C.J. Stone's Blog, page 4

June 7, 2021

Landscape and Possession

*

“I have seen the ghost of a different time out there in that landscape. I have seen the ghost of another kind of mind”

CJ Stone

"As I was walking a ribbon of highwayI saw above me an endless skywayI saw below me a golden valleyThis land was made for you and meAs I was walkin' - I saw a sign thereAnd that sign said - Private PropertyBut on the other side .... it didn't say nothin!Now that side was made for you and me!"

"As I was walking a ribbon of highwayI saw above me an endless skywayI saw below me a golden valleyThis land was made for you and meAs I was walkin' - I saw a sign thereAnd that sign said - Private PropertyBut on the other side .... it didn't say nothin!Now that side was made for you and me!"— This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie

People ask me what attracted me to this country. It had something to do with the landscape.

There are four photographs that show the process. Two are of the landscape itself. There’s a valley surrounded by wooded hills, with a scattering of cottages in small, fenced enclosures, with a few of those characteristic Transylvanian haystacks dotted about: the ones that look like witch’s bonnets. Drifting wood smoke. Small barns. A hint of shepherds with their flocks. It’s very picturesque, in a picture-postcard sort of way. It looks like a painting. But the thing you notice, beyond the small-scale farmsteads with their enclosures, there are no fences: just woods and hills reaching to the horizon. I think this is what touched me so deeply when I looked out upon it and which I found so difficult to describe: this landscape isn’t owned. It is the landscape that encloses the human, not the other way round. The picture is one of human beings being occupied in a landscape, not one of human occupation. It is a landscape without possession. The land doesn’t appear to be owned by anyone. Perhaps it is the landscape that does the owning: perhaps it owns all the creatures, human and otherwise, who dwell within it. After all, the landscape is bigger than the rest of us, and it has been around much, much longer.

Does the land belong to us, or do we belong to the land?

The next two photographs are of me and a friend in the place where the first two photographs were taken from, maybe two or three minutes later.

My friend is looking cool and relaxed, as usual, with his shades and his skinhead cut, in a tee-shirt that shows his tattoos. In the first I’m standing next to him in my leather jacket, looking slightly hunched; in the next I’m embracing him and he is joking with me. In both I have this look on my face. I’m smiling, but about to cry. It’s a look of deep intensity, as if I’ve just seen a ghost.

In a way, that is exactly what I have seen. I have seen the ghost of a different time out there in that landscape. I have seen the ghost of another kind of mind.

That is what I mean by possession.

When a ghost enters a man we say he is possessed.

But what if he is already possessed and he no longer knows it?

What if the mind that he carries around in his head isn’t his real mind at all?

What if it isn’t just one man, but all of humanity that is possessed? Possessed by the demon of possession, in fact, by the mistaken belief that anyone can ever own anything. What if there are people, even now, casting dark spells over you, in order to possess your mind. What if the god you worship, all unknowingly, is in someone else’s power?

Can a man be possessed by his own possessions? Can the objects he owns own a man? The ghosts aren’t things but thoughts. They are in the relationship between a human and the world he inhabits. Does he see the world, or does he only see what can be bought and sold? How does he make the world his own? By sealing it with money, or by animating it with his thoughts? By planting it with keep out signs, or by planting it with seeds? With the dead hand of legal obligation, or with the embrace of physical graft? By signing contracts or by building a home?

We have “ownership”, we have “possession”, we have “occupation” and we have “belonging”. All of them are words with more than one meaning.

So “occupation”. It is occupation that occupies a man. We have our jobs, our occupations. We are occupied. But then, when one country invades another we call that “occupation” too. Occupied France in the Second World War. The Occupied Territories in what were once Palestine. Occupied Iraq. Occupied Afghanistan. The question then is, when we say that the landscape is occupied by humans what do we mean? Occupied as in an occupying army – a band of foreign invaders in the landscape imposing an alien culture upon it, degrading it, destroying it, murdering its inhabitants, exploiting it, marching all over it with storm-trooper boots of oppression? Or as human beings merely working in the landscape, working with the land, being occupied within it?

And when we say we “own” something, how do we own it? You can own a thought. You can own a knowledge. You can “own up” to things. None of these involve a legal relationship. Ownership here is just the acceptance of responsibility. It doesn’t imply possession at all.

It is the same with “belonging”. We can belong to a club, or to a tribe, or to a culture. We don’t say that the club “owns” us. Belonging, in this sense, is a relationship with something, the way we say two people belong to each other, the way a child belongs to a mother, or a man belongs to a women. It is a relationship over time: a be-longing, a being-over-time. A longing. A longing to belong.

All cultures have a sense of ownership in these terms, as relationship, as knowledge, as commitment, as work. But most cultures until very recent times did not have a sense of possession in the way we now have it: of a legalised and exclusive ownership, of an ownership that implies that what belongs to one cannot therefore belong to another. Common ownership was once the norm. This is what has changed. And the joke here, of course, is that when you look at who owns what in these legal terms, most people in the world own very little, or nothing at all, and a very few people own almost everything.

This form of possession is invisible, like a ghost. It is exactly like possession in that other, occult sense. A man does not need to have done anything to have this form of ownership. He does not need to have built a farm, or raised crops, or raised a family. He does not need to have worked the land or to have maintained it, to have tilled the soil, to have built fences, to have planted seeds, to have reaped the harvest. He does not need to have hunted on it. He does not need to know where the wild creatures go. He does not even need to have visited it. He need not know where it is. All he needs is a bit of paper that says he owns it, and when he wants to dispossess the man who is actually living on it, and who has raised crops and a family and built a home, he can. The joke is that we have all been sold into this form of possession, and yet all it has achieved is to have dispossessed us all.

Possessed and dispossessed, all at the same time.

And who, now, truly “owns” the land in which he lives? Who, now, owns it in the form of knowledge, in the form of belonging, in the form of being occupied within it, of being occupied by it? Who, now, can hear the land talking to us? Who can hear its secret words of wisdom, in the wind, in the trees? Who, now, knows the rituals of the landscape, it’s cycles and its seasons, and the potent alchemy that plants perform to turn dirt and air into food? Who knows its secrets? Who knows its charm? And who, now, knows how to charm it and be charmed by it? Who knows its magic?

The hint out there in that distant landscape is of a time when a legalised form of possession was the exception, not the rule, when lands were held in common, and when humans took their abode in the landscape as passing strangers in the sacred dimension of time; when we shared the land with the other creatures of the landscape, with the wolves and with the bear, with the snake and with the eagle, and when we allowed the landscape to enter us and possess us with it’s abiding, ancient presence, and never tried to claim but temporary ownership of what can never, in the end, belong to anyone.

Let’s face it: death takes all possession away, but the landscape will remain forever.

How You Can HelpMake sure you share and like these articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going.Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/ https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60bf3be88a721', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60bf3be88a721', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

June 6, 2021

Antinomian Prophet

*

*

I’ve just read John Higgs’ latest book, William Blake vs The World, for the third time in a row. It’s not often I’m so impressed by a book that I get to the end and promptly start all over again. It’s only happened with a few books in my life. Another was Witness Against the Beast by EP Thompson, also about William Blake. It’s worth comparing the two books.

Thompson’s book is an exposition of an idea first suggested by AL Morton in his 1958 work The Everlasting Gospel, that Blake was an antinomian: that he was from a tradition dating back to the English Civil War, characterized by such lost and forgotten groups as the Ranters and the Diggers. “Antinomian” means “against the law.” As a historian, Thompson identifies one particular group whose ideas bear some resemblance to Blake’s, the Muggletonians, and suggests some direct connection between them. Was Blake a Muggletonian, he asks?

Recent scholarship has rejected that idea, but it seems to me that this is a profound misreading of Thompson’s work. While the last quarter of Witness Against the Beast is an exploration of this strange, forgotten sect, which somehow managed to survive into the 20th century, the bulk of his book is about the parallels between the antinomian tradition—the English Dissenting, or English Radical Tradition, as it’s known—and the writings of William Blake; and it’s clear from the context and the language that there are such links.

Was Blake a Muggletonian? No. But the echoes of Civil War antinomian and dissenting thought were still extant in London during Blake’s lifetime, and it’s hard not to imagine that he wasn’t influenced by them. If we were to ask how those ideas survived for such a long period, from the 1640s to the 1750s, let’s remember that two of those strands are still in existence in the present, in the form of the Baptist Church, and the Quakers, both of whom were considered extremely radical in their day.

When I first read Thompson’s book, I identified strongly with the tradition he was describing, which began a process of exploring some of those ideas. It explained why Blake continues to have such resonance, and why, from the first time I read him, I became obsessed. I’m not the only one. The point about Thompson’s book is that it was written, not by a Blake scholar or a biographer, but a historian, and it takes a completely different approach to most previous books on the subject.

The same is true of Higgs’ book. Higgs is not a Blake scholar. He’s not a historian and his book isn’t literary criticism. It’s not biography, although it does contain elements of all these things. Rather, it’s an explanation, an exploration, a way of approaching Blake that makes him relevant to our own lives. Higgs’ book is as much about us as it is about Blake. If the book does contain biographical elements (how could it not?) it’s also the biography of one of Blake’s central characters, Urizen. You’d recognize him. He’s the subject of one of Blake’s most famous prints. Picture him. He’s naked in a circle of light, leaning down with a pair of compasses to measure the Earth below. His white hair and beard are blown sideways and he’s surrounded by dark, ominous clouds. He’s called The Ancient of Days.

This is Urizen, an image that originally appeared in one of Blake’s prophetic books, Europe a Prophesy, and which he recreated at intervals throughout his life. You’d probably imagine him as a representative of God. As Blake said in his later book Milton, “Urizen is Satan.” This would probably have come as a great surprise to the custodians of St Paul’s Cathedral, on whose dome an image of Urizen was projected during the Blake exhibition at the Tate in 2019. I wonder if they would’ve allowed it had they realized who Blake himself identified the image with?

There are different interpretations of what the name “Urizen” means. Probably a combination of “your horizon” and “your reason.” Urizen is the representative of rational thought, and is echoed again in another famous Blake image, of Newton sitting on an antediluvian rock, leaning down and measuring out geometrical shapes onto a roll of paper. Newton is absorbed in his task; so much so that he’s unable to appreciate or even acknowledge the astonishing beauty of the world in which his focused study takes place.

Here is Higgs’ description of the character: “Urizen is the personification of reason. He is the intellect that creates law, he is controlling and associated with language, and it is he who constructs the human-scale world of rationality and logic in which contrary positions cannot both be physically true. Urizen is the conscious observer that forces Schrodinger’s cat to become either alive or dead.”

The reference to Schrodinger’s cat tells us where Higgs is going to take his story. Higgs is first and foremost a student of Robert Anton Wilson. He takes a similar approach. His book ranges over a wide variety of subjects, taking in quantum mechanics, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, culture and theology in a way that links these disparate elements together into a coherent narrative.

Urizen is central to Higgs’ book, as he is to Blake’s work, because Urizen is central to us. He is us: us as we appear to ourselves. Us as the story of our lives which we construct and reconstruct on a daily basis. Us as the default mode network, the top-down, rational model of the Universe we carry around in our heads, which allows us to navigate around our world efficiently but which, as Higgs describes it, “cauterises chaotic imagination.”

Urizen is the ego, the creator God who made the world in his own image. Blake’s entire output is about rebalancing the world, recreating it in the imagination, liberating it from the limitations of one-dimensional thought and returning us to the visionary world from which we came, and which Blake himself still inhabits.

It’s this that makes Higgs’ book so useful. He wrests Blake out of the hands of the academics and returns him to the people, where he belongs. He shows us how relevant Blake’s vision is in this time of crisis and confusion, and how crucial it is for all of us to try to see the world the way Blake saw it, not as “the single vision” of “Newton’s sleep,” but in all its multifaceted, dynamic, imaginative, psychedelic, multidimensional, visionary glory. Reading Higgs’ book is one step towards experiencing that world again.

Originally appeared here.

‘A glittering stream of revelatory light . . . Fascinating’ THE TIMES

‘Rich, complex and original’ TOM HOLLAND

‘One of the best books on Blake I have ever read’ DAVID KEENAN

‘Absolutely wonderful!’ TERRY GILLIAM

‘An alchemical dream of a book’ SALENA GODDEN

‘Tells us a great deal about all human imagination’ ROBIN INCE

***

Poet, artist, visionary and author of the unofficial English national anthem ‘Jerusalem’, William Blake is an archetypal misunderstood genius. His life passed without recognition and he worked without reward, mocked, dismissed and misinterpreted. Yet from his ignoble end in a pauper’s grave, Blake now occupies a unique position as an artist who unites and attracts people from all corners of society, and a rare inclusive symbol of English identity.

Blake famously experienced visions, and it is these that shaped his attitude to politics, sex, religion, society and art. Thanks to the work of neuroscientists and psychologists, we are now in a better position to understand what was happening inside that remarkable mind, and gain a deeper appreciation of his brilliance. His timeless work, we will find, has never been more relevant.

In William Blake vs the World we return to a world of riots, revolutions and radicals, discuss movements from the Levellers of the sixteenth century to the psychedelic counterculture of the 1960s, and explore the latest discoveries in neurobiology, quantum physics and comparative religion. Taking the reader on wild detours into unfamiliar territory, John Higgs places the bewildering eccentricities of a most singular artist into context. And although the journey begins with us trying to understand him, we will ultimately discover that it is Blake who helps us to understand ourselves.

Available here: https://www.weidenfeldandnicolson.co.uk/titles/john-higgs/william-blake-vs-the-world/9781474614375/

How You Can HelpMake sure you share and like these articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going.Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/ https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60bca6922c635', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60bca6922c635', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

May 22, 2021

Locked Out: In Memory of Nick Hayes

By CJ StoneAll life is sacred.

I was sorry to hear of the death of Nick Hayes in April.

He wrote a couple of pieces for Whitstable Views and I was hoping to work more with him in the future.

I didn’t really know him. I met him once, at the gate of the house he was living in in Tankerton, when I was dropping off a book for him.

It was a synchronous moment. I’d just got off the bus and was on my way to my sister’s to walk her dog. I’d arranged to drop the book through his door on the way, as Nick had said he wasn’t going to be in.

And then, there he was! We reached the gate of his house at exactly the same time, coming from opposite directions. We both recognised each other immediately. There was a fierce light in his eyes.

The book was

View original post 1,533 more words

May 8, 2021

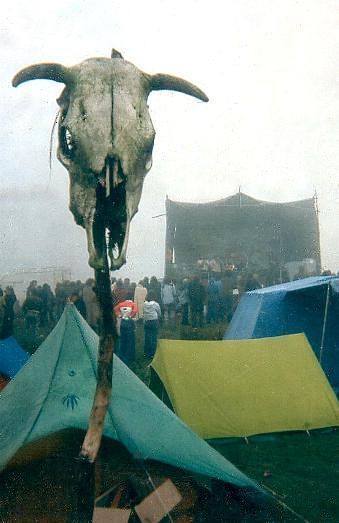

Country Crass

Photo: Barbara Fg.

Do they owe us a living? Of course they do.I belong to a few groups on Facebook. One of my favorites is called Punk New Age Travellers. It was there that I first heard the track “Do They Owe Us A Living” by Croy and the Boys. Astute readers will recognize the title as a Crass song, from their first album The Feeding of the 5000. The Crass version is an aural and verbal assault, lyrics delivered with machine gun rapidity over a screeching, violent guitar-and-drum track. It reeks of anger and alienation. It’s almost incomprehensible, and without the written lyrics to guide you, you’d be hard put to make any sense of it.

The Croy and the Boys version, on the other hand, is classic Country and Western, with a little Tex-Mex thrown in, complete with pedal steel guitar and accordion, a crooning voice and a lyrical bass. It’s laid back and approachable, danceable, and will slink its way into your head like a silk sheet on a Queen-size bed.

Which is what makes the anger in the lyrics even more incendiary:

Do they owe us a living? Of course they do.Owe us a living? Course they do, course they do.Owe us a living? Of course they fucking do.Read more here: https://www.splicetoday.com/pop-culture/country-crass

The EP is available here.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60965961434a7', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60965961434a7', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

May 7, 2021

Dear Conspiracy Theorist

So let’s start off with where we agree. The mainstream media lies. As a supporter of Julian Assange I watched in horror and disbelief as a brave and principled journalist was traduced for more than a decade by a combination of disinformation, misdirection and blatant lies; as much by the “impartial” BBC, and the “left-wing” Guardian, as by the right-wing papers.

So we can agree on that. But the real measure of how threatening a point of view is to the establishment is how it reacts to the person putting over that point of view. In the case of Julian Assange, he is currently in prison. In the case of David Icke and the other conspiracy theorists, on the other hand, they are still trotting around in public saying all the same stuff they’ve said for years. It’s true that Icke has been banned from Facebook, but he still has many other platforms from which to spread his views; which he does, often, and with great alacrity, popping up on every media platform that will play host to him.

If Icke was really exposing the truth about the great global fascist conspiracy he’s always warning us about, how come he isn’t either dead in a ditch somewhere, or languishing in prison beside Julian Assange?

Why? Maybe because his misinformation actually serves the establishment? Maybe conspiracy theory is all part of a conspiracy to spread disinformation using conspiracy theory?

I’m joking, of course.

I know you don’t like the term “conspiracy theory”. You prefer to think of yourself as a “researcher”. But the research you do all takes place on the internet, which is no more a reliable source than the TV. It, too, is being gamed, from a variety of different sources; including by the far right, for whom deliberate disinformation in order to spread alarm is part of an old play-book, going back to the thirties and beyond.

It was Adolph Hitler who first came up with the phrase “the big lie”. As he said in Mein Kampf: “the broad masses of a nation….. more readily fall victims to the big lie than the small lie.” You like to tell us that the pandemic is the big lie. I would suggest that the idea that the pandemic is a hoax is actually the lie, and that you have bought into it.

We are all conspiracy theorists, to some degree. Governments and corporations definitely do conspire against us. The problem is, by the very nature of the process, no one but the conspirators themselves know what took place. And therein lies the difficulty. You are busy selling us a raft of complex conspiracy theories, but it is all based upon supposition and speculation. You have no actual proof, only theories.

Indeed, some of your theories are contradictory, as, for example, the idea that they want to introduce facial recognition technology while, simultaneously, forcing us to wear masks. Both of those can’t be true at the same time.

I have no objection to you asking questions about the pandemic and about our governments’ handling of it. There is profiteering going on, as a recent Oxfam report made clear, and repressive laws are being enacted. But you seem to have put two and two together and come up with a million. When you say that people will die of the vaccine, and their deaths be blamed upon covid-19, you are spreading misinformation that is likely to put vulnerable people at risk.

I’ve already said I won’t take the vaccine: but that’s because I am resilient and generally resistant to illness. For vulnerable people with underlying health conditions, however, not taking the vaccine could well be a death sentence. By spreading this disinformation you are, at best, causing serious concern to people who are already worried; at worst, some people may well decide not to take the vaccine on the back of the things you say. That is irresponsible of you, and could be a real danger to those people who are naturally scared about what the vaccine might do.

The central problem with conspiracy theory is how divisive it is. It divides the world into Us and Them. You either go along with the conspiracy ideas, or you are excluded. You a “Truther” and the rest of the world are “Sheeple”. You live within your own little conspiracy bubble. It’s a self reinforcing construct as, once you enter it, more and more of your information comes from within that space, and less and less from outside. All of your friends are conspiracy theorists too. There’s a kind of siege mentality. You lose friends from outside the bubble, who don’t want to hear your views, and find yourself inside the conspiracy echo chamber. Your friends think the same way as you. In the end, you lose the capacity for critical thinking altogether.

I won’t take the pandemic as my illustration this time, but I will go back to an earlier theory that also created its own conspiracy bubble at the time: 9/11.

When I met a bunch of anti-lockdown protesters in Canterbury a few weeks back this subject came up. People who believe in pandemic conspiracies tend to believe in 9/11 conspiracies too.

Once again, we can agree on certain things. Is the mainstream view of what happened on 9/11 suspect? Yes. There are all sorts of anomalies, and contradictions, that make it clear that the official story about 9/11 is, at best, absurd, at worst, a fabrication.

I won’t go into that here. There are a million sites that explore that particular theme. What worries me is how, when people have got it into their heads that a particular conspiracy theory is true, they become almost religiously fanatical about it: wanting to prove it to everyone else, and attacking those who disagree with them.

This is exactly what happened in the wake of 9/11. I remember Truthers turning on Robert Fisk, for example – a rare honourable journalist, and no friend of the establishment – because he didn’t believe in their theories and thought that Osama bin Laden probably was behind it. He was called a “shill”. Fisk was entitled to his view, being the last person in the Western media to have interviewed bin Laden.

I also remember people calling Noam Chomsky a “left-gatekeeper” and a “Zionist stooge” and other such insults, because he, too, didn’t buy into the theory.

Get that! Noam Chomsky being derided by a bunch of young Truthers for not being radical enough. Like saying the Pope isn’t Catholic enough, or the Rolling Stones aren’t rock’n’roll enough. Some people have no respect.

The problem is, while we can all agree that we are not well served by our media, and that it is very hard to find the truth, conspiracy theory will always remain just that: theory. It can never be proved so we will never know.

Meanwhile we really didn’t need elaborate conspiracy theories about who blew up the World Trade Centre, when we had actual proof of illegal invasion, torture, extraordinary rendition, support for Islamic terrorism, theft of resources, and the rest.

Likewise, we don’t need grand unprovable and divisive conspiracy theories about the pandemic when we have actual proof of financial malfeasance, corruption and profiteering.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60950c5e2adac', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60950c5e2adac', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

April 29, 2021

Fear and Opportunism

How the pandemic took over the world.

Everyone is afraid. Everyone wants me to be afraid. If you’re not scared of the pandemic, then you’re frightened of the vaccine. If you’re not worried about the third wave, or the Brazilian variant, or concerned about foreign visitors bringing the disease in from other countries, then you’re posting messages on Facebook about the global fascist dictatorship waiting in the wings, working its dark magic, to take over the world.

Continue reading here

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-608a66fbdf256', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', onClick: function() { window.__tcfapi && window.__tcfapi( 'showUi' ); }, } } }); });April 15, 2021

Politics and Spirituality

“A young adult in the 70s”

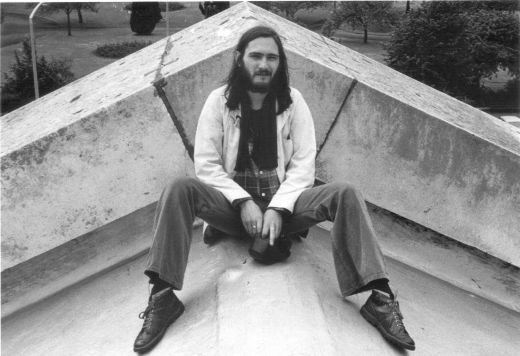

“A young adult in the 70s”I was born in 1953, in Birmingham in the UK, from a typical working class family. My Dad was an electrician, my Mum a hairdresser. Dad was in the Navy when I was born, so I saw very little of him in my early life, although we did go to Malta when I was about 3 or 4 years old, from which I retain certain vivid memories.

So I grew up in that post-war consensus, which saw living standards rise and continue to rise for three decades or more.

I was a child in the fifties, a teenager in the 60s, and a young adult in the 70s.

That was the hippie era, which I’m sure many of you will remember. We did a lot of experimentation. We took a lot of drugs. I took my first LSD with a school mate, it must have been in the summer of 1971, in a park in Birmingham. It was California Sunshine, that very strong, very pure Owsley acid coming out of San Francisco at the time, the seat of hippie culture.

I didn’t really like it, and, to be perfectly honest, I never really got on with acid. It was just too overwhelming, too challenging of the person I thought I was, and I had a number of bad experiences on it.

I went to University in Cardiff in 1971, where I met a couple of people who are still friends to this day.

The early 70s were a time of real political and spiritual ferment, which I’ve written about extensively in my book, The Last of the Hippies. It was a genuinely revolutionary time. If you weren’t in one of the new far-left groups which were just emerging in that era – The Socialist Worker’s Party and the Worker’s Revolutionary Party to name but two – you were joining some other kind of cult, Scientology or the Divine Light Mission. Everybody was looking for something. We were all trying to change the world.

People were dropping out all over the place. That phrase came from Timothy Leary, who, in a famous speech to the Human Be-in, a gathering of 30,000 hippies in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in 1967, told his audience to “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out.”

Later, in 1983 in his autobiography Flashbacks, Leary explained what he meant by the slogan.

“Turn on” meant go within to activate your neural and genetic equipment. Become sensitive to the many and various levels of consciousness and the specific triggers that engage them. Drugs were one way to accomplish this end. “Tune in” meant interact harmoniously with the world around you – externalize, materialize, express your new internal perspectives. “Drop out” suggested an active, selective, graceful process of detachment from involuntary or unconscious commitments. “Drop Out” meant self-reliance, a discovery of one’s singularity, a commitment to mobility, choice, and change. Unhappily my explanations of this sequence of personal development were often misinterpreted to mean “Get stoned and abandon all constructive activity”.

I have to admit that that’s how I understood the instruction. I spent nigh on 18 months in my late teens and early 20s, off my head on dope and other psychoactive substances, listening to rock music, surfing the psychic ocean of relativity, avidly reading books about enlightenment, while being thoroughly unenlightened myself, fracturing whatever sparks of my native intelligence had survived the onslaught.

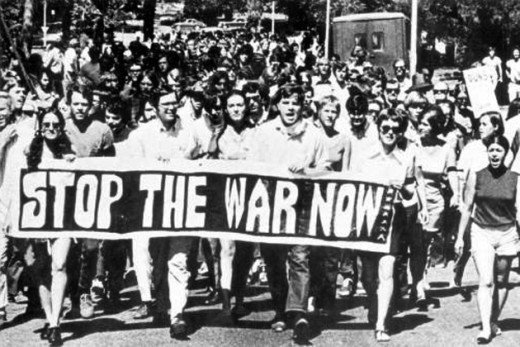

Fracture “Marching against the Vietnam war”

“Marching against the Vietnam war”Something was happening to the hippie movement at the same time. It too, like my brain, was fracturing. In the 60s the urge was revolutionary and the revolution took took two distinct forms. There was a spiritual revolution and a political revolution, but they went hand in hand. People were trying to change the objective world out there, marching against the Vietnam War and joining revolutionary groups; but they were also engaged in a struggle with their inner life, trying to change their subjective world through encounter groups, magic, astrology, the I-Ching. Eastern philosophy was all the rage.

By the 70s these two strands were splitting apart. You were either one thing or the other, either political or spiritual, so if you joined the Divine Light Mission, as one of my friends did, you started talking disparagingly about political engagement, saying things like “the only revolutionary act is to free your mind,” while attending mass events and turning into a spiritual clone.

I went to one of their meetings once, in Acton, and I hated it. Some little kid came up to me and did that thing where they point at your chest and say, “what’s that?” and you look down and they bring their hand up to your chin making you jump and laughing at your stupidity. I thought he was a brat and I looked around to see where his parents were so I could ask them to keep their annoying kid under control, only of course they were too engaged in seeking their own enlightenment to be worried about what their child was up to, which I think was characteristic of the age.

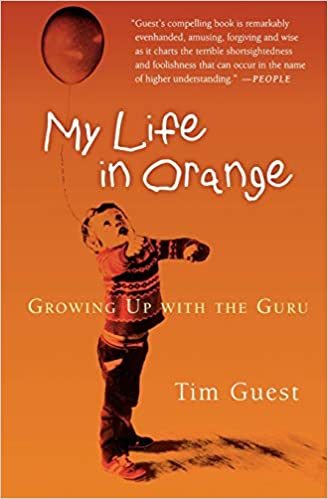

That reminds me of something I heard on the radio a few years back. It was a reading of Tim Guest’s book, My Life In Orange, which is about him growing up in the Rajneesh community, the group we used to call the Orange People. It’s a book I would highly recommend to people of a certain age. There’s one memorable passage in it. Tim was brought up in various communes both in this country and beyond, and his Mum, who was high up in the Sannyasin community was always too busy to spend much time with him. Tim talks about spending a lot of his time in large halls full of people, standing on his tiptoes trying to see where his Mum might be. But he talks about one commune and about how the Sannyasins were always trying to be as egoless as possible. That was the idea. You were supposed to get rid of your ego. And one day there were all sitting round the big table in the kitchen having one of their weekly encounter groups, and – as is the way with communes – there was a lot of rivalry, and Tim overheard a conversation which went a little like this: “I’m more egoless than you are!” “No, I’m more egoless.” Even at the age of five, Tim knew how absurd that conversation was.

But back to my story. I’d been at Uni, but, inspired by Tim Leary’s words, and the actions of various friends of mine, I’d “dropped out.” I left university and went to live with my Auntie Else and Uncle George in Burton on Trent, where I became a dustman. Well it was a summer job. I didn’t see a future of lifting bins ahead of me. But I developed muscles in that time, and a taste for beer. I also used to spend a lot of time talking to my Uncle George. Actually he was my Great Uncle, as Elsie, his wife, was my Nan’s sister. It turned out that they were my God Parents and they saw their role as guiding me in this transitional time in my life. George was a fervent socialist, and Else a promoter of animal rights. She would have been an animal rights activist had she been born a few years later. But it was George who grounded me in my history. He was a rebel, like me. He was a trade unionist and a republican, a Labour activist, and he showed me that my flirtations with rebellious ideas stemmed out of a long history of political engagement going back to the thirties and before.

So that’s how I became a socialist. It was a combination of long conversations with Uncle George, and with a good friend of mine who I’d met at university, who was the nearest thing you could meet to a hereditary Marxist. His family had come from the Valleys in Wales, where they had all been blacklisted as communists.

The reason I’m telling you all this is that there have always been these two strands in my life: the spiritual and the political, a combination of my background, as a child of the post-war consensus, and the era I grew up in, which was an era of experimentation: with drugs, with lifestyles, with music and with literature, and my whole life has been an attempt to reconcile the two.

The Wicker ManSo, to fast forward a few years.

In the 1980s I joined the Labour Party, and I also became interested in paganism.

One of the main inspirations for this was watching the film The Wicker Man.

I had the director’s cut version, which is virtually a musical in that it breaks into song nearly every five minutes. There’s one major sequence in the director’s cut which never made it into the cinema version. In it Edward Woodward, as the Christian cop, is praying by his bedside, having witnessed all these disturbing scenes of promiscuity and public lewdness, while Christopher Lee, as Lord Summer Isle, is delivering a young man to Britt Eckland’s initiatory embrace, while the people in the pub down below are singing “Gently Johnny” in soft voices, and Lord Summer Isle is quoting I Think I Could Turn and Live With Animals by Walt Whitman, while we see cut-away scenes of two slugs making love in slippery ecstasy:

I think I could turn and live with animals,they are so placid and self-contain'd,I stand and look at them long and long.They do not sweat and whine about their condition,They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God,Not one is dissatisfied, not one is demented with the mania of owning things,Not one kneels to another, nor to his kind that lived thousands of years ago,Not one is respectable or unhappy over the whole earth.I must have watched that film a hundred times or more, and I will still watch it again every so often now. It is a remarkable film, and I’m sure I’m not the only one to have developed an interest in paganism from viewing it.

There’s one line that sums it all up for me.

As Lord Summer Isle hands Ash Buchanan into the arms of Willow McGregor, he says, calling up to her window: “Another sacrifice for Aphrodite, Willow.”

“You flatter me your Lordship,” she replies: “Surely you mean to Aphrodite.”

“I make no such distinction,” he says: “You are the goddess of love in human form and I am merely your humble acolyte.”

That’s the line: “I make no such distinction.” That’s what distinguishes paganism from the Abrahamic religions: the idea that divinity may be expressed through humanity, that any of us could be vessels for the divine, if we so choose.

At the same time, in the mid eighties, we had the Miner’s Strike and the attacks upon the New Age Traveller movement in the famous Battle of the Beanfield.

The New Age Travellers were my generation. Many people that I knew back in my student days in Cardiff, had become New Age Travellers. They were the perfect combination of the things I’ve been talking about here: the alliance between the political and the spiritual.

They arose out of the free festival movement of the early 70s. There were four main figures behind this movement: Bill Dwyer, Sid Rawle, Andrew Kerr and Phil Russell, known as Wally Hope.

I wrote about Wally Hope in my book Fierce Dancing, and about Andrew Kerr in The Last of the Hippies. Sid Rawle, unfortunately, blotted his copy book in later years by showing an unhealthy interest in girls young enough to be his grandchildren, and developed a reputation as a sex pest. You wouldn’t want to get into a sweat lodge with Sid if you were female and under a certain age as you would be certain to find yourself being groped by him. I won’t go into that here, although it does shed a certain light upon some of the problems of the age.

Anarchist Bill in Hyde Park, advertising the festival

Bill in Hyde Park, advertising the festival Royal Artillery bade: “Ubique” where Ubi’s name came from

Royal Artillery bade: “Ubique” where Ubi’s name came fromThe first person on my list was Bill Dwyer, also known as Ubi Dwyer, who was the man who started the Windsor Free Festival, which was held over the August Bank Holiday in the years from 1971 to 1974. Bill sort of sums it all up for me.

The name Ubi, by which he was commonly known, was short for Ubique, which means “everywhere”. He got it, so the story goes, from a combat jacket he bought in Camden Market, which had belonged to someone in the Royal Artillery. The jacket had a badge on it, which was in the form of the symbol of the Royal Artillery: a spiral of dots with flames coming out of the top, with the regimental motto “Ubique” written underneath. So you can imagine him looking at this badge while he was tripped out, and all the layers of meaning in it blowing his mind to such a degree that he decided to name himself after it.

Bill was an acid dealer and user as well as a committed anarchist. He was Irish but had travelled the world, living in Australia and New Zealand for a while, where he had sold acid and organised early raves. He was in his forties in the 70s, so a lot older than many of the people he was surrounded by. Pictures show him with long hair and a beard, often riding a bike, smiling broadly , wearing a multi-coloured poncho and a fishing hat with a smiley badge on it. He also contributed to the historic anarchist magazine “Freedom” where he edited and compiled the famous acid edition.

A friend of mine, Wally Dean, refers to the early free festival people as “psychedelic anarchists” and that would be a perfect description of Bill. There’s a bit of film of him, made for an Irish TV programme, probably in 1970, about an Irish commune he was involved in in Dublin, in which he’s berating his fellow commune dwellers for being lazy.

He has a lovely, soft Irish accent and is very articulate. “We are determined, we who founded the group, that it should be a working community,” he says. “And we think, we think, that the alternative to a working community would be a doss house.”

So Bill and the other commune dwellers were obviously having the same difficulties interpreting the meaning of the phrase, Drop Out as I was.

Squats and communes were all the rage in the 70s, but we forget that there is a history to all of this. Living in communes has a long history in anarchist circles, going right back to the last years of the 19th Century, when the spiritual anarchist and novelist, Leo Tolstoy, had set up a commune and lived as a peasant in pre-revolutionary Russia. Tolstoyan communes had sprung up all over the world after that, of which there were a number in Britain, so while commune dwelling was very fashionable in the 70s and 80s, it was anarchist activists, like Bill, who knew their history who were behind it.

The thing about these anarchists is that they were much less doctrinaire than the communists who are their great historical rivals. Communists were and are rigidly materialist, but anarchists are able to adopt a more spiritual outlook as well. Tolstoy was a Christian as well an an anarchist, and Bill Dwyer was not averse to allowing God into his philosophical justifications either.

When he was arrested in 1975, for handing out leaflets despite an injunction against him, he said, “I know I am under an injunction not to organise this festival, but the God I believe in, namely Love, has laid on me a higher injunction to go ahead.”

In fact there’s something quite remarkable about all of these early proponents of the free festival movement, that all of them claimed to have been given their instructions by God. Andrew Kerr, who started the Glastonbury festival in 1971, says that he was lead to Michael Eavis’s door by a series of revelations, Wally Hope saw God in Cyprus while on an acid trip and conceived the Stonehenge free festival, while, according to the stories, Bill Dwyer had had his vision during the Rolling Stones concert in Hyde Park in 1969. He saw a massive gathering of people in Windsor Great Park, on the Queen’s doorstep, on land which had once been common land but which had been appropriated by the Crown. As he told the Kensington Post on the 10th May 1972 his aim was To spark the revolution of LOVE-PEACE-FREEDOM when brothers and sisters shall shout together “we shall never again pay rent!”

He’s talking about squatting. Squatting isn’t just a lifestyle choice to Bill, it’s a spiritual injunction. He sees the gathering not only as an opportunity to raise consciousness, to alter consciousness, but to serve as a political protest against the very notion of private property. In Bill’s world view we free ourselves through spiritual and political action, which are one and the same thing. The result of meeting together on the land, on historically disputed land, and grooving together on acid is to attain love, peace and freedom which will lead inevitably to revolution.

Stonehenge

The last Windsor Free Festival took place in August 1974. It was violently attacked by the police after four days, who stormed through the site wielding truncheons.

By this time, the first ever Stonehenge festival had also taken place, over the summer solstice in the National Trust field across the road from the monument.

After a few failed experiments with other sites, the so-called People’s Free Festival (as Bill and Sid and other’s had referred to Windsor) eventually handed over the baton to Stonehenge.

That festival was to last another ten years and was to spawn a whole lifestyle that has continued to this day.

You may already know the history of this. To my mind it is this festival, more than anything else, which kick starts the modern pagan movement we see today.

You can trace modern druidry back to the 18th century, and Wicca to Gerald Gardner in the 1950s, but the sudden explosion of interest in all things pagan, I feel, arises very strongly out of the free festival movement of the mid 70s to the mid eighties, reinforced again by the road protests of the 90s, which were its spiritual heir.

Certainly some of the key figures in contemporary druidry, like Arthur Pendragon, Rolo Maughfling and Tim Sebastion, were all regular festival goers.

I have my own theories as to why this might have happened.

The Stonehenge festival was a month long affair. It started off very small, but grew and grew as the years went by, till, by 1984 up to a quarter of a million people were attending.

It continued to reflect its anarchist origins, and the most common flag was the anarchist flag, a white circle with an A on a black background, but the site itself must have imposed itself on people’s hearts and minds over the years. Unlike Windsor, there wasn’t the same strong political edge to holding a festival here. One of the early druid groups, the Church of the Universal Bond, lead by George Watson McGregor Reid, a notable eccentric who mixed sun worship and druidry with socialist revolution and anti-imperialism, had first fixed the idea of druids and Stonehenge into popular consciousness in the early 20th century, and George’s son Robert continued to bring druids to the circle throughout the 50s, 60s and 70s, when the festival goers would have seen them.

Amongst their number was William Roache, famous for playing the fictional character Ken Barlow in Coronation Street, and it was one of the festival jokes to go along to the ceremonies on solstice morning and intone “Ken Baaaaaaarloooooow” as a mystical chant along with the druids’s own more elevated incantations.

But, you can’t deny it, Stonehenge casts a spell.

It is evidence that our prehistoric ancestors were profoundly civilised and had a deep cultural understanding of the movement of time and the stars.

I know from my own experience, having visited it regularly on solstice and other nights ever since open managed access was instigated in the year 2000, that there there is a presence there, something profound and mysterious. I don’t think anyone can enter that circle and not feel it. So imagine spending the better part of the month there, every year, year after year, and then moving on, from stone circle to stone circle throughout the summer, as the Travellers were wont to do. Add to this some psychoactive chemistry, nights spent out under the stars, and days in the sunshine, reverting back to a simpler and more organic form of life, cooking on an open fire, meeting new people every year, living in trucks and benders and rediscovering your nomadic roots: living tribally, everyone depending on everyone else, is it any wonder that people were seeking out new ways of looking at the world, new philosophical understandings, and finding these less in the Eastern religions which had informed the hippies a few years earlier, but in something organic which grew out of the British soil. Call it Albionism. It’s as good a word as any.

The Battle of the Beanfield took place 11 years after the first Stonehenge festival, on June 1st 1985.

It was not long after the Miners had been defeated, after their year long strike. Margaret Thatcher had famously referred to them as The Enemy Within. The New Age Travellers had been described as “Medieval Brigands” in the press and it is clear that the Thatcher government and other members of the establishment were fed up with their on going act of collective rebellion at Stonehenge and beyond and had set out to crush the movement.

Which they did, in an act of collective vandalism tantamount to a police riot. There’s a whole chapter on the Battle of the Beanfield in Fierce Dancing. It’s a very emotional chapter.

Criminal Justice BillPart written, with a voiceover by CJ StoneOK, to talk about myself once more: those of you who know me will know that in the 1990s I wrote a column in the Guardian Weekend called Housing Benefit Hill, later brought together in a book.

It was about the council estate that I lived on at the time, with my son Joe. I was a single parent.

The way I came to be writing that was that I wrote two stories about the council estate and then, on the off chance, sent them in to the Guardian, which were then, miraculously, accepted.

Anyone who knows anything about the writing trade in Britain will know that the Guardian never accepts unsolicited manuscripts, but they did on this occasion.

Trouble is, I made a mistake right at the beginning. I was so excited when I heard that my stories would be published, that I told everyone. And, of course, you can’t write about people in a national newspaper without it affecting your relationship with them. So once the stories had started to appear, followed by the inevitable backlash, I stopped writing about the people on my council estate, and I started writing about my friends on other council estates in other parts of the country. I stopped writing about people who didn’t want to be written about, and I started writing about people who did. The early stories are quite dour and unhappy, stories about poverty and loss. The later stories are funnier and lighter. The early stories are about people oppressed by their poverty, the later ones about people who, despite their poverty, still manage to make a life for themselves.

So it was halfway into my first year as a Guardian columnist that the legislation against certain lifestyle choices was being introduced in Parliament. This was the Criminal Justice Bill, which, along with a rag bag of other unrelated issues, also contained legislation against raves, against particular forms of protest, against squatting and against travellers. So I started writing about that in my column too, and became, accidentally, a sort of national spokesman for the movement.

And it was in the process of making a TV documentary about the movement against the Criminal Justice Bill that I came across my first road protest.

This was on Solsbury Hill near Bath. I wrote an extended column about it which appeared under the title “Spirits in a Material World.”

This was the first time I came across a movement which was overtly magical in its terminology, and yet deeply political at the same time.

Here is a short extract:

“THERE was one person I particularly wanted to talk to, and on my last day I managed to secure an interview with Sam of the Donga tribe. She’s a lithe, powerful woman, very dark-skinned, fearsome and brave, as I saw in her actions against the machines. Whether she is really a Queen or not, there is definitely something regal in her bearing.

“We sat by the fire and drank tea, while she told me about her theories. The tribe’s name is taken from the deep ruts or trackways that used to cross Twyford Down. They were worn by the tread of human feet heading for St. Catherine’s Hill, which was the principle meeting place for all the tribes of ancient Europe. In chalk downland especially, she told me, there are deep underground streams, ‘like the veins in my hand.’ This is what people and animals are in tune with. ‘They’re like energy lines, and people follow them to places on the Earth where people are welcome to gather.’

“In these places there’s a special kind of magic. They are sacred. In England these are the Hill Forts, many of them now under threat from the DoT’s road building programme. She has an image of the ancient world as entirely on the move: thousands of tribes treading the trackways or following the trade-routes, ships and carts and the incessant tread of human feet. But something (the ubiquitous they) wants to stop this natural urge to travel and to gather. They buried plague victims in the sacred spots. They put the sewerage works on St. Catherine’s Hill, and then they built the road.

“Who are we talking about exactly? The Freemasons. They are attuned to a negative form of the same energy that the tribes worship. They are actively trying to cut off the Earth’s nervous systems. Why else are they selecting the most beautiful sites for their road programme?

“Sam has many theories that are obviously part of the on-going myth-structure of the movement. She talks of astrological patterns in the landscape, crystal energy, of vast, all-embracing conspiracies; of the circular dance. I’m disinclined to believe most of it, though I support her right to believe anything she likes. But there’s one thing she says which strikes me to the very heart. ‘There was a time when, world-wide, everything was in total harmony, when all the stone-energy was producing euphoric ecstasy of the Earth. She loves all the lovely things that we like – you know: dancing, laughing, sex, music, the whole lot. You know that brilliant feeling when you’re in love with someone special? Well imagine being in love with the whole of the Earth, and every lovely thing in it…’

“A philosophy like that doesn’t have to be true in the strict scientific sense. It’s true enough in the feelings of longing that we all share.”

The Land Road protest at Newbury: “the heir to the Stonehenge free festival”

Road protest at Newbury: “the heir to the Stonehenge free festival”Well all of this was completely new to me, but it really struck a chord. And it was after this that I started following up on all the road protests going on around the country at that time, the early to mid nineties.

They were definitely the heir to the Stonehenge free festival. They utilised some of the same skills: living on the land, building benders and yurts and other low-impact housing, cooking around an open fire, using the squatting laws to stop being evicted. Some of the same people were involved too, like Arthur Pendragon. They also followed on from other protest movements that used occupation of land as a strategy, like the peace camps around Molesworth and Greenham Common, and which continue to this day in the Occupy movement.

But it was the philosophy which really knocked me out. It was like a form of radical animism. It wasn’t pagan in the formal sense, which acts like an alternative religion, with a self-appointed priesthood. There weren’t any priests amongst these people, although there was a lot of mystical speculation going on. It seemed spontaneous, as if it grew out of the very soil on which they were camped. I don’t know what books they were reading, if any. It seemed to me that they were reading directly from nature itself.

Here’s one story which really encapsulates the whole thing for me. I saw one of the protesters sitting on a low wall gazing abstractly at the work going on below him: those huge, heavy-gauge vehicles gnawing at the land and turning it to dust. He’d spoken to one of the workmen earlier, he told me. Do you believe that trees have spirits, he asked? Answer: “No.” Do you believe that animals have spirits? “No.” Do you believe that the Earth has a spirit? “No.” And you: do you believe that you have a spirit? Slight confused pause, then: “No.”

I followed up on these first experiences of the road protest movement by writing a book with Arthur Pendragon, who had been a road protester at the Newbury Bypass protests, amongst other places.

Arthur perfectly encapsulates my interest in this magical-political crossover; although I have to say that writing a book about a guy who says he’s the reincarnation of a mythical King rather spoiled my reputation as a cynical, hard-bitten journalist. My writing career never quite recovered from it, After that I became a postal worker.

What all of this has been about is land. That’s the secret that festival culture reveals to us. We are not separate from the Earth: we are the Earth. Anyone who has attended a festival or a rave and taken a few mind expanding chemicals will know this. There’s a real sense of the Earth awakening beneath our feet, of it responding to the joyous rhythm of our step. Anyone who has been to Stonehenge at the summer solstice will know the sense of the Stones coming alive. Where does consciousness come from? The reductionists will say that it is no more than random electrical signals locked up inside our brain. What those experiences out there on the land teaches us is that we are not isolated at all, that consciousness is all around us: that we breathe it in with the air, that we hear it in the breeze, that we feel it in the grass beneath our feet, that we see it when we lie down on our backs and look into the vast deeps of the cosmic ocean, that we taste it in the water we drink and the food we eat, that we absorb it through every pore in the very process of being alive. Ecstasy doesn’t come from the mind, it comes from the body. It is that joyous shiver of recognition we feel when we embrace the living Earth.

Thus ownership of land is a spiritual as well as a political question.

There are vast tracts of land held in the sole possession of just a few families. 70% of the land in Britain is owned by less than 1% of the population. Britain has the second most unequal distribution of land in the world. And you wonder why it feels so overcrowded at times?

Not being able to access the land is being cut off from the source of our inspiration. Not being able to gather at the sacred places. Not seeing the Earth come alive in the spring and going through its cycles in the course of the year. No longer feeling the rhythm of the year, the vast majority of the population are cut off from the source. We live disconnected, dissociated lives. Dissociation is a form of mental illness. Maybe this might help explain why the whole human race seems to be on the verge of committing ritual suicide right now.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60780c9e014e4', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60780c9e014e4', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

April 8, 2021

Reclaim The Archetypes!

Stonehenge 1984

Stonehenge 1984Two old festival goers meet in a pub, and begin reminiscing about a particular festival. Except that, within ten minutes, they discover that they have no memories in common: not one memory coincides. They know that they were at the same festival on the same date, but beyond that nothing. They remember entirely different things.

“Were we even at the same festival?” one of them asks.

The cliche about the sixties is that whoever remembers them wasn’t there. The line about the free festivals might be: whoever doesn’t remember something utterly unique about them wasn’t there.

The difference between a free festival and a pay festival may appear obvious on the surface. A free festival is free. But, while they have a common origin—the earliest free festivals, such as Woodstock in the United States, and Phun City in the UK, having started as pay festivals that went wrong—the main difference lies in the organisation, there being no overarching structure of control at a free festival, and no profits for the corporations. Thus the differences are immeasurable.

So what is a free festival? It’s a lot of things.

It’s a party. It’s a camping trip. It’s a social gathering. It’s a spiritual occasion. It’s a celebration. It’s a political protest. It’s a rally. It’s a bike rally, a truck rally and a political rally all at the same time. It’s an alternative economy, a market, where you can buy and sell all sorts of things. It’s a craft fair. It’s a place where you can meet new lovers or old friends. It’s a showcase for bands and for alternative technologies. It’s an exercise in collective decision making and collective dreaming. It is the model for a certain type of pop anarchism. It’s an extended family. It’s a cheap holiday. It’s a safe place to bring the kids. It’s a romantic interlude. It binds you to the past and anticipates the future. It’s all of these things and more.

Somebody to LoveInspired partly by the film of Woodstock, which came out in 1970, and by the sequence of free concerts held in Hyde Park during the late sixties and early 70s, the early free festivals were unique affairs.

The slogan for the Windsor Free Festival, one of the earliest, held at Windsor Great Park during the August bank holidays between 1972 and 1974—reclaiming what had once been common land—was “Pay No Rent”. That tells you a lot about what was going on at the time.

In fact, the man who first conceived of the festival, Bill Ubi Dwyer, a civil servant who utilised government copying facilities to publicise the event, saw it in a vision. He saw a mass of people, like a gathering of the tribes, on Crown land. And when attempts were being made to block his progress, by denying him permission, he said: “I personally have God’s permission for the festival.”

This is the stuff of legend, of course. It may or may not have happened. But if it didn’t happen, it ought to have.

And that’s what people seem to remember about the festivals. Something archetypal: something reflecting a mythological dimension, like a stirring from the depths.

As Willow, from Glastonbury, said referring to the Stonehenge festival: “To me it was like a strobe light. You saw the sacred and the profane interacting every minute. On mid-summer’s eve, it would buzz, it was like a dome came down over it, and I saw whirling orange spirals in the sky, and everything became completely archetypal.” And she likened the atmosphere to one of those Goblin Fairs of fairy-stories: a place where anything can happen.

Mythological Trentishoe

TrentishoeDes, also from Glastonbury, agreed.

He was remembering one particular festival.

“Might have been Trentishoe. Right on the North Devon coast. I remember we got there about four in the morning. You couldn’t drive to this place. You had to walk up a track. And I remember as I got to the bottom of the valley with the crest of the hill in front of me, these three people and a goat appeared through the mist, and there was this woman, a very tall Apollonian figure, with long blond hair wearing a loin cloth, and some bloke carrying a big bundle tied up on his back and leading this goat on a lead. They were leaving this festival and walking back up into the world. And it was a bit like something out of Crock of Gold, you know, the James Stevens book. Because it was so mythological. They just seemed so majestic.”

This was deeply impressive to the young man, who set about remaking himself as his own archetype.

It was this quality that separated the festivals from ordinary political events. Because, although there was a political intent, to do with the liberation of private property, born from a specifically anarchist perspective, the events themselves brought up much that was deeply embedded in the human heart.

Not that everything was perfect.

Willow also remembered the biker riot one year at the Stones, when the Hell’s Angels had moved in and attempted to take over. The bikers and the travellers had ended up eyeballing each other across the main drag, until the bikers had backed down. You had to be willing to protect yourself. But in later years the bikers became as much a fixture of the festival as everyone else. Willow had only escaped the fearfulness of the occasion because she was, as she says herself, in fairyland at the time.

Narcissism

Steve, from Cardiff, was also aware of some of the negative aspects of the culture.

He was hitch hiking home from one festival, when he collapsed. “I got to Bristol to an interchange there, and there was a whole queue of people, more festival goers, maybe twenty, thirty odd people lined along the road,” he says. “I’d been walking for hours, it was hot, I was tired, and I must have just flaked out: you know, exhaustion, heat, everything.” He came to several hours later. But what struck him was that the other festival goers hadn’t even checked if he was all right. “I’m thinking, where are all the people, where are all these hippie cool people gone? They all left me here. I could have been dead.”

So there was also a kind of narcissism there. Some people were just too cool to think about anyone but themselves.

Later came the introduction of heroin and cocaine, and the consequent involvement of the criminal fraternity, before ecstasy, Acid House parties and rave entered the picture in the late eighties, reviving the scene again.

The last great free festival was held at Castlemorton Common, near Tewkesbury in the Malvern Hills in May 1992. It lasted about four days and up to 50,000 people attended. There was a big court case afterwards in which fourteen people were charged with “Conspiracy to Cause a Public Nuisance”. Between them, the policing operation and the court case cost the British Taxpayer approaching £5 million. All fourteen people were found Not Guilty. The infamous Criminal Justice Bill of 1994 was enacted precisely to stop this kind of event from ever happening again..

Since then there have been a few other attempts to create a major free festival, most notably The Mother Festival in 1995, effectively splintered by the police into several smaller scale events. And every summer across the country small groups of people still gather to sit beneath the stars, in woods and fields, round an open fire, to revel in each other’s company.

As to whether there will ever be another large scale festival in the United Kingdom: that depends.

It’s down to you.

The Top Five Free Festivals.*

Phun City, July 1970.

Originally conceived as a paying event, organised by Mick Farren of the Social Deviants (later shorted to the Deviants): when the organisation collapsed it turned into the first ever UK free festival. Several bands who had been invited were asked to pay for free. The only band who refused were, ironically, Free. The promo slogan was “Get Your End Away At Phun City!” Top of the bill was the MC5.

Glastonbury Fair, Summer Solstice 1971.

A visionary affair. Organised and paid for by Andrew Kerr, ex Personal Assistant to Randolph Churchill, on Michael Eavis’s dairy farm in Pilton, Somerset, it became the model for all subsequent Glastonbury Festivals. As Kerr said at the time: “If the festival has a specific intention it is to create an increase in awareness in the power of the Universe, a heightening of consciousness and a recognition of our place in the function of this our tired and molested planet.” Whew!

Windsor Free, August Bank Holiday 1972-74.

The last festival was violently attacked by the police, with a number of arrests and several injuries. Such was the negative reaction to this in the press that the police left the festivals alone for over ten years after that.

Watchfield, August Bank Holiday 1975.

Not a particularly good festival, by all accounts, it has the unique historical distinction of being the only free festival in which the British Government collaborated, by providing the site: a disused airfield in Berkshire. A model for the future, perhaps?

Stonehenge, Summer Solstice, 1974-85.

The Mother of all Free Festivals. The longest lasting and best remembered. Started by Phil Russell, aka Wally Hope, after a vision—an experience he shared not only with Bill Dwyer, but with Andrew Kerr too (is this a pattern?) – it was finally stopped in 1985 after the infamous Battle of the Beanfield: effectively a police riot. Gatherings at the Stones on Summer Solstice night resumed in 2000 and continue to this day. No festival, although there have been various attempts to set one up in the vicinity. One day maybe?

Memories of The Pilton Pop festivalFrom The Last of the Hippies, by CJ Stone.

How You Can HelpMake sure you share and like these articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going.Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-606fa7e0238bf', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });April 6, 2021

Metaphysical Monday

Written for the Big Issue 6th March 1999

In case you don’t know, the names of the days of the week are pagan and metaphysical in origin. They are named after celestial beings, mainly Norse, but with one Roman god. So Tuesday is “Tyr’s Day”, Wednesday is “Woden’s day”, Thursday is “Thor’s day”, Friday is “Freya’s day” and Saturday is “Saturn’s day”. Tyr is Woden’s son, the Norse god of war. Freya is Woden’s wife.

By the same token, Sunday is the Sun’s day and Monday is the Moon’s day, both of which are celestial bodies which were once worshipped as deities.

So every day of the week has an underlying metaphysical meaning.

Monday is the worst day, being named after the moon. The light of the moon is simply reflected glory, of course, and moonlight tends to bleed the colour out of things. The moon is connected to lunacy, to moments of dread and confusion and to the urges of the unconscious. In the Tarot-deck a crayfish crawls from a dismal pool while two dogs howl and the moon cries bitter tears. Maybe that’s why Mondays always seem so bad.

Traditionally Monday is washing day. Hence the expression “Blue Mondays”. The blue comes both from the blue dye that was used to whiten whites, and from the fact that it makes you feel blue to spend your whole day scrubbing dirty washing with a wash-board and soap, and then wringing the stuff out with a wringer afterwards. Fortunately these days we have the advantage of automatic washing machines to help out with this onerous task. Well some of us do, anyway. I do now, but I didn’t at the time of this story. I used go to the launderette.

I did consider buying a washing machine. My friend Dodge said he could get me a second hand washing machine for fifty quid, his father-in-law supposedly being a second hand washing machine dealer. Only he forgot. I reminded him, but he forgot again. So I started to think it was probably one of those dodges he is nicknamed for, after his habit of always dodging the question. I started to think that, actually, he couldn’t get me a washing machine after all, and he just didn’t want to admit it. His constant “forgetting” was just a convenient way of not having to say no. After that I enquired about hiring a washing machine instead. I didn’t want to buy a new one as I lived in rented accommodation. I thought that a rented machine wouldn’t be too expensive, and that it would save me the bother of having to move it when I moved house later in the year. Have you ever tried to move a washing machine? They’re loaded with concrete.

I was wrong. It cost more to hire a washing machine than it would to go to the laundrette. The launderette is far cheaper. But it gives you something to do on a Monday morning, doesn’t it, sorting out the washing, and then taking it down the launderette. It’s a way of reflecting on your week.

So that’s where I was on this particular Monday morning: in the launderette, listening to the half-baked banter of the launderette attendant, as she made comments about the newspaper she was reading while smoking a fag. That’s one advantage the launderette has over owning your own washing machine. It gets you out of the house.

The launderette attendant was talking about some Italian bloke who’d won £30.6 million on the Italian state lottery.

“How much?” one of the customers asked.

“Thir-ty-point-six million,” the attendant repeated, emphasising each syllable with precise relish. “He even predicted the order the numbers would come out in.”

The customer said, “how did he do that?”

“Dunno,” she said. “I wouldn’t be working here if I did.”

Meanwhile I was watching my washing shuddering round in the old tumble drier. In the front there was a pink sheet and a green shirt. The two items of clothing completely filled the circular glass screen, twisting round and round each other in a kind of pulsating embrace. I thought that the way the pink sheet and the green shirt wound round on opposite sides looked remarkably like the Yin and Yang sign: like two differently-coloured tadpoles in some strange spinning union. It was my makeshift metaphysical moment, there in the all-too physical launderette. And it reminded me of a time when I was in another launderette, a few years earlier, when I’d ended up in a metaphysical conversation with one of the other customers.

This was in Glastonbury in Somerset. You have metaphysical conversations all over the place in Glastonbury, even in launderettes. The guy was fiddling the tumble drier by putting a 20p coin into one of those extra-thin plastic bags corner shops and green grocers used to supply you with. He was stretching the bag very thinly over the coin, placing the coin in the slot and turning the handle several times before pulling the coin out again. I was watching him, though he was trying to hide it.

“How did you do that?” I asked.

“I shouldn’t tell you. Some kids taught me how to do it,” he said, looking guiltily over his shoulder. “Is it bad Karma to steal, do you think?”

“I dunno. Maybe. But maybe it’s not such bad Karma when you’re ripping off the rip-off merchants,” I suggested. “Who knows?”

He seemed relieved I’d given him the excuse.

“You really think so?” he said. “Only I’m worried about my Karma. I can’t afford to use the driers otherwise.”

“I wouldn’t worry about it if I were you,” I said. “What’s Karma anyway?”

“It’s the cycle of cause-and-effect,” he said. “A bit like this tumble-drier. Round and round and round.”

Well I tried fiddling the tumble-driers too, all these years later in the Whitstable laundrette, when the attendant wasn’t watching. Only it didn’t work for me. There must be a knack. Either that, or I already have bad Karma.