Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 15

July 19, 2013

Is Your Life Defined By A Ladder Or A Cross?

Believe it or not, the familiar story of the Tower of Babel teaches us more than we ever thought about the nature of sin, God’s grace, and the reality of descending one-way love. It’s the entire message of the Bible in a nutshell:

Believe it or not, the familiar story of the Tower of Babel teaches us more than we ever thought about the nature of sin, God’s grace, and the reality of descending one-way love. It’s the entire message of the Bible in a nutshell:

There are things in life that can tell us what kind of person you are: chunky peanut butter, or smooth? Regular cola, or diet? It seems to me that the same is true when it comes to reading the Bible. Do you read the Bible as a helpful tool in your climb up toward moral betterment or as the story of God coming down to broken, sinful people?

In a very real way, our lives are defined by how we answer that question. Specifically, our lives are defined either by a cross or by a ladder. The ladder symbolizes our ascension—our effort to “go up.” The cross symbolizes God’s descension—his coming down.

There is no better story in the Old Testament, or perhaps the whole Bible, for depicting the difference between the ladder-defined life and the cross-defined life than that of the Tower of Babel.

Read the rest here.

July 16, 2013

What Is Grace?

The definition I give for grace in my forthcoming book, One-Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World, comes from Paul Zahl. He writes:

Grace is love that seeks you out when you have nothing to give in return. Grace is love coming at you that has nothing to do with you. Grace is being loved when you are unlovable…. The cliché definition of grace is “unconditional love.” It is a true cliché, for it is a good description of the thing. Let’s go a little further, though. Grace is a love that has nothing to do with you, the beloved. It has everything and only to do with the lover. Grace is irrational in the sense that it has nothing to do with weights and measures. It has nothing to do with my intrinsic qualities or so-called “gifts” (whatever they may be). It reflects a decision on the part of the giver, the one who loves, in relation to the receiver, the one who is loved, that negates any qualifications the receiver may personally hold…. Grace is one-way love.

Grace doesn’t make demands. It just gives. And from our vantage point, it always gives to the wrong person. We see this over and over again in the Gospels: Jesus is always giving to the wrong people—prostitutes, tax collectors, half-breeds. The most extravagant sinners of Jesus’s day receive his most compassionate welcome. Grace is a divine vulgarity that stands caution on its head. It refuses to play it safe and lay it up. Grace is recklessly generous, uncomfortably promiscuous. It doesn’t use sticks, carrots, or time cards. It doesn’t keep score. As Robert Capon puts it, “Grace works without requiring anything on our part. It’s not expensive. It’s not even cheap. It’s free.” It refuses to be controlled by our innate sense of fairness, reciprocity, and evenhandedness. It defies logic. It has nothing to do with earning, merit, or deservedness. It is opposed to what is owed. It doesn’t expect a return on investments. Grace is unconditional acceptance given to an undeserving person by an unobligated giver.

It is one-way love.

July 12, 2013

We Don’t Find Grace, Grace Finds Us

I’m not sure I’ll ever fully understand why some Christians get mad when we say that the ultimate hero in the Bible is not Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Paul, etc….but Jesus. There seems to be an unhealthy attraction to find someone in the Bible other than Jesus who is ultimately worthy of our attention and emulation–someone to look up to, copy, respect. There is a strange impulse in many to protect Bible characters and to use them as inspiration…as if sanctification happens as a result of emulation.

I’m not sure I’ll ever fully understand why some Christians get mad when we say that the ultimate hero in the Bible is not Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Paul, etc….but Jesus. There seems to be an unhealthy attraction to find someone in the Bible other than Jesus who is ultimately worthy of our attention and emulation–someone to look up to, copy, respect. There is a strange impulse in many to protect Bible characters and to use them as inspiration…as if sanctification happens as a result of emulation.

Since Genesis 3 we have been addicted to setting our sights on something, someone, smaller than Jesus. Why? It’s not that there aren’t things about certain people in the Bible that aren’t admirable. Of course there are. We quickly forget, however, that whatever we see in them that is commendable is a reflection of the gift of righteousness they’ve received from God–it is nothing about them in and of itself.

This impulse to protect Bible characters and make them the “end” of the story happens almost universally with the story of Noah.

Noah is often presented to us as the first character in the Bible really worthy of emulation.

Adam? Sinner.

Eve? Sinner.

Cain? Big sinner!

But Noah? Finally, someone we can set our sights on, someone we can shape our lives after, right?

This is why so many Sunday School lessons handle the story of Noah like this: “Remember, you can believe what God says! Just like Noah! You too can stand up to unrighteousness and wickedness in our world like Noah did. Don’t be like the bad people who mocked Noah. Be like Noah.”

I understand why many would read this account in this way. After all, doesn’t the Bible say that Noah “was a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time, and he walked faithfully with God” (Genesis 6:9)? Pretty incontrovertible, right?

Not so fast.

Read the rest here.

July 10, 2013

The Attraction Of Legal Preaching

Scott Clark has posted an important, creative, and compelling piece on the attraction of “legal preaching.” He writes:

Scott Clark has posted an important, creative, and compelling piece on the attraction of “legal preaching.” He writes:

A legal preacher is a preacher who majors in the law to the neglect of the gospel. In practice, he preaches nothing but law. He thinks that mentioning Jesus periodically or even regularly means that he’s not a legal preacher and he can’t imagine that people are concerned about the tenor of his preaching because he doesn’t see anything wrong with it. It’s the sort of preaching he heard as a young man and it’s the sort of preaching he heard in seminary and it’s the sort of preaching he admires in other preachers.

He turns every passage into a law, because he doesn’t know any other way to read the Scripture and he doesn’t know any other way to preach. He preaches the law and he doesn’t even know he’s doing he it, even when, in his mind, he’s preaching the gospel. When he finds a bit of good news in his passage, he doesn’t end with that because he doesn’t want his people to get the idea that there are no obligations to the Christian life.

He’s heard talk about a distinction between law and gospel but he’s pretty sure that’s a Lutheran way to think and talk and beside, he never heard that when he went to seminary and he went to a good school where, were it important, he would have heard about it. He’s suspicious of the fellows who do talk about law and gospel. They don’t seem to be nearly as interested in sanctification and obedience as they should be. Certainly those fellows aren’t as interested in it as he is. He suspects that those fellows are just lazy.

Read the rest of this super important post here.

July 2, 2013

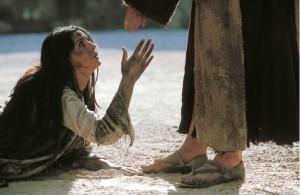

God Threw A Stone

As I’ve said before, God speaks two words to the world. People have called them many things: Law and Gospel, Judgment and Love, Critique and Grace, and so on. In essence, though, it’s pretty simple: first, God gives us bad news (about us), and then, God gives us Good News (about Jesus).

This is perhaps most clearly seen in another incredibly well-known (and incredibly misunderstood) passage of Scripture: Jesus’ interaction with the woman caught in the act of adultery.

This is perhaps most clearly seen in another incredibly well-known (and incredibly misunderstood) passage of Scripture: Jesus’ interaction with the woman caught in the act of adultery.

The scribes and Pharisees catch a woman in the act of adultery, and drag her before Jesus. Can you imagine a woman who ever felt more shame than this one? Literally caught in the act of adultery? Unfathomable. They tell Jesus of her infraction, and remind him that the law of Moses says such women should be stoned. Then they issue a challenge: “What do you say?” They’re trying to trick Jesus into admitting what they suspect: that he’s “soft” on the Law.

Boy, were they wrong.

Read the rest here.

June 28, 2013

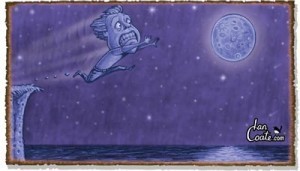

All You Have To Do Is Jump To The Moon

J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted that “A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace.” The reason this seems so counter-intuitive is because most people think that those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God’s law (hence, the regular charge of antinomianism). Others think that those with a high view of the law are the legalists. But Machen makes the compelling point that it’s a low view of the law that produces legalism because a low view of the law causes us to conclude that we can do it–the bar is low enough for us to jump over. A low view of the law makes us think that the standards are attainable, the goals are reachable, the demands are doable.

J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted that “A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace.” The reason this seems so counter-intuitive is because most people think that those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God’s law (hence, the regular charge of antinomianism). Others think that those with a high view of the law are the legalists. But Machen makes the compelling point that it’s a low view of the law that produces legalism because a low view of the law causes us to conclude that we can do it–the bar is low enough for us to jump over. A low view of the law makes us think that the standards are attainable, the goals are reachable, the demands are doable.

I love this illustration from Max Lucado’s book, In the Grip of Grace, on how judgmental instincts are anchored in a low view of God’s law:

Judging others is the quick and easy way to feel good about ourselves. A convenience-store-ego-boost. Standing next to all the Mussolinis and Hitlers and Dahmers of the world, we boast, “Look God, compared to them I’m not that bad.”

But that’s the problem. God doesn’t compare us to them. They aren’t the standard. God is. And compared to him, Paul will argue, “There is no one does anything good” (Rom. 3:12).

Suppose God simplified matters and reduced the Bible to one command: “Thou must jump so high in the air that you touch the moon.” No need to love your neighbor or pray or follow Jesus; just touch the moon by virtue of a jump, and you’ll be saved.

We’d never make it. There may be a few who jump three or four feet, even fewer who jump five or six; but compared to the distance we have to go, no one gets very far. Though you may jump six inches higher than I do, it’s scarcely reason to boast.

Now, God hasn’t called us to touch the moon, but he might as well have. He said, “You must be perfect, just as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). None of us can meet God’s standard. As a result, none of us deserves to don the robe and stand behind the bench and judge others. Why? We aren’t good enough. Dahmer may jump six inches and you may jump six feet, but compared to the 230,000 miles that remain, who can boast?

The thought of it is almost comical. We who jump three feet look at the fellow who jumped one inch and say, “What a lousy jump.” Why do we engage in such accusations? It’s a ploy. As long as I am thinking of your weaknesses, then I don’t have to think about my own. As long as I am looking at your puny jump, then I don’t have to be honest about my own. I’m like the man who went to see the psychiatrist with a turtle on his head and a strip of bacon dangling from each ear and said, “I’m here to talk to you about my brother.”

June 24, 2013

Who Is The Good Samaritan?

The parable of the Good Samaritan may be the most well-known and the most misunderstood parable Jesus ever told:

The parable of the Good Samaritan may be the most well-known and the most misunderstood parable Jesus ever told:

For every good story in the Bible there’s a bad children’s song. This is the one I remember for the Good Samaritan:

The man who stopped to help, right when he saw the need; he was such a good, good neighbor, a good example for me.

On the surface, this little ditty may seem harmless. The problem, however, is that Jesus wants us to identify with every person in the parable except the good Samaritan. He reserves that role for himself.

Read the rest here.

June 19, 2013

A Picture Of Grace

It’s impossible for someone to embrace grace with no “buts and brakes” until they’ve come to terms with their own radical helplessness. Every person I’ve ever met who has crashed and burned and, as a result, come to grips with the reality of their own powerlessness, has taught me something about God’s grace that I would’ve never known otherwise.

This amazing testimony by my dear friend, Chris Crawford, is proof that grace alone has the power to change and transform.

Pictures of Grace – Chris Crawford from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

June 14, 2013

The Mathematics of Grace

I love the way Philip Yancey describes the discrepancy between our instincts and God’s instincts in his book What’s So Amazing About Grace?

I love the way Philip Yancey describes the discrepancy between our instincts and God’s instincts in his book What’s So Amazing About Grace?

By instinct I feel I must do something in order to be accepted. Grace sounds a startling note of contradiction, of liberation, and every day I must pray anew for the ability to hear its message.

Eugene Peterson draws a contrast between Augustine and Pelagius, two fourth-century theological opponents. Pelagius was urbane, courteous, convincing, and liked by everyone. Augustine squandered away his youth in immorality, had a strange relationship with his mother, and made many enemies. Yet Augustine started from God’s grace and got it right, whereas Pelagius started from human effort and got it wrong. Augustine passionately pursued God; Pelagius methodically worked to please God. Peterson goes on to say that Christians tend to be Augustinian in theory but Pelagian in practice. They work obsessively to please other people and even God.

Each year in spring, I fall victim to what the sports announcers diagnose as “March Madness.” I cannot resist the temptation to tune in to the final basketball game, in which the sole survivors of a sixty-four-team tournament meet for the NCAA championship. That most important game always seems to come down to one eighteen-year-old kid standing on a freethrow line with one second left on the clock. He dribbles nervously. If he misses these two foul shots, he knows, he will be the goat of his campus, the goat of his state. Twenty years from now he’ll be in counseling, reliving this moment. If he makes these shots, he’ll be a hero. His picture will be on the front page. He could probably run for governor. He takes another dribble and the other team calls time, to rattle him. He stands on the sideline, weighing his entire future. Everything depends on him. His teammates pat him encouragingly, but say nothing.

One year, I remember, I left the room to answer a phone call just as the kid was setting himself to shoot. Worry lines creased his forehead. He was biting his lower lip. His left leg quivered at the knee. Twenty thousand fans were yelling, waving banners and handkerchiefs to distract him. The phone call took longer than expected, and when I returned I saw a new sight. This same kid, his hair drenched with Gatorade, was now riding atop the shoulders of his teammates, cutting the cords of a basketball net. He had not a care in the world. His grin filled the entire screen.

Those two freeze-frames—the same kid crouching at the free throw line and then celebrating on his friends’ shoulders—came to symbolize for me the difference between ungrace and grace.

The world runs by ungrace. Everything depends on what I do. I have to make the shot.

Jesus calls us to another way, one that depends not on our performance but his own. We do not have to achieve but merely follow. He has already earned for us the costly victory of God’s acceptance.

June 10, 2013

Reading The Bible Narcissistically

We often read the Bible as if it were fundamentally about us: our improvement, our life, our triumph, our victory, our faith, our holiness, our godliness. We treat it like a book of timeless principles that will give us our best life now if we simply apply those principles. We treat it, in other words, like it’s a heaven-sent self-help manual. But by looking at the Bible as if it were fundamentally about us, we totally miss the Point–like the two on the road to Emmaus. As Luke 24 shows, it’s possible to read the Bible, study the Bible, and memorize large portions of the Bible, while missing the whole point of the Bible. It’s entirely possible, in other words, to read the stories and miss the Story. In fact, unless we go to the Bible to see Jesus and his work for us, even our devout Bible reading can become fuel for our own narcissistic self-improvement plans, the place we go for the help we need to “conquer today’s challenges and take control of our lives.”

We often read the Bible as if it were fundamentally about us: our improvement, our life, our triumph, our victory, our faith, our holiness, our godliness. We treat it like a book of timeless principles that will give us our best life now if we simply apply those principles. We treat it, in other words, like it’s a heaven-sent self-help manual. But by looking at the Bible as if it were fundamentally about us, we totally miss the Point–like the two on the road to Emmaus. As Luke 24 shows, it’s possible to read the Bible, study the Bible, and memorize large portions of the Bible, while missing the whole point of the Bible. It’s entirely possible, in other words, to read the stories and miss the Story. In fact, unless we go to the Bible to see Jesus and his work for us, even our devout Bible reading can become fuel for our own narcissistic self-improvement plans, the place we go for the help we need to “conquer today’s challenges and take control of our lives.”

Contrary to popular assumptions, the Bible is not a record of the blessed good, but rather the blessed bad. That’s not a typo. The Bible is a record of the blessed bad. The Bible is not a witness to the best people making it up to God; it’s a witness to God making it down to the worst people. Far from being a book full of moral heroes to emulate, what we discover is that the so-called heroes in the Bible are not really heroes at all. They fall and fail, they make huge mistakes, they get afraid, their selfish, deceptive, egotistical, and unreliable. The Bible is one long story of God meeting our rebellion with his rescue; our sin with his salvation; our failure with his favor; our guilt with his grace; our badness with his goodness.

So, if we read the Bible asking first, “What would Jesus do?” instead of asking “What has Jesus done” we’ll miss the good news that alone can set us free.

As I’ve said before, the overwhelming focus of the Bible is not the work of the redeemed but the work of the Redeemer. Which means that the Bible is not first a recipe book for Christian living, but a revelation book of Jesus who is the answer to our unchristian living.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers