Dan Ariely's Blog, page 46

August 10, 2012

Cheating in Online Courses

A recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education suggests that students cheat more in online than in face-to-face classes. The article tells the story of Bob Smith (not his real name, obviously) who was a student in an online science course. Bob logged in once a week for half an hour in order to take a quiz. He didn’t read a word of his textbook, didn’t participate in discussions, and still got an A. Bob pulled this off, he explained, with the help of a collaborative cheating effort. Interestingly, Bob is enrolled at a public university in the U.S., and claims to work diligently in all his other (classroom) courses. He doesn’t cheat in those courses, he explains, but with a busy work and school schedule, the easy A is too tempting to pass up.

Bob’s online cheating methods deserve some attention. He is representative of a population of students that have striven to keep up with their instructor’s efforts to prevent cheating online. The tests were designed in a way that made cheating more difficult, including limited time to take the test, and randomized questions from a large test bank (so that no two students took the exact same test).

But the design of the test had two potential flaws: first, students were informed in real time whether their answers were right or wrong; second, they could take the test anytime they wanted. Bob and several friends devised a system to exploit these weaknesses. They took the test one at a time, and posted the questions together with the correct answers in a shared Google document as they went. None of them studied, so the first one or two students often bombed the test, but students who took the test later did quite well.

When we hear such stories of online cheating, the reasons for this behavior seems rather simple: It doesn’t take a criminal mastermind to come up with ways to cheat on a test when there’s no supervision and the entire Internet is at hand. Gone are the quaint days of minutely lettered cheat sheets, formulas written on the underside of baseball cap bills, sweat-smeared key words on students’ palms. Now it’s just a student sitting alone at home, looking up answers online and simply filling them in.

While we can probably all agree that cheating in online courses is easier to pull off than in a physical classroom, I suspect that this simple intuition is far from the whole story, and that e-cheating is more than just a increased ease of getting away with it.

When my colleagues and I have examined the effects of being caught on dishonesty, we found that by and large changing the probability of being caught doesn’t really alter the level of dishonesty. In one of our experiments we asked two Master’s students at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev named Eynav, who is blind, and Tali, who has normal sight, to take a cab back and fourth between the train station and the university twenty times. We chose this route for a particular reason: if the driver activates the meter, the fare comes out to around $7 (25 NIS). However, there is a customary rate on this route that costs around $5.50 (20 NIS) if the meter is not activated. Both Eynav and Tali asked to have the meter activated every time they caught a cab, regardless of whether the drivers informed them of the cheaper customary rate. At the end of the ride, the women would pay the fare, wait a few minutes, then take another cab back to where they started.

What we found was that Tali was charged more than Eynav, despite the fact that they both insisted on paying by the meter. Eynav quickly supplied us with the explanation behind this curious phenomenon. “I heard the cab drivers activate the meter when I asked them to,” she told us, “but before we reached our final destination, I heard many of them turn the meter off so that the fare ended up close to 20 NIS.” This never happened to Tali. What’s more, many other experiments with undergraduates yielded similar results. What these results suggest is that simply making the situation such that people cannot get caught does not automatically lead to higher levels of dishonesty.

So if it’s not necessarily the fear of getting caught, what might be the reasons for increased cheating? Based on our research, I would propose that the primary reason is the increased psychological distance between the dishonest act and its significance, and between teacher and student. The difference a little distance can make is rather impressive. Take the results from a study of around 10,000 golfers who were asked—among other things—how likely golfers were to cheat by moving the lie of a ball by 4 inches through various means: by nudging it with the golf club; by kicking it; or by picking it up and moving it. What these golfers told us was that 23% of golfers would likely move a ball with their club while only 14% and 10% would move it by kicking it and picking it up, respectively. What this tells us is that the extra distance provided by the club allows for twice as much cheating as the unavoidably conscious and culpable act of picking up the ball and moving it.

What does this have to do with cheating in online courses? Online classes are by definition taken at a distance, from the comfort of the student’s home where they are removed from the teacher, the other students, and the academic institution. This distance doesn’t merely allow room for people to get away with dishonest behavior; it creates the psychological distance that allows people to further relax their moral standards. I suspect that this aspect of psychological distance, and not simply the ease of pulling it off, is at the heart of the online cheating problem.

There is another important reason why we should care whether the cause for online dishonesty is due to its ease or to a change in the perceived moral meaning of the action. If online cheating is simply a matter of a cost-benefit analysis, we can assume that over time online universities will find ways to monitor and supervise students and this way prevent such behavior. However, if we think that the root cause of online cheating is more relaxed internal morals, then time is working against us.

Let’s think for a minute about illegal downloads. Have you ever downloaded a song or TV show illegally? How badly do you feel about it? When I ask my students these questions, almost all of them admit to having plenty of illegally downloaded files on their computers—and they don’t feel badly about it. As it turns out, dishonesty lies on a continuum: there are behaviors we feel badly about, which is where our own morality holds us back. But as cheating in a particular domain becomes more commonplace, the negative feelings associated with it decrease until we don’t really feel badly at all.

Let’s return to Bob and to cheating in online courses. This kind of behavior in online classes worries me because it is becoming more pervasive, and once we reach a point of moral indifference, it is nearly impossible to change this behavior. I don’t think we’ve reached this point yet, so we need to work as hard as we can to counteract the trend toward dishonesty. Otherwise what’s often considered an important tool for democracy in education could be made worthless.

August 5, 2012

Starting Fresh.

We lie. We cheat. We bend the rules. We break the rules. And sometimes, as we’ve seen in Greece, it all adds up. But, remarkably, this doesn’t stop us from thinking we’re wonderful, honest people. We’ve become very good at justifying our dishonest behaviors so that, at the end of the day, we feel good about who we are. This tendency is only getting worse, and, as innocent as it may seem, the consequences are becoming more apparent and more serious.

Cheating has less to do with personal gain than it does self-perception. We need to believe that we’re good people, and we’ll do just about anything to maintain that perception. Sometimes, this means behaving in ways that align with our sense of what is right. Other times, it means crossing that line, but turning a blind eye to our behavior, or rationalizing it in some way that allows us to believe it’s OK.

Let’s say your friend, who is not looking their best, asks you how they look, and you don’t want to hurt their feelings, so you lie. You fudge it. You don’t necessarily say, “Wow! You’ve never looked better,” but you don’t tell them the full truth. And you have no problem rationalizing your fib: It’s the right thing to do, because you would never want to hurt your friend’s feelings. Perhaps you used more neutral complimentary terms, or didn’t look them in the eye at that particular moment. These sorts of details would make it easier to justify your well-intentioned lie, and help you sleep at night without giving it a second thought.

The same kind of self-deception applies to wider-scale cheating, although the motivations are usually different. In more professional scenarios, our dishonesty is typically fuelled by the desire for wealth or status, rather than concern for the reputation of others. Greed is a powerful motivator.

About two months ago, American businessman Garrett Bauer was sentenced to nine years in prison for insider trading. Garrett was one of the people I had spoken to in researching the nature of dishonesty, and to see the consequences of his actions catch up to him that way was a brutal reminder of just how out of hand cheating can get. Garrett traded stocks on insider information for about 17 years. He started off small, as people tend to do, and never considered that he might get caught. As time went by, it got easier and easier for him to cheat the system free of guilt. But then he got caught, and now it’s too late to correct his mistakes.

That night, after his sentencing, I couldn’t sleep. I curled into the fetal position – the world looked terrible to me. I had spent the day before in New York giving talk after talk about cheating and dishonesty, how widespread they are, and how little appetite we have to start changing things. With all that cheating weighing on my mind, Garrett’s sentence was an additional terrible blow. It was overwhelmingly sad, and a very painful night.

The consequences of this sort of cheating are even more severe when the network of contagion is larger. We see this when we look at Greece, where masses of people have been cheating a little bit everywhere, and it’s added up. What this shows is just how contagious dishonesty can be. When we see somebody else cheat, especially if they’re part of our own, internal group, all of a sudden we figure out that it’s more acceptable to act this way. It’s not that the probability of our getting caught has changed – it’s that we’ve changed our mindset, convincing ourselves that the act itself is actually OK. At some point, you just think, “This is the way things are done,” and you go with the flow.

One woman from Greece recently told me that she was selling her apartment and she was considering whether to sell it legally (and pay taxes) or illegally (without paying taxes). She quickly recalled that she had bought it illegally, and that she was going to lose money if she would turn around and sell it legally – not to mention that in her mind she would be the only person in Greece paying taxes on real-estate property.

When everyone around you is cheating the system, what’s your motivation to be the one not playing along? And why change now? Why not make changes next month, or next year, instead?

This mentality is accentuated in Greece because it’s not just the everyday citizens who have been cheating – the government has been fudging the books. When cheating is that entrenched in a country, what can you do to stop it? It’s incredibly naïve to think that it will stop on its own. What Greece needs is something like the Reconciliation Act that South Africa adopted, focusing not on the travesties it has done to its people, but on starting fresh.

Every day, people are finding new and more creative ways to cheat, and to justify their dishonest behavior, regardless of the negative impact their actions might have on others. What’s most worrying about this trend is that we still fail to grasp the extent of our dishonesty. But it doesn’t have to be like this. If, on a global scale, we worked to understand the root of our dishonesty, and motivated each other to overcome it, we could do much better.

August 1, 2012

Swiss Army People

Plato once said that people are like dirt. They can nourish you or stunt your growth. This seems sage and reasonable, but I think people are more like Swiss Army knives (To be fair, Plato did not have the benefit of knowing of such a tool, so I don’t think I’m detracting from his comparison in the least). Swiss Army knives, as we all know, are incredibly versatile, and have a tool for almost any situation. Need to open a package—it’s got a knife! Sharing beers with friends on the beach—it’s got an opener! Have something in your teeth—there’s a toothpick for that! Need to do a little electrical work—it’s a got a tool that can strip wires! The downside is that Swiss Army knives are not particularly good for any specific purpose because any really intricate task is going to require much more specific tools.

People are a lot like Swiss Army knives from this perspective, and I am saying this with tremendous appreciation. A lot of the research in behavioral economists criticizes people for various ineptitudes: why we don’t save money, why we don’t exercise, why we text and drive. And it’s true, there’s a lot to criticize and a lot that goes wrong in our decision-making processes, but when you consider just how versatile we are, it’s very impressive. Essentially, we do a lot of things sort of OK. We can reason moderately well about money, we’re often pretty good with various relationships, we’re fairly moral, and most of the time we don’t kill ourselves or others. Not bad if you think about it this way!

Now, some people are more like the specialty tools, like post hole diggers, or lemon zesters, or cigar cutters; in these cases these individuals are truly excellent in certain domains. But often these people aren’t the best at navigating the world in a pragmatic fashion. There are often savants, like Kim Peek (the person that Rain Man is based on), who certainly can’t handle the day-to-day on their own, but have extraordinary abilities in other spheres. And plenty of geniuses have similar problems; take Bobby Fischer’s statelessness and detentions, or van Gogh’s famously self-detrimental tendencies and ultimate suicide. If everyone were like these folks, our species would surely be in peril. If people were all specialized, and could only think numerically, or long-term, or probabilistically, what would life be like? Neither rich nor long.

Of course these people provide inspiration and spur progress, and we admire and celebrate many of them (who don’t put their genius to antisocial use), but we should be grateful that most of us are more like Swiss Army knives.

July 30, 2012

Partisan Standards of Ethics

We say that politicians are slimy, our noses wrinkling with disdain – but is that the way we like them? It seems the answer depends on whether we agree with their agenda.

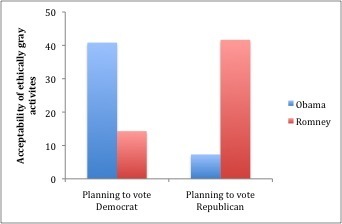

With the 2012 election steadily approaching, I wondered whether Democratic and Republican voters hold their preferred candidate and the opposing candidate to similar ethical standards.

To find out, Heather Mann (a graduate student working with me) and I conducted a little survey on American voters. Half the participants were shown a picture of Barack Obama, accompanied by the following paragraph:

“Sometimes, politicians engage in activities that are ethically ‘gray’ (e.g. providing favors to campaign donors, not fully disclosing information to the public, scheduling votes when politicians are away, etc.).

In your mind, how acceptable is it for Obama to engage in ethically gray activities in order to get elected and carry out his agenda?”

The other half of participants was shown a picture of Mitt Romney, and asked the same question about Romney’s ethical standards. All participants rated how acceptable it would be for the candidate to engage in ethically “gray” activities on a scale ranging from 0 (completely unacceptable) to 100 (completely acceptable).

Afterward, we asked participants whether they planned to vote for the Democratic or Republican candidate in the 2012 election. (Participants who indicated that they were voting for someone else or weren’t sure were excluded from our sample.)

What we found was that participants who were planning to vote Democratic indicated that Romney should be held to a fairly high ethical standard. Republican participants held a similar standard for Obama. But when participants happened to support the candidate in question – whether Obama or Romney – they indicated that ethically gray activities were approximately 3 times more acceptable.

This study harkens the age-old philosophical question: does the end justify the means? Judging by the results, it appears that Americans on both sides of the political spectrum feel that it does, at least to a degree. Democrats and Republicans alike are willing to allow for some shady tactics, provided those tactics advance their own ideals.

Politicians are in a bit of a bind. On the one hand, they are expected to uphold high ethical standards, while on the other hand, they are supposed to represent their voters. If voters hold a double standard for the ethical conduct of their own candidate and the opposing candidate, the overall standard of ethics is likely to fall to the lowest common denominator.

If politicians do get a bit “slimy,” are they the only ones to blame? Who are politicians accountable to, if not their voters? Finally, if the ethical bar is steadily lowered in the service of advancing party agendas, then who is responsible for raising it?

July 28, 2012

I ______ a dollar?

As part of the PoorQuality: Inequality exhibition that is currently on display at the CAH, we are showing a piece of art by Jody Servon entitled “I ______ a dollar.” This piece started out as one hundred $1 bills stuck flat against the wall. The bills hung there in a simple, uniform shape, Washington after Washington. The money was there for the taking, but only if you needed it. Jody asked viewers to think about the value of a single dollar, to contemplate their “needs” in relation to their “wants.”

Featuring: Cara Ansher. Photographed by: Aline Grüneisen.

“My hope is for people to actively consider whether or not having this single dollar will make a difference in his or her life, or if they feel the dollar is better left for someone else who needs it more. Perhaps the invitation to take free money will eclipse the question of want vs. need.”

A week went by, and one dollar disappeared. Afraid that the piece would dissolve too quickly, one lab member replaced the missing dollar. The art was whole again. More time went by, and another lab member needed change for the vending machine. So she took five singles and left her $5 bill. We treated the piece as if it was our own, moving bills around but preserving its integrity. The wall of money remained, for the most part, intact.

We asked Jody about her expectations for the piece.

“Among the scenarios I considered were one person swiping all of the dollars on the first day, the dollars slowly disappearing one-by-one, someone rearranging the dollars in a different design, or somewhat disappointingly, the piece remaining on the wall untouched.”

But the wall did not remain untouched, and one day it encountered a group of guests who came in on a particularly quiet day and left with most of the money. Sure, we were a little annoyed; our precious wall had been ransacked. But that was its purpose, and we laughed it off. At least we had a good story, right?

Some time later, one of the ransackers returned. This time, the CAH was bustling, full of people and lively conversation. He walked in, saw the commotion, and hesitated for just a moment before telling us that he was hungry. We don’t have any food here, but there are plenty of restaurants down the street, we told him. Of course, he was not asking where he could buy food. We knew that. But none of us jumped up to offer what was left of the money hanging on the wall. It was art, after all.

Here we were, hosting an exhibit on “inequality,” and there was no doubt that this man lay farther down on the distribution of wealth than any of us. And in all of our musings on the exhibit, never did we think that we might find ourselves faced with the perfect case of actual inequality.

Until this moment, we had primarily used and conceived of the wall of bills as a cashier. Yes, we contemplated whether we needed or simply wanted a dollar. But most of us don’t need a dollar. In the end, this experience may be the ultimate experiment of our project. And we stumbled into it unintentionally, or rather, he stumbled into our gallery.

A collaboration between Dan Ariely & Aline Grüneisen

The PoorQuality: Inequality Exhibit will be up until the end of August (and we will see whether there are any dollar bills left).

/______ A DOLLAR?

As part of the PoorQuality: Inequality exhibition that is currently on display at the CAH, we are showing a piece of art by Jody Servon entitled “/______ A DOLLAR.” This piece started out as one hundred $1 bills stuck flat against the wall. The bills hung there in a simple, uniform shape, Washington after Washington. The money was there for the taking, but only if you needed it. Jody asked viewers to think about the value of a single dollar, to contemplate their “needs” in relation to their “wants.”

Featuring: Cara Ansher. Photographed by: Aline Grüneisen.

“My hope is for people to actively consider whether or not having this single dollar will make a difference in his or her life, or if they feel the dollar is better left for someone else who needs it more. Perhaps the invitation to take free money will eclipse the question of want vs. need.”

A week went by, and one dollar disappeared. Afraid that the piece would dissolve too quickly, one lab member replaced the missing dollar. The art was whole again. More time went by, and another lab member needed change for the vending machine. So she took five singles and left her $5 bill. We treated the piece as if it was our own, moving bills around but preserving its integrity. The wall of money remained, for the most part, intact.

We asked Jody about her expectations for the piece.

“Among the scenarios I considered were one person swiping all of the dollars on the first day, the dollars slowly disappearing one-by-one, someone rearranging the dollars in a different design, or somewhat disappointingly, the piece remaining on the wall untouched.”

But the wall did not remain untouched, and one day it encountered a group of guests who came in on a particularly quiet day and left with most of the money. Sure, we were a little annoyed; our precious wall had been ransacked. But that was its purpose, and we laughed it off. At least we had a good story, right?

Some time later, one of the ransackers returned. This time, the CAH was bustling, full of people and lively conversation. He walked in, saw the commotion, and hesitated for just a moment before telling us that he was hungry. We don’t have any food here, but there are plenty of restaurants down the street, we told him. Of course, he was not asking where he could buy food. We knew that. But none of us jumped up to offer what was left of the money hanging on the wall. It was art, after all.

Here we were, hosting an exhibit on “inequality,” and there was no doubt that this man lied farther down on the distribution of wealth than any of us. And in all of our musings on the exhibit, never did we think that we might find ourselves faced with the perfect case of actual inequality.

Until this moment, we had primarily used and conceived of the wall of bills as a cashier. Yes, we contemplated whether we needed or simply wanted a dollar. But most of us don’t need a dollar. In the end, this experience may be the ultimate experiment of our project. And we stumbled into it unintentionally, or rather, he stumbled into our gallery.

A collaboration between Dan Ariely & Aline Grüneisen

The PoorQuality: Inequality Exhibit will be up until the end of August (and we will see whether there are any dollar bills left).

July 25, 2012

A Couple Questions

Excuses. Justifications. Rationalizations. Stories. Stretching the truth… So many ways to whitewash the lies we tell ourselves and others. Here are a few questions that might remind you of your own dalliances with dishonesty.

1. What did you say the last time you were running late?

2. Take a look at your desk at home. How many pens and paperclips and so on did you “borrow” from work?

3. How accurate is your online dating profile? How accurate do you think others are?

4. Which e-mail threads would you delete if you knew someone was going to access your e-mail account?

5. Last time someone called you out for misrepresenting something, how did you explain it?

6. What questionable things have you done because “everybody else is doing it?”

7. Which line items on your resume are a bit of stretch?

8. What did you say the last time someone asked how much you weigh?

9. If you opened your mailbox and found a letter from the IRS informing you of an audit, how concerned would you be?

10. Have you ever told someone you never got their voicemail, text, or email?

11. What did you say the last time someone you don’t particularly like asked if you wanted to go to dinner or an event?

12. Speaking of dinner, have you ever said you enjoyed dinner at someone’s house when you didn’t?

13. What do you say when your dentist asks how often you floss?

14. How many haircuts have you claimed to like in the last year? How many did you actually like?

15. What should you be doing instead of reading this blog and answering these questions?

July 24, 2012

A new biweekly Q&A column for the WSJ

I’m going to start taking questions from you, dear readers, deeply ponder them, and send you my responses every other week in the Wall Street Journal.

Read this week’s column, A Double Dip for Voting?, right here. On voting, working, and new experiences.

If you have an interesting question for the column, please email me at: AskAriely@wsj.com

July 19, 2012

Power and Moral Hypocrisy

When a certain former New York State Attorney General became New York Governor, he pledged to “change the ethics of Albany” and make “ethics and integrity the hallmarks of [his] administration.” Sure enough, he went on to fight collar crime and corruption, reduce pollution and prosecute a couple prostitution rings. Oh, but then the New York Times disclosed that this same law-and-order Governor was patronizing high-priced prostitutes. So much for changing the ethics of Albany.

Power and moral hypocrisy are not strangers – it’s one of the oldest stories around (generally going under the name of hubris), and we see it all the time. But why?

A few social scientists decided to take a stab at finding an answer. Joris Lammers and Diederik A. Stapel (from Tilburg University) and Adam D. Galinsky (from Northwestern University) ran five experiments addressing how morality differs among the powerless and powerful.

They simulated a bureaucratic organization and randomly assigned participants to be in a high-power role (prime-minister) or low-power role (civil servant). The prime-minister could control and direct the civil servants. Next, the researchers presented all participants with a seemingly unrelated moral dilemma from among the following: failure to declare all wages on a tax form, violation of traffic rules, and possession of a stolen bike. In each case, participants used a 9-point scale (1: completely unacceptable, 9: fully acceptable) to rate the acceptability of the act. However, half of the participants rated how acceptable it would be if they themselves engaged in the act, while the other half rated how acceptable it would be if others engaged in it.

The researchers found that compared to participants without power, powerful participants were stricter in judging others’ moral transgressions but more lenient in judging their own: “power increases hypocrisy, meaning that the powerful show a greater discrepancy between what they practice and what they preach.”

Joris and Adam hypothesized that this power-hypocrisy connection was due to the sense of entitlement that comes with positions of power. But what if you took away that entitlement by having participants view their power as illegitimate? In that case, the researchers posited, you would see the power-hypocrisy effect disappear.

To test their idea, they had 105 Dutch students write about an experience in which they were powerful or powerless. But half of the participants were asked to write about a time when they deserved their high or low power (it was legitimate), while the other half were asked to write about a time when they didn’t deserve their high or low power. They then had to rate the acceptability of the bike dilemma from above.

Results: when power (or lack thereof) was legitimate, the powerful also exhibited moral hypocrisy (being less moral themselves but judging others more harshly), while the powerless weren’t – just as before. But when power (or lack thereof) was illegitimate, the powerful didn’t show hypocrisy. In fact, the moral hypocrisy effect not only disappeared but was reversed, with the illegitimately powerful becoming stricter in judging their own behavior and more lenient in judging the others.

July 17, 2012

Plagiarism and Essay Mills

Sometimes as I decide what kind of papers to assign to my students, I can’t help but think about their potential to use essay mills.

Essay mills are companies whose sole purpose is to generate essays for high school and college students (in exchange for a fee, of course). Sure, essay mills claim that the papers are meant just to help the students write their own original papers, but with names such as echeat.com, it’s pretty clear what their real purpose is.

Professors in general are very worried about essay mills and their impact on learning, but not knowing exactly what essay mills are or the quality of their output, it is hard to know how worried we should be. So together with Aline Grüneisen, I decided to check it out. We ordered a typical college term paper from four different essay mills, and as the topic of the paper we chose… (surprise!) Cheating.

Here is the description of the task that we gave the four essay mills:

“When and why do people cheat? Consider the social circumstances involved in dishonesty, and provide a thoughtful response to the topic of cheating. Address various forms of cheating (personal, at work, etc.) and how each of these can be rationalized by a social culture of cheating.”

We requested a term paper for a university level social psychology class, 12 pages long, using 15 sources (cited and referenced in a bibliography), APA style, to be completed in the next 2 weeks, which we felt was a pretty basic and conventional request. The essay mills charged us in advance, between $150 to $216 per paper.

Two weeks later, what we received what would best be described as gibberish. A few of the papers attempt to mimic APA style, but none achieve it without glaring errors. Citations were sloppy, and the reference lists abominable – including outdated and unknown sources, many of which were online news stories, editorial posts or blogs, and some that were simply broken links. In terms of the quality of the writing itself, the authors of all four papers seemed to have a very tenuous grasp of the English language, or even how to format an essay. Paragraphs jumped bluntly from one topic to another, and often fell into the form of a list, counting off various forms of cheating or providing a long stream of examples that were never explained or connected to the “thesis” of the paper. Here are some excerpts from the four papers:

“Cheating by healers. Healing is different. There is harmless healing, when healers-cheaters and wizards offer omens, lapels, damage to withdraw, the husband-wife back and stuff. We read in the newspaper and just smile. But these days fewer people believe in wizards.”

“If the large allowance of study undertook on scholar betraying is any suggestion of academia and professors’ powerful yearn to decrease scholar betraying, it appeared expected these mind-set would component into the creation of their school room guidelines.”

“By trusting blindfold only in stable love, loyalty, responsibility and honesty the partners assimilate with the credulous and naïve persons of the past.“

“Women have a much greater necessity to feel special.”

“The future generation must learn for historical mistakes and develop the sense of pride and responsibility for its actions.”

At this point we were rather relieved, figuring that the day is not here where students can submit papers from essay mills and get good grades for them. Moreover, we concluded that if students did try to buy a paper from an essay mill, just like us, they would feel that they have wasted their money and won’t try it again.

But the story does not end here. We submitted the four essays to WriteCheck.com, a website that inspects papers for plagiarism and found that two of the papers were 35-39% copied from existing works. We decided to take action with the two largely plagiarized papers, and contacted the essay mills requesting our money back. Despite the solid proof that we provided, the companies insisted that they did not plagiarize. One company even tried to threaten us by saying that they will get in touch with the dean at Duke to alert them to the fact that we submitted work that is not ours (just imagine being a student who had used the paper for a class!).

The bottom line? I think that the technological revolution has not yet solved students’ problems. They still have no other option but to actually work on their papers (or maybe cheat the old fashioned way and copy from friends). But I do worry about the existence of essay mills and the signal that they send to our students. As for our refund, we are still waiting…

Dan Ariely's Blog

- Dan Ariely's profile

- 3932 followers