Teodor Reljic's Blog, page 10

February 24, 2017

February Updates #3 | Awguri, Giovanni Bonello; Toni Erdmann; Brikkuni & Unintended

Yep, I had said February was a wonderfully busy month for me, and it’s proven to be so right until the end.

Awguri, Giovanni Bonello launch

[image error]

First off the ground is the most recent — the launch of Awguri, Giovanni Bonello at Palazzo Pereira in Valletta, which I’ve spoken about earlier and which was commemorated at a very posh — but otherwise very pleasant — party organised by Merlin Publishers and the other ‘conspirators’ involved in this festschrift for Judge Giovanni Bonello, who turned 80 last year and who apart from a distinguished legal career, penned his own micro-histories which Merlin cherry-picked through and passed on to ten selected authors.

Judge Bonello was nice enough to say — in a moving speech at the event — that we lent an extra dimension to his otherwise “two-dimensional” figures; but all I’ll say is that I certainly had great fun with my story ‘Bellicam machinam vulgo petart appelatum’, which allowed me to meld the history of an already-sensational character — Caterina Vitale — with Gothic pastiche. Being encouraged to channel the likes of Frankenstein and Dracula into something of my own certainly felt like opening a fount that was dying to be opened; as was being able to indulge in an ornate, baroque literary style (whose convoluted sentences proved to be something of a challenge to read out loud during the launch party, however!)

Click here to read more about the book

***

Toni Erdmann | Film Review

[image error]

Peter Simonischek and Sandra Hüller play a distant-but-constricting father-daughter pair in Maren Ade’s critically acclaimed comedy Toni Erdmann

“Growing tired of their distant relationship following yet another whirlwind visit from his go-getting daughter, Winifred decides to pay a surprise visit to [his daughter] Ines in Bucharest. When his plan for enforced bonding fails, Winifred changes tack – and persona – by adopting a wig and fake teeth and introducing himself as ‘Toni Erdmann’ to Ines’ friends and colleagues… while a horrified Ines looks on as her father threatens to compromise her professional and social standing.

“While this sounds superficially amusing and perhaps even creepy, what in fact develops is a touching study in second chances. For Winifred, this is something of a last-ditch effort to make up for any mistakes he may have made while raising Ines – his bumbling nature throughout suggests there may have been many – while Ines is suddenly given a chance to inject some humanity in her ambition-driven, corporate existence.

“Ade’s deceptively loose directorial style leaves plenty of room for the excellent performances by Simonischek and Hüller to shine through, building the film at a humane pace that ensures its emotional peaks feel entirely earned, and not forced into place by a script aiming for formulaic pressure points.”

Click here to read the full review

***

Rub Al Khali by Brikkuni | Album Review

[image error]

Brikkuni debuting songs from Rub Al Khali during a concert at the Manoel Theatre in October 2015 (Photo: Chris Vella)

“Because [Brikkuni frontman Mario Vella’s] expressions of anger and disillusionment, harsh and inflected with dark humour as they sometimes are, always come from a place of earnest emotion. Vella’s not one for protective irony or tongue-in-cheek games: his political, social and critical observations are always made plain for all to see – something that holds true for both his oft-legendary Facebook posts and the content of Brikkuni’s songs in and of themselves.

“And with Rub Al Khali he has taken his earnest approach into what is arguably the most vulnerable place imaginable. Brikkuni’s third album is a concept album, of sorts. A concept album about the dissolution of a ten-year relationship. Yeah.”

Click here to read the full review

***

Unintended | Theatre Review

[image error]

Close shave… too close: Mariele Zammit and Stephen Mintoff. (Photo: by Christine Joan Muscat Azzopardi)

“But ironically, for all the hard-ons it seeks to inspire in our beleaguered protagonist, the second half of the play is remarkably limp as far as narrative drive is concerned. After poor Jamie is drugged and drugged over and over again and seduced into having aggressive – though it must be said, not entirely unsatisfying – sex with Diana, the play abandons its previously established vein of cheeky black humour and simmering tension in favour of a terminal descent into tired ‘torture porn’ territory.

“That Buckle is a fan of the in-yer-face theatre genre will surprise absolutely nobody – at least, not those who have followed the trajectory of Unifaun Theatre with even a fleeting sideways glance over its admirable run – and let’s face it, we all knew Unintended was heading towards a gory climax of some kind. But the problem is neither that the violence and degradation on display are ‘too much’, and neither, really, that this was a predictable move for the debut play by Unifaun’s founder and producer. The issue is one of simple story structure.”

Click here to read the full review

February 17, 2017

February Updates #2 | iBOy, RIMA, You Are What You Buy & the latest in Mibdul (again)

Questioning consumption | You Are What You Buy

[image error]

It was interesting to hear what Kristina Borg had to say about her project You Are What You Buy, which takes an interdisciplinary approach to assessing the implications of shopping at the supermarket.

“One of the principal themes of this project is consumption – what and how we consume. This does not solely refer to food consumption; one can also consume movies, literature and more. However, in order to reach and engage with a wider audience I felt it was necessary to work in, with and around a place of consumption that is more universal and common for all. Let’s face it, whether it’s done weekly or monthly, whether we like it or not, the supermarket remains one of the places we visit the most because […] it caters for our concerns about sustenance and comfort.”

[image error]

Kristina Borg

“An interdisciplinary approach definitely brings together different perspectives and different experiences and […] it could be a way forward for the local art scene to show and prove its relevance to one’s wellbeing. I think it is useless to complain that the arts and culture are not given their due importance if as artists we are not ready to open up to dialogue, exchange and distance ourselves from the luxury that one might associate with the arts. Talking about experience instead of a product might be what the local art scene needs.“

Click here to read the full interview

Fixing the moment | Mohamed Keita and Mario Badagliacca

[image error]

The migrants living at the Belgrade Waterfront are using the beams of abandoned tracks (or tires or rubbish) against the temperatures below zero degrees and to produce hot water. Photo by Mario Badagliacca

Ahead of their participation at the RIMA Photography Workshops, I got a chance to delve into the dynamics of migration — particularly the problematic way in which migratory flows are portrayed through mainstream political discourse and the media — with Sicilian photographer Mario Badagliacca, who tapped into his experience of documenting the realities of migration — most recently in my own native Belgrade — as well as Ivorian photographer Mohamed Keita, who took a self-taught route to photography after traversing Africa to reach Italy.

The power of photography is to fix the moment. Psychologically speaking, there’s a difference between perceiving a ‘fixed’ image and a ‘moving’ image (as in a video, for example). The ‘fixed’ image constrains us to reflect on it in a different way. In my case, I want the images to serve as a spur for further questions – to be curious about the stories I’m telling. I don’t want to give answers, but raise more questions. – Mario Badagliacca

[image error]

Photography by Mohamed Keita

Click here to read the full interview

Film Review | iBoy — Netflix takes the info wars to the gritty streets

[image error]

Screams of the city: Tom (Bill Milner) finds himself plugged into London’s mobile network after being attacked by thugs in this formulaic but serviceable offering from Netflix

I had fun watching the ‘Netflix Original’ iBoy — not a groundbreaking movie by any means, but certainly a fun way to spend an evening in the company of Young Adult urban sci-fi that slots into formula with a satisfying click.

[image error]

Love interest: Maisie Williams

“iBoy is yet another example of British cinema being able to strip down genre stories to their essentials and deliver up a product that, while hardly brimming with originality, still manages to create a satisfying piece of escapist entertainment. From Get Carter (1971) down to Kingsman (2014), the Brits sometimes manage to upend their Stateside counterparts by just cutting to the chase of what works without the need to inflate their budgets with unnecessary star power and special effects, while also toning down on any sentimentality and drama at script stage.”

Click here to read the full review

Patreon essay | MIBDUL & ‘that uncomfortable swerve’

[image error]

Not exactly a ‘day job’ entry — though I wish it were — this month’s Patreon essay for our MIBDUL crowdfunding platform was all about me panicking over not having enough space to write out the story as I was planning it, and needing to make some drastic changes to accommodate this new reality.

“The thing about the detailed outlining of issues – and the rough thumbnailing of the pages in particular – is that, unlike the planning stage [in my journal], I approach them largely by instinct. This is the time when you have to feel your story in your gut, because you need to put yourself in the position of the reader, who will be feeling out the story in direct beats instead of painstakingly – and digressively – planned out notebook excursions. (To say nothing, of course, of the fact that the story needs to look good on the page – that the artwork needs the necessary room to breathe).”

Please consider donating to our Patreon page to access this essay and more

February 13, 2017

Frenzied box of stories | A Tiding of Magpies by Pete Sutton

[image error]

Getting a glimpse on an author’s evolution is always an intriguing prospect. Particularly when this happens through the lens of a short story collection, where variety is almost a necessary part of the experience, allowing you to see how the author manipulates various themes and points of view — all in the space of one compact volume.

The debut collection by Bristol-based writer Pete Sutton, A Tiding of Magpies, is something of an extreme example of this exercise in action, being a collection of just-about themed stories jumbled together, of varying length and varying genre category.

Although the overall arrangement of the stories — the book is published by Kensington Gore — may come across as a tad messy and haphazard as the reader weaves his way through the byways of Sutton’s frenzied imagination, there’s a raw and direct way to Sutton’s storytelling that will always command the reader’s attention.

Opening with a supernatural chiller about a pair of brothers — one of whom appears to be harbouring a malevolent form of telekinesis — with ‘Roadkill’, Sutton establishes himself as a writer capable of both getting at emotional pressure-points straight away to hook the reader in, while operating with a clear and unpretentious style on sentence-level that ensures you’re sucked in without having to look back.

Working through the collection, I’ve often found myself in that rare but wonderful position — the best possible, I think, for a reader — where the lines just rolled their way over my eyes while my brain was busy making pictures.

Sutton’s capability and flexibility as a writer can never really be doubted as you sort through this frenzied box of stories

The downside of this mode of effortless writing — at least, in Sutton’s case — is that it can sometimes feel a tad too abrupt. Some of the stories in A Tiding of Magpies more or less fit into the ‘flash fiction’ mode, with a few of them being effective evocations of a particular mood or idea — ‘Dismantling’ and ‘Not Alone’ are excellent chillers that take full advantage of the constricted form — but the likes of ‘The Cat’s Got It’ feel like little more than doodles thrown into the collection for the hell of it.

Nevertheless, Sutton’s capability and flexibility as a writer can never really be doubted as you sort through this frenzied box of stories. There’s wacky humour (‘An Unexpected Return’), far-future sci-fi (‘The Soft Spiral of a Collapsing Orbit’), experimental mood pieces (‘Sailing Beneath the City’), metafictional escapades (‘Five for Silver’; ‘Christmas Steps’) along with a plethora of horror and plain (or not so plain) weirdness spun in a generous and freewheeling collection.

The final story in the collection, ‘Latitude’ stakes a very particular claim that is bound to reverberate in the reader’s mind’s eye — being something of an exercise is psychogeography for its author’s beloved Bristol, a mid-life crisis tale as well as a story of encroaching horror whose cockroach-infested undertones brought to mind Nathan Ballingrud’s The Visible Filth.

Though rough around the edges as an overall editorial product — perhaps a bit of pruning and re-arranging could have made the collection feel more powerful and cohesive — A Tiding of Magpies certainly announces Pete Sutton as a writer of talent and variety, and I certainly look forward to reading more from him… in whichever genre future work of his slots under. If any at all, that is.

[image error]

[image error]

January 30, 2017

February Updates: Shakespeare, historical fiction & the latest in MIBDUL

It’s not February yet but it will be soon enough, and in these times of uncertainty and stress I figured it wouldn’t be so bad to start listing (and celebrating) some of things I’m excited about for the near future.

First up, though — something from the very recent past.

MIBDUL: latest process video from Inez Kristina

Done for our $10+ Patrons, I’m really loving this fully narrated process video from Inez, detailing how she goes about structuring a page in general, and page 10 of MIBDUL’s first issue in particular.

Of course it would be thrilling for me to see my words come to life as pictures at any stage, but seeing the page at such an early, raw stage has its own particular pleasures. For one thing, it’s good to see that, raw as the sketches are at this stage, Inez has a firm grip of both the geography of the spaces and the overall mood of the characters.

[image error]

This certainly goes a long way to put me at ease as the writer of MIBDUL — knowing that the script will be rendered in a way that is both faithful and impressive in its own right — but it’s also heartening to discover that Inez understands the vibe of MIBDUL in a very intimate way. Successful communication is the key to all collaboration, and I think we’re riding a good wave here.

[image error]

It’s also interesting to hear Inez speak about how her approach to the pages has changed of late; namely that instead of painstakingly rendering each page one by one, she’s decided to start sketching out several pages all at once, so as to get a better sense of how the storytelling should flow without getting bogged down by details and drained by the process too early.

[image error]

Funnily enough, it mirrors my own turn with the writing of late: for similar reasons — to speed up the process in a way that matches the flow of the story — I’ve decided to go ‘Marvel method’ on the latter half of scriptwriting process; partly because dialogue is the most challenging part of it all for me, and partly because I think seeing the page laid out by Inez will inspire me to write dialogue that is both succinct and relevant to the flow of the story.

Please consider following our Patreon journey — it would mean a lot to us. Really.

Awguri, Giovanni Bonello: Gothic pastiche for an illustrious judge

[image error]

Like MIBDUL, my contribution to the bi-lingual historical fiction volume Awguri, Giovanni Bonello — to be launched at some point in February in honour of the same judge’s 80th birthday — is yet another collaboration with Merlin Publishers, who have been a pleasure to work with ever since they oversaw the publication of my debut novel, TWO.

To say that this was a fun commission would be a massive understatement. Basically, the judge being honoured by this volume — the poshest birthday present imaginable, am I right? — was also something of an historian, and the personages he wrote about were ‘assigned’ to each of us writers to spin a fictional yarn out of. And I will forever be grateful to Merlin’s head honcho Chris Gruppetta for giving me what is possibly the most sensational and salacious character of the lot: Caterina Vitale, a Renaissance-era “industrial prostitute”, torturer of slaves and — paradoxically — beloved patron of the Carmelite Order.

Of course, I went to town with this one. High on the then still-ongoing Penny Dreadful — and hammering out the short story to the haunting and dulcet tones of that show’s soundtrack by the inimitable Abel Korzeniowski — I liberally crafted something that is both a pastiche of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, all set against the backdrop of a Malta fresh from the Great Siege.

I’m looking forward to getting my mitts on this gorgeous-looking book — designed by Pierre Portelli with illustrations by Marisa Gatt — if only because I look forward to checking out how my fellow TOC-mates tackled the raw material of Bonello’s historical output.

The Bard at the Bar: Debating Shakespeare

[image error]

On February 8 at 19:00, I will be moderating a panel discussion on whether the works of William Shakespeare are relevant to the Maltese theatre scene — and Malta at large — and if so, how to make them feel more accessible and vital to the widest possible audiences.

The brainchild of actor, director and journalist Philip Leone-Ganado of WhatsTheirNames Theatre, the debate will, significantly, take place at The Pub in Archbishop Street, Valletta, aka the place where Oliver Reed keeled over and died after consuming an obscene amount of alcohol while on a break from filming Gladiator back in 1999.

More recently, the venue has accommodated the very first edition of ‘Shakespeare at the Pub’ — a production of the Two Gentlemen of Verona directed by Ganado himself last year — and another one is in the offing for 2017.

[image error]

Two Gentlemen of Verona at The Pub, Valletta (WhatsTheirNames Theatre, March 2016). Photo by Jacob Sammut

The lively, unpretentious and game production certainly felt to me like a step in the right direction as far as making Shakespeare more vibrant and relevant was concerned, so I think the Pub is as good a place as any to keep that inspired momentum going with a good discussion.

And it should certainly make for a satisfying debate, given that apart from Ganado himself, the panel will be composed by James Corby (Head of Department of English at the University of Malta and hence offering some academic weight to the proceedings), Polly March (director of the upcoming MADC Shakespeare summer production — the ritualised and established intake of Shakespeare for the island) and Sean Buhagiar, head of the newly-established Teatru Malta and someone deeply concerned with nudging the local theatrical scene out of its usual comfort zones.

So do come along to hear us talk. And feel free to shout your questions and comments over a pint, or ten. Just don’t crank it up to Oliver Reed levels, please.

January 28, 2017

Re-encountering the Weird: The Outer Dark & the continuing relevance of Weird Fiction

By now those interested in the literary form in question will have at least heard about the landmark episode of The Outer Dark podcast that came out not too long ago, where host and writer Scott Nicolay gathers together some highly significant players in the realm of weird fiction for a bumper-size — that is, two hour — discussion about what the ‘weird’ is and where it’s headed.

For me, the conversation nudged a series of ideas and associations that I’ve allowed to become dormant for quite some time. Fact is — discovering weird fiction was an important landmark for me in many ways, but I’ve felt it wane from hungry obsession to doggedly pursued intellectual interest and now down to a fading interest of late, but the podcast in particular yielded some answers as to why that may have been the case.

Weird Fiction was the spur that led me to set up Schlock Magazine: a collective group exercise in creative writing for like-minded scribblers here in Malta that then blossomed into something of a bona-fide (though always ‘4dLuv’) online publication, and whose reins I’ve now handed over to my dear sister.

Around the same time, however, I also wrote my Master’s dissertation on ‘the New Weird’; by then already at least somewhat boxed away and shorn of any real new-ness, enabling me to study it as a bracing exercise in literary experimentation, if not an enduring literary tradition or even sub-genre in its own right.

Slippery and just about impossible to define — the brilliant and imposing tome that is Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s ‘The Weird’ anthology attests to that with girth and panache — the Weird is also, necessarily, alienating.

[image error]

And for the longest time, its deliberate alienation also signaled for me an invitation to fully embrace the uncanny and disturbing sides of our perception. It made the Weird a thing of endless, edgy possibility. Where other genres would skate towards tradition — or its degraded cousin, convention — the Weird would flourish in its unique fungus-growth of strangeness. And where the field of mainstream literature — so my reasoning went — would often spin compelling narratives in fine language, they would still not descend so deep into the rabbit hole of strangeness that the very best exemplars of the weird reveled in.

Of course, sweeping assumptions like these are largely borne out of laziness, which is why they don’t yield any critical rewards in the long run. But apart from the inaccuracy of such statements, the supposed undercurrent of the Weird — its commitment to evoke a sense of alienation in the reader without offering up any narrative explanation or even, really, any sense of catharsis — ceased to be engaging for me after a while.

Thing is, we’ve all been left bummed out, nervous and scrambling for answers these past couple of years and months. It’s safe to say that the world’s an uncertain place wherever you are right now, and even though an argument could be made for that always having been the case (again, depending where you are), we can all agree that we’ve reached something resembling Consensus Panic at this point, for reasons that I barely need to specify.

Coupled with my own natural tendency towards anxiety — which I tend to treat with a healthy and regular dose of Marcus Aurelius and journaling — it felt as though the Weird was becoming an indulgence too far. To wit: why would I want to actively pursue fiction whose primary and perhaps only priority is to jolt you out of any remaining peace of mind you may still be in possession of?

Partly because I wanted to give my own writing a keener sense of structure — in response to some very valid criticism I received for my debut novel, and because I’ve made it a point to try and craft MIBDUL to a more or less ‘classic’ framework — I’ve caught myself edging away from the Weird as I try to learn the rules first before breaking them, as it were.

But listening to the Outer Dark podcast reminded me not just of the variety that’s intrinsic to the weird — Han Kang’s blistering award-winner The Vegetarian was discussed as a truly Weird candidate, for one thing — but also that its main aim is not to disorient, but to cohere.

[image error]

Responding to some of Nicolay’s prompts, Ann VanderMeer in particular seized upon a characterisation of the Weird that I’ve often neglected, but that I now feel should have been a point of focus all along. Namely, that the Weird stems from a primordial desire to confront the Unknown.

And it’s not just limited to the verbiage and racism of someone like HP Lovecraft, or the less politically problematic but no less arch work of someone like Algernon Blackwood. It is found in Kafka, it is found in Calvino and it is found in any number of international literary traditions who don’t shy away from letting the true strangeness at the core of human life run amok.

The Weird is many things, yes. And one of these things happens to be the ability to look at the unknown in the face and to acknowledge it as such. Not to deny it, or to repurpose it within a more rationalised framework. But to let it sit just as it is, and bleed its beautiful spool into the work.

There might be a sense of fear or at least trepidation in leaping into that kind of aesthetic program. But as this great edition of the Outer Dark reminds us, it’s one filled with as much strange fruit as it is with disquieting vistas into the black hole of the indifferent universe.

December 28, 2016

Designing the thrill ride | Editor and Publisher Ross E. Lockhart on Eternal Frankenstein

Ross E. Lockhart

A hard-working and eminently likeable presence in the field of speculative fiction small press, editor and publisher Ross E. Lockhart takes a seat at the Soft Disturbances lounge to chat about Eternal Frankenstein – a 16-story tribute to Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking science fiction and Gothic horror classic – which he edited this year for Word Horde. He also delves into what makes this increasingly essential genre fiction publishing house tick, before letting us in on the Frankenstein story of his dreams…

[image error]

First off; why Frankenstein, and why now? Mary Shelley’s text has been a touchstone for quite some time, so what made you think that now is the right moment to put together an anthology like Eternal Frankenstein?

This summer was the bicentennial of ‘The Year Without a Summer’, wherein massive climate instability was caused by the 1815 eruption of Mt Tambora in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), blanketing the Northern Hemisphere in miserable weather. A young English couple – Percy Shelley and Mary Godwin – decided to escape the apocalyptic rain and constant cold (and majorly dysfunctional families) by staying with a friend in Switzerland, Lord Byron.

[image error]

Mary Shelley (1797-1851)

Percy and Mary brought along Mary’s cousin Claire, and Byron was attended by his personal physician, John Polidori. One stormy night, as the five sat indoors, reading ghost stories by firelight, Byron proposed a ghost story competition. That night, Mary had a dream that would inspire her to write Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which she would publish anonymously in 1818.

The book and its many adaptations fascinate me, and I believe the story is one of the most intricate and poignant myths of the modern era.

Beyond this anniversary, I’ve been a Frankenstein fan since I saw James Whale’s Universal films as a kid. The book and its many adaptations fascinate me, and I believe the story is one of the most intricate and poignant myths of the modern era. I also looked at things from a commercial standpoint, and I realized that (with the exception of Steve Berman’s Daughters of Frankenstein: Lesbian Mad Scientists) it had been a long time since anybody had published an all-original Frankenstein-themed anthology.

As with other Word Horde anthologies I’ve had the pleasure of reading in the not-too-distant past, Eternal Frankenstein is a finely crafted piece of editorial work, with stories clearly selected to intensify certain through-lines and motifs: teenage angst, anti-communist hysteria and the reanimated automaton as a cog in the military machine, to mention just a few. How did you set about identifying these themes? And to deepen a bit further: why do you think the legacy of Shelley’s text accommodates these themes and images in particular?

Editing an anthology is a lot like building Frankenstein’s monster. You start by digging through graveyards, finding pieces, and seeing how those pieces fit together. You take chances. You invite authors whose work you enjoy, and you say “show me what you’ve got”. You tweak and you fine-tune and you experiment and arrange, and eventually a creature takes form, comes to life, and shambles out into the countryside, demanding a mate.

I work with authors who are constantly striving to produce the best possible work, and I’m willing to push those authors to do better.

[image error]

Frankenstein by Bernie Wrightson

Given that Shelley’s novel continues to hold such an influential sway over our culture, was it actually easier to amass short fiction of adequate quality and variety for Eternal Frankenstein, when compared to other anthologies you’ve put together? Or did the process pan out in more or less the same way?

Eternal Frankenstein is my seventh anthology, and while these books are always challenging in their own way, and a lot of work, I’ve developed a system that keeps things on track in a more-or-less smooth way. I work with authors who are constantly striving to produce the best possible work, and I’m willing to push those authors to do better.

[image error]

Frontispiece for the 1831 edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Illustrated by Theodore Von Holst (Steel engraving; 993 x 71mm)

Ultimately, I want stories that are going to resonate with readers, stories readers will remember for the rest of their lives. One of the things that inspires me about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is that she was trying to write a story that would be as powerful and memorable as anything written by Percy or Byron. And I think she managed, with Frankenstein, to outshine both of them.

There is an analogy I frequently use when talking about anthologies: The Thrill Ride

And on that note, do you have any iron-clad principles you adhere to when putting together Word Horde anthologies?

That it be fun. There is an analogy I frequently use when talking about anthologies: The Thrill Ride. Like the designer of a roller coaster or carnival dark ride, the anthologist is directing a reader’s experience. You carefully arrange things, the climb, the fall, the sudden turn, the loop. You seed in shocks and scares. You direct the reader’s view. But you also have to keep things moving. Always moving. Sure, readers jump in, read stories out of their intended sequence – that’s a reader’s right. But one must never forget that a book is best read from cover to cover, each story in conversation with the ones before, each setting the stage for the next story to come.

Word Horde is certainly becoming something of a standard-bearer for the genre small press. How would you say it’s evolved to this point, and what are your future ambitions for it?

I’m really happy with the way that Word Horde has been received. I’m currently publishing five books a year, picking projects carefully, and getting work out there that has something to say and shakes up the complacency so common in by-the-numbers genre fiction. If you’ve enjoyed what I published in 2016, you’re going to love what’s coming in 2017. And Word Horde may be a small press but we’ve got big ideas, so stay tuned.

[image error]

Still from Frankenstein Conquers The World (1965)

Finally… what would your own Frankenstein story look like?

Just off the top of my head, remember Monster Island from the Godzilla films? I’d like to tell the story of Frankenstein Island. All the various cinematic Frankenstein’s monsters – Charles Ogle, Boris Karloff, Glenn Strange, Koji Furuhata, Phil Hartman, Robert De Niro –building a civilization on a remote island. Though I’m not sure whether that society would be a utopia, dystopia, or something in between.

Check out my Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon in all its entirety for reviews of each of the stories in the collection.

Please consider donating to the Patreon for MIBDUL – Malta’s very first serialized comic!

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon | Table of Contents

Over the past couple of months, I’ve been reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I tackled the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method was be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These were presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification. You can find the complete linkstorm to all of the reviews just below. Enjoy!

[image error]

Torso, Head, Heart by Amber Rose-Reed

Baron von Werewolf Presents: Frankenstein Against the Phantom Planet by Orrin Grey

They Call Me Monster by Tiffany Scandal

Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice by Damien Angelica Walters

Sewn Into Her Fingers by Autumn Christian

Orchids by the Sea by Rios De La Luz

Frankenstein Triptych by Edward Morris

The Human Alchemy by Michael Griffin

Postpartum by Betty Rocksteady

The New Soviet Man by G.D. Falksen

The Un-Bride; Or No Gods and Marxists by Anya Martin

Wither On the Vine; Or Strickfaden’s Monster by Nathan Carson

The Beautiful Thing We Will Become by Kristi DeMeester

Mary Shelley’s Body by David Tempelton

Please consider donating to our Patreon to help us make Malta’s first serialised comic, MIBDUL. Thanks!

December 13, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #14 | David Templeton

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I tackled the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method was be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These were presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification. Now, please enjoy the final review of the series.

[image error]

Mary Shelley’s Body by David Templeton

And now, at the very end of Lockhart’s anthology, we get a focus on the body — the ultimate body as far as we’re concerned: that of Mary Shelley, the originator of all of the things we’ve been discussing so far, and one of the most fecund imaginations of the Romantic and/or Gothic high point of literature — an unexpected force to be reckoned with considering her young age when she composed her key work, and her compromised — some would say relentlessly tragic — private life.

David Templeton’s novella — it is in fact the longest piece in Eternal Frankenstein — makes for a fitting conclusion to this varied and comprehensive tribute to the legacy of Shelley’s most famous work, by forcing a fictionalised version of the beleaguered author to confront her many demons, seemingly as a final goodbye before parting the world for good.

In turn, the story also forces us, the readers, to come face-to-face with Frankenstein’s many themes and emotional implications; some of which weigh on the very real side of disturbing: not just in their Gothic power to enthrall and terrify by dint of grotesque detail and atmosphere, but also because of the tortured psychological place they come from, the biographical backbone of which Templeton makes it a point to unpeel, explore and embroider further to craft his novella.

[image error]

Mary Shelley (1797-1851)

The setting is as baldly Gothic as they come, though, with Shelley’s disembodied form rising from her Bournemouth grave to settle a score initially mysterious to her. What follows is something of a rambling confessional whose shape, like the Creature Shelley constantly makes reference to in various ways, could have used some trimming and re-arrangement.

While the concept is a worthwhile one — and, again, a perfect note to end the anthology on — that does come with a real emotional pay-off in the end, Templeton’s decision to go over some of the key moments of Shelley’s life, as well as key passages of Frankenstein, will come across as a tad tiresome to those of us familiar with the scenes and passages in question.

What’s even more problematic is that Templeton doesn’t really do all that much to upend expectations, either: the obvious connection between the death of Mary’s mother while giving birth to her is made yet again, while Mary waxes lyrical about her Creature while condemning Victor Frankenstein as a coward at best, a clueless, callous bastard at worst.

But the digressive nature of it all is part of the point — this is a kind of mental Groundhog Day for our poor Mary, and if nothing else, Templeton demonstrates a key understanding of what makes Shelley’s work tick. And neither would it be fair to say that he succumbs entirely to boilerplate interpretations of the text; Victor Frankenstein’s failure is eventually revealed to be Mary’s own, in connection with the death of her first unborn child.

Ultimately, here we have a story about bodies — the bodies we encounter and the body that we inhabit, and all of the complexity that that implies once we’re forced to stop taking them for granted. This complexity falls down on Frankenstein’s Creature like a ton of bricks since he is first brought into the world, and so it serves to offset our own lives at any given moment. And, finding a suitably tortured test subject in Mary Shelley, Templeton uses the opportunity to zone in on these moments at various points in time: from bodies freshly born and vulnerable, to those sickly and decaying… and everything in between.

The body is all we have. And at some point, we were all Frankenstein’s Creature. At some point, we will BE Frankenstein’s Creature yet again. This, above all, is why Shelley’s legacy endures, and why it’s likely to help create more anthologies like Eternal Frankenstein in the years to come.

Read previous: Kristi DeMeester

Stay tuned for an interview with Ross E. Lockhart, the editor of Eternal Frankenstein!

November 26, 2016

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #13 | Kristi DeMeester

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

The Beautiful Thing We Will Become by Kristi DeMeester

There might be something to the niggling assumption that, Mary Shelley having penned Frankenstein when she was merely nineteen years old helps to lend the book with the urgent, neurotic charge that it the necessary flipside to the life-and-death energy that characterises youth.

The ‘outsider’ status of the creature is the biggest element in favour of that interpretation, but I would argue that there’s also something to Victor Frankenstein’s initially obsessive, but ultimately brittle commitment to his project that speaks to the young person’s unease of matching their dreams — and nightmares — to the cold slap of reality.

As we’ve already seen, Lockhart himself appears to be very sensitive to this, what with two back-to-back stories from Eternal Frankenstein capitalising on the legacy of Shelley’s original story by juxtaposing it to a high school context, with inspired results.

The strand is however also picked up by Kristi DeMeester, though her take is less about the social dynamics of the high school than it is about the harried bonds of love that develop among young friends at that delicate stage. More importantly, it’s about how just a small push into stranger territory can alter these young lives, seemingly for good.

Our Frankenstein’s Creature is one Katrina, and the narrator is a hanger-on best friend who grows curious about Katrina’s — initially slight — hints of bodily modification. But family history steps in to ensure this morphs into a full-on obsession: after her father abandons her mother in pursuit of a younger (and crucially, slimmer) woman, the narrator is thrown into a calorie-counting frenzy by a newly weight-conscious single mother.

This serves to give a keener edge to her attraction to Katrina, which is really an attraction towards the grisly experiments her kindly but eccentric father performs on his daughter.

DeMeester writes from the point of view of the narrator’s eerie emotional state, and as such the narrative voice isn’t judgmental, but fully immersed in a world that sees self-destruction as a form of salvation and horrific acts of bodily modification by a demented patriarchal figure as something to embrace. Needless to say, the effect is disturbing. But since we’re so close to the narrator all the way through, we achieve a strange sort of empathy with her journey.

DeMeester morphs disgust into madness and back into love, leaving us to observe the journey with nervous awe.

Read previous: Nathan Carson

November 22, 2016

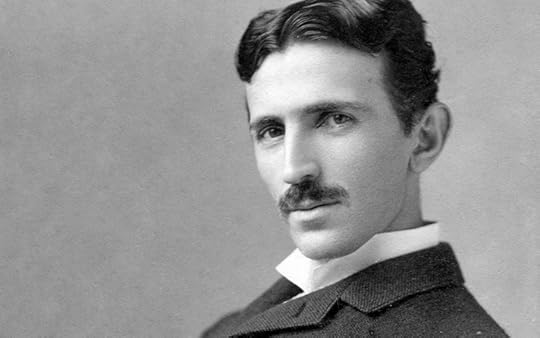

Eternal Frankenstein read-a-thon #12 | Nathan Carson

In the coming weeks, I will be reviewing the new Word Horde anthology Eternal Frankenstein, edited by Ross E. Lockhart. As was the case with my read-a-thon of Swords v Cthulhu, I will be tackling the anthology story by story, and my reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Wither on the Vine; Or Strickfaden’s Monster by Nathan Carson

One of the fun things about the kind of spirited pastiche that tends to animate anthologies like Eternal Frankenstein is that the fun can easily be had from various sources, or at the expense of literary and historical figures that can plausibly be co-opted into the overall schema of the legacy left behind by Mary Shelley’s original text.

Nathan Carson’s tale certainly makes the most of this tendency, meshing not one, but two key historical characters — of, it must be said, varying degrees of prestige — into the overall mix of a Frankenstein-inspired story.

The titular character of Kenneth Strickfaden is inspired by the real-life figure who brought unforgettable Hollywood props from some classic Hollywood movies — most famously, as it happens, the lightning-powered device that brings the Creature to life in James Whale’s groundbreaking adaptation of Shelley’s text.

Kenneth Strickfaden (1896-1984)

Because his car breaks down in a desert canyon near Utah, Strickfaden finds solace in the company of the enigmatic Mr Baldwin, who offers him lodging and car repairs in exchange for his help with some left-field science experiments he is conducting in his home; Strickfaden’s admittedly amateur reputation as a quirky tinkerer preceding him thanks to a one-off appearance in the pulp magazines of sci-fi pioneer Hugo Gernsback.

What follows is a decent into weird science as pushed into weirder extremes by particularly American religious convictions, with Strickfaden discovering more than he should about what Baldwin’s been up to — specifically, how his community aims to ‘treat’ some of its ailing women — before being given the opportunity to cross paths with one of his idols: the one and only Nikola Tesla.

Tesla’s reputation as a real-life ‘mad scientist’ animated by Romantic ideals — and beaten down by the capitalist machine — renders him particularly vulnerable to appropriation by modern speculative fiction writers. But while the Tesla in Carson’s story still comes to us draped in the same legendary aura, his depiction is far less flattering — and certainly less heroic — than one has come to expect. Here, Tesla remains an eccentric genius who produces results, but he’s also as much in love with money as he is with his creations, and doesn’t seem particularly concerned with human life beyond its impact on his experiments.

Bright spark: Nikola Tesla

In short, he is the true Victor Frankenstein of the story — we could say that Baldwin is initially placed as something of a red herring — but because Carson tells the story in a slow-burning, old-timey tone that exudes wry irony, Tesla is presented as a blackly comic figure rather than an out-and-out villain.

It’s clear that Carson is having fun creating a situation in which Strickfaden and Tesla get to meet: it’s a kind of ‘origin story’ for Strickfaden, actually. And in fact, Baldwin’s religious community is presented as little more than an easy-to-ridicule gathering of desperate, credulous people who get what they bargained for when they meddle with the natural order.

Which is ironic, because whereas the Victor Frankenstein of Shelley’s original text was always keenly aware of the fact that his work may be an affront to God, Baldwin and his followers have convinced themselves that what they’re doing runs in exact tandem with God’s wishes. Stuck in the middle is their sly enabler — Tesla — and Strickfaden, an accidental hanger-on who ends up helping both sides.

In short, it’s a story about that peculiarly American trait of improvising with newfangled phenomena — be they scientific innovations or religious sects — and then doing your best to profit from them, or at least survive with all your limbs intact when it all goes to shit.

Read previous: Scott R. Jones