Rick Wayne's Blog, page 40

August 5, 2019

No Excuses

We are never as creative as when making excuses for why we can’t be.

Akira Kurosawa, for those who don’t know, wasn’t just one of the greatest directors in Japan. He was one of the greatest directors of the 20th century and a founding voice in the cinematic arts.

The joke goes, he was every Western director’s favorite artist to steal from. His 1958 black-and-white film The Hidden Fortress was direct inspiration for George Lucas’s Star Wars, both the original film and The Phantom Menace — and that is putting it charitably.

It went both ways, of course. There’s a story about Kurosawa, certainly apocryphal but I’m sure with a grain, that tells of his assistants running to him one day in a fit.

“What’s wrong?” he asks.

“Sensei,” they say, “The Italian, Sergio Leone, has made a movie called A Fistful of Dollars, and it is Yojimbo!”

“Yes,” the master says coolly. “I heard it was like Yojimbo.”

“It is not ‘like’ Yojimbo, sensei,” the assistants object. “It IS Yojimbo! You must do something.”

“No, no,” he waves them off. “We will do nothing.”

“But…” the assistants stammer. “But why, sensei?”

“Because,” the master says, returning to his work. “Yojimbo is Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest.”

(In fact, a case was brought, although it seems to have been settled out of court.)

In Japan, once you reach master status, you’re expected to speak tersely and with zen-like wisdom about your craft. Kurosawa had a lot to say about art and creativity, but he seemed almost offended, certainly annoyed, by excuses.

Take the following quote, one of my favorites, given in an interview near the end of his life.

“The thing I stress the most to the aspiring directors who often come knocking at my door is this: ‘It cost a great deal of money to make a film these days, and it’s hard to become a director. You must learn and experience various things to become a director, and it’s not so easily accomplished. But if you genuinely want to make films, then write screenplays.

All you need to write a script is paper and pencil. It’s only through writing scripts that you learn specifics about the structure of film and what cinema is.’ That’s what I tell them, but they still won’t write. They find writing too hard. And it is. Writing scripts is a hard job.

The tedious task of writing has to become second nature to you. If you sit down and write quietly the whole day you’ll have written at least two or three pages, even if it’s a struggle. And if you keep at it, you’ll eventually have a couple of hundred pages. I think young people today don’t know the trick of it. They start and want to get to the end right away.

When you go mountain climbing, the first thing you’re told is not to look at the peak but to keep your eyes on the ground as you climb. You just climb patiently one step at a time. If you keep looking at the top, you’ll get frustrated. I think writing is similar. You need to get used to the task of writing. You must make an effort to learn to regard it not as something painful but as routine. But most people tend to give up halfway.

I tell my assistant directors that if they give up once, then that’ll be it, because that becomes a habit, and they’ll give up as soon as it gets hard. I tell them to write all the way to the end no matter what, until they get to some sort of end. I say, ‘Don’t ever quit, even if it gets hard midway.’ But when the going gets tough, they just give up.”

I spent the last couple years finishing FEAST OF SHADOWS for this exact reason. It’s an odd book. As I noted in a recent interview, it’s not like my others, and I will probably lose readers. But I needed to finish it. Not because it was easy. Because it was hard.

It sounds so lofty and artistic. “I have to finish it.” But it’s not. It’s the opposite of that. I can think of nothing more mundane than sitting down and finishing your work.

There’s a kind of paradox, as the master notes. Everybody wants to rush to the end, but to write quickly, you need to write slowly. That is, making a living at the craft — forget completely about fame, which is not a reason to do anything — making a living requires that you produce swiftly at high quality, but you can’t do that until you’ve reached a certain proficiency, and you can’t reach proficiency except by practice, practice, and more practice.

That doesn’t mean writing words. Poets make words. Novelists make novels. Practice means making novels, complete novels — or complete films, as the case may be, versus taking pictures or making snippets.

Not that you’re a dilettante if you’ve yet to finish a creative project. But you might be.

No one writes solely for money or solely for art. I’m not sure anyone who’s tried ever produced anything worth reading. (A good story, one that resonates, is one written to be read rather than to exist as an object unto itself.)

No one is born a novelist or film-maker either. If you expect to be any good at it, you have to suffer the hard bits. That’s where you learn.

The good news, Kurosawa tells us, is that if you’ve never finished a project, or have yet to try, it’s not too late.

In 1988, famed director Ingmar Bergman released his memoirs, called “The Magic Lantern,” wherein he admitted “I probably do mourn the fact that I no longer make films.”

Reading this, Kurosawa sent him a short letter:

Dear Mr. Bergman,

Please let me congratulate you upon your seventieth birthday.

Your work deeply touches my heart every time I see it and I have learned a lot from your works and have been encouraged by them. I would like you to stay in good health to create more wonderful movies for us.

In Japan, there was a great artist called Tessai Tomioka who lived in the Meiji Era (the late 19th century). This artist painted many excellent pictures while he was still young, and when he reached the age of eighty, he suddenly started painting pictures which were much superior to the previous ones, as if he were in magnificent bloom. Every time I see his paintings, I fully realize that a human is not really capable of creating really good works until he reaches eighty.

A human is born a baby, becomes a boy, goes through youth, the prime of life and finally returns to being a baby before he closes his life. This is, in my opinion, the most ideal way of life.

I believe you would agree that a human becomes capable of producing pure works, without any restrictions, in the days of his second babyhood.

I am now seventy-seven (77) years old and am convinced that my real work is just beginning.

Let us hold out together for the sake of movies.

With the warmest regards,

Akira Kurosawa

Start. Finish. No excuses.

[image error]

Feast of Shadows is available here.

August 4, 2019

(Fiction) Knock Knock Knock

[image error]

With his dying hand, Wilm left me all his worldly possessions. His creditors took the bulk, including everything of any real value, although I understand it covered less than one tenth of his balance. I was allowed to keep a small sum, which I passed to his child, and some of his personal effects, which I kept for myself. These included a number of books and letters stuffed into a large wooden stationery box that folded out to make a traveling desk, complete with shelves, drawers, quills, ink, blotters, wax, seals, paper, envelopes, and so forth, none of which were easy to come by. While waiting for Wilm’s estate to close, I continued to receive his mail and used the contents of the box to inform both his irate creditors and those seeking his assistance of his unfortunate yet heroic demise. One letter in particular struck me, from a man of some importance, an Austrian noble. I recognized in his oblique words a genuine desperation. In those days, in society at least, one rarely said what one meant outright. One demonstrated wit and grace—superiority, even—by the light touch of one’s euphemisms. This was especially true of anything unseemly. Young women did not have abortions, although we most certainly had sex. If the untoward resulted, we “went to the country” for a season, or to “take the waters” at some out-of-the-way hot spring, only to return rosy and rejuvenated months later. The problem, of course, was that meant one could not actually take the waters without someone supposing the worst. Hence the obsession with appearances, and on being seen. One’s only defense against rumor and innuendo was to act as openly and ostentatiously as possible so as to leave the smallest margin for supposition—to invite an entire train of followers to take the waters as well, for instance, and to finance their participation. Invitations thus flew about hither and thither among the idle class as they each sought escape from the very eyes on whom they nevertheless depended.

Wilm had been invited to winter at the nobleman’s ancestral home, which was described at length as a sportsman’s paradise. In fact, a full two-thirds of the four-leafed letter was devoted to its “sylvan slopes dappled with fishing ponds and forest groves, each thick with winter game,” with the final third quickly mentioning that, while he was there, he might perhaps also attend to “certain other matters of which you are an acknowledged expert”—meaning the occult. I responded to the letter with the news, as I had all the others, but added that I had “worked as Mr. Castleby’s assistant for several years” and that I was in possession of his notes and artifacts, and although I had not his skill and experience “in the matters of which you speak,” that my services were available, had his lordship need of them. The reply was swift, which is to say came within a matter of weeks. A carriage had been dispatched, I was told, and would arrive within days of receipt of the letter, which had traveled ahead by mounted messenger. And just like that, I was employed as a dabbler, the first ever work for which I would receive a salary.

I made no attempt to conceal my gender, but neither did I expressly reveal it, which caused considerable consternation upon my arrival. I had hoped to be saved by the grandeur of the white owl, which had taken to perching near me, but to no avail. My lord announced after tea that I was to be sent away first thing the following morning, and he would have done if not for a heavy snowfall that obliged the better part of a week’s stay, during which time the facts of the case became known to me. It was a mild haunting, as they go, but harrowing all the same—full of the usual patent terrors: doors that wouldn’t remain closed, ghastly sounds emanating from inside the walls, and of course the knocking. Knocking, knocking, interminable knocking. It woke you at all hours, rising in intensity with each unanswered bout until at last it was like a hammer on the door, rattling the hinges and echoing through the house, louder and louder until someone had the strength to answer it—and were greeted by nothing. Some nights it would start again an hour after you returned to bed. At other times it would resume before you crossed the foyer, or even the very moment the door was shut, immediately angry, as if the door that had just been opened was not the correct one.

And that was the clue. I suspect Wilm would’ve gotten it right away. It took me a fortnight of frustration and study. Before the snows abated, I suggested to my lord that I be allowed to stay, at least until he found a suitable replacement. I would draw no salary, I said, unless my interventions were successful. He agreed, reluctantly, eyes haggard from lack of sleep, and I set to work. Some weeks later, after a terrible night that saw his wife and children huddling in a corner, I asked my lord and his family to leave the house and mentioned, as they packed into a covered sled, that I might do it quite a bit of damage in their absence, but that in the end, I would either drive the apparition away or be taken by it. I think by then he had lost all faith in me, as the owl had several days before, and intended to have me arrested as a charlatan upon his return. But just then, he had little choice. I watched until they were all out of sight, then turned to face the house alone.

It was a mistake. The truth was that I did not, in fact, know what I was doing, and the flight of the occupants turned the haunting from insistent to wrathful. Never had I seen such things: eyes in the dark, hands reaching in desperation from under blankets. Several times, I was frightened to complete catatonia, curled and unable to move. Hoping to escape, I removed myself to the servants’ cottage, where the apparition found me on the second night. It pounded on the door, all the angrier for being ignored. I shrieked as it rapped on my window and scraped the pane with unseen claws. I thought of running many times. It was only the deep snow and my knowledge that I could not die that held me. In the end, I took a sledgehammer to the walls of the manor. Somewhere, I was sure, there was a door that needed to be opened. I found it in the nursery, boarded on two sides. Sweaty, panting, and covered in dust, I opened it without ceremony. It creaked on its hinges as it swung wide. Instantly, a lighter air settled over the roof. Within moments, a songbird alighted the branch of a tree near the window. My lord had mentioned in his letter that he hadn’t seen one on his estate in months.

I dropped the sledgehammer and wiped the sweat from my brow.

I had done it.

[image error]

Selection from the fifth and final mystery of my paranormal epic FEAST OF SHADOWS.

art by Kylie Parker

August 3, 2019

The Ripley Scroll

[image error]

There are approximately 23 copies of the Ripley Scroll in existence. The scrolls range in size, color, and detail but are all variations on a lost 15th century original. Although they are named after George Ripley, there is no evidence that Ripley designed the scrolls himself. They are called Ripley scrolls because some of them include poetry associated with the alchemist. The scrolls’ images are symbolic references to the philosopher’s stone. [Wikipedia]

Explore the scroll in full high definition on Google Arts.

[image error]

August 2, 2019

“No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” —Eleanor Roosevelt

August 1, 2019

(Music) Los Saicos!

Los Saicos formed in Peru in 1964 and lasted for a little less than two years. Having no real musical training, they played a pure garage sound that borrowed heavily from surf rock. Some claim the band originated punk, especially with their song “Demolición,” a decade before The Sex Pistols.

Initially the name of their band was “Los Sadicos.” However, perhaps to avoid being banned for suggesting sadism, they dropped the letter “d.” The band liked the new name not only for suggesting the popular battery-powered Seiko watch, but also the title of the famous Alfred Hitchcock thriller, Psycho.

Through a family connection, the unknown garage band played live on local radio before they had recorded a single song. The response was so strong, the radio station got them a spot on television, and almost overnight, Los Saicos were a hit.

“Come On” was their first single. Since the lead vocalist and bass player, César “Papi” Castrillón, couldn’t sing and play bass at the same time, he simply yelled into the microphone. Along with the guitarist Erwin Flores’s simple repeated power chords, the band created a raw, angry sound that resonated with Peru’s youth, exactly as punk would do in the 70s.

Los Saicos went on to release several more singles over the next 18 months, but by 1966, their popularity began to wane as fast as it had risen, and the band split. The four members went on to pursue more conventional careers. Flores and Castrillón eventually moved to the United States. Flores recorded two solo albums that were later shelved. He then moved to the Washington, DC area where he got a degree in Physics and worked for a number of years with NASA.

The band’s recordings survived, however, and developed an obscure following. Lux Interior, lead singer of the flashy 70s/80s punk band The Cramps, said Los Saicos were the greatest garage band of all time.

The three surviving members reunited in 2006. The music outlet Noisey released a short documentary film about the band in 2013.

July 31, 2019

True Story

When I was little, my parents took us to the circus. According to my mother, I was visibly enraptured by the knife thrower, so immediately after his performance, she asked me what I thought.

“It was okay,” I said, deflated. “But he kept missing her.”

[image error]

art by Sergio Martinez and Glenn Arthur

July 30, 2019

(Art) The Merry Occult of Tin Can Forest

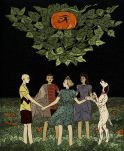

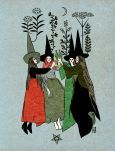

[image error]

Somewhere between a classic fairy tale and a modern pagan horror lies the work of Canadian duo Tin Can Forest, whose eerily whimsical illustrations seem torn from the pages of a lost tome, “The Children’s Guide to the Occult.”

July 29, 2019

(Fiction) In the Forest of Dusk

“Can I ask you something?” I said after a long silence.

“Only if I know the answer,” he replied, eyes closed. “I wouldn’t want to disappoint a woman of your stature.” A carpet of gray moss hung like a beard from his long face, and it wobbled when he spoke.

“That’s what I mean. You keep saying things like that. Like calling me ‘my lady.’”

He opened his eyes warily. “Yes?”

“Why?”

“Goodness me . . .” The question surprised him, and he shifted his prickly mass. Being a complete gnarl of growth, practically planted in place, the force caused several dry twigs to snap, like the crackle of old joints. “Well, aren’t you?”

“Aren’t I what?”

“A lady, of course.”

I opened my mouth to answer but stopped when I realized that answer was a lie. “I was,” I admitted. “Once. But that was a very long time ago. A very long time ago, indeed.”

“I miss the very long times ago,” he said, yawning. Even his tongue was a broad leaf. “You could really stretch out in them. The times today are so curt. Never bother to stick around, as if they’ve got some better place to be. Rude, if you ask me. Is that where you’re off to today, my lady? A very long time?”

“Oh, I hope not to be gone that long. I just planted my garden. If I’m not around to mind the strawberries, they’ll go to the birds.”

“Pesky things,” he said in a whisper. Then he looked around to see if anyone had heard. “But one must be polite, of course.”

“Of course,” I whispered back.

“Will you be taking the train today?”

“Train?” I looked across the dark undergrowth, hidden by the canopy overhead. It was identical in every direction. If the path I’d been following had ever continued, it had long since been swallowed by the forest. It was a very odd place to keep a train.

It seemed then that there wasn’t much reason to continue the ruse, and I dropped it. “I must be honest,” I said. “I seem to have lost some of my memories.”

“No!” He leaned back, aghast. “Truly?”

I nodded solemnly.

“That’s a terrible business. Terrible. Memories are like roots. They ought to stay where they’re planted.” He leaned closer like he wanted to tell me a secret. His face was as tall as my chest. “You know, when most people lose something, they wait until the last place to look before finding it, but I like to start there. Saves time, you see. And that’s important these days since there’s so much less of it than there used to be.”

“This is true. That’s a very good idea.”

“Thank you,” he said proudly. “But I can’t take credit for it. It was taught to me by a raven. Ravens are very clever, but this one was especially so.”

“It is very clever,” I said, “but I don’t think I have to worry about that. I’ve only ever kept my memories in one place.”

“Smart,” he said with a wink. “Very smart. Then you don’t have to worry where they’ve got off to. Have they escaped before?”

“Never.”

“Hmmm . . .” His leafy fingers stroked his mossy beard. “That’s good, but are you sure there’s nothing wrong with it?”

“With what?”

“The place you keep your memories. Perhaps it cracked.”

“Well, one can never be sure, but I’ve given it a good once-over, and it seems sound.”

“I see.” His face got dark. “Stolen then.”

“It certainly appears so.”

“You know,” he said thoughtfully, “I lost some memories once.”

“Did you find them?”

He opened his mouth to answer. Then he stopped and scowled at the heavy canopy over his head. “I don’t remember.”

I smiled. I couldn’t help it. “I suppose I shall have to keep looking.”

“Quite right. Best not to give up and all that. But you’d better hurry. The train is coming.”

I looked around again.

“Is . . .” He looked at me with one eye. “Is there a problem?”

“I’m sorry to be a bother,” I said, “but I seem to have lost the memory of where one catches the train.”

“Ah! On the platform, of course.”

“The platform.” I looked at the knee-high carpet of ferns. “And where is that?”

“Oh dear. I hope we haven’t lost that, too. I seem to recall it was around here somewhere.”

For several moments, we peered around the dim forest together.

“Ah!” His face lit suddenly. He lifted himself and pounded his heavy trunk on the ground so hard I nearly lost my footing. Several acorns fell and bounced on the ground. One hit my head.

“Get up, you lazy buggers!” he yelled. “The lady needs to know the way.”

Fireflies flickered among the ferns. They blinked like sleepy eyes as they drifted from their hiding places. They gathered into groups in the air, like dancing constellations, swirling as they coalesced. I watched in awe as the nearest formed a bright yellow ball inside an old iron street lamp, which, in the perpetual gloom, I had mistaken for the dead stump of a tree. The next group of fireflies lit the next lamp further down, and then the next, and the next, and so on in a straight line through the forest–remnant of some long-disappeared age.

“There,” he said with a nod. “That should keep the dark things at bay. But you must hurry.”

rough cut from the fifth and final course of my epic occult mystery, Feast of Shadows. Part One is available now.

[image error]

July 28, 2019

(Art & Faith) The Sorrow of Radha

The Gita Govinda, or “song” of Govinda, is a 12th century piece by the Indian poet Jayadeva which was later illustrated in a series of small paintings (circa 1775-1780) at Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, India.

“The Sorrow of Radha,” one image from the Tehri Garhwal Gita Govinda, depicts the milkmaid Radha in mourning after the departure of Krishna, avatar of Vishnu.

Vishnu is part of the Hindu “trinity:” Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Siva the destroyer. Unlike his Christian counterpart, Vishnu comes to earth in human form not just once but several times, although the avatar of Krishna is especially important.

Prior to this scene, Krishna dances in revelry with a group of gopis, or milkmaids, on the bank of the Yamuna river. Milkmaids, obviously, would not be born to a high caste, so there is a sense here of “Jesus among the poor.”

[image error] Gita Govinda, circa 1775\u20131780","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"Kronos Collections\/Metropolitan Museum of Art","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"\u2018Krishna and the Gopis on the Bank of the Yamuna River\u2019; miniature painting from the \u2018Tehri Garwhal\u2019 Gita Govinda, circa 1775\u20131780","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="‘Krishna and the Gopis on the Bank of the Yamuna River’; miniature painting from the ‘Tehri Garwhal’ Gita Govinda, circa 1775–1780" data-image-description="" data-medium-file="https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre..." data-large-file="https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre..." class=" wp-image-12504 alignright" src="https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre..." alt="‘Krishna and the Gopis on the Bank of the Yamuna River’; miniature painting from the ‘Tehri Garwhal’ Gita Govinda, circa 1775–1780" width="428" height="279" srcset="https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre... 428w, https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre... 854w, https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre... 150w, https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre... 300w, https://rickwayneauthor.files.wordpre... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 428px) 100vw, 428px" />

The dancing is ecstatic and symbolic of the rapture of the divine. There is also a distinctly sexual element since Hindus do not banish that part of human experience to Hell.

Krishna of course leaves. In fact, he is depicted as being “unfaithful” to the gopis, careless even, abandoning them without warning.

Here, the milkmaid Radha, who was especially devoted, has collapsed in shock and loss, a moment masterfully illuminated, not just by the isolation of the lone figure but by the peace of her surroundings. The river flows, the leaves rustle, the birds continue their forage, all completely oblivious to the plight of this poor woman, which for me heightens her sense of isolation. The artist has not put her a bleak and barren landscape, with withered grass and storm clouds on the horizon. The world does not share in Radha’s suffering, which is — like all true suffering — intensely personal.

[image error]This is a picture of a crisis of faith. This woman has not only experienced God’s love but His rapturous embrace. She has laughed as he spun her in a dance that seemed to transcend time. It’s not that she thought it would never end. It’s that, dancing, she had no sense of beginnings or endings.

But of course it does end, and seemingly without reason. Like Radha and Job, we the penitent ask, why has this happened to me? Why hast thou forsaken me, O Lord?

There is a town — symbolic of society — over the hill in the distance, but it is worlds away, nothing but a shadow. Radha is in the wilderness of human despair. And time flows by.

It would seem that’s the end. And yet, in the background, there is a tree that had been cut. Its branches have grown up and around the wound. Flowers now bloom out of season…

Goosebumps, man. This is great art.

July 26, 2019

(Art & History) The Mistick Krewe of Comus

[image error]

The Mistick Krewe of Comus, founded in 1856, is a New Orleans Carnival krewe. It is the oldest continuous organization of New Orleans Mardi Gras festivities.

Comus is the Greek god of revelry, merrymaking and festivity. He was the son and cup-bearer of the god Dionysus. The inspiration for the name came from John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus. Part of the inspiration for the parade was a Mobile, Alabama, Carnival mystic society, with annual parades, called the Cowbellion de Rakin Society (from 1830).

Prior to the advent of Comus, Carnival celebrations in New Orleans were mostly confined to the Roman Catholic Creole community, and parades were irregular and often very informally organized. Comus was organized by (largely Protestant) Anglo-Americans. Hence, there is some association with the ugly history of racism.

Membership in Comus was historically tied with membership in the private Pickwick Club, and for a time the two organizations were one. In 1884, the Club and the Krewe of Comus severed all official ties. In the 20th and early 21st centuries, their membership is not identical; but it is believed that there are members common to both groups.

Comus has jealously guarded the identities of its membership and the privacy of its activities (other than its parade), perhaps even more than the other Carnival organizations subscribing to the traditional code of secrecy.

Legend has it that admittance to the Mistick Krewe’s ball was so highly sought-after that uninvited persons have tried to beg, buy, or steal invitations to the ball. Even after the Mystic Krewe of Comus ball is over, its invitations are prized by collectors. They are both rare and uncommonly beautiful.

In 1991, the New Orleans City Council, led by Democrat Dorothy Mae Taylor, passed an ordinance that required social organizations, including Mardi Gras Krewes, to certify publicly that they did not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, gender, disability, or sexual orientation, in order to obtain parade permits and other public licensure. In effect the ordinance required these, and other private social groups, to abandon their traditional code of secrecy and identify their members for the city’s Human Relations Commission. The Comus organization (along with Momus and Proteus, other 19th-century Krewes) withdrew from parading, rather than identify its membership.

Two Federal courts later decided that the ordinance was an unconstitutional infringement on First Amendment rights of free association. Despite this, the Krewe of Comus has not returned to the streets to parade. (The Krewe of Proteus later returned.)

The Mistick Krewe of Comus still holds an annual ball on Mardi Gras night.

The 1873 Mystick Krewe of Comus “Missing Links” parade was an important event in Mardi Gras history, becoming one of the first major parades to use satire and political commentary. That year, there were no floats, but the members paraded in costumes made of papier-mache, based on the drawings in this collection. A Swedish lithographer, Charles Briton, made the designs.

Many of the images depict figures related to the Civil War and Reconstruction, such as Ulysses S. Grant, Benjamin Butler, and Louisiana Governor Henry Warmoth. Also depicted are notable figures such as Charles Darwin and Algernon Badger, head of the Metropolitan Police.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]