Dan Ariely's Blog, page 45

September 7, 2012

Call for Artists to Respond to Research on Self-control

Artists from around the world are invited to attend a discussion on self-control entitled ”Restraining Order: The Art of Self-Control” as the next part of the “Artistically Irrational” exhibition series on Wednesday, September 26th at 7 PM EST. (Artists who do not live within driving distance of Durham, NC will be able to watch the forum streaming online.)

Interested artists should RSVP to the curator, Catherine Howard, at artisticallyirrational@gmail.com by Monday, September 24th by 9 PM.

After the forum, artists interested in creating artwork in response to the research will submit a 1-page proposal and 2-3 digital images of past work. To be considered, applications must be submitted by Friday, October 5th at 9 PM.

Artists will be notified if they are selected to participate by Monday, October 8th and will receive a $100 stipend to complete their piece. There is no limitation to the style or media of pieces created for “Restraining Order,” but the exhibit includes an exercise in self-control embedded in the artistic process. All selected artists will be required to work on their pieces for the entire period leading up to the due date and will send weekly photos to document the progression of the piece. All completed art works must be received by Friday, December 7th.

Artwork created for “Restraining Order” will be on display at the Center for Advanced Hindsight from December 14th, 2012 to February 22nd, 2013 with a reception on Saturday, January 26th, 2013 from 6-9 pm.

Artists will retain all rights to their piece. Works will be returned to artists after the exhibit by March 15th, 2013. If the piece is purchased, the $100 stipend will be deducted from the purchase price.

Important Deadlines

September 26, 7pm — Forum at the Center for Advanced Hindsight

October 5, 9pm — Deadline to submit artwork proposal

December 7, 9pm — Drop-off deadline

January 26, 6–9pm — Opening reception at the CAH

September 5, 2012

Harvard and the politics of large-scale cheating

Harvard is known for many things, its rigorous academics, its crisp New England campus, its secret societies, and now, what may be the most extensive cheating scandal in Ivy League history. A total of 279 students are now under investigation for collaborating on a take-home exam, with the threat of a year’s expulsion hanging over their heads if found guilty.

Matthew Platt, professor of the course in question (Introduction to Congress), brought the tests before the school’s administration after noticing similarities on a few of the exams, and the investigation mushroomed from there. Students were not permitted to work together on the exam (officially), but now there’s a lot of talk about the instructions, the expectations, and the questions themselves being unclear. I would bet that there are a number of aspects to this situation that led to such a widespread web of cheating.

In general, lack of clarity in expectations is a great instigator of dishonesty, after all, when no one tells you what you can and can’t do, it becomes much easier to decide for yourself what probably is and isn’t okay. For instance, it might seem that asking a peer what he or she thinks a question means if the wording is unclear is pretty reasonable. Then, naturally, that discussion of intent might lead to what the answer could be. In this case, the instructions seem fairly clear, stating that “students may not discuss the exam with others.” However, it appears that the professor cancelled his office hours before the tests were due, which would make it a lot more difficult to clarify any questions. This makes for easy justification.

Also, the subject of the class was Congress, which is itself an institution shot through with ambiguity and famous for its lies and liars. Extensive discussion of corruption could easily engender more dishonest behavior in those taking part (in psychology we call it priming, where we expose participants to a stimulus that alters their behavior as a result, for instance, asking people to do math problems when we want to induce logical thinking). It’s hard to imagine a better primer for dishonesty than a class on Congress. Maybe one on modern financial institutions.

Moreover, people generally agree that cheating in the social domain is often acceptable—we call them little white lies. Like when a friend asks how she looks in something and you say “great!” when you really should say “passable”; that’s often excused from the realm of dishonesty. Or another friend asks what you think of his new girlfriend, and you say “she seems nice!” instead of “she seems boring and self-centered!” We tell these little lies to keep the peace. Yet we generally deny that this is acceptable in the business domain. If you ask your accountant how much money is in such and such an account, giving a number twice as high to make you feel better would be inexcusable. We need to consider that for students, the social and professional circles vastly overlap, which makes it more difficult to separate what’s permissible and what isn’t. This is not to absolve students who cheat, but it’s something to consider. Students often live in the same place they go to class, which is essentially their workplace. Their friends are also their colleagues, and their “bosses” (professors and TAs) are often their friends. All this blending makes can make lines of conduct a bit more indistinct.

None of this is meant to make light of the problem of cheating, or to imply that it’s excusable. But if we want to prevent such things from happening again, we need to think about not just the students, but also the system in which they live and operate. Thus, professors need to work on being crystal clear in instructions. Telling students, for instance, “speak to no one other than the professor or your TA about any aspect of the exam” leaves no gray areas. All that said, it will be interesting to see how things at Harvard shake out …

September 4, 2012

Announcing the winner of the “Title Peter Ubel’s Book” contest

Hello everyone. Thanks again to all of you who gave me ideas on titles for my new book, exploring the challenges of shared decision-making between doctors and patients. The book is officially on sale now, so I thought it would let you know who won the book titling contest.

I loved a bunch of your ideas, and forwarded about a dozen of them to my publisher.

As a lover of puns, I had to forward Scott Ware’s idea of “Drs. without Orders.”

I loved Johnny Hill’s suggestion: Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, and Doctors Are from Saturn. But I have always been partial to Pluto!

A responder named Terry suggested a great title: “Trust Me, We’re a Doctor.” That title does a great job of capturing the spirit of shared decision-making, which runs throughout my book.

But the winner is Jessica Margolin, who suggested a title which came very close to the one my publisher chose: Critical Decisions: How You and Your Doctor Can Make the Right Medical Choices Together.

I am totally excited about this book. It explores ideas I have been working on for over 15 years. In it, I tell stories from both ends of the stethoscope — stories of physicians and patients struggling to make tough choices together. There is a lot of of irrationality at play in these decisions too, sometimes exhibiting itself in ways you don’t see outside of medical encounters.

Read the book and you will not only understand your own thinking better—and gain insight into how you are likely to respond if or when you have a difficult decision to make—but you’ll understand your doctor better too!

Read the book and you will not only understand your own thinking better—and gain insight into how you are likely to respond if or when you have a difficult decision to make—but you’ll understand your doctor better too!

You can find more info on my website, including video previews of book chapters. Or just get the book, read it, and let your friends know what you think.

Thanks again for all your help!

Peter

August 31, 2012

Ask Ariely

Here’s my column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to askariely@wsj.com

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In your answer last week about splitting checks at restaurants, you noted that there is a “diminishing sensitivity as the amount of money paid increases.” I’ve noticed this in my own spending. I’ll go out of my way to save a buck and then spend an ungodly sum on some purse. Why is that? And how can I control it?

—Lembry

Diminishing sensitivity is a very basic way that our minds work across many domains of life. For example, imagine that you light up one candle in the middle of the night. This small amount of light will dramatically change your ability to see your surroundings. But what if you already have 10 lit candles and you add one more? Now it would not have much of an effect. The basic idea of diminished sensitivity is that our minds tend to register relative increase; we take any additional amount of stuff as if it were a percentage gain, not an absolute one.

Now, when it comes to money, we should think about it in absolute terms ($10 is $10 regardless of whether we are saving it from a dinner bill or from the price of a new car), but we don’t. We think about money in terms of percentages, too.

What can we do about it? It’s not easy, but we should try to fight this natural tendency. One method that I use from time to time is to take the amount of money that I am thinking about spending and ask myself what else I could get with it. For example, since I like going to the movies (and let’s say that the price of two tickets and popcorn is $25), I ask myself whether a given $25 of spending on a prospective purchase is worth more or less than the pleasure of going to the movies.

When framed this way, it doesn’t matter if the savings come from a dinner bill or a new computer—and it helps me to ask the question “What would I enjoy more?” in a more concrete way. So, the next time you are shopping for a new purse, try to measure its price in terms of another use for that money that you might value more.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have been on vacation for the last few days in New York City, and while reading your most recent book, on dishonesty, I have been wondering whether people behave more or less honestly on vacation.

—Julie

This is an interesting question, and (sadly) I don’t have any data to share with you on this topic. But here are a few ideas to consider:

Why might people on vacation be more honest? While on vacation people seem to be more relaxed with spending money, which suggests that the motivation to be dishonest for financial gain might be lower. On top of that, people on vacation are more often in a good mood, which they might not want to spoil by behaving badly.

Why might people on vacation be less honest? On vacation, the actions we take are in a new context. As they say, “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.” Also, the rules on vacation might seem less clear: What are the regulations for parking in San Francisco? How much should you tip in Portugal? Is it OK to take the towels from this hotel? This sort of wishful blindness can make it easier for us to misbehave while still thinking of ourselves as generally wonderful, honest people.

On balance, then, are vacationers more or less honest? I suspect that they are less honest—but I would love to be proven wrong.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is it about Internet communication—Facebook, Twitter, email—that seems to make people descend to the lowest common denominator?

—James

It’s easy to blame the Internet, but I think we see such behavior mostly because people generally gravitate toward trafficking in trivialities. Consider your own daily interactions. How much is witty repartee—and how much is the verbal equivalent of cat pictures? The Internet just makes it easier to see how boring our ordinary interactions are.

See the original article right here.

August 30, 2012

Dishonest Literature: A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan.

Every so often I come across a passage in a book where I read it and think, “yes, that’s exactly it!” (“It” being some element or motivation of human behavior that I’ve been thinking about and/or researching.) The following is one of these passages, from Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad. It hits many of the right notes when it comes to illustrating how we enable ourselves to act dishonestly.

It began in the usual way, in the bathroom of the Lassimo Hotel. Sasha was adjusting her yellow eye shadow in the mirror when she noticed a bag on the floor beside the sink that must have belonged to the woman whose peeing she could faintly hear through the vaultlike door of a toilet stall. Inside the rim of the bag, barely visible, was a wallet made of pale green leather. It was easy for Sasha to recognize, looking back, that the peeing woman’s blind trust had provoked her. We live in a city where people will steal the hair off your head if you give them half a chance, but you leave your stuff lying in plain sight and expect it to be waiting for you when you come back? It made her want to teach the woman a lesson. But this wish only camouflaged the deeper feeling Sasha always had: that fat, tender wallet, offering itself to her hand—it seemed so dull, so life-as-usual to just leave it there rather than seize the moment, accept the challenge, take the leap, fly the coop, throw caution to the wind, live dangerously (“I get it,” Coz, her therapist, said), and take the fucking thing.

“You mean steal it.”

He was trying to get Sasha to use that word, which was harder to avoid in the case of a wallet than with a lot of the things she’d lifted over the past year, when her condition (as Coz referred to it) had begun to accelerate: five sets of keys, fourteen pairs of sunglasses, a child’s striped scarf, binoculars, a cheese grater, a pocketknife, twenty-eight bars of soap, and eighty-five pens…

First we have Sasha’s rationalization—the owner of the purse is so silly and naïve that she deserves to have her belongings taken. Sasha isn’t just stealing money, she’s teaching the woman how to be more careful. How thoughtful!

On top of this, Sasha offers herself the excuse that stealing the wallet is exciting rather than immoral, similar to the way we can glamorize mobsters and mafia in the movies. We also see, through her discussion with her therapist, that she—at least up until that point—had not considered using the word “steal” for what she’d been doing. It’s easier to lie, cheat, and steal if we call it something else (improvising, exaggerating, borrowing, for instance).

Her avoidance of the proper term (“stealing”), in turn, is enabled by the fact that she’d stolen items that were not themselves monetary (how much is a cheese grater worth anyway). This is the same loophole that allows people not to consider taking office supplies from work stealing the way they would taking some money out of an office cash box. We see the therapist, consequently, trying to get her to accept the term stealing for her actions—in this way, he can nullify some of the rationalizations Sasha puts forth.

August 25, 2012

Alibis for Sale

Dear Dan,

Have you seen this website, and what do you think about it?

Thanks,

Joe

Ever since The Honest Truth about Dishonesty was published, people send me emails about strange things they come across related to dishonesty, like this one offering “alibis and excuses for absences as well as assistance with a variety of sensitive issues.” My response:

Dear Joe,

I’m sure you noticed that while the web site claims these “issues” could take many forms, a quick pass through the services offered suggests that those looking to “have a discreet affair” are the main clientele.

On the whole, the web site is constructed to look like any basic service provider, if you didn’t read the copy, you’d probably think it was for a legal or financial company (albeit one that declines to spend money on a decent web designer). There are pictures of smiling, happy people with headsets, waiting to fill your order. The site has tabs that will direct the interested customer to a list of services (everything from producing and sending fake airline tickets, impersonating hotel reception, and providing detailed seminar materials), a fee catalogue, and a list of affiliates. You probably also noticed the testimonials, which, interestingly, lack any specificity and are quite difficult to understand. Perhaps this is because discretion is the name of the game (it appears that people are unwilling, even in the testimonials they provide for their alibi agency, to say “thanks for making my affair possible!”). And finally, the slogan: “Empowering Real People in a Real World!” It’s downright uplifting! Until you realize that by empowering people they mean lying on their behalf.

I suspect that all these trappings, which make the site look normal and above board, go a long way in helping people patronize this agency. People can book an alibi the same way they would a plane ticket. And they see that lots of other people use the service, thanks to the testimonials, so why not them? I think the “real world” rhetoric also helps lull people’s possible objections; the idea is that this is how things work, in the real world, not a fairytale land of 100% honesty.

For my part, I’m left feeling a little depressed and worried about what new kinds of advertisements might pop up in my browser after looking at this page…

web site claims these “issues” could take many forms, a quick pass through the services offered suggests that those looking to “have a discreet affair” are the main clientele. And the services—they really cover all the bases—include everything from producing and sending fake airline tickets, impersonating hotel reception, and providing detailed seminar materials (so your spouse thinks you’re off learning how new tax laws affect your clients rather than laying by a pool with a non-colleague).

On the whole, the web site is constructed to look like any basic service provider, if you didn’t read the copy, you’d probably think it was for a legal or financial company (albeit one that declines to spend money on a decent web designer). There are pictures of smiling, happy people with headsets, waiting to fill your order. The site has tabs that will direct the interested customer to a list of services, a fee catalogue, and a list of affiliates. There are also plenty of testimonials, which, interestingly, lack any specificity and are quite difficult to understand. Perhaps this is because discretion is the name of the game (it appears that people are unwilling, even in the testimonials they provide for their alibi agency, to say “thanks for making my affair possible!”). And finally, the slogan: “Empowering Real People in a Real World!” It’s downright uplifting! Until you realize that by empowering people they mean lying on their behalf.

I suspect that all these trappings, which make the site look normal and above board, go a long way in helping people patronize this agency. People can book an alibi the same way they would a plane ticket. And they see that lots of other people use the service, thanks to the testimonials, so why not them? I think the “real world” rhetoric also helps lull people’s possible objections; the idea is that this is how things work, in the real world, not a fairytale land of 100% honesty.

For my part, I’m left feeling a little depressed and worried about what new kinds of advertisements might pop up in my browser after looking at this page…

August 20, 2012

Discuss The Honest Truth with me on Shindig: August 28th at 6 pm

I’m excited to announce my first foray into interactive online discussion with readers. On Tuesday August 28 at 6 pm you can join me in a discussion of The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty, and of course, whatever else comes up. Sign up here.

August 18, 2012

Parking, Paying, and Putting

Here’s my column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to askariely@wsj.com

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What should I do about parking? I have trouble deciding whether I should go for a paid parking lot straight away or drive around in the hope of finding free parking—but at the risk of wasting time.

—Cheri

This is a question about the value of your time. You need to figure out how much money an hour of fun out of the house is worth to you and compare that cost with the time it takes to find a parking spot. For example, if an hour out of the house is worth $25 to you, and searching for parking takes 30 minutes on average, then any amount less than $12.50 that the parking lot charges you is worth it. As the number of people in your car rises, the value of parking quickly also rises because the waste of time and reduction of value accumulate across all the people in your group.

Another computational approach is to compare the misery you feel from paying for parking with the misery you feel while seeking a spot. If the misery from payment isn’t as great as the unhappiness from your wasted time, you should go for the parking lot. But if you do this, you shouldn’t ignore the potential misery you would feel if you paid for parking and then found a free spot just outside your destination. Personally, the thought of time wasted is so unbearable to me that I usually opt for paid parking.

Yet another approach is to put all the money that you intend to spend on going out in an envelope in advance. As you’re on the way to the restaurant or movie theater, decide whether that money would be better spent on parking or other goods. Is it worth it to forgo that extra-large popcorn if paying for parking will get you to the theater on time? That makes the comparison clearer between what you get (quick parking and more time out) and what you give up.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When going to dinner with friends, what is the best way to split the bill?

—William

There are basically three ways to split the bill. The first is for everyone to pay for what they’ve had, which in my experience ends the meal on a particularly low point. Every person has to become an accountant. Given the importance of endings in how we frame our memories of experiences, this is a particularly bad approach. Rather than remembering how delicious the crème brûlée was, you may be more likely to remember that Suzie ate most of it even though you paid for half.

The second approach is to share the bill equally, which works well when people eat (more or less) the same amount.

The third approach, my favorite, is to have one person pay for everyone and to alternate the designated payer with each meal. If you go out to eat with a group relatively regularly, it winds up being a much better solution. Why? (A) Getting a free meal is a special feeling. (B) The person paying for everyone does not suffer as much as his or her friends would if they paid individually. And (C) the person buying may even benefit from the joy of giving.

Let’s take the example of two friends, Jaden and Luca, who are going out to their favorite Middle Eastern restaurant. If they were to divide the cost of the meal evenly, each would feel, say, 10 units of misery. But if Jaden pays, Luca would have zero units of misery and the joy of a free meal. Because of diminishing sensitivity as the amount of money paid increases, Jaden would suffer fewer than 20 units of misery—maybe 15 units. On top of that, he might even get a boost in happiness from getting to buy his dear friend a meal.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I play in a weekly nine-hole golf league. There’s one individual who constantly talks on his cellphone, moves around while others are putting and mostly ignores the courtesies of golf. He’s been asked to stop this behavior but continues with a bully attitude. How do I handle it?

—Wally K.

Though you might be tempted to rip the phone from his hands, throw it on the ground and bash it with your 9-iron, I would suggest another solution.

You could implement a new rule, whereby everyone else playing with you earns a mulligan (a “do over” shot) each time the bully talks on the phone. Getting constant negative feedback (in addition to giving everyone a performance boost) would probably whip him into shape. Just be sure to take the mulligans consistently, every time he’s on the phone, so that his behavior is reliably punished and the message sticks.

See the original article here.

August 15, 2012

Understanding Ego Depletion

From your own experience, are you more likely to finish half a pizza by yourself on a) Friday night after a long work week or b) Sunday evening after a restful weekend? The answer that most people will give, of course, is “a”. And in case you hadn’t noticed, it’s on stressful days that many of us give in to temptation and choose unhealthy options. The connection between exhaustion and the consumption of junk food is not just a figment of your imagination.

And it is the reason why so many diets bite it in the midst of stressful situations, and why many resolutions derail in times of crisis.

How do we avoid breaking under stress? There are six simple rules.

1) Acknowledge the tension, don’t ignore it.

Usually in these situations, there’s an internal dialogue (albeit one of varying length) that goes something like this:

“I’m starving! I should go home and make a salad and finish off that leftover grilled chicken.”

“But it’s been such a long day. I don’t feel like cooking.” [Walks by popular spot for Chinese takeout] “Plus, beef lo mein sounds amazing right now.”

“Yes, yes it does, but you really need to finish those vegetables before they go bad, plus, they’ll be good with some dijon vinaigrette!”

“Not as good as those delicious noodles with all that tender beef.”

“Hello, remember the no carbs resolution? And the eat vegetables every day one, too? You’ve been doing so well!”

“Exactly, I’ve been so good! I can have this one treat…”

And so the battle is lost. This is the push-pull relationship between reason (eat well!) and impulse (eat that right now!). And here’s the reason we make bad decisions: we use our self-control every time we force ourselves to make the good, reasonable decision, and that self-control, like other human capacities, is limited.

2) Call it what it is: ego-depletion.

Eventually, when we’ve said “no” to enough yummy food, drinks, potential purchases, and forced ourselves to do enough unwanted chores, we find ourselves in a state called ego-depletion, where we don’t have any more energy to make good decisions. So–back to our earlier question–when you contemplate your Friday versus Sunday night selves, which one is more depleted? Obviously, the former.

You may call this condition by other names (stressed, exhausted, worn out, etc.) but depletion is the psychological sum of these feelings, of all the decisions you made that led to that moment. The decision to get up early instead of sleeping in, the decision to skip pastries every day on the way to work, the decision to stay at the office late to finish a project instead of leaving it for the next day (even though the boss was gone!), the decision not to skip the gym on the way home, and so on, and so forth. Because when you think about it, you’re not actually too tired to choose something healthy for dinner (after all, you can just as easily order soup and sautéed greens instead of beef lo mein and an order of fried gyoza), you’re simply out of will power to make that decision.

3) Understand ego-depletion.

Enter Baba Shiv (a professor at Stanford University) and Sasha Fedorikhin (a professor at Indiana University) who examined the idea that people yield to temptation more readily when the part of the brain responsible for deliberative thinking has its figurative hands full.

In this seminal experiment, a group of participants gathered in a room and were told that they would be given a number to remember, and which they were to repeat to another experimenter in a room down the hall. Easy enough, right? Well, the ease of the task actually depended on which of the two experimental groups you were in. You see, people in group 1 were given a two-digit number to remember. Let’s say, for the sake of illustration, that the number is 62. People in group two, however, were given a seven-digit number to remember, 3074581. Got that memorized? Okay!

Now here’s the twist: half way to the second room, a young lady was waiting by a table upon which sat a bowl of colorful fresh fruit and slices of fudgy chocolate cake. She asked each participant to choose which snack they would like after completing their task in the next room, and gave them a small ticket corresponding to their choice. As Baba and Sasha suspected, people laboring under the strain of remembering 3074581 chose chocolate cake far more often than those who had only 62 to recall. As it turned out, those managing greater cognitive strain were less able to overturn their instinctive desires.

(Photo: PetitPlat)

This simple experiment doesn’t really show how ego-depletion works, but it does demonstrate that even a simple cognitive load can alter decisions that could potentially have an effect on our lives and health. So consider how much greater the impact of days and days of difficult decisions and greater cognitive loads would be.

4) Include and consider the moral implications.

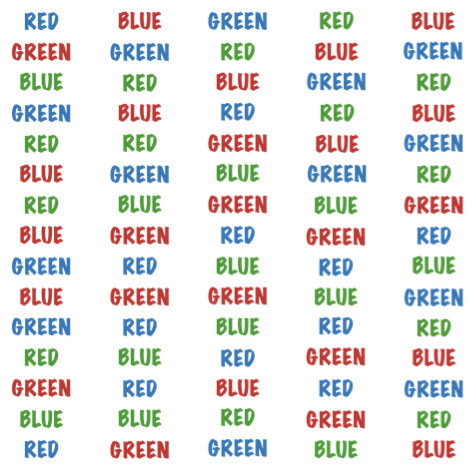

Depletion doesn’t only affect our ability to make good decisions, it also makes it harder for us to make honest ones. In one experiment that tested the relationship between depletion and honesty, my colleagues and I split participants into two groups, and had them complete something called a Stroop task, which is a simple task requiring only that the participant name aloud the color of the ink a word (which is itself a color) is written in. The task, however, has two forms: in the first, the color of the ink matches the word, called the “congruent” condition, in the second, the color of the ink differs from the word, called the “incongruent” condition. Go ahead and try both tasks yourself…

The congruent condition: color matches word.

The incongruent condition: color conflicts with word.

As you no doubt observed, naming the color in the incongruent version is far more difficult than in the congruent. Each time you repressed the word that popped instantly into your mind (the word itself) and forced yourself to name the color of the ink instead, you became slightly more depleted as a result of that repression.

As for the participants in our experiment, this was only the beginning. After they finished whichever task they were assigned to, we first offered them the opportunity to cheat. Participants were asked to take a short quiz on the history of Florida State University (where the experiment took place), for which they would be paid for the number of correct answers. They were asked to circle their answers on a sheet of paper, then transfer those answers to a bubble sheet. However, when participants sat down with the experimenter, they discovered she had run into a problem. “I’m sorry,” the experimenter would say with exasperation, “I’m almost out of bubble sheets! I only have one unmarked one left, and one that has the answers already marked.” She explained to participants that she did her best to erase the marks but that they’re still slightly visible. Annoyed with herself, she admits that she had hoped to give one more test today after that one, then asks a question: “Since you are the first of the last two participants of the day, you can choose which form you would like to use: the clean one or the premarked one.”

So what do you think participants did? Did they reason with themselves that they’d help the experimenter out and take the premarked sheet, and be fastidious about recording their accidents accurately? Or did they realize that this would tempt them to cheat, and leave the premarked sheet alone? Well, the answer largely depended on which Stroop task they had done: those who had struggled through the incongruent version chose the premarked sheet far more often than the unmarked. What this means is that depletion can cause us to put ourselves into compromising positions in the first place.

And what about the people, in either condition, who chose the premarked sheet? Once again, those who were depleted by the first task, once in a position to cheat, did so far more often than those who breezed through the congruent version of the task.

What this means is that when we become depleted, we’re not only more apt to make bad and/or dishonest choices, we’re also more likely to allow ourselves to be tempted to make them in the first place. Talk about double jeopardy.

5) Evade ego-depletion.

There’s a saying that nothing good happens after midnight, and arguably, depletion is behind this bit of folk wisdom. Unless you work the third shift, if you’re up after midnight it’s probably been a pretty long day for you, and at that point, you’re more likely to make sub-optimal decisions, as we’ve learned.

So how can we escape depletion?

A friend of mine named Dan Silverman once suggested an interesting approach during our time together at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, which is a delightful place for researchers to take a year off to think, plan, and eat very well. Every day, after a rich lunch, we were plied with nigh-irresistible desserts: cheesecake, chocolate tortes, profiteroles, beignets—you name it. It was difficult for all of us, but especially for poor Dan, who was forever at the mercy of his sweet tooth.

It was daily dilemma for my friend. Dan, who was an economist with high cholesterol, wanted dessert. But he also understood that eating dessert every day was not a good decision. He contemplated this problem (along with his other academic interests), and concluded that when faced with temptation, a wise person should occasionally succumb. After all, by doing so, said person can keep him- or herself from becoming overly depleted, which will provide strength for whatever unexpected temptations lie in wait. Dan decided that giving in to daily dessert would be his best defense against being caught unawares by temptation and weakness down the road.

In all seriousness though, we’ve all heard time and time again that if you restrict your diet too much, you’ll likely to go overboard and binge at some point. Well, it’s true. A crucial aspect of managing depletion and making good decisions is having ways to release stress and reset, and to plan for certain indulgences. In fact, I think one reason the Slow-Carb Diet seems to be so effective is because it advises dieters to take a day off (also called a “cheat” day–see item 4 above), which allows them to avoid becoming so deprived that they give up entirely. The key here is planning the indulgence rather than waiting until you have absolutely nothing left in the tank. It’s in the latter moments of desperation that you throw yourself on the couch with the whole pint of ice cream, not even making a pretense of portion control, and go to town while watching your favorite tv show.

Regardless of the indulgence, whether it’s a new pair of shoes, some “me time” where you turn off your phone, an ice cream sundae, or a night out—plan it ahead. While I don’t recommend daily dessert, this kind of release might help you face down challenges to your will power later.

6) Know Thyself.

(Image: AnEpicDay)

The reality of modern life is that we can’t always avoid depletion. But that doesn’t mean we’re helpless against it. Many people probably remember the G.I. Joe cartoon catch phrase: “Knowing is half the battle.” While this served in the context of PSAs of various stripes, it can help us here as well. Simply knowing you can become depleted, and moreover, knowing the kinds of decisions you might make as a result, makes you far better equipped to handle difficult situations when and as they arise.

This blog originally appeared on Tim Ferriss’ blog, here.

August 10, 2012

Aug 28th at 6 PM EST

On Aug 28th at 6 PM EST I will try a new tool for online discussions

So — if you want to chat about dishonesty and have time, join me:

http://www.eventbrite.com/event/38109...

Dan Ariely's Blog

- Dan Ariely's profile

- 3930 followers