David Morley's Blog, page 21

July 2, 2012

The Gypsy and the Poet - images and experiments by David Morley

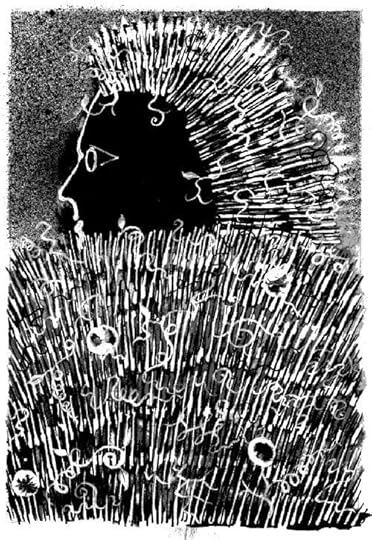

In my last poetry collection "Enchantment" I asked Peter Blegvad to come up with images that would intervene in the book, proving breathing spaces between sections and textural moods. If you know the book you will know he came up with great work (see PB's 'Hedgehurst', left).

Well, my new poetry book is completed.

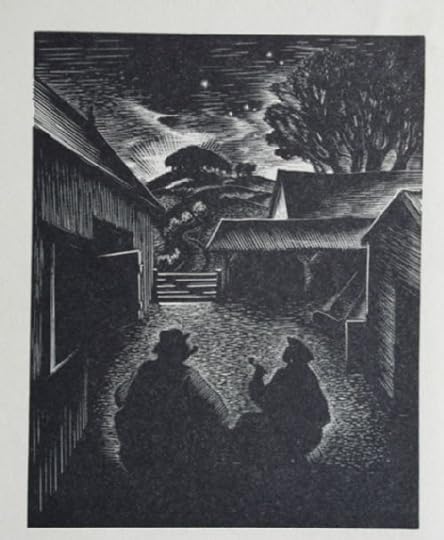

It is called "The Gypsy and the Poet" and once again I am thinking about images that will work with the poems, not illustrating them - but extending from the poems in some manner that enhances and deepens the tone of the whole book, the conversation between the poems, and between the poems and their readers.

I need to experiment with images on the blog for the next few entries and am meeting with Peter again next Wednesday. What do you think of these? What do they say to you? What might they evoke or invoke?

June 14, 2012

Judging the 2012 T.S. Eliot Prize by David Morley

I am delighted to be one of the judges of this year's T.S. Eliot Prize for poetry. I am also honoured. Eliot was one of the first poets whose work was read aloud to me by one of my early mentors. The poetry has stayed with me ever since.

T S Eliot Prize 2012

The Poetry Book Society is delighted to announce the judges for the 2012 T S Eliot Prize for Poetry. Carol Ann Duffy will be Chair and the other two judges will be poets Michael Longley and David Morley.

The judges will meet in October to decide on the ten-book shortlist. The four Poetry Book Society Choices from 2012 are automatically shortlisted for the Prize. The Spring 2012 Choice was The Death of King Arthur by Simon Armitage (Faber) and the Summer Choice was The Dark Film by Paul Farley (Picador). They will be joined on the shortlist by the PBS Autumn Choice, Place by Jorie Graham (Carcanet), and the Winter Choice, which will be announced in August.

The T S Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings will take place on Sunday 13 January 2013 in the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall. The 2010

Readings

were held in this new venue for the first time and were a great artistic and audience-building success, attracting 2,000 poetry lovers, one of the biggest audiences for a single poetry event of recent times. The winner of the 2012 Prize will be announced at the award ceremony on Monday 14 January 2013, where the winner will be presented with a cheque for £15,000, donated by Mrs Valerie Eliot, who has generously given the prize money since the inception of the Prize. The shortlisted poets will each receive £1,000.

The T S Eliot Prize Reading Groups scheme will enable reading groups and individual readers to read the shortlist. Specially commissioned reading group notes, together with three poems from each shortlisted collection, will be made available to download from the PBS website. The scheme will target both poetry reading groups and fiction book groups.

The T S Eliot Prize Shadowing Scheme, run by the Poetry Book Society in partnership with the English and Media Centre’s emagazine, will offer A level students a chance to engage with the latest new poetry by shadowing the judges and taking part in a writing competition.

Last year’s winner was John Burnside for his collection Black Cat Bone (Cape). The judges were Gillian Clarke (Chair), Stephen Knight and Dennis O’Driscoll.

The T S Eliot Prize was inaugurated in 1993 to celebrate the Poetry Book Society's 40th birthday, and to honour its founding poet. Now celebrating its twentieth year, the T S Eliot Prize is the ‘world’s top poetry award’ (Louise Jury, The Irish Independent). The Prize is awarded annually to the writer of the best new poetry collection published in the UK or Ireland. It is unique as it is always judged by a panel of established poets and it has been described by Sir Andrew Motion

as ‘the Prize most poets want to win’.

Previous winners (in chronological order) are: Ciaran Carson,

Paul Muldoon

, Mark Doty, Les Murray, Don Paterson, Ted Hughes, Hugo Williams, Michael Longley, Anne Carson, Alice Oswald, Don Paterson (for the second time), George Szirtes, Carol Ann Duffy

, Seamus Heaney, Sean O’Brien, Jen Hadfield, Philip Gross, Derek Walcott and John Burnside.

The Prize is generously supported by the T S Eliot Estate.

This year marks the second year of generous three-year support from Aurum, a private investment management firm which manages funds for charities, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and private individuals, and which supports a range of charities.

… ends

For further information please go to http://www.poetrybooks.co.uk/projects/4/

Or contact: Dave Isaac or Chris Holifield at the Poetry Book Society

tel 020 7831 7468 emails david_isaac@poetrybooks.co.uk, and chris@poetrybooks.co.uk

Notes

Judges’ Biographies

Carol Ann Duffy

Poet Carol Ann Duffy was born in 1955 in Glasgow

. Her poetry collections include Standing Female Nude (1985); The Other Country (1990); Mean Time (1993), which won the Whitbread Poetry Award and the Forward Poetry Prize; The World’s Wife (1999); Feminine Gospels (2002); and Rapture (2005), which won the 2005 T S Eliot Prize. Her latest collection, The Bees (2011), was shortlisted for the 2011 Prize. Her children’s poems are collected in New & Collected Poems for Children (2009). Carol Ann Duffy is the Poet Laureate. She lives in Manchester

and is Creative Director of the Writing

School

at Manchester

Metropolitan

University

.

Michael Longley

One of Ireland’s foremost contemporary poets, Michael Longley CBE was born in 1939. Longley’s 1991 collection, Gorse Fires, won the Whitbread Poetry Prize. Subsequently, The Weather in Japan (2000) won the Irish Times Literature Prize for Poetry, the Hawthornden Prize and the 2000 T S Eliot Prize. Longley’s recent publications include Snow Water (2004) and Collected Poems (2006). His latest collection, A Hundred Doors (2011) was a PBS Recommendation. In 2001 he was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. Michael Longley is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and he was Ireland Professor of Poetry from 2007 to 2010.

David Morley

An ecologist by background, David Morley’s poetry has won many awards. His most recent poetry collection Enchantment (2010) was a Sunday Telegraph Book of the Year chosen by Jonathan Bate. The Invisible Kings (2007) was a PBS Recommendation and TLS Book of the Year chosen by Les Murray. His next book World’s Eye is due from Carcanet in 2013 followed by his Selected Poems in 2014. A leading international advocate of creative writing, David wrote The Cambridge Introduction to Creative Writing (2007) and co-edited The Cambridge Companion to Creative Writing (2012). He is Professor of Writing at the University

of Warwick

. His website is www.davidmorley.org.uk.

May 29, 2012

'Language ought to be the joint creation of poets and manual workers' - Orwell by David Morley

[image error]

May 14, 2012

It is to keep the lightning out by David Morley

The common cormorant or shag

Lays eggs inside a paper bag.

The reason you will see, no doubt,

It is to keep the lightning out.

But what these unobservant birds

Have never noticed is that herds

Of wandering bears may come with buns

And steal the bags to hold the crumbs.

May 13, 2012

In Just Spring by David Morley

Birds on Warwick University recorded on campus 13th May 2012: Blackbird, Blackcaps (nesting), Reed Bunting, Great Spotted Woodpecker, Song Thrush, Crow, Rook, Magpie, Starling, Greylag Goose (chicks), Canada Goose (chicks), Coot (chicks), Mallard (chicks), Moorhen (chicks), Swallow, House Martin, Common Gull, Green Woodpecker, Grey Heron, Wren, Tufted Duck, Great Crested Grebe, Blue Tit, Great Tit, Long-tailed Tit, Chiffchaff, Robin, Woodpigeon.

Birds on Warwick University recorded on campus 13th May 2012: Blackbird, Blackcaps (nesting), Reed Bunting, Great Spotted Woodpecker, Song Thrush, Crow, Rook, Magpie, Starling, Greylag Goose (chicks), Canada Goose (chicks), Coot (chicks), Mallard (chicks), Moorhen (chicks), Swallow, House Martin, Common Gull, Green Woodpecker, Grey Heron, Wren, Tufted Duck, Great Crested Grebe, Blue Tit, Great Tit, Long-tailed Tit, Chiffchaff, Robin, Woodpigeon.

February 27, 2012

We love the things we love for what they are: Hyla Brook by Robert Frost by David Morley

BY June our brook’s run out of song and speed.

Sought for much after that, it will be found

Either to have gone groping underground

(And taken with it all the Hyla breed

That shouted in the mist a month ago,

Like ghost of sleigh-bells in a ghost of snow)—

Or flourished and come up in jewel-weed,

Weak foliage that is blown upon and bent

Even against the way its waters went.

Its bed is left a faded paper sheet

Of dead leaves stuck together by the heat—

A brook to none but who remember long.

This as it will be seen is other far

Than with brooks taken otherwhere in song.

We love the things we love for what they are.

February 10, 2012

The Story of The Writers

See that telescope in the middle of this photograph?

This powerful Russian telescope, currently on loan to The Writers’ Room at Warwick University, has been on a fascinating literary journey.

In the early 1990s it was acquired by the poet Simon Armitage. Scanning the night skies above his native Huddersfield, Simon began writing a sequence of fifty poems. The titles were taken from the constellations he observed through this telescope’s lenses. However, his poems did not take stellar observation as subject. Cunningly, Simon used the names of the stars and their configurations to stimulate personal poems about family, relationships, work and loss. These poems were published in his collection Cloudcuckooland which he read from at Warwick

University

in 1999.

During the early part of the 21st century, Simon sold the telescope to the novelist Monique Roffey. Monique was then working as Centre Director of the Arvon Foundation at Totleigh Barton in Devon. Monique used the telescope to examine the brilliantly dark skies of Devon and gain inspiration.

The telescope occupied the Arvon Foundation offices for many years, sometimes being used to prompt poetry and stories during the weekly creative writing courses that took place at the centre. Many writers pass through the doors of Arvon at Totleigh; and hundreds of authors will have “played about with”, or used, this telescope during that fertile period in its journey. During this period David Morley taught a number of Arvon writing courses and greatly admired what he then christened the Armitagescope a.k.a. the Roffeyscope.

Later, Monique Roffey left Arvon and became a full-time writer, taking the telescope with her. She moved to central

London

, to the famous Black Sheep Co-op, and wrote the fiction (and non-fiction) that made her name and led her, later that decade, to become one of our most renowned and generous writers.

In 2005, Monique contacted David Morley to explain she was moving on to her own flat, and the telescope was too bulky to make the trip. It might have faced a sad end. So, Monique and DM arranged a ‘gift economy’ exchange: Monique wished to learn how to write poems with a little guidance from DM, and in exchange DM would adopt the telescope so long as he could somehow get to and through

London

, rebuild it and collect it. Which he did. One memorable rainy Sunday morning in Spring.

The telescope needed some TLC by this time. DM reconditioned the lenses, cleaned the scope inside and out, and gave it a coat of paint for good luck. The telescope then lived in DM’s writing studio for six years, making occasional sorties into his garden to study The Great Galaxy of Andromeda. These studies led to the creation of an elemental poetry workshop ‘Nightfishing for Poets’ which examines the universe and how various phenomena within it have acted as templates for the making of oral ‘literature’ in the shape of creation myths.

DM believes Warwick University's Writers’ Room is the natural home for this historical piece of literary-scientific equipment. It is not a theatre prop. It is not trivial. It is a powerful Russian. Deep space. Telescope.

And it can see the face of God.

The Story of The Writers

See that telescope in the middle of this photograph?

This powerful Russian telescope, currently on loan to The Writers’ Room at Warwick University, has been on a fascinating literary journey.

In the early 1990s it was acquired by the poet Simon Armitage. Scanning the night skies above his native Huddersfield, Simon began writing a sequence of fifty poems. The titles were taken from the constellations he observed through this telescope’s lenses. However, his poems did not take stellar observation as subject. Cunningly, Simon used the names of the stars and their configurations to stimulate personal poems about family, relationships, work and loss. These poems were published in his collection Cloudcuckooland which he read from at Warwick

University

in 1999.

During the early part of the 21st century, Simon sold the telescope to the novelist Monique Roffey. Monique was then working as Centre Director of the Arvon Foundation at Totleigh Barton in Devon. Monique used the telescope to examine the brilliantly dark skies of Devon and gain inspiration.

The telescope occupied the Arvon Foundation offices for many years, sometimes being used to prompt poetry and stories during the weekly creative writing courses that took place at the centre. Many writers pass through the doors of Arvon at Totleigh; and hundreds of authors will have “played about with”, or used, this telescope during that fertile period in its journey. During this period David Morley taught a number of Arvon writing courses and greatly admired what he then christened the Armitagescope a.k.a. the Roffeyscope.

Later, Monique Roffey left Arvon and became a full-time writer, taking the telescope with her. She moved to central

London

, to the famous Black Sheep Co-op, and wrote the fiction (and non-fiction) that made her name and led her, later that decade, to become one of our most renowned and generous writers.

In 2005, Monique contacted David Morley to explain she was moving on to her own flat, and the telescope was too bulky to make the trip. It might have faced a sad end. So, Monique and DM arranged a ‘gift economy’ exchange: Monique wished to learn how to write poems with a little guidance from DM, and in exchange DM would adopt the telescope so long as he could somehow get to and through

London

, rebuild it and collect it. Which he did. One memorable rainy Sunday morning in Spring.

The telescope needed some TLC by this time. DM reconditioned the lenses, cleaned the scope inside and out, and gave it a coat of paint for good luck. The telescope then lived in DM’s writing studio for six years, making occasional sorties into his garden to study The Great Galaxy of Andromeda. These studies led to the creation of an elemental poetry workshop ‘Nightfishing for Poets’ which examines the universe and how various phenomena within it have acted as templates for the making of oral ‘literature’ in the shape of creation myths.

DM believes Warwick University's Writers’ Room is the natural home for this historical piece of literary-scientific equipment. It is not a theatre prop. It is not trivial. It is a powerful Russian. Deep space. Telescope.

And it can see the face of God.

The Story of The Writers

See that telescope in the middle of this photograph?

This powerful Russian telescope, currently on loan to The Writers’ Room at Warwick University, has been on a fascinating literary journey.

In the early 1990s it was acquired by the poet Simon Armitage. Scanning the night skies above his native Huddersfield, Simon began writing a sequence of fifty poems. The titles were taken from the constellations he observed through this telescope’s lenses. However, his poems did not take stellar observation as subject. Cunningly, Simon used the names of the stars and their configurations to stimulate personal poems about family, relationships, work and loss. These poems were published in his collection Cloudcuckooland which he read from at Warwick

University

in 1999.

During the early part of the 21st century, Simon sold the telescope to the novelist Monique Roffey. Monique was then working as Centre Director of the Arvon Foundation at Totleigh Barton in Devon. Monique used the telescope to examine the brilliantly dark skies of Devon and gain inspiration.

The telescope occupied the Arvon Foundation offices for many years, sometimes being used to prompt poetry and stories during the weekly creative writing courses that took place at the centre. Many writers pass through the doors of Arvon at Totleigh; and hundreds of authors will have “played about with”, or used, this telescope during that fertile period in its journey. During this period David Morley taught a number of Arvon writing courses and greatly admired what he then christened the Armitagescope a.k.a. the Roffeyscope.

Later, Monique Roffey left Arvon and became a full-time writer, taking the telescope with her. She moved to central

London

, to the famous Black Sheep Co-op, and wrote the fiction (and non-fiction) that made her name and led her, later that decade, to become one of our most renowned and generous writers.

In 2005, Monique contacted David Morley to explain she was moving on to her own flat, and the telescope was too bulky to make the trip. It might have faced a sad end. So, Monique and DM arranged a ‘gift economy’ exchange: Monique wished to learn how to write poems with a little guidance from DM, and in exchange DM would adopt the telescope so long as he could somehow get to and through

London

, rebuild it and collect it. Which he did. One memorable rainy Sunday morning in Spring.

The telescope needed some TLC by this time. DM reconditioned the lenses, cleaned the scope inside and out, and gave it a coat of paint for good luck. The telescope then lived in DM’s writing studio for six years, making occasional sorties into his garden to study The Great Galaxy of Andromeda. These studies led to the creation of an elemental poetry workshop ‘Nightfishing for Poets’ which examines the universe and how various phenomena within it have acted as templates for the making of oral ‘literature’ in the shape of creation myths.

DM believes Warwick University's Writers’ Room is the natural home for this historical piece of literary-scientific equipment. It is not a theatre prop. It is not trivial. It is a powerful Russian. Deep space. Telescope.

And it can see the face of God.

The Story of The Writers� Room Deep Space Telescope by David Morley

See that telescope in the middle of this photograph?

This powerful Russian telescope, currently on loan to The Writers’ Room at Warwick University, has been on a fascinating literary journey.

In the early 1990s it was acquired by the poet Simon Armitage. Scanning the night skies above his native Huddersfield, Simon began writing a sequence of fifty poems. The titles were taken from the constellations he observed through this telescope’s lenses. However, his poems did not take stellar observation as subject. Cunningly, Simon used the names of the stars and their configurations to stimulate personal poems about family, relationships, work and loss. These poems were published in his collection Cloudcuckooland which he read from at Warwick

University

in 1999.

During the early part of the 21st century, Simon sold the telescope to the novelist Monique Roffey. Monique was then working as Centre Director of the Arvon Foundation at Totleigh Barton in Devon. Monique used the telescope to examine the brilliantly dark skies of Devon and gain inspiration.

The telescope occupied the Arvon Foundation offices for many years, sometimes being used to prompt poetry and stories during the weekly creative writing courses that took place at the centre. Many writers pass through the doors of Arvon at Totleigh; and hundreds of authors will have “played about with”, or used, this telescope during that fertile period in its journey. During this period David Morley taught a number of Arvon writing courses and greatly admired what he then christened the Armitagescope a.k.a. the Roffeyscope.

Later, Monique Roffey left Arvon and became a full-time writer, taking the telescope with her. She moved to central

London

, to the famous Black Sheep Co-op, and wrote the fiction (and non-fiction) that made her name and led her, later that decade, to become one of our most renowned and generous writers.

In 2005, Monique contacted David Morley to explain she was moving on to her own flat, and the telescope was too bulky to make the trip. It might have faced a sad end. So, Monique and DM arranged a ‘gift economy’ exchange: Monique wished to learn how to write poems with a little guidance from DM, and in exchange DM would adopt the telescope so long as he could somehow get to and through

London

, rebuild it and collect it. Which he did. One memorable rainy Sunday morning in Spring.

The telescope needed some TLC by this time. DM reconditioned the lenses, cleaned the scope inside and out, and gave it a coat of paint for good luck. The telescope then lived in DM’s writing studio for six years, making occasional sorties into his garden to study The Great Galaxy of Andromeda. These studies led to the creation of an elemental poetry workshop ‘Nightfishing for Poets’ which examines the universe and how various phenomena within it have acted as templates for the making of oral ‘literature’ in the shape of creation myths.

DM believes Warwick University's Writers’ Room is the natural home for this historical piece of literary-scientific equipment. It is not a theatre prop. It is not trivial. It is a powerful Russian. Deep space. Telescope.

And it can see the face of God.

David Morley's Blog

- David Morley's profile

- 13 followers