Teodor Reljic's Blog, page 12

October 11, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #2 | Orrin Grey

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Baron von Werewolf Presents: Frankenstein Against the Phantom Planet by Orrin Grey

Check it: Orrin Grey’s contribution to Eternal Frankenstein has its close-second-person narration talk about a kid watching a movie. Now, an outwardly rational but profoundly misinformed part of your brain may be passing these signals right about now: Gee, a story about someone just sitting there watching a movie sure sounds boring as heck!

I hear that, I do. But not without raising you The Prayer to Ninety Cats by Caitlin R. Kiernan. Haven’t read it yet? That’s fine. Help yourself. I’ll wait. Really.

Done?

Okay, now comparisons are odious, and a comparison to one of the (pretty much) undisputed champions of contemporary weird fiction may feel particularly odious indeed. But Orrin Grey is not to be thrown away — a direct translation from my native Serbian that also happens to rhyme, hooray! — especially given that his recent short-story-anthology-Kickstarter* was a runaway success, and that his prolific output has proven he’s a name to watch out for, if nothing else.

But when talking about an anthology that aims to build on the literary reputation of an undisputed — no doubts about it in this case — classic, it’s also good to point out stylistic commonalities. After all, Frankenstein is the hook here, and intertextual joy is one of the main reasons both readers and writers tune into these books in the first place.

And I have a feeling that Grey will be the last person to contradict that statement, given how this story is shamelessly seeped in enough nostalgia to make the folks behind Stranger Things blush with (neon) envy.

Still from Frankenstein Conquers The World (1965)

To those with even the slimmest knowledge of what’s being channelled here, the title announces both the premise and the vibe of the piece: it’s a ‘Tales of the Cryptkeeper’/Elvira kind of affair, where Baron von Werewolf curates a selection of creepy flicks for an impressionable and eager young audience.

(Being non-American, my own first-hand exposure to this kind of thing is slim indeed, and I was mostly made aware of it through the legacy of Ed Wood and David J. Skal’s excellent The Monster Show)

But apart from the Tim Burton/Stranger Things element of a nostalgic love-in for all the things that made these ‘vintage’ horror films special, Grey reminds us of another key aspect of Shelley’s original novel: that when it came into contact with the Hollywood machine, it spiraled into directions that Shelley could never have imagined.

So now we have Frankenstein battling an entire planet populated by malignant alien forces. Which is distinctly separate from Shelley’s pained meditation on absent fatherhood and scientific hubris. But it’s also, of course, awesome! And it’s a joy to go along with Grey’s wide-eyed narrator: expectations are tugged for both of us, and the affection the young one feels for Baron von Werewolf is oddly touching.

So much so that when a moment of genuine menace arrives, you feel it in your guts. This, despite all the metatextual trappings and the story-within-a-story nature of Grey’s tale. The gaps in the already-mysterious film being presented by the Baron here also add their own spooky spice in the background.

A love letter to vintage monster mash-ups done with affection and grace.

Read previous: Amber-Rose Reed

*Please donate to our Patreon and help us make Malta’s first serialized comic book, MIBDUL. Thanks!

October 10, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #1 | Amber-Rose Reed

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Torso, Heart, Head by Amber Rose-Reed

I was gonna make all cool and not in fact start at the very beginning, but perhaps it’s a testament to the editorial prowess of Ross E. Lockhart that the opener to Eternal Frankenstein lured my bolshie self into going conventional, at least just this once.

Mostly, this is down to the fact that Reed’s story — more of a tone poem than anything else — latches onto some of the core themes of Mary Shelley’s original text in a way that’s succinct, seductive and with an aftertaste of irony that lingers and urges you to dive back in for that re-read.

Which, incidentally, you should be able to do with relative comfort and ease. Slightly dizzying the story may be in terms of any ‘narrative’ structure that you may expect, but it’s certainly brief enough to invite second helpings.

The anatomical segmentation suggested in the title announces Reed’s clever idea early on. To wit: just like Frankenstein’s creature is a ‘cut-up’ creation made up of various disparate parts, so does this very text appear to the reader as a fragmented series of images and incomplete episodes.

Opening with a pugilistic micro-chapter (whose title is not in fact suggested by the story’s title-proper) we are then taken to the ‘Torso’ — an upsetting episode witnessed by a carpenter or ironmonger — before proceeding to the ‘Heart’ and the ‘Head’. Each of these are stories that hint at Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; that have the whiff of that seminal text but that don’t try to pin it down and suck any remaining juice out of it by force.

An infant death, a thwarted love story and a father’s imploring letter to a young man pursuing his studies abroad. It’s only the final one that gives away an explicit connection to Frankenstein, including as it does a reference to a seemingly determined anatomy student…

And as in the ‘galleys’ that separate pages in a comic book, the reader is invited to fill in the rest. This is an inspiring take on the pastiche. Or rather, it shows that Reed openly resists one of the biggest temptations imaginable when submitting to anthologies like this: to amp up the cosmetic thrills of classic literary works and forcibly reshape them into something you’ve always wanted them to be.

Thankfully, what Reed does is more open, more worthy and, well… more eternal.

Read previous: Introduction

October 7, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon | Introduction

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

But first, kindly indulge me in a bit of a personal reverie on what made me fall in love with Mary Shelley’s seminal novel in the first place…

*

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is one of my favourite novels of all time. I guess this isn’t particularly unique – what with the book being the source of one of the most perennial features of multimedia pop culture since the beginning of the 20th century – but that doesn’t of course take away from the intense love I have for the original novel.

It’s not a childhood favourite, either: I first decided to finally tick it off my virtual to-read pile for a very functional reason. I was in the final year of my Bachelor’s course in English Lit at the local Uni, and one of the elective courses I chose that year was ‘Literature and Technology’, taught by the inimitable Prof Ivan Callus, and which had Frankenstein as a required text for obvious reasons.

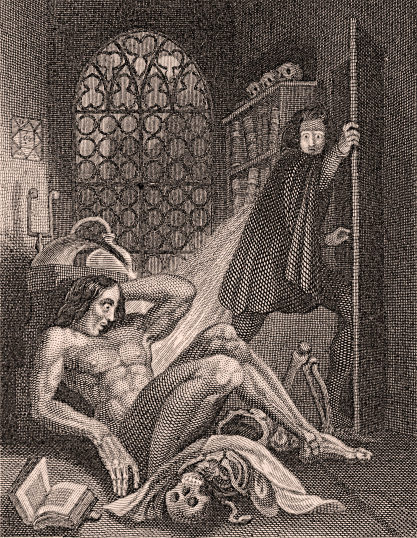

Frontispiece for the 1831 edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Illustrated by Theodore Von Holst (Steel engraving; 993 x 71mm)

My social life at Uni was at its highest ebb at the time, but so were degrees of academic stress – what with a dissertation to complete and synoptic exams to cram for – but despite all this, I decided to put everything aside and check out the austere Everyman edition of Shelley’s groundbreaking, genre-creating work from the University of Malta library and finish it asap.

I guess I expected it to be fun-by-accident, and stylistically creaky in a similar way to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, whose essence – in my humble opinion – was improved and made far cooler by subsequent iterations. In other words, I suppose I was expecting to find an old-timey version of all the things that have made Frankenstein great for generations to come.

But actually, I ended up being humbled by a novel whose raw power was undeniable. She wrote this when she was nineteen! I kept saying to myself in disbelief, but there was also something peculiarly appropriate to this fact. Far from being creaky, it moves at a breakneck (if pained) pace – the work of a young woman trying desperately to give shape to the confusing mess that life can sometimes be.

Portrait of Mary Shelley by Richard Rothwell (1840)

Despite the fact that – much like its central Creature – the novel mashes together various preoccupations (the scientist’s hubris, motherhood, absent fathers and the inability to function in the world as a context-less outcast), it also felt like a barely-edited transcription of a fever dream. Which is even more surprising given how the story is stacked together against various frame narratives – a gradual build-up with a shifting POV that immerses you deeper and deeper into, instead of alienating you from the story.

(It always saddens me to think just how outmoded this style of storytelling has become… how easily we would dismiss a novel that tries this nowadays as being ‘long-winded’ and/or accuse it of ‘taking ages to get going’.)

Thankfully, even if its pop culture counterparts sometimes loom larger – like Karloff’s original Hollywood creature – than the reputation of Shelley’s own novel (I wonder how many people familiar with the Frankenstein name even know there is a book), it’s heartening to know that Shelley is in fact getting respects from the quarters who matter. The legacy of this, her first novel, has been discussed and celebrated ad infinitum for various reasons, and I won’t get into that now.

Despite the fact that – much like its central Creature – the novel mashes together various preoccupations, it also felt like a barely-edited transcription of a fever dream

Suffice it to say that it was great to hear that Word Horde, one of my favourite indie presses, has decided to dedicate an anthology to Shelley’s influential novel, amassing an army of some of the best writers working in the genres that same book has helped give rise to.

I look forward to reading and reviewing each of the stories, as I’m fairly confident that all of the 16 writers whose short fiction makes up the contents of Eternal Frankenstein has felt a similar electric charge as I have when first experiencing Mary Shelley’s work.

Because after all, it is a charge that has run through my own fiction too. My debut novel, Two, contains a somewhat hidden but nonetheless deeply embedded debt to Shelley… and I’m confident that anything else I write in the future will contain at least a shred of Frankenstein’s legacy in one way or another.

So, despite it not being a dreary November night, I look forward to unleashing my little micro-creations (aka mini-reviews) into the world very, very soon.

I hope you enjoy them too.

Watch this space.

October 1, 2016

MIBDUL | Free prints for Patreon backers

Evidence of serious Scottish humour in Edinburgh

Yep, on the off chance anyone’s listening… I’ve just come back from a very inspiring trip to the UK which encompassed a stop to the ever-gorgeous Edinburgh, as well as the not-exactly-gorgeous Scarborough.

Scarborough, however, played host to Fantasy Con by the Sea — aka this year’s edition of the British Fantasy Society’s annual celebration of fantasy and horror literature, rounded off by the Society’s prestigious awards, the most notable of which were this year snatched up the likes of Naomi Novik, Catriona Ward and Ellen Datlow.

I’ll be blogging more about the trip in general (and the Con in particular) very soon, but first, I’d like to big up a more immediate creative concern.

*

So, we’re doing a six-issue comic book series called MIBDUL.

(‘We’ being myself and the awesome artist Inez Kristina)

We’ve got a Patreon page running.

And we’re offering free prints on it RIGHT NOW.

You can follow this here link to find out all about the giveaway, and root around the very same Patreon page for more information on the comic itself, which will be Malta’s very first serialized comic, and should also be a hoot for fans of Star Wars, HP Lovecraft, Guillermo del Toro and all those concerned with the alarming facts of the Anthropocene Era (no, really).

You’ve got until Tuesday to avail yourself of the free prints offer, but I do so hope you will also support us in the long run.

Watch this space for more… of Mibdul, and other stuff too.

September 13, 2016

Do it for yourself | T.E. Grau | Interview

T.E. Grau

When did you first realise that you wanted to start writing fiction, and did you act on this impulse immediately?

From as far back as I can remember, I had an interest in writing, and starting in my early teens, I fostered a nebulous, long-range plan for engaging in the serious authorship of fiction at some unspecified date. But instead of hunkering down and just doing that, I spent decades dancing around the edge of the well, writing everything else but fiction, including music journalism, review work, two different humor columns, tech writing, ghost writing, and dozens of intensely mediocre screenplays.

I think what held me back was I thought I needed to write a novel to be an author, and I didn’t have any ideas for a novel that were worth a damn, other than some bullshit pseudo-Hunter Thompson tale about an American drifting to China to document the last vestige of the American Dream on the opposite end of the world. It would have been awful.

At the tail end of 2009, while I was writing one of those intensely mediocre screenplays – which just happened to be for a horror film for which I was brought in to “add in some Lovecraftian elements,” as I had read and greatly enjoyed HPL’s work back in college – my wife Ivy changed the course of my creative life forever. She’d read some of my scripts, and enjoyed some of the exposition (overly long as it was), but also saw that the medium wasn’t a good match on either end.

HP Lovecraft

Finally, as I was complaining about yet another round of ridiculous producers’ notes and re-writes on a script that probably wasn’t going to get made anyway, she said, “Why don’t you just stop with this screenwriting and write fiction?” That was it. No one had ever asked me that question before. Not in the 11 years I’d written scripts, nor the decade before while I’d written everything else, futzing around for local arts magazines and live music journals. The simplicity of her question – which hit my ears as a statement – was astounding. That I could just walk away from a medium into which I’d invested over a decade of my creative life but also grown to loathe, and finally pursue something that I’d always dreamed of doing. I “quit” screenwriting that very day, and Hollywood somehow plodded onward without me.

While reading and researching Lovecraft’s work for the script I’d just been working on, I’d discovered that there was such a thing as “Lovecraftian fiction,” stories written as pastiche, inspired by, and/or set in the universe created by H.P. Lovecraft. I had no idea this was a thing. But poking around a bit more, I found out that there were anthologies looking for short stories of Lovecraftian fiction, and that an editor (and RPG icon) by the name of Kevin Ross was looking for stories for his antho Dead But Dreaming 2, to be published by Miskatonic River Press (Tom Lynch’s outfit).

I think I’m a better writer because my journey to prose took so long, during which time I wrote for very few readers in a wide range of styles

I saw that as my shot to break in. I didn’t need to write a novel to be a prose writer. I could write a short story, and ease my way into the fiction game. Find out if I have a knack for it, and then see what happens. I started writing ‘Transmission’, then started writing ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’ almost simultaneously. I pitched both to Kevin, and he vibed better with ‘Transmission’, so I finished the story and sent it to him, and he accepted it. My first completed, and purchased, piece of fiction. I held back ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’ for five years, and first published it in The Nameless Dark: A Collection, even though it was initially written in early 2010.

So, my journey to prose was a long time coming, but I think I’m a better writer because it took so long, during which time I wrote for very few readers in a wide range of styles, and mainly due to the constant rejection one faces as a screenwriter. In film (not television), the writers are on the very bottom rung, and receive no deference and very little respect for their integral contribution to the content-making process.

That was important for me to experience, if only to get over myself and realize my fingers don’t weave gold with every keystroke. Ivy working with me as my editor was the other important factor, allowing me to finally understand that the fine tuning is just as or more important than the initial burst of creativity. That not every sentence (or paragraph or page) is precious and sacred. Defensive writers aren’t great writers. Confident writers kill their babies, because they’ll always make more. She taught me that, and I owe her everything because of it.

Why is horror such an appealing genre for you, both as a reader and writer?

I think you’re either born a person who digs the darkness or you’re not. And I don’t necessarily mean people who play Halloween dress-up every day, favor goth fashion, live as wanna-be vampires, practice Satanism, or something similar.

That’s cool and all, if that floats your boat, but what I’m talking about is someone who has a genuine interest, fondness, and deep affection for things that reflect a melancholy, a gloom, a doom, a general decay and reflection of mortality or pessimism. Things that are just a bit askew from the norm. The incomprehensible or the unexplainable. Liminal places of abandonment and decay. Rain clouds and fog. Desolate fields. Ruined buildings and oddly constructed houses. The vastness of outer space. Magnolias draped in Spanish moss. Mausoleums. Subterranean places. Attics. Abandoned barns and industrial sites. Vast stretches of trees. Cheap carnivals. Ancient caves at the bottom of the sea. The beautifully grotesque and the (Big G) Gothic.

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli

These are the essential salts, the foundation elements, of horror and fantastical fiction. It either appeals to a person or it doesn’t. You can’t force it, you can’t fake it (although some do try).

And while I’m a generally upbeat and affable person, my mind and curiosity and sense of wonder call out to those things, and when I encounter them, while most would be saddened or creeped-out or uncomfortable, they make me happy and content.

I feel at home. That’s what draws me to horror literature, and to those who can capture this sense of gloomy atmospherics, dread, and impending doom in the stories they write. There’s nothing quite like that. It’s a true power.

There are many definitions of the ‘weird fiction’ genre (which you’re also associated with). What’s yours?

I get uncomfortable with the various labels going around for what I like to call “dark fiction,” as I think people spend too much time trying to create then box-up subgenres of fiction for discussion or marketing purposes, or just for “team-ism,” which is rarely productive or positive. But I do like the term “weird fiction,” as it nods to the late 19th and early 20th century authors, including all of those amazing pulp writers, who added so much to fantastical fiction.

Weird fiction to me is also defined by a literary streak, a core of elegance and elevated prose, which usually brings with it a sense of restraint in terms of blood, gore, or even death

Weird fiction to me is work of writing that introduces the unexplained – and usually unexplainable – into our rational world. It can – and often is – laced with the scientific, the religious, the historic, and the cosmic, taking real world facts and beliefs and twisting them just a bit, then setting them back on the shelf to distract our eye, as something just doesn’t seem right about them anymore. It’s peeling back a common facade and finding something unexpected and unknown underneath. It’s the odd, the uncanny. The bizarre.

Also, and this is just a personal opinion, but weird fiction to me is also defined by a literary streak, a core of elegance and elevated prose, which usually brings with it a sense of restraint in terms of blood, gore, or even death. Weird fiction can be quite subtle, but no less impactful in terms of unsettling a reader.

Would you agree that Clive Barker and Nathan Ballingrud are among the most powerful influences on the stories collected in your debut collection, The Nameless Dark? If so, why?

Clive Barker certainly isn’t an influence, as I had never read any Barker until the stories for The Nameless Dark were either finished and published in other places, or already plotted out. I didn’t read Baker during his heyday in the 80s, as I was still geeking out over high fantasy and sword & sorcery. The closest I came to horror was Conan books.

Nathan’s work isn’t so much an influence either (as, similar to Barker, most of my stories for my collection were already either finished or plotted when I read his work for the first time in North American Lake Monsters), but his writing was and is very important to me in terms of what the genre of dark/horror/weird fiction is capable of in this new century.

No one writes with more honesty, and can inspire more discomfort, than Nathan Ballingrud

So, in many ways, he’s not an influence so much as an inspiration, as the fearless exploration of guilt, shame, embarrassment, and generally horrible behavior that lies at the heart of many of his stories hit me like discovering a new color. I was floored when I read his collection. Still am. No one writes with more honesty, and can inspire more discomfort, than Nathan Ballingrud. He’s also a genuinely scary writer, meaning he writes things that scare or disturb me. I rarely experience that reaction when reading anyone’s work.

Barker is great (particularly his shorter work, like ‘In the Hills, the Cities’), and his Hellraiser universe is a horror staple (co-opted by Hollywood), but in many ways, I think Ballingrud is a superior writer to Barker, although I understand it’s difficult to compare based on time periods and conventions of the respective eras.

Long term, and deep down into my marrow, I’m probably more influenced by Hunter S. Thompson, Vonnegut, and Beatnik writers than anyone in horror fiction, although Lovecraft certainly influenced several stories expressly written for Lovecraftian anthologies, some of which ended up in The Nameless Dark.

The figure of Lovecraft looms over many of the stories too. Does the fact that there are plenty of Lovecraftian ‘markets’ open at any given time play a part in that? Or have you always been attracted to the core of Lovecraft’s work?

I covered a bit of this above, as Lovecraftian fiction was my entry into prose writing, and horror writing in particular. Regardless of how I feel about him personally, his work got me into writing fiction, which literally changed my creative life, and I’m grateful that he drew from and coalesced many of his influences (Bierce, Poe, Dunsany, Chambers, etc.) into the multiverse and mythos he created.

Cthulhu in R’lyeh by jeinu

What originally drew me into his work was his sense of cold cosmicism, and a universe that is far more vast and malevolent and uninterested in our existence than our puny, needy human intellect can comprehend. There is no devil, no angels, no bearded man pulling the strings. There are no strings. Just endless voids, with the occasional Outer God and Great Old One brushing against our reality just long enough to influence primal cultures, establish secretive and murderous cults, and burst minds by their very existence. I loved this. It was very dark and menacing, very secret history and cryptozoological.

Growing up in a staunch, Evangelical Christian home, the stuff I was fed in church always chaffed at the back of my lizard brain. Stumbling across Lovecraft’s outlook on the universe was a revelation, and a breath of fresh, clean, pessimistic air. I was hooked instantly.

My most recent, current, and upcoming work doesn’t and won’t contain nearly the level of Lovecraftian influence, but his work will always feature somewhere in my writing, especially in my Salt Creek stories, a novel for which I’m slowly putting together.

A satirical edge is also present in a number of the stories, mainly focused on certain aspects of American culture that seem to irk you. Were there axes you needed to grind before you set out writing some of these stories?

Before writing fiction, I wrote comedy for years, in various mediums with varying levels of success. I’ve been doing it much longer than writing dark fiction, so humor or satire is going to naturally bleed into my writing where appropriate (and maybe where it’s not).

I do have a lot of frustration, and even some bitterness, about various aspects of American culture

I’ve never thought of my satirical viewpoints as grinding axes, per se, but I do have a lot of frustration, and even some bitterness, about various aspects of American culture, and humanity itself. Hyper-religiosity, racism, misogyny, stinginess, greed, bad parenting, predation, xenophobia, and just general shittiness to others gather at the top of a very long list of grievances against my species.

Okay on second though, I’m grinding several axes. I’d guess dozens of axes are being ground at any one given time, depending on how many stories I’m working on at the same time.

Could you tell us something about your upcoming novella, They Don’t Come Home Anymore? How would you say it builds on your previous work?

I always have a hard time summing up the novella without giving anything away, but here goes a weaksauce attempt: It’s a story about teenage obsession, conformity, parenting, class, and illness providing a backdrop for a somewhat jaundiced, slightly different take on the contemporary vampire tale.

I’m not sure how or if it does build on my previous work, although it is set from the POV of a teenage girl and follows her around in the world. In this way, it reminds me a bit of ‘Tubby’s Big Swim’, as it includes a bit of geographical wandering, which set the plot framework of ‘Tubby’.

I see it as something I’ve never done before (and probably won’t do again), marking my first and probably last vampire tale. Also, it’s my longest piece to date, which shows some building on my previous work.

And the cover – featuring artwork by Candice Tripp and cover design by Ives Hovanessian – is an absolutely stunner. I count myself incredibly fortunate to feature such a cover as the calling card for the novella. Candice is doing the artwork for my second collection, and we have another project in the works, as well. Crossing my fingers that I’ll be working with her for many years to come.

And finally… what advice would you give to writers keen to break into the weird fiction and/or horror scenes in particular?

First of all, write what you want to write. Truly. Honestly. Dig down deep, cast your gaze out as far as you can, and get it all out. Question everything, follow all leads. Don’t worry about genre or market or anything out of your control. Until you get paid for it as an employee with a parking pass, bathroom key, and benefits, don’t think of yourself as a “commercial writer.” Think of yourself as a writer, period, which means you write for you.

There are very few money-making fiction genres, and weird and horror fiction aren’t it

Make yourself happy and creatively satisfied, because if you’re writing weird fiction for money, a) you’ll fail in reaching your goal, because no one really makes any money, and b) your writing will come off as lackluster and passionless, which will make you even less money and lead to more failure. Don’t do that to yourself.

There are very few money-making fiction genres (and maybe one – romance/erotica, and I suppose whatever “literary fiction” is), and weird and horror fiction aren’t it. So, if you choose to write down here, crouched low in the shadows with the rest of us ghouls, do it for the right reasons. Do it for the love of the shade, the decay, the destitute and the forgotten. Do it to celebrate the beauty of the dark.

Then, get to work, and look for open markets. I’d hazard that with self publishing, online publications, and a recent proliferation of ‘zines and anthologies and fiction journals devoted to weird, horror, and dark fiction, it’s easier to place ones work these days than probably ever before in the history of written language. The markets are there. Write your best stuff and send it out.

And, in the end, if no one will publish you, publish yourself. Get your book on a shelf – YOUR shelf – and on Amazon, in indie bookstores and libraries, and build your legacy, if only for you and your loved ones. Gatekeepers are helpful, but they are not absolute. If you have the talent, the desire, and if you work your ass off, no one can hold you back from becoming a writer of whatever fiction you want to write, written however you want to write it. Very few of us are professionals, but a lot of us are writers. And there’s room for more.

Check out , and stay updated with all things Grau by visiting ‘The Cosmicomicon’

Read previous interview: Alistair Rennie

September 11, 2016

Painting a beautiful ruin | The Nameless Dark by T.E. Grau | Book Review

T.E. Grau’s debut collection The Nameless Dark is a powder keg of imagination and potential. While the rag-tag gathering of stories sometimes slides too frequently into the unhallowed and by now well-trod annals of contemporary Lovecraftiana – a testament to it being made up of various magazine and anthology contributions over the years – the writer’s voice has a rich, fresh appeal.

Mining a vein opened by the likes of Clive Barker and more recently stretched further by the pained and earthy tales of Nathan Ballingrud – who introduces Grau’s collection, confirming that he’s a writer with a baton to pass – Grau regales readers with stories that have clear horror hooks but that don’t skimp on atmosphere or psychological exposition.

And as with the abovementioned precursors and influences, a keen handling of dread is another key wrinkle in the work, making for an unsettling but immersive experience.

One of my own favourite stories from the collection would have to be ‘Return of the Prodigy’, which I had originally encountered in the Cthulhu Ftaghn! anthology from Word Horde.

Detailing a late honeymoon in a Pacific island gone wrong, the story makes full use of its exotic setting to both seduce and unsettle the reader, while also letting in yet another trademark of the author’s work: a satirical streak; the targets in this case being the dull and bigoted American middle class. The undeniable pleasure of schadenfreude looms over the story – you know these unpleasant protagonists are in for an unpleasant time, which adds a giddy excitement to the terror.

Neither is our protagonist in ‘The Screamer’ all that sympathetic and relateable – a corporate cog with very little love for his fellow man and woman beyond what he can get from them, Boyd gains a strange kind of dignity in his doomed trajectory as he follows the titular ‘scream’ that appears to infect his workplace with a siren-like call.

The regression into a submerged world of horror bubbling right under the urban sprawl is a common theme for Grau and his fellow peddlers of modern horror, and an atavistic charge – an escape from the mundane into a world of destructive bliss – is taken to its logical conclusion here.

More traditional thrills are to be found in ‘Beer and Worms’ – a brief but hard-hitting chiller consisting of nothing more except for a conversation between two friends out fishing, which by the end takes a truly sinister turn without our characters having to lift a finger to influence this very sudden and very real shift in the mood.

It’s a testament to Grau’s ability to wring horror out of any situation, which is made all the more seductive and poignant by his command of the language.

In fact, Grau’s emphatically non-minimalist style holds him in good stead throughout, and on this point he’s very much in line with Ballingrud’s approach to the genre. It’s not so much about ‘sweetening the pill’ of the horror with beautiful language. If anything, it’s rather the opposite: the language immerses you into the tale, and Grau is also careful to add texture and nuance to his characters – making the hammer fall all the harder when it does.

T.E. Grau

But the writing is also, quite simply, a pleasure to savour, and notable passages can be picked more or less at random throughout the collection. Here’s one example from ‘White Feather’ – sins of the father horror on the high seas that takes its sweet time to establish a rich historical narrative before kicking into pulpy gear:

‘Chilton held the glass to his nose, working through the alcohol and molasses down to the subtle perfume of Newtown Pippins before they were picked, smashed, and ordered to rot. Back when they first emerged as springtime buds from a lifeless branch, so full of promise. This was the aroma of his home, of a particular wind and soil that knew him from birth and yet held no judgement. He wished he were a boy again, before his father lost his leg and his mother her will, before the responsibilities of adult life solidified a legacy that was as permanent as history written by the bloody victorious. Before his last raid on Nova Scotia’.

Sometimes it does dip dangerously into style-over-substance territory, as happens with the undeniably fun but largely cosmetic ‘The Truffle Pig’ – another story written for a Word Horde anthology, this time from Tales of Jack the Ripper – which envisages the world’s first serial killer as a member of a long-standing cadre of murderers who work in what they believe to be a noble tradition.

While the language and mood is certainly on point as ever, there’s not much to the story beyond this high-concept twist. A similar problem plagues ‘Love Songs from the Hydrogen Jukebox’, in which Grau very convincingly transports us back to the golden years of the Beat Generation milieu, only to end his psychedelic journey with a Lovecraftian add-on that fans of the weird fiction genre (and the looming behemoth that is Lovecraft) will have experienced all too frequently.

But that’s not to say that riffing on Lovecraft automatically means reverting to formula, nor that Grau isn’t capable of adding something fresh to the mix.

Clear evidence of this can be found in the strongest entry in the collection, ‘Tubby’s Big Swim’. A tour de force in every sense of the word, the story does appear to have a coveted octopus at its centre, though the resemblance to Cthulhu is kept to a minimum, and Grau waits until the end to deploy it to full effect.

Instead, the bulk of the narrative concentrates on the journey of a young boy burdened with a stereotypically shitty home life, who nonetheless remains hopeful that his pursuit of the octopus in question will bring happiness… if not transcendence. The glorious kicker of Grau’s tale is that it’s largely told with a corresponding sense of wide-eyed wonder shared by Alden, our protagonist.

It’s a modern picaresque story with a Dickensian dynamic at its core, and as the beleaguered but resilient young man winds his way through vibrant, filthy streets and suspect alleyways – climaxing in a visit to an abandoned zoo – Grau paints a vivid, memorable tapestry.

The Nameless Dark is a rich and varied collection that taps into the best strands of contemporary horror fiction.

September 8, 2016

Here’s one for the misfits | Alistair Rennie | Interview

Now, the man himself steps into these unhallowed halls to make some soft — or not so soft — disturbances of his own. Chief of which is the possibility of more BleakWarrior-related craziness in the future…

Alistair Rennie

Alistair… first of all, welcome to the Soft Disturbances interview lounge. Are you sitting comfortably, and if not — why?

Not comfortably at all because you have reputation for asking difficult questions.

Okay, so… Bleakwarrior appears to have emerged from a deep simmering well of adolescent rage, bile… but also an overarching enthusiasm for life (and death). It is a violent novel about sex, and a sexy novel about violence, with the permutations of that binary being stretched to the most scintillating spectrum you can imagine (or can’t, really… not until you’ve read it). Beyond the aesthetics at play here — we’ll get to those later if you don’t mind — in terms of the psychological experience of wanting and/or needing to tell this story, was this something you’ve been wanting to get off your chest in a while?

I suppose I’ve always had a rebellious, renegade instinct that’s been with me since the day I was born – not so much as a consequence of adolescence but because of what I am. It’s something that defines me and will remain with me indefinitely – through childhood, adolescence and beyond. There’ll always be an element of rage in anything I write. But it’s mostly a force for good – energy-bringing and inspiring.

BleakWarrior partly comes from this, yes, but it also sprang, quite suddenly, out of an idea I had for writing a graphic novel. But I didn’t know any artists who could draw a full length graphic novel, so I decided to create a graphic novel using words rather than images. Part of the extreme nature of the sex and violence in BleakWarrior is a sort of literal transcription of the kind of visceral imagery you see in graphic novels.

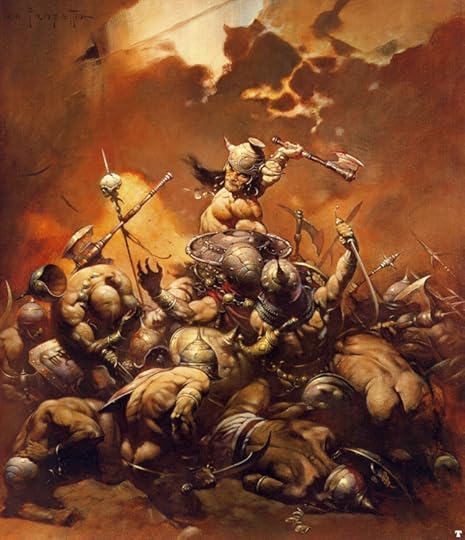

BleakWarrior by Alistair Rennie

And then I also decided to be super ambitious. I looked at my favourite examples of fantasy – Conan the Barbarian, the Elric stories, and I thought, “What can I do to follow up on those examples? How can I push this in a new direction? How can I create a character who takes things in a new direction from Elric, in the same way that Elric took things in a new direction from Conan?” Conan is quite a forlorn, lonely figure in many ways. Elric is utterly tragedian and tortured. So, I thought, “how can I create someone who’s more tragic and forlorn than they are?”

It was quite a pompous approach, but aiming high can be a good way of reaching higher.

It’s also true that a lot of the rage in BleakWarrior actually comes from what was happening at the time I started writing it – the second invasion of Iraq, the most pointless stupid war you could possibly imagine in the modern day and age. The way our governments ignored our protests, our sorrow, our pleading with them, our more vigorous demands – it was infuriating, excruciating, too much to bear.

BleakWarrior is a very misanthropic novel. This is one of the main reasons why.

And underlying all of this is something perhaps more in line with stretching back to adolescence and beyond – my abiding fascination with extremes, taking things to their furthest limits. This is more of a Romantic notion that has always appealed to me – since I was a child, I think.

‘Overindulgence’ and ‘pretentiousness’ are two of the bluntest and most commonly distributed weapons for the populace to lob at authors, and artists of every variety. BleakWarrior appears to be poised as the perfect nightmare scenario for those who would lob said weapons: being a ‘clever’ piece of genre pastiche written in a style that only an alien entity with a skewed sense of proportion would call ‘minimalist’. Did this cultural tendency ever creep up on you as you were writing, and how did you react to its gaze? And generally speaking, what do you think about the tendency to extol the minimalist and outwardly modest as more ‘worthy’?

I think I was always aware of the risk that you take when you overstep the boundaries of measured writing, subtle writing, curated writing that exercises restraint and fine-tuning.

But it was the only way to do it because the stylistic excesses are part of the whole dynamic of taking things to an extreme – where the language itself becomes a physical embodiment of the thematic content of the novel.

The style has to reflect the subject matter in order to create a uniform effectiveness, I believe, which is to ensure that the work reaches its maximum potential, as well as to underline those thematic intentions. I opted for excess, for overindulgence, in the same way that we opt for overindulgence during festive occasions. Drunken revels, fireworks, crazy dancing, festival rites, cosplay – there’s a time and place for all of them – and the principle is as true in fiction as it is in real life.

Conan the Destroyer by Frank Frazetta

Is it pretentious? Well, all fiction is pretentious in the sense that it pretends to be true. But I think if you remain true to an idea, to the vision of what you’re trying to create, then you’re doing it all with an honesty and sincerity that is the very opposite of pretentious. So I think, if you stick to the truth of the idea, then you’re likely to steer clear of accusations of pretentious overindulgence, because most readers will sense that sincerity, even if they don’t necessarily like what it’s offering them.

I also think that the idea that stylistic flamboyance, hyperbole, exaggeration are somehow equal to pretentiousness is a misunderstanding of their effectiveness as modes of expression in fiction. They are highly suitable, if not necessary, for certain types of storytelling. Fantasy and horror often benefit enormously from such a lack of restraint.

And, as for the question of applying greater value to a particular kind of writing, this is tremendously wrong-headed and can only serve to nullify the variety of writing that makes it both interesting and wonderful. To apply such values can only serve to impede any efforts towards originality that in writing – or any creative process for that matter – are necessary in order for it to thrive.

In a strange way, there’s a certain opacity to the novel too… the characters are alien (and alienating) figures with no real names, and plenty of emphasis is laid on the philosophical underpinnings of the characters and their world, with physical description being intense when it does appear, but it scarcely does. Were you ever worried that the novel won’t be ‘immersive’ enough for the reader?

There are one or two people I very much esteem who told me (in critiques of the first chapter) that they found it hard to relate to the story because the main characters weren’t human. I can understand where they’re coming from, because a part of our reading experience often depends on forming bonds with characters – or some of them – and from getting a sense of identification with them.

In this case, though, the criticism (which is entirely valid) doesn’t bother me, even while I take it on board as something to bear in mind for future work.

The reason is this: BleakWarrior is a book about outcasts, weirdos, misfits, creatures of the underworld, of the peripheries, which is also written *for* outcasts and weirdos, for people who don’t fit in, who’ve never felt comfortable with the social and political systems they’re forced to belong to as a matter of course – not through choice, but through the inevitable prevalence of the mainstream, its abysmal soap operas, its dire commercial music scenes, its hideous game shows, sterility of purpose and political idiocies, its obsession with drabness, the self-righteousness of its mediocre tastes, and the incessant glorification of its ludicrously unimaginative worldview.

BleakWarrior is a misanthropic indulgence which scorns humans for their useless inability to make life interesting.

Another question in relation to you vs the reader binary… The novel’s uniqueness makes it almost impossible to describe without lapsing into deadening cliches of the “It’s like XYZ on acid” variety. But there’s such a performative (bardic?) thrill to some of the most extreme set-pieces that it’s almost impossible not to imagine you thrilling to an audience reaction to them. So my question is, despite the novel’s extreme nature, did you in fact write it with the prospective readers in mind?

I’m always going to be a coming from a position of subversive intent, so I’m always writing for people from a cross-section of the real or imagined tribes I belong or aspire to – the Goths and punks and metalheads, the renegades, upstarts, malcontents, the nature freaks and eco warriors, the children of the underground, the activists, non-conformists and subcultural minorities of all shades.

I have to ask: where do we go from here? Is a Bleakwarrior franchise in the offing? (My gods… it would be like the Bizarro World equivalent of Game of Thrones, wouldn’t it?) Or do you want to shift gears to something to completely different?

I’ll certainly be writing more BleakWarrior and have already got a substantial amount written for what I’m very imaginatively calling BleakWarrior 2. And I’ll keep trying to put it out there.

I’ve been very fortunate, I think, because I hit upon an idea that has a lot of potential for going in all sorts of directions, and one that fills me with enthusiasm. It can be very difficult to conceive of ideas that encourage you to keep going with them, without hitting a blank wall or losing heart. So, in this case, there’s always something to add, always possibilities for expansion, always openings for new paths to take. You can imagine that having a simple rule of taking things to extremes and imposing very little restraints on anything gives you a lot of scope for having fun.

But a franchise?! The seas would have to run dry before that happened. I do have a dream that someday someone will make an animated film or series out of BleakWarrior. In fact, it would be true to say that this idea has always offered a blueprint for me to follow when writing the story. It’s part of this idea of creating a graphic novel (or anime, in this case) that is created in words rather than images. It’s an abiding principle that’s been there from the start.

On a final note, and to channel an influence very close to the essence of BleakWarrior… Alistair, what is best in life?

Red squirrels. And osprey chicks are very cuddly and vitally important for our aquatic ecosystems. But I also like being with friends; mountains, sea and sky; fleeting encounters with the Sublime; wine, *insert gender of your choice* and song; and the character of Ravenswood from Walter Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor.

That’s not what you were expecting, was it?

*

Do check in at BleakWarrior’s official website, which also features a free accompanying soundtrack to the book. Alistair Rennie’s freshly launched blog Dreadful Nights deserves a generous chunk of your time too, packed as it is with great cultural and political insights, along with a short, sharp essay on the Sword & Sorcery genres that is already appearing in various foreign-language publications. And in case you’re not already convinced that this inspired shot of crazy should make its way into your home library, do give my own review a whirl.

August 19, 2016

The Stars Are In The Gutter | Bleakwarrior by Alistair Rennie | Book Review

It’s a wonderful bonus that Alistair Rennie‘s debut novel Bleakwarrior has its own soundtrack, composed by the author himself, which you should definitely check out and listen to while you leaf through his gloriously crafted sledgehammer of a novel. But for the purposes of this review, I propose the following piece of music to set the tone. I trust it will soon become clear why this selection was made.

New Weird or weird-weird?

There is an argument to be made for Alistair Rennie’s work slotting in rather neatly into the improvised sub-genre labelled ‘The New Weird’. After all his short story, ‘The Gutter Sees The Light That Never Shines’ was the only original entry in Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s anthology The New Weird (2008), where it was presented as a sort of laboratory experiment of what’s to come — if anything is to come at all — for the genre under discussion, celebration and dissection.

Well, reams could perhaps be written about the ins-and-outs of the New Weird itself (for my part, I wrote something of a middling MA dissertation on the subject) but thankfully, Rennie went ahead and developed the germ of what lay in the original short story into a head-bangingly bizarre novel, Bleakwarrior, released earlier this year from Blood Bound Books.

Weaving in yet another short story pertaining to the same (secondary) world, which was also published under Ann Vandermeer’s watch during her all-too-brief and unceremoniously interrupted spearheading of Weird Tales, Rennie’s novel does boast a general thrust towards weirdness — but whether said weirdness can be pinned to the aesthetics of any particular genre is another thing entirely.

Bleakwarrior by Alistair Rennie (Blood Bound Books, 2016). Cover illustration by Maxwell John Hudetz

Bleakwarrior may resemble a superhero name — and he may have the abilities that vaguely match some superheroes — but the protagonist who wields it in Rennie’s novel has no alter ego. Neither do his erstwhile colleagues who populate the rather high-strung planet Rennie has concocted. In fact they boast names like Automanic, Gutter and The Light That Never Shines.

And their main mission in life is to obliterate each other with no rhyme or reason. Who needs alter egos, who needs a private life and relaxation time when endowed with such a single-minded mission? (That’s for the ‘Linear’ beings, not the ‘Meta-Warriors’ we’re concerned with right here.)

I’ll get to the main plot motor in a moment, but I’d like to dwell on this for second, because it’s important.

What Rennie captures so well is the hedonistic and atavistic thrill of having just such a brutal sense of purpose in life. The knife’s edge walk between creation and destruction — more to the point, between sex and violence — is what Rennie appears to be insatiably obsessed with. The inexorable churn of brutality that these characters engage in feels both inevitable and — operating within the hellish logic that Rennie sets up — strangely beautiful.

In lesser hands this would have felt like an adolescent indulgence: an exercise in attention-grabbing antics to an audience of lobotomised gore-hounds and their scandalised elders.

But then, the kicker.

You see, Bleakwarrior suddenly grows tired of killing people without knowing the reason why. So begins his quest; which will of course be punctuated by blood and thunder — and blood and guts — while also being placed in direct parallel to that of The Sisters of No Mercy (their name a hint at yet another aesthetic fetish that Rennie very much gives vent to in the novel’s make-up): two expert warriors slashing and fucking their way through an organ-retrieving mission in the hopes of revitalising their dearly-departed ‘Middle Sister’.

This allows Rennie to have the cake and eat it too — an often-frustrated adolescent indulgence now given full vent. By placing a philosophical conundrum at the very centre of this monstrous clusterfuck, Rennie asks you to pay attention, all the while bending your mind with the very nature of this juxtaposition. Rennie has written eloquently on what makes the Sword & Sorcery genre so special, and Bleakwarrior’s amoral world of violent supermen and women out for nothing but more violence certainly evokes that genre to some degree.

But the kicker kicks it all into crazy town. Since this is a book better experienced than explained, here’s a few extracts to give you an idea of what I’m talking about:

Whorefrost’s cock is long and thin with a remarkably bulbous head that makes it look like a bauble on the end of a stick. His testicles are disproportionately large and, like the rest of his body, hairless. More to the point, his egg-sac is teeming with semen that has an unusual potency: it is deadly cold and, to this extent, biologically devastating.

Humidity hung to the Fetid Mountains like a lubricant. The slopes were thick with an organic welter of sprawling variations of fecundity and decay. There was an aura of prototypical distinction between emergent species that took the principle of diversification to extremes that hardly seemed worth the bother.

…But what was most alluring in the appeal of the girl whose name they didn’t know was the potency of her vaginal juices that spilled over the lips of The Sisters of No Mercy with a sublime and syrupy thickness that seemed to fill their brains with infusions of erotic wonder. The taste had a weighty tang that produced an effect of mild invigoration mixed with a prolonged sense of internal melting, like being absorbed by the outer shades of a celestial aurora.

Notice how the perfectly sculpted — and it must be said, somewhat arch and archaic — prose serves as a jolting cymbal crash when combined with the XXX-rated stuff under consideration? Of course, it’s also funny, which feature Rennie exploits to full effect.

Yeah. This shit will fuck you up.

Hail, Dionysus

Bleakwarrior is literature to the Nth degree. It’s a work by someone who is hopelessly infatuated with the ‘lower’ genres but whose love and enthusiasm for them is filtered through a mature intelligence and a respect for and knowledge of the art of fiction. The obvious clue of the ‘Meta’-Warriors gives that detached postmodern element to all the craziness.

In fact, this is a novel that gets its animating friction from the simple fact that it’s at constant war with itself. It’s a novel chock-a-block with one sensationalist set piece after another — a Jacobean display of torture porn Grand Guignol that will serve as a benchmark for prose brutality for years to come — but that’s delivered through a strong narratorial voice with no interest in simply remaining in the gutter (with the Gutter). Instead Rennie wrings the experience for all that it’s worth, making sure to play with ideas as well as bodies.

But gods damn it, what will remain etched in your brain is the images. The voice will only help you take them seriously as part of an interesting new project in genre writing. One that will hopefully spawn a plethora of imitators — to say nothing of more, more, more from Rennie himself, hopefully — which will grow over the literary terrain like rancid but glorious fungus.

For Bleakwarrior is a a child of Dionysus filtered through the voice of Apollo… until you realise that it’s not Apollo at all, but a trickster god the likes of which we haven’t seen before.

In short…

This shit will fuck you up.

August 11, 2016

INTERVIEW | MOLLY TANZER & JESSE BULLINGTON | SWORDS V CTHULHU

A couple of months ago, one of the most exciting voices in weird fiction at the moment – Molly Tanzer – kindly passed on an advance review copy of Swords v Cthulhu, a new anthology she co-edited with Jesse Bullington for Stone Skin Press. Published at the tail-end of July, the 22-story-strong collection mashes ‘swift-bladed action’ with HP Lovecraft’s cephalopod alien-cum-existential dread milieu to great effect, to the point where I was inspired to review every single story in the anthology. Now, I (virtually) sit down for a chat with Molly and Jesse about the ins and outs of the anthology, and what it was about the concept that really got them going.

Lovecraft anthologies are a dime a dozen these days. How did you set about to make Swords v Cthulhu as fresh as possible?

Jesse Bullington: It always comes back to the authors, doesn’t it? So long as you have a wide array of interesting voices engaged with the project you can make any subject feel fresh and exciting. To that end we knew from the beginning that in addition to inviting certain authors we wanted an open reading period for submissions – some elements you know you need from the very start, but others you don’t recognize until you see them.

Molly Tanzer: I’d like to add that when it came to soliciting authors, we wanted a mix of people known for their S&S, as well as authors who write horror or fantasy, just to keep the tone different piece to piece. We also found a delightful amount in the slush, that was super-hard, just so many unique and interesting twists, that it was difficult to make calls sometimes. I was really impressed by the range and talent we acquired one way or the other for this book.

The world of genre small press can be dangerously insular: a tight-knit community where – thanks to the internet – everyone knows everybody else. How did you avoid the pitfalls of what could amount to nepotism when selecting the tales in the anthology?

MT: I wasn’t too worried about it. For one thing, we held open submissions, and took a ton from the slush; for another, we had a lot of material to choose from, so the competition was pretty fierce. We rejected friends and accepted people we’d never heard of; we also accepted friends and rejected strangers. Sure, we know a lot of the folks we accepted, but I think the individual stories’ quality speaks for itself.

JB: Yeah, and then there’s the fact that when you’re working as a pro writer and editor you make a lot of friends because you love their work. The vast majority of the friendships I’ve made in this industry have grown out of an appreciation of an individual’s writing, so if I were to never publish someone I’ve come to know personally I’d be cutting myself off from many of my favorite contemporary writers.

Molly Tanzer

The predecessor to Swords v Cthulhu within the Stone Skin Press stable was Shotguns v Cthulhu. With their in-yer-face mashing together of genre-furniture with Lovecraftiana, these titles suggest pulpy fun above all: they’re great attention-grabbers. Do you think your collection in particular offers something more than just pulpy comfort reads, however?

JB: Before saying anything about our anthology I think it’s worth noting that Shotguns v Cthulhu was far from a straightforward action anthology. Editor Robin D. Laws had some fast and fun pulp yarns in there, sure, but there are plenty of brains to go with the brawn (Ekaterina Sedia’s weird wartime tale and Nick Mamatas’s kung fu headfuck immediately jump to mind, for example). So with Swords v Cthulhu Molly and I were very much trying to live up to Robin’s precedent of providing depth, variety, and style as well as action and monsters…but plenty of those, too!

MT: Pulp and comfort reads are two things that are very individual and difficult to define—like pornography, you know it when you see it. I mean, many people probably find the 1982 Conan the Barbarian pulpy, but every time I watch it I’m moved and reminded of what’s important in life. So, whether the book provides more than pulpy comfort seems like something for readers and critics to decide, more than its editors.

Is ‘swift-bladed action’ something you seek out in your own reading? Are you fans of swords-and-sorcery and the kind of historical fiction that the authors in this anthology draw from, and if so, what would you say are its main pleasures?

MT: I read a little of everything, but yes, fantasy and historical fiction make up a large part of it. I’m actually doing a series over on Pornokitsch right now, with Silvia Moreno-Garcia, where I’m reading (and she’s re-reading) the first four Gor novels. In the latest of those, there’s a war between hyper-intelligent, technologically advanced praying mantises and cloned human slaves armed swords and makeshift spears. That sounds far more awesome than what is actually happening in Priest-Kings of Gor, but that’s neither here nor there. Anyway, when I’m done with that, the next thing in line is Amy Stewart’s Lady Cop Makes Trouble, so yeah, I was very pleased to see our authors draw on everything from the English Civil War to far-flung planets more metal than any mind of man could comprehend.

I suppose historical and fantastical fiction provide pleasures both similar and different to any well-written novel or short story—that of stepping outside one’s life for a few moments to experience another. Fantasy gives us barbarians and/or dragons and/or wizards and/or whatever; historical fiction provides us fancy dresses and/or interesting archaic weapons and/or insight into our past, but to me it still comes down to getting acquainted with characters and seeing what they’ll do when stuff happens to them, no matter what sort of stuff it is.

JB: I also read a ton of fantastical and historical fiction, and for the same reasons. I’m in agreement on the source of much of their appeal, too – the only thing I’d add is that I think when we read fantasy or historical fictions we often see the conflicts as being far more dramatic but also more clear-cut than those in our own lives. Even though no sane person would want to actually solve their problems with a sword, it can certainly be an appealing daydream otherwise!

Jesse Bullington

The 22 stories that comprise this anthology are an eclectic bunch, to be sure. But we’d be lying if we don’t say that some recurring themes, motifs and general narrative set-ups didn’t stick out: the colonial milieu in both Ben Stewart and A. Scott Glancy’s story, for example, along with the literary revisionism of Natania Barron and Carrie Vaughn. Did you engineer these commonalities yourself, when you were selecting the stories that would finally end up in the anthology? And if not, why do you think authors were drawn to these motifs in large numbers? That is, what do you think it is about the ‘Swords v Cthulhu’ brief that inspires writers to chase these particular storytelling elements?

JB: We selected individual stories based on their own merits, and of course our taste as editors. As for why certain themes and motifs appealed to the contributors, I’m sure it varied from individual to individual and I’m reluctant to speak on behalf of anyone but myself. Sorry if that sounds like a cop-out!

MT: Jesse and I spent quite a bit of time mulling over our submission guidelines because we wanted to make it obvious what we were looking for. We had a vision in mind for the book, after all! Given our mutual love of fantasy and historical fiction, we suggested those approaches (among others).

Given that you’re both writers of fiction in your own rights, what kind of creative kick does editing an anthology give you that writing fiction from scratch can’t?

MT: Well, the pleasures of curatorship, I suppose. Sure, when I write a story or a novel, I’m arranging and compiling and creating, which all overlap with editing, but it’s internal rather than external. Doing that for others was a new thrill for me – this was my first anthology – but turning a skill set over and looking at it in a new way was something I enjoyed very much.

JB: Editing someone else’s fiction is an entirely different animal than editing your own, and if it affords a special kick I suppose it’s being able to identify areas for improvement without actually having to fix them yourself!

Do you think the small press genre fiction community is in a healthy place at the moment? What advice would you give to writers who are just starting out, or trying to break into the scene in which you guys are active?

MT: This is a hard one. Everyone in publishing, whether they’re with a small press or are publishing with the Big 4, can have only a keyhole perspective, though of course the size of that keyhole is highly variable. I think that the small press scene can be a great and vibrant place full of the weirder stuff you might not see coming out elsewhere. This isn’t to say big publishers won’t take on risky books, but… you see the problem here! Publishing is huge, everyone has their own perspective, and you can’t say much without massively qualifying it.

As to writers trying to break into the scene… what I have to say isn’t going to be too different than anyone else. Value yourself and your writing. Submit to the markets you read, and furthermore, submit strategically, either top-down or best-for-you-first. Be wary of promises that seem too good to be true, and ask for advice if and when you need it, preferably from people who you know are reliable, and who have similar careers to what you want for yourself, or broad experience.

JB: Haha, yeah, I don’t know if I’m in any position to comment on the state of any community! There are a lot of great books coming out through a lot of different small presses, so that’s good, right? Beyond that I think I’ll just second Molly’s assessment.

Advice for starting writers is an easier answer: stop spending all your time reading goddamn advice about writing and just fucking write! Do it all the time! Why are you still reading this interview when you could be writing? Wriiiiiiite!

Now if only I could follow my own advice…

What’s next for you?

MT: A few things … a standalone reprint of my novella Rumbullion: An Apostrophe will be published this year (it was previously collected in my out-of-print collection Rumbullion and Other Liminial Libations), and next year will see the publication of my second anthology, a cocktails-and-flash fiction book called Mixed Up!, which I’m co-editing with Nick Mamatas. Also, either late next year or early 2018 my novel Creatures of Will and Temper will be published, which is a sort of feminist retelling of The Picture of Dorian Gray, but with epee fencing and diabolism and sisters arguing with one another.

JB: I’m currently completing revisions on the concluding novel in my Crimson Empire trilogy, which has been coming out under the pen name Alex Marshall. It’s a sprawling work of dark fantasy that should be solidly in the wheelhouse of anyone who appreciated Swords v Cthulhu…I hope!

Check out Swords v Cthulhu on the Stone Skin Press site. Meanwhile, click here to read the reviews of the 22 individual stories in the collection.

July 24, 2016

Swords v Cthulhu read-a-thon | Table of Contents

From mid-June till now, I dedicated some time to reviewing Swords v Cthulhu, a freshly-released anthology of ‘swift bladed action’ set against the backdrop of HP Lovecraft’s literary legacy and the monsters + existential dread that beset it, edited by Molly Tanzer and Jesse Bullington, and published by Stone Skin Press. Here’s the linkstorm to all of the entries. Enjoy!

Non Omnis Moriar by Michael Cisco

The Lady of Shalott by Carrie Vaughn

St Baboloki’s Hymn for Lost Girls by L. Lark

The Dan no Uchi Horror by Remy Nakamura

The Savage Angela in: The Beast in its Tunnels by John Langan

The Dreamers of Alamoi by Jeremiah Tolbert

Trespassers by A. Scott Glancy

The Children of Yig by John Hornor Jacobs

BUMPER EDITION: Carson, Wilson, Grey

BUMPER EDITION: Stewart, Wagner

Without Within by Jonathan L. Howard

Daughter of the Drifting by Jason Heller

The Matter of Aude by Natania Barron

The Living, Vengeant Stars by E. Catherine Tobler

Of All Possible Worlds by Eneasz Brodski

The Final Gift of Zhuge Liang by Laurie Tom