Teodor Reljic's Blog, page 3

August 27, 2023

Words will wait

Writing hasn’t been easy lately.

That’s not to say I haven’t been able to jot things down. And neither am I “out of ideas” or bereft of the required energy or confidence to keep on ploughing through the sentences and drafts.

It’s just that my current project is at a point where the drafts, the ideas and the characters need some time to get to know each other better. They’re talking at cross-purposes and on a vague, sun-bleached plan, which was mapped out by a remote authority seated in a comfy office and simply left out to the elements and the drafts, the ideas and the characters are forced to squint to make out the shapes which were once words or diagrams meant to take them to the next stage of their journey.

This probably just means that I need to take a break.

Which is funny to consider, when my writing schedule is essentially “whatever you manage in the one hour before you have to head out to go to work”. But a mental break from a specific strand from writing doesn’t necessarily mean stopping to write altogether. Even switching projects works, though arguably swapping over an ingrained, long-term writing practice for some experimental noodling could have an even greater restive (or restorative) effect.

***

Freedom in writing is always a relative term, for me… I’m deeply sceptical of the idea that an artistic practice implies a sense of spontaneous, intuitive and even anarchic liberation away from the strictures of mainstream society. If anything, I find that it actually requires a deeper and more neurotic commitment to some of these tenets, with the anarchism only made evident in the obsessive streak with which you double-down on them.

You can zone out at work, and go for the umpteenth cigarette or coffee. Household chores have definitive parameters, and even the most byzantine of bureaucratic tasks have some kind of ceiling. Clients will have deadlines, and even lovers have their ultimatums. Lovers, partners and friends also have physical bodies that tick away to sometimes endless-seeming, but ultimately finite desires and frustrations. They may be erratic but they’re never truly, entirely unpredictable for those of us who know a thing or two about how humans operate in general. And while they may expect a certain degree of telepathy on your end — and as annoying as such an expectation may be — they will never ask you to create and recreate them anew.

But your characters will. And this is why I think that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein will always remain a reference point. I’m sure there’s a flurry of doctoral theses and obscure articles out there to prove the following statement wrong, but I’m always surprised that so much of our processing of that pioneering piece of sci-fi gothic literature is focused on the ‘scientific hubris’ reading, and so little on how it’s also a commentary on the act of creation. Yes, I’m sure the theological implications have often been made as well, but I’m referring specifically to how Victor Frankenstein could also be seen as the neurotic and nervous artist trying to come to terms with the horror of a first draft. (And also, how that first draft threatens to morph into something unexpected, and demands that more of these mutations be facilitated by dint of a fertile co-partner).

(I’m not trying to claim this interpretation as original. Those of you have links and PDFs, please pass them on. They are more than welcome).

So yeah, for me, writing is never about freedom but about finding the right straitjacket for the right moment. Or rather, the correct protective suit for whichever uncharted territory you happen to be traversing at the time. Because the territory will always BE uncharted, and populated by monsters to whom you’d not only have to teach language, but whose independence you’d have to facilitate and reassure. Let Victor Frankenstein’s fate be a cautionary tale.

***

Apart from being literally one of two or three annual events I legitimately look forward to each year, the Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival, organised by Inizjamed, often offers me a chance to experience writing in a looser and more immediate way to my default mode. More poetry, less novels. More of experimental prose, and less of the three-act structure.

It often results in me buzzing with a renewed fervour for the written word, experiencing precisely the kind of ‘break-that-is-not-a-break’ that I’d mentioned earlier. You encounter new writers without the aid of an algorithm: better still, right in the flesh. This adds wrinkles to your programme; unexpected experiences that open new doorways.

But there was a dash of welcome familiarity in this year’s edition of the festival. As an honorary member of the extender Inizjamed family, I’d assumed that I had some dibs on suggesting future festival guests. So a couple of years ago I started lobbying for the inclusion of Karin Tidbeck to the roster. Of course, as a subculture-rat since my early teens, my allegiance to specific groups will always trump pretty much all else: in this case, it’s the genre/speculative fiction community. I will always aim to advocate and represent of that literary class in my local stomping grounds, much in the same way I managed to do for Kali Wallace and Jon Courtenay Grimwood.

But I also felt Karin to be germane to Inizjamed’s festival in particular for more specific reasons related to their artistic practice and MO. A festival that comes with its own translation workshop attached, a multi-lingual, self-translating author is practically catnip. And a writer who so keenly identifies with liminal spaces can’t help but feel at home in any festival that deigns to include ‘Mediterranean’ in its title, and this particular one does so with a degree of conviction: operating with both intellectual rigour and humane generosity to create authentic spaces of encounter.

***

All of this largely a preamble to celebrate this year’s edition of the festival (as I did when I was lucky enough to participate back in 2018); to remind you that I got a chance to chat with Karin in print about their uncategorisable nature in the run up to the event; to brag about being allowed to ventriloquise for Karin in her absence from the grand finale due to a ridiculously early wake-up call the following morning; and to hopefully open this space back up for more regular, and looser, writings of this kind.

Especially now that I’m starting a new job in a field that’s relevant to my experience once again. Which is the perfect push and pull of the familiar and the new.

***

I mentioned the prolific (and gentlemanly) Jon Courtenay Grimwood above. During one of our in-person conversations (either during his Malta visit or a follow-up meeting in London, I can’t recall), I spoke admiringly of his substantial output, a lot of it filtered through different noms de plume.

He responded by stating simply, “Well, if I don’t write, I can’t think.”

Increasingly, I find this to be true in my case. It doesn’t necessarily mean that whatever I write will have any value at all; at least not in that early stage. And neither does it have to be some sort of revelatory, epiphanic distillation of the self at that given moment.

The mechanics of writing are their own reward. This is why every single shift away from the programme has value. Words remain words. They will serve you in different ways at different times, but they remain at your disposal.

Featured image: Authors performing at the final night of the 18th edition of the Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival, on 26 August 2023. From left: Tanja Bakic, Claudia Gauci, Karin Tidbeck, Simone Inguanez and Virginia Monteforte (photographer)

May 5, 2023

Streaming through a strike | Beef, Dead Ringers, The Bear

The things you take for granted.

Like the vast slew of hard-hitting, boundary-pushing streaming TV shows that manage to both hook you along for an escapist journey that also makes you think of the world you’re living in, RIGHT NOW, for all that you live on a tiny speck of island in the middle of the Mediterranean and said shows would be conceived and shot oceans away.

(Though the latter may not always be true — some would be filmed closer to home, in jurisdictions with comparatively weaker film unions, but that’s a story for another day. Or is it?)

Shows like Beef, Dead Ringers and The Bear: a powerful but eclectic bunch (I know I’m late on the last one) and an example of the kind of stuff we’ve learned to yes, take as a god(s)-given gift without questioning its provenance.

But the currently-ongoing writers’ strike puts what we take for granted into real perspective.

Funny Feud: Steven Yeun and Ali Wong in Beef (Netflix)

Funny Feud: Steven Yeun and Ali Wong in Beef (Netflix)When I posted to my socials about how much I was enjoying BOTH Beef and Dead Ringers, the enthusiasm came thick and fast for the former: a zippy-snappy comedy-drama forged by the joint behemoths of Netflix and A24; a charged melange of commercially friendly adrenaline-hit episodes and an arthouse-boosted satirical, observational backbone (that one of its two main leads is a professional stand-up comedian by day surely helped channel some that energy).

But few seemed to be aware of Dead Ringers, despite its starring the quasi-generation hopping, quasi-household name of Rachel Weisz (multiplied by two, no less). Here’s a show that seems to be playing all its cards right: like FX’s Fargo, it is a legacy reboot of a cult classic film — in this case, David Cronenberg’s 1988 surgical fever dream opera, conducted by Jeremy Irons times-two — and, again, it stars an actress we’ve had a chance to fall in love with over and over again in projects which range from award-baiting costume dramas to prestige espionage thrillers and endlessly rewatchable action-adventure capers. And this is hardly about Weisz taking a swing to give a newbie a chance: the show is penned by Alice Birch, a regular scribe for a little show by the name of Succession.

Double Trouble: Rachel Weisz in Dead Ringers (Amazon Prime)

Double Trouble: Rachel Weisz in Dead Ringers (Amazon Prime)But just like Variety‘s article on the matter states, the gold rush for shows has led to a saturation point that’s created an absurd scenario, where even projects with the marquee-est of marquee actors struggle to find elbow room in this crowded space: “Do you remember the Julia Roberts series on Starz last year? What was it called? How about Samuel L. Jackson’s series on Apple TV+? And they were good shows.”

Dead Ringers is also a good show. Not as easy to watch as Beef, certainly — for all the moral wincing Beef pinches at, DR squeezes the corkscrew in far deeper while cackling at your pain — but to me, at least, it brought back memories of another favourite yet hard-done-by programme: NBC’s (or should we say most emphatically above all, Bryan Fuller’s) Hannibal, once again starring a couple of Hollywood primed behemoth thespians in roles of a lifetime.

Both DR and Hannibal are pointedly indulgent programmes, more in terms of tasteful production design than anything requiring a surfeit of digital effects (though I’m sure its painterly bouts of bodily violence did require some tinkering in that regard). It’s the kind of stuff that gets made when both literal and figurative stars are aligned.

Love Crimes: Mads Mikkelsen and Hugh Dancy in Hannibal (NBC)

Love Crimes: Mads Mikkelsen and Hugh Dancy in Hannibal (NBC)But they’re also the shows that risk getting buried under the avalanche of material that the streamers have insisted on churning out to appease the gods of growth. A malaise that has infiltrated many areas of our life, for sure, but that’s how it’s manifesting itself here, among the very shows that we settle down to watch after our own daily reckoning with what’s asked of us by late capitalism.

It may not be as baroquely pretty as DR or Hannibal, and neither does it attempt to chase the zeitgeist like Beef, but The Bear — whose characters traffic in literal beef! — may serve as the best compounded allegory for this mess.

Just like we tend to forget about the writers who toil away to conceive of the avalanche of shows we not only take for granted, but that we are actually spoilt for choice over, so would a (largely off-screen) clientele fail to consider the full extent of the sacrifices made by the chefs delivering up signature beef sandwiches in The Bear.

Pressure Cooker: Jeremy Allen White in The Bear (FX)

Pressure Cooker: Jeremy Allen White in The Bear (FX)It’s not so much about stoking a dormant guilt in us. That would defeat the purpose, and even be counter-productive. It’s also not about some passive idea of ‘awareness’; of simply paying tribute and showing appreciation and then flipping back into default mode a second or two later.

But it may be about remembering that we watch these shows primarily because they explore the things that make us people… as stylistically exaggerated and/or excessively zoomed-in as they may be. And if the people making them are sidelined — either through dismal pay conditions or by defaulting to AI solutions — well, that deflates the whole point of watching these shows in the first place, don’t you think?

December 25, 2022

Annual Batman Returns Christmas Rewatch: Stray Observations

A kiss can be deadly if you mean it.

– My favourite movie Batmen — Burton here and Reeves’ recent outing — are the ones that display at least a glancing affinity with subcultural figures, in contrast to hectoring enforcers of the status quo. Musical choices confirm it.

– Case in point: The Batman (2022), famously, re-introduces Nirvana to Gen Z, and on top of ‘Returns’ pan-freakshow of fetishistic weirdness, let’s not forget that Bruce and Selina kiss under the mistletoe while Siouxsie and the Banshees are snuck into the playlist for the Gotham one-percenter’s schmoozy Christmas do.

– The very ’90s ‘battle of the sexes’ sub-theme just scans as quaintly adorable now.

– Yes, Burton was unfettered this time around in contrast to the 1989 original. But I dream of a world where screenwriter Daniel Waters was ALSO allowed to go full Heathers on this one. Not that I don’t cherish the crystalline nuggets of punny dialogue that do betray his indelible presence. And on that note, last but not least…

– Max Shrek absolutely, positively, has the best lines.

POSTSCRIPT: It’s hardly surprising that a beloved film you love so much and have rewatched so often leaves an indelible stamp on both sub- and conscious mind. And over the past couple of rewatches, it’s become clear to me how strong an influence this movie in particular has been in the creation of Mibdul.

November 28, 2022

In Defense of Escapism

Following the annual horror binge of October, I tend to slip back into fantasy favourites during the subsequent months in an attempt to close off the year with something of a cosily immersive lilt; to both weather and take advantage for what passes for autumn and winter in this warm part of the world, and to plug into its wellspring of restorative nostalgia.

This often gets me thinking about the vilification of the fantasy genre — broadly speaking — as ‘escapist’, which tag tends to be loaded and, as is often the case, flung around in a dismissive and rather unreconstructed way.

The implication being that, the further we are from a cleanly mimetic representation of reality in fiction, the more ‘irresponsible’ we become in its consumption. That such a mode encourages us to forget the world as it is now, in favour of an ethereal indulgence that numbs us to our day-to-day realities and leaves us in a torpid stupor, the kind that Tennyson detailed in The Lotos-eaters.

There’s of course been endless shadings and nuancing of this argument over the years, but I believe that the core of it has remained with us — throbbing like a planetary core that has lodged itself and become essential to historical ecosytem of the discourse, much like any other ossified truism.

The Rings of Power (Amazon)

The Rings of Power (Amazon)

I find it to be endlessly faulty, and not just because I’m a fan of fantasy literature (and therefore don’t appreciate being characterised as some sort of head-in-the-sand naive idiot by proxy).

My issue here is far more fundamental. To put it as plainly as I can manage: it assumes that reality is a flat, clearly definable surface, and that we can posit a clean reality : fantasy binary.

The popularity of such an assumption is hardly surprising, given that it’s taken root primarily within the confines of a materialist, capitalist western society. This is a mode of living which at best compartmentalises all that is not tangibly measurable, rendering it peripheral to the day-to-day workings which make the machinery tick.

So that religious practice is tolerated, as long as it can be woven into the fabric of the day-to-day without causing too much offence (and crucially, it is called upon to occasionally prop up the agendas of certain politicians and ratify certain acts of exclusion and social inequality).

Acceptable escapism? Naked Lunch (1991) by David Cronenberg, adapted from the William S. Burroughs novel

Acceptable escapism? Naked Lunch (1991) by David Cronenberg, adapted from the William S. Burroughs novel

Perhaps we accept the intangible when it relates to issues of mental health. There is, at the very least, an understanding that — medication-based psychiatric help aside — the mental realm needs tending to in ways that are suspiciously apposite to the kind of treatments and rituals we would associate with religious and/or magical practice.

But even then — the overarching practise is to simply ‘treat’ any mental health anguish in a way that’ll make it go away so that you can resume being a healthy cog that can help keep the system chugging along. We are hardly encouraged to take its wider implications — that there’s more to life than what’s in front of us — and run with it.

In the same way, fantasy is also compartmentalised, only to be richly consumed by all of us. Literature aside, its popular adaptations litter our screens and the streaming services that have latched onto them like eager barnacles. Adaptations of the works of JRR Tolkien, George RR Martin and Neil Gaiman were some of the most-watched (or at least most talked about) shows of the past year or so.

Chloë Grace Moretz in The Peripheral (Amazon)

Chloë Grace Moretz in The Peripheral (Amazon)

Even something like Amazon’s take on William Gibson’s The Peripheral — ostensibly a work of ‘hard’ neo-cyberpunk from the grandfather of that subgenre — ultimately partakes of fantasy tropes at its root: it’s a portal fantasy with virtual reality and cyborg stand-ins only superficially replacing the mechanics of magic and its adepts.

Ultimately, branding fantasy more escapist than its supposedly ‘realistic’ counterparts is bound to devolve into a fool’s errand animated into being solely by the assumptions of a category error.

Still from The Company of Wolves (1984), directed by Neil Jordan and adapted from the Angela Carter short story

Still from The Company of Wolves (1984), directed by Neil Jordan and adapted from the Angela Carter short story

If you’re reading, watching or hearing something — anything — for an extended period of time, you’re lost in that experience, and at least somewhat disconnected from the real world, by proxy. Whether this is an epic adventure quest populated by dragons, elves and goblins, or a kitchen-sink drama of an immigrant family trying to make ends meet in present-day Munich, is really beside the point.

That’s not to say that there are no distinctions to be made within the minutae of experience to be had in each, of course. But the moralistic tone that is often taken against the allegedly more ‘escapist’ of the two still betrays at least a hint of lazy thinking.

For all that the more grimily realist fiction can illuminate and raise awareness — political awareness which, it must be said, is thinner on the ground(s) of that genre’s more navel-gazing counterparts — the fantastic acts as an extension of that experience.

Let’s give voice to what’s easier to defend here, for starters. Boundary-pushing works of the fantastical — the kind you’ll find among the likes of Kafka, Angela Carter or David Cronenberg — will exaggerate and amplify with the aim of exploring loftier points. The flinty realists are largely on the side of these non-escapist works of the fantastical.

Tom Sturridge as Morpheus/Dream in the Netflix adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman

Tom Sturridge as Morpheus/Dream in the Netflix adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman

But I would submit that even the most reactionary or nostalgic of fantasy works can have a purpose which isn’t simply redolent of intellectual vacuity or laziness, of a kind of distracted quietism that numbs the intellect and reduces its consumers to little more than sludge.

At the end of the day, even the knockiest of Tolkien knock-offs will be better for your mental hygiene than hours spent doomscrolling through the social media platform/s of your choice… and the degree of actual, conscious choice involved in that experience is questionable to begin with.

Because if distraction from reality is what makes fantasy such an ‘irresponsible’ intellectual pursuit, what is the doomscrolling impulse of the 24/7 news cycle, which has now emigrated beyond the relatively confined space of the television screen to also latch themselves onto our mobile phones? (Yes, Gibson and Cronenberg have been warning us of this with grotesque gusto for decades).

Haunted by this reality, I submit that anything which promotes immersion of any kind is a better and more meditative alternative.

***

Re-read of the season: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany

Currently reading: The Broken Sword by Poul Anderson

April 6, 2022

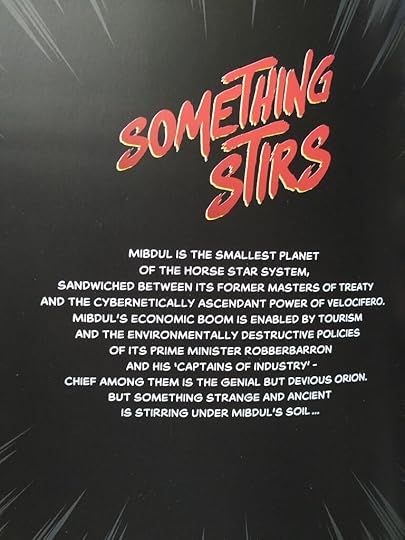

It’s time to take a trip to MIBDUL…

A young girl whose mother has committed suicide discovers she’s able to commune with ancient monsters, who have emerged from their slumber to wreak havoc on the over-developed, tiny planet of Mibdul.

‘Mibdul’ is a six-issue comic book mini-series written by myself, illustrated by Inez Kristina and published by Merlin Publishers. The first issue will be launched at Kixott on 14 April, and the party starts at 19:30. Said party will feature a signature cocktail, and early-comers will be rewarded by an open bar tab courtesy of our long-suffering but beloved publisher.

Now that the logistical stuff’s out of the way…

I’d like to point out that, much like the last few posts to appear on this sporadically updated page, Mibdul is a tribute to Marsascala. The place served as a hometown for both Inez and myself while we worked on the book, and the very idea for the comic came about after it was announced that the unspoilt patch of seaside land at Zonqor Point was given away to a Jordanian construction company.

The ‘American University’ project thankfully never panned out as per its worst threats, but at that point I needed a vent for the helpless rage that came over me and many others.

It is, sadly, a rage that continues to crop up every now and again, whenever the construction lobby which de facto rules the country proposes a fresh monstrosity.

We all protest in the ways we know best. At least, we should be allowed to. From each according to their ability. And my own tend towards a love of genre fiction. As such, Mibdul taps into the ‘space fantasy‘ popularised by Star Wars, with a dollop of cosmic horror and the freewheeling surrealism of Euro-comics.

Mibdul will be published as a monthly six-issue series, starting from April and running through to September. We hope to see you at the launch for Issue 1. But in the meantime, do avail yourselves of the pre-publication offer, to have each issue delivered to your door upon release, at a discounted price.

September 2, 2021

The Village by the Sea | Marsascala Under Attack (Again)

Having lived in Marsascala between 2015 and 2020 and seeing the sleepy-but-bustling former fishing village once again become a target for suffocating over-development, I’ve decided to look back on some of my impressions and memories of the town, partly motivated by simple nostalgia, partly by an urge to help myself understand just why the authorities and the business class so often make it a point to single out Marsascala in their ongoing drive towards uniform devastation. This is the third blog post in an erstwhile series.

So we had a sea view.

Sullied at the edges of your peripheral vision by clumsily placed solar panels, sure, but it was there. It greeted you each morning and provided a balm in the evening during summer – then, in all of the expected ways – and during winter it allowed for a showcase of nature’s fury as the waves crashed in violent foam over the promenade.

It remains the one undeniable perk we both miss very much now that we’ve relocated from Marsascala to Rabat a year ago. No longer being able to wake up and smell the sea, taking in its blue-on-blue hue, can’t be brushed off so easily. You can only be stoic about so much.

Thinking back on this, it’s the Marsascala dawn that really stands out in the memory. The sea view is the sea view, yes, but it really comes into its own in the morning, when it allows you to greet the day with a particular sense of accessible, graspable majesty. You visualise the opposite bay like a slowly-loading act of creation: the sight of the water hits you first, with the promenade and the dotted boats appearing gradually, replotting themselves into the scenery. A wide blue expanse, from eyeline to sublime horizon, would have its meditative perks too, of course.

But there’s something charming in the way the sea is stoppered by the twist of the promenade, at least viewed from our former spot in Zonqor. (One of my smallest – and so, most precious – delights was spotting buses work their way across the promenade road from our terrace. A miniature reminder of a system that somehow, with all its faults, still manages to work. To serve people.)

You realise it all the more when you actually go down and see for yourself – when you experience the promenade as a participant, not just a mere spectator. The slippy-slide of the moss-strewn walk down by what is a de facto boat yard… a brief shot of pure vernacular beauty, sadly interrupted too soon by the parked cars that insist on crowding you before you’re allowed to emerge to the main walk, facing the church.

But for a while, it’s like you’re transported into a scene redolent of the early 20th century: the promise of an effortlessly charming Mediterranean village fulfilled. Old houses fronted by streetlamp-flanked benches, for lovers to share pizza and beer purchased from very close by. Room for families to spread out a formica table and benches for a multi-generational gathering of card games and barbecues. And despite the independent flurry of boats that frame and flank it all, room enough for an old man with a bad leg to dull his pain with diligent exercise – a refreshing dip into the sea, after which he dries himself off seated upright by the wall, before working up the strength to head back home.

Regular sights for me, but morning and evening. But it all goes by in a few seconds: a pocket of fantasy, a near-literal blink of an eye. Because after that, you’re either back to the sea-view blocks by the road, where you’ll get to enjoy the more traditional pleasures of a rocky beach which will – eventually – be joined by the Zonqor fields we fought very hard to retain back in 2015. Or you’re more likely to head about your business in the opposite direction, marching your way to the promenade and its string of shops and restaurants, along with a nail technician and real estate agents’ office (or two. Pretty sure there were at least two).

This is where the true ‘life’ of Marsascala could be said to begin: the trigger of the daily churn of people and business. In the absence of a concentrated square, we get a stretched out one: the promenade serves as a gathering point for people and a stopping point for fruit & veg trucks, at least until it sheds the skin of a village square and becomes the ‘leisure’ promenade expected by convention.

The transition point for this is the small area by the traffic lights which lead to the bus terminus – or more accurately, to the recently-refurbished, multi-generational family restaurant Grabiel – where the barriers to the sea are briefly opened up; a place that serves as a small parking space and which in winter leaves plenty of leeway for flooding – you’re often forced so skip over and otherwise creatively manouevre through large puddles of pooled and brackish sea water.

From there forward, the communal spirit becomes more solitary and leisurely. You grab an ice cream and march forward towards St Thomas Bay and its environs; an area of true sublime beauty very much compatible with tourist postcards. But it also exists in the shadow of a fallen ruin: the old Jerma Palace Hotel, now a crumbling reminder of mismanagement and institutional dithering, but also a pro-active breeding ground for some of the island’s more interesting street art, and the location for many a low-budget music video.

Its neighbour, the St Thomas Tower, taps into a similar vein of neglect and decadence: it’s thankfully no longer a pizzeria, but any historical glory it may boast feels diminished by its flaking exterior, and its proximity to the far more imposing Jerma ruin. Still, both structures are also notable for their cat colonies, often seen crossing indistriminately from one side of the street to the other, making this cat lover’s heart skip a beat each time.

If our walk from Zonqor is undertaken during the evening, this is the point at which we often begin to turn back home. That, or we extend our walk past St Thomas Bay itself – to overlook the beach during magic hour and forgive this island and its people its many shortcomings.

Read previous: Distance Does Not Mean Protection

August 24, 2021

Distance Does Not Mean Protection | Marsascala Under Attack (Again)

Having lived in Marsascala between 2015 and 2020 and seeing the sleepy-but-bustling former fishing village once again become a target for suffocating over-development, I’ve decided to look back on some of my impressions and memories of the town, partly motivated by simple nostalgia, partly by an urge to help myself understand just why the authorities and the business class so often make it a point to single out Marsascala in their ongoing drive towards uniform devastation. This is the second blog post in this erstwhile series.

*

Marsascala always struck me as one of the few villages or towns in Malta whose borders are actively separated by clear distances.

Most of Malta’s localities exist on parallel and intersecting lines – like the twin cities of Besźel and Ul Qoma in China Mieville’s fantasy-noir novel The City and the City. Plant yourself at any border on the island and you’ll likely find yourself facing or tailing a couple more. Not so with Marsascala.

The road that extends from its closest Southern cousin of Zabbar feels like a proper ‘highway’ between one town, city, village and the next. Neither is it terribly feasible to walk to nearby villages through its other end – a one-hour trek to its more decorated fishing village cousin of Marsaxlokk is certainly beautiful in the right conditions, but impractical in others; opting to walk to the equidistant Zejtun is neither a pretty nor safe proposition.

And trudging through the ‘pedestrian’ highway to Zabbar (and nearby Birgu) would be pointless – it’s a strip of land designed exclusively for cars, and all the ramblers would get out of it would be inhaled fumes.

But this isolation equals neither boredom nor tranquility, much as I sometimes wished that to be the case. Marsascala is ‘bustling’ in various senses of that loaded word. A fishing village turned summer-house location for local families turned expat haven turned half-hearted tourist spot.

A few decent restaurants have popped up in recent years, but the provision of overall services remains on the sketchy side. No need to pine for the mercilessly ‘sleek’ counterparts of Sliema and St Julian’s – which would be uncomfortable for a host of related or vaguely-related reasons – but moving to the more centralised and quieter area of Rabat has quite literally brought home the benefits of the more traditional village structure.

Marsascala, on the other hand, is marked by long stretches and disproportionate distances, only to be stoppered by sprawl on its edges and contours. The long promenade cuts a swathe across Zonqor Point and St Thomas Bay on either end, and both of them are then burdened by apartment blocks – snails carrying a shell of cramped-together dwellings. In between are the shops, restaurants and yes, some villas with ‘unobstructed views’ for those who can afford them.

It’s a mish-mash rearing for change – or rather, for streamlining and ‘completion’ – a completion which in Malta signals only oblivion.

This is why a raggedly hybrid place like Marsascala is so vulnerable to attacks of ‘development’. Its liminal state – between warm summer dwelling and tourist hub, between fishing village and cool hangout – is an affront, an offence.

And its edges must be smoothened into the choking nothingness that Transport Malta, the Planning Authority and – crucially – the status-hungry populace want. Anything that just “sits there” is a waste of time and resources.

The poverty of the Maltese school system – a reheated version of utiliatrian British methods based on rote learning and mechanised exams – means there is no oxygen left to cultivate a sense of enrichment and belonging in leaving things just as they are, and enjoying them as such.

Which is why we are left to suffer under the yoke of public officials such as the Planning Authority’s executive chairperson Martin Saliba, who equate the zombie-brained expansion of ugly urban sprawl with an inevitable drive towards a vaguely-defined “modern era” for Malta.

Distance is what isolates Marsascala, and what makes it vulnerable. You reach it after a long stretch, and you find it to be all alone. You imagine it cupped in the palm of a distracted sea-goddess.

No UNESCO-protected fortifications defend it from attack, alas.

Read more: Resistance & Self-Compassion: The Case of (and for) Marsascala

August 20, 2021

Resistance & Self-Compassion: The Case of (and for) Marsascala

The seaside village of Marsascala which served as my home for roughly six years up until recently has once again become a beacon of environmental resistance in Malta, after a government-sponsored proposal to choke its bay with a vulgarly gigantic yacht marina has led to a near-unanimous uproar among both activists and locals.

If the root of the complaint were not so depressing, such a united front would have been inspiring to witness. After all, it’s a ripple that follows on from a similar wave or organised dissent back in 2015, when the ‘American University of Malta’ was proposed on the same village’s outskirts.

This was to be a beacon legacy project for disgraced former prime minister Joseph Muscat and his chosen coterie of movers and shakers in the political and business world – a Malta-Jordan collaboration built on virgin land with a pre-packaged, pre-purchased American university syllabus aiming to attract further ‘high net worth’ individuals to spend their money in Malta and Gozo.

That the project is now little more than a shadow of its proposed self stands as something of a feather in the cap of the same environmentally-conscious protestors who took to the streets to fight it tooth and nail.

We should remember this. We often denigrade ourselves for not doing enough, or for doing too little, too late. Or for not accepting that the status quo will carry on in its usual churn regardless, and give into apathy and a sense of futility as a consequence.

But the long view is that while short-term battles may be lost and while, on the environmental front at least, the political and business hegemony may continue to treat us with utter contempt (whose unholy alliance is still not taboo, even after it was a direct contributor to the murder of a journalist), taking a stand still matters.

There’s a lot to scoff at in the current generation’s earnest, somewhat pat ideas on how to make life marginally more tolerable – as was the case for generations past. But I would insist on encouraging everyone involved in this ‘resistance’ to exercise a degree of self-compassion.

Following the concerted uproar, the American University of Malta was set to be split into two campuses – one ostensibly to remain in a ‘reduced’ capacity on Marsascala’s Zonqor Point, the other to occupy an historic colonial building at the harbour town of Bormla. The extension back to Zonqor will only happen if the Bormla campus fills up. This remains an unlikely outcome, given how student count amounted to under 100 by late 2019.

Activists should allow themselves not just self-compassion here, but an enlivening jolt of sadism too. This is a call to laugh at the critically wounded near-corpse of a mortal enemy. To cackle in the face of at least one of these offenders – who cackle at our earnest attempts to counter them nearly 24/7, as more and more obscenities crop up at every corner.

It may not be the most noble emotion to indulge, but we deserve it. If anything, it will give us fuel for the next fight… which will always be around the corner.

*

I’ll be putting out some follow-up posts to this one, in which I’ll finally be dumping some memories and impressions of the town. Don’t expect amusing trivia and historical rigour. But feel free to expect pretty much anything else. I know I am.

August 12, 2021

A Vipers’ Pit | Press Coverage & Reviews

With A Vipers’ Pit (Is-Sriep Regghu Saru Velenuzi) enjoying a healthy run at Eden Cinemas, I thought I’d compile a little guide for prospective viewers before they take a chance on our political thriller-family drama-literary adaptation.

Response has been better than anything I had every hoped for: reviews ranges from ecstatic to ecstatically disappointed, but indifference was never the least bit part of the equation. For a low-budget debut based on a beloved book which attempts to treat national wounds, it’s just the kind of response you want.

So here’s a handily collated list of some previews, interviews and even reviews that the film has already amassed so far.

*

Interviews with director-producer Martin Bonnici Martin Bonnici. Photo by James Bianchi/MaltaToday

Martin Bonnici. Photo by James Bianchi/MaltaTodayEden Cinemas Interviews: Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 (video)

*

Cast & Crew Interviews8.97 Bay interview with actors Chris Galea Joseph Zammit, Gianni Selvaggi and Erica Muscat and myself.

LovinDaily interview with Erica Muscat (video)

*

Chris Galea as Noel Sammut PetriReviews

Chris Galea as Noel Sammut PetriReviews Ad Lib Talk (video)

*

…aaand we’ve even made it to Malta’s ‘most serious’ news site.

The film is currently showing at Eden Cinemas. Book your tickets here.

A Vipers’ Pit | Viewer Guide for the Second Weekend

With A Vipers’ Pit (Is-Sriep Regghu Saru Velenuzi) heading into its second weekend at Eden Cinemas, I thought I’d compile a little guide for prospective viewers before they take a chance on our political thriller-family drama-literary adaptation.

Response has been better than anything I had every hoped for: reviews ranges from ecstatic to ecstatically disappointed, but indifference was never the least bit part of the equation. For a low-budget debut based on a beloved book which attempts to treat national wounds, it’s just the kind of response you want.

So here’s a handily collated list of some previews, interviews and even reviews that the film has already amassed so far.

*

Interviews with director-producer Martin Bonnici Martin Bonnici. Photo by James Bianchi/MaltaToday

Martin Bonnici. Photo by James Bianchi/MaltaTodayEden Cinemas Interviews: Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 (video)

*

Cast & Crew Interviews8.97 Bay interview with actors Chris Galea Joseph Zammit, Gianni Selvaggi and Erica Muscat and myself.

LovinDaily interview with Erica Muscat (video)

*

Chris Galea as Noel Sammut PetriReviews

Chris Galea as Noel Sammut PetriReviews Ad Lib Talk (video)

*

The film will be showing at Eden Cinemas until at least 17 August. Book your tickets here.