Teodor Reljic's Blog, page 2

January 24, 2025

Camp Defiance: The Importance of Being Earnest (Max Webster, NT London)

Our tickets to the National Theatre‘s production of The Importance of Being Earnest happened to coincide with Donald Trump’s inauguration, and while this is the kind of coincidence one may feel smug about because the immediate effects of the atrocity may not be grazing you straight away, I will cling onto its delicious frisson regardless.

It’s not just because ANY revival of ANY Oscar Wilde play by definition stands in opposition to the global resurgence of the right-wing hegemony. It is also because, its ultimate inefficacy as direct political action aside, this particular production – headlined by Sex Education breakout star and current Doctor Who Ncuti Gatwa and directed by Max Webster – is brashly defiant about making the play’s queer subtext into text… and it approaches colourblind casting with an effortlessness that makes non-bigotry look like a delicious joy as well as an ethical obligation.

Sharon D Clarke as Lady Bracknell and Ronkẹ Adékọluẹ́jọ́ as Gwendolen Fairfax. Photo by Marc Brenner

Sharon D Clarke as Lady Bracknell and Ronkẹ Adékọluẹ́jọ́ as Gwendolen Fairfax. Photo by Marc BrennerGatwa may be the main point of attraction in terms of the latter when it comes to audiences not as clued-up to the inner workings of the London theatre scene – and I very much include myself in that comparatively unenlightened category – but it is Sharon D Clarke as Lady Bracknell who emerges as the most memorable revelation.

Anyone even remotely familiar with the play will be tempted to scream ‘d’uh!’. The archly magisterial Augusta’s lines are the most quotable in a play so littered with them they could have emerged from a camp dragon’s mountainside stash – but configuring the character as a stern Jamaican matriarch is the kind of jolt of genius that lends an air of undeniability to a reimagining – one that should silence most skeptics.

Because of course she would be that. D’uh.

Hugh Skinner as Jack Worthing and Ncuti Gatwa as Algernon Moncrieff. Photo by Marc Brenner

Hugh Skinner as Jack Worthing and Ncuti Gatwa as Algernon Moncrieff. Photo by Marc BrennerTHAT is many things, of course… and again, there’s a frisson at play – Bracknell represents the apotheosis of the ruling class in all of its status-obsessed ridiculousness, yes, but Wilde cranking the engine of snobbery up to eleven, then turning it inside-out, is what gives her an air of irresistible camp joy.

It is in that joy that the energy of the play resides, and being allowed into that sandbox where our staid assumptions about this stuff can be left at the door and we can plug into the blown-up version of that Victorian world. In fact maybe it’s not so much of a sandbox as it is a ball-pit or bouncy castle – the brightly coloured production design certainly welcomes the metaphor.

Eliza Scanlen as Cecily Cardew and Ncuti Gatwa as Algernon Moncrieff. Photo by Marc Brenner

Eliza Scanlen as Cecily Cardew and Ncuti Gatwa as Algernon Moncrieff. Photo by Marc BrennerSo we’re back to colour, and apart from casting – the stage and costumes do scream Bridgerton. But even here, we’re witnessing a triumph at play.

The Netflix smash is an adaptation of the Julia Quinn novels which would certainly have regaled hoards of thrill-seeking bookworms with “something sensational to read on the train”, and whose predecessors Wilde skews in this very play with references to the ‘three-volume novel’.

But it’s no bad thing to piggyback off a mainstream thing that’s done at least some good. And for all its overtures to ‘triviality’ – there is, once again, an electric currency to a production of The Importance of Being Earnest that is wildly, passionately, devotedly, hopelessly out and proud.

January 12, 2025

Nosferatu (2024) – Feeding with Friends

“It’s a real film, Jack.”

I keep thinking about this quote from Boogie Nights whenever I watch something that isn’t just fodder for streamers or yet another placeholder entry in a long-running series – be it film or TV – and which instead exists in its own moment and on its own terms, with a lived-in texture we’ve trained ourselves to be nostalgic about. The line is uttered from one pornographer to another, as they marvel – with misdirected smugness and surprise – at how a nominally more ambitious project of theirs appears to scale new heights of taste and credibility.

A similar feeling crossed my mind as I sat down to watch Robert Eggers’ much-anticipated remake of Nosferatu. You may be tempted to think that this is because I consider genre cinema in general and horror in particular to be inferior to other forms of cinematic expression, but anyone who knows me would laugh at the mere idea of me taking such a stance.

No, this is more about the way in which Nosferatu feels like a “real film” – more to the point, a tentpole blockbuster of yore – in the same way as George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road felt like a real film.

Something made with excess, and a sense of abandon and sensation (if not sensationalism) at concept stage. But which then proceeds with an evident care and love as it paints itself on the screen. Just because we’ve evolved to understand how film language works doesn’t mean we cannot thrill to witness it being made with the same tools that evoke the true effort behind the magic.

(Better writers than me have delved into the aesthetics and mechanics of how these auteurs do what they do, so I don’t really feel it’s necessary for me to delve into a granular analysis of just how they achieve that spark).

Audiences understand how a story gets from Point A to Point B, and sure – that should be good enough for you to follow the entry of the latest Star Wars or Marvel Cinematic Universe entry. But the engagement you get from those franchises has less to do with your immediate experience of the individual film or TV series in the now and more about how they can reward you with more entries in the future… and who knows? Maybe someday, one of those entries will give you the same thrill you used to get in the early thrill of Phase One, when you were young to its potential, when you believed you were actually experiencing an Event right there and then?

The irony of Nosferatu’s Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) identifying himself as little more than pure appetite, when in fact it’s Eggers’ film that likely to leave us pleasantly full, sated and satisfied, whereas its erstwhile competitors in the mainstream genre sphere peddle the wares of long-form addiction – an exercise of endless deferral that also speaks to something resembling a pyramid scheme.

Parasites, like the truest of vampires.

Here, have another franchise entry. Just sit through this one, and I promise the next one will be even better. I’ll throw in a couple of cameos for free – you recognise that obscure character in the post-credits sequence, don’t you? Good on you – don’t you enjoy that hit? Don’t you want more?

“It’s a real film, Jack,” is also an acknowledgement that maybe, now, these guys could be readying themselves to make something won’t just bump them into a bracket of respectability previously closed off to them; it could also result in the creation of something socially beneficial… a movie that could be enjoyed as a movie and not just masturbation-fodder to scratch a particular itch, an itch which remains because pornography – and individual franchise entries – exist to leave you craving more.

Of course, anyone who’s seen Boogie Nights will know that the line is poised as an ironic act of hubris. The ‘real movie’ in question is a ridiculous pastiche – what we see from the end product are mostly corny lines pitched purely for laughs. But strip away the trappings of 1970s porn industry that informs Paul Thomas Anderson’s film and you’ll find an earnest beating heart which speaks to the vulnerability of that moment of creation.

To this end, another comparison comes to mind – one that cleaves more closely to the six degrees of separation that lead us back to Eggers’ Nosferatu – is Tim Burton’s Ed Wood. Burton treats the ‘worst director of all time’ with the same compassion and empathy that Anderson reserves for the collection of lovable losers and chancers that populate Boogie Nights, and in doing so makes us feel deeply for someone attempting to make art on their own terms.

Luckily for all of us, Eggers is no Ed Wood. But if you’ll pardon a pun more gross and disgusting than anything you’ll see in Nosferatu (full-frontal Orlok included)… we miss the wood for the trees when the end result is all that we focus on.

Particularly when the well-oiled machine of the rival franchises is all about the result – slick and nicely packaged, but also endlessly deferred with the promise of future packages to come.

What is this if not the same animating force behind art generated purely by AI? And wouldn’t both Wood and Eggers – opposites on the spectrum of quality as they are – stand in direct opposition to such a homogenising machine?

***

Now, the texture that enriches the Nosferatu experience is also the kind of thing that would inspire addiction-adjacent rewatches, but I’d argue that this would be more of an act of communion, a revisitation akin to the healthy time spent with a good friend.

And I think this is what’s baked into Eggers’ process – the weirdly wholesome and probably somewhat anachronistic idea that ‘hard work pays off’; that not taking short cuts by doing all the nerdy occult/folklore research and having thousands of live rats on set will actually result in an appreciative response from the crowd you seek to court.

Of course none of these elements would work in isolation, and one of my own fallacies as a burgeoning artist was in fact the belief that churning ahead with the surface-level, craft-based elements will be what will allow me to eventually be taken seriously.

But when the mainstream morphs into an automated machine that can generate something resembling the shell of what you used to love, it is the humans in the mix who will remind you that what you love can still exist, across the same “oceans of time” that Gary Oldman waxed lyrical about in his own take on the vampire Count that served the basis for all the Orloks that followed.

August 13, 2024

a prayer to banish a prayer

I was molested on the bus when was around eleven or twelve. A squat man in a red shirt, specs and black hair approached me — we were both standing — and started to pinch and rub at my armpits and neck. Determined, focused on his task. He saw me and it was like he’d remembered to check that off his to-do list — like throwing in that last bit of leftover tomato into the garbage bag before closing it up and leaving it on the doorstep and then heading out, on to the next task.

He looked me straight in the eye. I waved him off, of course, I made my displeasure known. But he needed to do this and he got it done, and after a few more swats from me he moved forward — like a fly buzzing from one victim to another. (The term sex pest suddenly gains more currency in my mind).

We were standing because the bus was full as it always is on the Sliema-Valletta route in summer. The group of tourist girls seated by me may or may not have witnessed the whole thing, and they may or may not have turned to each other to laugh at what happened.

They were young, but not too young — maybe in their early 20s. One of them nudged their friend to attention in the row ahead and smiled, maybe pointing at me, maybe not. Maybe I’m assuming they were laughing at me because what happened to me kicked me off my center, and I expected a reaction from people and they happened to be the first people my gaze turned to, and I couldn’t imagine them to be indifferent so I imagined them to be cruel.

I never told anyone because that would mean that this had actually happened, that I had allowed it to happen and that this made me vulnerable to it possibly happening again. It would also mean that I was, perhaps, predisposed to this happening by something in my very make-up as a young person.

Not that I deserved it, exactly, but that I had somehow magnetically attracted this man towards me and let this happen because it was always meant to happen. Plus, the abuse was by all accounts negligible in terms of duration and measurable physical damage. Three rubs of three strategic points on my upper body, and over as soon as it began.

I return to the way he just materialised, as if he was put on this earth to do this one thing. No leering, no charming of equivocating. I was his for the taking and he needed to tick me off his list.

The heat and the crush of tourists, that old yellow bus bumping and rocking on the pothole-rich roads and jangling like a pocket of loose change in a fistfight. It’s so easy to get lost in these textures, some of which I’m even nostalgic for as the buses became more streamlined and less and less personalised — it’s the company that fully owns and runs them now, and the drivers aren’t assigned a vehicle each that they can decorate with that mixture of the sacred and the profane — a Madonna juxtaposed against a ‘glamour model’; Jesus side by side with Maradona on the dashboard — but are largely made up of interchangeable new arrivals brought in from other countries and rendered anonymous by the economic model which squeezes them into social irrelevance.

But back then, that day was just like any other summer day and it meant that the buses were an extension of the village festa: managed by burly men keen to keep things running as they always have, with tourists brought along for the (literal) ride to gawp in either genuine affection or creeping disgust at these ostentatious attempts at local charm.

Yes, there was a lot to be distracted by, on that day and many others since.

But what didn’t leave me was the sense that I was somehow built for it. I didn’t suffer a repeat of the same — no other man touched me without consent since — but I did come close. The man who sat close to me on the bus and tried to make conversation. The wiry frame, keen eyes. A manic energy that didn’t dissipate, even after he’s sat down next to me. Tanned, tanned enough to be on the prowl all day, I think. “Whoo, it’s hot, eh!” I didn’t respond. I didn’t even look at him. “German, German?” he asks. He get off a few stops later, and my panic-response unclenches just a little bit. Even if I know there’s tons of these men about and that some of them may be on that very bus.

It feels like it was the same guy who some time later — months or years, I’m not sure — stretched out his towel right next to mine when I went for a solo swim at Surfside. Back when tourist season wasn’t a year-long thing, and this was either early or late summer and it was off-peak hours. I struggled with debilitating anxiety and depression even at a young age, and I was proud to have carved out this little ritual for myself, and by myself. That I could use this to beat boredom and to get some exercise. My mother noted the positive effects it was having on me, and it was quite something to get that rare bit of unconditional validation from a woman who held herself to an impossible high standard, which of course trickled down to everyone else.

The man turned to me face me. I’m imagining him as tan, lanky and tall, donning black Speedos and flashing a smile of milky white teeth. He asked for the time, and I think I indulged him. I then packed up my things and left. I stopped going to the beach alone after that.

These men demanded access to the bodies that they wanted. They assumed that my body was a threshold they were entitled to breach, either by brute force or none-too-subtle pre-emptive coercion before going in for the kill. But perhaps I’m being overly cautious, even generous. Entitlement means that a threshold doesn’t exist, or that it doesn’t apply to them.

“Why me?”, feels like a pointless question of course, but if it is pointless then all of the above is too. In other words yes, talking about this won’t turn back time, it will allow for neither revenge nor justice. But these niggling feelings are why we write, and I am writing right now about this, for the first time ever.

I thought about “why me” a lot over the years. The surface-level and ego-rattling interpretation is that I probably looked vulnerable, a ‘soft touch’. I was a skinny blonde kid — indeed, mistaken for German — in a Siculo-Arab island state where hairy, olive-skinned burliness was the norm. A waif. A twig just aching to be snapped, with the same pleasure you would pop bubble wrap or step on a dry leaf.

Men will demand accessibility to the things which are weaker than them, but from which they can derive even a tiny measure of enjoyment. I learned to believe that I was well-placed to fulfil that function, and I carried it with me everywhere. In school at the hilariously male-prison-like Hamrun Liceo, and at work too, where I kept my head down and worked without complaint even as the newsroom sapped me of energy (and my weekends) for a crucial chunk of my adult professional life.

But of course, none of this was true. It was the sickening thought planted inside me by the abuse, which assails you and then leaves a darkly humming mantra; a song whose refrain you’re forced to recite as a prayer each day. Like a pimp, the prayer promises to protect you, and claims it is the only thing in the world that can fulfil that function, and that without it, you will be cast out into the wilderness, and you don’t want to do that, do you? Surely you can’t possibly think that you’ll make it out there on your own.

Of course I cannot articulate the words of the prayer. That’s how it wields its power over me. It’s wordless, but it demands the incantation. I have to somehow say it, but I cannot use words, because words are my pathway to agency. Articulating it would enable me to pierce it and render it as ridiculous.

But I’m learning to let go of perfection. I accept that I will not be able to put down the exact words of the prayer. There’s no reason why it would be spoken in English, or any other human language, for that matter.

So I’ll try.

The prayer would go something like this: “This happened to you because you are weak and vulnerable and it is your destiny to be susceptible to these kinds of actions. There are people in this world who do, and others to whom things are done to, and you are in the latter category and the sooner you accept that, the easier things will be. You will apply this to all spheres of life, and in keeping your head down you will notice that you are safe and that people will like you. Some will use you and a lot of them will take you for granted. But that is just the price you’ll have to pay, and it seems to be a fair trade-off to me. Now, thank me for this insight, and for giving you and organising principle that you can cultivate and cherish in this otherwise chaotic life.”

It feels right on my fingertips, this approximation. I can puncture its silly assumptions and sillier logic because I can see it laid out in front of me just so. No longer looming, now stiff and splayed, a patient etherized upon a table. Who could’ve thought literary criticism could banish demons?

May 4, 2024

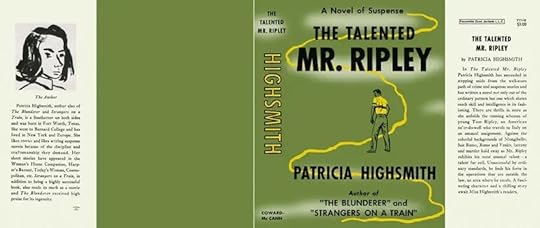

Tom Ripley Is An Author

I’ve just finished reading The Talented Mr Ripley for the first time and I can’t help but think of the story as being essentially about what it takes to carry a narrative to full term.

I remain convinced that Patricia Highsmith was essentially transferring the challenges of writing a novel onto a character who has no qualms about committing murder to further his hedonistic aims, but who is then also burdened with having to cover his tracks after the deeds have been done.

Like an author of fiction, he responds to creative prompts emerging from aspirational ideas of aesthetic fulfilment: here, compare the novelist’s desire to craft a masterpiece that recalls and respects their aloof influences and predecessors, with Ripley’s murderously driving urge to be in a position to soak in the fruits of high culture at his own leisurely pace, no matter the cost.

But what follows after you’ve responded to the initial call is the far more careful and laborious work of follow-through, where impulse must be supplemented with a quick-thinking application of intelligence, sensitivity and rigour.

I’ve never watched any of the Ripley film/TV adaptations — I was waiting to finish the book — but of course I was familiar with the overall premise by osmosis. What surprised me about Highsmith’s novel when I finally got down to it was how prone to emotional hissy fits Tom Ripley is, against the calculating, Hannibal Lecter-style sociopath that I had previously pictured. It’s like he does actually have the full range of human emotions at his disposal. He just parcels that energy out in a way that’s generally at odds with how you and I would manage it.

This aspect of the story speaks to how artists — we’ll consider writers as the main focus here — will tend to isolate themselves by proxy, at least while they’re cultivating and executed any given work. I’m not pushing the misunderstood outsider artist cliché here — I have good reason to be deeply sceptical of that cultural trope — but it’s true that a certain degree of observational distance is necessary for an artist to really focus and get stuck into the work.

And for writers, in particular, this can take on the tenor of detached people-watching. You’re putting characters in your story, and character are proxy humans that need to feel more human than human for the reader: the reader will, in fact, be compelled to become one and the same with them for the book to really live up to the full potential of the phenomenon of fictional narrative… in exactly the same way that Ripley assumes and then subsumes Dickie Greenleaf’s entire persona (an act of cannibalism so insidious it may even make the aforementioned Mr Lecter blush).

Which means that while the people you’re watching go about their routines, your own will be thrown off-piste for a bit, and you’ll be venting either through the characters you’re puppeteering, or in oblique ways and habits that will register as strange to the outsider.

But much like Tom Ripley’s own ‘bliss of evil’, there is something to be said about the plan finally coming together. Putting Tom’s shocking callousness to one side — which you will as you’re reading anyway, because Highsmith is a master at all of the above — the pleasure of the novel comes with watching with morbid fascination at how our man not only covers up the bodies, but spins a story that convinces everyone: from an international array of law enforcement officials down to the victims’ nearest and dearest.

Like any writer worth their salt, Ripley knows what makes his cast of character tick, and he knows when to tug at their strings and when to release. The most naked display of this allegory comes to the fore not through Ripley the murderer but Ripley the letter-writer. That’s when his cunning and skill at manipulation reveals the author’s brain at work.

The pen is mightier than the sword, indeed: or rather, it can serve as the civilised supplement to the sword’s blunt-force damage; bringing out of the animal realm of the murderous impulse and back to the showered, shaven and fragrant world of the cocktail-sipping chattering classes.

Of course, no novel is perfect, and neither is Ripley’s plan. Rerouting and improvisation is often necessary, and the utter unravelling of this delicate tapestry is never not on the table.

Consequently, another constant is the intermittent reappearance of blind panic: that demonic pulse at the core of us all — writers included — which beats out a tattoo that says ‘why did you even attempt this? It’s built to fall apart, and you know it’.

The fact that Ripley gets away with it means that Highsmith has given us a perennial cheerleader for our projects. If you’ve looking for a pep talk to motivate you while you plough through your drafts but (rightly) have no truck with superficial slogans and toxic positivity, the talented (and hardworking) Tom Ripley might just be your man.

April 28, 2024

Oh, you couldn’t dam that river

Some months have passed since my dad died and it’ll surprise no-one that I’m still processing everything that happened and that in many ways, the full realisation of the loss hasn’t hit me yet, and likely never will.

I’m also envious of those who could find it in them to mourn in seemingly more direct ways – bursting into tears as soon as they heard the news, or crying at any mention of him after the fact.

There’s a lot to be said about your brain working hard to “protect” you from being hit by the news that the person you’ve known since birth – someone who’s played a fundamental part of your life for 38 years – is now no more.

They are literally nowhere to be found in the living, material realm. You cannot hear them, smell them, touch them and certainly no longer hug them hello or goodbye. You cannot gossip with them, you cannot chastise them and you cannot show them affection nor expect any in return. You cannot visit them just to spend time with them – not even a wordless visit during which they click away at their computer and yawn between puffs of ultimately lethal cigarettes.

But this isn’t the worst of it, because this is all, still, the present – or at least, the very recent past. This is how I remember my father moving (sluggishly as it may be) and operating in the final years of his life. No, the torrential waters that the brain’s dam is desperate to keep at bay are the waters of layered history. Because my father was many things to many people, but to me he was dad, and that’s a multitude which contains many other multitudes within it.

A similar realisation hit me after my mum suffered a stroke which would plunge her into a coma that lasted a decade. A person is precious because they are a universe. A parent, in particular, exists as a storied shelf of memories and interconnected thoughts and behaviours; ones which continue to evolve and reverberate from each other while the person is still alive, but which are then frozen and ossified by proxy after they’re removed from the realm of the living.

This is where they can become mythologised if we’re so inclined. To some of us, or in some of our moods, this is also a site where it becomes easy to cast judgement with an illusion of rigid finality. You can draw definitive conclusions and cast a final verdict, now that the accused – or the lauded – is no longer around to contradict you.

In my father’s case, it is also about the extolling and fetishisation of an artist’s way of life. It’s so tempting to view the motor of this work as something which emerges from outside the common fold and which we can simply gawp at like it’s an alien diamond put on display just for us. As if the material conditions matter not a jot. As if he was given a gift and simply executed it with generous grace – bestowing his lessons onto others too, so that they may take some of the diamond for themselves.

It’s this abdication of the possible and the practical which allows many people to live in a similar phantasmagorical plane that my father occupied in the latter years of his life.

In any contemporary society dictated by the norms of neoliberal capitalism, living “free” means living at the expense of others – or of your own wellbeing and stability. It’s kill or be killed, eat or be eaten, and when you’re not eating others, well… then you just have to eat yourself. My father chose to bite the bullet of precarity and to swerve out of the neoliberal order instead of meeting it halfway. He spent his time making beautiful work which my siblings and I will now endeavour to protect and preserve. A sizable effort which will also require us to undertake an additional – and equally onerous – side-quest: finding help which is truly trustworthy in an island beset by mercantile souls in search of their next host.

I am also dreading each passing day, because I suspect that the worms will come out of the woodwork good and proper once they decide the grace period has passed and they are within their rights to come knocking at our door demanding the pieces of my father he often gave all too freely when he was around.

Because the phantasmagorical state means that people are not only free to romanticise him, but in that romanticisation – a swerve away from reality and into the same cloudy realm in which he’d made his home – they can reassess and re-engineer their own relationship to him like a piece of Lego. If all is true, everything is permitted.

So we had a situation where people that I know for a fact meant to do my father both reputational and financial harm in the recent past, had no qualms about showing up to his memorial and even posting and boasting about it on social media – lest the FOMO get too much and they be excluded from the collective chant they’ve been called to participate in… a blitz in which genuine tributes collided directly with vainglorious, self-serving bandwagon-jumping.

Being an artist means that you’re public property to a certain extent, and my father’s accommodating nature meant that everyone had their own piece of his memory to take home with them. But it’s a piece free from the vicissitudes of the raging torrent that the dam is just about keeping steady for me.

Crucially, it’s a piece that may be small but it illuminates quite a bit, blessing the keeper with a selective blindness. So we would be forced to parse through DMs from apparently well-meaning Senders but whose content was so blisteringly insensitive it was difficult to even believe a human being took the time to type them out and hit ‘Send’. Like the Sender who, for example, implied that they should be the ones to archive my father’s work as they suspected that the family would be tempted to just leave it to rot somewhere.

In this instance, the family becomes secondary – lumpen byproducts of the artist’s creative process, clearly ill-equipped to handle his legacy because they weren’t seen to be going through the usual motions that fellow darkroom acolytes went through, and posted incessantly about on their socials.

In a lot of ways, this is a crucial consideration because it cuts to a deeper vein of my father’s life, work and his appeal to many.

It is down to that hopelessly fraught term: authenticity.

Many have extolled his sincerity, generosity and his apparent lack of ego, at least when it came to executing and promoting (or failing to promote) his work. The problem is that authenticity is entirely inimical to the status quo we’ve already mentioned. This is why my father’s version of authenticity was refreshing – it projected an alternative way of being which some sought to emulate, others to exploit.

Never mind that all the features which people were quick to romanticise about my father, came to the fore only a decade or so before his passing. He dove back into photography in earnest after my mother’s stroke. Always in search of low-hanging-fruit solutions to make some money while still catering to his creative instincts, he started giving workshops to an eager gaggle of hipsters (yes, the term still had currency back then), and it was from there that the whole Zvez vibe became a thing; that darkroom and oak table occupying an iconic space in the memory for many, hipsters and not.

But, faced with the imminent need to vacate his apartment, I was also faced with old family photos. They command more attention from me than his subsequent, lauded works. They are the propulsive energy of the waters beating against the dam. They tell of a life lived – of a struggling immigrant family, and of a man still plugged into the churn of day-to-day life. Put-upon and frustrated, sure, but certainly not relegated to a cave of his own making, gawped at by those with a hole to fill, the crowd that real friends with real love have to machete through for a glimpse of my father’s attention.

They deserve space and time, and that’s why I’ll end it here from now because there are no neat endings in this process, only hard-won new beginnings.

***

Photography by Virginia Monteforte

December 28, 2023

Zvezdan Reljić (1961-2023)

My father, Zvezdan Reljić, passed away on 22 December 2023 after suffering a massive heart attack a few days prior. He was 62.

A photographer and print-maker, he leaves behind a legacy of work that has attracted a myriad of admirers at different stages of the process. Because it wasn’t just the end product that drew a crowd. Through his film photography workshops, he slowly amassed a myriad of students who found in him an accommodating tutor, teaching them the ropes as he reignited his own passion for a vocation he had to put the wayside as he raised kids and kept a family afloat after emigrating all of us from Serbia to Malta in the early ’90s.

The black-on-white CV version of his life will tell you that his most notable works include the book Wiċċna / Our Face (2018) — a collection of portraits depicting the polychromatic reality of cosmopolitan Malta, gathering faces of those who were either born, settled or simply passed through this ancient but ever-transient island in the middle of the Mediterranean which our family made into a home, finally becoming fully naturalised citizens in 2012.

The CV would also then include a reference to his most recent achievement: the solo exhibition JA! JA! JA! at R Gallery in Sliema, the town in which he was still living at the time of his death, in the rented apartment of 3A, Panorama Flats, into which our family settled after a nomadic couple of years and for which I wrote this poem on the occasion of the exhibition’s finissage.

The CV would then also list his publishing venture Ede Books, responsible for some award-winning titles and latterly, the publication of hand-printed & pressed chapbooks: yet another manifestation of his DIY approach, coupled with his desire to discover and elevate fresh voices in the community, while also giving the more established players a welcome breathing room to experiment on the fringes.

The CV, and the established bio, would also necessarily have to mention that he served as president of the Kixott Cooperative; a small but vibrant cultural hub in the town of Mosta, which arose in 2019 as an endeavour by “my family and other animals” and went through various permutations and faced numerous challenges — the pandemic, in retrospect, being the least among them — but which survives as an events space, bar and small bookshop that consolidated the communal space which my father opened up to students and other artsy aspirants, after my siblings and I flew the coop, which we gradually did following my mother’s stroke and extended “exile” in a care home.

Many beautiful tributes have already been penned and some — such as this one by Seb Tanti Burlo and this one by Chris De Souza Jensen — have even been drawn. Our long-standing friend and colleague Matthew Vella wrote a beautiful obituary for MaltaToday, where both my father and myself worked for a long period of time, establishing both of our careers in the process. The piece is as impassioned as it is comprehensive, and collates the life and career in a way that only a seasoned journalist who is also a dear friend can manage.

Many will talk about how my father helped galvanise an artistic community, and that he offered a ‘safe haven’ for rootless yet artistically ambitious souls: both at Kixott and in his own home. It’s a beautiful image and memory to cling onto.

But of course, every romantic impression comes with the flip-side of harsh reality. And as his eldest son, along with the rest of the family, navigating my father’s legacy will be about accepting the challenges that some with the ‘public vs private’ aspects of it all… which were further complicated by his opening up his doors to so many people.

Going forward, there will be a lot to unpack. We need to ensure that his work survives, and is sheparded to the right places as carried by the right hands. (Being as accommodating as my father was meant that a few bad apples will, inevitably, slip through the net.)

But that’s yet to come. The smoke is still clearing. And after the tributes gradually recede, the silence will be deafening and the true work of grief will begin.

December 17, 2023

Book Review: A Death in Malta by Paul Caruana Galizia

My book review of Paul Caruana Galizia’s A Death in Malta: An Assassination and a Family’s Quest for Justice is now up over at The Markaz Review.

I was honoured to be commissioned to write the piece for such a prestigious publication, thanks to poaching by one of its editors, the Malta-based Rayyan al-Shawaf. I tackled it with some abandon (the original draft was far longer and far more winding), because the book itself is a heady hybrid that cuts to the bone while also providing the necessary context for an international audience.

The politics and ‘true-crime’ angle are very much in there, and will appease the readership looking for the necessary does of robust, hard-nosed investigative journalism that the Caruana Galizia family as whole is now renowned for.

But it’s the ostensibly ‘digressive’ passages that really struck a chord with this reviewer… one who’s had to internalise the Maltese context the hard way, and one who’s also lost their mother at a young age.

There’s a tendency among us Maltese to have to ‘explain’ what Malta is to the rest of the world. Usually this is done with pre-packaged touristy pride: the brochure version of the island’s greatest hits. But the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia led to a dark inversion of that habit, and this book by her youngest son offers the starting point of an in-depth exploration of what such an inversion implies.

October 19, 2023

Keep your feasts and keep your famine

There’s something surreal about still being able to glut on a banquet of streaming material as the Hollywood strikes rage on in the background.

Add to that the ‘feast or famine’ vibe of my own personal summer vs autumn streaming experience: there was very little new stuff I wanted to watch over the summer, and then October came along and I’m once again spoilt for choice.

Not that this is a new mood for me. For all the economic chaos we’ve been labouring under in the Western world since 2007 or so, that doesn’t really seem to apply to cultural consumption. Audio-visual “content” is piped in at a regular pace through our obedient army* of trusted apps.

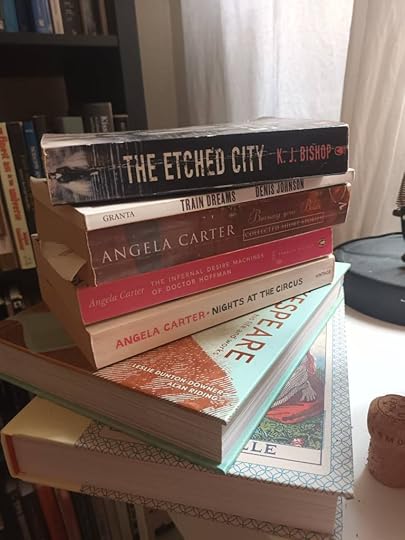

The “TBR” pile only grows and grows, and in my case, twists and morphs into Cronenbergian variants as I give up on one pile to forge another, confident in my prediction that this time, this will be the one that gets devoured.

Ready for them re-reads

Ready for them re-reads

This all stands in marked contrast to how I remember experiencing culture in the ’90s. As a geeky son of emigres who lived in Malta and spent summers back in native Serbia, but who was trained to desire the globalised products of the Anglophone sphere, I was often left blue-balled by my inability to grasp at all the stuff I wanted — nay needed — and required to consume. Consume, of course, on the basis of an imagined diet whose prescription was as vague as it was specific.

Getting comics in Malta was nigh impossible at the time, though there was a grassroots ‘comics club’ established by a pair of passionate — though often frustrated — friends who often treated its members as foundlings… which, in many ways, we were: orphaned in our need to latch onto story-products which would not otherwise have reached us were it not for their benediction.

The lack of a foundational cultural identity — or rather, a fragmented one that I wasn’t particularly keen to embrace or even poke at, given that Serbians were officially the aggressors in the nineties’ most significant conflict, rudely blotting the End of History with its own traumatic fallout — is perhaps what led me to latch onto various subcultures: comics were one, metal music was another.

Funnily enough, our trips to Serbia were particularly useful when it came to the latter. The mess of the post-Milosevic era meant that bootlegs could proliferate with impunity — public television channels even aired brand new cinema releases on their evening schedule — so we’d end up taking a bunch of CDs home and gain some degree of bragging rights with out metal head buddies.

Because for all that it was still struggling under the weight of a post-war depression, Belgrade in particular remained a European cities, and subcultures still functioned with an historic sense of purpose, and kindred spirits could be found if you knew where to look. Malta, for all its aspirations of being an up-and-coming place, still operated on a provincial logic.

This was also why the rapid rise and fall of Napster — whose fall was made largely redundant by the floodgates opening up to handily-available variants — was a balm to us in Malta. Suddenly, we could all be on the same page as our international counterparts. Metal Hammer and Kerrang were no longer dispatches from the future.

And yet, fast-forward to the present day, and what I look forward to most re-read season. This is how I’ve unofficially dubbed autumn, over and above its many reliefs and delights (ostensibly cooler weather at some point — climate change permitting — the excuse to binge on horror faves ‘cos Halloween, etc etc.).

It’s about acknowledging a split. On the one hand, there’s so much desirable stuff to consume. On the other, all of that noise is just so piercingly alienating. And caring for the self is all about remembering what makes you, you. The foundations built by all those things that left an impact, for some reason.

This runs counter to the prevailing cultural narrative, of course, which is probably why I always feel an internal pushback whenever I try to implement it. But the relief of re-reading a favourite book is immediate, and immense. It’s a relief akin to the best of drug-free hedonistic pursuits: sex, swimming and a volcanic eruption of laughter during a friends catch-up.

Consumption is what sold us the end of history. But we were nowhere near the end, of course. And regardless, there’s always been a ton of history to feast on in the meantime.

*though a master-slave dialectic may be the more appropriate metaphor here.

October 14, 2023

Mibdul reviewed… in German!

Our plucky comic book that could — MIBDUL — gets the Teutonic treatment over at Timo Berger (@comic.timo)’s review page on Instagram!

There’s something about this far-flung little book being discovered in equally spontaneous ways that warms the heart. Check out the original post here. (Non-German speakers like myself can avail themselves of Insta’s admittedly efficient automatic translator).

Timo joins the Serbian online publication Strip Blog in giving Mibdul its due. Be sure to read the first and second of an ongoing review series that is thorough and incisively written, courtesy of Strip Blog’s in-house reviewer Ivan Veljković.

MIBDUL ships internationally via the Merlin Publishers website. Inez, Chris, Emmanuel, Faye and myself — that is, the small-but-fierce team behind this six-issue mini-series — would be most delighted to hear what you think of it.

Indie comics thrive on word-of-mouth, and as a particularly ambitious project in that vein — stemming as it does from tiny Malta, engineered and engined with a pioneering streak — Mibdul is as indie as they come.

September 2, 2023

Poem: 3A, Panorama Flats

Poem read on the occasion of the ‘finissage’ event for JA! JA! JA! — an exhibition of print works, photography and installations by Zvezdan Reljic at R Gallery, Sliema.

Zvezdan Reljic is my father, and 3A, Panorama Flats is where our family was based for a number of years, and whose sofa featured as a prop in the exhibition.

***

3A, Panorama Flats

The place is an afternoon.

My room is a terracotta cocoon.

Etruscan. The texture of clay. Amphorae retreived from the bottom of the sea.

We had a view of the same sea, once.

The view that gave the place its name, I guess.

The panorama thinning out over the years to make way for more apartments.

But I allowed myself to think, none of the new apartments are like ours.

I allowed myself to think: this is ours, and ours alone.

I allowed myself to think, the cocoon will be there for me.

QUOTE, this place is huge. You guys are so lucky UNQUOTE.

QUOTE, they don’t make them like this anymore, UNQUOTE.

The place is an afternoon.

The light lands on the corridor in a strong thin strip.

Falls on the rusty back terrace. On the vintage furniture. The vintage furniture whose cousins we spotted in the wild once, at an exhibition commemorating Maltese modernist interiors.

The light stops at the doors. Our doors. We each have a room.

QUOTE, We’re not like your typical family, really. We’re more like flatmates. UNQUOTE.

The place is an afternoon.

In the morning we disperse like rats. Into our rooms, or out of the place.

And at night, others seep in.

At night, the new people gather around the oaken table.

QUOTE, My friends after midnight. UNQUOTE

But the place is an afternoon, because then I’d sneak into my mother’s studio while she made dresses and sit on the sofa and talk about nothing.

Now it’s a darkroom, and the time of day no longer matters.

QUOTE, We’ll talk later. I have people coming over, UNQUOTE.

The place is an afternoon, but there’s no longer a cocoon for me.

The Etruscan room is whitewashed. Colonised and recolonised. But clean. Finally clean. We’re roommates, all of us roommates.

The place is an afternoon. But if you sit on the sofa while you sip on a Turkish coffee you’ve been drinking far too late in the day, you can see the evening make its way in. This how you can start to say goodbye.

But it’s a process. You’ll need an instruction manual. But you won’t find it heaped among the books, papers and discarded prints. You’ll need to write it by yourself.

So this is me trying. Here goes.

Close the room that once made dresses and that now makes images.

Close the room to the corridor.

You’ve allowed the place to become a box.

The hard twilight hits the oaken table. And you realise, for the first time, that it’s not rough at all but that it gleams smooth, with a surprising freshness.

You sit on the sofa. You sip that umpteenth Turkish coffee.

The light sits on the neighbouring buildings until there’s no longer any of it.

The place is no longer an afternoon, but the coffee won’t let you sleep.

Get up, get out.

It’s time to start walking.