Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 23

September 4, 2012

Belovedness Engenders Love

In his book 2000 Years of Amazing Grace: The Story and Meaning of the Christian Faith, Paul Zahl autobiographically recounts what happened to him many years ago when he discovered the indispensability of grace to produce the good works toward our neighbor outlined in the Bible:

My doing of the good deeds [Jesus] taught actually hinged on Him saving me–I, who had found myself paralyzed and blocked from doing those good deeds.When I felt myself loved in my chains, in my paralyses, that feeling of being loved seemed to trigger the very motivation and strength that had failed me before. Being treated forgivingly in my faults and fears freed me up. The faults themselves lost some of their binding strength. The confining fears ceased to restrict so tightly. There was an empowering connection between Jesus’ saving me (who he was for me) and the fuel to do what he said I should do (what he taught).

I take this connection between saving and the response to being saved that results in morally good actions (loving service to our neighbor), to be the heart of Christianity. It is the relation of being loved to loving. Being loved creates an environment inside a person by which the works of love begin to take place naturally. Loving is born from being loved…”Love to the loveless shown, that they might lovelier be” is a seventeenth-century way of saying it.

As I’ve said on numerous occasions here, the motivation and fuel to do good (which the Bible always describes horizontally in terms of loving service to others) comes from being moved by the completed work of Jesus for us. The impulsion to “do” comes only out of this undomesticated declaration that everything has already been done. Those who obey more are those who increasingly “get” that their standing with God is not based on their imperfect obedience to Jesus, but Jesus’ perfect obedience for them. The secret of grace is that we actually perform better as we grow to understand that God’s love for us is based on Christ’s performance, not our performance.

Another way to put this is to affirm that grace, not law, produces love–the love for God and neighbor that Jesus teaches (Luke 10:27). His love for us begets love from us.

August 31, 2012

Minimizing Suffering Minimizes The Cross

The following is an excerpt from my forthcoming book Glorious Ruin: How Suffering Sets You Free

The following is an excerpt from my forthcoming book Glorious Ruin: How Suffering Sets You Free

It is ironic that one of the most beautiful and encouraging verses in the Bible is also one of the most dangerous. You probably know which one I’m talking about. “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose” (Rom. 8:28).

I’ve witnessed that verse misused more than any other. And I know I have been guilty of misusing it myself. Maybe you’ve heard it thrown out in a small-group setting, maybe in a casual discussion. Inevitably someone has just shared a painful story about what she’s going through or has gone through. We don’t know what to say—the predicament is a sad one. It goes beyond the normal categories and struggles. It’s awkward. We want to help, perhaps, but we also want the moment to end. Or maybe we are just focused on saying the “right” thing, the faithful thing.

Make no mistake, in this context, Romans 8:28 can be a bona fide conversation stopper. A spiritual “shut up,” if you will. And lest we think only Christians are prone to such insensitivity, the secular translation, “Don’t worry; it’ll all work out,” is no less ubiquitous. This is classic minimization of suffering.

Minimization involves any attempt to downplay or reduce the extent and nature of pain. Any rhetorical or spiritual device that underestimates the seriousness of suffering essentially minimizes it. Quick fixes are inevitably minimizing tactics. Platitudes are minimizing tactics. If moralization reduces suffering to a moral or spiritual issue, minimization makes similar reductions. For example, when doctors reduce suffering to a matter of medication or chemistry, or psychologists to one’s dysfunctional upbringing (which is not to say those things can’t be factors). In fact, naturalistic or materialistic outlooks are especially susceptible to minimization.

Whether suffering is approached through the eyes of faith or not, the God of the Bible never reduces or compartmentalizes suffering—ever. The problems of life are large and complex; pat answers are not only inaccurate but also unkind.

In his book Shattered Dreams, Larry Crabb relates the experience of a man who suffered an enormous loss. Crabb describes the man’s friends as concerned and supportive, sending books on handling grief, spending time with him both in prayer and on the golf course, etc. Several friends sent letters expressing their love, and a few included verses from the Bible they said had been impressed on them by the Lord.

When his friends called or came to visit, the first question after a quick greeting was always “How are you doing?” He hated the question the first time he heard it and hated it more each time he heard it again. He knew the “right” answer, the one his friends were hoping to hear, the one that had more to do with relieving their concern than with expressing his own heart. The hoped-for answer could be expressed in many ways, but its message was always the same. “It’s hard, but I’m okay, or at least I’m getting there.” …His words [had] their intended effect. The questioner smiled with relief and said, “I’m really glad. Not surprised though. Lots of us have been praying.” … As the struggling man listened to his friend, he felt a tidal wave of intense loneliness sweep over him. He returned the smile but his soul shriveled behind a familiar wall that left him lifeless, more desperate and alone than before.

As the story illustrates, when the bottom falls out of our lives, we don’t necessarily find it comforting when people try to cheer us up. No matter how well intended, such overtures create pressure that adds to our distress. Not only are we suffering, but we now feel bad about how we make those around us feel or, at least, about the disconnect between where they would like us to be and where we actually are.

All of our attempts (well intentioned as they may be) to minimize suffering reveal our universal, fatal love affair with control and law. If I can just recast suffering in a diminished role, then I will hurt less. Or conversely, if I just do the right thing or just obey enough, God will be pleased, and I will hurt less. Neither approach takes God into much consideration. He is a passive bystander at best in either scenario. And both approaches stand on the premise of you and me possessing power that we simply do not have. Yet the knowledge of our limitations does not stop us from exhausting ourselves—indeed, from destroying ourselves—in our tireless attempts to grab the reins. The breadth of human

impasse is the opposite of minimal. Yet as Paul Zahl wrote:

An old joke is repeated year after year in the graffiti on public buildings. Someone writes for all to see, “Christ is the answer.” After it someone has added, “But what is the question?” The addition is perceptive…. Is there a real problem to which the atonement of Jesus Christ offers a solution? What is irremediable about the human condition that it should require a death for healing to occur? The extreme nature of the solution, one person’s death for the “salvation” of others, presupposes an extreme need on the part of the others.

The cross makes a mockery of our attempts to defend and deliver ourselves. God provided a shocking remedy that both reveals and addresses the depth of our illness, our “sickness unto death.” Indeed, despite our efforts to contain, move past, or silence it, that ol’ rugged cross stands tall, resolutely announcing that “in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.” All things, Paul said, even misused Bible verses and the men and women who misuse them. Instead of diminishing our pain, then, these words proclaim the corresponding and overwhelming gratuity of our Redeemer.

August 27, 2012

Insecurity Produces Pride

If you have the reputation of being somewhat critical, “hard edged”, and defensive–it may reveal much more than you realize. Believe it or not, there is a direct and explicit connection between a lack of confidence in God’s unconditional love for you and your tendency to be critical, assertive, and defensive. When you function as if God’s love and acceptance of you depends on your spiritual achievements, your obedience, and your performance, you develop a “defensive assertion of your own righteousness and defensive criticism of others.”

Big thanks to Tom Wood for highlighting these insightful words from Richard Lovelace:

Christians who are no longer sure that God loves and accepts them in Jesus, apart from their present spiritual achievements, are subconsciously insecure persons–much less secure than non-Christians–because they have too much light to rest easily under the constant bulletins they receive from their Christian environment about the holiness of God and the righteousness they are supposed to have. Their insecurity shows itself in pride, a fierce defensive assertion of their own righteousness and defensive criticism of others. They come naturally to hate other cultural styles and other races in order to bolster their own security and discharge their suppressed anger. They cling desperately to legal, Pharisaical righteousness. But envy, jealousy and other branches on the tree of sin grow out of their fundamental insecurity.

It is often necessary to convince sinners of the grace and love of God toward them, before we can get them to look at their problems. Then the vision of grace and the sense of God’s forgiving acceptance may actually cure most of the problems.

This may account for Paul’s frequent fusing of justification and sanctification.

August 23, 2012

The Pastoral Practicality Of Law-Gospel Theology

Our church was recently hit with a high-ranking moral tragedy. It was discovered that a staff member (and close friend) was engaging in marital infidelity. I was both shocked and saddened. I didn’t see it coming. None of us did. Of all the crises I’ve faced and had to deal with over the last 17 years of pastoral ministry, this was a first for me. I have dealt on numerous occasions with husbands and wives in the throes of an extramarital affair, but never a staff member. Never someone this close to me. It’ll take me a long time to get over this one.

Our church was recently hit with a high-ranking moral tragedy. It was discovered that a staff member (and close friend) was engaging in marital infidelity. I was both shocked and saddened. I didn’t see it coming. None of us did. Of all the crises I’ve faced and had to deal with over the last 17 years of pastoral ministry, this was a first for me. I have dealt on numerous occasions with husbands and wives in the throes of an extramarital affair, but never a staff member. Never someone this close to me. It’ll take me a long time to get over this one.

On top of having to deal with this on a very personal level, I had the weighty responsibility of leading our church through this. How do you handle something like this? What do you tell people? I reached out to a small handful of older, wiser, more seasoned friends of mine who are pastors and counselors that have lived and led through situations like this. Their help and counsel and encouragement and insight were indispensable life savers for me. What would I do without these people in my life?

One week after we discovered the affair, I had to stand up on my first Sunday back from vacation and tell our church what happened. I, of course, did not share much. I steered clear of details. I simply told our church that this man had been engaged in marital infidelity and the situation was such that it required him to be removed from his position. I shared with our church the detailed ways that we were caring for the families involved and communicated our long-term commitment to continue caring for the families involved. It was a tough morning for me. It was a tough morning for everybody. The hurt, the anger, the sadness, the confusion.

I preached from Gal 5:13 that morning, and among the things I emphasized and explained to our church was that we are not a one word community (law or gospel) but a two word community (law then gospel). A law-only community responds to a situation like this by calling for the guy’s head (sadly, many churches are guilty of this). These churches lick their chops at the opportunity to excommunicate. A gospel-only community responds by saying, “We’re no better than he is so why does he have to lose his job? After all, don’t we believe in grace and forgiveness?” A one word community simply doesn’t possess the biblical wisdom or theological resources to know how to deal with sinners in an honest, loving, and appropriate way.

Explaining that we are a law-gospel community, I showed how pastorally this means we believe God uses his law to crush hard hearts and his gospel to cure broken hearts. The law is God’s first word; the gospel is God’s final word. And when we rush past God’s first word to get to God’s final word and the law has not yet had a chance to do its deep wrecking work, the gospel is not given a chance to do its deep restorative work. Sinners never experience the freedom that comes from crying “Abba” (gospel) until they first cry “Uncle” (law).

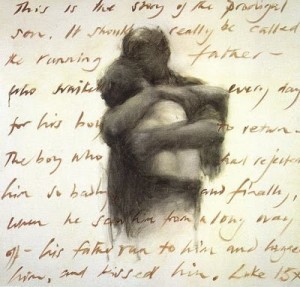

I illustrated this point by reminding our church that the Father of the prodigal son in Luke 15 did not fall to his knees and wrap his arms around his sons legs as the son was leaving, but as he was returning. He had been waiting, looking to the horizon in hope. When he saw his son coming home, crushed and humbled, he ran to him. But he didn’t stop him from leaving. He didn’t rescue his son from the pigsty. If we really love people and want to see them truly set free, we have to get out of God’s way and let the law do its crushing work so that the gospel can do its curing work. I’ve seen way too many lives ruined because parents, pastors, families, and friends have cushioned the fall of someone they love–robbing that person from ever experiencing true deliverance because they never experience true desperation. As John Zahl has said, “God’s office is at the end of our rope.” Grace always runs downhill–meeting us at the bottom, not the top.

I illustrated this point by reminding our church that the Father of the prodigal son in Luke 15 did not fall to his knees and wrap his arms around his sons legs as the son was leaving, but as he was returning. He had been waiting, looking to the horizon in hope. When he saw his son coming home, crushed and humbled, he ran to him. But he didn’t stop him from leaving. He didn’t rescue his son from the pigsty. If we really love people and want to see them truly set free, we have to get out of God’s way and let the law do its crushing work so that the gospel can do its curing work. I’ve seen way too many lives ruined because parents, pastors, families, and friends have cushioned the fall of someone they love–robbing that person from ever experiencing true deliverance because they never experience true desperation. As John Zahl has said, “God’s office is at the end of our rope.” Grace always runs downhill–meeting us at the bottom, not the top.

With tears in my eyes and deep longing in my heart, I ache for the day when I can look out on the horizon and see my crushed friend walking toward me. On that day I’ll know that God’s law has done it’s work. And when that happens, I will run to meet him, fall on my knees, wrap my arms around his legs, and throw a party. No questions asked. Just a party.

I’m waiting for you, my brother!

August 21, 2012

Three Things Suffering People Need

Here is Part 2 of my conversation with Dr. Paul Zahl a couple weeks ago. If you didn’t see Part 1, you can watch it here.

Who Will Deliver Us? The Present Power of the Death of Christ | Paul Zahl and Tullian Tchividjian from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

August 17, 2012

The Good News

I love the way Sean Norris of South Side Anglican Church in Pittsburgh describes what the gospel is on their church website.

The “good news” of Christianity begins by describing the way things are. There is much beauty and joy in our lives, but there is also pain, loss, dissatisfaction, and trauma. We wish we didn’t war with each other, but we do. No one wants to become an addict, but we do. No one wants their marriage to end in divorce, but it happens. We are not as free as we think. We are unable to fix ourselves, our family, or our world. Are we left alone?

“But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ— by grace you have been saved” (Ephesians 2:5).

The Gospel—literally the “good news”—is that God has descended into the depths of our failure, even into hell itself to rescue us. “But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ” (Ephesians 2:13). In Jesus, God himself took the consequences of our ignorance, our selfishness, our cowardice, and ultimately our rejection of him. Jesus alone reveals that God is not an angry judge but a loving father gathering his hurting children to himself to heal, to forgive, to redeem.

We are reconciled to God by faith through grace alone. As a result, we believe that the gospel is the same for all people, Christian and non alike. Only God’s grace unleashes freedom—the kind of freedom to accept, to forgive, to walk in love, to live boldly. “It is for freedom Christ has set us free” (Galatians 5:1). God’s forgiveness means that we are motivated by love instead of fear. The fruit of that freedom of the Gospel is a spontaneous, creative, and compassionate life.

We believe that the very thing that makes a Christian—namely, the Gospel—is the same thing that grows a Christian.

I’m grateful for Sean and his gospel witness. If you live anywhere near Pittsburgh, I recommend that you visit Sean’s young church plant.

August 13, 2012

A Theology Of Everyday Life

Two weeks ago, I sat down with Dr. Paul Zahl to talk about his book Grace in Practice: A Theology Of Everyday Life. Below is Part 1 of our conversation.

Grace in Practice: A Theology of Everyday Life | Paul Zahl and Tullian Tchividjian from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

August 9, 2012

Explanations Are A Substitute For Trust

Have you ever felt like you couldn’t share the details of a difficult situation without someone immediately offering a solution or a spiritual platitude? Have you ever responded that way yourself?

Have you ever felt like you couldn’t share the details of a difficult situation without someone immediately offering a solution or a spiritual platitude? Have you ever responded that way yourself?

The required cheerfulness that characterizes many of our churches produces a suffocating environment of pat, religious answers to the painful, complex questions that riddle the lives of hurting people. This culture of mandatory happiness actually promotes dishonesty and more suffering.

The Nobel Prize-winning social psychologist Daniel Kahneman has built a storied career proving the limits of self-knowledge when it comes to suffering. Even when we know where the hurt is coming from, we tend to respond in one of two ways: we moralize or we minimize.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, moralists interpret misfortune as the karmic result of misbehavior. This for that. “You failed to obey God, so He gave your child an illness.” Such rule-based economies of punishment and reward may be the default mode of the fallen human heart, but that doesn’t make them any less brutal. This does not mean that sin doesn’t have consequences. If you blow all of your money on booze, you will likely reap poverty, loneliness, and cirrhosis of the liver. Simple cause and effect. But to conclude that suffering people have somehow heaped up trouble for themselves on the Cosmic Registry and that God is doling out the misery in direct proportion would be more than mistaken; it would be cruel.

The second and equally counterproductive impulse when it comes to suffering is the one that minimizes.

Have you ever heard someone try to comfort a grieving friend, saying, “Death is a natural part of life”? The intention may be compassionate, but the recipient seldom experiences it that way. For them, you have just minimized their pain, implying that death and devastation are morally neutral, that our perceptions are what ultimately create the problem of pain—that if we were only able to detach from our emotions, we would experience peace in life, no matter the circumstances. And while there is a certain truth to that—Paul does ask, “Death, where is thy sting?” (1 Cor. 15:55 KJV)—in the moment, it can convey immense insensitivity.

Moreover, we minimize suffering when we instrumentalize it. That is, when we subordinate suffering to the result it might achieve, or when we reduce it to a glorified means of self-improvement, as certain daytime talk show hosts might be accused of doing. Christians, of course, use spiritual language to minimize suffering constantly, even their own. The need to exonerate God in the midst of tragedy— even to shove Bible verses in a person’s face (regardless of how profound or true they may be)—can be just as harmful as saying something actively discouraging, as if God were small enough to be invalidated by our individual suffering.

Both the moralizing and the minimizing approaches are attempts to keep suffering at bay, to play God. It is safe to say that when our faith (or lack thereof ) feels like a fight against the realities of suffering instead of a resource for accepting them, we are on the wrong track.

Writer and theologian Robert Farrar Capon has suggested that perhaps we need to “turn the question around—the message is for suffering and conflicted people. Christ on the cross meets us in our suffering and conflicts not in the promise to take them away here and now. He is simply with us in all our times.” Capon means that our hope is not “Jesus plus an explanation as to why suffering happens,” or “Jesus plus an explanation as to why you have this job, that spouse, or these circumstances or pain.” He is suggesting that God is especially present in suffering. Nothing proves this more than the Cross of Christ.

Writer and theologian Robert Farrar Capon has suggested that perhaps we need to “turn the question around—the message is for suffering and conflicted people. Christ on the cross meets us in our suffering and conflicts not in the promise to take them away here and now. He is simply with us in all our times.” Capon means that our hope is not “Jesus plus an explanation as to why suffering happens,” or “Jesus plus an explanation as to why you have this job, that spouse, or these circumstances or pain.” He is suggesting that God is especially present in suffering. Nothing proves this more than the Cross of Christ.

We may not ever fully understand why God allows the suffering that devastates our lives. We may not ever find the right answers to how we’ll dig ourselves out. There may not be any silver lining, especially not in the ways we would like. But we don’t need answers as much as we need God’s presence in and through the suffering itself. The truth is that when it comes to suffering, if we do not go to our graves in confusion we will not go to our graves trusting. Explanations are a substitute for trust.

For the life of the believer, one thing is beautifully and abundantly true: God’s chief concern in your suffering is to be with you and be Himself for you. And in the end, what we discover is that this really is enough.

(Excerpted from from my forthcoming book Glorious Ruin: How Suffering Sets You Free. You can pre-order it now and get it for under $10.)

August 6, 2012

God’s Two Words

The post below was taken from the introduction of the short devotional edited by Sean Norris entitled “Two Words: Teaser Edition” produced and published by my friends at Mockingbird Ministries.

The Bible addresses our everyday lives, full of problems and pressures. Contrary to popular belief, God does not approach us through His Word with a manual for living. He does not offer us a golden rule by which we can reach higher ground and begin to rid ourselves of our problem with sin. Instead, God comes to us through His Word in the midst of our problems, failure, and pain with an unexpected message that at first says, “The problem is much worse than you think.”

The Bible addresses our everyday lives, full of problems and pressures. Contrary to popular belief, God does not approach us through His Word with a manual for living. He does not offer us a golden rule by which we can reach higher ground and begin to rid ourselves of our problem with sin. Instead, God comes to us through His Word in the midst of our problems, failure, and pain with an unexpected message that at first says, “The problem is much worse than you think.”

We all want the doctor to walk in and say, “It’s not too bad. Don’t worry, you’ll be fine.” However, when we read the Bible, we discover that our problem is dire. God is the Doctor, and He enters our lives and delivers the most disturbing news: “You are dead.” Our initial response is one of disbelief and defiance. We think, You’re crazy! I am sitting right here talking to you. I know I don’t feel great, but I’m certainly not dead. We do not agree with the diagnosis God delivers through His Word.

Through the Law—the standards and demands presented in the Bible—we see that we are not, in fact, neutral beings who go astray here and there and just need to be brought around again with a little compassion and grace. Rather, we read that we are the stubborn and obstinate people that consistently rebel against God and His Law. We read that we are the dry bones in the valley of death. We are lost in the wilderness with no hope to find our way home. We are the sick that Jesus speaks of. We are born into death.

The Law is the “first Word” we hear from God when reading the Bible, and often it seems all too familiar. It seems to affirm the small, condemning voice in the back of our heads that tells us that we do not cut it. It is consistent with our knee-jerk judgments of other people. It is consistent with our everyday disappointments and pain. It is our death sentence, and it is devastating. It must be so, however, in order for us to hear God’s “second” and final Word.

Only when we die to our illusions of control, success, power, victory, and self-reliance can we be born again into new life. After the Doctor’s disturbing diagnosis, which makes us want to storm out and get another opinion, we finally are ready to hear the cure. Ironically, the cure is found in the same place as the diagnosis: at the cross. There, we see that we are indeed beyond self-repair and need nothing short of salvation. There, we find our cure in the sacrifice of the innocent man, God’s only Son, Jesus.

[Law and Gospel] are the “two Words” spoken by God. Through the Law, God wakes us up to our true condition of being “dead in our trespasses.” We find ourselves standing at the cross guilty, deserving to be justly nailed to it and hung for all to see. But then comes the more powerful and final Word, the Gospel. In our stead comes a broken, beaten, innocent Jesus to be nailed on the cross for us, to hang for us, to be ridiculed for us, to die for us. In His actions, we discover the true definition of love. Love that transcends death. Love that breathes new life into these dry bones. Love that breaks the chains of sin and death and sets us free. Love that gives hope. Love that is unconditional and self-sacrificing.

[Law and Gospel] are the “two Words” spoken by God. Through the Law, God wakes us up to our true condition of being “dead in our trespasses.” We find ourselves standing at the cross guilty, deserving to be justly nailed to it and hung for all to see. But then comes the more powerful and final Word, the Gospel. In our stead comes a broken, beaten, innocent Jesus to be nailed on the cross for us, to hang for us, to be ridiculed for us, to die for us. In His actions, we discover the true definition of love. Love that transcends death. Love that breathes new life into these dry bones. Love that breaks the chains of sin and death and sets us free. Love that gives hope. Love that is unconditional and self-sacrificing.

At the cross, God speaks His two Words simultaneously. The whole of the Bible points to this one moment. The Bible and all of life function according to these two Words. In every situation, you can see the Law at work for the purpose of driving people to know their need and find the answer to it in the Gospel.

This is Christianity.

August 1, 2012

How Are You Hiding From God?

There are two ways we can miss the mark of righteousness before God, two ways the relationship can be destroyed.

There are two ways we can miss the mark of righteousness before God, two ways the relationship can be destroyed.

One is more or less obvious: outright sinfulness, unrighteousness, lawlessness, self-indulgence, what the Bible would call “worldliness”,,. In other words, we can just say to God, “No thanks, I don’t want it, I’ll take my own chances.”

The other is much less obvious and more subtle, one that morally earnest people have much more trouble with: turning our back on the free gift and saying in effect, “I do agree with what you demand, but I don’t want charity. That’s too demeaning. So I prefer to do it myself. What you are offering is too cheap. I prefer the law to grace, thank-you very much. That seems safer to me.”

What this means, of course, is that secretly we find doing it ourselves more flattering to our self-esteem–the current circumlocution for pride. The law, that is, even the law of God–”the most salutary doctrine of life”– is used as a defense against the gift. Thus, the more we “succeed”, the worse off we actually are. The relationship to the giver of the free gift is broken…the Almighty God desires simply to be known as the giver of the gift of absolute grace. To this we say “no”. Then the relationship is destroyed just as surely as it was by our immorality. To borrow the language of addiction, it is the addiction that destroys the relationship…One can be addicted either to what is base or to what is high, either to lawlessness or lawfulness. Theologically there is not any difference since both break the relationship to God, the giver.

The law is not a remedy for sin. It does not cure sin. St. Paul says it was given to make sin apparent, indeed to increase it. It doesn’t do that necessarily by increasing immorality, although that can happen when rebellion or the power of suggestion leads us to do just what the law is against. But what the theologian of the cross sees clearly from the start is that, even more perversely, the law multiplies sin precisely through our morality, our misuse of the law and our “success” at it. It becomes a defense against the gift. That is the very essence of sin: refusing the gift and thereby setting what we do in the place of what God has done.

There is something in us that is always suspicious of or rebels against the gift. The defense that it is too cheap, easy, or morally dangerous is already the protest of the Old Adam and Eve who fear–rightly!–that their house is under radical attack. Since they are entrenched behind the very law of God as their last and most pious defense, the attack must indeed be radical. It is a battle to the death.

Gerhard Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, pg. 26-28

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers