C.J. Stone's Blog, page 3

September 20, 2021

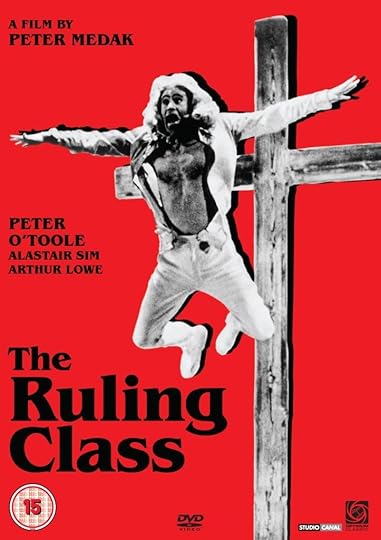

Psychedelic Earl

The Ruling Class is convoluted and dangerous, and never loses sight of its satirical aims.

The Ruling Class is convoluted and dangerous, and never loses sight of its satirical aims.The Ruling Class is a forgotten masterpiece of British cinema. Starring Peter O’Toole and an array of first-class British character actors, it came out in 1972 to mixed reviews. It was never a commercial success. It’s daring, innovative and bleakly humorous. It mixes genres and styles, combining opera with pop, high art with low humor, dazzling sets with clever editing. It breaks out in song and dance at regular intervals, which makes it both entertaining and disturbing. There’s an air of controlled insanity about the whole production.

This is underlined by the plot. The 13th Earl of Gurney (played by Harry Andrews) dies in a bizarre accident while practicing auto-erotic asphyxiation, wearing a tutu, a British military uniform, and a sword. He’s a hanging judge. He leaves his entire estate to his son Jack, a paranoid schizophrenic who thinks he’s God.

It’s worth quoting the opening words of the film, as delivered by the 13th Earl in a speech to the Society of St George (a real-life patriotic organization), as this sets the tone for the movie: “The aim of the Society of St George is to keep green the memory of England. We were once rulers of the greatest empire the world has ever known; ruled, not by superior force or skill, but by sheer presence. I give you England: this teeming womb of privilege, this feudal state, whose shores beat back the turbulent sea of foreign anarchy, this ancient fortress, still commanded by the noblest of our royal blood, this precious stone set in a silver sea…”

After which a toast is raised: “To England, this precious stone set in a silver sea.”

The title sequence is played over a rendition of the national anthem. But not the well-known parts. The least-known verse:

God save our gracious Queen,

Scatter her enemies, and make them fall.

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks,

On thee our hopes we fix,

God save the Queen.

As Lord Gurney gets out of his Rolls Royce on the driveway of his spectacular mansion, he’s greeted by his butler, Tucker (played by Arthur Lowe) who asks how the speech went?

“Went well Tucker. Englishmen like to hear the truth about themselves.”

The acting throughout the movie is impeccable. It’s over-the-top: teetering on the edge of parody, but never quite falling over, and captures the essence of the British ruling class. Every performance is a marvel of expression: from William Mervyn’s Sir Charles, Jack’s pompous uncle, to Alastair Sim’s swivel-eyed Bishop, the parts are played with relish and a peculiar kind of intensity. As British subjects we know these people. We’ve been subjected to their absurd pomposity, their inane sentimentality, their assumption of leadership, the whole of our lives.

Best of all is Peter O’Toole as the alternately fragile and elevated Earl. He plays him as a stoned-out hippie and there’s at least one reference to Timothy Leary, which reminds us of the period in which the film was made.

It’s full of some of the best lines you will ever hear in a movie.

“How do you know you’re God?” the Earl is asked by his eager aunt, early in the film.

“Simple,” he replies. “When I pray to him I find I’m talking to myself.”

The film’s target is, as its title affirms, the ruling class. But not any old ruling class: the British ruling class. No, I take that back. “British” is too broad a word. The British Isles consist of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, plus a host of smaller islands, but they’re decidedly ruled from England. It’s the English ruling class we are talking about: once the rulers of the world.

At the time the film came out the English ruling class were in retreat. They’d become unfashionable. The deferential society was in abeyance. They never lost their power. They never lost their land. They never lost their money, but they had lost their cultural dominance. They’d lost their influence.

Ever since the 1960s, working-class culture had been on the rise. Music was dominated by bands like the Beatles, the Kinks and the Who, working-class lads from the cities. Acting was dominated by working-class actors, like Michael Caine and Terence Stamp, photography and art by David Bailey and Peter Blake, literature by Alan Sillitoe and John Osborne, theater by the likes of Joe Orton, television by Galton and Simpson and Johnny Speight. Even O’Toole was working class, despite that plummy accent of his. Everywhere you looked there were working-class heroes to aspire to and emulate.

So great was the cultural eclipse of the old ruling class that they began to affect working-class mannerisms. Privately-educated Tony Blair, later to become Prime Minister, famously adopted a glottal stop, the replacement of the letter T with a throaty glug, typical of the Cockney accent. Prime Minister David Cameron feigned support for Aston Villa football club.

But it wasn’t to last. The ruling class are back, not only ruling the country, but ruling the arts too. It costs money to buy the equipment to become a pop star. Working people can’t afford it. It costs money to go to art school, to drama college, or to university, and the old grant system has been replaced by loans and fees. You have to pay to get educated these days. There are very few working-class actors, writers, artists or musicians left. It’s the upper classes who dominate our screens and our lives, infiltrating themselves into our consciousness.

The toffs are back on top, more corrupt than ever, fiddling the welfare state to send money to their peers, controlling the airwaves, the flow of news, to keep the proles in ignorance, writing the op-eds in the major papers; running the government, running the economic system, running the justice system, for themselves. And they no longer try to hide where they came from.

Listen to Boris Johnson’s accent. It’s pure Eton-educated superiority, full of huffing bravado and Latin quotations. Johnson doesn’t try to hide his privilege. He revels in it. He wants you to know he was born to rule. He’s exactly like the pompous Sir Charles in the movie. He’ll stop at nothing to maintain his political and economic ascendency.

The English ruling class were once the world’s ruling class. That was in the days of the British Empire. These days they’re subservient to the Americans. It’s American power that dominates. But it’s the English economic and legal system, the English financial system, perpetuated through the City of London and Wall Street, that continues to pull the strings. The English and the American ruling class work hand in hand. Together they plunder the world.

Unfortunately, the ruling class aren’t so easy to remove. Get rid of one lot, and another soon move in to take their place, as the Russians and the Chinese have found to their cost. It’s something inherent in human nature: the desire to dominate, to draw in power for yourself, to steal people’s labour by any means, to feel superior to other people, to want other people to serve you.

The political structure of the world is similar in a way to the psychological structure of an individual. Just as the ruling class rules the economic sphere, so the ego rules the psyche. Just as the ruling class sees itself as the center of the world, so does the ego. We all see ourselves as superior to other creatures, to other human beings, to other denizens of the biosphere. Likewise, the ego dominates our thinking. People lack imagination, empathy and curiosity. They lack creativity. They lack love.

We live within self-reinforcing bubbles of our own illusion. That’s most of us now, with maybe a few rare exceptions. We’re all subject to the ego, which is why the ruling class can dominate us. They know we lust for power, just as they do, so they offer us the illusion of power. They appeal to all that is base and mechanistic in the human psyche. They play upon our weaknesses, our desire to be as they are. We may not want to be Lords of the Manor anymore, but many of us would be celebrities. We dream of winning the lottery, of becoming rich, of being on TV. Therein lies our predictability and our downfall.

It’s the ego and the ruling class between them that are pushing the human race to the edge of extinction. In order to restrain one we have to put constraints upon the other. The opposite of the ego is the community. The community is the place where the ego can be welcomed, then involved. The community not only of all humanity, but of all life too. It’s not political action we need, but community action. It’s not political parties we need, but street parties. We don’t need to grow the economy. Let’s grow our communities instead. The opposite of the ruling class is also the community. Perhaps both problems have the same solution.

—The Ruling Class is available on YouTube, here

Article originally appeared here

August 23, 2021

Guerrilla Gardening in Whitstable

Enjoy the pictures. Pay the sites a visit. Perhaps you might even consider taking up a gardening project of your own?

§

Photographs by Gerry AtkinsonWords by CJ Stone(Click on images to enlarge)

§

St James’ Gardens

St James’ Gardens, with Eva, Theresa and Diane

St James’ Gardens, with Eva, Theresa and DianeMany people in Whitstable will know St James’ Gardens. It’s this dinky little village-like community in the heart of the town. There’s a semi-circular path with a gate at either end, and a number of small one- or two-bedroom bungalows housing mainly elderly or infirm people. It looks like a nice place to live. I imagine it is very neighbourly, with people keeping an eye on each other to make sure everyone is OK.

It was my friend Lesley who alerted me to the small gardening project that is taking place in one of the shrubberies. A number of the women have got together to create a wild flower garden. There are poppies, sunflowers, a buddleia bush, and a number of other plants…

View original post 1,751 more words

Propaganda Pilgrims

A Canterbury Tale links us to more than one pastWhat would our Canterbury pilgrims make of the world we have created since their departure?

A Canterbury Tale is a weird old propaganda film of the 1940s.It was made by the filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who also made The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death and Black Narcissus, among others. It can be found on YouTube and is worth watching, especially for a Canterbury audience, as it includes contemporary shots of bomb sites along Canterbury High Street, where the film comes to an end. It’s a strange mix: part mystery, part history, part spiritual quest, and much of it was shot in and around the villages of Kent, which gives the film a romantic, nostalgic feel.

The plot is ludicrous, involving a mysterious “glue-man” who pours glue over women’s hair after dark. The three central characters meet on the…

View original post 1,702 more words

August 18, 2021

The smallest shop in Kent (possibly)

Mosaic on Harbour Street is probably the smallest shop in Kent. It’s a bit like the Tardis in reverse: seemingly smaller on the inside than on the outside, you duck your head through the door and step down into a Hobbit-cave of ethnic wonder, with a fascinating array of art, clothing and jewellery, all hidden away in two tiny rooms. It’s like stepping into another dimension.

The first time I ever went into the shop Shernaz, the owner, addressed me by name and asked if I had written any more books recently. She had obviously been paying attention.

I met her on the train to London once and we had an engaging conversation about various philosophical matters. It was then that she told me that she came from a Parsi family. I was very impressed.

For those of you who don’t know: the Parsis are the remnants of the ancient Zoroastrian religion who fled to India from Persia after the Muslim takeover.

Their priests were called Magi, which is where we get our word “magic” from. The Three Wise Men of Biblical fame were probably Zoroastrian priests.

Shernaz was born in Calcutta of an Irish Lancastrian mother and a Parsi father. Her mum left when she was two and she was sent to a boarding school run by Catholic nuns in Darjeeling from the age of four. At ten her dad died and she was brought up by an aunt in Mumbai. You could say she’s had a heterodox upbringing.

As a young adult in Mumbai, she ran a column in the local English-language newspaper, and hosted a morning radio programme. She also helped set up an NGO whose mandates were women’s reproductive health and HIV disease control.

She came to Whitstable in 1988 on a visit. Coming down Borstal Hill for the first time, she thought, “I could live here!”

She moved to the town in 1999. She was very open-minded about what she might do for a living and, on the back of her work in Mumbai, applied for a position with one of the local papers. In her interview, she criticised the paper and suggested a number of improvements. The editor said, “You want my job!”

Eventually she settled for opening a fair trade shop utilising stock she got from the women’s cooperatives she had worked with back in India. It was very Indiacentric at first but has since broadened its range to

include any fair trade goods, as well as work by local artists. She also makes and designs stuff herself.

Shernaz remains a campaigner. We went for a walk one day and she was picking up bits of plastic from the beach to turn into art with her grandchildren. Making art out of waste. It’s part of her philosophy.

Mosaic still has ethical sourcing at its root. Shernaz is there most days and is usually willing to stop for a chat about the things she’s interested in.

A woman after my own heart!

For further information go to the Mosaic Facebook page, here: https://www.facebook.com/mosaicwhit/

Story first appeared here.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-611e1ba3a4403', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });Canterbury Bell

I’m sitting in an enclosed garden in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral with my friend Jon. It’s one of our favorite places to sit. There’s a wedding on. The bells of the Cathedral are ringing out in an ecstasy of sound, echoing off the walls that surround us, so that it’s impossible to tell where the noise is coming from. The peal of the bells hangs in the air, poised like ripe fruit from some ancient tree, waiting to be plucked.

The Cathedral was founded in 597 AD by St Augustine, who’d been sent by Pope Gregory I to convert the English. Canterbury is the seat of the Anglican Church, and lies at the heart of the English identity. It’s where the English sense of self was born.

The second track on Nigel Hobbins’ new album Levitating in Lockdown is called “Canterbury Bell.” The “bell” here has several meanings. It’s the bells of the Cathedral ringing out, as they are today, to celebrate some significant moment: a wedding perhaps, or the end of a war. It’s also a wildflower, shaped like a bell. Finally, it’s a beautiful Kent lass, a “Canterbury Belle” in the flower of her youth, heart-stoppingly lovely.

It’s an instrumental, a duet between mandolin and guitar, with a rising, ringing chorus, like the sound of those bells echoing in the Cathedral grounds. Although it’s a new composition, recorded by Hobbins in the heart of the pandemic last year, it’s also immediately recognizable. This is an English tune. It couldn’t have been written anywhere else.

This is Hobbins’ genius. He digs deep into the English soul, the English soil, to find what’s hidden. It’s a kind of musical archaeology. It’s as if these tunes have always existed, and Hobbins has simply found them: as if he has dug them up, cleaned them up, and then presented them to us as if they were new.

The fifth track on the album has a similar quality. Again, it’s named after a flower: the Michaelmas Daisy. Again, it has that air of something found, something old, something profoundly English, something born of the English soil. It’s like a dance tune for an ancient festival, one that lives in the heart of every English person’s soul, immediately recognizable, timeless and yet also brand new.

Hobbins has been doing this for years. From “Glory of a Crown” from his first album, to “Ignore the Rain” from his third, Hobbins captures what’s typically English and turning it into song. For an English person, suffering under the strange spell of these post-Brexit days, this is heartening. To be able to imagine that there’s still something positive to be found in our old country, something worthwhile, something soulful and unique, not yet tainted by craziness, gives us hope of a renaissance yet to come.

The hope lies in the past as well as the future. It’s the sound of English protest in the ghostly and gloriously archaic “Swing Boys Swing,” about the Swing Riots in the 19th century. It’s the sound of childhood and adventure, as well as adult resistance, in the English countryside, in Fighting for the Garden of England. It’s a reminder that the class system is still with us, as we labor under the dictatorship of the Eton Boys, with their plummy, ridiculous accents, their overweening sense of self-entitlement, their politics of blame and division, so well-documented on his latest album:

So if you’re a single mum,or an old person without a pension,if you’re homeless or a traveller on the road,if you’re disabledor been injured in this nation’s conflicts,a protester, gay, black or a refugee,look out for the finger of blame.Hobbins’ view of English identity is inclusive. Hobbins’ England is a welcoming place, a place of communal identity, where our common dreams may thrive. It’s as light and lovely as those flowers he writes about, as welcoming as a dance tune which calls us all to join in. There are no border guards in Hobbins’ country. It’s the land of the Commons, of the common people with our common hopes, common law, common sense, where property is shared through custom not contract, of the common lands where we hold all our festivals, our feast days, by common assent.

This is the strand that runs through all of Hobbins’ music: a sense of shared identity. He sings of the ordinary people, the Lovesick Brickie and the hired worker. He sings of fairgrounds and skinheads, of men coming home from war, of traditional crafts and times gone by. Of love and loss and sadness. Of celebration. Of our ordinary humanity. These themes apply to all of us: to people all over the world. But Hobbins does it in such an English way, it’s a reminder of who the English were meant to be.

Hobbins is one of the most down-to-earth people I know. I’m a city-boy, an itinerant, a nomad who’s been on the move all his life, and I wouldn’t have it any other way, but knowing Hobbins is to know the reassurance of place, of a music and an art that’ve grown out of an abiding presence in one part of the world. It’s the world his parents grew up in, in Challock, just off the Pilgrim’s Way, one of the oldest continuously used roads in the world. The woods behind his house lead to Canterbury. That was his back garden when he was growing up. And it was here, in a summer house he built himself, in the garden of the bungalow his dad built, and that he has tended all his life, that he made all of the recordings that go to make up his latest LP.

Unlike his other albums, this is Hobbins mainly on his own. His usual method of making an LP is to lay down the basic tracks himself, and then to go from house to house, with his recording equipment, to get the contributions of his musical friends. Lockdown made that impossible. What you get on this album is just the basic tracks, plus the sounds of an old Yamaha DX11 from his store cupboard, which he dusted off and which miraculously sprang into life on being plugged in. It’s a pared-down album from a pared-down time.

But it’s that rootedness that comes out most strongly here, not only the rootedness of place, but the rootedness of family too. His Grandad was a pub singer, with a large repertoire of songs, both Music Hall and traditional, that he used to sing to raise money for poor people, as well as for entertainment; and one of these songs, his Mum’s favorite, that his Grandad used to sing to her when his Dad was away at war, is included on the album. It’s a partly unaccompanied song, sung as a message to those who are away to return home safe and sound.

Lastly, my favorite. “River Fishing,” which opens the album, represents everything that’s characteristic about Hobbins’ music. It is, as its title suggests, a song about fishing on a river. The words veer from practical advice about how to fish, to a lonely invocation of the mood, the soul of the practice. It’s evocative of the English countryside, and of the rivers that still wind their way through our green and lovely land. Specifically, it’s about fishing on the River Stour, the river that shimmies and shivers its way through the city of Canterbury on its journey to the sea. This is the same river that lies in the valley beneath where I live, and that I often visit on my walks. A river is wondrous, cool in the heat, with always a breeze, it ripples and sings to you as you pass by. It’s full of life, of river plants that trail and twist like long green tresses, of moorhens and ducks and the occasional family of swans, of fish that hang in the water, half hidden in the depths by their natural camouflage.

This is precisely the feeling you get from Hobbins’ song. The tune—another one of those characteristic English compositions that are his speciality—carries the essence of the river with it. It swirls and shifts with the current. It sparkles with the sunlight. You sense the life of the river in every note. Short of sitting by a river with a fishing rod, watching the sun go down on a late summer’s evening, I can think of no better evocation of this most solitary of pastimes than this song.

—You can listen to the album here, and his entire back catalogue here.

Story first appeared here.

No Mod Cons

Britain produces very little of value anymore. The factories, shipyards, coal fields and steel mills are all closed now, covered over with car parks and supermarkets. What little industry remains is foreign-owned. What’s left? An aging population served by an increasingly resentful youth in the gig economy. There’s not much to be proud of. Whiskey, comedy and youth cults, a few actors, some bands: that’s about it.

One of the interesting aspects of British culture is how it has managed to spread itself throughout the world. Most international sports began in these Isles, even if we no longer have any success in them. Our youth cults, too, have found a wide audience. Japanese rockers, Russian skinheads, Italian goths and American punks have all adopted styles and attitudes born in the United Kingdom.

One of those cults is Mod. Strictly speaking, this was a case of international cross-fertilization. Mods defined themselves in opposition to rockers, who styled themselves on American bikers. Whereas rockers typically wore oil-stained denim, studded leather jackets and greased back hair, the mods wore clean-cut Italian suits and let their hair grow; and while rockers’ lives orbited around their motorbikes, mods went for Italian scooters instead.

The 1960s saw battles on the streets of our seaside towns during bank holiday riots: an early self-assertion of British working-class youth. Mod bands included the Who, the Small Faces, the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds. All of this had become subsumed into hippie culture by the mid-1960s, but mod style was revived later: first by the Jam during the punk era, then by the release of the film Quadrophenia in 1979, based on the rock opera by the Who. Since then, aside from the ongoing popularity of Paul Weller, mod culture seemed mainly to have disappeared.

Until the Sleaford Mods.

Everything about this band is a contradiction. Mod was typically urban. Sleaford is a market town in rural Lincolnshire. The band doesn’t even come from Sleaford. Jason Williamson, the vocalist and lyricist, is from Grantham, where Margaret Thatcher was born. Andrew Fearn, who has composed the music since 2012, is from Burton-on-Trent but grew up on a farm in Saxilby. The band was formed in Nottingham. They don’t look like mods: more like a couple of unemployed middle-aged slackers, up too late to get to the dole office on time.

The music is pared back and functional, centered around computer-generated basslines and no-nonsense, repetitive drum riffs, while the lyrics are dense and idiomatic, delivered in a heavy East Midlands accent, curt, aggressive and full of angry expletives. Williamson doesn’t sing, he rages. He rants. He hammers the words into you with pneumatic intensity. The references are mainly to English working-class life in austerity Britain. Listening to them, even as a native Brit accustomed to the accent, it’s hard to make out what the songs are about.

Imagine my surprise, then, to see a YouTube video of them at a concert in Belgium, with the crowd going wild. The Sleaford Mods are big in Europe it seems… and the United States.

What would you make of lyrics such as these?

This is the four second warning and its gunna scab all your lot

It’s gunna drag you down to Key Markets

And shoot you all in the car park. Key Markets where’s the key?

It’s calling me courtesy counter and bleak me

Green coat and aisles of nothing I got the sack

I thought “fuck me didn’t do nothing obviously”

Fire engine stations bluffing….

Key Markets is the name of a supermarket that used to exist in Britain before it was subsumed into Somerfield. There was one in the Grantham town center when Williamson was growing up. A scab is someone who crosses a picket line. Even with these pointers, it’s hard to make out what the lyrics mean. It seems to be about Williamson’s dismissal from his job in the supermarket before he started making his living in the pop music trade.

That’s assuming anyone actually hears the lyrics, delivered as they are with Williamson’s trademark frantic, tic-riddled intensity, like someone with Tourette’s syndrome cranked up on amphetamines.

The song continues:

You know there’s always better bollocks and they ain’t me

You always know better bollocks on a busy street

I used to rate ’em and now I don’t

I’m just a little moaning arse fart blowing smoke

I’m just a little moaning arse fart blowing smoke

Blowing smoke, oh dear, well excuse me

Blow it up relentlessly

Curbed hole road is endlessly….

“Bollocks” can be used in a variety of ways. “Load of bollocks” is bad. “The dog’s bollocks” is good. In 1977 there was a court case about the use of the word on the cover of the Sex Pistols’ album Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols. The court ruled it wasn’t obscene. It just means “put aside all of that other rubbish and pay attention to this,” the defense barrister said in his summary. Nevertheless, it’s hard to make sense of what Williamson is saying here and how this connects to his sacking from Key Markets.

It’s about an attitude. The attitude translates even when the lyrics don’t. The Sleaford Mods are angry. The music is angry. Even when it has humor, which it often does, it’s angry. This is music to reflect the post-industrial world from which they emerged.

The curses are the language of the streets. It’s how people talk. It’s how Williamson talks. In future years people will study this, not in the way they study Shakespeare, in order to seek the eternal verities, but as a reflection of its age: the age when it appeared as if the world was coming to an end, when the oligarchs were sucking the planet of its wealth while the population stagnated, doing insecure, underpaid jobs on zero-hours contracts, servicing an aging population. It’s music for the service economy. Music for serfs. Music for a generation without a future, bleak and undefined.

It doesn’t care whether you understand it or not. It hardly even understands itself. And you don’t have to understand it to get it. It’s all in Williamson’s voice and delivery. Curt and cut up like a Burroughs text, rhythmically compelling, the voice carries you with it. This is music for broken-down public services and privatized amenities, for boarded-up shops and city centers dying in their own lassitude, for tired graffiti on faded walls, for working class resentment in a world that’s gone awry.

One of their songs is called ”Bang Someone Out.”

Well, I don’t own a bar

I can’t punch nothing

And sometimes I just wanna bang someone out

The days are long, inside I scream

At some of these people they’ve given me

And sometimes I just wanna bang someone out….

This is a threat of violence against an undefined enemy for no discernible reason. He doesn’t care who, and he doesn’t care why, he just wants to “bang someone out.”

Later the song resolves itself:

The plague rolls down from the hills up there

It’s fit for work if it can shit and stare

This is how it’s gone on in the United Kingdom

The plague rolls down from the hills up there

It’s fit for work if it can shit and stare

This is how it’s gone on in the United Kingdom….

Isn’t this the story of everyone’s life in this deteriorating age: the plague of disconnected wealth that infects us all? The meaningless jobs, without value or purpose, which anyone can do and no one wants to. The sense of pointlessness and loss. Williamson specifies the United Kingdom, but this is a plague that infects the world. From Detroit to Derby, from Rotterdam to Rotherham, our world is being destroyed before our eyes, while our identities are stolen and sold back to us as disposable goods in the cut-price supermarket of 21st-century life.

It’s no wonder the Sleaford Mods have gained an audience throughout the world.

Story first appeared here.

July 15, 2021

Whitstable vs Whitstable Oyster Fishery Company

Support Whitstable Beach Campaign at the upcoming public inquiryThe continuing development of industrial-scale farming, ripping apart this delicate ecosystem, is an ongoing threat to an area of national and international importance.

by

*

Fishing for native oysters or farming rock oystersWhitstable is famous for its oysters. The Whitstable Oyster Fishery Company (WOFC) has been in existence since 1793, when it was set up by an Act of Parliament; but, as its name suggests, this was to fish for oysters in the oyster beds far off shore, using dredgers, not to farm them in a semi-industrial process on racks adjacent to the beach.

I’m sure that most people in Whitstable will have seen them. Visitors, too, now comment on the unsightly proliferation of these rusting metal constructions stretched out along the foreshore. They are visible at low tide, first appearing as a series of hooks above the water line as the tide is receding, then slowly revealing themselves more and more as the water shrinks back into the estuary.

In…

View original post 2,725 more words

July 10, 2021

Another England: by CJ Stone

A Review of Levitating in Lockdown by Nigel HobbinsThe spirit of old England, of a spiritual England, another kind of England than the one the advertising men try to sell us.

*

As I’m writing this we’re in the middle of the Euros. England have just won 2-1 against Denmark and football fever is in the air.

The Leader of the Opposition, the Right Honourable Sir Keir Starmer was spotted wearing an England shirt, cheering for the team.

Well I say “spotted”, but it was unlikely that it was accidental. It was much more likely a photo op than a chance encounter. It looked like he had been planning this for weeks.

These days, members of the ruling class have to appear to like football, otherwise people won’t vote for them.

A little while back, after England beat Germany 2-0, pictures of a little German girl appeared all over the internet. She was crying for her team’s loss. England supporters were sharing it about while describing her as a “slut”. She was…

View original post 1,699 more words

July 6, 2021

Written in Stone – Christopher conjures

A dose of Whitstable life, past and present

A dose of Whitstable life, past and presentImoved to Whitstable in 1984. You could call me a DFB – Down From Birmingham – except that the previous place I lived was St Pauls in Bristol. Before that I lived in Humberside, and before that, again, Cardiff, South Wales.

If you look on the map you’ll see that all of these places are on estuaries. I don’t quite know why I am drawn to this particular topography. I guess, coming from a big, old industrial city in the Midlands, it was the openness of the landscape that appealed to me: the big skies and restless seas, the spaciousness and fresh air. When I moved to Whitstable I was immediately at home.

The town I moved into was scruffy, friendly, oldfashioned – and completely undiscovered.

There was a menswear shop on the High Street called Hatchards which was like stepping into the past. It was a haven of old, dark wood, a nest of drawers behind glass counters, with three assistants with tapes around their necks eager to take your measure. They were like living adverts for the stock, kitted out in snazzy waistcoats, with neat ties and shirts with immaculate sleeves and cufflinks.

They sold flat caps and homburgs, trousers with turn-ups, silk cravats, braces, belts, and other accessories, and they would measure your waist for a pair of underpants. You could get all sorts in there: Oxford shirts, leather gloves, long-johns, fleecy pyjamas, all filed away in those drawers which lined the walls from floor to ceiling.

Just up the road at number 37, there was a newsagent stuffed to the rafters with old newspapers and unsold stock from the 60s: jigsaw puzzles, puzzle books and grimy magazines that only the manager would read.

There were – let me think – three bakers, three greengrocers, three butchers, several newsagents, sweet shops, tobacconists, hardware shops, bookshops, electrical shops, furniture shops, clothes shops, and cafés. It was a fully functioning high street. Sadly, few of the shops have survived.

I was talking to Jim on the bus the other day. Jim runs Canterbury Rock in Canterbury. He’s married to Belinda who used to run Herbaceous on Oxford Street, where one of the new barbers has since taken over.

Herbaceous was a unique shop, unlike anything that has been seen before or since. It sold health food, herbs and spices, herbal medicine, bamboo socks, Buddhist statues, incense, incense burners, window decorations, candles and a host of other arcane and interesting items of a distinctly heathen nature.

More than this: it was a gathering place for the whole of the Whitstable community. Belinda was like the oracle of Oxford Street. You would go there to consult her on the auguries. She knew everything that was happening in the town and it was impossible to pass her shop without popping in for a chat. She was forced to close after 17 years, once her rent had gone up beyond what she could afford.

These days Belinda is one of the trustees for the Stream Walk Community Garden. Still keeping the community spirit. Still reading the auguries. Let’s hope it stays that way.

Originally appeared here

June 14, 2021

A non-existent parrot

*

In the 90s I lived in London with my sister. This was in Charlton, near Greenwich. At the same time I had a column in the Big Issue. It was literally a column: the whole length of the page, one column wide, appearing on the outer edge. It was called, naturally enough, “On The Edge”.

It had a black and white picture of me at the top, with long hair and a beard, laughing into the camera’s eye. It was tight cropped, so all you could see was my face, framed by my hair. It was mischievous picture. I had a mischievous grin on my face.

Very soon after moving to London I started to get recognised. It was my only moment of fame. People would see me on the street, or on the tube, or in a pub somewhere, and clock me. They would do a double-take. They’d look, and then look again. Occasionally they would even talk to me.

An observational point: when someone recognises you their pupils grow large. It’s like the pupils open up just that little bit to take in more light, like the brain needs confirmation of what the eye’s just seen and increases the pupil size to take in more light in order to get more information.

One day it was this handsome young black dude with braids in his hair, called Antonio. He said, “are you a writer or something? Do you write for the Big Issue?” We spent a pleasant 15 minutes or so on the train to Lewisham, and that was that. I enjoyed that little taste of recognition, not least because it whiled away a brief moment of time on an otherwise boring train journey.

Later there was a man in a pub I’d taken to frequenting, in Charlton Village. He’d look at me and his pupils would go huge, like deep, black pools in his eyes. He kept staring at me. I was waiting for the inevitable question, the one asked by Antonio, and a few others since arriving in London: “Do you write for the Big Issue?”

Instead he said, “look at the state of you.”

“Whaddya mean?” I said.

“You should get your hair cut, you cunt,” he said.

There’s not much you can say to that. This went on for weeks. He’d stare at me, his pupils would expand, and he’d make some unexpected comment.

Eventually I confronted him. “Why do you keep staring at me? Do you think you know me or something?”

“’Course I do,” he said. “Years ago. You sold me a parrot.”

“What!?”

“A parrot. You remember. A parrot. Red and white thing. Beady eyes. Used to bite my finger. I taught it to swear. You remember.”

It was a statement not a question. I had no idea what he was talking about.

“Listen,” I said, “I’ve never had a parrot in my life, let alone sold one, let alone to you. I’ve only just moved to London, and I never saw you outside this pub.”

“Well you must have a twin,” he said. “I’m sure I bought a parrot from you.”

“Sorry mate, I think you’re thinking of someone else.”

So that was it, the only brief moment of fame in my life and all it turned into was a conversation about a non-existent parrot…

How You Can HelpMake sure you share and like these articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going.Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/ https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60c86a9a4e8bb', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/ __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-60c86a9a4e8bb', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });