Teodor Reljic's Blog, page 11

November 21, 2016

Feel this: Sense8 and the power of pulp

The Netflix series Sense8 is not a perfect show. First of all, its ambitious — and doggedly international — scope exposes it to some infelicitous short-cuts. Perhaps the least problematic of these is a recourse to wooden, melodramatic dialogue. Of course, there’s little time for nuance when you have to cut to characters spanning various continents in any given episode, and when these same characters have to project their qualms and dramas as quickly and forcefully as possible before their allotted time is up.

With respect to one particular mini-universe in this ensemble of eight — that of the Mexican B-movie and telenovela hunk Lito (Miguel Ángel Silvestre) — this has the unintentionally amusing effect of blurring the lines between the deliberately corny dialogue Lito spouts on his day job (which we’re clearly meant to laugh at) and the dialogue of the show proper, which is quite often just as cringe-worthy in its earnestness.

Make believe: Lito (Miguel Angel Silvestre)

But what’s more problematic is the show’s unquestioning approach to national stereotypes; again, something we can almost justify as a necessity due to time constrains but only up to a point, especially in light of the fact that a ‘right-on’ message of interconnectedness and empathy also appears to be the raison d’etre of the show.

And so Wolfgang (Max Riemelt), the German sensate, reminds us that his folk are not as prudish about nudity as the rest of the world, the Icelandic Riley (Tuppence Middleton), not only has a fey look and predilection towards music (here’s to Bjork and Sigur Ros!), but also has a ‘hex’ hanging over her head — tapping into the Nordic ‘forest elf’ stereotype.

Worlds apart: Doona Bae and Aml Ameen

Meanwhile, the South Korean big business heiress Sun (Doona Bae) is an expert in martial arts, while the Nigerian van driver Capheus (Aml Ameen) has to remain plucky and resourceful in the wake of his mother’s AIDS diagnosis and the country’s incorrigible drive towards corruption and violent crime. And the Mumbai-based chemist Kala (Tina Desai) is inevitably rent apart between tradition and modernity, as her devout Hindu beliefs clash with the familial pedigree of (the undeniably charming and decent) man she’s about to marry, but whom she doesn’t love.

However, there’s two American characters — the ‘one per country’ quota doesn’t apply to them, it seems — and while Will (Brian J. Smith) doesn’t stray too far from an ingrained blue collar cop going the extra mile trope, Nomi (Jamie Clayton) is a transgender hacktivist who clearly gave space to the show’s co-creators — the Wachowski sisters — to explore themes dear to them.

Damsel (temporarily) in distress: Jamie Clayton as Nomi

Taken together, Will and Nomi represent a wide-enough spectrum of American society, at least when compared to the show’s otherwise piecemeal approach to depicting the social context of their globe-scattered cast. Will is the son of a cop in his twilight years, with a clearly working class pedigree which he’s chosen to carry through, while Nomi — formerly ‘Michael’ — comes from an upper middle class stock whose comforts, conventions and trappings she has had no choice but to abandon in pursuit of her own happiness.

But at the same time, it would be disingenuous to accuse the Wachowski sisters and their co-writer on the show, the veteran J. Michael Straczynski, of chauvinism. For flawed as it may be in parts, the length of its reach can only be admired, and its fitting together of disparate characters and emotional journeys shows off a masterful exploitation of the serialised storytelling idiom.

The Matrix has you, but it’s not what you think

For better or for worse, The Matrix trilogy remains the hallmark of the Wachowskis’ career. The Keanu Reeves-starring cyberpunk pastiche was one of those ‘once in a generation’ things: a pair of barely-tested filmmakers were given the chance to realise an ambitious (that word will keep popping up) project in a move that paid off handsomely, and in the Wachowskis’ case even resulted in the birth of a franchise.

That the Matrix sequels proved to be bloated and ultimately unsatisfying affairs has now become common knowledge, but the core of the Matrix lay in the Wachowskis’ successful harvesting of cyberpunk literature and culture in a way that renders it palatable to a new generation which — crucially — had just begun to experience the phenomenon that the genre itself prophesised: the Internet.

Will love tear us apart? Brian J. Smith and Tuppence Middleton

Fast-forward to 2015, and Sense8 refines that commentary further, by telepathically linking its global cast through a shared hallucination-cum-memory and forcing them to empathise in mind, body and soul with their fellow sensates. For us digital natives, the constant communication among the global cast does not feel at all alien: it’s no different than toggling from one browser tab to another (or better still, one chat window to another). To reinforce the point, Nomi’s partner Amanita (Freema Agyeman) actually describes the process as being like Facetime, only without any devices to facilitate it.

But the body wins

However, just like The Matrix showed us that what happens in the eponymous virtual reality has a real stake in the physical world, so Sense8 takes our for-granted approach to global communication that one step further by allowing its characters to physically inhabit and influence the world of other senseates. While this allows for other shortcuts and convenient ‘here comes the cavalry’ moments (more on that below), the Wachowskis are also clearly invested in exploring the power and impact of physicality for its own sake.

Nowhere is this made clearer than the infamous orgy scene from Episode 6, ‘Demons’. It was of course much talked-about on release for obvious reasons, and certainly makes for titillating television even on its superficial merits. But I would like to suggest that the decision to ‘bond’ the characters in this way is far from a random choice.

Sure, in a lot of ways it ticks some necessary promotional and narrative boxes — it gives the show a spike in viral visibility, and helps bring the disparate narratives together for a brief but memorable sequence — but the crescendo that it builds and the framing choices the Wachowskis employ in presenting it suggest that with this scene, the show is after more than just Game of Thrones-style clickbait-headline-grabbing.

Zoning in on the characters already engaged in some form of physical activity — the bulk of it being sex, of course, but Will gets in on the action simply by dint of spending some time at the gym, while the oft-nude Wolfgang ‘hosts’ the entire party at a sauna — the scene ramps up the passion not by focusing on pornographic money shots and a linear drive towards orgasm. Instead, it makes it a point to concentrate on the pleasure of all involved, and the Wachowskis are careful to give an identity and purpose to each of the participants.

To bring the point home that this is about the body first and foremost, and not about sex in particular, poor Will has to keep a straight face while lifting weights at the gym when he suddenly finds himself driven to orgasm by his newfound telekinetic brother-and-sisterhood.

Conflicted: Tina Desai

And the fact that not all the sensates participate in the scene is further evidence that this is not just a cheap attempt to get a rise out of the audience. Because at that point in the story, Riley, Sun and Kala aren’t in the right emotional place to partake in a joyous orgy.

The virginal Kala — crucially, she waves off sex ed advice from a fussy aunt by invoking the wisdom of “the Internet” — is fending off both an unwanted marriage and a sudden attraction to fellow sensate Wolfgang, so that participating in the orgy in which he’s present would make little sense in her arc. Sun, while certainly no stranger to physicality owing to her — subsequently quite handy — combat skills, is biding her time with monk-like patience after making a heartbreaking sacrifice for the sake of her corrupt brother.

Emotional centre: Tuppence Middleton

But while Riley’s harried state of mind — the narcotics-happy DJ has fallen on the wrong end of a drug deal gone wrong — also excludes her from the seratonin-spiking get-together, this doesn’t mean that the character, calibrated masterfully as the show’s emotional centre by a tender, raw and vivid performance from Middleton, has no claim on physicality.

But rather than sexual congress, it is childbirth that marks the most significant blot on her emotional journey, and another attention-grabbing scene depicting a live birth confirms the Wachowskis’ commitment to depicting how the physical nature of life will always trump arbitrary, remote connection.

In way, it’s almost a direct affront to a strong and consistent strand in one of the Wachowskis’ key influences for the Matrix trilogy: William Gibson’s landmark work of cyberpunk fiction, Neuromancer. In Gibson’s 1984 novel, hackers — or digital ‘cowboys’ — often derisively refer to our bodies as being simply “meat”. With Sense8, the Wachowskis appear to be determined to reinstate the value of what goes on inside our meat-containers while still operating in a genre that taps into the cyberpunk modus operandi.

Binge-watching towards empathy

But there’s another way in which the mechanism of Sense8 works to put the Wachowskis’ humanist message forward… though in this case, it’s probably Straczynski who can take the bulk of the credit for putting his vast experience of serialized writing into play.

In a way that’s both counter-intuitive and shrewd, the creative team behind Sense8 tapped into the pop culture reservoir originally opened up by Marvel Comics’ X-Men and their various multi-media iterations, by uniting a group of ‘special’ individuals under the tutelage of two sage renegades — Angelica Turing (Daryl Hannah) and Jonas Malicki (Naveen Andrews) — partly as a warning shot that their ‘kind’ is in danger, and being pursued by an errant member of their erstwhile species, ‘Whispers’ (Terrence Mann).

But for the bulk of the series, this isn’t the main motor of the narrative; it’s more like a ghostly nudge that turns into a bona fide push as the first season accelerates towards its climax. What hooks us instead are the individual narratives of the various characters, and when they interlace it feels like an added bonus.

The Great Joiner: Daryl Hannah

An ancillary — but certainly not trivial — side-effect of this structural choice is that it places all of the various questions on an almost equal emotional footing; so that a romantic discord between Lito and his beloved Hernando (Alfonso Herrera) is placed side-by-side with the comparatively much harsher realities Capheus has to contend with.

Intentional or not, this has the wonderful effect of reminding us that, while the characters day-to-day situations and national, cultural and economic context vary greatly, we can come to understand their emotional priorities and respect them accordingly.

In a world where discourse is dominated by the — sometimes blinkered — drive to “out” who is more privileged than whom, and where empathy is limited to either dry facts or sensationalised sob stories, Sense8 reminds us that the way to understand someone is to first understand that, just like you, they have a day-to-day life in which they reckon with things wonderful and mundane, life-altering and life-threatening, at nearly every turn.

Say hello to my little friend: Max Riemelt

And while the Wachowskis have left details about the sensates‘ overall purpose and mission tantalizingly open to interpretation (read: ripe for exploration in subsequent seasons of the show), perhaps one thing we can assume about the reason why they exist, is simply to remind us that it is in fact possible to tap into something resembling a common wellspring of humanity… but that taking the importance of the flesh into account — as life-giving, pleasurable, deadly and prone to death and termination as it may be — is crucial to this process.

Just like you can’t hashtag your way into social justice — as recent developments all over the world have shown — so you can’t truly appreciate the value of other human beings without doing your damnedest to quite literally walk a mile in their shoes. Or, you know, temporarily possess their body to vanquish evil henchmen thanks to the martial arts skills you happen to have, and they don’t.

The rudiments of story win, too

Of course, there’s another reason why the conceit of interconnected body-hopping humans is handy for Straczynski and the Wachowskis. To wit, it’s a clever way of legitimising deus ex machina. They don’t always get away with it: there will be points when you’ll ask yourself why a sensate manages to interfere in certain instances, and not others.

But on the whole, it works in tandem with viewer expectations and makes for great moments of catharsis. This is particularly evident in the climactic episode, where the story slots into the kind of ‘chase’ sequence that you expect from X-Men-style narratives of marginalized super-powered beings fleeing from, the confronting, those persecuting them.

Inciting incident: Daryl Hannah and Naveen Andrews

In a lot of ways, Sense8 works despite its niggles because it meshes form and content in a way that other shows don’t. The very idea of the sensates suddenly forced to come together and reckon with each of their individual life stories, and feed on each others’ abilities, works perfectly with the serialised television format, where multiple character arcs are not only possible, but actively encouraged.

It’s also clearly in line with the Wachowskis’ own ambitions, which have often resulted in stillborn feature film productions, but are finally given space to flourish in a 12-episode format.

Sense8 is a heady, febrile tumble that does suffer a few bumps and scratches on its breakneck descent. But it’s also a positive flip-side to the Wachowskis’ narrative sincerity and ambition; where their cinematic output has all too often revealed how such an approach can backfire. How a second season fares is still up in the air, of course, but the fact that its course remains touch-and-go already makes it a more exciting prospect than your usual TV fare.

Please consider donating to the Patreon page for MIBDUL — the comic book series I’m currently working on with the artist Inez Kristina.

November 18, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #11 | Scott R. Jones

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Living by Scott R. Jones

Since horror and fantasy are, broadly speaking, my favourite of the classic speculative fiction categories — while a wide berth is given to the Weird and any form of intermixing — my experience with literary sci-fi falls a bit on the lean side.

That said, the sci-fi favourites I do have, I cling to very dearly indeed, dipping in for regular re-reads. Mary Shelley’s Frankestein is actually one of them. The other is William Gibson’s pioneering work of cyberpunk fiction, Neuromancer. And despite the fact that both novels were written over a century apart from each other and that, apart from their central commitment to a science fictional set of ideas, situations and concepts, could not be further apart in tone, narrative rhythm and scope, I like to think of both of them as being complementary.

Shelley addresses the limits of bodily modification and reanimation, and problematises the notion of a creature created ex nihilo, but without the embracing context of family and community. The Creature in Shelley’s text grasps at the world outside of itself to give it meaning — it feeds on what we can widely describe as ‘culture’ to legitimise itself, but all the while its aberrant bodily shape snuffs out any chance of real belonging.

It is a tale of bodies and what they mean, and how we process or fail to process their realities: be it the Creature’s own failed — but understandable — attempts at making peace with its uniquely tormented predicament, or Victor Frankenstein’s refusal to take responsibility for his engineered progeny, largely on the basis of its physical appearance and its implications.

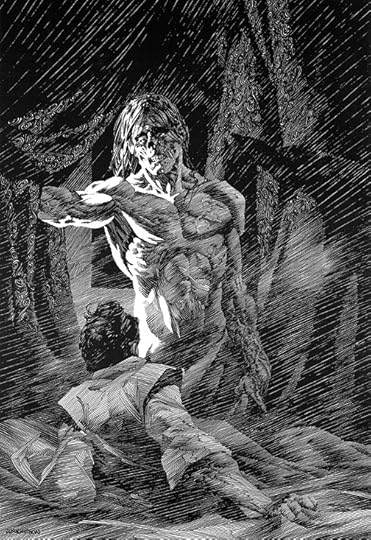

Frankenstein by Bernie Wrightson

In the end, both characters are disappointed by the fact that their physical reality doesn’t match up with the abstract dreams they have: Victor’s Creature doesn’t conform to the aesthetic decorum he may have wished to achieve with his experiment — which further cements the fact that his work is an affront to God — while the Creature’s admirable self-taught attempts at becoming intellectually and emotionally sensitive are ultimately rendered moot by the limits of its body.

The innovation of Neuromancer, on the other hand, was to circumvent the body altogether in favour of an exploration of the cybernetic singularity which has since become rote not only in fiction, but in daily life too (you’re reading this online, aren’t you?). The open hostility that some of Gibson’s characters espouse for ‘meat’ (i.e., traditional biological bodily structures) are a testament to this, and seem to suggest that Frankenstein got the ball rolling, but that the future imagined in Gibson’s model is in some ways the logical conclusion of Victor Frankenstein’s experiment.

To wit, the trick to circumvent mortality is not through some messy and pathetic attempt at stitching together dead body parts and reanimating them… the trick is to embrace the possibility of downloading and replicating your consciousness in a virtual realm that edges closer and closer to our ‘real’ one.

In his contribution to Lockhart’s anthology, Scott R. Jones happily meshes together both of these key strands in sci-fi, but in a way that they don’t, in fact, cancel each other out. In the snow-capped setting that recalls both — of course — the bookending sections of Shelley’s novel, as well as pop culture artefacts like John Carpenter’s The Thing in its depiction of rugged outliers gazing suspiciously ahead at a mysterious and dangerous mission, Scott injects his version of the Creature with both anger and agency.

Frozen waste: The Thing (1982)

The story itself is largely composed of a monologue delivered by the same stand-in for the Creature; a military experiment gone awry and who is now on a vindictive mission to find and execute its creator, Aldo Tusk of ‘Eidolon’ — a corporation or military body of some kind which has apparently OK’d Tusk’s mission to stitch together a super-soldier.

As the ‘asset’ beings its narrative, we learn that it’s made up of various body parts made to fight in unison, and the voice of the monologue is laced with a sarcastic bitterness that the Romantically pained Creature from Shelley’s original novel would never have managed. Later on, Jones adds another twist of black humour by suggesting that the Creature’s programming includes orgasmic delight at an enemy kill. This guarantees that the story has the edge and attitude normally associated with cyberpunk, but more importantly, it also means that the Creature here is a fighter, and not a subject of pity as in Shelley’s text.

It’s alive? The ‘birth’ scene from Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop (1987)

And in fact, it’s through cyberpunk ‘means’ that the hint of complete emancipation appears to suggest itself. While the beginnings of the asset’s career as a patchwork soldier are as abject as ever — they even recall Robocop‘s forced resurrection as a hybrid fighting for someone else’s agenda — the gleeful bite as she/it reveals just the programming has been circumvented is a joy to read.

A spirited and inspired mash-up of key strands of the sci-fi genre (at least from my admittedly limited POV) with a highly satisfying revenge kick to round things off.

Read previous: Martin, Falksen

November 14, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #10 | Martin, Falksen

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

The Un-Bride; or No Gods and Marxists by Anya Martin

The New Soviet Man by G.D. Falksen

You’ll forgive the slowing down in pace between the last installment of the read-a-thon and this entry; I shifted country for a few weeks and had a bit of a break in between, only to return to the island homestead to the news of America’s surprising election result.

As luck would have it — or whatever variant of luck, chance or coincidence you want to call this, given the circumstances — there is not one, but two stories in Lockhart’s anthology that riff on the history and mores of what is supposedly the polar opposite of the current US president-elect’s ideological barometer: Socialism.

However, this being an American anthology dominated by the work of American writers itching for ways to respond to Mary Shelley’s text in a way that also scratches various pop culture itches, it’s hardly surprising to discover that the stories in question don’t seek to delve into the intricacies of Socialist and Communist ideology for penetrating insights.

For the most part, both Anya Martin and G.D. Falken’s contributions to Eternal Frankenstein play on American perception of the ‘Red Scare’, attacking this perennial barnacle of US popular culture from different angles.

Martin refines her angle of attack even further, placing us in the shoes of none other than Elsa Lanchester — the English-born American actress who brought none other than the Bride of Frankenstein to life in the iconic 1935 James Whale film. It’s also a story that contains the line, “Those crazy communists had saved the brain of the daughter of Karl Marx!”, which tells you all you need to know about where Martin is going with this.

Scream Queen: Elsa Lanchester in Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

An inspired piece of tongue-in-cheek pulp, the story juggles unlikely romance and less-likely forays into body-reanimation as enabled by Soviet double-agents. What distinguishes it in narrative clip and stylistic approach is Elsa’s distinctive voice. She’s a coquettish but intelligent guide that takes the story’s many spirited twists in stride, giving us a female protagonist in a man’s world who can more than handle herself — she does it while maintaining her wit and poise too (though it must be said, she’d hardly a match for her own — rather formidable — mother in that regard.

G.D. Falksen — also known as the guy whose picture you find when you Google ‘Steampunk’ — takes a flintier approach. The frankly assembled third-person story has our Frankenstein figure trying his damnedest to manufacture the titular New Soviet Man away from the watchful eyes of Stalin and while ensconced in the bowels of a freezing Kazakh steppe.

Our entry point into this world is Captain Sergeyev; an uncompromising apparatchik if there ever was one, and one whose well-being we’re emotionally primed not to care about too much, dour little customer that he is. Which is good, because while Falksen metes out what could be considered something of a predictable denouement for him, it’s falls on the rather pleasurable side when it does arrive.

Karel Roden in Frankenstein’s Army (2013)

A central moment in the story — in which the Doctor suggests that going from Fascist to Communist fanatic is more or less as easy a flicking a switch, for him — reminded me of a similar quote in the otherwise gleefully pulpy Frankenstein’s Army (2013); which takes the more traditional route of having Frankenstein as Mengele (rather than a renegade Communist weird scientist).

If nothing else, both Martin and Falksen prove that war and its fallout is ripe pickings for Frankenstein stories, with many corpses vulnerable for desecration by the equally numerous ideological nut-jobs ready to tinker with them… while the still-living attempt their Creature’s shamble back into normal life with varying degrees of success.

James Whale himself certainly knew it.

Read previous: Betty Rocksteady

October 31, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #9 | Betty Rocksteady

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Postpartum by Betty Rocksteady

And so, Ross E. Lockhart impresses me with his sharp editorial skills once again. Just last review, I was speaking about how we in fact don’t speak about Frankenstein as a book about artistic creation all that often, spurred on by what seemed to be a subtle treatment of that very same strand in Michael Griffin’s novelette ‘The Human Alchemy’.

But turn the pages over to the next story on the TOC — Betty Rocksteady’s ‘Postpartum’ — and bang! there it is. Nothing subtle about it: Rocksteady decides to not only place that metaphor at the front and centre, but to make it the main motivating engine of her contribution to Lockhart’s anthology.

However, the title also suggests a more pained and universal fact of human life, and one that will also remind us of another key element in the fabric of Mary Shelley’s original text. Rocksteady’s protagonist is a reluctant teenage mother who has lost her sweetheart soon after their baby — the poor, unfairly derided Timmy — is born, and her first-person narration does very little to endear us to her plight beyond the fundamental misery, and recent tragedy, that underlies her existence.

Still from Hannibal, ‘Trou Normand’ (Season 1, Episode 9)

Rocksteady uses this to create suspense — the central artistic creation could easily be something out of NBC’s Hannibal — but the idea of a mother rejecting her child of course also recalls Victor Frankenstein’s heart-breaking (and instant) rejection of his own Creature.

But where Victor Frankenstein is all neurotic self-justification in his own version of events — really, it reaches Humbert Humbert like proportions at times — Rocksteady’s teenage narrator has no such qualms, coming across as bratty at best and downright spiteful at worst. This only increases the aforementioned suspense, because in that mental state, our otherwise powerless (psychically and economically) protagonist gains an unsettling degree of amoral freedom.

Rocksteady’s story is at its most affecting when the emotional satisfaction of creating art is being detailed: the only real relief that our narrator gets, and one that his sanctioned by her doting mother, who knows full well that art is her only real method of release. The trouble is that the raw matter used in the act of creation preclude the essential beauty of the idea, much like Victor Frankenstein’s ambitions to create life ex nihilo lose their luster when confronted with the groaning hodge-podge Creature springing into life and demanding to be recognised and loved.

A taboo-prodding tale with a shocking ending that’s fully earned.

Read previous: Michael Griffin

October 28, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #8 | Michael Griffin

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

The Human Alchemy by Michael Griffin

We rarely speak of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as being about the angst related to artistic creation, and instead grasp at more solid metaphors. Understandably enough, received wisdom has it that this is first and foremost a parable warning against scientific hubris on the thematic level, and emotionally, it resonates with us thanks to the undeniable pathos we feel towards the creature: rejected by a father who only half wanted him, with no reference points in a world that wants nothing to do with him.

So I was glad to see that Michael Griffin’s creepy but complex tale of a successful pair of surgeons — with otherwise also picks up on the ‘standard’ intertextual cues stemming from Shelley’s original text — also pitches its Frankenstenian couple, Reysa and Magnus Berg, as frustrated creatives looking to satisfy their unconventional cravings in a world that has yet to — ethically as well as aesthetically — catch up with their tastes and ambitions.

In the case of Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein’s initial revulsion at the Creature he’s made could find a direct corollary in the way most young writers — or artists of any stripe — would view their juvenilia. “I expected to create something at least as beautiful as the work of the forebears in the field that I admire,” they think to themselves as they grimace at that first draft, or that hesitantly completed painting, “what the fuck is this shit?!”. And in it goes into the proverbial fire.

Pedro Almodovar’s own take on Frankenstenian surgeons: The Skin I Live In (2011)

But Reysa and Magnus are not young: Aurye is, and though their wine-soaked gathering at the rich couple’s mountaintop castle may suggest all the trappings of a cliche seduction into a three-way, this mundane idea is dispensed with fairly quickly. In fact, the couple reject all mundane ideas suggested or imposed by society, a dogma whose limits are tested by this increasingly disconcerting, but equally sensitive and intelligent, contribution to the anthology.

And the way Griffin manages to walk this tightrope is, in fact, by couching the couple’s past history and future dreams in the most precise, and even reasonable, discourse. As one example, let’s get back to the artistic creativity metaphor. Midway through the story, the couple start explaining — always to Aurye, as their increasingly eager acolyte — the challenges posed by their unconventional lifestyle.

In the meantime, the story’s unsettling vortex intensifies, and Griffin actually piles all of the cosmetic details you’d expect from a Frankenstein story

Without spoiling anything, the way Reysa describes it sounds exactly like the kind of set-up a freelancing couple of any profession would face; with partners alternately sacrificing time and comfort while the other aims for their dream job, or at least helping to create a mutually beneficial situation for both based on their relevant skills.

In the meantime, the story’s unsettling vortex intensifies, and Griffin actually piles all of the cosmetic details you’d expect from a Frankenstein story: the Gothic castle, the operating table, the thunder… and a monster. But on their own, these details are now blunt: Frankenstein’s Creature is indeed eternal, yes, but the moralistic discourse about scientific ambition needs fine-tuning and updating if it is to sustain its chilling menace into the modern day.

And this is precisely what Griffin does with his two surgeons. But arguably, he completes this effect with the help of the young Aurye most of all, whose role in the drama flouts expectations in more ways than one.

An urbane and superbly structured little chiller that is intellectually engaging more than it is viscerally scary, but that is all the more rewarding for it.

Read previous: Edward Morris

October 19, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #7 | Edward Morris

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Frankenstein Triptych by Edward Morris

One of the great things about intertexuality is that it is the literary-cultural equivalent of friends bonding over shared memories; only instead of real-world happenings you’re bonding over books, music, visual art or films.

Of course, an anthology like Eternal Frankenstein practically runs on this impulse: intertextuality is its engine, and in this case it’s a particularly well-oiled one because the authors comprising it have — as far as I can tell this deep into the read-a-thon — taken on the challenge posed by Lockhart’s anthology with a canny understanding that simple pastiche (perhaps one of the ‘lower’ forms of intertextuality in practice) will not be tolerated.

But there’s fun to be had in pastiche too, and this is not lost on Edward Morris, who deliberately presents three science fictional micro-tales as his contribution to the anthology. But the pastiches here are not direct piggybacks on Shelley’s original novel, and instead take an inspired swerve into varied, forking directions.

And in the case of the first segment of this mini-anthology, ‘Dolly’, we’re not really talking about pastiche at all so much a formally interesting take on the Artificial Intelligence sub-genre. In a thread that will continue throughout Morris’ entire piece, we’re thrown into a close-third-person focus giving us a window into an unconventional perspective; in fact, it’s not even that of a ‘person’ — a particularly sophisticated doll experiencing the pangs of an existential crisis in the first instance, a mecha-warrior of sorts (we think) in the second segment, GRUNT.

Unreal cities: Morris dedicates the final segment of his piece to HR Giger

The link to Frankenstein is tangential in one sense, but very much on-point in another. In his maddened collage — which I imagine to have been a blast to write, really — Morris taps into Shelley’s essential idea of imagining what a Creature not conceived through natural means would think about, and even feel, as it tries to make sense of the world it’s been thrust into.

GRUNT is particularly inspired on this front, and the random perceptions evidenced by this poor military cog — as he/she/it witnesses the eradication of its comrades — appear confusing but in fact accumulate to paint a vivid piece that resembles poetry more than prose. It brought to mind the powerful and unique pen of Joe Pulver and, lo and behold, as the segment concludes I see that Morris in fact dedicates it to Pulver, among others.

The final segment, ‘Wir Atomkinder’ slots into more conventional formal shape but, being the confessional of a Nazi Mad Scientist that’s dedicated to the memory of HR Giger, ‘more conventional’ in this case certainly does not translate into ‘more mundane’.

Stitching together his flash fiction narratives, Morris reminds us that there’s more to the legacy of Frankenstein than scientific hubris and the dour reminder of humanity’s indifference. It’s also a story of creation — for better or for worse — and the confused by animating force on which it runs.

Read previous: Rios de la Luz

October 18, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #6 | Rios de la Luz

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Orchids by the Sea by Rios de la Luz

We can all pretty much agree that on one level — a significant one — Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a warning against scientific hubris: don’t meddle with nature, because God will punish you for encroaching on His territory. It’s to the novel’s credit that this inherently conservative thread did not sour the entire weave of the book. Instead, it’s just one animating neurosis amidst a whole army of them; as any novel penned by a preternaturally intelligent 19-year-old with a turbulent family background would be, I guess.

But in Rios de la Luz’s brief contribution to Eternal Frankenstein, the binary of Victor Frankenstein vs God is turned on its head, with Luz’s Frankenstein stand-in being presented as a Christian fanatic who believes that God himself is compelling him to breathe life into new people after stitching them into shape from the body parts of others.

The thing is, Luz’s Frankenstein — he’s never referred to by name — doesn’t believe he is “playing God” but that his victims-cum-subjects are: like the suicidal female whose brain he scoops out of the river and puts into a deliberately asexual body:

“His creation was not to have genitalia or anything resembling breasts. His creation needed no means of procreation. His creation would not be a born sinner.”

If nothing else, this shows up all of the possible dangers of any extreme position or behaviour: one extreme ends up resembling its cousin on the opposite spectrum pretty quick. So the original Frankenstein’s deep-seated concerns about the creature possibly procreating and creating more monsters of its ilk is here transferred into an urge to control sexual desire and its after-effects.

Both Shelley’s and Luz’s Frankenstein’s are men who create life only to turn away from what makes it vital in the first place: the imperfection of living beings (as made manifest by the Creature’s superficial ugliness and his shambling attempts at mimicking human life) and the effort you need to put in first before you can reap the psychological benefits of love — an effort and a degree of responsibility that Frankenstein is never willing to invest.

Thankfully — though no less tragically for it — the focus then shifts to the ‘creation’ herself, who adamantly remains a “she” despite her newfound master’s best efforts, and who escapes the creepy experimental enclosure — more bona fide Gothic than anything in Shelley’s landmark novel — to try and experience the world outside.

Her failure to find any solace is delivered with inevitability and pathos that’s far removed from the Strum und Drang of the pitchfork wielding hordes we see in more conventional representations of the Frankenstein story. The world is merciless, yes, but this is made even worse by the fact that this callousness isn’t a deliberate, calculating move made by a select few.

Instead, and like the bullying kids who thoughtlessly drive the creation to her ultimate fate in Luz’s story, it’s a casual fact embedded in us all.

We often forget how casual life is, and how lonely most of us are. We often forget to tread with caution, until it’s too late.

Read previous: Autumn Christian

October 16, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #5 | Autumn Christian

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Sewn Into Her Fingers by Autumn Christian

We’ve commented on Victor Frankenstein’s neurotic bent before; how his lack of any emotional control and steadfast denial to confront his creation and its after-effects is what propels the drama of Mary Shelley’s original novel towards its tragic conclusion.

With her contribution to Eternal Frankenstein, Autumn Christian side-steps this crucial element of Frankenstein’s character to create a story that’s by turns chilling and deeply affecting.

Told from the perspective of her Victor Frankenstein stand-in, Christian’s story is a clinical tale of a deepening obsession whose (clinical) form matches its (clinical) subject.

The story’s opening lines have him frankly confess to breathing life into the creature — a female, this time — out of pure boredom: as an extension of his day-job skill set and to be able to work on something beyond office hours. This could have been played for (dark) laughs but is instead ‘played’ for nothing at all, as we soon realise that such a flippant approach towards life is what informs our protagonist’s MO.

Bros before bots: Ex Machina

Siobhan Carroll’s story gave us Victor Frankenstein as the Marquis De Sade; doing away with the original Frankenstein’s skewed moral panic and putting sheer sadism in its place. Here the re-imagining is more muted but no less powerful for it. Christian’s protagonist isn’t a sadist, but he’s certainly missing a couple of empathy cogs. At least at the beginning of the story, what we see is the logic of the abuser being laid out to us with no frills and in no uncertain terms.

But then, something strange and wonderful happens. In another direct contrast to Shelley’s body-snatching, body-collaging man of science, our protagonist learns to embrace the creature. In a strange way — but again, also in a way that swerves away from the obvious trajectory of doomed and/or abusive scientists — the narrator’s thought process reminded me of the tiptoeing around the AI creation that we see in Ex Machina — one of my favourite movies of the past couple of years.

Unpeeling the truth: Alicia Vikander as Ava in Ex Machina (2015)

Like Nathan (Oscar Isaac) and Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) in that very 21st century take on the nub of Shelley’s text, the protagonist of Christian’s story takes time to consider the various aspects and potential of what he’s just created. But whereas Ex Machina’s Ava (Alicia Vikander) reveals herself to be something of a femme fatale by the end, Christian’s creature demands to be treated as an equal.

The protagonist’s hedged acceptance of this demand is what pushes the story into truly original territory. And, helped along by the clear-eyed, clinical style — after all, a logical choice when a scientist is telling the tale — the story makes for a disturbing but satisfying arc.

An unsettling tale that’s also strangely uplifting.

Read previous: Walters, Scandal

Please donate to our Patreon page and help us make Malta’s very first serialized comic

October 14, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #4 | Damien Angelica Walters, Tiffany Scandal

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

They Call Me Monster by Tiffany Scandal

Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice by Damien Angelica Walters

It takes guts to commission two stories with virtually identical thematic hooks in the same anthology, it takes even more sizeable viscera to place those stories exactly side-by-side in the table of contents. But Lockhart isn’t afraid to take this risky but logical leap, and with Scandals and Walter’s stories creates a logical double-bill: a teenage interlude for the Eternal Frankenstein experience, if you will.

Yes, both stories take the teenage high school experience as their springboard into — and out of — the core of Shelley’s text. While they are similar on one level — both concern themselves with a Frankenstein’s Creature teenager put together by overprotective and/or scientifically overzealous parents, who are offstage for most of the narrative — their differences are also crucial.

Scandal takes a more straightforward route (her story is also the shorter one), and has the Creature-stand in protagonist, Imelda, narrate her own experience of being bullied across various high schools as her parents move her from one town to another once the bullying gets too much to handle.

Sissy Spacek in Carrie (1976), dir. Brian De Palma

“We can’t punish the whole school,” becomes a refrain, and it serves as an equivalent to the the pitchfork-happy mobs that have become synonymous with Frankenstein stories ever since Hollywood got its mitts on Shelley’s text. While Walters builds a sense of dread through a carefully chosen framing device, Scandal pulls the rug from under our feet right at the end, mingling the satisfying arc of the coming-of-age story with something far more sinister.

In fact, Walters embraces our expectation for ‘Frankenstein stories’ from the word go: she knows that we are calibrated to expect a certain kind of arc from any take on Shelley’s text. She even throws in an extra reference for good measure: the narrator of the story — we soon catch on that we’re hearing one side of an interrogation — mentions the cult favourite film adaptation of Stephen King’s Carrie as a trigger for the grisly episode she would set in motion with her friends.

And there’s a nasty thrill to be had with how Walters dangles the carrot (or rather, bucket of pig blood) of what’s about to be recounted. Unlike Carrie, however — in which there is never any doubt about the ferocity of the bullies — this is a story of casual bullying that builds into something more malignant as it progresses. But on the other hand — and because we’re given everything from the self-justifying perspective — it’s also a reminder of how easy it is to victim-blame and scapegoat those who appear to be innately different from us.

Remember the pitchforks. They haven’t gone away.

Read previous: Siobhan Carroll

October 13, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #3 | Siobhan Carroll

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

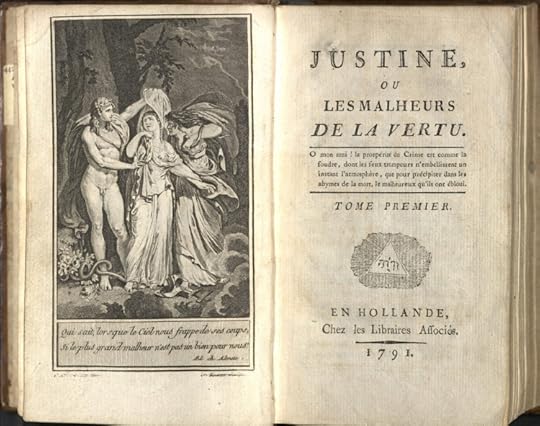

Thermidor by Siobhan Carroll

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has inspired dreams and nightmares about weird science and body modification, but let’s not forget that at the core of this much-referenced Gothic text is a tortured meditation on what it means to be human… and what it means to be its opposite.

If a creature is made from scratch with very little reference points to guide it, what does it think and feel? This is the tragedy of the Creature — a shambling creation in more ways than one, improvising his way through a makeshift life with only sporadic successes along the way.

But the Creature’s problematic physical make-up is nothing when compared to the chilly and nervous reaction of Victor Frankenstein to his creation. It shocked me to listen to Kenneth Branagh describe Victor as intrinsically a “good man”, while he talked about the thought process behind his own take on Shelley’s novel in a Charlie Rose interview, because while Frankenstein may be many things, I struggle to imagine him fitting into even the most liberal of ‘good man’ molds.

In fact, one of the main strands of the novel, to me, is Victor’s chronic inability to take responsibility for what he did — to allow himself to feel enough empathy to accept the Creature’s pain as a legitimate enough sign of his humanity.

So apart from its oft-propagated Gothic trappings and monster-movie-ready fodder, Frankenstein is a story about dehumanization, from both ends of the scale: the abjection of the creature exists as a result of Victor’s callousness, or denial of all of the things that should bind the two together in mutual understanding and love.

All this being said, Siobhan Carroll isn’t shy to indulge in a variety of cosmetic thrills that Frankenstein brings up, and neither does she resist making some delicious intertextual and historical connections to dream up her merciless little tale.

But by connecting Victor Frankenstein to the Marquis de Sade — using the name ‘Justine’ common to both Shelley’s text and Sade’s oeuvre — Carroll betrays a sensitivity to how dehumanization is what infects Victor’s project from the word go.

Like Sade’s own early novel Justine: The Misfortunes of Virtue — which takes place just at the brink of this key moment in history — Carroll’s story is saturated in the spirit of Revolutionary France, as seen over the shoulder of Justine — a character whom we could more or less equate to a Bride of Frankenstein figure. To wit: she procures still-breathing bodies for her master, who in this case is not a nervous weakling but a scientist who views torture as a necessary part of the experimental procedure.

Being a product of the very processes she helps enable Justine is in a perfect position to show how chilling lack of empathy can really be. And the story’s most intriguing passages concern her faded, ghostly rememberance of empathy past, when she sees but doesn’t feel previous pain and fails to put two and two together upon witnessing the suffering of others.

This is also a subaltern story in many ways, with Justine catching on to the Victor’s — aka the patriarchy’s — privileged and exploitative ways. But because she’s hard to sympathise with for obvious reasons, Justine’s ideological struggle makes for complex reading.

Like Shelley’s novel, Carroll’s story is about humanity at its outer limits, and throwing Sade into the mix feels like a logical extension of that literary experiment.

Read previous: Orrin Grey