoonist Thomas Nast created the iconic image of Santa and later suggested that he came from the North Pole while, in 1889, the poet Katharine Lee Bates gave Santa a wife in her poem “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride”. It is perhaps the illustrations of Haddon Sundblom for the Coca-Cola Company in the 1930s that are most recognisable images of Santa today. Cynical voices will bemoan capitalist appropriation of folklore, but for many, the image of the jolly man in red and white holding a bottle of Coke is just another step in the continuing evolution of a cultural icon who, himself a patchwork of influences, has served many different purposes throughout the years; from a Protestant alternative to a Catholic saint, to a Civil War poster boy to a corporate marketing tool and beyond, he will undoubtedly continue to evolve.

Thomas Nast’s illustration for the 3 January 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly in which Santa visits Unionist troops dressed in an American flag.

Thomas Nast’s illustration for the 3 January 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly in which Santa visits Unionist troops dressed in an American flag.

‘Give and take, say I’ was Haddon Sundblom’s 1937 advertisement for Coca-Cola

‘Give and take, say I’ was Haddon Sundblom’s 1937 advertisement for Coca-Cola

A Brooklyn Fairy Tale is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

A Brooklyn Fairy Tale is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

December 24, 2021

17th Century Mince Pie

The sixth recipe I’m trying in connection with my seasonal anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice is for a traditional mince pie, 17th century style. That means it contains actual meat and is more of a savory dish.

Mince pies are still popular Christmas treats in England but today they are small, sweet pies containing dried fruit and spices. Originally they included actual shredded (or ‘minced’) meat. They date back to the Middle Ages when crusaders returned from the holy land with new spices as well as cooking customs that blended meat with fruit (similar to the ‘tagine’ dishes of north Africa). I’ve tried different recipes for mince pies from different eras (such as this medieval one) but, as my short story Evergreen takes place in 17th century England, I wanted to try one from that era. The recipe I used is from a cookbook by Elizabeth Jacob (1654-c. 1685), an excellent reproduction of which can be found here.

Evergreen is set in Civil War England and sees a trio of siblings time travel back to the Anglo Saxon era where they become embroiled in a different conflict, this time between Christianity and Paganism.

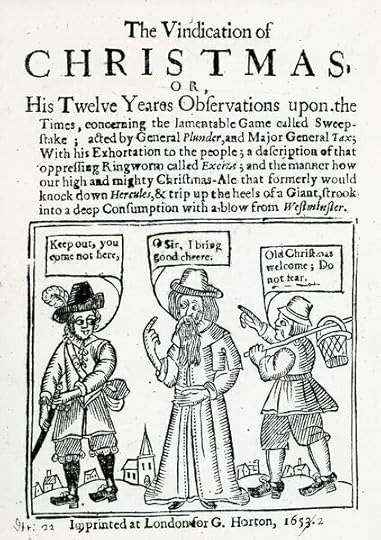

The English Civil War saw a parliamentarian victory over King Charles I who was beheaded, and the monarchy replaced by the Commonwealth of England with Oliver Cromwell as its Lord Protector. Cromwell, like most of his followers, was a staunch puritan. Anything remotely Catholic was prohibited. Laws were passed to regulate people’s moral behaviour, theaters were closed down and observance of Sunday was strictly enforced. The celebration of Christmas was deeply frowned upon and seen as a ‘popish’ observance marked by gambling, drunkenness and gluttony. Measures were taken to abolish it and the reaction from Royalists (and anybody else who liked a bit of fun) was fierce. The figure of ‘Father Christmas’ began to emerge as a personification of the season as it had been in the ‘good old days’. There had been secular personifications of Christmas in the Middle Ages with names like ‘Sir Christmas’ or the ‘King of Christmas’, but the first visual representation of the figure was in a 1652 Royalist pamphlet called The Vindication of Christmas which showed a bearded, robed figure lamenting the lack of Christmas spirit in ‘this headless country’ (pun most likely intended).

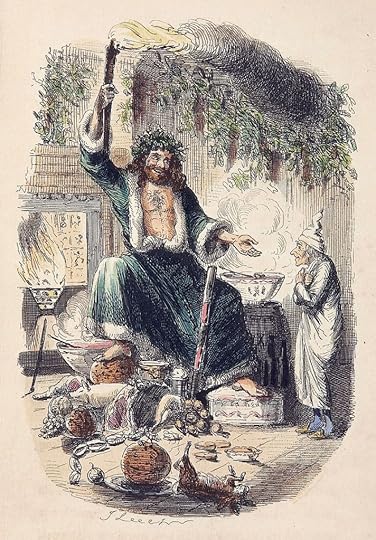

After the restoration of the monarchy and the return of King Charles’s exiled son in 1660, there was little need for Father Christmas as a political figure and he, along with Christmas celebrations in general declined in the 18th century. It was the Victorians (and Charles Dickens in particular) who encouraged a revival in festive customs and Father Christmas returned with vigour. At this stage he was often depicted as a long-bearded, fur robe-wearing figure crowned with holly (sometimes riding a goat), who was the embodiment of merrymaking and good cheer (and not necessarily a giver of gifts to children). John Leech’s illustration of the ‘Ghost of Christmas Present’ in Charles Dickens’s 1843 novel A Christmas Carol is a fair approximation of the character.

John Leech’s illustration of the ‘Ghost of Christmas Present’ in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

John Leech’s illustration of the ‘Ghost of Christmas Present’ in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. By the 20th century, Father Christmas merged with the American ‘Santa Claus’ and became the red-coated, white-bearded bringer of gifts for children. The origins of Santa are quite different to those of Father Christmas and the two were far from synonymous once upon a time. For the story of how a 4th century bishop from Asia Minor became an American cultural icon, check back here in a few days for the final post in this series!

December 21, 2021

Savillum

The fifth recipe I’m trying in connection with my seasonal anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice is another ancient Roman one, this time for a honey-drenched cheesecake called ‘Savillum’.

I already did a recipe for the Roman winter festival of Saturnalia but my story ‘The Wonderworker’ also takes place in the Roman Empire (albeit in the Greek-speaking province of Lycia). By the 4th century, the people of Lycia would have been a mixture of Christians and pagans (of both Roman and Greek faiths). Some would have celebrated Saturnalia, some the birth of Sol Invictus and some the nativity of Christ. We don’t know exactly what they would have eaten at these festivals but one dish mentioned in Cato’s De Agri Cultura is Savillum; a mixture of cheese (such as ricotta) with honey, flour and egg baked into a moist flan afterwards drizzled with honey and poppy seeds. You can find a good recreation of the recipe at Pass the Flamingo.

My short story The Wonderworker tells the story of the Christian slave Nikolaus who, after being freed from the quarries of Prokonnesos, returns to his home of Lycia to find it in the grip of famine. Using his newfound inheritance, Nicholas embarks on a crusade of charity and goes on to be remembered as the gift-giving ‘wonderworker’, Saint Nicholas.

Historical sources for the life of Saint Nicholas are patchy but they tend to agree that Nicholas was born in the town of Patara in Lycia (a Roman province on what is now the southern coast of Turkey) in the 3rd century; a tumultuous time of great friction between Christianity and paganism. Christianity was growing rapidly despite persecutions which saw many Christians executed or imprisoned in places like the island of Prokonnesos. The 9th century text The Life of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker by Michael the Archimandrite tells us that Nicholas’s parents died in his youth and left him with a great inheritance. He became the bishop of the nearby town of Myra when he was just a boy and used his parents’ wealth for great acts of charity, most notably, the gifting of three destitute young women with purses of gold (which he threw through their window at night), thus saving them from being sold into prostitution by their father. Nicholas also embarked on a crusade against paganism and tore down many temples and idols including the great temple of Artemis. Despite this rather intolerant stance on other faiths, Nicholas is better remembered for several good deeds which include saving a group of sailors from shipwreck and easing the famine of his native Lycia by persuading the captains of grain ships to spare a little of their cargo (while ensuring that the overall weight of the cargo remained the same).

The dowry for the three virgins (Gentile da Fabriano, c. 1425, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome)

The dowry for the three virgins (Gentile da Fabriano, c. 1425, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome)The cult of Saint Nicholas was established at least by the 6th century and was widespread with people from Greece to the Netherlands venerating him as a patron of sailors, children and anonymous charity. His feast day is celebrated on the 6th of December (the date of his death, according to the Julian calendar) and, by the middle ages, was marked by giving gifts to children in his honour. It was the Dutch immigrants of New Amsterdam (New York) who brought the tradition of Saint Nicholas (or ‘Sinterklaas’, as they called him) to America where it merged with figures from other cultures (like the English ‘Father Christmas’). By the 1800s, the figure of Santa Claus had been born, his name a phonetic deviation of ‘Sinterklaas’.

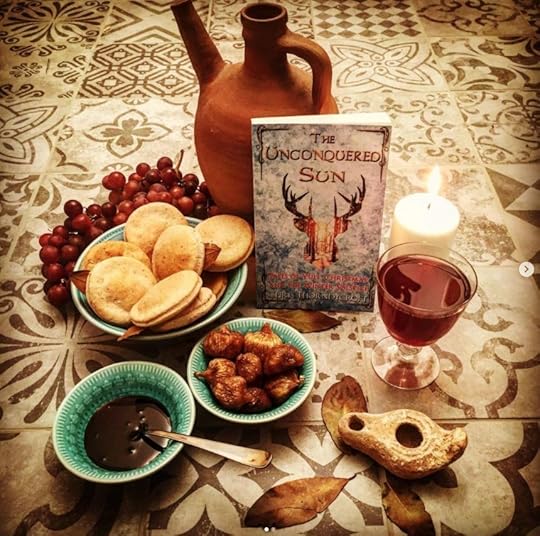

The Wonderworker is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

The Wonderworker is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

December 13, 2021

Roscón de Reyes

The fourth recipe I’m trying in connection with my seasonal anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice is the traditional Spanish three kings cake, roscón de reyes.

This circular sweet bread is similar to brioche and is often decorated with candied fruits, nuts and dates. sometimes the cake sandwiches a layer of whipped cream. Eaten on the Epiphany (January 6th), in commemoration of the visit of the three magi (or ‘kings’) to the baby Christ, the roscón de reyes often contains a plastic or ceramic figurine of the baby Jesus, the finder of which is promised good luck for the entire year.

In my story The Last Magi (set in Spain, 1666), young Esteban, an apprentice to an alchemist in Barcelona, learns that his master is hundreds of years old and was in fact, one of the magi who followed a star to Bethlehem to worship the baby Jesus.

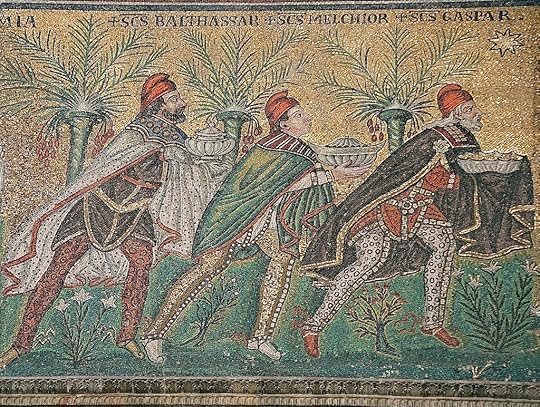

An early 6th century image of the three magi from a Byzantine mosaic at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy (Nina-no, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons)

An early 6th century image of the three magi from a Byzantine mosaic at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy (Nina-no, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons)Only ever mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew, the magi were said to have come ‘from the east’ to worship the newborn king. Despite many a nativity scene depicting the images of three kings bearing gifts, the biblical magi were not numbered and, rather than being present at the nativity, seem to have visited some time later (but it is unknown if it was that same winter). Nor were they mentioned as being kings. ‘Magi’ (from which we get our word ‘magic’) is of Persian origin and could mean a number of things from astrologers to Zoroastrian priests. The idea that the magi were kings probably comes from identification with Old Testament prophecies that claim the messiah will be worshiped by kings and the number three from the explicit mentioning of three gifts in the Gospel of Matthew; gold, frankincense and myrrh. Certainly by the 6th century, the magi were regarded as kings and were often depicted as being three in number named Gaspar, Melchior and Balthazar. The tradition of three kings bringing gifts to children on the eve of the Epiphany has become a tradition in Spain and Spanish speaking countries with the first parade of the three kings recorded in the mid-19th century.

The Last Magi is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

The Last Magi is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

December 9, 2021

Mustacei (Must Cakes)

The third recipe I’m trying out this December in connection with my seasonal anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice is for an ancient Roman delicacy called ‘must cakes’.

‘Must’ is the crushed fruit used in wine making before the yeast is added to begin fermentation. A recipe from Cato the Elder calls for must to be added to flour, cheese, aniseed and cumin. This is formed into little cakes, each baked with a bay leaf under them. These aromatic cakes are savory but taste great with date syrup and a glass of mulsum (wine infused with honey, nutmeg and cloves which the Romans drank as an aperitif).

Set in the ancient world, my story In the House of Capricorn tells of a young shepherd boy in 1st century Judea called Samuel who comes to learn that he has lived many previous lives, always pursued by a dark force that threatens to snuff out his light. As strange events occur near the town of Bethlehem, Samuel realises that after this night, the world will never be the same again …

The Roman god Saturn with his scythe signifying his role as an agricultural deity. Fresco from the House of the Dioscuri at Pompeii, Naples Archaeological Museum.

The Roman god Saturn with his scythe signifying his role as an agricultural deity. Fresco from the House of the Dioscuri at Pompeii, Naples Archaeological Museum.Mustacei were eaten during the Roman festival of Saturnalia which began December 17th and could last until December 23rd. It was in honour of the god Saturn, an agricultural deity who had reigned over the world during its Golden Age which was marked by peace, harmony and bountiful harvests. In mimicry of this mythical age, there was a role reversal between slaves and masters with the former treated to a banquet and, in some instances, even served by their masters. Saturnalia began with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn on the 17th followed by a public banquet. Businesses, courts and schools would close and people would go home for several days of private merrymaking with the 19th a day of gift giving. It was a riotous holiday marked by eating, drinking, dancing and gambling. It was also described as a festival of light with widespread use of wax candles which were sometimes exchanged as gifts.

A dedication made to Sol Invictus (the ‘unconquered sun’) whose birth was celebrated on the 25th of December in the late Roman Empire

A dedication made to Sol Invictus (the ‘unconquered sun’) whose birth was celebrated on the 25th of December in the late Roman EmpireThe trading of gifts, feasting and the lighting of candles in the darkening days of December influenced modern Christmas traditions as Saturnalia continued to be celebrated as a secular holiday long after it was officially removed from the calendar. Its close proximity to the winter solstice meant that Saturnalia had merged with the later festival of the birth of Sol Invictus – the ‘Unconquered Sun’. Although long worshiped in ancient Rome, the importance of the sun as a deity increased with Syrian influence in the 4th century AD and the festival of Sol Invictus was marked in the Philocalian Calendar of 354 AD as taking place on the 25th of December (the day of the solstice, according to Julian reckoning). That same calendar also gives this date as the birth of Jesus. Early Christians didn’t celebrate Christ’s birth at all (primarily because the gospels don’t give a date), but the 4th century had seen a gradual focus on its importance with the first celebration of the nativity taking place in Alexandria on the 25th of December, 432 AD. It is possible that this date was chosen to coincide with the festival of Sol Invictus (and certainly the winter solstice) however, there is little evidence that the birth of Sol Invictus was celebrated on the 25th before the mid-4th century, so it may be the other way around. It’s possible that the festival of Sol Invictus was identified with this date by pagans as a response to the appropriation of the winter solstice by Christianity while another theory is that Jesus is in fact Sol Invictus, suggesting a Christian interpretation of a pagan cult that turned the worship of the sun to the worship of the ‘son’ born on the 25th of December.

In the House of Capricorn is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

In the House of Capricorn is one of seven short stories in the Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

December 5, 2021

Gingerbread Hearts

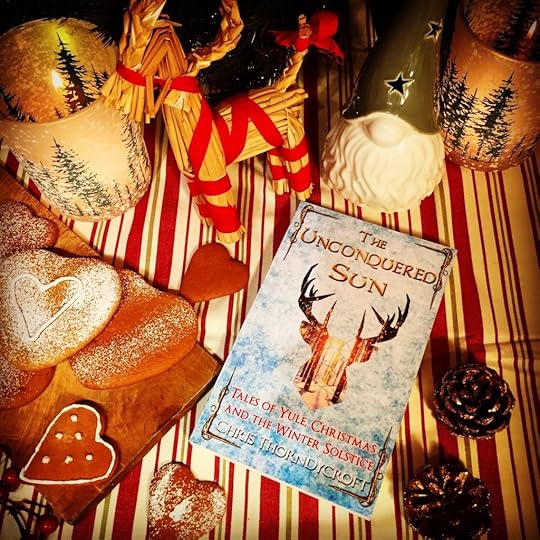

Continuing my challenge to make one recipe per story from my Christmas anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice I made gingerbread hearts this weekend.

Something of a Norwegian tradition, gingerbread hearts (or ‘pepperkakehjerter’) are often hung in windows or on trees for decoration along with other forms including little men and women, trees, reindeer and even elaborate houses decorated with icing and sweets. Literally meaning ‘pepper cake’, pepperkake usually doesn’t contain actual pepper these days and resembles the aromatic cookie form of gingerbread (gingerbread itself being a wide term for baked goods ranging from soft loaves of cake to flat biscuits).

Set in 19th-century Norway, The Quest for the Julbukk, is the adventure of a boy called Haakon, youngest of three brothers, who decides to trap a nisse; the household spirit that dwells on his farm. Enraged at this treatment, the nisse demands a service of Haakon, namely to accompany him on a dangerous quest to rescue the Julbukk – a mythical goat and bringer of gifts at Yule – which has been captured by the trolls who live under the mountains. If the Julbukk is not recaptured, the sun will not rise in the morning.

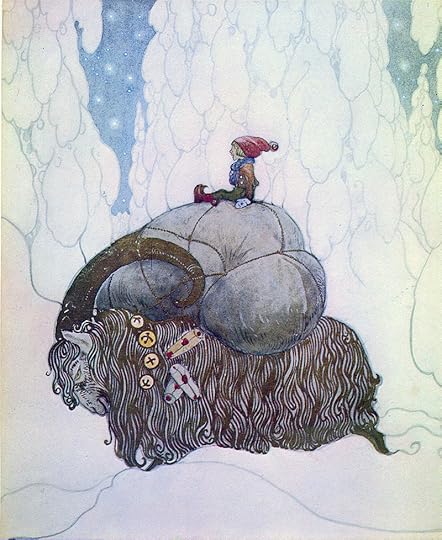

Julbocken (1912) by the Swedish artist John Bauer

Julbocken (1912) by the Swedish artist John Bauer The Julbukk (literally the ‘Yule Goat’) is an odd bit of Scandinavian mid-winter folklore. The tradition of making a julbukk from the harvest’s last sheaf of grain suggests a pagan element involving fertility. The idea of a horned yuletide figure possibly connects the Julbukk to the ‘Krampus’ figure of the alps and even Santa’s reindeer. The Julbukk was a gift-bringer and occasionally a male relative would dress up as a goat or a horned man and come to the door bearing presents. Other traditions involve ‘julbukking’; a form of trick or treating where people in masks go door to door singing carols (and occasionally performing pranks) in exchange for food and drink.

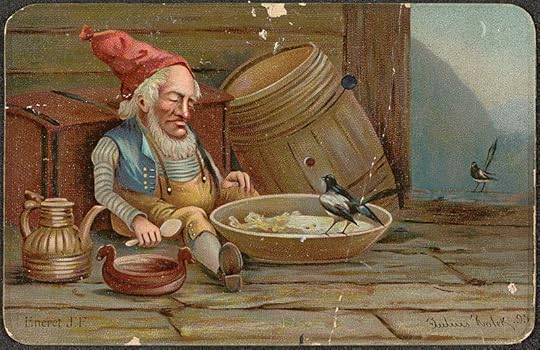

The mid 19th century marked a shift from the Julbukk as the Christmas gift-bringer to the ‘nisser’. These small, gnome-like beings depicted with white beards and red woolen hats are probably descended from the pre-Christian idea of household gods. Some theories suggest that a nisse was the spirit of the farm’s first resident. Temperamental creatures, nisser would either help out around the farm or cause mischief and could be kept pacified by leaving out a bowl of porridge overnight. By the late 19th century, nisser were often seen in the company of the Julbukk bearing presents but the latter has more or less faded out in recent times and exists merely as a Christmas ornament made of straw. The figure of the single ‘julenissen’ (the ‘Yule Nisse’) has emerged as an answer to the American Santa Claus whose workshop elves bear more than a passing resemblance to this older Scandinavian tradition.

A nisse with his bowl of ‘julegrøt’ (Yule porridge) illustrated by Julius Holck, 1895

A nisse with his bowl of ‘julegrøt’ (Yule porridge) illustrated by Julius Holck, 1895The Quest for the Julbukk is inspired by the folk tales of Norway which were collected and published in the 1840s by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe. These tales include trolls that can smell the blood of Christians, flying ships, and variations on the ‘Askeladd’ character; the youngest of three brothers who, despite being the smallest and weakest, succeeds where his brothers fail. The efforts of Asbjørnsen and Moe were part of a mid 19th century drive to cement a distinct Norwegian identity based on its rural culture and traditions. For 400 years, Norway had been the lesser part of a union with Denmark. After being on the losing side of the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark was forced to hand Norway over to Sweden but not before Norway made a quick bid for independence by writing its own constitution in 1814. Despite being forced into a union with Sweden, Norway was allowed to keep its constitution and this newfound sense of patriotism heralded a cultural boom in the 1800’s. In addition to Asbjønsen and Moe’s work, Adolph Tidemand and Hans Gude painted Norway’s dramatic landscapes, composers Ole Bull and Edvard Grieg introduced rural folk music to the Dane-ified cities and Henrik Ibsen penned some of his greatest satirical plays. In 1867, Grieg and Ibsen collaborated on the play Peer Gynt with incidental music written by Grieg including ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’ becoming one of the world’s most recognisable pieces of classical music, instantly conjuring images of cavernous underground halls peopled with trolls.

‘The Quest for the Julbukk’ is one of seven short stories in the anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.

November 30, 2021

Linzer Biscuits

I set myself a challenge this season. To promote my Christmas anthology (The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice) , I’m making one recipe per story from the particular country that story is set in. Today I made Linzer biscuits.

Named after the city of Linz in Austria, Linzer cookies/biscuits are a popular Christmas delicacy in Austria and the US. They are descended from the ‘Linzertorte’ which is a lattice-crust tart filled with preserves dating back to at least the 17th century. It is unknown when the more modern ‘sandwich cookie’ versions started to appear but they made their way to America with Austrian and German immigrants in the mid-19th century. Similar to the UK’s Jammie Dodger, the Linzer biscuit is two layers of buttery almond dough with a shape cut in the centre of the top layer to reveal the jam/preserve within.

In my story ‘Krampus Unchained’ (set in Austria, 1741), four squabbling children unwittingly release Saint Nicholas’s demonic servant and are forced to work together to fix things. Krampus is a rather frightening figure from Alpine folklore who acts as a servant to Saint Nicholas as he brings gifts to children on December 6th (Nikolaustag). Possibly incorporating pre-Christian elements, Krampus is depicted as a hairy, long-tongued demon weighed down by chains (representing the binding of the devil by the Church). He carries a basket on his back and bundle of birch twigs with the implication that bad children will be punished and/or carried off. He is just one of many helpers to Saint Nicholas depicted in European folklore. Some of the others who fulfill near identical functions include Belsnickel of southwestern Gemany and Zwarte Piet of the Netherlands.

A 1900s greeting card depicting Krampus

A 1900s greeting card depicting Krampus

‘Krampus Unchained’ is one of seven short stories in the anthology The Unconquered Sun: Tales of Yule, Christmas and the Winter Solstice which explores various Christmas traditions from around the world. It is available from Amazon and all profits go to Save the Children UK.