Frater Acher's Blog, page 3

December 25, 2020

How to Read a Book.

Even the most simple things can benefit from a healthy dose of critical thinking. Reading non-fiction books often is counted among such simple things. How hard can it be? We open the cover of a book and begin to encounter the author’s voice. They present us with facts and stories, page upon page, and while we continue to read, slowly, we begin to push out the walls of our own storehouse of knowledge. Through the act of reading, we begin to expand the boundaries of our minds.

Unfortunately, as we all know, that is a highly idealized idea of what happens when we read. The reality is much more messy and chaotic: Our consciousness drifts in and out, we stop, check our phones, and pick up the book again days later; most importantly though, the ties around our mind of what we already know (or believe to know) are incredibly tight and not at all easily loosened. And as we encounter the author’s voice in the isolation of our intellect, we often don’t hesitate to judge quickly. Reading in such partisan style ceases to be an exploration into new and unknown territories; instead, it degrades into the repetitious act of ‘mind-sorting’ new information against mental compartments we created long ago, quickly dismissing anything that doesn’t easily fit or gel well with boxes we established and labeled once when our mind was still open.

Holding a firm opinion is not at all the sign of an educated mind. In fact, mostly it is the reverse: Only once we have delved deep enough into a subject we begin to see its paradoxes, entanglements, and inconsistencies. But there is no way to ‘delve deep’ into any subject unless we proactively loosen our mind’s ties to what we think we know already.

When we sit down and open a book, magical books especially, we should be prepared to be assaulted in the present moment, and possibly come out of it forever changed. Such change, however, will rarely ever happen if we keep up the drawbridge of our convictions and send the archers to the battlements of our established worldview. Reading a book, reading any magical book indeed, is the art of inviting in the poison that might dissolve the foundations of our faith. As adepts of the magical art this should not at all pose as a thread, but ultimately an aspiration. For faith — here not in its Paracelsian sense, but in its ordinary definition as ideas we’d like to be real, but have little evidence for — is the game we go on the hunt for when opening the covers of a book.

Truly engaging with a book, truly reading it, turns out to require much more courage than it initially seems. The courage to overcome, in this case though, is no longer directed at the outside world, but against ourselves. Just like we should only engage in practical magic if we are open to being changed in the process, the same logic applies to reading a book. If we are on the lookout for cognitive flattery and intellectual affirmation let’s scroll through our social media feeds. In stark contrast, a good book is a tool for revolution against oneself. Reading in this essential sense of the word means being prepared to putting the torch to our established ways of ‘sense-making’. Turning another page becomes the act of swimming upstream against the current of our established mind. It is in this manner that all good books we’ll ever encounter are deeply heretical to the things we thought we knew.

More than 230 years ago the German lawyer, philosopher and Rosicrucian mystic Karl von Eckartshausen (1752-1803), author of The Cloud upon the Sanctuary, provided us with wonderful inspiration on how to read a book. By following his instructions we begin to see how much effort it can take to absorb a single sentence, let alone a chapter. Whether we have read a book in this sense is no longer a function of how quickly we made it from front to back cover, but how deeply we have engaged with what lies in-between.

Thus if I assess the writings of the proponents of Enlightenment in our own time, I initially search for whether there is truth in the book that I am reading; for where there is no truth, there is no enlightenment, and where there is passion, there is rarely ever truth. I do not immediately imagine the author as a philosopher, but first I want to see if they deserve the title which they claim. So I place the author back amongst the natural man [Naturmenschen], I hand them back their passions, and I observe how much their self-love and self-interest have influenced their writing. From there onwards I carefully watch how much their education, their temperament reveals themselves in their writing; for writing is physiognomy of the soul, and a sharp eye can distinguish indeed true emotion from artificial expression.

There is a language of the intellect, a language of the wit and a language of the heart. In the language of the intellect the heart often times holds no part; but to the language of the heart the intellect often times is united. The language of wit many a time is the interpreter of the evil heart.

Once I have looked at the author from all these angles, I subtract from their work what is education and temperament, and what was affected by the situation of their writing and the general circumstances of their time. Whatever remains I weigh with the plumb level of truth: What stands this test is good, what does not is evil.

— Karl von Eckartshausen, Über Religion, Freydenkerey und Aufklärung, München: Johann Baptist Strobl, 1786, p. 20/21, translation by Frater Acher

Whenever we put a book down, the essential question is not whether we recall what is printed on its pages, but the horizon of exploration expands far beyond that: What is it that we just learned about the time of the book’s emergence, about the culture and intellectual milieu it was born from, about the circumstances its author was in when writing it; and, maybe most importantly, what have we learned about the author’s voice itself? Have we already killed its unique timbre and assimilated it into the museum of our dead knowledge? Or will we be able to channel it when we engage on the same topic in the future? Have we learned to speak to the author in our own mind, beyond the pages of this book? From here onwards, can we distinguish their voice in the intellectual spirit choir that is the hive of our open mind? — If we answer with yes, we genuinely have read a book, and probably expanded our mind irreversibly.

Now, should you be reading these lines as an author yourself, allow me one last quote from Eckartshausen’s wonderful work.

He not only advises us on how to get the best of any nonfiction books as recipients of their contents, he also offers perspective on how to approach our readers as authors. While his words were directed at himself as well as his peers writing during the time of Enlightenment, they remain real and true long beyond the time from which they stemmed.

Here is to more of us opening their notebooks, picking up their pens in the spirit of this great Rosicrucian mystic:

The true proponent of Enlightenment is mostly kind, he has gentleness against everyone; he attacks vices and protects the human. He observes his own heart, is always alert towards his own mind, does not force his opinion on anyone, has no addiction to proselytism, but allows truth to hold its own victories. He is not proud of his opinion and neither passionate in his critique. His purpose is to lead people to their happiness, and his proof is in his own experience […].

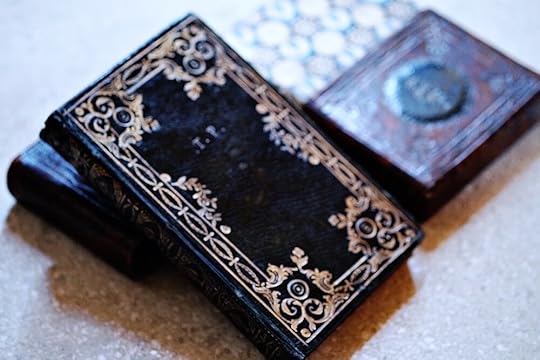

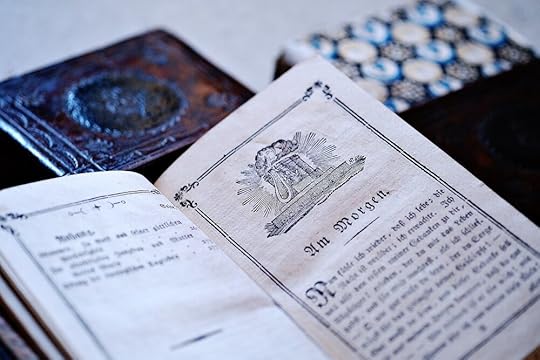

— Karl von Eckartshausen, Über Religion, Freydenkerey und Aufklärung, München: Johann Baptist Strobl, 1786, p. 18, (image of custom bound 1st edition below)

December 23, 2020

The Four Saboteurs and the Devil that is Guilt.

Well, it’s no longer a surprise that 2020 has been a whip of a teacher. Before we close this year full of adversity, let me share two specific lessons I took from its lashes. Actually, the truth is, I had come across these lessons long before. But boy, had I become lax in observing them as every day realities? Realities that don’t hesitate to kick us in the gut, unless we respect their simple dynamics in both mundane as well as magical applications. With this in mind, let’s put a spell on 2021.

Here is to a most resilient year ahead for you all. And may you treat yourself like you’d treat your best friend.

LVX,

Frater Acher

We all breed dreams of grandiosity. Who we’d like to be to the world. How we’d like to be seen, recognized, admired. Whatever these dreams are, at the end of the day their effect on our identities mostly boil down to four simple rules: We all want to look good and be liked; we all want to be right and in control. Being admired and being liked, being right, and being in control. Such a simple recipe to describe the dullest and yet most appealing of all places: the inner circle of our comfort zone. A hypothetical space free of any kind of self-doubt and hostility, but brimming with social admiration and tribal anchorage.

Experiencing these four saboteurs is essentially human. We all encounter them all the time. And yet they are amongst the most powerful agents to undermine any kind of lasting happiness. This is especially true in times of crisis, as the four saboteurs encourage us to lead a highly egocentric and self-involved lifestyle. Rather than engaging with what is going on around us, they manipulate us to use the world as a mirror as a fake version of ourselves. In following their urge, the world deteriorates from an open map of adventures, into an exploitative tool for making our small selves look good, be liked, be in control and appear smart. Still, trying to comply with the demands of the four saboteurs presents an enormous amount of work, very hard work indeed, and one that wants to be accomplished ideally in every single interaction we encounter. More often than not, we will fail to succeed in satisfying at least one of the four and thus be left disappointed about ourselves or the world around us. The potential for anger, despair, guilt, and self-doubt is endless. This is why these four saboteurs are omnipresent in most of our interactions, while actual happiness remains mostly absent.

Now, the very nature of a crisis is to cut off our ability to successfully cater for these four drivers. Crisis, whether experienced collectively or individually, diminishes our control, it proves our previously held assumptions wrong and throws us into a whirlwind that knocks any graceful performance into crawling and shuffling. From a mystical viewpoint, crises are awesome opportunities. They present the perfect time to shed all skins of ‘I, Me and Mine’, as the radical mystic Johannes Tauler († 1361) called it.

Several centuries later, but speaking from the same spirit, Martin Buber coined the wonderful phrase: ‘Don’t look at yourself, but look at the world.’ What a stark reminder 2020 has been of the power of such an attitude towards ourselves and the world. Maybe in 2021, we should experiment with such an approach towards life more boldly: Let us all look foolish and flawed, let us all be proven wrong and surrounded by chaos – as long as we have each other’s back. Let’s stop competing for momentary adoration and superficial perfection. Let’s smile upon our flaws and failures instead. And begin to treat each other with the gentleness that we so crave to be treated with ourselves.

The Devil that is Guilt.This is a conversation I have had with countless people in 2020. Trying to escape from the stronghold of the four saboteurs means we need to take care of our own needs first. Growing up to take care of ourselves describes a lifestyle where we no longer wait for others to satisfy our essential human needs, but become masters in doing this ourselves. Only then can we stand free from the expectation to receive something back from the world, and truly encounter its wonder and magic, unveiled from the filters of our own cravings.

Unfortunately though, most of us are overcome by strong sensations of guilt when we attend to our own needs. Ironically, when we actually do the job only we can do (i.e. taking care of ourselves), this inner demon voice tells us we are already treading on the edge of sin and damnation. We can choose to blame our Calvinistic ancestors, Catholic Christianity all up, or, closer to home, our own parents, bosses, or kids. None of that matters though. Because whoever we choose to blame for creating this introjected voice, the only person who can do something about it right now is us. I guess that is what it means to be a grown-up: To be able to differentiate the voice of our consciousness from the voices of inner saboteurs, and then to take the grown-up decision about what we will be doing next. Free will indeed is a burdensome gift.

So here is a suggestion: Next time you do something that is truly good for you alone, freely acknowledge the voices of guilt that might come up, but do not identify with them. Allow these voices to co-exist with you, like bad weather or a torn ankle. These things happen, but they do not need to define us. They can drift into the periphery of our experience, while we hold our space in its center and affirm our intention through action. True courage, they say, is not the absence of fear, but doing what is right despite one’s fear. Similarly looking after ourselves with gentleness and joy does not mean the absence of occasional feelings of guilt; it means doing what is right for us, doing what will make us ready to encounter the world unconditionally, despite our inner co-existence with guilt.

See, at the end of the day this is not going to be pretty one way or the other. As Fritz Perls said, the only way out is through: We can choose to lead our lives unfulfilled, treating the world like a substitute for our own lack of competence in looking after ourselves; or we can do what is right for us, and accept that not everyone will like it. What it is going to be for you? The blue or the red pill in 2021?

After all, the biggest obstacle to becoming the kind of grown-up, who isn’t a constant burden on others, is to responsibly satisfy our own needs whenever it is time to do so. In approaching every day in such a manner, we can become quite okay with the simple but harsh truth that life really owes us nothing.

If I had to distill this down to its essence, it would probably look like this: Four affirmations that have come out of 2020 for me; four spells I am putting on the year ahead; four antidotes against the voices of my inner saboteurs.

Guilt is the enemy.

Fear is the trigger.

Gentleness is a tonic.

Adversity is an invitation.

— A Spell on 2021

October 31, 2020

Clavis Goêtica – An Introduction

Here is a humble gift in a year in which we all deserve some good news: In honouring All Hallows 2020, the one night when even the Christian tradition remembers its goêtic roots and communes with the dead, Erzebet and I are sharing the Introduction of my upcoming book Clavis Goêtica (Hadean Preass, 2021).

While the Holy Daimon Cycle explores the narrow trail of becoming alike to the angelic mind, in this forthcoming book we will throw ourselves into the deep shaft that lands us amongst the dead, the chthonic spirits, and the wisdom of the underworld. As we will see, despite their outer contrast, these journeys might have much more in common than traditional magical narratives make us believe…

Here is to the spark we light for the dead,

and the spirits that speak from their bones.

LVX,

Frater Acher

γοητεία is an Ancient Greek word which literally translates as goêteia (sorcery). The Latinised version goetia reads more familiar to most modern practitioners. In this book I am using the phonetic transcription of the original Greek word to reference the spirit of this work – to return to the origins of this form of chthonic spirit work, stripping away more recent additions or re-interpretations of it.

It was more than ten years ago, in 2010 that Jake Stratton-Kent, with the critical publication of his Geosophia: The Argo of Magic threw the first stone at the glasshouse of Modern Western Magic as we knew it. This stone was thrown from the stained hands of a maverick practitioner who had navigated deep into the terra incognita of ancient magical history. What he had rediscovered, right before the dawn of Greek philosophy in the 6th century BCE, were the ancient shamanic roots of Western Magic: A heritage so unruly and untamed in spirit, it had required immediate binding and exorcising by philosophers and politicians at the time. For a society that was obsessed with the socio-political experiment of the polis could not tolerate a rogue group of charismatic lone-path practitioners undermining the cohesive power of the newly emerging social collective. Thus the ancient term of the goês, the grave-dweller and skull-speaker, quickly became replaced with the fashionable Persian loanword of the mage. Just like Christian churches many centuries later were erected upon heathen sanctuaries, so also much of Western Magic as we know it was erected over the fervid coals and carved skulls of ancient goêtia. – Thus ten years ago, by the stone and glass shards landing in our laps, we were starkly reminded that orthodoxy always is a thin veneer of lies over a much more wild and tangled, truly unorthodox past.

The present volume therefore owes a lot to the work of JSK, as well as authors of earlier publications on the same topic, such as Will-Erich Peuckert, Walter Burkert, Sarah Iles Johnston or Daniel Ogden. What was born from their inspiration, the slender book you hold in your hands or read on your electronic screens, truly is a bastard in the original sense of the word. Being a packsaddle son conceived while traveling on my own journey into the goêtic realm, this book aims to unite critical academic source-knowledge on the origin of the goêtic craft with first-hand experiences, both form yours truly, as well as of practitioners from centuries much closer to our own. Obviously, from an academic vantage point, the pure attempt to unite theory and practice, etic and emic perspectives on chthonic sorcery in the body of a single book discredits any such undertaking from the get go. Especially as we are not even sticking to the fragile guardrails of the method of participative ethnography; rather we have gone native in a pretty absolute sense: Over more than a decade now I have been actively working as a goês in a mountain cave in the Northern-Alps. The real-life as well as spiritual experiences made as part of these journeys, to me at least, hold the same ontological reality or fragility as the very coffee cup I hold in my hands right now. The chthonic spirits with whom I had the chance to commune and collaborate could not be less interested in human psychology, academic publishing standards, or magical lineage for that matter. If anything at all, they hold an active interest in restoring and maintaining the tides of nature – and putting us humans to good work in the spheres of reality that they cannot reach themselves as easily as we do. Neither natural exploitation nor transmutation is their interest, yet if we were to regain their trust, interspecies symbiosis might be.

The structure of this book is similar to the one of Holy Daimon (Scarlet Imprint, 2018): We begin with a foundation in history, then move on to accounts of modern practitioners and conclude with detailed tactical instructions, focussing on the tradition of divining-skulls or teraphim.

Thus we start out by looking into the mirror of our ancient past. Understanding the Ancient Greek mythological sources, that are woven into the very words and practices of this craft, is a necessity before we can attempt to stride out on our own path. The first chapter explores the historic origins of primal goêteia, and was first published in 2017 as Goêteia - explorations in chthonic sorcery on theomagica.com. Particular emphasis is placed upon the role of the Idaian Dactyls, the role of the Great Mother and thus the sensitive function of the goês as an intermediary agent between the Promethean offspring and the primal mother-consciousness most easily accessed through cavernous mountain-wombs.

Following these historic foundations, we touch upon my own goêtic practices over the last decade and critical learnings derived from it, only to correlate the latter to the practice of two goês from High Medieval and Early Modern times. The title of this book, Clavis Goêtica might shine in a different light, once we heard the story of the Rosicrucian adept and white-goês Johannes Beer, and his particular way of using goêtic keys to commune with the spirits of the underworld.

In the final third of this humble volume we are going to work with a Necromantic divination rite whose current manuscript stems from the 18th century, yet whose original roots reach far back into our magical past. This goêtic grimoire not only presents us with an authentic ritual of kephalomancy, i.e. divining from a human skull, but provides an exemplary account of illustrating the shamanic nature of the work of the goês. As we will see, unrestrained by the flawed social morality of their (and still our) time, the practitioner of the Ars Phytonica is invited to establish a juncture between heaven and earth, between chthonic and celestial realms, by means of their direct communion with a host of spiritual beings as well as a simple mantic skull.

We conclude our explorations with a final gift by José Gabriel Alegría, who went beyond the outstanding iconographic contributions to this volume by also including his own written reflections on the Ars Phytonica, in his most succinct essay Of Talking Heads and Solar Skulls.

The purpose of this book, thus, is quintessentially shamanic: These pages are meant to catch fire in your own hands, to burn and turn to ashes, to wash down into the underworld, and to come back to you as a wind - in dreams, trance or everyday reality - in which you hear the chthonic voices of the spirits.

Finally, I have to express my deep gratitude to Anne Hila for her shared passion for apocryphal magical manuscripts and her genuinely inspired transcription and translation skills, which she kindly offered so freely. Furthermore I want to thank José Gabriel Alegría for the many enchanting pieces of art he contributed to this release. To be able to collaborate with an exceptional artist like him is already a privilege; but to also meet a familiar soul in the study of goêtia – one working with the ink that draws, the other with the ink that writes – is truly rare. Equally my gratitude goes out to Hadean Press for being so patient with me in reworking and finishing these texts. Without their deep expertise, faith and partnership this book would not exist.

Read, understand, and reach for the work.

— Johannes Beer

Hadean Press Publication Schedule

October 10, 2020

Rosicrucian Magic. A Manifest.

Let’s begin with an exercise.

Think of an equal-armed cross, and yourself standing in its middle. You turn towards the North and begin to divest yourself of all aspects of your being that belong into this realm: your past, your roots and ancestors, your bodily strength and integrity. All things float back over this threshold that shield and contain: your skin, your bones, your blood. When there is nothing left to give to the North, whatever is left of you turns towards the East.

Here you continue the process: You hand over your familiar thought patterns, your intellect and mind, your ability to speak and utter, until you no longer remember your own name. Then, whatever is left of you turns towards the South and divest the aspects of yourself that belong here: Your future, that path leading ahead, your desires and fire, and all the chapters to come in your book of life. Now the little of yourself that still stands in the centre turns towards the West. Immediately the cells of your being that came from here begin to float back over the threshold of their origin: Your emotional weave, your traumas and delights, your love and anger, and the invisible substance from which – countless times without realising – you have created, destroyed and rebuilt that fragile sense of meaning.

What is left of you now, what finally returns to the centre, is nothing but a dim light. One breath of wind and your spark would be gone. Naked, vulnerable, almost unborn again, that is how your light hovers in the centre of the cross. – Then a ripple returns from the four quarters, as well as from below and above. And the spark that is an echo of your essence lights up, and unfolds into the form of a rose-bud. No roots, no stalk, no leaves, just a flower waiting to be awoken, hovering in the middle of the cross.

That is the mystery of the Rosy-Cross: For standing in its centre means giving up much of ourselves; it means no longer having the luxury of being orientated by the quarters, and neither by ones own hand, heart or head. The one who has become the rose knows no directions any longer, above and below have fallen into one. All that remains is the dim light shining forth, waiting to hear the echo of Divinity.

Speaking of Rosicrucian Magic is a folly for many good reasons. It’s best to be avoided to be honest. Most people – scholars and practitioners alike – quickly came to substitute it with terms such as Theosophy, Pansophy, Astronomia Olympi more rarely, or simply adepta philosophia. So if we dare to use these two often romanticised and rarely understood terms here bound into one – Rosicrucian and Magic – it is for one reason alone. Because, if properly understood, nothing describes the essence of the work better than this simple term. The four arms of the cross span the world, they uphold its necessary tides and tensions; the rose is our work.

We would like this term to be understood as referring to the practical magical legacy left behind by great adepts such as Johannes Tauler, Johannes Trithemius, Paracelsus, Jakob Böhme and many other, now nameless German mystics of the first and second century of the Protestant Reformation. We are precisely not referring to any occult order, any organisation known by seal and stamp, nor even any magical lineage. We are referring to a light that came through with these humans, shining in their works and words, and which, if we chose to, can guide us again today.

Rosicrucian Magic, as we like to apply the term, can be many things to many people, and yet, it is one thing above all: It is the magical work that ripples out from the rose-bud described above. Void of human motives, void of the ever hungry I, Me and Mine, void of roots and times passed, void also of eyes seeing a path.

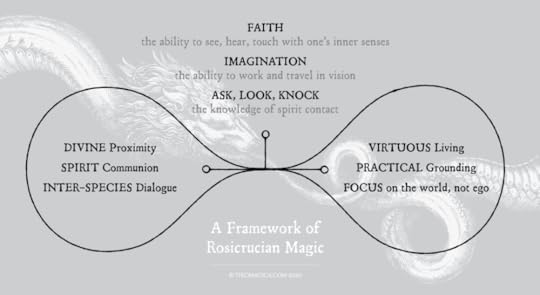

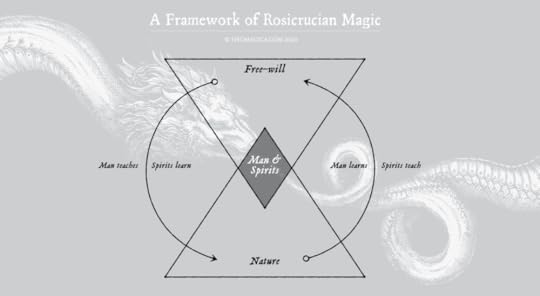

Rosicrucian Magic requires us to master three tools, which when used together from the centre of the cross, allow us to balance the fulcrum of being fully involved in the physical, as well as deeply present in the spiritual realm. It operates on the premise that everything is always present – or can be awoken – and that each thing created holds a spark of consciousness and presence of its own. Thus everything wants to be spoken to, and everything wants to be heard. Silence and listening are at the heart of this craft; just as learning how to not apply its power. If we wanted to condense it into a most simple framework – and this is the intent of this short text – it could look like the diagram above. The choices we make on the right, the world we encounter on the left, the fulcrum of our craft at its centre. Left and right necessarily bound into one, organically reacting to each other like the arms of the scale: You make a movement on the right, you feel its ripple on the left, and vice versa. Spirit work is everyday work. The scent of your will attracts beings alike. The impression of your deed creates a hollow for the spirits to follow. Always surround by a tribe, always surrounded by all facets of life. One word uttered, a million ears pricked. One arrow shot, a hive of spirits awaiting its impact. Rosicrucian Magic is born from the deep realisation that we cannot be part of this world, without forever changing it. None of us will ever walk over snow without leaving a trace. Rather, we have to come to terms with the fact that each of our acts is both mundane and magical, secular and sacred at once. Right at the same time, in every second, with every breath, we are being born from the outside just as much as from the inside.

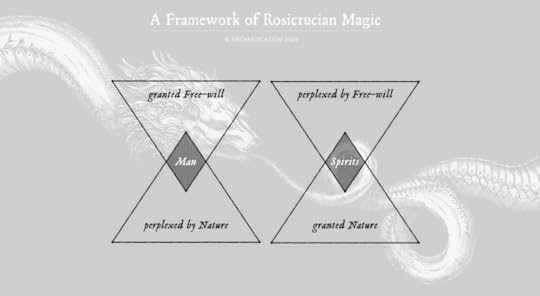

– If all of this sounds a little too abstract, let me invite you to meditate over the three diagrams below.

They condense much of the above into a pragmatic formula: As humans we are granted free will, and yet constantly perplexed by nature. As (e.g. elementary) spirits we are granted the essence of nature, and yet constantly perplexed by humans applying free will. – So what if we became both teachers and students to each other? What if humans came to see each act of applying their free will as a learning blueprint for the spirits around them. And what if we invited the spirits teach us about Nature on their own terms, in their own ways, rather than forcing our way through it with sheer will.

Rosicrucian Magic, as we like to apply the term, invites us to assume a deeply animistic worldview. One where we are not a distant observer or cool operator, but a swirling whirlwind of blind destruction - until we came to stand in the centre of the cross, silent, hands empty, heart open, waiting and ready for whatever will happen next…

August 16, 2020

On a Prayer relating to an unknown Rosicrucian Magus Ritual

Here is a mystical gem so good I had to share it with you. And here is how I came across it.

At the moment a longer essay is keeping me busy which will focus on an inofficial magus-degree ritual that emerged from the milieu of the Order of the Gold and Rosy Cross in the late 18th century. Central to this text, published in the spirit of the original Rosicrucians, is the motto ‘The True and the Good’ [Das Wahre und Gute]. In fact, the anonymous author states that together with the number 75 and the word Vaudahat this motto was one of the keys that identified the mages in their order who worked from within the sphere of Tiphareth. We will speak much more of this in the upcoming essay, which will be published online for free at the Holy Daimon Project, as well as possibly in a small print release.

In 1791, however, one of the men I most adore published a book of rather unusual prayers. Already back in May 2019 I shared his perls of wisdom on Prudence and Virtue. I am speaking of Carl von Eckartshausen (1752-1803), and for anybody who missed the introduction in 2019: Eckartshausen was a German mystic, philosopher, occultist and alchemist. Most often today he is known as the author of the classic The Cloud Upon the Sanctuary (Die Wolke über dem Heiligthum, 1802), which influenced the early Golden Dawn and Aleister Crowley specifically. However, Eckartshausen also was a highly successful lawyer, one of the youngest ever privy councillors at the Munich Court, a Secret Archiver and member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. While he is listed as an early member of Carl Weishaupt's Order of the Illuminati, he quickly left it again and became a prominent critic of the order. His own research mainly delved into mystical, kabbalistic and numerological studies. However, most of all Eckartshausen was obsessed with understanding the human heart – and how to refine it.

And this is where the above mentioned prayer book comes into play: Under the unassuming title ‘God is the Love most Pure’ (London: Hatchard, 1817; original: Gott ist die reinste Liebe, 1790) and over almost three hundred pages Eckartshausen masterfully wove his extensive occult knowledge and hermetic-rosicrucian meditations into what equally could be read as reflections of a Christian natural philosopher. Much to everyone’s surprise, the book turned into a stunning success and saw a huge amount of reprints well into the late 19th century. (The photos in this post are taken from a 1799 reprint, personally bound in leather as a luxurious travel-edition for someone by the initials ‘T.P.’) – Well, and it is in this book, which was published roughly at the same time of our inofficial magus-grade ritual, that we come across a prayer titled ‘On the True and the Good’ (Über das Wahre und Gute).

In the following I am provding my personal translation of this short mystic prayer, followed by the German original. Additionally, I want to add the following few remarks: Wherever you read the word ‘knowledge’ in English, the German original is ‘Erkenntnis’ which equally translates as gnosis. Equally, where you read ‘mind’ or ‘wit’ both terms are translations of the German ‘Verstand’ which holds a stronger connotation to the idea of ‘understanding’ and even ‘prudence’ than the English ‘mind’ might do. Becoming alike to the divine or angelic mind is a key idea of angelic theurgy which we explore in depth in Black Abbot · White Magic. And finally, in a mystic text written by an adept, such as this succinct prayer, every word and its position have been chosen deliberately. Thus if you intend to delve into the mystical layer of the prayer, I suggest to read it slowly. And maybe read it again.

Here is to the True and the Good in all of us – and in a time when we can all need some.

LVX,

Frater Acher

May the serpent bite its tail.

The influence of Eckartshausen and his work extended to all of Europe and was especially perceptible in Germany, England, France and Russia. His system, which is nevertheless in no way innovative, is testimony to a scope and a depth of vision that command admiration. This richness makes him, next to Franz von Baader, one of the most representative gems of Christian theosophy in the last two decades of the German 18th century. (Jaques Fabry, Eckartshausen, in: Wouter Hanegraaff (ed.), Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism, Brill 2006, p. 328)

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

On the True and the Good.

When I look around, my God! and behold the beautiful creation! when I consider your wise commands, All things call to me that truth and goodness are the pillars upon which heaven and earth rest.

It is therefore necessary, O God! that I know what is true and good; and it is this important subject that I will reflect upon today;

Truth and goodness are only you, and true and good is only what you are. Love in knowledge is the good, and love in practice is the true.

Truth and goodness must be united, for truth is an object of knowledge, and goodness is an object of will: - and what would knowledge be without will?

The mind and wisdom of your angels, O Lord!, come into being through the union of the true with the good! without this union is only error and falsehood.

Truth, O God! therefore is you, and true is all that you are: so if I seek truth, I must seek you, become alike to you.

You gave me, my God, will and wit – the wit to know, the will to want what I have come to know. You, my God! are goodness: Everything that has being [Ger- man = Dasein] is good, and everything true that comes close to the exercise of this goodness. When I recognize your goodness, and this knowledge passes into my will, then your goodness becomes visible through me, and my action is true.

So let me realise, my God!, that I must combine the good with the true, and grant me your wisdom so that I may have understanding and will, and do not make me equal to the wise men of the world who have only science instead of understanding, and desire instead of will; you turn my will into the vessel of the good, and my mind into the container of the true. Amen.

Über das Wahre und GuteWenn ich umhersehe, mein Gott! und die schöne Schöpfung betrachte! wenn ich deine weisen Anordnungen erwäge, so ruft mir Alles zu, dass Wahrheit und Güte die Stützen sind, worauf Himmel und Erde ruhen.

Notwendig ist es also, o Gott!, dass ich wisse, was wahr und gut; und über die- sen wichtigen Gegenstand will ich heute nachdenken;

Wahrheit und Güte bist nur du, und wahr und gut ist nur das, was du bist. Die Liebe in der Erkenntnis ist das Gute, und die Liebe in der Ausübung das Wahre.

Wahrheit und Güte müssen vereinigt sein; denn Wahrheit ist ein Gegenstand der Erkenntnis, und Güte ein Gegenstand des Willens: – und was wäre die Erkennt- nis ohne den Willen?

Der Verstand und die Weisheit deiner Engel, oh Herr!, Entstehen durch die Ver- bindung des Wahren mit dem Guten! ohne diese Verbindung ist nur Irrtum und Falsches.

Wahrheit, o Gott! bist also du, und wahr ist Alles, was du bist: wenn ich also Wahrheit suche, muss ich dich suchen, dir ähnlich werden.

Du gabst mir, mein Gott!, Willen und Verstand – den Verstand, um zu erkennen; den Willen, um das zu wollen, was ich erkannt habe. Du, mein Gott! bist Güte: Alles was ein Dasein hat, ist gut, und Alles wahr, was der Ausübung dieser Güte nahe kommt. Wenn ich deine Güte erkenne, und diese Erkenntnis in meinen Willen übergeht, dann wird deine Güte durch mich sichtbar, und meine Handlung ist wahr.

Lass mich also erkennen, mein Gott! dass ich das Gute mit dem Wahren verbin- den muss, und gib mir deine Weisheit, damit ich Verstand und Willen habe, und lass mich den Weisen der Welt nicht gleich sein, die statt Verstand nur Wissen- schaft, statt Willen nur Begierde haben; schaff du meinen Willen zum Behältnis des Guten, und meinen Verstand zum Behältnis des Wahren. Amen.

May 30, 2020

Trithemius and the Magic of Free Will.

Integrity, some say, is what you do when nobody is watching. And G*d, others say, is always watching. Yet neither of them, from a magician’s perspective, is hitting the mark. A fire has no centre and no periphery. A sea’s heart is everywhere and nowhere at once. The entire being of a storm is embedded in each gust. A storm is no more or less storm in the squall that touches you or her.

In the same manner, I suggest, a magician should think of themselves. Not as a being installed in skin, but as a cloud of consciousness, expressing all of itself in each act. Whether we grant significance to this act or not is entirely irrelevant. For the significance that matters resides beyond the sphere of the living. It is a different place altogether. One where our biggest decisions are just equal to our smallest. Where each mortal’s step matters, and at the same time doesn’t. Where fates are woven by a glance and a cue, and yet weaves continue eternally. On this level, we humans too are a natural force. Each one of us a tiny portion of it. And this natural force called humanness can only be experienced when it encounters the rest of the world. Malkuth. Now, what determines this force’s quality and nature is entirely up to us. And that is why this force is so magical and unique; it carries a seed nothing else in Malkuth was granted. The seed of free will. And the only way to experience this force that we are, and this seed that we were given, is to watch a human applying themselves against the world. Free will is nothing at all - unless we awaken it, by holding ourselves up against the world. It is in the contact between each human and the world, that the game the gods once began will end. Tikkune.

How we hold ourselves is everything - not because G*d is watching, but because there is nothing else that we are. We are empty from within. Just like fire, oceans and storms are empty from within. There is nothing other to them than being fire, being oceans and being storms. Each of their expressions, each time we encounter them, they are perfectly expressed. And so it is with us humans. Our way of being, our way of seeing, the way we decide to hold ourselves towards the world. That is all we have. Because it forms the prism through which flow all of our acts. Each breath. Each step. And there is nothing else.

For a magician this should not come as a surprise? For isn’t this how we came to think of the spirits - of storm demons and chthonic sleepers, of hive-beings and angelic structures. None of them are mounted in skin. All of them seem as fleeting as free. They are able to come and go, to apply themselves against the world and to withdraw from it, like a magical tide. All their myths and personas over centuries were not made up by who they are deep down in their insides, by what they were born from, or what they strive towards - but only by how they behave towards the world. Each being, may it be angelic, human or otherwise, is defined by its encounter with the world. Without it, we are nothing but potential enshrined. The world is the divination bowl, filled with black waters, into which the gods stare, and see us.

Johannes Trithemius believed evil angels were G*d’s way of testing our free will. According to him, demons held no agency in themselves, unless we granted them access to the seed that was given to us: free will. Integrity according to such a worldview is nothing we strive to achieve for G*d or others. It is not at all a social good. But it is the most essential of all magical capabilities: To let each of our decisions count, as if we were standing at the scales of Ma’at. And yet not to become self-judging or orthodox, but to stay connected to the flowing tides of life, like fire does. What an exquisite challenge.

The ‘white magic’ I rediscovered in the works of Johannes Trithemius and his alleged teacher Pelagius is like nothing I have ever encountered before. It is magical for it focusses entirely on how we apply our free will towards the world. It teaches the handling of magic as a force, not for escaping, but for pulling closer into the world. And yet Trithemius’ ‘white magic’ is maybe even more mystical than it is magical. Because it strips away anything unnecessary. Like most mystical paths, it appears Saturnian towards the world, and is unconditional in its demand towards how we show up to the world.

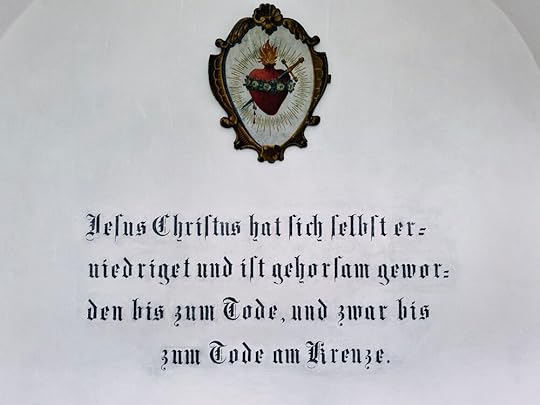

I was sitting on a rusty bench in the courtyard of an old abbey as I reflected on the above. The people here opened an exhibition today called ‘Tugendreich’, that is German for ‘rich in virtues’. I actually like both etymologies at lot, the one of the German word as well as the English: The word virtue derives from the Latin word for man (vir). However, it must not be read as referring to some kind of manliness, but rather humanness. A human, according to the root of the word, is a being that knows how to hold on to virtues. The German word, Tugend, on the other hand stems from an old root that expresses the idea of ‘being good enough for’ (taugen). Thus, it is only through virtues that humans become good enough for this world.

Believe me, this was a wonderful place to sit and think. And maybe take photos, as you can see below. While I have significant personal problems with Catholicism, my heart recognise this site as a venue full of integrity. The nuns who lived here, whatever they did, however flawed they were themselves, they for sure applied themselves beautifully towards the world when nobody was watching. For they lived in strict conclave for hundreds of years. And yet they left something behind, that I can still hear singing, beautifully, when I only silence myself enough.

In the end, and as we see in the world around us today in blinding light, little in life matters as much as virtues do. Now, if like me, you were born with rather brittle chivalry, falling over to the side of your vices more often than not, then welcome to the conclave. I reckon, all of this can change. Right now. For there is no better way to draw out from ourselves the virtues we didn’t even know existed, than by seeking real-life communion with angels. White Magic.

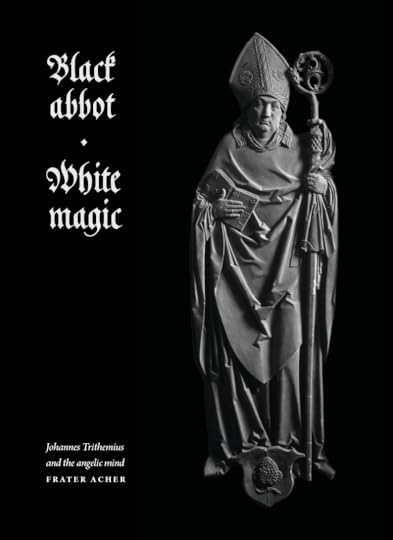

Black Abbot · White Magic - Johannes Trithemius and the Angelic Mind

May 22, 2020

Black Abbot・White Magic

Next week, on Wednesday 27 April, Scarlet Imprint will open preorders for the second volume of the Holy Daimon Cycle, Black Abbot · White Magic: Johannes Trithemius and the Angelic Mind. Meanwhile Jose Gabriel Alegría Sabogal’s stunning artwork has traveled safely from Lima to Cornwall (see a clipping above), and Alkistis Dimech’s skilled hands are putting the finishing touches to a text that is indeed very close to my heart.

When I first began to read about the history of Western magic, almost thirty years ago now, I remember how upon first glance his name seemed strangely familiar: Johannes Trithemius. The name appeared like a memory, like a tide returning, promising to bring back something that in reality was lost forever. And so it seemed for a very long time. Irrespective of how much I tried to research the man - his magical self seemed shy and elusive, its marks missing from the few German biographies I could get my hands on.

Many years have passed since. Time enough to learn that life has a strange kind of irony: Just when we give up on a dream, when it escapes our sight and maybe our memory too, the long locked door that leads towards it can spring open. Little did I know when I visited the first Leipzig Grimoire Conference in 2018 that it would lead me to reencounter Johannes Trithemius - and this time, finally, he brought his magical self with him.

Black Abbot · White Magic is an invitation to accompany me through this open door - and to meet Trithemius through the lens of his own magical writings. The role of his legendary teacher, Pelagius Eremita, is critical in this context.

Within the field of ritual magic in the 15th century new developments are essentially due to one man, Pelagius of Majorca, who in the second half of the 15th century does not hesitate to break the common law of pseudepigraphic attribution (to Solomon, Hermes, Toz the Greek and other old authorities) to indulge his own speculations. (Julien Véronèse, 2006)

As scholars have previously called out, and as our book goes on to show in great detail, the man Pelagius Eremita never existed. The figure is nothing but a complex ruse - imagined, birthed and buried by Trithemius himself - all in a daring attempt to fulfill his lifelong dream of founding an authentic ‘theologia magica’, a form of white angelic magic. Thus it is through the alleged Majorcan hermit Pelagius that we gain access to Trithemius’ personal view and direct experiences of a magic filled with mystical integrity and angelic presence. Furthermore, we begin to see that without the writings of Trithemius-Pelagius - that is, without the intercession of an imaginary figure - the entire modern tradition of Western magic would not be the same.

I have provided a brief overview on the content of Black Abbot · White Magic here. Also, in a previous post we took time to familiarise ourselves with the slightly overused term 'white magic' - and to position it in the way that it will be used in the book, and how I believe it was intended by Trithemius. Finally, the link to Scarlet Imprint’s pre-order page will be live on Wednesday 27 April.

— May you enjoy the journey as much as I did. And even more importantly: may your practice be as much inspired as mine was, by the light that shines from the Janus face of Johannes Trithemius and Pelagius Eremitae.

Finitis modum dedimus ad infinita.

We show a way to the infinite.

— Johannes Trithemius, Polygraphia

April 18, 2020

Hellboy and a 17th century White Grimoire.

The following is an excerpt from a book currently being birthed. Its main theme is the careful examination and practical restoration of an original 17th century ‘white grimoire’, focussing on the use of a liturgic bell designed to call the seven Olympic Spirits, as well as through their mediation, one’s HolyDaimon.

Because this short chapter stands somewhat outside the rest of the text, and because the magic discussed seems relevant to our current time, I decided to share it here in advance… If you want, please wish me luck with my inquiry to Mr.Mignola to use some of his art in the final book.

Stay safe and healthy, my friend.

LVX,

Frater Acher

Motse ha o na sehlare: sehlare ke pelo -

Power is not acquired by medicine: the heart is the medicine

— Morena Mohlomi, 1720-1815

(…) Before we dive into the maze of the now famous Olympic Spirits, we shall take a lesson from a rather different source. Mike Mignola in his 2002 Hellboy story, The Third Wish, offers a most profound lesson on the use of sacred paraphernalia in magic. As usual with Mignola’s original comics, his stories are an expression of both, his astonishing artistic genius, as well as the extensive research he has done before he even puts the pen down. In The Third Wish Hellboy encounters the wise African medicine men Mohlomi. The latter figure is a reference to the authentic Morena Mohlomi, an 18th century African chief of the Bakoena tribe, and respected to this day beyond the boundaries of Lesotho as a wise philosopher and medicine man.

If you have the chance, we strongly recommend reading the original stories contained in Volume 3 of the Hellboy Library edition. For all others, we thankfully offer the following summary by Thom Hardman:

Mohlomi offers to Hellboy a protective talisman in the form of a bell, he claims it is his 'medicine' and that it will keep him safe. This bell, seemingly imbued with magic, is crucial to saving Hellboy's life on a number of occa- sions, even miraculously reappearing after previously being eaten by a shark. And it is on this subject that the words of the real world Mohlomi take on a deep significance for Hellboy's story.

The story goes that when a young, ambitious Moshoeshoe first met with Mohlomi, he requested magical assistance or medicine from the wise man, to help with his campaign to become a powerful chief. To this Mohlomi responded with the aforementioned quote that “the heart is the medicine.” As Hellboy lies dying on a forgotten and uncharted island; his bell lost, his heart impaled and his own blood congealing into the demonic form which he fears lies dormant inside him, Mohlomi returns to speak with him again.

In this meeting between life and death, Mohlomi hands the missing bell back to Hellboy, stating that “nothing's lost”, in doing so restoring Hellboy to life and giving him the required power to defeat the nightmare version of himself. It is not however the bell, not the medicine, that gives Hellboy this power, but it is the heart and conviction that Mohlomi returns to him. Hell- boy reaffirms that he will fight to the last against his supposed destiny, rather than a magical trinket, Mohlomi restored his heart.

The role Mohlomi takes on in Mignola’s story is the personification of a spirit guide, thus an echo of the qualities of his real-life antetype. However, Mignola’s Mohlomi appears to Hellboy two hundred years after the former’s death. Thus in the story Mohlomi appears as an ancestral spirit, a being traversing both sides of life of death. As mentioned by Hardman, it is critical that after receiving Mohlomi’s ‘medicine’ in the form of a magical bell in The Third Wish, Hellboy encounters the wise spirit again in the 2005 story The Island. Designed by Magnolia as a counterpoint to the easily digestible Hellboy movies of the time, this episode was meant to charter much of the complex cosmological back-story of our antihero from hell. Mohlomi’s spirit appears to Hellboy in the very moment as the latter lies defeated, with a pierced heart, bleeding out, on the threshold of death. Upon retrieving the magical bell from Mohlomi again, Hellboy’s personal and deeply sinister destiny is fully revealed to him. It is then that Hellboy realises that in order to not fulfil the fate from hell destined for him, he will need to lean against his own blood and into the heart-space healed by the sound of the magical bell. Finally, with the restorative forces of Mohlomi’s medicine, Hellboy overcomes his own shadow and the seed of destruction contained in the ‘right hand of the devil’.

The heart is the medicine, the real-world Mohlomi wisely said. Two hundred years after his death, through Mignola’s inspired vision, this medicine took on the form of a small liturgic bell, passed on from beyond death by an ancestral spirit to an antihero from hell. Even more than a tool of protection, Mohlomi’s bell is a tool that offers restoration of the heart.

Clearly, none of us is Hellboy. Nobody’s blood in this world carries the memories of hell. And no one of us is adorned with the ‘right hand of the devil’. Yet, our human curse also often has been likened to a gift of the dark lord. For our curse, as well as possible blessing, is free will. The figure of Mohlomi in Mignola’s stories is a wonderful symbol of the living promise that magic holds for each practitioner: Whatever mess we have gotten ourselves into, whichever one-way street we got stuck in, however dim our heart-space has grown, there is a medicine waiting for us. There is a sound out there somewhere, a call of a bell that will protect us and restore us to a better version of ourselves. It is this bell’s call that turns our blood from a bond with hell, into a river of freedom.

As we will now look at the central operation of our 17th century text, remembering Hellboy’s experience of the wise Mohlomi is advised. For it is a similar promise we encounter in this grimoire of white magic: A pathway towards a sound that will tie us closer to our holy daimon, to our protector and guide, the being that will help us hold on to our noble self, however dark the night we stand in.

(…)

March 27, 2020

Thoughts on White Magic as a Practice

White magic. The term is so over used and yet ill defined. My upcoming book will be called Black Abbot ✷ White Magic, Johan Trithemius and the Angelic Mind. And as I am realising now in hindsight, over the last fifteen years my own practice and study has been dedicated entirely to restoring and reactivating a magical current that best is summarised under this term. So it seems an opportune moment to sharpen the saw on how I will be using this term.

Carlos Gilly famously called the Arbatel the first book of white magic. That of course is a tongue-in-cheek claim. For we know, nothing in magic appears out of nowhere and most things had been discovered before, only to be slowly swallowed again by the rolling tides of time. Many works of magic have paved the way to the expression of ‘white magic’ as we encounter it in the Arbatel. And yet, Carlos Gilly is precise that possibly none of these had gone into print before. So we can agree that the Arbatel fairly can claim to be the first printed book on white magic.

The relatively unknown series of manuscripts that had preceded the Arbatel only be a few decades, and that are essential to the form of magic we encounter in the latter, were in particular the writings of a cryptic author by the name of Pelagius the Hermit. It is these manuscripts and their close entanglement with the figure of Johan Trithemius that we will explore in the forthcoming book. — So as I am using the term ‘white magic’ I am standing knee-deep in this magical current that first reemerged in the early 16th century Germany. Accordingly in these current’s waters, the easiest way to define white magic is to consider it the last step a practitioner of the magical art can take, before they enter the cloud of unkowning. That is, before they become a mystic.

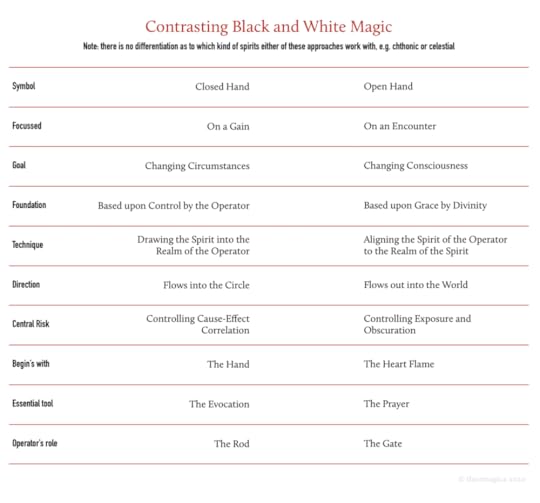

But I’ll make this a little easier, and a little more precise for us. For the tradition I am talking of, we could contrast black and white magic according to the following qualities. What is critical to embrace though, is that neither of these terms contain an ethical or values-based judgement. In essence, both terms relate to the non-colours of black and white and their specific qualities: For black to absorb all light on its surface, and for white to reflect all of it back into its circumference.

You see, no one of us lives their life with hands open all the time. The beauty of life is following its tides: opening and closing our hands, breathing in and out, taking and giving. The imbalance in Western magic, in my humble opinion, is that at least since the Early Middle Ages our current had turned into a (literary) tradition that was all about closing one’s hand. It had devolved into a substitute pathway towards power acquisition and economical growth. That is why until this very day, every narcissistic soul who insists that life keeps on owing them, feels naturally at home in the genre of the Medieval Grimoires. For centuries Western Magic has turned into the spiritual equivalent of the Crusades or the Spanish Reconquista: man’s feeble attempt to take back a realm they believed to be their birth right. Failing to realise that what lies behind such spiritual warfare is one’s own deep ignorance, the essential inability to understand, appreciate and co-exists with otherness. The ability - for some time at least - to walk through life, with both hands open.

That is what ‘white magic’ is to me. A cure. A rebalancing of the poison. A necessary lent and diet from the constant craving of power acquisition that has become synonymous with our Western Tradition of Magic. It is a return to work in true partnership. And for that it takes a lot of preparation. Not (only) in technical skill gains, but much more essentially in preparing and drawing out again the raw light of our heart-flame. We have to turn ourselves from the the rod that aims to direct the world as a donkey, into the the gate that is open to channel the tide wide without breaking itself. What a marvellous goal and journey! And we shall keep humbleness at our side at all times. For that is what white magic is about at its heart: the humbleness to realise that the vessel our human spirits have been poured into at birth, is one of the smallest containers in creation. Our part of the weave literally is tiny. It is true: we humans are tiny spirits, and yet mighty in our versatility. One could argue, we are the Swiss Army knifes of spirit vessels. We are unintentional utility personified, amongst a world that is born from divine purpose. We are free will. Thus, we are the best at inserting ourselves into any crack and fissure of creation, and breaking it apart for good. Without really knowing why we have done it in the first place. We are like children, feverishly excited when witnessing our own impact on the world. But different to a child, we gain the tools and qualities of a magician only as adults. White magic, therefore, is about owning our fair share. It is about walking slowly, very slowly indeed. Just to realise how much power we can unfold with each step, if only placed in true divine intent.

March 18, 2020

Forestedness - or gaining control by letting go

This is a repost from 2013. Seven years have past. Not a lot of time in a forest. And yet this spirit’s voice called me back, as it seems so relevant in the days of Covid-19. Here is to all of you, fellow trunks and crowns.

LVX, Frater Acher

So I heard a voice. And the spirit said to me:

“A forest rests on many trunks.”

You have to understand... I just came out of several weeks of extremely demanding work that ended in getting a cold while on business trip in London and returning home early. While at home I juggled time in bed, time inhaling and time on conference calls, arriving at Friday night feeling completely banned from myself and exhausted. I guess we have all been there?

So this was the state I started to recover from when the spirit spoke to me about the nature of the forest resting on a many trunks. At the same time I heard its voice the spirit also showed me an image. The image showed a drawing of a huge unified forest crown supported by many trunks which again unified into a single foundation of strong roots... When the voice and image appeared, I closed my eyes, gazed at the image on my mind and everything fell silent. I realized there was a beautiful, a powerful message hidden in this simple sentence. A forest rests on many trunks. A forest rests on many trunks ...

My first reaction was an intuitive one. It was a feeling of deep relieve. Only then did I notice there had been a place within me that had held its breath for a very long time. Only now did it start to exhale. And only now, looking backwards do I realise: boy, did I need fresh air! The second reaction was the thought: How wonderful to be part of a forest! How wonderful to blend in. How wonderful to be surrounded by trees, to disappear into this darkness of green moist and bark, of animal sounds and roots deep down in the earth and crowns that stretch out like blankets below the clouds....

Instinctively the voice of the spirit brought me back to a place I had lost for a many weeks: a place of connectedness, of togetherness, of forestedness. It was a place where I shared joint roots and a joint crown, a place where there was no need to think or speak or act at all. A place where I just needed to be: A forest rests on many trunks. And wether I wanted or not, I also needed to acknowledge the flip-side of this forestedness: I was only one of many, intricately connected, yet equally bound by the bonds that embedded me into this forest of life and magic, of day and night, of experiences inside and outside of myself.

So the voice of the spirit at the same time managed to bind me and set me free. By giving me a simple image and a single sentence it changed my place and brought me back to where I longed to be. I lay there, eyes closed, still looking around at where I found myself...

Now I am sitting on a plane flying into another week full of meetings. I still see myself as a tree in the forest, holding up only a tiny fraction of the huge green unified crown that spans above all of us. What I still remember from the moment when the spirit spoke to me is this: Use control wisely and sparingly. Be gentle when using force to achieve what you think might be the goal. Mainly because you could be terribly wrong - and maybe are just pushing yourself and others closer to the edge...

In a forest night falls like a wave and day emerges slowly, light searching for its way through the branches, slowly warming the ground. Few things in a forest happen immediately, and most things take a lot of time. Many unknown creatures dwell in a forest. And knowingly or not each tree contributes to building their nests and trails and nutrition. Being in a forest reminds me to be respectful towards the things I do not see, I do not know, yet which contribute essentially to the balance I thrive on.

Change happens organically in a forest: It might be triggered without notice, an animal bringing in an unknown seed, a colony of ants moving in carrying an unknown fungus in their eggs, a storm or a fire breaking down a large section of trees allowing the wind and the sun to touch the ground for the first time after decades... Most of these changes are completely beyond control of the forest. And it doesn't aim to control. Instead, its power lies in its ability to adjust, to transform and embrace the change that is brought upon it. A forest doesn’t cling. A forest has no emotional self when it comes to letting go nor when it comes to accepting new things into its realm. Intruders might starve to death in a forest and produce new soil or they might eat large parts of the forest and produce new soil anyway. Either way, it is the forest that will prevail - because it rests on many trunks.

The only forest that dies is the forest that has become overly rigid. Rigidity, the inability to flex and change and adjust to one’s environment is introduced to the forest by man when biodiversity is reduced and wood is being farmed rather than allowed to spread and grow organically in families...

So this is the advise I am taking with me, allowing it to cling on to me like a faint scent on my clothes: all the diversity, the chatter, the chaos that I experience and sometimes hardly can cope with - it is exactly this seeming chaos that will make us strong in the long-run. Wether we like it or not, it is the mess emerging from the periphery, slowly but surely leaning against our human will, that keeps us from becoming rigid. That keep us human. For what looks like chaos on the outside, is a melody from within. It is an essential part of our forestedness.

A good friend once said to me: ‘Everything will be good unless you have a plan.‘ I guess that is true for humans and forests alike? So if a being as beautiful and perfect as a forest doesn’t rely on control to become what it is, but on flexibility, on sensing changes early and adjusting to them accordingly - well, why couldn't I?

Frater Acher's Blog

- Frater Acher's profile

- 69 followers