Rick Wayne's Blog, page 39

August 14, 2019

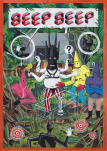

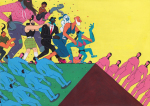

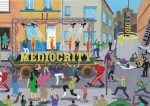

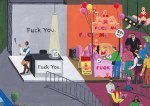

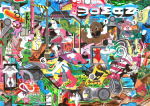

(Art) The Scathing Social Satire of Brecht Vandenbroucke

[image error]

Brecht Vandenbroucke is one of those artists, like Simon Stalenhag, where I would share every single painting they make. And yet, I realized today that I had featured neither of them on the blog. GASP

So today I fixed that.

August 13, 2019

(Fiction) The View From Space

[image error]

Here’s another one: Those who don’t study the past are doomed to repeat it. That might be true, but if so, none of you would know. You all don’t study the past. You study the one thing none of us in the past ever had, which is why you never learn any lessons from it. The past is a succession of presents. In each, we never know what’s going to happen. Those who inhabit the present, when it is the present, can’t help but feel privileged. Of all the people who ever lived, they possess the longest view, which is why, at every present, those in it believe their myths are not myths at all but the final realized truth. But by learning only what did happen, and not all of the things we thought would but didn’t, those in the present create a Frankenstein’s monster of falsehoods and live in terror of it, the terror of history. It’s as if, in memorizing the score of every contest in a sport, you pretend to know how to play.

In 1848, I was living in Bulgaria. That was the year people across Europe took to the streets. There were marches and demonstrations right across the continent, many of which broke into open revolution. It started in Sicily I’m told, but we didn’t know that at the time. It was the actions in France and Germany, more rumored than factual, that animated us. News didn’t spread by wire. It had to be carried by hand or hoof. That year, it came in from everywhere. Nothing like it had happened before—or since. Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, France, Germany, the Austrian Empire. The world seemed on the verge of change. How could it not, when so many had risen in protest?

But it failed. All of it failed. We couldn’t believe it. I still can’t, if I think about it. It doesn’t seem possible. I suspect those in the Arab world, living through the early 2010s, felt much the same.

In school, if you learn about 1848, you get a summary of what happened as if observed from space. You learn that tens of thousands of people died but not any of their names. Many more were beaten and exiled, I can assure you. Families were ripped apart. Destroyed. And for what? Reforms in the Low Countries? The eventual abolition of serfdom in the lands ruled by the Hapsburgs? I can tell you we imagined quite a bit more. We were beaten and shot and bayoneted and trampled for it. And when we woke the next morning—those of us who did—nothing had changed. The same men were in power. We envied those who had died, for they had died in noble cause. They lost their lives, but we lost our hope.

I remember there was a massacre in the town where I sought refuge. We called it a massacre. Some men started arguing outside a pub. A fight broke out. No one knows why. It could’ve been between a loyalist and a revolutionary but it could’ve just as easily been about a woman, or cards. But there was so much agitation then that when the soldiers came—There were no police. Only the army. And soldiers can only shoot or not shoot. So they shot, and four men were killed. A successful keeping of the peace in the eyes of the governor.

The next day, anger having simmered all night—stoked no doubt by the fires of rumor—a crowd gathered. They were led by a man we called Montaigne. That wasn’t his real name, but back then everything French seemed sophisticated. Progressive. So we called him Montaigne and he led us like a serpent through the streets so that our numbers could swell. And they did. By the time we reached the hospital, we were hundreds or more. When I say hospital, I don’t mean like today. It was a squat stone building that had once been a monastery. You didn’t go there to get well. You went there to die and not infect anyone else. The crowd called for the bodies of the dead men. There was no morgue. After whatever bureaucratic necessities had been completed, the dead were carried down the street—in the open on a cloth stretcher—and buried in the graveyard, usually in a plank coffin but sometimes without. But there weren’t any bodies at the hospital, we were told through a crack in the door, not from the massacre. They had already been given rights and interred.

It’s hard to describe what followed with any sense because it didn’t have any. There were shouts that it was a lie and the men’s bodies were being kept from us by order of the emperor’s men. Some people thought we should storm the hospital. Others didn’t even understand why we were there. Feeling his control slip, Montaigne stood on an upturned cart and addressed us, but there was no electronic augmentation, and it was very hard to hear, especially over the confused chatter, and soon the competing calls resumed.

If you believe the history books, these were calls for land reform, or the abolition or resurrection of certain legal rights. Standing on the ground, you wouldn’t have heard any of that. For most of the people in that crowd, destruction of the aristocracy was the furthest from their minds. If there was a theme, it was a return to the good old days, which they remembered fondly. In truth, those days weren’t very good either. Nor did they remember them. They remembered stories told by the elderly, who are perpetually dissatisfied by the way things have turned out and long for the simplicities of their youth, by which is meant all things familiar to them. There is no force on the human mind as potent as nostalgia—save sex and hunger.

I remember one old fellow was very put out that the crowd contained several foreigners, which is to say non-Bulgarians, myself included. For him, the tragedy was not that Bulgaria was ruled by an aristocracy. I don’t think he could’ve imagined life any other way. It was that so many of the governors and lords were Austrian—by culture at least, if not by birth—and that these foreigners could never be trusted to treat Bulgarians fairly. He wanted them out. He wanted Bulgaria for Bulgarians. I’m sure quite a few agreed with him, for I heard their chants competing with others: an end to conscription and dreams of no taxes—pleas for reform rather than revolution. It was Montaigne and his men who argued for the rest. I remember his lieutenants circling the crowd as he spoke, like sharks, calling out from different places to make it look like their ideas were more popular than they were. I remember them struggling to silence the others so that the great man could speak. From what I heard, his arguments were not entirely unpersuasive. The Hapsburgs, he pointed out, had ample opportunity for reform—decades, even—and they had persistently failed. How many chances were we to give them before we “took our destiny into our own hands?”

The wording, I’m sure, was intentional. It left everyone free to imagine a different “us.”

But our Montaigne was only a mediocre orator, and a crowd is a slippery thing. We could feel him struggle to hold on. No one knew what would happen. For their part, I’m sure the hospitalers were terrified. Nor could I blame them. In a panic, a body was brought out the front—an older man with a bald top and a stubble of a beard, dressed in simple, muddied clothes. A farmer or herdsman. From his perch atop the cart, Montaigne pointed suddenly to the door, a gesture that nearly caused the bearers to drop the body. Men from the crowd rushed forward and grasped the cloth stretcher and hoisted it in the air and the crowd cheered, momentarily elated at their success but unsure what they had achieved.

By chance, the dead man’s wife was among us. Whether she had come out of the hospital or joined us earlier, I couldn’t say, but she ran to the body of her husband and tried to pull him down. She was pleading with the men, who had broken into slogans and cheers, but I don’t think they heard her. In the jostle, they rebuffed her repeatedly as they carried the corpse of her husband into the street. They had now become the locus of the crowd, its center of gravity, and everyone swirled in orbit, desperate to touch or merely glimpse the holy martyr who had died nobly for the cause. Montaigne’s followers pushed through the tangle of bodies and practically forced their leader’s hand onto the stretcher. It wasn’t necessary that he support its weight, merely that he be seen touching it. Slowly, the competing calls narrowed to a few and then blended into one.

I spotted the old woman on the ground near the up-turned cart, whose perplexed owner stared at it with a hand to his forehead, wondering whether it was damaged and how he was going to right it on his own. The wife was scuffed but mostly unhurt. She just looked confused.

“What are they doing?” she asked me as I helped her to her feet. “My husband wasn’t a revolutionary. He didn’t want anything to do with those people. He dropped over in the field this morning castrating a sheep.”

“I don’t think they care,” I told her.

The crowd carried the body of the herdsman to the governor’s mansion, where in a series of short, rousing speeches, he was praised for his courage and sacrifice in the battle against tyranny. The timing was not an accident. The governor was then supping with some guests, dignitaries from another part of the empire, perhaps even the capital. It was because of their arrival, in fact, that the governor had given the army such unusual latitude to commit violence on behalf of peace. It was widely suspected that the purpose of the visit was to coordinate the empire’s response to the civil unrest then sweeping across the whole of Europe. But that was speculation. What we knew for sure was that the men and women inside that mansion were eating well. We knew it because we were the ones who had brought it. In the days preceding the dignitaries’ arrival, two sides of beef, several pigs, four casks of Tokay, and a mountain of fruits, breads, and cheese had been delivered to the mansion. The arrival of the crowd coincided with the consumption of the finer of those goods. We knew it, just as we knew we would be waiting for scraps to be thrown out the back at dawn the next day.

The governor’s response was swift, as if already contemplated. The second- and third-floor windows facing the square, all of which had been covered by heavy curtains, opened simultaneously, and long-barreled muskets jutted out. There was one brief moment of silence before they fired. Then there was only panic. Three were killed instantly. We knew because their still bodies never moved from in front of the gate. Several more, men and women both, had their shoulders shattered or heads cracked by the musket balls. As their friends dragged them away, bleeding, the muskets withdrew and the next set took their place. Another volley was loosed, to lesser effect as the crowd had already dispersed.

Among the victims was the dead herdsman, reborn a martyr and killed again. His hoisted body had been used as shield by Montaigne and his supporters, who huddled underneath as they scurried from the square. The corpse was later found in a stable, riddled with five holes, one each for Montaigne and his lieutenants, who survived and fled to another town, no doubt to repeat the pantomime again, this time armed with stories of their bravery in the face of massacre. I could never say they had caused the fight at the bar the day before, but it wouldn’t have surprised me.

No less than twelve people died, probably more, although there were only five corpses in the square. The rest fell to sepsis over the following days. The morning after, a handful of brave souls, rightly surmising that few of us would dare approach the governor’s mansion so soon, enjoyed the bounty of scraps from the feast, tossed as usual out the back. They ate like kings, they said, bragging. The townsfolk later decided this was a kind of treason, and the men were beaten to death in their beds. The women were exiled. From there came a quick descent into lawlessness, and the revolution bloomed in full.

I’ve not known anyone to suggest it, but I think the most lasting effect of that year was the birth of communism. Marx and Engels wouldn’t publish their infamous book for another two decades, but that’s only when the idea reached maturity. It was born in the failures of 1848, and everything that happened because of it—the long catastrophe that was the 20th century—happened in a sense because a handful of old men wouldn’t share their bread with those who needed it. But it is very hard to know any of that, let alone recognize it in our own present, in the view from space.

rough cut from the conclusion of FEAST OF SHADOWS. Part One is available now.

[image error]

cover image: Crows in a Frozen Forest by Matazō Kayama

August 12, 2019

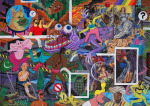

(Feature) Reading With a Tin Foil Hat

Those who compulsively hate on what’s popular never think that’s what they’re doing. Like the paranoiac who believes his tin foil hat is all that saves him from the government machine, these people legitimately confuse their tastes with objective fact and try to save the rest of us from ours.

I know. I used to be that guy. Enough decades separate us now that he almost seems a different person, but I know he would never have accepted that sometimes it’s enough to just leave it be, nor even that if you do so, you’re not “letting” people have their fun. Their fun is theirs and you have no claim to it.

Unfortunately, there are enough such people in the world that there also those who therefore assume if you speak against a popular movie or song, you’re just being difficult. I’m not sure that’s any better, honestly.

I’m finicky with novels. I just have to accept that.

I don’t want to be. I’d rather be carefree with my enjoyment, like I am with movies and like I used to be when I read voraciously, before I made the craft of fiction my job. I miss the exhilaration of reading, which feels every bit like the excitement of a first date.

But one’s faculties are not like iron. They don’t dull with use but actually get sharper. They only weaken with inactivity, like muscle.

There is no common definition of what makes a novel “good,” thankfully. If there were, it would be as simple as replicating that and writing novels would be prosaic, like cutting grass.

There are many prosaic novels, of course — orders of magnitude more than good ones. It’s where the word comes from.

But good and popular and prosaic and unpopular are not on the same axis. There’s nothing that says a popular novel can’t also be a prosaic one.

The difference is that, while there is no common definition of “good,” we can broadly sketch what makes a novel prosaic. If you don’t know, all the better. That means you can enjoy what’s popular and not have to worry about whether it’s any good.

But there is value in reading, even bad novels. A new study suggests reading actually changes the brain.

“The neural changes that we found associated with physical sensation and movement systems suggest that reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist,” says neuroscientist Gregory Berns, lead author of the study and the director of Emory University’s Center for Neuropolicy. “We already knew that good stories can put you in someone else’s shoes in a figurative sense. Now we’re seeing that something may also be happening biologically.”

The neural changes were not just immediate reactions, he says, since they persisted the morning after the readings, and for the five days after the participants completed the novel.

“It remains an open question how long these neural changes might last, but the fact that we’re detecting them over a few days for a randomly assigned novel suggests that your favorite novels could certainly have a bigger and longer-lasting effect on the biology of your brain.”

“Stories shape our lives and in some cases help define a person,” says Berns.

It’s a two-edged sword, of course. On the one hand, the brain hungers for narrative. So it is, within hours of Jeffrey Epstein’s death, millions of people on Twitter and around the world were already sharing coherent narratives for why it happened and who was to blame, despite that not a single human on the planet yet had even half the facts.

So, too, people take to YouTube the moment a trailer comes out to dissect all 200 seconds of it and unpack from that the whole of the two-hour movie that won’t be released for five months.

It’s as if the brain is a kind of anti-Heisenberg machine. It cannot exist in a state of uncertainty. It MUST decide, and having decided, will stick to it. The particle will never again be a wave, and vice versa.

Indeed, several days after Saturday’s events, we’re still told there are only two possible suspects in the whole world, which is of course a way of orienting this episode — indeed, of making it an episode — within the larger drama of this season of American Politics, which pits a single set of good guys (with a leader) against a single set of bad guys (with a leader), with the entire country at stake!

And people make fun of superhero movies…

I alternate between feeling sorry for those folks and feeling angry at them. They are the reason we can’t have nice things.

Of course, at the other extreme, that same narrative-seeking plasticity can, with time, training, and effort, liberate us from itself, the same way a puzzle box can be locked and unlocked with no key.

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realize the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realize it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others. Reality, even seen through the eyes of many, is not enough. I will see what others have invented. Even the eyes of all humanity are not enough. I regret that the brutes cannot write books. Very gladly would I learn what face things present to a mouse or a bee; more gladly still would I perceive the olfactory world charged with all the information and emotion it carries for a dog.

Literary experience heals the wound, without undermining the privilege, of individuality. There are mass emotions which heal the wound; but they destroy the privilege. In them our separate selves are pooled and we sink back into sub-individuality. But in reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like a night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.

–C.S. Lewis

Incidentally, this is why I can’t truck with these folks who say that if a book is racist or sexist or whatever, we should discourage students from reading it. That suggests, for one, that the list of Party-approved authors are noble–and so, by association, the Party and all its members.

Authors are not noble. We’re not that kind of species. But even if by some miracle yours are, I don’t read Nabokov–or better yet Bukowski, because he’s noble. He’s not. He’s despicable. Grimy. He oozes resentment and stale tobacco.

I read Bukowski because such people exist, and because he does it so well he takes me outside myself. To proscribe the mean, the foreign, the nasty is to leach literature of its singular value and reduce it to the mechanical act of inculcation, which I suspect is the point — not to empower the student to enervate her own destiny, but to take out something we don’t like and put something else in its place.

I don’t want to go off on too many tangents, but one final and exciting implication of the study is that emergent properties, like consciousness, can alter the world in a top-down fashion.

This is opposed the pure reductive model, which says that all complex phenomena are built up from smaller and smaller parts.

That’s not to say complex phenomena aren’t mediated by some kind of substrate. Brains cause minds. They don’t simply hold them. It’s not at all clear yet that you can have a mind without a brain, or similar structure, to mediate it.

In fact, I doubt it. A mind is not a “thing” in the classical sense, which is why there’s so much shoddy thinking about consciousness: it requires a new category of existence. I doubt a mind can be ported, for example, and remain the same mind, despite the dreams of science fiction writers.

But that takes us too far afield. The point is simply that emergent phenomena like minds can alter the physical structure of the world in ways that couldn’t happen if they were nothing but a collection of bits, and that the humble act of reading participates in that.

[image error]art by Sofia Bonati

Reading With a Tin Foil Hat

Those who compulsively hate on what’s popular never think that’s what they’re doing. Like the paranoiac who believes his tin foil hat is all that saves him from the government machine, these people legitimately confuse their tastes with objective fact and try to save the rest of us from ours.

I know. I used to be that guy. Enough decades separate us now that he almost seems a different person, but I know he would never have accepted that sometimes it’s enough to just leave it be, nor even that if you do so, you’re not “letting” people have their fun. Their fun is theirs and you have no claim to it.

Unfortunately, there are enough such people in the world that there also those who therefore assume if you speak against a popular movie or song, you’re just being difficult. I’m not sure that’s any better, honestly.

I’m finicky with novels. I just have to accept that.

I don’t want to be. I’d rather be carefree with my enjoyment, like I am with movies and like I used to be when I read voraciously, before I made the craft of fiction my job. I miss the exhilaration of reading, which feels every bit like the excitement of a first date.

But one’s faculties are not like iron. They don’t dull with use but actually get sharper. They only weaken with inactivity, like muscle.

There is no common definition of what makes a novel “good,” thankfully. If there were, it would be as simple as replicating that and writing novels would be prosaic, like cutting grass.

There are many prosaic novels, of course — orders of magnitude more than good ones. It’s where the word comes from.

But good and popular and prosaic and unpopular are not on the same axis. There’s nothing that says a popular novel can’t also be a prosaic one.

The difference is that, while there is no common definition of “good,” we can broadly sketch what makes a novel prosaic. If you don’t know, all the better. That means you can enjoy what’s popular and not have to worry about whether it’s any good.

But there is value in reading, even bad novels. A new study suggests reading actually changes the brain.

“The neural changes that we found associated with physical sensation and movement systems suggest that reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist,” says neuroscientist Gregory Berns, lead author of the study and the director of Emory University’s Center for Neuropolicy. “We already knew that good stories can put you in someone else’s shoes in a figurative sense. Now we’re seeing that something may also be happening biologically.”

The neural changes were not just immediate reactions, he says, since they persisted the morning after the readings, and for the five days after the participants completed the novel.

“It remains an open question how long these neural changes might last, but the fact that we’re detecting them over a few days for a randomly assigned novel suggests that your favorite novels could certainly have a bigger and longer-lasting effect on the biology of your brain.”

“Stories shape our lives and in some cases help define a person,” says Berns.

It’s a two-edged sword, of course. On the one hand, the brain hungers for narrative. So it is, within hours of Jeffrey Epstein’s death, millions of people on Twitter and around the world were already sharing coherent narratives for why it happened and who was to blame, despite that not a single human on the planet yet had even half the facts.

So, too, people take to YouTube the moment a trailer comes out to dissect all 200 seconds of it and unpack from that the whole of the two-hour movie that won’t be released for five months.

It’s as if the brain is a kind of anti-Heisenberg machine. It cannot exist in a state of uncertainty. It MUST decide, and having decided, will stick to it. The particle will never again be a wave, and vice versa.

Indeed, several days after Saturday’s events, we’re still told there are only two possible suspects in the whole world, which is of course a way of orienting this episode — indeed, of making it an episode — within the larger drama of this season of American Politics, which pits a single set of good guys (with a leader) against a single set of bad guys (with a leader), with the entire country at stake!

And people make fun of superhero movies…

I alternate between feeling sorry for those folks and feeling angry at them. They are the reason we can’t have nice things.

Of course, at the other extreme, that same narrative-seeking plasticity can, with time, training, and effort, liberate us from itself, the same way a puzzle box can be locked and unlocked with no key.

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realize the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realize it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others. Reality, even seen through the eyes of many, is not enough. I will see what others have invented. Even the eyes of all humanity are not enough. I regret that the brutes cannot write books. Very gladly would I learn what face things present to a mouse or a bee; more gladly still would I perceive the olfactory world charged with all the information and emotion it carries for a dog.

Literary experience heals the wound, without undermining the privilege, of individuality. There are mass emotions which heal the wound; but they destroy the privilege. In them our separate selves are pooled and we sink back into sub-individuality. But in reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like a night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.

–C.S. Lewis

Incidentally, this is why I can’t truck with these folks who say that if a book is racist or sexist or whatever, we should discourage students from reading it. That suggests, for one, that the list of Party-approved authors are noble–and so, by association, the Party and all its members.

Authors are not noble. We’re not that kind of species. But even if by some miracle yours are, I don’t read Nabokov–or better yet Bukowski, because he’s noble. He’s not. He’s despicable. Grimy. He oozes resentment and stale tobacco.

I read Bukowski because such people exist, and because he does it so well he takes me outside myself. To proscribe the mean, the foreign, the nasty is to leach literature of its singular value and reduce it to the mechanical act of inculcation, which I suspect is the point — not to empower the student to enervate her own destiny, but to take out something we don’t like and put something else in its place.

I don’t want to go off on too many tangents, but one final and exciting implication of the study is that emergent properties, like consciousness, can alter the world in a top-down fashion.

This is opposed the pure reductive model, which says that all complex phenomena are built up from smaller and smaller parts.

That’s not to say complex phenomena aren’t mediated by some kind of substrate. Brains cause minds. They don’t simply hold them. It’s not at all clear yet that you can have a mind without a brain, or similar structure, to mediate it.

In fact, I doubt it. A mind is not a “thing” in the classical sense, which is why there’s so much shoddy thinking about consciousness: it requires a new category of existence. I doubt a mind can be ported, for example, and remain the same mind, despite the dreams of science fiction writers.

But that takes us too far afield. The point is simply that emergent phenomena like minds can alter the physical structure of the world in ways that couldn’t happen if they were nothing but a collection of bits, and that the humble act of reading participates in that.

[image error]art by Sofia Bonati

August 11, 2019

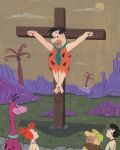

(Art) The Night Whimsies of Christian Schloe

[image error]

Although they look like paintings, the works of prolific Austrian artist Christian Schloe are actually composed in Photoshop. Through the themes of night and flight, where everything is aloft on wings or trees or water, the artist invokes the floating sensation of a dream.

Prints of his work are available on Society6.

August 10, 2019

Fall of the Rebel Angels (1554) by Frans Floris (Flemish...

[image error]

Fall of the Rebel Angels (1554) by Frans Floris (Flemish, 1519-1570)

August 9, 2019

(Art) Meanwhile, in Russia…

The Atlantic’s Photos of the Week are a perpetually shocking reminder to me that it’s a great big world after all, and not just a human one, and that the nightly dramas being played on our televisions, real or imagined, are only one tent of the circus.

Consider following. They come out every Friday.

[image error]ANTALYA, TURKEY – AUGUST 6: Tourists take photos at antique theatre of Aspendos, built by the Romans in 160-180 A.D, in Serik district of Antalya, Turkey on August 6, 2019. Aspendos, which is among the examples of the best designed Roman theaters, is one of the best-preserved ancient amphitheater and is still used for concerts and festivals. (Photo by Orhan Cicek/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

[image error]https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/201...

Meanwhile, in Russia…

The Atlantic’s Photos of the Week are a perpetually shocking reminder to me that it’s a great big world after all, and not just a human one, and that the nightly dramas being played on our televisions, real or imagined, are only one tent of the circus.

Consider following. They come out every Friday.

[image error]ANTALYA, TURKEY – AUGUST 6: Tourists take photos at antique theatre of Aspendos, built by the Romans in 160-180 A.D, in Serik district of Antalya, Turkey on August 6, 2019. Aspendos, which is among the examples of the best designed Roman theaters, is one of the best-preserved ancient amphitheater and is still used for concerts and festivals. (Photo by Orhan Cicek/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

[image error]https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/201...

August 8, 2019

(Art) The Cosmic Fantasy of Piotr Jabłoński

[image error]

Piotr Jabłoński is a Polish artist and illustrator who has produced a volume of video game and book cover art, notably for the Dishonored series and Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melnibone. His moody, ethereal atmospheres, where the world seems trapped in a haze of perpetual dusk, create a sense of deep and hidden otherworldliness and so lend themselves well to stories like Elric or the work of H.P. Lovecraft.

August 5, 2019

(Feature) No Excuses

We are never as creative as when making excuses for why we can’t be.

Akira Kurosawa, for those who don’t know, wasn’t just one of the greatest directors in Japan. He was one of the greatest directors of the 20th century and a founding voice in the cinematic arts.

The joke goes, he was every Western director’s favorite artist to steal from. His 1958 black-and-white film The Hidden Fortress was direct inspiration for George Lucas’s Star Wars, both the original film and The Phantom Menace — and that is putting it charitably.

It went both ways, of course. There’s a story about Kurosawa, certainly apocryphal but I’m sure with a grain, that tells of his assistants running to him one day in a fit.

“What’s wrong?” he asks.

“Sensei,” they say, “The Italian, Sergio Leone, has made a movie called A Fistful of Dollars, and it is Yojimbo!”

“Yes,” the master says coolly. “I heard it was like Yojimbo.”

“It is not ‘like’ Yojimbo, sensei,” the assistants object. “It IS Yojimbo! You must do something.”

“No, no,” he waves them off. “We will do nothing.”

“But…” the assistants stammer. “But why, sensei?”

“Because,” the master says, returning to his work. “Yojimbo is Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest.”

(In fact, a case was brought, although it seems to have been settled out of court.)

In Japan, once you reach master status, you’re expected to speak tersely and with zen-like wisdom about your craft. Kurosawa had a lot to say about art and creativity, but he seemed almost offended, certainly annoyed, by excuses.

Take the following quote, one of my favorites, given in an interview near the end of his life.

“The thing I stress the most to the aspiring directors who often come knocking at my door is this: ‘It cost a great deal of money to make a film these days, and it’s hard to become a director. You must learn and experience various things to become a director, and it’s not so easily accomplished. But if you genuinely want to make films, then write screenplays.

All you need to write a script is paper and pencil. It’s only through writing scripts that you learn specifics about the structure of film and what cinema is.’ That’s what I tell them, but they still won’t write. They find writing too hard. And it is. Writing scripts is a hard job.

The tedious task of writing has to become second nature to you. If you sit down and write quietly the whole day you’ll have written at least two or three pages, even if it’s a struggle. And if you keep at it, you’ll eventually have a couple of hundred pages. I think young people today don’t know the trick of it. They start and want to get to the end right away.

When you go mountain climbing, the first thing you’re told is not to look at the peak but to keep your eyes on the ground as you climb. You just climb patiently one step at a time. If you keep looking at the top, you’ll get frustrated. I think writing is similar. You need to get used to the task of writing. You must make an effort to learn to regard it not as something painful but as routine. But most people tend to give up halfway.

I tell my assistant directors that if they give up once, then that’ll be it, because that becomes a habit, and they’ll give up as soon as it gets hard. I tell them to write all the way to the end no matter what, until they get to some sort of end. I say, ‘Don’t ever quit, even if it gets hard midway.’ But when the going gets tough, they just give up.”

I spent the last couple years finishing FEAST OF SHADOWS for this exact reason. It’s an odd book. As I noted in a recent interview, it’s not like my others, and I will probably lose readers. But I needed to finish it. Not because it was easy. Because it was hard.

It sounds so lofty and artistic. “I have to finish it.” But it’s not. It’s the opposite of that. I can think of nothing more mundane than sitting down and finishing your work.

There’s a kind of paradox, as the master notes. Everybody wants to rush to the end, but to write quickly, you need to write slowly. That is, making a living at the craft — forget completely about fame, which is not a reason to do anything — making a living requires that you produce swiftly at high quality, but you can’t do that until you’ve reached a certain proficiency, and you can’t reach proficiency except by practice, practice, and more practice.

That doesn’t mean writing words. Poets make words. Novelists make novels. Practice means making novels, complete novels — or complete films, as the case may be, versus taking pictures or making snippets.

Not that you’re a dilettante if you’ve yet to finish a creative project. But you might be.

No one writes solely for money or solely for art. I’m not sure anyone who’s tried ever produced anything worth reading. (A good story, one that resonates, is one written to be read rather than to exist as an object unto itself.)

No one is born a novelist or film-maker either. If you expect to be any good at it, you have to suffer the hard bits. That’s where you learn.

The good news, Kurosawa tells us, is that if you’ve never finished a project, or have yet to try, it’s not too late.

In 1988, famed director Ingmar Bergman released his memoirs, called “The Magic Lantern,” wherein he admitted “I probably do mourn the fact that I no longer make films.”

Reading this, Kurosawa sent him a short letter:

Dear Mr. Bergman,

Please let me congratulate you upon your seventieth birthday.

Your work deeply touches my heart every time I see it and I have learned a lot from your works and have been encouraged by them. I would like you to stay in good health to create more wonderful movies for us.

In Japan, there was a great artist called Tessai Tomioka who lived in the Meiji Era (the late 19th century). This artist painted many excellent pictures while he was still young, and when he reached the age of eighty, he suddenly started painting pictures which were much superior to the previous ones, as if he were in magnificent bloom. Every time I see his paintings, I fully realize that a human is not really capable of creating really good works until he reaches eighty.

A human is born a baby, becomes a boy, goes through youth, the prime of life and finally returns to being a baby before he closes his life. This is, in my opinion, the most ideal way of life.

I believe you would agree that a human becomes capable of producing pure works, without any restrictions, in the days of his second babyhood.

I am now seventy-seven (77) years old and am convinced that my real work is just beginning.

Let us hold out together for the sake of movies.

With the warmest regards,

Akira Kurosawa

Start. Finish. No excuses.

[image error]

Feast of Shadows is available here.