Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 26

May 3, 2012

Stop It!

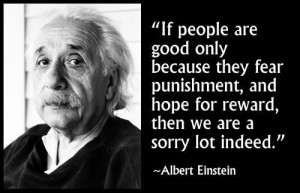

Take note preachers and parents: Believing that simply telling sinners to “stop it” (i.e., law without gospel) carries the power to exact lasting change is as silly and unrealistic as this:

April 29, 2012

Two-Hundred Proof Grace

John Dink has assembled some excellent quotes on his blog. This one from Robert Capon is one of my all-time favorites.

The Reformation was a time when men went blind, staggering drunk because they had discovered, in the dusty basement of late medievalism, a whole cellar full of fifteen-hundred-year-old, two-hundred proof Grace–bottle after bottle of pure distilate of Scripture, one sip of which would convince anyone that God saves us single-handedly. The word of the Gospel–after all those centuries of trying to lift yourself into heaven by worrying about the perfection of your bootstraps–suddenly turned out to be a flat announcement that the saved were home before they started…Grace has to be drunk straight: no water, no ice, and certainly no ginger ale; neither goodness, nor badness, not the flowers that bloom in the spring of super spirituality could be allowed to enter into the case. (Robert Farrar Capon, Between Noon and Three, pg. 114-115)

Reflecting on this quote, John writes, “Sola Gratia, Grace Alone, was not merely a leaning of the Reformation… it was a pillar. The reformers trumpeted God’s grace as the only Christian method, with no compromise. The Gospel was being unleashed again, not reinvented, but rediscovered… the unending love of God, freely given to the undeserving. The truth–so scandalous, so surprising, our hearts have to be sitting down to hear it… God saves sinners single-handedly, He will not be needing our help. In fact, diluting the Gospel with our own help is precisely why grace ceases to amaze us. So busy trying to help Jesus help us, we hardly ever taste His gift and we remain unchanged and unmoved by it. Over time, our blended, balanced, watered-down cup of grace leaves us cynical and sober. We want so desperately to mix in some of our rule-keeping or our performance… we’d give anything to add something of our own label! But it never turns out as we had hoped. We start to feel like we can’t keep up our end of the bargain – we feel as though we’ve failed. But… what if we don’t need our own label? What if Jesus kept up our end of the bargain for us? Those who are broken and bold enough to ask the questions, find themselves seated at a table with smiling sinners – too drunk on grace to remember the rules, and yet, they all seem to know them by heart. We’re served glass upon glass and something happens… the Gospel becomes the power of God and the wisdom of God. The power of God, because we taste something strong enough to save us. The wisdom of God, because we taste something good enough to change us. The bar is always open and the drinks are all paid for–just thank the Bar Tender, raise your glass and drink it straight. It’s all Grace.”

Reflecting on this quote, John writes, “Sola Gratia, Grace Alone, was not merely a leaning of the Reformation… it was a pillar. The reformers trumpeted God’s grace as the only Christian method, with no compromise. The Gospel was being unleashed again, not reinvented, but rediscovered… the unending love of God, freely given to the undeserving. The truth–so scandalous, so surprising, our hearts have to be sitting down to hear it… God saves sinners single-handedly, He will not be needing our help. In fact, diluting the Gospel with our own help is precisely why grace ceases to amaze us. So busy trying to help Jesus help us, we hardly ever taste His gift and we remain unchanged and unmoved by it. Over time, our blended, balanced, watered-down cup of grace leaves us cynical and sober. We want so desperately to mix in some of our rule-keeping or our performance… we’d give anything to add something of our own label! But it never turns out as we had hoped. We start to feel like we can’t keep up our end of the bargain – we feel as though we’ve failed. But… what if we don’t need our own label? What if Jesus kept up our end of the bargain for us? Those who are broken and bold enough to ask the questions, find themselves seated at a table with smiling sinners – too drunk on grace to remember the rules, and yet, they all seem to know them by heart. We’re served glass upon glass and something happens… the Gospel becomes the power of God and the wisdom of God. The power of God, because we taste something strong enough to save us. The wisdom of God, because we taste something good enough to change us. The bar is always open and the drinks are all paid for–just thank the Bar Tender, raise your glass and drink it straight. It’s all Grace.”

Are you busy mixing or do you drink grace straight? Are you always in a spiritual hurry or is your soul free to rest and raise a glass? Is it possible that free grace in Christ causes people to love like Christ?

John 1:16-17, Luke 10:38-42, Ezk 36:26-27

April 24, 2012

Three Ways We Say “No” To Law

I was in New York City this past weekend with some friends at The Mockingbird Conference. Best time in NYC I’ve ever had. The work and ministry of my friend David Zahl and his crew is simply the best in the biz. And I’m a hard guy to please. If you’re unfamiliar with Mockingbird, you HAVE to familiarize yourself with them. What they’re doing is unlike anything else.

I was in New York City this past weekend with some friends at The Mockingbird Conference. Best time in NYC I’ve ever had. The work and ministry of my friend David Zahl and his crew is simply the best in the biz. And I’m a hard guy to please. If you’re unfamiliar with Mockingbird, you HAVE to familiarize yourself with them. What they’re doing is unlike anything else.

Their mission is to connect the Christian faith with the everyday realities of life–”demonstrating and cataloging the myriad ways in which the Christian understanding of reality (what people are like, what God is like and how the two intersect) is born out all around us. We want to do so in a way that is both comforting and inspiring, taking care along the way to look for new words for the old story.” It’s gripping and provocative stuff.

They just published a new book entitled This American Gospel: Public Radio Parables and the Grace of God. I read the intro and first chapter last night. I laughed and cried. I felt my desperation and God’s deliverance profoundly. I connected deeply with this…I hope you do to.

The Law is shorthand for an accusing standard of performance. Whenever the Law is coming, accusation comes close behind. Whenever an expectation stands before us, we are either condemned by our failure before it, or we become condemners in our fulfillment of it. The Law is unfeeling–it tolerates no excuses, it accepts no shortcuts. The Law is good, in that it proffers a good standard (“You shouldn’t smoke”, “Love one another”, “Spend on the money you have”, etc.), but it is received as condemnation when one finds oneself incapable of fulfilling it. It is for this reason–our eventual and consistent failures–that the Law is condemnation’s prerequisite.

Failure before the Law always creates a reaction. When criticized, we defend. As Paul Zahl says, it is not so much the Law’s demand, but, “its second characteristic, it’s inability to produce the obedience it requires…we instinctively fight the law. We use a thousand arguments to criticize it and flour it. Obeying speed limits do not come naturally…”

You are brought to a moment of internal crisis, where something you are is in conflict with something you ought to be.

In the face of judgment, one response is flight. You run from what someone thinks you ought to be. You stop going to the gym, you leave home and experience the world through travel, you don’t answer their phone calls anymore, you close your eyes and cover your ears. The idea is: I know the judge isn’t leaving anytime soon, so I will. Sayonara!

Or perhaps you attempt to assassinate the judge; it’s not flight, it’s fight. You know the judge isn’t leaving anytime soon, but you’re not either, so it’s time to put up your dukes. You bicker with your boss about his unrealistic expectations, condescend about the vanity of going to the gym, blame your parents for what they’ve done to you, or wear leather and turn the speakers up.

Or maybe you appease. The judge isn’t satisfied, so you show him how hard you are trying, you’re sorry, and it’s going to get better. You decide to wear what they wear, apologize needlessly for fear they are mad at you, go to the gym from time to time and justify why you don’t go more often, or sit still and mind your manners so you don’t get barked at. Appeasement is cowering before the judge, hoping at some point the judge might understand and sympathize with your situation.

When the voice of accusation comes, how do you respond? Run? Fight? Appease? All three?

The deepest fear we have, “the fear beneath all fears”, is the fear of not measuring up, the fear of judgment. It’s this fear that creates the stress and depression of everyday life. And it comes from the fact that down deep we all know we don’t measure up and are therefore deserving of judgment. We’re aware that we fail, that what we are is not what we’re supposed to be, that “we’ve been weighed in the balances and been found wanting.” One young mother recently put it as honestly as anyone can:

Deep down, I know I should be perfect and I’m not. I feel it when someone comes into my house unannounced and there’s a mess in every corner. I know it when my children misbehave in public and I just want to hide. I can tell it when that empty feeling rises after I’ve spoken in haste, said too much, or raised my voice. There’s the feeling in my stomach that I just can’t shake when I know I’ve missed the mark of perfection.

When we feel this weight of judgment against us, we all tend to slip into the slavery of self-salvation: trying to appease the judge (friends, parents, spouse, ourselves) with hard work, good behavior, getting better, achievement, losing weight, and so on. We conclude, “If I can just stay out of trouble and get good grades, maybe my mom and dad will finally approve of me; If I can overcome this addiction, then I’ll be able to accept myself; If I can get thin, maybe my husband will finally think I’m beautiful and pay attention to me; If I can help out more with the kids, maybe my wife won’t criticize me as much; If I can make a name for myself and be successful, maybe I’ll get the respect I long for.” But, as is always the case, self-salvation projects experientially eclipse the only salvation project that can set us free from this oppression. “If we were confident of ultimate acquittal”, says Paul Zahl, “judgment from others would not possess the sting it does.”

This is what makes the Gospel such good news. It announces that Jesus came to acquit the guilty. He came to judge and be judged in our place. Christ came to satisfy the deep judgment against us once and for all so that we could be free from the judgment of God, others, and ourselves. He came to give rest to our efforts at trying to deal with stinging accusation on our own. Colossians 2:13-14 announces, “And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross.”

This is what makes the Gospel such good news. It announces that Jesus came to acquit the guilty. He came to judge and be judged in our place. Christ came to satisfy the deep judgment against us once and for all so that we could be free from the judgment of God, others, and ourselves. He came to give rest to our efforts at trying to deal with stinging accusation on our own. Colossians 2:13-14 announces, “And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross.”

The Gospel declares that our guilt has been atoned for, the law has been fulfilled. So we don’t need to live under the burden of trying to figure out whether we need to run, fight, or appease. In Christ the ultimate demand has been met, the deepest judgment has been satisfied. The atonement of Christ frees us from the fear of judgment.

April 20, 2012

Hiding From God Behind His Law

There are two ways we can miss the mark of righteousness before God, two ways the relationship can be destroyed.

There are two ways we can miss the mark of righteousness before God, two ways the relationship can be destroyed.

One is more or less obvious: outright sinfulness, unrighteousness, lawlessness, self-indulgence, what the Bible would call “worldliness” or, perhaps in more modern dress, carelessness or heedlessness. In other words, we can just say to God, “No thanks, I don’t want it, I’ll take my own chances.”

The other is much less obvious and more subtle, one that morally earnest people have much more trouble with: turning our back on the free gift and saying in effect, “I do agree with what you demand, but I don’t want charity. That’s too demeaning. So I prefer to do it myself. What you are offering is too cheap. I prefer the law to grace, thank-you very much. That seems safer to me.”

What this means, of course, is that secretly we find doing it ourselves more flattering to our self-esteem–the current circumlocution for pride. The law, that is, even the law of God–”the most salutary doctrine of life”– is used as a defense against the gift. Thus, the more we “succeed”, the worse off we actually are. The relationship to the giver of the free gift is broken…the Almighty God desires simply to be known as the giver of the gift of absolute grace. To this we say “no”. Then the relationship is destroyed just as surely as it was by our immorality. To borrow the language of addiction, it is the addiction that destroys the relationship…One can be addicted either to what is base or to what is high, either to lawlessness or lawfulness. Theologically there is not any difference since both break the relationship to God, the giver.

The law is not a remedy for sin. It does not cure sin. St. Paul says it was given to make sin apparent, indeed to increase it. It doesn’t do that necessarily by increasing immorality, although that can happen when rebellion or the power of suggestion leads us to do just what the law is against. But what the theologian of the cross sees clearly from the start is that, even more perversely, the law multiplies sin precisely through our morality, our misuse of the law and our “success” at it. It becomes a defense against the gift. That is the very essence of sin: refusing the gift and thereby setting what we do in the place of what God has done.

There is something in us that is always suspicious of or rebels against the gift. The defense that it is too cheap, easy, or morally dangerous is already the protest of the Old Adam and Eve who fear–rightly!–that their house is under radical attack. Since they are entrenched behind the very law of God as their last and most pious defense, the attack must indeed be radical. It is a battle to the death.

Gerhard Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, pg. 26-28

April 16, 2012

“Ifs” Kill!

One of the problems in the current conversation regarding the relationship between law and gospel is that the term “law” is not always used to mean the same thing. This is understandable since in the Bible “law” does not always mean the same thing.

One of the problems in the current conversation regarding the relationship between law and gospel is that the term “law” is not always used to mean the same thing. This is understandable since in the Bible “law” does not always mean the same thing.

For example, in Psalm 40:8 we read: “I delight to do your will, O my God; your law is within my heart.” Here the law is synonymous with God’s revealed will. A Christian seeking to express their love for God and neighbor delights in those passages that declare what God’s will is. When, however, Paul tells Christians that they are no longer under the law (Rom. 6:14) he obviously means more by law than the revealed will of God. He’s talking there about Christians being free from the curse of the law–not needing to depend on adherence to the law to establish our relationship to God: “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Rom. 10:4).

So, it’s not as simple as you might think. For short hand, I think it’s helpful to say that law is anything in the Bible that says “do”, while gospel is anything in the Bible that says “done”; law equals imperative and gospel equals indicative. However, when you begin to parse things out more precisely, you discover some important nuances that should significantly help the conversation forward so that people who are basically saying the same thing aren’t speaking different languages and talking right past one another.

Discussion of the law and it’s three uses (1) usus theologicus (drives us to Christ), (2) usus politicus (the civil use), and (3) usus practicus (revealing of God’s will for living) are helpful. But I’ve discovered that this outline all by itself raises just as many questions to those I talk to as it does provide answers. So, I’d like to offer some brief thoughts that you might find helpful (big shout-out to my friend Jono Linebaugh who has helped me tremendously in thinking these things through).

When, for instance, the Apostle Paul speaks about the law he routinely speaks of it as a command attached to a condition. In other words, law is a demand within a conditional framework. This is why he selects Leviticus 18:5b (both in Gal. 3 and Rom. 10) as a summary of the salvation-structure of the law: “if you keep the commandments, then you will live.” Here, there is a promise of life linked to the condition of doing the commandments and a corresponding threat for not doing them: “cursed is everyone who does not abide in all the things written in the Book of the Law, to do them” (Gal 3.10 citing Deut 27.26). When this conditional word encounters the sinful human, the outcome is inevitable: “the whole world is guilty before God” (Rom 3.19). It is the condition that does the work of condemnation. “Ifs” kill!

When, for instance, the Apostle Paul speaks about the law he routinely speaks of it as a command attached to a condition. In other words, law is a demand within a conditional framework. This is why he selects Leviticus 18:5b (both in Gal. 3 and Rom. 10) as a summary of the salvation-structure of the law: “if you keep the commandments, then you will live.” Here, there is a promise of life linked to the condition of doing the commandments and a corresponding threat for not doing them: “cursed is everyone who does not abide in all the things written in the Book of the Law, to do them” (Gal 3.10 citing Deut 27.26). When this conditional word encounters the sinful human, the outcome is inevitable: “the whole world is guilty before God” (Rom 3.19). It is the condition that does the work of condemnation. “Ifs” kill!

Compare this to a couple examples of New Testament imperatives. First, consider Galatians 5.1. After four chapters of passionate insistence that justification is by faith apart from works of the law, Paul issues a couple of strong imperatives: “It was for freedom that Christ set us free; therefore stand firm (imperative) and do not be subject (imperative) again to the yoke of slavery.” Are these commandments with conditions? No! Are these imperatives equal to Paul’s description of the law? No! The command here is precisely to not return to the law; it is an imperative to stand firm in freedom from the law.

Let’s say you’re a pastor and a college student comes to you for advice. He’s worn out because of the amount of things he’s involved in. He’s in a fraternity, playing basketball, running track, waiting tables, and taking 16 hours of credit. The pressure he feels from his family to “do it all” and “make something of himself” is making him crazy and wearing him down. After explaining his situation to you, you look at him and explain the gospel–that because Jesus paid it all we are free from the need to do it all. Our identity, worth, and value is not anchored in what we can accomplish but in what Jesus accomplished for us. Then you issue an imperative: “Now, quit track and drop one class.” Does he hear this as bad news or good news? Good news, of course. The very idea of knowing he can let something go brings him much needed relief–he can smell freedom. Like Galatians 5:1, the directive you issue to the student is a directive to not submit to the slavery of a command with a condition (law): “if you do more and try harder, you will make something of yourself and therefore find life.” It’s not an imperative of conditional command; it is an invitation to freedom and fullness. This is good news!

Or take another example, John 8.11. Once the accusers of the adulterous women left, Jesus said to her, “Neither do I condemn you. Depart. From now on, sin no more.” Does this final imperative disqualify the words of mercy? Is this a commandment with a condition? No! Otherwise Jesus would have instead said, “If you go and sin no more, then neither will I condemn you.” But Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you. Go and sin no more.” The command is not a condition. “Neither do I condemn you” is categorical and unconditional, it comes with no strings attached. “Neither do I condemn you” creates an unconditional context within which “go and sin no more” is not an “if.” The only “if” the gospel knows is this: “if anyone sins, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the Righteous” (1 John 2.1).

The reason Paul says that Christ is the end of this law is that in the gospel God unconditionally gives the righteousness that the law demands conditionally. So Christ kicks the law out of the conscience by overcoming the voice of condemnation produced by the condition of the law. As I said in my previous post, the conditional voice that says “Do this and live” gets out-volumed by the unconditional voice that says “It is finished.”

When this happens, we are freed from the condemnation of the law’s conditionality (the “law” loses its teeth) and therefore free to hear the law’s content as a description of what a free life looks like. In other words, the gospel ends the law’s role as the regulator of the divine-human relationship and limits the law to being a blueprint for the free life. So, the law serves Christians by showing us what freedom on the ground looks like. But everyday in various ways we disobey and stubbornly ignore the call to be free, “submitting ourselves once again to a yoke of slavery.” And when we do, it is the gospel which brings comfort by reminding us that God’s love for us doesn’t depend on what we do (or fail to do) but on what Christ has done for us. Jesus fulfilled all of God’s holy conditions so that our relationship to God could be wholly unconditional. “There is therefore now no condemnation for those that are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1). The gospel, therefore, always has the last word over a believer. Always!

When this happens, we are freed from the condemnation of the law’s conditionality (the “law” loses its teeth) and therefore free to hear the law’s content as a description of what a free life looks like. In other words, the gospel ends the law’s role as the regulator of the divine-human relationship and limits the law to being a blueprint for the free life. So, the law serves Christians by showing us what freedom on the ground looks like. But everyday in various ways we disobey and stubbornly ignore the call to be free, “submitting ourselves once again to a yoke of slavery.” And when we do, it is the gospel which brings comfort by reminding us that God’s love for us doesn’t depend on what we do (or fail to do) but on what Christ has done for us. Jesus fulfilled all of God’s holy conditions so that our relationship to God could be wholly unconditional. “There is therefore now no condemnation for those that are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1). The gospel, therefore, always has the last word over a believer. Always!

For Martin Luther, it is within this unconditional context created by the gospel–the reality he called “living by faith”–that the law understood as God’s good commands can be returned to its proper place. Wilfried Joest sums this up beautifully:

The end of the law for faith does not mean the denial of a Christian ethic…. Luther knows a commandment that gives concrete instruction and an obedience of faith that is consistent with the freedom of faith…. This commandment, however, is no longer the lex implenda [the law that must be fulfilled], but rather comes to us as the lex impleta [the law that is already fulfilled]. It does not speak to salvation-less people saying: ‘You must, in order that…’ It speaks to those who have been given the salvation-gift and say, “You may, because…”

Freed from the burden and bondage of attempting to use the law to establish our righteousness before God, Christians are free to look to “imperatives”, not as conditions, but as descriptions and directions as they seek to serve their neighbor. The law, in other words, norms neighbor love–it shows us what to do and how to do it. Once a person is liberated from the commonsense delusion that keeping the rules makes us right with God, and in faith believes the counter-intuitive reality that being made righteous by God’s forgiving and resurrecting word precedes and produces loving action (defined as serving our neighbor), then the justified person is unlocked to love–which is the fulfillment of the law.

April 11, 2012

Grace Prevails

When talking about "the law", we need to make an important distinction. We can call it big "L" Law and little "l" law. Big "L" law comes from God and is outlined in the Ten Commandments, reiterated in the Sermon on the Mount, and summarized by Jesus as the command to "Love the Lord with all of our heart, mind, soul, and strength…and love our neighbor" (of course, one could say more but that's the gist of it). But there's another law (little "l") that plays out in all kinds of ways in daily life. Paul Zahl puts it this way:

When talking about "the law", we need to make an important distinction. We can call it big "L" Law and little "l" law. Big "L" law comes from God and is outlined in the Ten Commandments, reiterated in the Sermon on the Mount, and summarized by Jesus as the command to "Love the Lord with all of our heart, mind, soul, and strength…and love our neighbor" (of course, one could say more but that's the gist of it). But there's another law (little "l") that plays out in all kinds of ways in daily life. Paul Zahl puts it this way:

Law with a small "l" refers to an interior principle of demand or ought that seems universal in human nature. In this sense, law is any voice that makes us feel we must do something or be something to merit the approval of another. For example, what we shall call "the law of capability" is the demand a person may feel that he/she be 100% capable in everything he/she does–or else! In the Bible, the Law comes from God. In daily living, law is an internalized principle of self-accusation. We might say that the innumerable laws we carry inside us are bastard children of the Law.

No one understood the dynamic of how the accusation of the law functions in the human psyche better than Martin Luther. He characterized the Law as, "a voice that man can never stop in this life," one that can be heard anywhere and everywhere, not just on Sunday morning. It takes any number of forms, but its function remains the same: it accuses. Indeed, the "oughts" of life are as numerous as they are oppressive: infomercials promising a better life if you work at getting a better body, a neighbor's new car, a beautiful person, the success of your co-worker- all these things have the potential to communicate "you're not enough."

The other day I was driving down the road near my house and I passed a sign in front of a store that read, "Life is the art of drawing without an eraser." Meant to inspire drivers-by to work hard, live well, and avoid mistakes, it served as a booming voice of law to everyone that read it: "Don't mess up. There are no second chances. You better get it right the first time." Again, Paul Zahl chimes in insightfully:

In practice, the requirement of perfect submission to the commandments of God is exactly the same as the requirement of perfect submission to the innumerable drives for perfection that drive everyday people's crippled and crippling lives. The commandment of God that we honor our father and mother is no different in impact, for example, than the commandment of fashion that a woman be beautiful or the commandment of culture that a man be boldly decisive and at the same time utterly tender.

The world is full to the brim with law. Not just laws of Scripture, laws of science, and tax codes, but lesser, subjective laws. And they cause us enormous grief. Indeed, identity is an area of life frequently mired in legalities: "I must be __________ kind of person, and not ___________ kind of person if I'm ever going to be somebody."

An environment of law, as we all know, is an environment of fear. We are afraid of the judgment that the law wields. Or as the poet Czeslaw Milosz describes in his poem "A Many-Tiered Man": "[Man] frightened of a verdict, now, for instance, or after his death." We instinctually know that if we don't measure up, the judge will punish us. When we feel this weight of judgment against us, we all tend to slip into the slavery of self-salvation: trying to appease the judge (friends, parents, spouse, ourselves) with hard work, good behavior, getting better, achievement, losing weight, and so on. We conclude, "If I can just stay out of trouble and get good grades, maybe my mom and dad will finally approve of me; If I can overcome this addiction, then I'll be able to accept myself; If I can get thin, maybe my husband will finally think I'm beautiful; if I can make a name for myself and be successful, maybe I'll get the respect I long for."

The law stifles and causes us to second-guess ourselves. Have you ever found yourself writing and rewriting the same email over and over again? Or procrastinating on making a phone call? The recipient almost inevitably has become a stand-in for the law. We put people in this role with alarming facility.

The idea of "law" simply makes sense, and universally so. The Apostle Paul even claims that it is written on the heart (Romans 2:15). In fact, those that don't believe in God tend to struggle with self-recrimination and self-hatred just as much as those that do; no one is free of guilt—the law is not subject to our belief in it. Some of us even compound our failures and suffering by heaping judgment upon judgment, intoxicated by the voice of "not-enoughness", not content until we have usurped the role of the only One who is actually qualified to pass a sentence. In a 2005 interview with journalist Michka Assayas, U2 frontman Bono spoke eloquently about Law and Grace in terms of Karma:

At the center of all religions is the idea of Karma. What you put out comes back to you: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, or in physics, every action is met by an equal and opposite one. It's clear to me that Karma is at the very heart of the Universe. I'm absolutely sure of it. And yet, along comes this idea called Grace to upend all that "as you reap, so will you sow" stuff. Grace defies reason and logic. Love interrupts the consequences of your actions, which in my case is very good news indeed, because I've done a lot of stupid stuff… I'd be in big trouble if Karma was going to finally be my judge. It doesn't excuse my mistakes, but I'm holding out for Grace. I'm holding out that Jesus took my sins onto the Cross, because I know who I am, and I hope I don't have to depend on my own religiosity.

Against the tumult of conditionality–punishment and reward, score-keeping, Karma, you-get-what-you-deserve, big "L" Law, little "l" law, whatever name you choose—comes the second of God's two words, His Grace. Grace is the gift that has no strings attached. It is one-way love. It is what makes the Good News so good, the once for all proclamation the there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:1). It is the simple equation that Jesus plus Nothing equals Everything.

Against the tumult of conditionality–punishment and reward, score-keeping, Karma, you-get-what-you-deserve, big "L" Law, little "l" law, whatever name you choose—comes the second of God's two words, His Grace. Grace is the gift that has no strings attached. It is one-way love. It is what makes the Good News so good, the once for all proclamation the there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:1). It is the simple equation that Jesus plus Nothing equals Everything.

The Gospel of Grace announces that Jesus came to acquit the guilty–he came to judge and be judged in our place. Christ came to satisfy the deep judgment against us once and for all so that we could be free from the judgment of God, others, and ourselves. He came to give rest to our efforts at trying to deal with judgment on our own. The Gospel declares that our guilt has been atoned for, the law has been fulfilled. So we don't need to live under the burden of trying to appease the judgment we feel; in Christ the ultimate demand has been met, the deepest judgment has been satisfied. The internal voice that says "Do this and live" only get's outvolumed by the external voice that says "It is finished!"

Yet there is nothing that is harder for us to wrap our minds around than the unconditional, non-contingent grace of God. In fact, it "defies our reason and logic," upending our sense of fairness and offending our deepest intuitions, especially when it comes to those who have done us harm. Like Job's friends, we insist that reality operate according to the predictable economy of reward and punishment. Like the elder brother in the Parable of the Prodigal son, we have worked too hard to give up now. The storm may be raging all around us, our foundations may be shaking, but we would rather perish than give up our "rights."

Yet still the grace of God prevails! His gracious disposition toward us thankfully does not depend even on our ability to comprehend it. When we finally come to the end of ourselves, there it will be. There He will be. Just as He will be the next time we come to the end of ourselves, and the time after that, and the time after that.

April 6, 2012

Law And Gospel: Part 4

J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted that "A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace." The reason this seems so counter-intuitive is because most people think that those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God's law (hence, the regular charge of antinomianism). Others think that those with a high view of the law are the legalists. But Machen makes the very compelling point that it's a low view of the law that produces legalism because a low view of the law causes us to conclude that we can do it–the bar is low enough for us to jump over. A low view of the law makes us think that the standards are attainable, the goals are reachable, the demands are doable. It's this low view of the law that caused Immanuel Kant to conclude that "ought implies can." That is, to say that I ought to do something is to imply logically that I am able to do it.

J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted that "A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace." The reason this seems so counter-intuitive is because most people think that those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God's law (hence, the regular charge of antinomianism). Others think that those with a high view of the law are the legalists. But Machen makes the very compelling point that it's a low view of the law that produces legalism because a low view of the law causes us to conclude that we can do it–the bar is low enough for us to jump over. A low view of the law makes us think that the standards are attainable, the goals are reachable, the demands are doable. It's this low view of the law that caused Immanuel Kant to conclude that "ought implies can." That is, to say that I ought to do something is to imply logically that I am able to do it.

A high view of the law, however, demolishes all notions that we can do it–it exterminates all attempts at self-sufficient moral endeavor. We'll always maintain a posture of suspicion regarding the radicality of unconditional grace as long as we think we have the capacity to pull it off. Only an inflexible picture of what God demands is able to penetrate the depth of our need and convince us that we never outgrow our need for grace–that grace never gets overplayed. "Our helplessness before the totality of Divine expectation is what creates the space for God's amazing grace and the freedom it produces." The way of God's grace becomes absolutely indispensable because the way of God's law is absolutely inflexible.

So a high view of law equals a high view of grace. A low view of law equals a low view of grace.

Carefully showing the distinct roles of the law and the gospel, John Calvin wrote:

The Gospel is the message, the salvation-bringing proclamation, concerning Christ that he was sent by God the Father…to procure eternal life. The Law is contained in precepts, it threatens, it burdens, it promises no goodwill. The Gospel acts without threats, it does not drive one on by precepts, but rather teaches us about the supreme goodwill of God towards us.

As Christians, we still need to hear both the law and the gospel. We need to hear the law because we are all, even after we're saved, prone to wander in a "I can do it" direction. The law, said Luther, is a divinely sent Hercules to attack and kill the monster of self-righteousness-a monster that continues to harass the Redeemed. The law shows non-Christians and Christians the same thing: how we can't cut it on our own and how much we both need Jesus. Sinners need constant reminders that our best is never good enough and that "there is something to be pardoned even in our best works." We need the law to strip us of our fig leaves. We need the law to freshly reveal to us that we're a lot worse off than we think we are and that we never outgrow our need for the cleansing blood of Christ.

Regardless of how well I think I'm doing in the sanctification project or how much progress I think I've made since I first became a Christian, like Paul in Romans 7, when God's perfect law becomes the standard and not "how much I've improved over the years", I realize that I'm a lot worse than I fancy myself to be. Whatever I think my greatest vice is, God's law shows me that my situation is much graver: if I think it's anger, the law shows me that it's actually murder; if I think it's lust, the law shows me that it's actually adultery; if I think it's impatience, the law shows me that it's actually idolatry (read Matthew 5:17-48). No matter how decent I think I'm becoming, when I'm graciously confronted by God's law, I can't help but cry out, "Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death" (Romans 7:24). The law alone shows us how desperate we are for outside help. In other words, we need the law to remind us everyday just how much we need the gospel everyday.

And then once we are re-crushed by the law, we need to be reminded that "Jesus paid it all." Even in the life of the Christian, the law continues to drive us back to Christ-to that man's cross, to that man's blood, to that man's righteousness. The gospel announces to failing, forgetful people that Jesus came to do for sinners what sinners could never do for themselves. The law demands that we do it all; the gospel declares that Jesus paid it all–that God's grace is gratuitous, that his love is promiscuous, and that while our sin reaches far, his mercy reaches farther. The gospel declares that Jesus came, not to abolish the law, but to fulfill it–that Jesus met all of God's perfect conditions on our behalf so that our relationship with God could be unconditional.

And then once we are re-crushed by the law, we need to be reminded that "Jesus paid it all." Even in the life of the Christian, the law continues to drive us back to Christ-to that man's cross, to that man's blood, to that man's righteousness. The gospel announces to failing, forgetful people that Jesus came to do for sinners what sinners could never do for themselves. The law demands that we do it all; the gospel declares that Jesus paid it all–that God's grace is gratuitous, that his love is promiscuous, and that while our sin reaches far, his mercy reaches farther. The gospel declares that Jesus came, not to abolish the law, but to fulfill it–that Jesus met all of God's perfect conditions on our behalf so that our relationship with God could be unconditional.

God's good law reveals our desperation; God's good gospel reveals our deliverer. We are in constant need of both. But we need to carefully distinguish them, understand their unique job descriptions, and never depend on the one to do what only the other can.

The Law discovers guilt and sin, And shows how vile our hearts have been. The Gospel only can express, Forgiving love and cleansing grace. (Isaac Watts)

While there is so much more that can be said about the law and the gospel, I have to bring this short mini-series to a close. And to conclude, I thought it might be helpful to post the sermon below. Back in the fall, I preached from Romans 7 at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary on the importance of distinguishing between the law and the gospel.

April 3, 2012

Law And Gospel: Part 3

Believe it or not, the purity of the Gospel's proclamation depends on the distinction between Law and Gospel.

Believe it or not, the purity of the Gospel's proclamation depends on the distinction between Law and Gospel.

James Nestingen wrote:

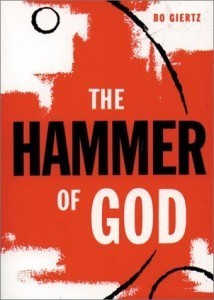

When the Law and Gospel are improperly distinguished, both are undermined. Separated from the Law, the Gospel gets absorbed into an ideology of tolerance in which leniency is equated with grace. Separated from the Gospel, the Law becomes an insatiable demand hammering away at the conscience until it destroys a person.

When the Law and Gospel are properly distinguished, however, both are established. The Law can be set forth in its full-scale demand, so that it lights the way to order and, through the work of the Spirit, drives us to Christ. The Gospel can be declared in all of its purity, so that forgiveness of sins and deliverance from the powers of death and the devil are bestowed in the presence of our crucified and risen Lord.

Or, to put it another way, "The failure to distinguish the law and the gospel always means the abandonment of the gospel" (Gerhard Ebeling). A confusion of law and gospel is the main contributor to moralism in the church simply because the law gets softened into "helpful tips for practical living", instead of God's unwavering demand for absolute perfection. While the gospel gets hardened into a set of moral and social demands that "we must live out", instead of God's unconditional declaration that "God justifies the ungodly." As my friend Jono Linebaugh says, "God doesn't serve mixed drinks. The divine cocktail is not law mixed with gospel. God serves two separate shots: law then gospel."

As I mentioned in my previous post, while there are a host of great resources available to help you better understand the important distinction between the law and the gospel, I found the most helpful resource to be John Pless' easy-to-read Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today. In the first chapter he summarizes C.F.W. Walther's six ways in which the law and the gospel are different. I've already highlighted the first three. Below are the second three. Recovering this distinction is THE answer to the church rediscovering the gospel in our day:

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Fourth, Law and Gospel are distinct when it comes to threats. Walther puts it simply: "The Gospel contains no threats at all, but only words of consolation. Wherever in Scripture you come across a threat, you may be assured that the passage belongs in the Law" (Walther, 11). The Law threatens sinners with punishment, pronouncing a curse on all who fail to live up to its requirements (Deuteronomy 27:26). The Gospel announces forgiveness for those crushed by the threat of the Law, for Christ Jesus came into the world to rescue the unrighteous (1 Timothy 1:15).

Fifth, the effects of Law and Gospel are different. Walther summarizes the threefold effect of the Law: (1) It demands but does not enable compliance. (2) It hurls people into despair, for it diagnoses the disease but provides no cure. (3) It produces contrition, that is, it terrifies the conscience but offers no comfort. Walther echoes the early Lutheran hymn writer Paul Speratus, who captured the biblical teaching of the Law's lethal effectiveness:

What God did in is Law demand

And none to him could render

Caused wrath and woe on ev'ry hand

For man, the vile offender.

Our flesh has not those pure desires

The spirit of the Law requires,

And lost is our condition.

It was a false, misleading dream

The God his Law had given

That sinners could themselves redeem

And by their works gain heaven.

The Law is but a mirror bright

To bring the inbred sin to light

That lurks within our nature.

Public debates have raged over whether or not the Ten Commandments should be displayed in courtrooms and classrooms. Sometimes well-meaning people have argued that placards containing the Ten Commandments would have a positive effect on public morality. Actually, Scriptures teach that the Law makes matters worse, not better. Knowledge of the Law does not entail the ability to keep it. The Law not only identifies the sin but also, like a swift kick to a sleeping dog that arouses the animal to bark and bite, the Law stirs up the power of sin (Romans 7:7-9). The Law brings death, not life, for it is a letter that kills (2 Corinthians 3:6). Without the Gospel, the Law can only be the cause for grief, as it was in the case of the rich young man who thought himself capable of keeping the Law (Matthew 19:22).

At each point, the Gospel is completely different from the Law. While it is only through faith that we receive the benefits of the Gospel, the Gospel itself creates faith (Romans 1:16; Ephesians 2:8-10). Rather than provoking terror of conscience, anguish of heart, and fear of condemnation like the Law, the Gospel stills every voice of accusation with the strong words of Christ's own peace and joy guaranteed by the blood of the cross. The Gospel does not set in place requirements of something that we must do or contribute. "[T]he Gospel does not require anything good that man must furnish: not a good heart, not a good disposition, no improvement of his condition, no godliness, no love of either God or men. It issues no orders, but changes man. It plants love into his heart and makes him capable of all good works. It demands nothing, but gives all. Should not this fact make us leap for joy?" (Walther, 16).

Sixth, Law and Gospel are to be distinguished in relation to the persons who are addressed, "The Law is to be preached to secure sinners and the Gospel to alarmed sinners" (Walther, 17). The secure sinner is the person who glories in his own self-righteous-ness. In the words of Lutheran theologian Gerhard Forde, the secure sinner is "addicted either to what is base or to what is high, either to lawlessness or to lawfulness. Theologically there is not any difference since both break the relationship to God, the giver." Addicted to that which is base, secure sinners will excuse or rationalize their sinful behavior. They will live, to use the words of the confessional prayer, "as if God did not matter and as if I mattered most." They will assert that their body and life and that of their neighbors are theirs to do with as they please. Or secure sinners might be addicted to that which is high. Like the Pharisee in Jesus' parable (Luke 18:9-14), secure sinners will trust in their own righteousness, their self-made spirituality., The sinners who are snug in their own righteousness rehearse the Ten Commandments and conclude that they, like the rich young man in the Gospel narrative, have kept all of these rules and are deserving of God's approval. To those ensnared in either of these securities, blind to God's demand for total righteousness, the Law is to be proclaimed full blast so all presumption might be destroyed.

Sixth, Law and Gospel are to be distinguished in relation to the persons who are addressed, "The Law is to be preached to secure sinners and the Gospel to alarmed sinners" (Walther, 17). The secure sinner is the person who glories in his own self-righteous-ness. In the words of Lutheran theologian Gerhard Forde, the secure sinner is "addicted either to what is base or to what is high, either to lawlessness or to lawfulness. Theologically there is not any difference since both break the relationship to God, the giver." Addicted to that which is base, secure sinners will excuse or rationalize their sinful behavior. They will live, to use the words of the confessional prayer, "as if God did not matter and as if I mattered most." They will assert that their body and life and that of their neighbors are theirs to do with as they please. Or secure sinners might be addicted to that which is high. Like the Pharisee in Jesus' parable (Luke 18:9-14), secure sinners will trust in their own righteousness, their self-made spirituality., The sinners who are snug in their own righteousness rehearse the Ten Commandments and conclude that they, like the rich young man in the Gospel narrative, have kept all of these rules and are deserving of God's approval. To those ensnared in either of these securities, blind to God's demand for total righteousness, the Law is to be proclaimed full blast so all presumption might be destroyed.

To those who have been crushed by the hammer blows of the Law, no longer secure in their lawlessness or self-righteousness, there is only one word that will do. That is the word of the Gospel. The Gospel is not a recipe for self-improvement. It is that word of God that declares sins to be forgiven for the sake of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ. It is all about Christ and what He has done for us. "Law is to be called, and to be, anything that refers to what we are to do. On the other hand, the Gospel, or the Creed, is any doctrine or word of God which does not require works from us and does not command us to do something, but bids us simply accept as a gift the gracious forgiveness of our sins and everlasting bliss offered us" (Walther, 19).

When Law and Gospel are muddled or mixed, the Holy Scriptures will be misread and misused. Without the right distinction of the Law from the Gospel, the Bible appears to be a book riddled with contradiction. At one place it condemns and at another it pardons. One text speaks of God's wrath visited upon sinners, while another declares His undying love for His enemies. Throughout both the Old and the New Testaments, the Scriptures reveal both God's wrath and His favor. The Scriptures show us a God who kills and who makes alive. This God does through two different words. With the word of His Law, sinners are put to death. It is only through the word of the Gospel that spiritual corpses are resurrected to live in Jesus Christ.

March 28, 2012

Law And Gospel: Part 2

If we are going to understand the Bible rightly, we have to be able to distinguish properly between God's two words: law and gospel. All of God's Word in the Bible comes to us in two forms of speech: God's word of demand (law) and God's word of deliverance (gospel). The law tells us what to do and the gospel tells us what God has done. As I mentioned in my previous post, both God's law and God's gospel are good and necessary, but both do very different things. Serious life confusion happens when we fail to understand their distinct "job descriptions." We'll wrongly depend on the law to do what only the gospel can do, and vice versa.

If we are going to understand the Bible rightly, we have to be able to distinguish properly between God's two words: law and gospel. All of God's Word in the Bible comes to us in two forms of speech: God's word of demand (law) and God's word of deliverance (gospel). The law tells us what to do and the gospel tells us what God has done. As I mentioned in my previous post, both God's law and God's gospel are good and necessary, but both do very different things. Serious life confusion happens when we fail to understand their distinct "job descriptions." We'll wrongly depend on the law to do what only the gospel can do, and vice versa.

For example, Kim and I have three children: Gabe (17), Nate (15), and Genna (10). In order to function as a community of five in our home, rules need to be established–laws need to be put in place. Our kids know that they can't steal from each other. They have to share the computer. Since harmonious relationships depend on trust, they can't lie. Because we have two cars and three drivers, Gabe can't simply announce that he's taking one of the cars. He has to ask ahead of time. And so on and so forth. Rules are necessary. But telling them what they can and cannot do over and over can't change their heart and make them want to comply.

When one of our kids (typically Genna) throws a temper tantrum, thereby breaking one of the rules, we can send her to her room and take away some of her privileges. And we do. But while this may rightly produce sorrow at the revelation of her sin, it does not have the power to remove her sin. In other words, the law can crush her but it cannot cure her–it can kill her but it cannot make her alive. If Kim and I don't follow-up the law with the gospel, Genna would be left without hope–defeated but not delivered. The law illuminates sin but is powerless to eliminate sin. That's not part of its job description. It points to righteousness but can't produce it. It shows us what godliness is, but it cannot make us godly. As Martin Luther said, "Sin is not canceled by lawful living, for no person is able to live up to the Law. Nothing can take away sin except the grace of God."

While there are a host of great resources available to help you better understand the important distinction between the law and the gospel, I found the most helpful resource to be John Pless' easy-to-read Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today. In the first chapter he summarizes C.F.W. Walther's six ways in which the law and the gospel are different. I will highlight the first three today and the second three later this week.

While there are a host of great resources available to help you better understand the important distinction between the law and the gospel, I found the most helpful resource to be John Pless' easy-to-read Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today. In the first chapter he summarizes C.F.W. Walther's six ways in which the law and the gospel are different. I will highlight the first three today and the second three later this week.

First, the Law differs from the Gospel by the manner in which it is revealed. The Law is inscribed in the human heart, and though it is dulled by sin, the conscience bears witness to its truth (Romans 2:14-15). "The Ten Commandments were published only for the purpose of bringing out in bold outline the dulled script of the original Law written in men's hearts" (Walther, 8). That is why the moral teachings of non-Christian religions are essentially the same as those found in the Bible. Yet it is different with the Gospel. The Gospel can never be known from the conscience. It is not a word from within the heart; it comes from outside. It comes from Christ alone. "All religions contain portions of the Law. Some of the heathen, by their knowledge of the Law, have advanced so far that they have even perceived the necessity of an inner cleansing of the soul, a purification of the thoughts and desires. But of the Gospel, not a particle is found anywhere except in the Christian religion" (Walther, 8). The fact that humanity is alienated from God, in need of cleansing and reconciliation, is a theme common to many belief systems. It is only Christianity that teaches that God himself justifies the ungodly.

Second, the Law is distinct from the Gospel in regard to content. The Law can only make demands. It tells us what we must do, but it is impotent to redeem us from its demands (Galatians 3:12-14). The Law speaks to our works, always showing that even the best of them are tainted with the fingerprints of our sin and insufficient for salvation. The Gospel contains no demand, only the gift of God's grace and truth in Christ. It has nothing to say about works of human achievement and everything to say about the mercy of God for sinners. "The Law tells us what we are to do. No such instruction is contained in the Gospel. On the contrary, the Gospel reveals to us only what God is doing. The Law is speaking concerning our works; the Gospel, concerning the great works of God" (Walther, 9).

Third, the Law and the Gospel differ in the promises that each make. The Law offers great good to those who keep its demands. Think what life would be like in a world where the Ten Commandments were perfectly kept. Imagine a universe where God was feared, loved, and trusted above all things and the neighbor was loved so selflessly that there would be no murder, adultery, theft, lying, or coveting. Indeed such a world would be paradise. This is what the Law promises. There is only one stipulation: that we obey its commands perfectly. "Do the Law and you will live", says Holy Scripture (Leviticus 18:5; Luke 10:25-28). The Gospel, by contrast, makes a promise without demand or condition. It is a word from God that does not cajole or manipulate, but simply gives and bestows what it says, namely, the forgiveness of sins. Luther defined the Gospel as "a preaching of the incarnate Son of God, given to us without any merit on our part for salvation and peace. It is a word of salvation, a word of grace, a word of comfort, a word of joy, a voice of the bridegroom and the bride, a good word, a word of peace." This is the word that the church is to proclaim throughout the world (Mark 16:15-16). It is the message that salvation is not achieved but received by grace through faith alone. (Ephesians 2:8-9). The Gospel is a word that promises blessing to those who are cursed, righteousness to the unrighteous, and life to the dead.

Law and Gospel: Part 2

If we are going to understand the Bible rightly, we have to be able to distinguish properly between God's two words: law and gospel. All of God's Word in the Bible comes to us in two forms of speech: God's word of demand (law) and God's word of deliverance (gospel). The law tells us what to do and the gospel tells us what God has done. As I mentioned in my previous post, both God's law and God's gospel are good and necessary, but both do very different things. Serious life confusion happens when we fail to understand their distinct "job descriptions." We'll wrongly depend on the law to do what only the gospel can do, and vice versa.

If we are going to understand the Bible rightly, we have to be able to distinguish properly between God's two words: law and gospel. All of God's Word in the Bible comes to us in two forms of speech: God's word of demand (law) and God's word of deliverance (gospel). The law tells us what to do and the gospel tells us what God has done. As I mentioned in my previous post, both God's law and God's gospel are good and necessary, but both do very different things. Serious life confusion happens when we fail to understand their distinct "job descriptions." We'll wrongly depend on the law to do what only the gospel can do, and vice versa.

For example, Kim and I have three children: Gabe (17), Nate (15), and Genna (10). In order to function as a community of five in our home, rules need to be established–laws need to be put in place. Our kids know that they can't steal from each other. They have to share the computer. Since harmonious relationships depend on trust, they can't lie. Because we have two cars and three drivers, Gabe can't simply announce that he's taking one of the cars. He has to ask ahead of time. And so on and so forth. Rules are necessary. But telling them what they can and cannot do over and over won't change their heart.

When one of our kids (typically Genna) throws a temper tantrum, thereby breaking one of the rules, we can send her to her room and take away some of her privileges. But neither the rule nor the enforcement of punishment has the power to make her sorry for what she's done. At best, it can only produce "legal repentance"–an external sorrow motivated by a self-preservational fear of getting punished again. For Kim and I to depend on the law to accomplish for Genna what only the gospel can accomplish, would be a huge mistake–as if imposing rules and enforcing consequences carries the power to effect heart change. The law reveals sin but is powerless to remove sin. That's not part of its job description. It points to righteousness but can't produce it. It shows us what godliness is, but it cannot make us godly. As Martin Luther said, "Sin is not canceled by lawful living, for no person is able to live up to the Law. Nothing can take away sin except the grace of God."

While there are a host of great resources available to help you better understand the important distinction between the law and the gospel, I found the most helpful resource to be John Pless' easy-to-read Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today. In the first chapter he summarizes C.F.W. Walther's six ways in which the law and the gospel are different. I will highlight the first three today and the second three later this week.

While there are a host of great resources available to help you better understand the important distinction between the law and the gospel, I found the most helpful resource to be John Pless' easy-to-read Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today. In the first chapter he summarizes C.F.W. Walther's six ways in which the law and the gospel are different. I will highlight the first three today and the second three later this week.

First, the Law differs from the Gospel by the manner in which it is revealed. The Law is inscribed in the human heart, and though it is dulled by sin, the conscience bears witness to its truth (Romans 2:14-15). "The Ten Commandments were published only for the purpose of bringing out in bold outline the dulled script of the original Law written in men's hearts" (Walther, 8). That is why the moral teachings of non-Christian religions are essentially the same as those found in the Bible. Yet it is different with the Gospel. The Gospel can never be known from the conscience. It is not a word from within the heart; it comes from outside. It comes from Christ alone. "All religions contain portions of the Law. Some of the heathen, by their knowledge of the Law, have advanced so far that they have even perceived the necessity of an inner cleansing of the soul, a purification of the thoughts and desires. But of the Gospel, not a particle is found anywhere except in the Christian religion" (Walther, 8). The fact that humanity is alienated from God, in need of cleansing and reconciliation, is a theme common to many belief systems. It is only Christianity that teaches that God himself justifies the ungodly.

Second, the Law is distinct from the Gospel in regard to content. The Law can only make demands. It tells us what we must do, but it is impotent to redeem us from its demands (Galatians 3:12-14). The Law speaks to our works, always showing that even the best of them are tainted with the fingerprints of our sin and insufficient for salvation. The Gospel contains no demand, only the gift of God's grace and truth in Christ. It has nothing to say about works of human achievement and everything to say about the mercy of God for sinners. "The Law tells us what we are to do. No such instruction is contained in the Gospel. On the contrary, the Gospel reveals to us only what God is doing. The Law is speaking concerning our works; the Gospel, concerning the great works of God" (Walther, 9).

Third, the Law and the Gospel differ in the promises that each make. The Law offers great good to those who keep its demands. Think what life would be like in a world where the Ten Commandments were perfectly kept. Imagine a universe where God was feared, loved, and trusted above all things and the neighbor was loved so selflessly that there would be no murder, adultery, theft, lying, or coveting. Indeed such a world would be paradise. This is what the Law promises. There is only one stipulation: that we obey its commands perfectly. "Do the Law and you will live", says Holy Scripture (Leviticus 18:5; Luke 10:25-28). The Gospel, by contrast, makes a promise without demand or condition. It is a word from God that does not cajole or manipulate, but simply gives and bestows what it says, namely, the forgiveness of sins. Luther defined the Gospel as "a preaching of the incarnate Son of God, given to us without any merit on our part for salvation and peace. It is a word of salvation, a word of grace, a word of comfort, a word of joy, a voice of the bridegroom and the bride, a good word, a word of peace." This is the word that the church is to proclaim throughout the world (Mark 16:15-16). It is the message that salvation is not achieved but received by grace through faith alone. (Ephesians 2:8-9). The Gospel is a word that promises blessing to those who are cursed, righteousness to the unrighteous, and life to the dead.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers