Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 28

February 10, 2012

I Can't Trust God To Be Unmerciful

Robert Frost, America's grand old man of poetry in the twentieth century, occasionally explored God and faith in his earlier poems. Then, entering his seventies after a decade of great personal loss—his wife's death, the death of one of his daughters shortly after childbirth, and the suicide of another—Frost wrote two poetic dramas filled with references to God. The first, A Masque of Reason, is based on Job's story of suffering and comes across as rather inconclusive. But the second, A Masque of Mercy, has Jonah as the main character and wraps up in a more aesthetically pleasing way. In creative uniqueness it tackles the conflict in Jonah's thinking, as it "explores the ancient riddle of how God can be just and also be merciful." It also pulls Jonah toward Christ and the cross.

Robert Frost, America's grand old man of poetry in the twentieth century, occasionally explored God and faith in his earlier poems. Then, entering his seventies after a decade of great personal loss—his wife's death, the death of one of his daughters shortly after childbirth, and the suicide of another—Frost wrote two poetic dramas filled with references to God. The first, A Masque of Reason, is based on Job's story of suffering and comes across as rather inconclusive. But the second, A Masque of Mercy, has Jonah as the main character and wraps up in a more aesthetically pleasing way. In creative uniqueness it tackles the conflict in Jonah's thinking, as it "explores the ancient riddle of how God can be just and also be merciful." It also pulls Jonah toward Christ and the cross.

The brief play is set late on a stormy night inside a modern bookstore run by someone named Keeper, a pagan skeptic who'll later say, "I'd rather be lost in the woods than found in church." His alcohol-loving wife, Jesse Bel, is more openly searching for faith and sees that longing in others around her as well: "The world seems crying out for a Messiah," she'll say.

The play begins with Keeper and Jesse Bel locking their shop's door for the evening, leaving inside a customer named Paul (as it turns out, it's the Paul—the apostle). But someone bangs at the locked door. As they reluctantly let him in, the harried stranger exclaims, "God's after me!"

"You mean the Devil is," Jesse Bel remarks.

"No, God."

"I never heard of such a thing," she protests.

The fugitive answers, "Haven't you heard of Thompson's 'Hound of Heaven'?"

Paul at once interjects by quoting the familiar opening lines: "I fled Him, down the nights and down the days; I fled Him, down the arches of the years."

But Keeper grumbles at the fugitive: "This is a bookstore—not a sanctuary."

From this strange and amusing start, the play proceeds to an extended conversation that keeps coming back to God.

"Why is God after you?" Keeper asks. "To save your soul?"

"No," the fugitive replies. He tells them he's a prophet, and his name is Jonah. He's been sent seven times "to prophesy against the city evil."

"What have you got against the city?" Keeper asks.

"He knows," Jonah answers. God knows.

Jonah identifies himself further (though Paul has already caught on): "I'm in the Bible, all done out in story." Then he complains, "I can't trust God to be unmerciful."

Paul responds, "There you have the beginning of all wisdom."

Jonah tells them about his earlier flight from God, and the storm, and the boat, and the crew—and the whale.

Jesse Bel sympathizes: "You poor, poor swallowable little man."

But Paul recognizes a man who needs rescue. He goes up to Jonah and crosses his forearms—to illustrate the cross.

"What good is that?" Jonah asks.

Jonah tells these three that he would like to announce an earthquake to destroy "the city evil," but he's sure God wouldn't send it. "Nothing would happen," he says—but suddenly a tremor sends books crashing from the store's shelves. Meanwhile, Jonah keeps hearing noises that he suspects are from God in pursuit of him.

Paul asks Jonah what he wants to see in God, if not mercy.

Justice is Jonah's answer; justice "before all else."

Throughout Frost's play, Jonah wrestles with how God doesn't seem to live up to justice. Jonah has been taught that people should be "strong, careful, thrifty, diligent," and he's upset by God's "modern tendency" not to punish those who fail to measure up to those ideals.

The conversation inside the bookshop bounces around in history, philosophy, and theology, and finally returns to mercy. Paul directs everyone's attention to the Sermon on the Mount and the "beautiful impossibility" it portrays:

An end you can't by any means achieve, And yet can't turn your back on or ignore, That is the mystery you must accept.

It throws us by necessity onto mercy. "Mercy is only to the undeserving," Paul says, which includes all of us, in God's sight:

Here we all fail together, dwarfed and poor. Failure is failure, but success is failure. There is no better way of having it.

A door opens on its own to the store's cellar. Paul, who has had a cross painted on the cellar's ceiling, encourages Jonah to go down into its dark depths: "You must make your descent like everyone." It will require Jonah's abandonment and submission, essentially a death of self.

Jonah is hesitant. Finally he steps to the threshold, but the door slams in his face, knocking him to the floor. Lying there, collapsed and fading out, he confesses, "I think I may have got God wrong entirely." His own sense of justice, he says, "was about all there ever was to me." His last words are these: "Mercy on me for having thought I knew."

Kneeling over him, Paul speaks his own concluding words, affirming that "the best we have to offer" isn't enough. "Our very best, our lives laid down like Jonah's . . . may not be found acceptable in Heaven's sight."

The play closes with words from Keeper, who admits, "My failure is no different from Jonah's." He says they should lift Jonah's body and lay him "before the cross," just as Paul wanted. As the curtain falls, Keeper moves toward the prostrate Jonah and offers the play's final line:

Nothing can make injustice just but mercy.

Or as the New Testament says, "Mercy triumphs over judgment" (James 2:13).

(Taken from my book Surprised by Grace pg. 174-178)

February 6, 2012

Jehovah Knoweth None

I'm two weeks into a new sermon series on Galatians that I've entitled Free at Last. And I dare say that there is no other commentary on Galatians that is better or more important than Martin Luther's. Galatians, according to Luther, is the "Magna Carta of Christian Freedom." It is, he said, "my Katharina von Bora", referring to his beloved wife. Luther's commentary is not just a groundbreaking commentary on Galatians, it is one of the most important books ever written on the Gospel.

I'm two weeks into a new sermon series on Galatians that I've entitled Free at Last. And I dare say that there is no other commentary on Galatians that is better or more important than Martin Luther's. Galatians, according to Luther, is the "Magna Carta of Christian Freedom." It is, he said, "my Katharina von Bora", referring to his beloved wife. Luther's commentary is not just a groundbreaking commentary on Galatians, it is one of the most important books ever written on the Gospel.

One of my favorite sections is when he writes on how to answer the Accuser:

Paul does not say that works are objectionable, but to build one's hopes for righteousness on works is disastrous, for that makes Christ good for nothing. Let us bear this in mind when the devil accuses our conscience. When that dragon accuses us of having done no good at all, say to him, "You trouble me with the remembrance of my past sins; you remind me that I have done no good. But this does not bother me, because if I were to trust in my own good deeds, or despair because I have done no good deeds, Christ would profit me neither way. I am not going to make Him unprofitable to me. This I would do if I should presume to purchase for myself the favor of God by my good deeds or if I should despair of my salvation because of my sins."

This reminds me of my favorite hymn line:

Well may the accuser roar, of sins that I have done; I know them all and thousands more, Jehovah knoweth none!

January 31, 2012

What Kind Of A Pastor Do Sinners Need?

Sinclair Ferguson answers this question from his Marrow Controversy Lectures:

Sinclair Ferguson answers this question from his Marrow Controversy Lectures:

But when your people come and have been broken by sin and have fallen into temptation and are ashamed to confess the awful mess they have made of their life, it is not a Calvinistic pastor who has been sanctified by vinegar that they need. It is a pastor that has been mastered by the unconditional, free grace of God. It is a pastor from whom ironclad orthodoxy has been torn away and the whole armor of a gracious God has been placed upon his soul–the armor of one who would not break the bruised reed or quench the dimly burning wick.

You see, my friends, as we think together in these days about a Godly pastor we have to ask, what is a Godly pastor? A Godly pastor is one who is like God, who has a heart of free grace running after sinners. The Godly pastor is the one who sees the prodigal and runs and falls on his neck and weeps and kisses him and says, "This my son was dead, he was lost and now he is alive and found."

Pastors, when sinners are drowning, don't tell them to paddle harder and kick faster. Throw them the life-line of amazing grace.

January 27, 2012

Are Christians Totally Depraved?

Believe it or not, this is an important question. It's not simply a theological question. It's a theological question that has profound practical implications. Our answer will inevitably reveal our understanding of the gospel and reflect our understanding of sin and grace.

Believe it or not, this is an important question. It's not simply a theological question. It's a theological question that has profound practical implications. Our answer will inevitably reveal our understanding of the gospel and reflect our understanding of sin and grace.

First things first: what total depravity isn't.

Total depravity does not mean "utter depravity." Utter depravity means that someone is as bad as he/she can possibly be. Thankfully, God's restraining grace keeps even the worst of us from being utterly depraved. The worst people who have ever lived could've been worse. So, don't read "utter depravity" into "total depravity."

Well, if total depravity isn't utter depravity, then what is it? As understood and articulated by theologians for centuries, the idea of "total depravity" means more than one thing.

On the one hand, total depravity affirms that we are all born "dead in our trespasses and sins" (Ephesians 2:1-3; Colossians 2:13), with no spiritual capacity to incline ourselves Godward. We do not come into this world spiritually neutral; we come into this world spiritually dead. Therefore, we need much more than to reach out from our spiritual hospital bed and take medicine that God offers. We need to be raised from death to life. In this sense, total depravity means we are "totally unable" to go to God. We will not because we cannot, and we cannot because we're dead.

None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one. (Romans 3:10-12)

For the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God, for it does not submit to God's law; indeed, it cannot. Those who are in the flesh cannot please God. (Romans 8:7-8)

Salvation only happens when God comes to us.

When the Resurrection and the Life says "Lazarus, come forth", the rest of the story does not depend on Lazarus. He can drag his feet all the way–admittedly, a hell of a thing to do–but he rises, no matter what. He just plain does… Jesus came to raise the dead. The only qualification for the gift of the Gospel is to be dead. You don't have to be smart. You don't have to be good. You don't have to be wise. You don't have to be wonderful. You just have to be dead. That's it. (Robert Capon)

But once God regenerates us by his Spirit, unites us to Christ, raises us from the dead, and grants us status as adopted sons and daughters, is there any sense in which we can speak of Christian people being totally depraved?

Yes.

Theologians speak of total depravity, not only in terms of "total inability" to come to God on our own because we're spiritually dead, but also in terms of sin's effect: sin corrupts us in the "totality" of our being. Our minds are affected by sin. Our hearts are affected by sin. Our wills are affected by sin. Our bodies are affected by sin. This is at the heart of Paul's internal struggle that he articulates in Romans 7:

For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.

The painful struggle that Paul gives voice to arises from his condition as simul justus et peccator (simultaneously justified and sinful). He has been raised from the dead and is now alive to Christ, but remaining sin continues to plague him at every level and in every way.

Paul's testimony demonstrates that even after God saves us, there is no part of us that becomes sin free–we remain sinful and imperfect in all of our capacities, in the "totality" of our being. Even after God saves us, all of our thoughts, words, motives, deeds, and affections need the constant cleansing of Christ's blood and the forgiveness that comes our way for free. This is what J.C. Ryle was getting at when he wrote, "Even the best things we do have something in them to be pardoned."

While it is gloriously true for the Christian that there is nowhere Christ has not arrived by his Spirit, it is equally true that there is no part of any Christian in this life that is free of sin. Because of the totality of sins effect, therefore, we never outgrow our need for Christ's finished work on our behalf–we never graduate beyond our desperate need for Christ's righteousness and his strong and perfect blood-soaked plea "before the throne of God above."

The reason this is so important is because we will always be suspicious of grace ("yes grace, but…") until we realize our desperate need for it. Our dire need for God's grace doesn't get smaller after God saves us–in one sense, it actually gets bigger. Christian growth, says the Apostle Peter, is always "growth into grace", not away from it. Many Christians think that becoming sanctified means that we become stronger and stronger, more and more competent. And although we would never say it this way, we Christian's sometimes give the impression that sanctification is growth beyond our need for Jesus and his finished work for us: we needed Jesus a lot for justification; we need him less for sanctification.

The reason this is so important is because we will always be suspicious of grace ("yes grace, but…") until we realize our desperate need for it. Our dire need for God's grace doesn't get smaller after God saves us–in one sense, it actually gets bigger. Christian growth, says the Apostle Peter, is always "growth into grace", not away from it. Many Christians think that becoming sanctified means that we become stronger and stronger, more and more competent. And although we would never say it this way, we Christian's sometimes give the impression that sanctification is growth beyond our need for Jesus and his finished work for us: we needed Jesus a lot for justification; we need him less for sanctification.

The truth is, however, that Christian growth and progress involves coming to the realization of just how weak and incompetent we continue to be and how strong and competent Jesus continues to be for us. Spiritual maturity is not marked by our growing, independent fitness. Rather, it's marked by our growing dependence on Christ's fitness for us. Because we are daily sinners, we need God's daily distributions of free grace that come our way as a result of Christ's finished work. Christian growth involves believing and embracing the fact that, even as a Christian, you're worse than you think you are but that God's grace toward you in Christ is much bigger than you could ever imagine.

Because of total depravity, you and I were desperate for God's grace before we were saved. Because of total depravity, you and I remain desperate for God's grace even after we're saved.

Thankfully, though our sin reaches far, God's grace reaches infinitely farther.

January 23, 2012

What Is Grace?

What is grace? Grace is love that seeks you out when you have nothing to give in return. Grace is love coming at you that has nothing to do with you. Grace is being loved when you are unlovable. The cliché definition of grace is "unconditional love." It is a true cliché, for it is a good description of the thing…Let's go a little further, though.

Grace is a love that has nothing to do with you, the beloved. It has everything and only to do with the lover. Grace is irrational in the sense that it has nothing to do with weights and measures. It has nothing to do with my intrinsic qualities or so-called "gifts" (whatever they may be). It reflects a decision on the part of the giver (the one who loves) in relation to the receiver (the one who is loved) that negates any qualifications the receiver may personally hold…Grace is one-way love.

The one-way love of grace is the essence of any lasting transformation that takes place in human experience. You can find this out for yourself by taking a simple inventory of your own happiness, or the moments of happiness you have had. They have almost always had to do with some incident of love or belovedness that has come to you from someone outside yourself when you were down. You felt ugly or sinking in confidence and somebody complimented you, or helped you, or spoke a kind word to you. You were at the end of your rope and someone showed a little sympathy.

Some fear that grace-delivered, blood-bought, radical freedom will result in loveless license. But grace alone–redeeming, unconditional, one-way love–(not fear, not guilt, not shame) carries the power to compel heart-felt loyalty to the One who bought us (2 Corinthians 5:14).

January 18, 2012

What Does It Mean To Please God?

Rick Thomas writes an insightful piece entitled "The Danger of Trying to Please God." The counselor in this story sounds way too much like the way many of us preachers preach:

Sandra has struggled all her life with people pleasing. She said she could not remember a time when she was free from thinking about what others thought about her. The way she dresses, the car she drives, the technology she carries, and the house she owns are all controlled to some degree by what others think of her.

Sandra has struggled all her life with people pleasing. She said she could not remember a time when she was free from thinking about what others thought about her. The way she dresses, the car she drives, the technology she carries, and the house she owns are all controlled to some degree by what others think of her.

A Peek Into Her Life

She is fanatical about working out because of her keen awareness of what a "nice looking body" should look like. On a few occasions she has caught herself stretching the truth. She says she spins her stories because the real story doesn't seem as interesting. She is fearful of bringing a bag lunch to the office because everyone else goes out to a local restaurant to eat. She'd rather go into debt than feeling like the odd man out. She has a low-grade anger toward her boyfriend because he pressured her to have sex with him. She believed he would leave her if she didn't have sex. She needs to be loved by someone. Having a boyfriend is one of her ways of feeling significant.

Her biblical counselor quickly discerned that her problem was fear of man (Proverbs 29:25). The counselor told her she needed to be more concerned with pleasing God rather than others.

From there, the counselor laid out a plan of prayer, Bible study, and service oriented activities in order for her to practice a lifestyle of pleasing God. The mistake the counselor made was not carefully unpacking what pleasing God meant to an idolator like Sandra. Sandra is an idolator who has been living a performance-driven, people pleasing lifestyle. When she was told that she needed to be more willing to please God than man, it was not a difficult thing for her to do. People pleasing was what she knew best. Unfortunately, she was not told what pleases God so she did what she has always done–she ratcheted up her obedience.

Who Can Please God?

And a voice came from heaven, You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased. – Mark 1:11 (ESV)

Christ pleases God. Anything the Son does pleases the Father. Jesus came to do the will of the Father and He completed that task perfectly. The Father received the finished work of the Son and now a way has been made for us to please the Father by accepting the Son's work.

Without faith it is impossible to please him. – Hebrews 11:6 (ESV)

A Christian, who is living by faith in the works of the Son, is pleasing God. Pleasing God is not about what we do, but about believing in the only One who could authentically please the Father. Even on our best day, with our best works, we would not be acceptable to God.

We have all become like one who is unclean, and all our righteous deeds are like a polluted garment. – Isaiah 64:6 (ESV)

Sandra is a Christian. However, she is not seeking to please God by trusting (faith) in Him. She is still performing, but this time she is performing for the Father, hoping to get a good grade. Rather than accepting what is pleasing to God–the works of the Son–she tries to please Him by her obedience. For example, she says she feels more spiritual by going to church. She believes her activity for God gives her more of God. She feels more spiritual when she is doing. She also says that if she misses her prayer time, Bible reading, or a church meeting she feels less spiritual. She will read her 4 chapters each day, even while brushing her teeth so she can check it off.

Sandra is convinced that if she has her morning prayer time and things go well for her during the day, then she will partially contribute God's favor on her based on her prayer-time-obedience. As you might imagine, if she does not have her prayer time and things do not go well for her during the day, she feels as though her lack of prayer (disobedience) caused her day to go bad. Sometimes her friends affirm her theology of legalism when they observe her bad day and say, "You must not be prayed-up today."

Sandra is convinced that if she has her morning prayer time and things go well for her during the day, then she will partially contribute God's favor on her based on her prayer-time-obedience. As you might imagine, if she does not have her prayer time and things do not go well for her during the day, she feels as though her lack of prayer (disobedience) caused her day to go bad. Sometimes her friends affirm her theology of legalism when they observe her bad day and say, "You must not be prayed-up today."

As you can see, when her biblical counselor gave her a list of things to do in order to please God, Sandra initially was excited about the list. Any people pleasing, self-reliant, performance-driven person would be.

However, as time went by, she could not juggle her list of spiritual disciplines with the rest of her life. Eventually discouragement and depression set in–she could not keep up. From her perspective, God was not pleased with her–basing this on her poor performance. According to Sandra's functional theology she could control God's pleasure by what she did rather than what the Son did. Her understanding of Christ's work was limited. She believed the Gospel was for her salvation, while her obedience was the primary thing needed for her sanctification. Obedience is obviously hugely important to any Christian. However, the key is to make sure that your obedience is not an effort to please God, but a response to your faith in God.

This is only the first part of it. Read the whole thing here. What do you think?

January 14, 2012

Religion And The Gospel

A lot of attention has been paid to Jefferson Bethke's video Why I Hate Religion But Love Jesus. Jefferson is a great, humble, teachable brother who loves the gospel. But the response to his video has been varied. Many love it. Others hate it. And still others have raised a caution flag–uncomfortable with the way "religion" is often contrasted with the gospel.

A lot of attention has been paid to Jefferson Bethke's video Why I Hate Religion But Love Jesus. Jefferson is a great, humble, teachable brother who loves the gospel. But the response to his video has been varied. Many love it. Others hate it. And still others have raised a caution flag–uncomfortable with the way "religion" is often contrasted with the gospel.

Wary of the trend amongst younger evangelicals to justify their jettisoning of the institutional church and God's commands and theological traditions by saying "That's all religion and Jesus hates religion", is a point of contention for those who questioned the fruitfulness of Jefferson's video. If that's what people think when they hear the word "religion", then I understand the concern.

But, it does raise some important questions. For example, in the Bible, is the word "religion" always opposed to the gospel? Or, is the main idea of "religion" opposed to the main idea of the gospel? What about what people hear when they hear the word "religion"? Do they hear the word and understand something different than what the Bible says about the gospel? Good questions. Obviously words have their meaning in context and thankfully Jefferson provided context for his use of the word "religion" in the video by writing on his website:

[This is] a poem I wrote to highlight the difference between Jesus and false religion. In the scriptures Jesus received the most opposition from the most religious people of his day. At it's core Jesus' gospel and the good news of the Cross is in pure opposition to self-righteousness/self-justification. Religion is man centered, Jesus is God-centered. This poem highlights my journey to discover this truth.

Regardless of what you think about the video, I think that Jefferson's definition of "religion" above and Tim Keller's definition of "religion" below highlights an important distinction between "religion" and the gospel (a distinction that, ironically, even those who raised concerns about the video agree with).

Justifying the contrast between religion and the gospel, Tim Keller has pointed out that the Greek word for "religion" used in James 1 is used negatively in Colossians 2:18 where it describes false asceticism, fleshly works-righteousness, and also in Acts 26:5 where Paul speaks of his pre-Christian life in strict "religion." It is also used negatively in the Apocrypha to describe idol worship in Wis 14:18 and 27. So, according to Keller, the word certainly has enough negative connotations to use as a fair title for the category of works-righteousness. In the Old Testament the prophets are devastating in their criticism of empty ritual and religious observances designed to bribe and appease God rather then serving, trusting, and loving him. The word "religion" isn't used for this approach, but it's a good way to describe what the prophets are condemning.

Keller goes on to tease out this distinction with this helpful comparison list:

RELIGION: I obey-therefore I'm accepted

THE GOSPEL: I'm accepted-therefore I obey.

RELIGION: Motivation is based on fear and insecurity

THE GOSPEL: Motivation is based on grateful joy.

RELIGION: I obey God in order to get things from God

THE GOSPEL: I obey God to get to God-to delight and resemble Him.

RELIGION: When circumstances in my life go wrong, I am angry at God or my self, since I believe, like Job's friends that anyone who is good deserves a comfortable life

THE GOSPEL: When circumstances in my life go wrong, I struggle but I know all my punishment fell on Jesus and that while he may allow this for my training, he will exercise his Fatherly love within my trial.

RELIGION: When I am criticized I am furious or devastated because it is critical that I think of myself as a 'good person'. Threats to that self-image must be destroyed at all costs

THE GOSPEL: When I am criticized I struggle, but it is not critical for me to think of myself as a 'good person.' My identity is not built on my record or my performance but on God's love for me in Christ. I can take criticism.

RELIGION: My prayer life consists largely of petition and it only heats up when I am in a time of need. My main purpose in prayer is control of the environment

THE GOSPEL: My prayer life consists of generous stretches of praise and adoration. My main purpose is fellowship with Him.

RELIGION: My self-view swings between two poles. If and when I am living up to my standards, I feel confident, but then I am prone to be proud and unsympathetic to failing people. If and when I am not living up to standards, I feel insecure and inadequate. I'm not confident. I feel like a failure

THE GOSPEL: My self-view is not based on a view of my self as a moral achiever. In Christ I am "simul iustus et peccator"—simultaneously sinful and yet accepted in Christ. I am so bad he had to die for me and I am so loved he was glad to die for me. This leads me to deeper and deeper humility and confidence at the same time. Neither swaggering nor sniveling.

RELIGION: My identity and self-worth are based mainly on how hard I work. Or how moral I am, and so I must look down on those I perceive as lazy or immoral. I disdain and feel superior to 'the other

THE GOSPEL: My identity and self-worth are centered on the one who died for His enemies, who was excluded from the city for me. I am saved by sheer grace. So I can't look down on those who believe or practice something different from me. Only by grace I am what I am. I've no inner need to win arguments.

RELIGION: Since I look to my own pedigree or performance for my spiritual acceptability, my heart manufactures idols. It may be my talents, my moral record, my personal discipline, my social status, etc. I absolutely have to have them so they serve as my main hope, meaning, happiness, security, and significance, whatever I may say I believe about God

THE GOSPEL: I have many good things in my life—family, work, spiritual disciplines, etc. But none of these good things are ultimate things to me. None of them are things I absolutely have to have, so there is a limit to how much anxiety, bitterness, and despondency they can inflict on me when they are threatened and lost.

So let's not lose sight of the fact that, as defined by these two brothers, there is an antithetical relationship between religion (the burden of achieving rescue and right standing with God) and the gospel (the blessing of receiving rescue and a right standing with God in Christ alone).

One final thought: as I mentioned above, for a thousand different reasons people hear different things and draw different conclusions when they hear the same words (Cornelius Van Til). So, let's not forget as missionaries that if the gospel is ever going to reach people in our day it's going to have to be distinguished from religion (as described above) because "religion" is what most people outside the church think Christianity is all about—rules and standards and behavior and cleaning yourself up and politics and social causes and ascetic appeasement and self-salvation and climbing the "ladder", and a whole host of other things that Jefferson rightly points out.

Soli Deo Gloria!

January 13, 2012

The Subjective Power Of An Objective Gospel

I posted this article from my friend David Zahl (Mockingbird) back in June but read through it again this morning and was freshly edified. I hope you are too. His third paragraph is especially helpful in light of the discussion regarding the ultimate ground of our assurance (a subject I addressed here a few days ago).

The great Southern novelist Walker Percy once asked in his essay The Delta Factor, "Why does man feel so sad in the twentieth century? Why does man feel so bad in the very age when, more than in any other age, he has succeeded in satisfying his needs and making the world over for his own use?" The question remains a valid one, exposing how the subjective orientation of our culture tragically turns against itself. In other words, we are simultaneously more interested in self-fulfillment, and less fulfilled, than ever. That the Christian church, or "movement," would be a microcosm of this tendency should come as no surprise.

The great Southern novelist Walker Percy once asked in his essay The Delta Factor, "Why does man feel so sad in the twentieth century? Why does man feel so bad in the very age when, more than in any other age, he has succeeded in satisfying his needs and making the world over for his own use?" The question remains a valid one, exposing how the subjective orientation of our culture tragically turns against itself. In other words, we are simultaneously more interested in self-fulfillment, and less fulfilled, than ever. That the Christian church, or "movement," would be a microcosm of this tendency should come as no surprise.

American Christianity has historically placed a tremendous emphasis on faith as a means to happiness. Articulated most egregiously by figures such as 19th century revivalist Charles Finney, this sort of Christianity veers dangerously close to Pepsi Challenge territory, exemplified by well-meaning believers telling stories of how Jesus has made them better people: "I used to be like (unhappy, selfish, addicted, mean, lonely, fill in the blank), then I met Jesus, and now I'm (happy, generous, healthy, kind, etc)." The intention may be noble, to celebrate what God has done in our lives – an area where we understandably feel we can speak with authority, giving our message an added power – but sadly, it tends to backfire, especially when confronted with someone from another faith, for example Mormonism, who has had an equally if not more dramatic life-changing experience.

Make no mistake: Christ, by the power of the Holy Spirit will indeed do things within us and transform us. But that work, as profound as it may be, is not the Gospel. When the Gospel is associated with changed lives, it is immediately put at odds (and in competition with) other "spiritual products" and the "results" they have produced. The Gospel becomes only as reliable as the personal growth it may have produced, which we know – from experience (!) and from Scripture – is not always very reliable. We can wish our testimonies were sturdier, we can do our very best to keep up an illusion of inner and outer stability, but alas, an inescapable fact of human nature is that "my baby changes like the weather" (Smokey Robinson). This is not to say that our feelings and experiences need to be callously denied – of course not – they simply make lousy hitches for the Gospel plow.

Make no mistake: Christ, by the power of the Holy Spirit will indeed do things within us and transform us. But that work, as profound as it may be, is not the Gospel. When the Gospel is associated with changed lives, it is immediately put at odds (and in competition with) other "spiritual products" and the "results" they have produced. The Gospel becomes only as reliable as the personal growth it may have produced, which we know – from experience (!) and from Scripture – is not always very reliable. We can wish our testimonies were sturdier, we can do our very best to keep up an illusion of inner and outer stability, but alas, an inescapable fact of human nature is that "my baby changes like the weather" (Smokey Robinson). This is not to say that our feelings and experiences need to be callously denied – of course not – they simply make lousy hitches for the Gospel plow.

St. Paul actually taught that if we turn people into themselves, we turn them to despair and doubt (Romans 7:14-20, 8:1). Indeed, when the church places its emphasis on faith as a means of fulfillment, it automatically precludes its goal; it creates a situation where fulfillment becomes impossible. In secular terms, one might recall the psychotherapeutic maxim that, "happiness cannot be approached directly." Instead, the pursuit ushers in its exact opposite: despair. No wonder that a recent study by Lifeway Research found that 70% of young Protestant adults between the ages of 18-22 have stopped attending church. If you "accepted" Jesus into your heart years ago but besetting problems persist, and some circumstances even appear to get worse, if the Gospel is subjective, is it still true? Does it have the same power? That someone would walk away from the whole business is a foregone conclusion. For the remotely self-aware person, a Gospel based on personal sanctification is no Gospel at all. It produces refugees. Put another way, and to answer Mr. Percy's question, we are so sad in this century precisely because we have been so oriented toward and driven by a despair-inducing subjectivity. The Atlantic published a fantastic article on how this subject is playing out in the 'secular' sphere last month in their article "How The Cult of Self-Esteem is Ruining our Kids."

The Gospel of Jesus Christ (1 Cor 15:3-4) is good news, however, and good news for people with real problems. And it does tangibly address the subjective realities of suffering people – thank God – which is where most of us actually live. But it is helpful because it is true, not the other way around. One comes before the other. The Gospel is an objective word that has subjective power.

So what does this objective Gospel look like? Most importantly, it is outside of us: Jesus Christ died for our sins and that on the third day God raised him from the dead, so that we might become children of God, no longer subject to his just wrath and condemnation (1 Cor. 15:3-4). The Gospel points to Jesus and his work alone, that he died for our transgressions and was raised for our justification. It is specific and historic, having to do with what happened on a first-century cross in Roman-occupied Israel. To the question, "When were you saved?" we can answer with a hearty "2000 years ago, on a hill outside of Jerusalem" (John Warwick Montgomery via Rod Rosenbladt).

What, then, is the subjective power of this message? Firstly, we find that there is real, objective freedom, the kind that, yes, can be experienced subjectively. We are freed from having to worry about the legitimacy of experiences; our claims of self-improvement are no longer seen as a basis of our witness or faith. In other words, we are freed from ourselves, from the tumultuous ebb and flow of our inner lives and the outward circumstances; anyone in Christ will be saved despite those things. We can observe our own turmoil without identifying with it. We might even find that we have compassion for others who function similarly. These fluctuations, violent as they might be, do not ultimately define us. If anything, they tell us about our need for a savior.

What, then, is the subjective power of this message? Firstly, we find that there is real, objective freedom, the kind that, yes, can be experienced subjectively. We are freed from having to worry about the legitimacy of experiences; our claims of self-improvement are no longer seen as a basis of our witness or faith. In other words, we are freed from ourselves, from the tumultuous ebb and flow of our inner lives and the outward circumstances; anyone in Christ will be saved despite those things. We can observe our own turmoil without identifying with it. We might even find that we have compassion for others who function similarly. These fluctuations, violent as they might be, do not ultimately define us. If anything, they tell us about our need for a savior.

Secondly, this freedom gives us permission to confront and confess our pain. We can look our self-defeating and regressive tendencies in the eye for once. We no longer have to pretend to be anything other than what the Gospel tells us we are: hopeless sinners in need of mercy. Honesty and repentance go hand in hand – freedom puts us on our knees, where we belong. A subjective Gospel turns repentance into a frightening affair, evidence that God is far away from us. An objective Gospel provides the assurance that actually produces repentance, forging the pathway to the place where we find forgiveness and redemption. We can finally grasp hold of the truth that it is always better to be sorry than to be safe. The pastoral implications for marriage alone are staggering.

Finally, when it comes to our fellow sinners and sufferers, we witness to the love of God found in the cross which promises and proclaims redemption despite our feelings or how we are living. To the compulsive or addicted person, this makes all the difference.

An objective Gospel is all that we as Christians have to offer one another and the world. It is the only message that has any power to sustain us, and it is the only message that has the power to absolve us and keep us coming back to Christ, finding our hope, strength, and character when we are at our very best and worst. In other words, it is the only message that has the power to reach its subjects: you and me.

Amen.

January 9, 2012

Where Can I Find Assurance?

A month or so ago I made the point in this post that confidence in my transformation is not the source of my assurance. Rather, the source of my assurance comes from faith in Christ's substitution. Assurance never comes from looking at ourselves. It only comes as a consequence of looking to Christ.

A month or so ago I made the point in this post that confidence in my transformation is not the source of my assurance. Rather, the source of my assurance comes from faith in Christ's substitution. Assurance never comes from looking at ourselves. It only comes as a consequence of looking to Christ.

As a result, I had a few people raise this question: "But wait a minute…once God saves us and the Spirit begins his renewing work in our lives, shouldn't that work of inward renewal become a source of our assurance? Isn't that at least one way we can know we're right before God?"

At this point we need to be very clear regarding what we're talking about specifically when we talk about assurance of salvation.

To be sure, the sanctifying work of the Spirit in the life of the Christian bears fruit (Galatians 5:22-23). God grows us in the "grace and knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ." In Christ, we have died to sin and been raised to newness of life (Romans 6:4). And this new life shows itself in new affections, new appetites, new habits. We begin to love the things God loves and hate the things God hates. We begin to grow into our new, resurrected skin.

But when the Bible specifically speaks about assurance, it's addressing the question, "How then can man be in the right before God?" (Job 25:4). Assurance has to do, in other words, with the conscience's confidence in ultimate acquittal before God. When we are talking about assurance we are talking about final judgment–what God's ultimate verdict on us will be. Our assurance depends on how certain we are that God will say at the final judgment: "Not guilty!"

The Bible is plain that God requires moral perfection. It tells us unambiguously that God is holy and therefore cannot tolerate any hint of unholiness. Defects, blemishes, or stains–to the smallest degree–are unacceptable and deserving of God's wrath. And just in case I'm deluded enough to think that my Spirit-wrought moral improvement since I became a Christian is making the grade, Jesus (in the Sermon on the Mount) intensifies what God's required perfection entails: "Not only external actions but internal feelings and motives must be absolutely pure. Jesus condemns not only adultery but lust, not only murder but anger–promising the same judgment for both" (Gene Veith).

In Matthew 5-7, Jesus wants us to see that regardless of how well we think we're doing or how much better we're becoming, when "You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect" becomes the requirement and not "look how much I've grown over the years", we begin to realize that we don't have a leg to lean on when it comes to answering the question, "How can I stand righteous before God"? Our transformation, our purity, our growth in godliness, our moral advances and spiritual successes–Spirit-animated as it all may be–simply falls short of the sinlessness God demands. And since a "not guilty verdict" depends on sinlessness, assurance is ultimately contingent on perfection, not progress.

In Matthew 5-7, Jesus wants us to see that regardless of how well we think we're doing or how much better we're becoming, when "You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect" becomes the requirement and not "look how much I've grown over the years", we begin to realize that we don't have a leg to lean on when it comes to answering the question, "How can I stand righteous before God"? Our transformation, our purity, our growth in godliness, our moral advances and spiritual successes–Spirit-animated as it all may be–simply falls short of the sinlessness God demands. And since a "not guilty verdict" depends on sinlessness, assurance is ultimately contingent on perfection, not progress.

So, if God requires perfection and there is no definitive assurance without it (God isn't grading on a curve, after all), then what hope do I have, imperfect as I am?

The New Testament answer to this question is singular:

For in the gospel a righteousness from God is revealed, a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: "The righteous will live by faith." (Romans 1:17)

For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith. (Romans 3:23-25)

And to the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness. (Romans 4:5)

The conscience is given assurance only as living faith is created by the Spirit through the Gospel announcement that God justifies the ungodly. The righteousness we need comes from God "through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe." (Romans 3:22)

The life we live, we live by faith in "the Son of God who loved me and gave himself for me" (Galatians 2:20). So faith is the only touchstone for assurance–the God-gifted miracle of believing the impossible reality that God forgives me and loves me because of what Christ accomplished on my behalf. Assurance happens when the God-given, Spirit-wrought gift of faith enables me to believe that I am forever pardoned, that Christ's righteousness is counted as my own, that in Christ God does not count my sins against me (2 Corinthians 5:19). We are justified (reckoned righteous) by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. God's demand for moral perfection has been satisfied by Christ for us (Matthew 5:17). Therefore, assurance can never be found by my looking in. It can only happen by faith–believing in him who was "delivered over to death for our sins and was raised to life for our justification." (Romans 4:25)

The life we live, we live by faith in "the Son of God who loved me and gave himself for me" (Galatians 2:20). So faith is the only touchstone for assurance–the God-gifted miracle of believing the impossible reality that God forgives me and loves me because of what Christ accomplished on my behalf. Assurance happens when the God-given, Spirit-wrought gift of faith enables me to believe that I am forever pardoned, that Christ's righteousness is counted as my own, that in Christ God does not count my sins against me (2 Corinthians 5:19). We are justified (reckoned righteous) by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. God's demand for moral perfection has been satisfied by Christ for us (Matthew 5:17). Therefore, assurance can never be found by my looking in. It can only happen by faith–believing in him who was "delivered over to death for our sins and was raised to life for our justification." (Romans 4:25)

Martyn Lloyd-Jones is helpful here:

We can put it this way: the man who has faith is the man who is no longer looking at himself and no longer looking to himself. He no longer looks at anything he once was. He does not look at what he is now. He does not even look at what he hopes to be as the result of his own efforts. He looks entirely to the Lord Jesus Christ and His finished work, and rests on that alone. He has ceased to say, "Ah yes, I used to commit terrible sins but I have done this and that." He stops saying that. If he goes on saying that, he has not got faith. Faith speaks in an entirely different manner and makes a man say, "Yes I have sinned grievously, I have lived a life of sin, yet I know that I am a child of God because I am not resting on any righteousness of my own; my righteousness is in Jesus Christ and God has put that to my account."

True assurance, in other words, is based not on some word or work from inside us, but on the word of the gospel which comes from outside us and convinces us of what Jesus has done. Our assurance is anchored in the love and grace of God expressed in the glorious exchange: our sin for his righteousness. And since our faith is always weak and wavering, we need to be reminded of this good news all the time as it is communicated through preaching and confirmed in the sacraments.

In the February 2003 issue of New Horizons, Peter Jensen writes:

The gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ says that the ground of our assurance is our justification. In Romans 5:1, Paul writes that "since we have been justified through faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ." Faith in Jesus Christ (which is itself a gift from God) has given us access "into this grace in which we now stand" (vs. 2). We do not stand in any experience which we have had, we do not stand in any progress which we have made, we do not stand in our success in the battle against sin. We stand in the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which he has justified us.

What we have to keep remembering is that "before the throne of God above" we are (and in ourselves always will be) imperfect–so, no assurance by looking at ourselves. But, "before the throne of God above, I have a strong and perfect plea"–and that strong plea is not my imperfect transformation by grace, it is not my love for God and neighbor, it's not how much I've grown over the years. That strong and perfect plea is Jesus Christ–sola!

Because the sinless Savior died

My sinful soul is counted free.

For God the just is satisfied

To look on Him and pardon me.

So, "when Satan tempts me to despair and tells me of the guilt within", if I look in I'm in big trouble. But, if "upward I look and see him there, who made an end of all my sin", then by the miracle of faith, I can say to the accuser who roars of sins that I have done, "I know them all and thousands more, Jehovah knoweth none."

It is for this reason (and in this context) that I told the story of the old pastor who, on his deathbed, said to his wife that he was certain he was going to heaven because he couldn't remember one truly good work he had ever done. His assurance was grounded by faith where only true assurance can ever be grounded: Christ's perfect work for us, not our imperfect work for him.

Rest assured: Before God, the righteousness of Christ is all we need; before God, the righteousness of Christ is all we have.

January 5, 2012

Might As Well Face It, You're Addicted To Law

I'll never forget hearing Dr. Doug Kelly (one of my theology professors in seminary) saying in class, "If you want to make people mad, preach law. If you want to make them really, really mad preach grace." I didn't know what he meant then. But I do now.

I'll never forget hearing Dr. Doug Kelly (one of my theology professors in seminary) saying in class, "If you want to make people mad, preach law. If you want to make them really, really mad preach grace." I didn't know what he meant then. But I do now.

The law offends us because it tells us what to do–and we hate anyone telling us what to do, most of the time. But, ironically, grace offends us even more because it tells us that there's nothing we can do, that everything has already been done. And if there's something we hate more than being told what to do, it's being told that we can't do anything, that we can't earn anything–that we're helpless, weak, and needy.

The law, at least, assures us that we determine our own destiny.

The law does promise life to me,

If my obedience perfect be. (Ralph Erskine)

This we understand. And we like it. We like it because we maintain control–the outcome of our life remains in our hands. Give me three steps to a happy marriage and I can guarantee myself a happy marriage if I follow the three steps. If we can do certain things, meet certain standards, and become a certain way, we'll make it. Law seems safe because "it breeds a sense of manageability." It keeps life formulaic and predictable. It keeps earning-power in our camp.

The logic of law makes sense.

The logic of grace, on the other hand, doesn't.

Grace is thickly counter-intuitive. It feels risky and unfair. It turns everything that makes sense to us upside-down. Like Job's friends, we naturally conclude that good people get good stuff and bad people get bad stuff. The idea that bad people get good stuff seems irrational and wrongheaded on every level. It offends our deepest sense of justice and rightness.

Grace is not rational…The gospel of grace throws our glory train off its tracks. Instead of calculating, mastering, and determining, we find ourselves completely helpless, left with no option but to fall into the everlasting arms of the God who could consume us in his wrath but instead embraces us in his Son. (Mike Horton)

So, it doesn't surprise me at all when I hear people react to grace with suspicion and doubt. It doesn't surprise me that when people talk about grace, I hear lots of "buts and brakes", conditions and qualifications. That's just the flesh fighting for its life, after all. As Walter Marshall says in his book The Gospel Mystery of Sanctification, "By nature, you are completely addicted to a legal method of salvation. Even after you become a Christian by believing the Gospel, your heart is still addicted to salvation by works…You find it hard to believe that you should get any blessing before you work for it."

Because we are natural born do-it-yourselfers–God-wannabes–(and have been since Genesis 3), the vitriol reaction to unconditional grace is understandable. Grace generates panic because it wrestles both control and glory out of our hands. This means that the part of you that gets angry and upset and mean and defensive and slanderous and critical and skeptical and feisty when you hear about grace is the very part of you that needs to be reckoned dead. That's where mortification begins–it begins with that part of us that hates grace.

But while I'm not surprised when I hear venomous rejoinders to grace (the flesh is always resistant to "It is finished"), I am saddened when the very pack of people that God has unconditionally saved and continues to sustain by his free grace are the very ones who push back most violently against it. Some professing Christians sound like ungrateful children who can't stop biting the very hand that feeds them. It amazes me that you will hear great concern from inside the church about "too much grace" but rarely will you ever hear great concern from inside the church about "too many rules." Why? Because we are by nature glory-hoarding, self-centered control freaks. That's why.

But while I'm not surprised when I hear venomous rejoinders to grace (the flesh is always resistant to "It is finished"), I am saddened when the very pack of people that God has unconditionally saved and continues to sustain by his free grace are the very ones who push back most violently against it. Some professing Christians sound like ungrateful children who can't stop biting the very hand that feeds them. It amazes me that you will hear great concern from inside the church about "too much grace" but rarely will you ever hear great concern from inside the church about "too many rules." Why? Because we are by nature glory-hoarding, self-centered control freaks. That's why.

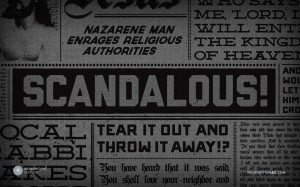

It's high time for the church to honor God by embracing sola gratia anew–the "high-octane grace that takes our conscience by the scruff of the neck and breathes new life into us with a pardon so scandalous that we cannot help but be changed…For many of us the time has come to abandon once and for all our play-it-safe, toe-dabbling Christianity and dive in" (Dane Ortlund). It is time, as Robert Farrar Capon put it, to get drunk on grace. Two hundred-proof, defiant grace.

It's scandalous and scary, unnatural and undomesticated…but it's the only thing that can set us free and light the church on fire.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers