Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 19

February 1, 2013

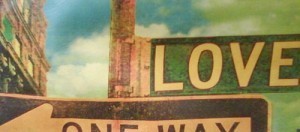

Love From God, Love For Neighbor

My friend, Jono Linebaugh, and I sat down recently to talk about what love looks like horizontally and how it actually happens.

Love for Neighbor | Jono Linebaugh and Tullian Tchividjian from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

January 28, 2013

Freedom Is Serious Business

A golden word from Robert Capon–a word that the church must heed:

If we are ever to enter fully into the glorious liberty of the children of God, we are going to have to spend more time thinking about freedom than we do. The church, by and large, has had a poor record of encouraging freedom. It has spent so much time inculcating in us the fear of making mistakes that it has made us like ill-taught piano students: we play our pieces, but we never really hear them because our main concern is not to make music but to avoid some flub that will get us in trouble. The church, having put itself in loco parentis (in the place of a parent), has been so afraid we will lose sight of the need to do it right that it has made us care more about how we look than about who Jesus is–made us act more like subjects of a police state than fellow citizens of the saints.

January 25, 2013

The Burned Over Place

One of the best books I’ve read in years is a short book originally published in 1983 by Paul Zahl entitled Who Will Deliver Us? The Present Power of the Death of Christ. Dr. Zahl plumbs the depths of the Gospel for everyday life in a paradigm shifting way.

One of the best books I’ve read in years is a short book originally published in 1983 by Paul Zahl entitled Who Will Deliver Us? The Present Power of the Death of Christ. Dr. Zahl plumbs the depths of the Gospel for everyday life in a paradigm shifting way.

Of the book, J.I. Packer writes:

Zahl knows the authentic gospel and the 20th Century human heart and probes deeply into both.

And John Stott wrote:

A brave and honest book. An unusual combination of pastoral compassion and theological integrity.

His grasp of the demands of God’s Law and the deliverance of God’s Gospel is both deep and wide. But what makes this book a cut above the rest is Zahl’s ability to connect the Law and the Gospel to our everyday fears, expectations, relationships, shattered dreams, and insecurities.

Speaking of Law and Gospel, Zahl paints a vivid picture that reveals our helplessness before the devastation and comprehensiveness of Divine expectation and how that helplessness creates the space for God’s amazing grace and the freedom it produces:

I’m a little like the duck hunter who was hunting with his friend in a wide-open barren of land in southeastern Georgia. Far away on the horizon he noticed a cloud of smoke. Soon, he could hear the sound of crackling. A wind came up and he realized the terrible truth: a brush-fire was advancing his way. It was moving so fast that he and his friend could not outrun it. The hunter began to rifle through his pockets. Then he emptied all the contents of his knapsack. He soon found what he was looking for-a book of matches. To his friend’s amazement, he pulled out a match and struck it. He lit a small fire around the two of them. Soon they were standing in a circle of blackened earth, waiting for the brush fire to come. They did not have to wait long. They covered their mouths with their handkerchiefs and braced themselves. The fire came near-and swept over them. But they were completely unhurt. They weren’t even touched. Fire would not burn the place where fire had already burned.

The law is like the brush-fire. I cannot escape it. But if I stand in the burned-over place, where law has already burned its way through, then I will not get hurt. Not a hair of my head will be singed. The death of Christ is the burned-over place. There I huddle, hardly believing yet relieved. Christ’s death has disarmed the law. “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

Who Will Deliver Us? The Present Power of the Death of Christ (pg. 42-43)

January 21, 2013

Presumption Produces Self-Deception

“For if anyone thinks he is something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.” (Galatians 6:3)

“For if anyone thinks he is something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.” (Galatians 6:3)

I’ve made the point before that regardless of how well I think I’m doing in the sanctification project or how much progress I think I’ve made since I first became a Christian, like Paul in Romans 7, when God’s perfect law becomes the standard and not “how much I’ve improved over the years”, I realize that I’m a lot worse than I fancy myself to be. Whatever I think my greatest vice is, God’s law shows me that my situation is much worse: if I think it’s anger, the law shows me that it’s actually murder; if I think it’s lust, the law shows me that it’s actually adultery; if I think it’s impatience, the law shows me that it’s actually idolatry (read Matthew 5:17-48). God’s law is like a mirror: it shows us who we really are and what we really need.

We’ll always maintain a posture of suspicion regarding the radicality and hilarity of unconditional grace as long as we think we’re basically OK. Our presumption of “okayness” leads to a self-deception that robs us of the joy of our salvation and the undomesticated freedom that Christ paid so dearly to secure for sinners like me.

Martin Luther shows how probing the problem of presumption is and reveals that our so-called progress may not be as impressive as we think it is:

Presumption follows when a man sets himself to fulfill the Law with works and diligently sees to it that he does what the letter of the Law asks him to do. He serves God, does not swear, honors father and mother, does not kill, does not commit adultery, and the like. Meanwhile, however, he does not observe his heart, does not note the reason why he is leading such a good life. He does not see that he is merely covering the old hypocrite in his heart with such a beautiful life. For, if he looked at himself aright-at his own heart-he would discover that he is doing all these things with dislike and out of compulsion; that he fears hell or seeks heaven, if not also for more insignificant matters: honor, goods, health; and that he is motivated by the fear of shame or harm or diseases. In short, he would have to confess that he would rather lead a different life if the consequence of such a life did not deter him; for he would not do it merely for the sake of the Law. But because he does not see this bad reason, he lives on in security, looks only at the works, not into the heart, and so assumes that he is keeping the Law of God well. (Luther’s Works, St. Louis edition, 11:81 ff)

The Heidelberg Catechism also puts things in perspective:

Question 62: But why cannot our good works be the whole, or part, of our righteousness before God?

Answer: Because, the righteousness which can be approved of before the tribunal of God, must be absolutely perfect, and in all respects conformable to the divine law; and also, that our best works in this life are all imperfect and defiled with sin.

“At the cross”, says Gerhard Forde, “God stormed the last bastion of the self, the last presumption that you were going to do something for him.” Genuine freedom awaits all who stop trusting in their own work and start trusting in Christ’s work.

January 17, 2013

Free To Be Fallen

Covenant Theological Seminary sat down with me recently to talk about my book Glorious Ruin: How Suffering Sets You Free.

Their specific question was, “How can church leaders cultivate a safe place to talk about suffering?” I hope this short video will be both helpful and comforting to you.

January 14, 2013

Time To Stop Looking In And Start Looking Up

A shift has taken place in the Evangelical church with regard to the way we think about the gospel and it’s far from simply an ivory tower conversation. This shift effects us on the ground of everyday life.

A shift has taken place in the Evangelical church with regard to the way we think about the gospel and it’s far from simply an ivory tower conversation. This shift effects us on the ground of everyday life.

In his book Paul: An Outline of His Theology, famed Dutch Theologian Herman Ridderbos (1909 – 2007) summarizes this shift which took place following Calvin and Luther. It was a sizable but subtle shift which turned the focus of salvation from Christ’s external accomplishment to our internal appropriation:

While in Calvin and Luther all the emphasis fell on the redemptive event that took place with Christ’s death and resurrection, later under the influence of pietism, mysticism and moralism, the emphasis shifted to the individual appropriation of the salvation given in Christ and to it’s mystical and moral effect in the life of the believer. Accordingly, in the history of the interpretation of the epistles of Paul the center of gravity shifted more and more from the forensic to the pneumatic and ethical aspects of his preaching, and there arose an entirely different conception of the structures that lay at the foundation of Paul’s preaching.

Donald Bloesch made a similar observation when he wrote, “Among the Evangelicals, it is not the justification of the ungodly (which formed the basic motif in the Reformation) but the sanctification of the righteous that is given the most attention.”

With this shift came a renewed focus on the internal life of the individual. The subjective question, “How am I doing?” became a more dominant feature than the objective question, “What did Jesus do?” As a result, generations of Christians were taught that Christianity was primarily a life-style; that the essence of our faith centered on “how to live”; that real Christianity was demonstrated foremost in the moral change that took place inside those who had a “personal relationship with Jesus.” Our ongoing performance for Jesus, therefore, not Jesus’ finished performance for us, became the focus of sermons, books, and conferences. What I need to do and who I need to become, became the end game.

To be sure, the Bible has plenty to say about our becoming like Jesus. But our transformation is a secondary theme. The primary theme of the Bible is Christ’s substitution–the fact that Jesus became like us. The modern church has sadly reversed the order. The focus of the Christian faith has become the life of the Christian.

Believe it or not, this shift in focus from “the forensic to the pneumatic”, from the external to the internal, has enslaving practical consequences.

When you’re on the brink of despair-looking into the abyss of darkness, experiencing a dark-night of the soul–turning to the internal quality of your faith will bring you no hope, no rescue, no relief. Too often our preaching (and our counseling) is the equivalent of giving a drowning man swimming lessons: “Paddle harder, kick faster.” We assume that people possess the internal power to get things right so we turn them in to themselves. But, as too many people already know, every internal answer will collapse underneath you. Turning to the external object of your faith, namely Christ and his finished work on your behalf, is the only place to find peace, re-orientation, and help. The gospel always directs you to something, Someone, outside you instead of to something inside you for the assurance you crave and need in seasons of desperation and doubt. The surety you long for when everything seems to be falling apart won’t come from discovering the dedicated “hero within” but only from the realization that no matter how you feel or what you’re going through, you’ve already been discovered by the “Hero without.”

As Sinclair Ferguson writes in his book The Christian Life:

True faith takes its character and quality from its object and not from itself. Faith gets a man out of himself and into Christ. Its strength therefore depends on the character of Christ. Even those of us who have weak faith have the same strong Christ as others!

By his Spirit, Christ’s continuing subjective work in me consists of his constant, daily driving me back to his completed objective work for me. Sanctification feeds on justification, not the other way around. The gospel is the good news announcing Christ’s infallible devotion to us in spite of our lack of devotion to him. The gospel is not a command to hang onto Jesus. Rather, it’s a promise that no matter how weak your faith may be in seasons of spiritual depression, God is always holding on to you.

Martin Luther had a term for the debilitating danger that comes from locating our hope in anything inside us: monstrum incertitudinis (the monster of uncertainty). It’s a danger that has always plagued Christians since the fall but especially Christians in our highly subjectivistic age. And it’s a monster that can only be destroyed by the external promises of God in Jesus.

Romans 5:1 says, “Therefore, since we have been justified by faith we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.” This is a bonafide peace that’s built on a real change in status before God—from standing guilty before God the judge to standing righteous before God our Father. This is the objective custody of even the weakest believer. It’s a peace that rests squarely on the fact that we’ve already been “reconciled to God by the death of his Son” (v. 10), justified before God once and for all through faith in Christ’s finished work. It will surely produce real feelings and robust action, but this peace with God that Paul describes rests securely on the work of Christ for us, outside us. The truth is, that the more I look into my own heart for peace, the less I find. On the other hand, the more I look to Christ and his promises for peace, the more I find.

Romans 5:1 says, “Therefore, since we have been justified by faith we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.” This is a bonafide peace that’s built on a real change in status before God—from standing guilty before God the judge to standing righteous before God our Father. This is the objective custody of even the weakest believer. It’s a peace that rests squarely on the fact that we’ve already been “reconciled to God by the death of his Son” (v. 10), justified before God once and for all through faith in Christ’s finished work. It will surely produce real feelings and robust action, but this peace with God that Paul describes rests securely on the work of Christ for us, outside us. The truth is, that the more I look into my own heart for peace, the less I find. On the other hand, the more I look to Christ and his promises for peace, the more I find.

So, when pressed in on every side, look up. In God’s economy, the only way out is always up, not in.

January 9, 2013

The Gift

Mike Horton and the boys over at The White Horse Inn have been feeding me 200 proof gospel for quite some time. In a blog post two years ago, they linked to a sermon that Dr. Rod Rosenbladt preached which featured a fictional dialogue between God and a sinner–a sermon which will make the pious quite uncomfortable. They introduced the sermon with these words:

Mike Horton and the boys over at The White Horse Inn have been feeding me 200 proof gospel for quite some time. In a blog post two years ago, they linked to a sermon that Dr. Rod Rosenbladt preached which featured a fictional dialogue between God and a sinner–a sermon which will make the pious quite uncomfortable. They introduced the sermon with these words:

How do we come to faith in Christ? How is that faith sustained and grown? How are we able to have a desire for Christ and to worship and glorify Him?

They’re relatively simple questions, but the correct answer is a tough one for sinners. It is tough because we sinners get no credit whatsoever. We receive our faith and its benefits—including the maintenance of our faith and any outward signs—purely as God’s gracious gift.

But we sinners don’t like that. The old Adam in us wants credit for something in regards to his faith and works. We much prefer to think that even if God comes most of the way to help us, that we are still “keeping our end of the bargain” in some way, as though we could in any way do even one single instance of it without God’s gifts.

The truth is that we don’t get credit for any part of our faith and Christian lives; just as the dry bones spoken to in the Desert valley get no credit for rising up and getting flesh back on their skeletons; just as Lazarus got no credit for rising from the dead. That’s tough for sinners to swallow. So the old Adam in us works like crazy to find something…anything for which he can get some kind of credit.

We only bring one thing to the bargaining table in the courtroom of judgment: sin. The trouble is, Christ Himself makes clear that the law demands that we “be perfect, as our heavenly Father is perfect.” Sin once and it’s over. You can’t be “even-more-than-perfect” to erase the sin and then go back to being plain ol’ perfect again.

We only bring one thing to the bargaining table in the courtroom of judgment: sin. The trouble is, Christ Himself makes clear that the law demands that we “be perfect, as our heavenly Father is perfect.” Sin once and it’s over. You can’t be “even-more-than-perfect” to erase the sin and then go back to being plain ol’ perfect again.

Dr. Rosenbladt tackles some of this in a sermon he once gave for Reformation Day, entitled, “Gift?”. It is a simple discussion between a sinner and God. But he minces no words when it comes to revealing exactly how much desire for God there is in the sinner’s heart. That is: none.

Dr. Rosenbladt offers this caveat regarding this sermon: “Don’t let anybody tell you I don’t hold to Sola Scriptura. This is strictly a literary device, no more!” Below is an excerpt.

God: I told you. I hate religion. Religion was your idea – not Mine. You have forgotten what Anselm said: “You have not yet considered the depth of your sin.”

Sinner: But I want to show you I have. I really have. I know it is really deep. Talk to me. Teach me sanctification.

God: I told you. You aren’t ready for sanctification yet. You just imagine that you are ready. You are arrogant and you don’t know it.

Sinner: What do you mean? I am ready.

God: You are not. If you were, you wouldn’t be talking like you are talking.

Sinner: Well, what then?

God: Just sit there. Sit there for a long while.

Sinner: And do what?

God: Consider the shed blood. Consider that the blood was enough. Think about the fact that it isn’t your repenting that has saved you. Think about the fact that it isn’t your faith that is saving you.

Sinner: Can’t I just, as you said, just think about my sin and the depth of it?

God: That is a start. But you like doing that. You like it too much.

Sinner: This makes no sense. What are you saying?

God: I am saying that you like atoning for yourself by feeling guilty. And you like atoning for yourself by thinking about your faith.

Sinner: Well, what else is there?

God: There is Jesus Christ – but you don’t consider Him. You are not used to gifts. You don’t think much about them. Gifts make you nervous and tense. You don’t know what to do, so you jump to trying to impress Me. I am not impressible.

You can read the entire sermon at New Reformation Press.

January 5, 2013

A Hymn To God The Father

The hymn below by English poet and cleric John Donne (1572-1631) says it all: God meets my ongoing sin with his inexhaustible forgiveness. 70 times 7.

The hymn below by English poet and cleric John Donne (1572-1631) says it all: God meets my ongoing sin with his inexhaustible forgiveness. 70 times 7.

My friend Shane Rosenthal sent me a note explaining that, according to some commentators, there is double meaning in the line, “Thou hast done” which repeats throughout the poem. It obviously refers to that which God has done for Donne in contrast to that which Donne has done (and continues to do). But the other meaning, especially clear in the last stanza, is a play on the poet’s own name: “Thou hast Donne.” It is his realization that despite his weak grip on God, God’s grip on him is perfect and forever, that finally ends his fears.

It never ceases to amaze me that, if you are in Christ, you can never, ever, ever outsin the coverage of God’s forgiveness. Amazing love…how can it be?

WILT Thou forgive that sin where I begun,

Which was my sin, though it were done before?

Wilt Thou forgive that sin, through which I run,

And do run still, though still I do deplore?

When Thou hast done, Thou hast not done,

For I have more.

Wilt Thou forgive that sin which I have won

Others to sin, and made my sin their door?

Wilt Thou forgive that sin which I did shun

A year or two, but wallowed in a score?

When Thou hast done, Thou hast not done,

For I have more.

I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

My last thread, I shall perish on the shore ;

But swear by Thyself, that at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

And having done that, Thou hast Donne ;

I fear no more.

January 1, 2013

On To The Next One…

Today is the very first day of a brand new year. And for many that means a fresh start.

Today is the very first day of a brand new year. And for many that means a fresh start.

This is the year. It all starts now. We resolve to turn over a new leaf–and this time we’re serious. This time we’re really going to try, we’re not going to quit. We promise ourselves that we’re going to quit bad habits and start good ones. We’re going to get in shape, eat better, lust less, waste less time, be more content, more disciplined, more intentional. We’re going to be better husbands, wives, fathers, mothers. We’re going to pray more, serve more, plan more, give more, read more, and memorize more Bible verses. We’re going to finally be all that we can be. No more messing around.

Well…I say try. Seriously, try. You might make some great strides this year. I’m hoping to. There are a lot of improvements I’m hoping to make over the next 12 months. But don’t be surprised a year from now when you realize that you’ve fallen short…again.

For those who try and try, year after year, again and again, to get better and better, only to take three steps forward then two steps back, one step forward then three steps back…I have good news for you: you’re in good company!

My friend Jean Larroux sent me this powerful illustration that he got from Jack Miller.

Miller recounts the valiant efforts of Samuel Johnson (a literary giant of the 18th century) to fight sloth and to get up early in the morning to pray. Taken from Johnson’s diary and prayer journal, Jack gives us a record–through the years–of Johnson’s life-long resolutions, failures, and frustrations:

1738: He wrote, “Oh Lord, enable me to redeem the time which I have spent in sloth.”

1757: (19 years later) “Oh mighty God, enable me to shake off sloth and redeem the time misspent in idleness and sin by diligent application of the days yet remaining.”

1759: (2 years later) “Enable me to shake off idleness and sloth.”

1761: “I have resolved until I have resolved that I am afraid to resolve again.”

1764: “My indolence since my last reception of the sacrament has sunk into grossest sluggishness. My purpose is from this time to avoid idleness and to rise early.”

1764: (5 months later) He resolves to rise early, “not later than 6 if I can.”

1765: “I purpose to rise at 8 because, though, I shall not rise early it will be much earlier than I now rise for I often lie until 2.”

1769: “I am not yet in a state to form any resolutions. I purpose and hope to rise early in the morning, by 8, and by degrees, at 6.”

1775: “When I look back upon resolution of improvement and amendments which have, year after year, been made and broken, why do I yet try to resolve again? I try because reformation is necessary and despair is criminal.” He resolves again to rise at 8.

1781: (3 years before his death) “I will not despair, help me, help me, oh my God.” He resolves to rise at 8 or sooner to avoid idleness.

I love the never-quit effort of Johnson. What he chronicles sounds so much like me over the years. Try and fail. Fail then try. Try and succeed. Succeed then fail. Two steps forward. One step back. One step forward. Three steps back. Every year I get better at some things, worse at others. For example, this past year I’ve become a lot slower to “make my point” in conversations with my wife–I listen more and talk less (one step forward). I let things go more quickly, criticism doesn’t cripple me as much, and I’m actually becoming more patient with people–I’m trusting God more (cha-ching, cha-ching). But, due to some relationally painful situations this past year, I’ve also become more closed off to people in order to protect myself (one step back). More than ever, I’ve tended toward relational distance–I trust people less (gong! gong!).

I love the never-quit effort of Johnson. What he chronicles sounds so much like me over the years. Try and fail. Fail then try. Try and succeed. Succeed then fail. Two steps forward. One step back. One step forward. Three steps back. Every year I get better at some things, worse at others. For example, this past year I’ve become a lot slower to “make my point” in conversations with my wife–I listen more and talk less (one step forward). I let things go more quickly, criticism doesn’t cripple me as much, and I’m actually becoming more patient with people–I’m trusting God more (cha-ching, cha-ching). But, due to some relationally painful situations this past year, I’ve also become more closed off to people in order to protect myself (one step back). More than ever, I’ve tended toward relational distance–I trust people less (gong! gong!).

To complicate matters even more, when I honestly acknowledge the ways I’ve gotten worse, it’s actually a sign that I may be getting better. And when I become proud of the ways I’ve gotten better, it’s actually a sign that I’ve gotten worse. And round and round we go. Furthermore, no matter how hard I try, I still get frustrated by the same things that frustrated me 20 years ago: traffic jams, unexpected interruptions, long lines, feeling misunderstood, people who “play it safe”, and so on and so forth. You get the idea. In some ways we get better. In some ways we get worse. And in other ways we basically stay the same.

What I’m most deeply grateful for (as was Johnson) is that God’s love for me, approval of me, and commitment to me does not ride on my resolve but on Jesus’ resolve for me. The gospel is the good news announcing Jesus’ infallible devotion to us in spite of our inconsistent devotion to him. The gospel is not a command to hang onto Jesus. Rather, it’s a promise that no matter how weak and unsuccessful your faith and efforts may be, God is always holding on to you. The glory of a new year (and of every year) is the chronicling of God’s successes perfectly meeting my failures.

It’s ironically comforting to me as this new year gets under way that I am weak and He is strong–that while my love for Jesus will continue to fall short, Jesus’ love for me will never fall short. For, as Mark Twain said, “Heaven goes by favor. If it went by merit, your dog would get in and you would stay out.”

Thank God!

Happy New Year!

December 26, 2012

Give Me Law Or Give Me Death!

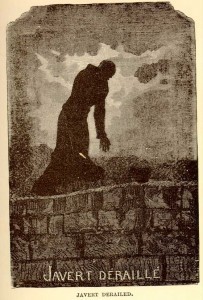

Last night we went to see Les Miserables. As has already been discussed here and written about here, the contrast between law and grace is both pronounced and profound.

Last night we went to see Les Miserables. As has already been discussed here and written about here, the contrast between law and grace is both pronounced and profound.

For me, the most powerful scene in the movie is Inspector Javert’s song right before he kills himself.

Javert embodies our natural addiction to law and our natural aversion to grace. Committed to the rigorous inflexibility of the law, Javert has been given grace time and time again from the very one he has mercilessly hunted for decades, Jean Valjean. The grace of Valjean haunts and radically disorients Javert.

Javert sings:

Who is this man? What sort of devil is he, to have me caught in a trap and choose to let me go free? It was his hour at last to put the seal on my fate, wipe out the past and wash me clean off the slate! All it would take was a flick of his knife. Vengeance was his and he gave me back my life! Damned if I’ll live in the debt of a thief! Damned if I’ll yield at the end of the chase! I am the Law and the Law is not mocked. I’ll spit his pity right back in his face! There is nothing on Earth that we share! It is either Valjean or Javert!

How can I now allow this man to hold dominion over me? This desperate man whom I have hunted…He gave me my life. He gave me freedom. I should have perished by his hand. It was his right. It was my right to die as well. Instead I live…but live in Hell! And my thoughts fly apart. Can this man be believed? Shall his sins be forgiven? Shall his crimes be reprieved? And must I now begin to doubt, who never doubted all these years? My heart is stone, and still it trembles! The world I have known is lost in shadow. Is he from heaven or from hell? And does he know…that, granting me my life today, this man has killed me, even so? I am reaching…but I fall. And the stars are black and cold, as I stare into the void of a world that cannot hold. I’ll escape now from that world, from the world of Jean Valjean. There is nowhere I can turn, there is no way to go on!

Javert concludes that he would rather die than deal with the disorienting reality of grace…and so he jumps. He chooses death over grace, control over chaos.

For Javert (as with all of us), the logic of law makes sense. We love the “if/then” proposition: “If” you do this, “then” I will do that. We love “what-goes-around-comes-around” conditionality. It makes us feel safe. It’s easy to comprehend. It makes perfect sense to our grace-shy hearts. It’s makes life formulaic. It breeds a sense of manageability. And best of all, it keeps us in control. We get to keep our ledgers and scorecards.

The logic of grace, on the other hand, is incomprehensible to our law-locked hearts. Grace is thickly counter-intuitive. It feels risky and unfair. It’s dangerous and disorderly. It wrestles control out of our hands. It is wild and unsettling. It turns everything that makes sense to us upside-down and inside-out. Law says, “Good people get good stuff; bad people get bad stuff.” Grace says, “The bad get the best; the worst inherit the wealth; the slave becomes a son.” This offends our deepest sense of justice and rightness. We are, by nature, allergic to grace.

As I was watching that scene last night, I couldn’t help but think of the many inside the church who, like Javert, have no idea what to do with the disorientating unconditionality of grace and reflexively fight it at every turn and in every way without even realizing what they are fighting or why.

We are so deeply conditioned against grace because we’ve been told in a thousand different ways that accomplishment precedes approval. So, when we hear, “Of course you don’t deserve it, but I’m giving it to you anyway,” we wonder, “What is this really about? What’s the catch?” Internal bells and alarms start to go off, and we begin saying “wait a minute…this sounds too good to be true.” By nature we’re all wary of grace. We wonder about the ulterior motives of the excessively generous. What’s in it for him? After all, who could trust in or believe something so radically unbelievable?

Life the way we’ve always known it to work doesn’t make sense anymore if grace is true.

Robert Capon articulates brilliantly the prayer of the grace-averse heart:

Lord, please restore to us the comfort of merit and demerit. Show us that there is at least something we can do. Tell us that at the end of the day there will at least be one redeeming card of our very own. Lord, if it is not too much to ask, send us to bed with a few shreds of self-respect upon which we can congratulate ourselves. But whatever you do, do not preach grace. Give us something to do, anything; but spare us the indignity of this indiscriminate acceptance.

As I was falling asleep last night and thinking about Javert’s struggle, I couldn’t help but wonder if the church has too often chosen death over grace. Fearful of what kind of chaos would ensue if we abandoned ourselves wholly to the radicality of grace, we cling to control–we stick with what we know so well, with what comes natural.

It is high time, in my opinion, for the church to embrace sola gratia (grace alone) anew. “For many of us the time has come to abandon once and for all our play-it-safe, toe-dabbling Christianity and dive in” (Dane Ortlund). No more “yes grace, but…”. No more fine print. No more conditions, qualifications, and footnotes. And especially, no more silly cries for “balance.” It is time to get drunk on grace. Two hundred-proof, defiant grace.

It’s scandalous and scary, unnatural and undomesticated…but it’s the only thing that can set us free and light the church on fire.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers