Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 17

April 23, 2013

Sufferers Comforting Sufferers

Over at Mockingbird, my good friend R-J Heijmen has a great post regarding why preachers of the Gospel always talk about sin:

Over at Mockingbird, my good friend R-J Heijmen has a great post regarding why preachers of the Gospel always talk about sin:

The Gospel preacher [recognizes] that life is often (perhaps mostly) hard, and that as much as we might crave a word of optimism, a little fuel for the part of us that longs to live in blissful ignorance (or denial), what we really need is not to have our humanity built up, but rather put to death. True hope – hope in God and his unbreakable love for us in Jesus Christ – comes only when we let go of our false hopes, and this happens only in the crucible of real, hard, life. In this view, church ceases to be a venue for fairy tales and bedtime stories, but rather a haven for sufferers. Church is the place where we come together to hear and tell the truth about our lives, our sin, and to receive grace and mercy. As Luther poignantly said, “If the mercy is true, you must therefore bear a true, not an imaginary sin. God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners.”

You can read the whole thing here.

April 19, 2013

Grace And The Summer Of George

In October, my book One-Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World will be released. Below is an excerpt of the book that was originally posted over at Mockingbird.

In October, my book One-Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World will be released. Below is an excerpt of the book that was originally posted over at Mockingbird.

For many Americans of a certain age, the college admissions process is an oppressive and extraordinarily stressful area of life. It is performancism writ very, very large. One’s entire worth and value as a person is boiled down to a short transcript and application, which is then judged according to a stringent and ever-escalating set of standards. High-school seniors are called upon to justify themselves according to their achievements and interests, and as the top schools have gotten more and more competitive, so has the pressure under which our top students place themselves. Watching the students at our church go through it, not to mention my own kids, it’s hard not to sympathize. They feel that their entire lives are hanging in the balance, that where they go to school will dictate their happiness for years to come. It isn’t, of course, but that’s usually beside the point.

A number of years ago, I watched as two best friends, Wayne and Dave, applied for early admission at the same college. That December, Wayne was accepted and Dave was deferred. The next four months, during which Dave waited for the final ruling, looked very different—and very similar—for each of them. They both took basically the same classes and had the same homework load. They spent time with many of the same people socially. But there were also a couple of key differences. No longer under the watchful eye of the all-important transcript, Wayne decided to branch out in his extracurricular activities. He started a band and got into rock-climbing. He even pioneered a program teaching underprivileged kids in the community how to climb. The program still exists, more than ten years later. Meanwhile, Dave got involved in a bunch of extracurriculars that he had never been involved with before, stuff that he thought might boost his chances at getting into his dream college.

By the end of the semester, Dave was exhausted, and Wayne was full of energy. Although Dave did well and kept up his GPA, Wayne got the best grades of his high school career! Freed from having to play it safe, he wrote his papers about topics he was genuinely interested in, rather than the ones he thought the teacher would appreciate, and it showed on the page. Their paths may not have looked very different to the outside eye, but one of these guys was carrying a burden of expectation and one wasn’t. No wonder it felt like such a slog.

The fruit of assurance in Wayne’s life was not laziness but creativity, charity and fun. Set free from the imperative to perform, his performance shot off the charts. Set free from having to earn his future, he enjoyed his present. Set free from the burden of self-focus, he was inspired to serve others—and without being told he needed to do so! This is very similar to the dynamic we see with many of those that Jesus heals.

The message of God’s one-way love for sinners naturally meets resistance from law-locked hearts. It produces objections in those who are wired for earning and deserving, which is all of us. Sometimes these objections are rationalized forms of the emotional offense taken by creatures addicted to their own sense of control. When our sense of pride is attacked, it defends. Sometimes these objections are projections of fear about what “might” happen if people actually believed the message. Sometimes the objections to grace are simply honest rejoinders to a word that can be very hard to swallow. Two of the most frequent objections I encounter—and I encounter them a lot—are that grace makes people lazy, and grace gives people license to indulge their self-absorption, rather than serve their neighbor.

If it is true that Jesus paid it all, that “it is finished”, that my value, worth, security, freedom, justification, and so on is forever fixed, then why do anything? Doesn’t grace undercut ambition? Doesn’t the gospel weaken effort? If we are truly let off the hook, what is to stop us from ending up like George Costanza in the “Summer of George” episode of the sitcom Seinfeld, who receives an unexpected severance package and vows to take full advantage of his freedom only to sit around in sweatpants, watching TV, reading comic books, and eating “a big hunk of cheese like it’s an apple”? Or, as Billy Corgan (lead singer of Smashing Pumpkins) once said, “If practice makes perfect and no one’s perfect, then why practice?” Understandable question.

If it is true that Jesus paid it all, that “it is finished”, that my value, worth, security, freedom, justification, and so on is forever fixed, then why do anything? Doesn’t grace undercut ambition? Doesn’t the gospel weaken effort? If we are truly let off the hook, what is to stop us from ending up like George Costanza in the “Summer of George” episode of the sitcom Seinfeld, who receives an unexpected severance package and vows to take full advantage of his freedom only to sit around in sweatpants, watching TV, reading comic books, and eating “a big hunk of cheese like it’s an apple”? Or, as Billy Corgan (lead singer of Smashing Pumpkins) once said, “If practice makes perfect and no one’s perfect, then why practice?” Understandable question.

To be perfectly honest, in the short term, this message often does inspire the kind of sighs of relief and extended breathers that look a whole lot like doing nothing. But if a person can be given the space to bask in the good news for a while (without being hammered with fresh injunctions), we just as often find that the gospel of grace, in the long run, actually empowers risk-taking effort and neighbor-embracing love. It doesn’t have to, of course, which is precisely why it often does. Think about it: what prevents us from taking great risks most of the time is the fear that if we don’t succeed, we will lose out on something we need in order to be happy. And so we live life playing our cards close to the chest…relationally, vocationally, spiritually. We measure our investments carefully because we need a return—we are afraid to give because it might not work out and we need it to work out.

The refrain that applies here is the same one that always applies: everything we need, we already possess in Christ. This means that the “what if” has been taken out of the equation. We can take absurd risks, push harder, go farther, and leave it all on the field without fear—and have fun doing so. We can give with reckless abandon because we no longer need to ensure a return of success, love, meaning, validation, and approval. We can invest freely and forcefully because we’ve been freely and forcefully invested in. Perhaps this is part of why rates of charitable giving are so much higher in places where people go to church. Perhaps not.

The Gospel breaks the chains of reciprocity and the circular exchange. Since there nothing we ultimately need from one another, we are free to do everything for one another. Spend our lives giving instead of taking, going to the back instead of getting to the front, sacrificing ourselves for others instead of sacrificing others for ourselves. The gospel alone liberates us to live a life of scandalous generosity, unrestrained sacrifice, uncommon valor, and unbounded courage.

This is the difference between approaching all of life from salvation and approaching all of life for salvation; it’s the difference between approaching life from our acceptance, and not for our acceptance; from love not for love. The acceptance letter has arrived and it cannot be rescinded, thank God.

I remember reading an article about Netflix a few years ago, the wildly successful video rental and streaming company, that points to what we are talking about here. Netflix, it turns out, has no official vacation policy. They let their employees take as much time off as they want, whenever they want, as long as the job is getting done. The article quoted Netflix’s vice president for corporate communication, Steve Swasey, as saying, “Ever more companies are realizing that autonomy isn’t the opposite of accountability – it’s the pathway to it. Rules and policies and regulations and stipulations are innovation killers. People do their best work when they’re unencumbered. If you’re spending a lot of time accounting for the time you’re spending, that’s time you’re not innovating.’” Their policy, or lack thereof, has not resulted in the company going out of business, which many of us, if we were stockholders, would fear it would. In fact, just the opposite. Freed from micro-managing bosses, their employees work even harder. Obviously this is not the same thing as the assurance we have in Christ, but perhaps it is not so different either.

April 15, 2013

All Is Grace

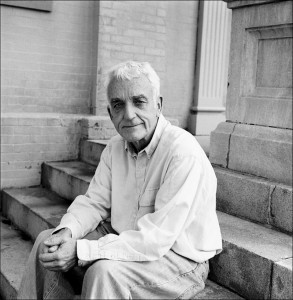

Brennan Manning died Friday night.

Brennan Manning died Friday night.

Long before the recent resurgence of interest in “gospel-centrality”, Brennan was a voice calling out in the wilderness–a voice reminding us that we are great sinners but God is a greater Savior. Theologically quirky and personally idiosyncratic, he was nevertheless a broken man on a passionate mission to remind Christians of the truth that while our sin reaches far, God’s grace reaches farther. He desperately wanted bedraggled, beat-up, and burned-out Christians (like himself) to recover a sense of God’s “furious love” for them.

A lifelong alcoholic who spent his entire life ferociously battling the demon of addiction, he was uncomfortably transparent about his weaknesses and failures which made him a prime candidate to teach us something of God’s scandalous grace (2 Corinthians 12:9). Every addict I’ve ever known–every person who has crashed and burned and, as a result, come to terms with their own powerlessness–has taught me something about God’s grace that I would’ve never known otherwise.

Brennan’s life (tragic and sad as it was, according to him) was a living testimony that horizontal consequences for sin (they led to untold miseries in Brennan’s life) cannot forfeit the “no condemnation” that is ours in Christ Jesus. This was his hope. His lifeline. Unable to bank anything on himself, he banked everything on Jesus. In this sense, his well-documented weaknesses were a gift to him. And to us.

I never had the chance to meet Brennan, but I know many who knew him well…and their lives were never the same. He knew Jesus, loved Jesus, and is now with Jesus…finally enjoying the full measure of the freedom he longed to experience.

The night after he died, I sat in bed and read (once again) these amazing words from his bestselling book The Ragamuffin Gospel–a man after my own heart:

Put bluntly, the American church today accepts grace in theory but denies it in practice. We say we believe that the fundamental structure of reality is grace, not works–but our lives refute our faith. By and large, the gospel of grace is neither proclaimed, understood, nor lived. Too many Christians are living in a house of fear and not in the house of love.

Our culture has made the word grace impossible to understand. We resonate with slogans such as:

“There’s no free lunch.”

“You get what you deserve.”

“You want love? Earn it.”

“You want mercy? Show that you deserve it.

“Do unto others before they do unto you.”

“By all means, give others what they deserve but not one penny more.”

A friend told me she overheard a pastor say to a child, “God loves good little boys.” As I listen to sermons with their pointed emphasis on personal effort–no pain, no gain–I get the impression that a do-it-yourself spirituality is the American fashion.

Though the Scriptures insist on God’s initiative in the work of salvation–that by grace we are saved, that the Tremendous Lover has taken to the chase–our spirituality often starts with self, not God…We sweat through various spiritual exercises as if they were designed to produce a Christian Charles Atlas. Though lip service is paid to the gospel of grace, many Christians live as if only personal discipline and self-denial will mold the perfect me. The emphasis is on what I do rather than on what God is doing. In this curious process God is a benign old spectator in the bleachers who cheers when I show up for morning quiet time. Our eyes are not on God. At heart we are practicing Pelagians. We believe that we can pull ourselves up by our bootstraps–indeed, we can do it ourselves.

Sooner or later we are confronted with the painful truth of our inadequacy and insufficiency. Our security is shattered and our bootstraps are cut. Once the fervor has passed, weakness and infidelity appear. We discover our inability to add even a single inch to our spiritual stature. Life takes on a joyless, empty quality. We begin to resemble the leading character in Eugene O’Neill’s play The Great God Brown: “Why am I afraid to dance, I who love music and rhythm and grace and song and laughter? Why am I afraid to live, I who love life and the beauty of flesh and the living colors of the earth and sky and sea? Why am I afraid to love, I who love love?”

Something is radically wrong.

Our huffing and puffing to impress God, our scrambling for brownie points, our thrashing about trying to fix ourselves while hiding our pettiness and wallowing in guilt are nauseating to God and are a flat out denial of the gospel of grace.

With Brennan, I concur that it is high time for the church to honor its Founder by embracing sola gratia anew, to reignite the beacon of hope for the hopeless and point all of us bedraggled performancists back to the freedom and rest of the Cross. To leave our “if’s” “and’s” or “but’s” behind and get back to proclaiming the only message that matters—and the only message we have—the Word about God’s one-way love for sinners. It is time for us to abandon once and for all our play-it-safe religion, and, as Robert Farrar Capon so memorably put it, to get drunk on grace. Two hundred-proof, unflinching grace. It’s shocking and scary, unnatural and undomesticated…but it is also the only thing that can set us free and light the church, and the world, on fire.

Brennan “got” that. He “gets it” even better now.

See you on the other side, brother!

April 12, 2013

Confessions of a Performancist

Legendary college football coach Urban Meyer tells a remarkable story about his father. During his senior year of high school Urban was drafted by the Atlanta Braves to play major league baseball. Soon after arriving in the minor leagues, however, he realized he didn’t have the necessary talent and called his father to tell him he was quitting. His father informed Urban that if he quit, he would no longer be welcome in their home. “Just call your mom on Christmas,” he said. Needless to say, Urban finished out the season and ended up embracing the incredibly conditional world of his father, a world in which failure was simply not an option, and reflection another word for “weakness wrapped in nostalgia.”

Legendary college football coach Urban Meyer tells a remarkable story about his father. During his senior year of high school Urban was drafted by the Atlanta Braves to play major league baseball. Soon after arriving in the minor leagues, however, he realized he didn’t have the necessary talent and called his father to tell him he was quitting. His father informed Urban that if he quit, he would no longer be welcome in their home. “Just call your mom on Christmas,” he said. Needless to say, Urban finished out the season and ended up embracing the incredibly conditional world of his father, a world in which failure was simply not an option, and reflection another word for “weakness wrapped in nostalgia.”

Urban went on to win back-to-back national championships as the coach for the Florida Gators, and some would chalk his success up to his uncompromising attitude and work ethic. It certainly helped. But it turns out that these victories were short-lived, at least as far as Urban was concerned. The screws only got tighter; once he had won those titles, anything but perfection would be viewed as failure. After the 2007 season, Urban apparently confessed to a friend that anxiety was taking over his life and he wanted to walk away. He was quoted in 2011 as saying, “building takes passion and energy. Maintenance is awful. It’s nothing but fatigue. Once you reach the top, maintaining that beast is awful.” One commentator described him as “a man running for a finish line that doesn’t exist.” Soon the chest pains started, and then they started getting worse. A few hours after the Gators winning streak finally came to an end in 2009, Urban was found on the floor of his house, unable to move or speak. He had come to a breaking point. Soon he would resign, come back and resign again.

Urban Meyer’s story may be a bit extreme, but perhaps you can relate. Perhaps you had a demanding father or mother, for whom nothing was ever good enough. Perhaps they are long gone but you still hear their voice in your head. Perhaps you have a spouse that never seems to let up with the demand, for whom successes are not really successes; they’re simply non-failures. You see, as gifted and driven as Urban Meyer was and is, no one can live under the burden of perfection forever. It may work for a while, but sooner or later, we hit the wall. Even when Urban was fulfilling all righteousness, record-wise, he wasn’t doing it out of love of the game or the joy of shepherding young men, but out of fear of weakness and fear of what it would mean if he lost. If righteousness is a matter of motivation as well as action, then even when he was meeting the standards of performance set by his father, he wasn’t really meeting them.

Urban had fallen victim to a vicious form of performancism. He had become a slave to his record, where the points scored on the field were more than just a proud part of his team’s tally but a measure of his personal worth and identity.

I got my first tennis racket on my seventh birthday. And because we had a tennis court in our backyard, I played every day. By ten I was playing competitively. Everyone around me marveled at my natural ability. I would constantly hear how great I was for being so young, how much potential I had to “really go somewhere.” All of this made me feel important. It made me feel like I mattered. Without realizing it I began to anchor my sense of worth and value in being a great tennis player.

I had a problem, though. Whenever I would hit a bad shot or lose a point, I would throw a John McEnroe-like temper tantrum. I would yell, curse, break my racket, etc. Numerous times my parents and coaches would counsel me, telling me I had to get myself under control. But I couldn’t. No matter how hard I tried, I just couldn’t. I didn’t know why back then but I do now. Every lost point, game, set, and match threatened my identity. I unconsciously concluded that if I didn’t become the best, I’d be a nobody; If I didn’t win, I didn’t count. If I wasn’t successful, I would be worthless.

I was experiencing what Paul Zahl calls, “the law of capability”—the law that judges us wanting if we’re not capable, if we can’t handle it all, if we don’t meet the expectations that we put on ourselves or that others put on us. Zahl describes it this way:

If I can do enough of the right things, I will have established my value. Identity is the sum of my achievements. Hence, if I can satisfy the boss, meet the needs of my spouse and children, and still pursue my dreams, then I will be somebody. In Christian theology, such a position is called justification by works. It assumes that my worth is measured by my performance. Conversely, it conceals a dark and ghastly fear: If I do not perform, I will be judged unworthy. To myself I will cease to exist.

After Urban Meyer’s very public collapse, he took some time off. He went on a road trip with his son. He attended his daughter’s volleyball games. He made peace with his father. He even rediscovered the reason he got into football in the first place: love of the game. Eventually he took a new position as coach for Ohio State, and above his new desk he hung his contract—not the contract he signed with the university, but the one he signed with his wife and children, the one which prioritized his family and his health. An expression of love rather than judgment. It’s a beautiful story, and it’s not over.

An article about Urban during his transition mentions a book that he used to live by, written for business executives, called Change or Die. He has talked about the book in speeches, given away countless copies, invited the author to meet with his teams, but never did he realize the book described him, down to a tee. The article recounts an episode that occurs in the car on the way to Cleveland, in which someone reads Urban a passage from the book:

“Why do people persist in their self-destructive behavior, ignoring the blatant fact that what they’ve been doing for many years hasn’t solved their problems? They think that they need to do it even more fervently or frequently, as if they were doing the right thing but simply had to try even harder.”

Meyer’s voice changes, grows firmer, louder. “Blatant fact,” he says. He pauses. A fragmented idea orders itself in his mind. “Wow,” he says. He asks to hear it again. “Blatant fact,” he says. “It should have my picture. I need to read that to my wife. I’m gonna reread that now. Self-destructive behavior?”

This is a man who was addicted to the law, so much so that it destroyed him. Yet his defeat turned out not to be the end he feared it would be, but the beginning of something new, the advent of a man finally free enough from the stranglehold of narcissistic performancism that he could not only laugh at himself but begin to love those around him. Self-destruction was not the end of his story, neither is the Law the end of ours.

The law is God’s first word, but thank God it’s not the last. The last word is the one that comes straight from the mouth of Jesus himself, when he says, “For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.”

If you’re a Christian, here’s the good news: Who you really are has nothing to do with you—how much you can accomplish, who you can become, your behavior (good or bad), your strengths, your weaknesses, your sordid past, your family background, your education, your looks, and so on. Your identity is firmly anchored in Christ’s accomplishment, not yours; his strength, not yours; his performance, not yours; his victory, not yours.

April 6, 2013

Set Free By The Judgement Of God

Robert Kolb and Charles Arand wrote an incredibly engaging book called The Genius of Luther’s Theology: A Wittenburg Way of Thinking for the Contemporary Church. I highly, highly recommend it.

Robert Kolb and Charles Arand wrote an incredibly engaging book called The Genius of Luther’s Theology: A Wittenburg Way of Thinking for the Contemporary Church. I highly, highly recommend it.

Of the book, Michael Horton writes, “Aside from a few slogans and provocative quotes, Luther’s theology is largely unknown in the land that Bonhoeffer called ‘Protestantism without the Reformation.’ Christianity in America desperately needs the wisdom and penetrating insight into gospel logic that is winsomely introduced in this rewarding volume.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Buy it. Today.

I was especially gripped by these sentences written in the context of discussing Luther’s categories of passive and active righteousness (I’m absolutely convinced that if the church understood these two crucially important categories, most of our confusion with regard to law and gospel, faith and works, would go away. For more on passive and active righteousness read this).

Kolb and Arand write:

Living on the basis of Christ’s righteousness involves the recognition that God’s judgement contradicts the judgement that others make about us, as well as the judgement we render on ourselves. Daily life–the home, workplace, community, society–provides the context for an unending series of performance evaluations in which our capabilities and competencies are under constant critique. In these settings and relationships, we are forced to consider how others see us and judge us.

We also have to live with the image that we have of ourselves as we enter the world around us with respect to education, promotions, finances, popularity, and social mobility. Such daily audits of our own self-evaluation and the daily audit of how others evaluate us will continue until death. Nevertheless, the balance sheet does not have the first and last say about my existence.

The passive righteousness of faith ultimately frees us from being determined now and finally by such an audit. It frees me from pronouncing final judgement on myself. The passive righteousness of faith also frees me from what others say about me, for what they say is not the final judgement, but is always provisional.

For faith believes God’s gracious judgement despite all empirical evidence to the contrary. In other words, we cling to the promise regardless of how many times instant replays of our weaknesses and failures flash before my eyes.

Indeed, the gospel not only frees us from what others think about us–it frees us from what we think about ourselves.

Amen!

April 2, 2013

Grace Prevails

When talking about “the law”, we need to make an important distinction. We can call it big “L” Law and little “l” law. Big “L” law comes from God and is outlined in the Ten Commandments, reiterated in the Sermon on the Mount, and summarized by Jesus as the command to “Love the Lord with all of our heart, mind, soul, and strength…and love our neighbor” (of course, one could say more but that’s the gist of it). But there’s another law (little “l”) that plays out in all kinds of ways in daily life. Paul Zahl puts it this way:

When talking about “the law”, we need to make an important distinction. We can call it big “L” Law and little “l” law. Big “L” law comes from God and is outlined in the Ten Commandments, reiterated in the Sermon on the Mount, and summarized by Jesus as the command to “Love the Lord with all of our heart, mind, soul, and strength…and love our neighbor” (of course, one could say more but that’s the gist of it). But there’s another law (little “l”) that plays out in all kinds of ways in daily life. Paul Zahl puts it this way:

Law with a small “l” refers to an interior principle of demand or ought that seems universal in human nature. In this sense, law is any voice that makes us feel we must do something or be something to merit the approval of another. For example, what we shall call “the law of capability” is the demand a person may feel that he/she be 100% capable in everything he/she does-or else! In the Bible, the Law comes from God. In daily living, law is an internalized principle of self-accusation. We might say that the innumerable laws we carry inside us are bastard children of the Law.

No one understood the dynamic of how the accusation of the law functions in the human psyche better than Martin Luther. He characterized the Law as, “a voice that man can never stop in this life,” one that can be heard anywhere and everywhere, not just on Sunday morning. It takes any number of forms, but its function remains the same: it accuses. Indeed, the “oughts” of life are as numerous as they are oppressive: infomercials promising a better life if you work at getting a better body, a neighbor’s new car, a beautiful person, the success of your co-worker- all these things have the potential to communicate “you’re not enough.”

The other day I was driving down the road near my house and I passed a sign in front of a store that read, “Life is the art of drawing without an eraser.” Meant to inspire drivers-by to work hard, live well, and avoid mistakes, it served as a booming voice of law to everyone that read it: “Don’t mess up. There are no second chances. You better get it right the first time.” Again, Paul Zahl chimes in insightfully:

In practice, the requirement of perfect submission to the commandments of God is exactly the same as the requirement of perfect submission to the innumerable drives for perfection that drive everyday people’s crippled and crippling lives. The commandment of God that we honor our father and mother is no different in impact, for example, than the commandment of fashion that a woman be beautiful or the commandment of culture that a man be boldly decisive and at the same time utterly tender.

The world is full to the brim with law. Not just laws of Scripture, laws of science, and tax codes, but lesser, subjective laws. And they cause us enormous grief. Indeed, identity is an area of life frequently mired in legalities: “I must be __________ kind of person, and not ___________ kind of person if I’m ever going to be somebody.”

An environment of law, as we all know, is an environment of fear. We are afraid of the judgment that the law wields. Or as the poet Czeslaw Milosz describes in his poem “A Many-Tiered Man”: “[Man] frightened of a verdict, now, for instance, or after his death.” We instinctively know that if we don’t measure up, the judge will punish us. When we feel this weight of judgment against us, we all tend to slip into the slavery of self-salvation: trying to appease the judge (friends, parents, spouse, ourselves) with hard work, good behavior, getting better, achievement, losing weight, and so on. We conclude, “If I can just stay out of trouble and get good grades, maybe my mom and dad will finally approve of me; If I can overcome this addiction, then I’ll be able to accept myself; If I can get thin, maybe my husband will finally think I’m beautiful; if I can make a name for myself and be successful, maybe I’ll get the respect I long for.”

The law stifles and causes us to second-guess ourselves. Have you ever found yourself writing and rewriting the same email over and over again? Or procrastinating on making a phone call? The recipient almost inevitably has become a stand-in for the law. We put people in this role with alarming facility.

The idea of “law” simply makes sense, and universally so. The Apostle Paul even claims that it is written on the heart (Romans 2:15). In fact, those that don’t believe in God tend to struggle with self-recrimination and self-hatred just as much as those that do; no one is free of guilt—the law is not subject to our belief in it. Some of us even compound our failures and suffering by heaping judgment upon judgment, intoxicated by the voice of “not-enoughness”, not content until we have usurped the role of the only One who is actually qualified to pass a sentence. In a 2005 interview with journalist Michka Assayas, U2 frontman Bono spoke eloquently about Law and Grace in terms of Karma:

At the center of all religions is the idea of Karma. What you put out comes back to you: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, or in physics, every action is met by an equal and opposite one. It’s clear to me that Karma is at the very heart of the Universe. I’m absolutely sure of it. And yet, along comes this idea called Grace to upend all that “as you reap, so will you sow” stuff. Grace defies reason and logic. Love interrupts the consequences of your actions, which in my case is very good news indeed, because I’ve done a lot of stupid stuff… I’d be in big trouble if Karma was going to finally be my judge. It doesn’t excuse my mistakes, but I’m holding out for Grace. I’m holding out that Jesus took my sins onto the Cross, because I know who I am, and I hope I don’t have to depend on my own religiosity.

Against the tumult of conditionality-punishment and reward, score-keeping, Karma, you-get-what-you-deserve, big “L” Law, little “l” law, whatever name you choose—comes the second of God’s two words, His Grace. Grace is the gift that has no strings attached. It is one-way love. It is what makes the Good News so good, the once for all proclamation the there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:1). It is the simple equation that Jesus plus Nothing equals Everything.

Against the tumult of conditionality-punishment and reward, score-keeping, Karma, you-get-what-you-deserve, big “L” Law, little “l” law, whatever name you choose—comes the second of God’s two words, His Grace. Grace is the gift that has no strings attached. It is one-way love. It is what makes the Good News so good, the once for all proclamation the there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:1). It is the simple equation that Jesus plus Nothing equals Everything.

The Gospel of Grace announces that Jesus came to acquit the guilty-he came to judge and be judged in our place. Christ came to satisfy the deep judgment against us once and for all so that we could be free from the judgment of God, others, and ourselves. He came to give rest to our efforts at trying to deal with judgment on our own. The Gospel declares that our guilt has been atoned for, the law has been fulfilled. So we don’t need to live under the burden of trying to appease the judgment we feel; in Christ the ultimate demand has been met, the deepest judgment has been satisfied. The internal voice that says “Do this and live” only get’s outvolumed by the external voice that says “It is finished!”

Yet there is nothing that is harder for us to wrap our minds around than the unconditional, non-contingent grace of God. In fact, it “defies our reason and logic,” upending our sense of fairness and offending our deepest intuitions, especially when it comes to those who have done us harm. Like Job’s friends, we insist that reality operate according to the predictable economy of reward and punishment. Like the elder brother in the Parable of the Prodigal son, we have worked too hard to give up now. The storm may be raging all around us, our foundations may be shaking, but we would rather perish than give up our “rights.”

Yet still the grace of God prevails! His gracious disposition toward us thankfully does not depend even on our ability to comprehend it. When we finally come to the end of ourselves, there it will be. There He will be. Just as He will be the next time we come to the end of ourselves, and the time after that, and the time after that.

March 27, 2013

Pictures Of Grace

As my dear friends Bert and Christine DeVries testify below, God’s grace becomes functionally real in the context of catastrophe.

Devries Testimony from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

“God’s office is at the end of our rope.” John Zahl

March 22, 2013

The Fruit of Grace

Hollywood is not known as a culture of grace. Dog eat dog is more like it. People love you one day and hate you the next. Personal value is very much attached to box office revenues and the unpredictable and often cruel winds of fashion. It was doubly shocking, therefore, when one way love—and its fruit—made such a powerful appearance on the big stage in 2011. The occasion for it was Robert Downey Jr receiving the American Cinematheque Award, a prize given to “an extraordinary artist in the entertainment industry who is fully engaged in his or her work and is committed to making a significant contribution to the art of the motion pictures.” A big deal, in other words. Downey Jr. was allowed to choose who would present him with the award, and he made a bold decision. He selected his one-time co-star Mel Gibson to do the honors.

Hollywood is not known as a culture of grace. Dog eat dog is more like it. People love you one day and hate you the next. Personal value is very much attached to box office revenues and the unpredictable and often cruel winds of fashion. It was doubly shocking, therefore, when one way love—and its fruit—made such a powerful appearance on the big stage in 2011. The occasion for it was Robert Downey Jr receiving the American Cinematheque Award, a prize given to “an extraordinary artist in the entertainment industry who is fully engaged in his or her work and is committed to making a significant contribution to the art of the motion pictures.” A big deal, in other words. Downey Jr. was allowed to choose who would present him with the award, and he made a bold decision. He selected his one-time co-star Mel Gibson to do the honors.

To say that Mel’s reputation had taken a serious nosedive in recent years would be a severe understatement. An arrest for drunk driving in 2006 in which the actor-director spewed racist and anti-Semitic epithets was followed by public infidelity and a high profile divorce in 2009 and then culminated in 2010 when tapes of a drunken Gibson berating his then-girlfriend in the most foul manner imaginable were released online. Reprehensible does not even begin to describe it. Downey Jr’s ceremony took place a little more than a year after that final incident, the one that rightly cemented Gibson’s place as pariah numero uno in Tinseltown.

Of course, Downey Jr was no stranger to ostracization. In the 1990s, he became something of punchline himself as someone notoriously unable to kick a violent addiction to drugs and alcohol. Arrest after arrest, relapse after relapse, people both in Hollywood and elsewhere began to think of him less as an actor and more as a junkie. Professionally he became a liability—even those who wanted to work with him couldn’t because insurance companies wouldn’t underwrite a film if he was part of the cast. Bit by bit, and with the notable help of some good friends, Downey Jr eventually got sober and his career slowly got back on track. In 2008 he was cast as Iron Man and the rest, as they say, is history. Today he is one of the most beloved and highest grossing actors in the business. So the award coincided with the very height of his popularity and the nadir of Gibson’s. This was his moment of glory.

Instead of using his acceptance speech to give an “aw shucks” to the crowd of adoring colleagues, and doff his hat to his agent and family, Downey Jr did something unprecedented. We’ll let him speak for himself:

I asked Mel to present this award to me for a reason. Because when I couldn’t get sober, he told me not to give up hope, and he urged me to find my faith—didn’t have to be his or someone else’s—as long as it was rooted in forgiveness. And I couldn’t get hired so he cast me in the lead in a movie that was actually developed for him. He kept a roof over my head, and he kept food on the table. And most importantly, he said that if I accepted responsibility for my wrongdoings and embraced that part of my soul that was ugly—”hugging the cactus” he calls it—he said that if I “hugged the cactus” long enough, I would become a man of some humility and my life would take on new meaning. And I did and it worked. All he asked in return was that some day I help the next guy in some small way. It’s reasonable to assume that at the time he didn’t imagine the next guy would be him. Or that some day was tonight.

Anyway, on this special occasion… I humbly ask that you join me—unless you are completely without sin (in which you picked the wrong… industry)—in forgiving my friend his trespasses, offering him the same clean slate you have me, and allowing him to continue his great and ongoing contribution to our collective art without shame. He’s hugged the cactus long enough. [And then they hug].

The short speech not only testifies to the amazing power of one-way love, it is itself a beautiful example of the ‘fruit” of one-way love. At his lowest point, Downey Jr. was shown mercy by Mel Gibson. He didn’t deserve it, his track record was abysmal, but Mel, for whatever reason, took a risk—at great cost to himself. He personally paid down the massive insurance premium for Downey Jr. on 2003′s The Singing Detective so that his friend could get back on his feet. You don’t forget something like that.

Downey Jr’s response was one of gratitude and generosity. His speech may have phrased things in terms of repayment, but Mel’s injunction was obviously an after-the-fact suggestion rather than a condition. Downey Jr’s gesture goes so far beyond any sense of “owing”, especially considering the choice of moment and venue. To associate with Mel in such a public manner, indeed to advocate for him, meant putting Downey Jr’s own reputation on the line. It was a self-sacrificial and even reckless move. There was no possible gain for Downey Jr.; such was the antipathy that Mel inspired. No, his defense of the indefensible was the uncoerced act of a heart that’s been touched by one-way love. There is a direct line from the love Downey Jr was shown to the love he then shows. His supreme generosity is the fruit of grace.

Downey Jr’s response was one of gratitude and generosity. His speech may have phrased things in terms of repayment, but Mel’s injunction was obviously an after-the-fact suggestion rather than a condition. Downey Jr’s gesture goes so far beyond any sense of “owing”, especially considering the choice of moment and venue. To associate with Mel in such a public manner, indeed to advocate for him, meant putting Downey Jr’s own reputation on the line. It was a self-sacrificial and even reckless move. There was no possible gain for Downey Jr.; such was the antipathy that Mel inspired. No, his defense of the indefensible was the uncoerced act of a heart that’s been touched by one-way love. There is a direct line from the love Downey Jr was shown to the love he then shows. His supreme generosity is the fruit of grace.

Mel clearly had no idea about what Downey Jr. was planning to do. And Downey Jr’s tone and demeanor make it very clear that he was not putting himself out there under duress—he did it because he wanted to. His ability and desire to show mercy seems almost directly proportional to his personal experience of it, his firsthand knowledge that he is just as much in need of mercy as “the chief of sinners”. His plea, in other words, was rooted in humility about his own sin and gratitude for the love he has been shown, which asserts itself in kind. Belovedness births love. Grace accomplished what no amount of court-ordered, legal remedies ever could: it created a heart that desires to show mercy to the “least of these.”

Of course, as powerful of a story as it is, the episode is not a one-to-one analogy for the Gospel—no story could be. As impressive as Iron Man is, he is not God. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t close. Thankfully, when it comes to God’s grace, there is not even a hint of exchange. No suggestion of payback, or pay it forward. There are no strings attached. Only grace can change a heart and produce law-fulfilling works of mercy, but grace is not dependent on a changed heart or law-fulfilling works of mercy. Grace alone produces the conditions that induce change, but grace is not conditional on change. It is pure gift. Our greatest hope. Our only comfort. Our deepest relief.

It is one way love.

(Excerpted from my forthcoming book One Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World)

March 20, 2013

What Does A Free Life Look Like?

Boldness, security, generosity, love, peace, confidence, courage, compassion. This is what life begins to look like when your heart is grasped by the fact everything you need, in Christ you already possess:

Boldness, security, generosity, love, peace, confidence, courage, compassion. This is what life begins to look like when your heart is grasped by the fact everything you need, in Christ you already possess:

Let love be genuine. Abhor what is evil; hold fast to what is good. Love one another with brotherly affection. Outdo one another in showing honor. Do not be slothful in zeal, be fervent in spirit, serve the Lord. Rejoice in hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer. Contribute to the needs of the saints and seek to show hospitality.

Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them. Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep. Live in harmony with one another. Do not be haughty, but associate with the lowly. Never be wise in your own sight. Repay no one evil for evil, but give thought to do what is honorable in the sight of all. If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all. Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” To the contrary, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

The Apostle Paul (Romans 12:9-21)

March 15, 2013

Grace And Media

At LIBERATE 2013, my good friend David Zahl (Founder and Director of Mockingbird Ministries) delivered an incredibly insightful talk on grace and media. This truly is a must see:

Liberate 2013 – David Zahl from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers