David Morley's Blog, page 20

December 20, 2012

My Elizabeth Jennings story (because it is Christmas) by David Morley

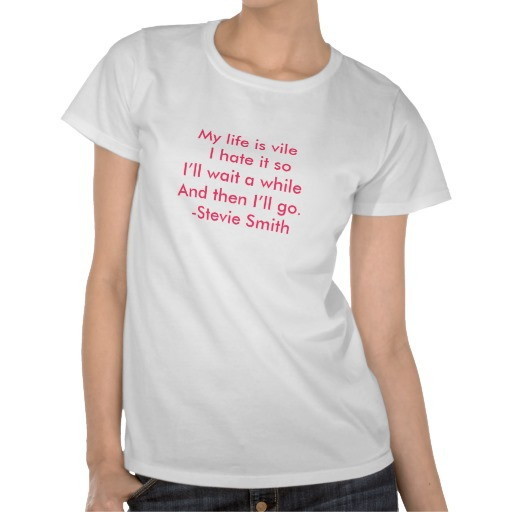

I liked Elizabeth Jennings and I like her poems. When I was 30 I directed my first poetry festivals. While programming I made a decision to ask women poets to read at most of the events. I drew no attention to this engaging balance. I thought the programming made its own point. At one festival, of the 24 poets performing, 21 were women poets. The three men were programmed into one event of their own which I called “Three Male Poets”. I bought myself a Stevie Smith tee-shirt and set about hosting (my tee-shirt bore a photo of Stevie Smith; there are edgier versions available; see image below). The main performance space was a little… well, it was dull. So, using what came to hand from skips and photocopiers and craft shops, I built a high, wide self-standing frieze of poems, images and images of women poets of the last three centuries. This provided a lively backdrop to the performance area, and gave better lighting and perspective for performer and audience. What happened next? The readings were packed. Sometimes I had to turn people away. And they were really angry at being turned away. Why? Because some of the women poets I had booked simply did not get asked to do readings because these women were – women and some were old. Thus, these readings were rare appearances. In fact, there was a mini-riot before the reading by Elizabeth Jennings because of numbers trying to press in through the door. I had met Elizabeth from the train three hours earlier. Immediately we clicked. She jabbed her finger to my chest. ‘You’re wearing my *friend*!!!’ . Anyway, I introduced her to the keen, standing-room-only audience. She rose to the occasion and read with clarity, magic and total power. As the reading went on so more people took advanta

programming I made a decision to ask women poets to read at most of the events. I drew no attention to this engaging balance. I thought the programming made its own point. At one festival, of the 24 poets performing, 21 were women poets. The three men were programmed into one event of their own which I called “Three Male Poets”. I bought myself a Stevie Smith tee-shirt and set about hosting (my tee-shirt bore a photo of Stevie Smith; there are edgier versions available; see image below). The main performance space was a little… well, it was dull. So, using what came to hand from skips and photocopiers and craft shops, I built a high, wide self-standing frieze of poems, images and images of women poets of the last three centuries. This provided a lively backdrop to the performance area, and gave better lighting and perspective for performer and audience. What happened next? The readings were packed. Sometimes I had to turn people away. And they were really angry at being turned away. Why? Because some of the women poets I had booked simply did not get asked to do readings because these women were – women and some were old. Thus, these readings were rare appearances. In fact, there was a mini-riot before the reading by Elizabeth Jennings because of numbers trying to press in through the door. I had met Elizabeth from the train three hours earlier. Immediately we clicked. She jabbed her finger to my chest. ‘You’re wearing my *friend*!!!’ . Anyway, I introduced her to the keen, standing-room-only audience. She rose to the occasion and read with clarity, magic and total power. As the reading went on so more people took advanta ge of the fact we were all listening to Elizabeth to sneak in through doors and windows. By the time she came to read her final poem the room was overfull. And the audience exploded with applause when she finished. So enthusiastically! Their rapture took Elizabeth Jennings by surprise and she slipped and fell backwards. With a puma’s speed (I was 30), I was under her, breaking her fall and catching her in my arms. The applause grew louder. But as I caught her we both collided with the ‘high, wide self-standing frieze of poems, images and images of women poets of the last three centuries’. This wall of wonders trembled for a second and then, like the finale of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, collapsed around us. ‘Like an allegory’, cried Elizabeth Jennings. And the audience exploded again - and picked her out of my arms - and carried her away to be loved and adored like the hero she was.

ge of the fact we were all listening to Elizabeth to sneak in through doors and windows. By the time she came to read her final poem the room was overfull. And the audience exploded with applause when she finished. So enthusiastically! Their rapture took Elizabeth Jennings by surprise and she slipped and fell backwards. With a puma’s speed (I was 30), I was under her, breaking her fall and catching her in my arms. The applause grew louder. But as I caught her we both collided with the ‘high, wide self-standing frieze of poems, images and images of women poets of the last three centuries’. This wall of wonders trembled for a second and then, like the finale of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, collapsed around us. ‘Like an allegory’, cried Elizabeth Jennings. And the audience exploded again - and picked her out of my arms - and carried her away to be loved and adored like the hero she was.

October 23, 2012

Shortlist for 20th T.S. Eliot Prize Announced by David Morley

Judges Carol Ann Duffy (Chair), Michael Longley and David Morley

have chosen the shortlist from the record number of 131 books submitted by publishers.

Simon Armitage The Death of King Arthur Faber

Sean Borodale Bee Journal Jonathan

Cape

Gillian Clarke Ice Carcanet

Julia Copus The World’s Two

Smallest Humans Faber

Paul Farley The Dark Film Picador

Jorie Graham P L A C E Carcanet

Kathleen Jamie The Overhaul Picador

Sharon Olds Stag’s Leap Jonathan

Cape

Jacob Polley The Havocs Picador

Deryn Rees-Jones Burying the Wren Seren

Chair Carol Ann Duffy said:

‘In a year which saw a record number of submissions, my fellow judges and I are delighted with a shortlist which sparkles with energy, passion and freshness and which demonstrates the range and variety of poetry being published in the UK.’

Poets’ biographies

Simon Armitage

Simon Armitage was born in 1963 and lives in West Yorkshire. He has published nine volumes of poetry, including The Universal Home Doctor and Travelling Songs, both published by Faber in 2002. He has received numerous awards for his poetry including the Sunday Times Author of the Year, one of the first Forward Prizes and a Lannan Award. His bestselling and critically acclaimed translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Faber) was published in 2007. In 2010 Armitage was awarded the CBE for services to poetry. His last collection, Seeing Stars (Faber), was shortlisted for the 2010 T S Eliot Prize.

Sean Borodale

Sean Borodale works as a poet and artist, making scriptive and documentary poems written on location; this derives from his process of writing and walking for works such as Notes for an Atlas (Isinglass, 2003) and Walking to Paradise (1999). He has recently been selected as a Granta New Poet, and Bee Journal is his first collection of poetry. He lives in Somerset

.

Gillian Clarke

Gillian Clarke was born in

Cardiff

, and now lives with her family on a smallholding in Ceredigion. Her collections of poetry include Letter From a Far Country (1982); Letting in the Rumour (1989); The King of Britain's Daughter (1993); and Five Fields (1998). The latter three collections were all Poetry Book Society Recommendations. She has also written for stage, television and radio, several radio plays and poems being broadcast by the BBC. Gillian Clarke's most recent poetry collection is A Recipe for Water (2009). In 2008 she published a book of prose, including a journal of the writer's year, entitled At The Source, and was named as Wales' National Poet. In 2010 she was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry.

Julia Copus

Julia Copus was born in

London

in 1969. The World’s Two Smallest |Humans and her two previous collections, The Shuttered Eye and In Defence of Adultery, were all Poetry Book Society Recommendations. She has won First Prize in the National Poetry Competition and the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem. A radio version of the sequence ‘Ghost’ was shortlisted for the 2011 Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry. She works as an Advisory Fellow for the Royal Literary Fund.

Paul Farley

Paul Farley was born in Liverpool in 1965. He won the Arvon Poetry Competition in 1996 and his first collection of poetry, The Boy from the Chemist is Here to See You (1998), won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. The Ice Age (2002) was shortlisted for the T S Eliot Prize and won the Whitbread Poetry Award in 2003. In 2004, he was named as one of the Poetry Book Society’s ‘Next Generation’ poets. Further collections are Tramp in Flames (2006) and The Atlantic Tunnel: Selected Poems (2010). He currently lectures in Creative Writing at the University

of Lancaster

. He also writes radio drama, and several plays have been broadcast on BBC Radio. Field Recordings: BBC Poems 1998-2008 (2009) was shortlisted for the 2010 Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry. His book of non-fiction, Edgelands: Journeys into England’s Last Wilderness (2010), written with Michael Symmons Roberts, won the 2009 Jerwood Prize for Non-Fiction.

Jorie Graham

Jorie Graham was born in

New York City

in 1950 and raised in Rome

. She has published nine collections of poetry in the UK with Carcanet, most recently Sea Change (2008), Never (2002), Swarm (2000), and The Dream of the Unified Field: Selected Poems 1974-1994, which won the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She has taught at the University

of Iowa Writers

' Workshop and is currently the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard

University

. She served as a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets from 1997 to 2003.

Kathleen Jamie

Kathleen Jamie was born in Scotland in 1962. She has published several collections of poetry, including: Black Spiders (1982), The Way We Live (1987), The Queen of Sheba (1994), Jizzen (1999), and her selected poems, Mr & Mrs Scotland Are Dead, was published in 2002. Her poetry collection, The Tree House (2004), won the 2004 Forward Prize (Best Collection), and was a PBS Choice. A travel book about Northern Pakistan, The Golden Peak (1993), was recently updated and reissued as Among Muslims: Meetings at the Frontiers of Pakistan (2002). She lives in Fife, is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and in 2010 was appointed Chair of Creative Writing at Stirling

University

.

Sharon Olds

Sharon Olds was born in 1942 in

San Francisco

. Her first collection of poems, Satan Says (1980), received the inaugural San Francisco Poetry Center Award. The Dead & the Living (1983) received the Lamont Poetry Selection in 1983 and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her other collections include Strike Sparks: Selected Poems (2004) and The Father (1992), which was shortlisted for the T S Eliot Prize. Her last collection, One Secret Thing ( Jonathan

Cape

, 2009) explored the themes of war, family relationships and the death of her mother, and was also shortlisted for the T S Eliot Prize. She currently teaches creative writing at New York

University

.

Jacob Polley

Jacob Polley was born in Carlisle in 1975. Picador published his first book of poetry, The Brink, in 2003 and his second, Little Gods, in 2006. His first novel with Picador, Talk of the Town, came out in 2009 and won the 2010 Somerset Maugham Award. Jacob was selected as one of the Next Generation of British poets in 2004. In 2002 he won an Eric Gregory Award and the Radio 4/Arts Council ‘First Verse’ Award. Jacob was the Visiting Fellow Commoner in Creative Arts at Trinity

College

, Cambridge

, 2005-07, and Arts Queensland’s Poet in Residence in 2011.

Deryn Rees-Jones

Deryn Rees-Jones was born in Liverpool in 1968 and was educated at the

University

of Wales

, Bangor

, and Birkbeck

College

, London

. She is an Eric Gregory Award winner, and her collection The Memory Tray (Seren, 1994) was shortlisted for a Forward Poetry Prize for Best First Collection. Her other collections of poetry are Signs Round a Dead Body (Seren, 1998), Quiver (Seren, 2004) and Falls & Finds (Shoestring, 2008). She was selected as one of the Poetry Book Society’s ‘Next Generation Poets’ in 2004. Her critical work includes a monograph on Carol Ann Duffy, and the book of essays Consorting with Angels which accompanies Modern Women Poets (Bloodaxe, 2005). She lives in Liverpool.

October 8, 2012

Harry Mathews' "Septina" by David Morley

Fascinating post by JoAnne Simpson Growney, a poet and mathematician, from her blog. She writes:

Can sestina-like patterns be extended to other numbers? Poet and mathematician Jacques Roubaud of the OULIPO investigated this question and he considered, in particular, the problem of how to deal with the number 7 of end-words - for 7 does not lead to a sestina-like permutation. Rombaud circumvented the difficulty (see Oulipo Compendium -- Atlas Press, 2005) by using seven 6-line stanzas, with end-words following these arrangements:

123456 715243 674125 362714

531672 457361 246537

In ‘Safety in Numbers’, Oulipian Harry Mathews has followed Roubaud's specifications - and Mathews' septina also uses the words one, two, three, . . ., seven as end-words.

Safety in Numbers by Harry Mathews

The enthusiasm with which I repeatedly declare you my one

And only confirms the fact that we are indeed two,

Not one: nor can anything we do ever let us feel three

(And this is no lisp-like alteration: it’s four

That’s a crowd, not a trinity), and our five

Fingers and toes multiplied leave us at six-

es and sevens where oneness is concerned, although seven

Might help if one was cabalistically inclined, and “one”

Sometimes is. But this “one” hardly means one, it means five

Million and supplies not even an illusion of relevance to us two

And our problems. Our parents, who obviously number four,

Made us, who are two; but who can subtract us from some

mythical three

To leave us as a unity? If only sex were in fact “six”

(Another illusion!) instead of a sly invention of the seven

Dwarves, we two could divide it, have our three and, just as four

Became two, ourselves be reduced to one

– Actually without using our three at all, although getting two

By subtraction seems less dangerous than by division and would also

make five

Available in case we ever decided to try a three-

some. By the way, this afternoon while buying a six-

pack at the Price Chopper as well as a thing or two

For breakfast, I noticed an attractive girl sucking Seven-

Up through an angled and accordioned straw from one

Of those green aluminum containers that will soon litter the four

Corners of the visible world – anyway, this was at five

O’clock, I struck up a conversation with a view to that three-

some, don’t be shocked, it’s you I love, and one

Way I can prove it is by having you experience the six

Simultaneous delights that require at the very least seven

Sets of hands, mouths, etcetera, anyway more than we two

Can manage alone, and believe me, of the three or four

Women that ever appealed to both of us, I’d bet five

To one this little redhead is likeliest to put you in seven-

th heaven. So I said we’d call tomorrow between three

And four p.m., her number is six three nine oh nine three six.

I think you should call. What do you mean, no? Look, if we can’t

be one

By ourselves, I’ve thought about it and there aren’t two

Solutions: we need a third party to . . . No, I’m not a four-

flusher, I’m not suggesting we jump into bed with six

Strangers, only that just as two plus three makes five,

Our oneness is what will result by subtracting our two from three.

Only through multiplicity can unity be found. Remember “We Are

Seven”?

Look, you are the one. All I want is for the two

Of us to be happy as the three little pigs, through the four

Seasons, the five ages, the six senses, and of the heavenly spheres

all seven.

Mathews' poem is found - along with 150 other maths-related poems - in the anthology Strange Attractors: Poems of Love and Mathematics (A K Peters, 2008), collected and edited by Sarah Glaz and JoAnne Simpson Growney.

September 29, 2012

September 28, 2012

A Farewell to English by David Morley

This road is not new.

I am not a maker of new things.

I cannot hew

out of the vacuumcleaner minds

the sense of serving dead kings.

I am nothing new

I am not a lonely mouth

trying to chew

a niche for culture

in the clergy-cluttered south.

But I will not see

great men go down

who walked in rags

from town to town

finding English a necessary sin

the perfect language to sell pigs in.

I have made my choice

and leave with little weeping:

I have come with meagre voice

to court the language of my people.

from 'A Farewell to English' Part Seven by Michael Hartnett

'Song' by David Morley

Insects never learn about glass.

No more can I see through your absence.

Any stone flung in a river

Shatters the moon's reflection.

May we be reunited.

John Riley, 'Song'.

September 23, 2012

The Crowd by David Morley

And today, as you walk to the match, I am beside you.

Proud to be alive. Proud to be walking beside you,

to take our seats together.

And you know my name. You know all our names.

We are beside and between you,

our souls, invisibly visible.

We are waking. We are smiling.

We are walking in your hearts.

And we are prouder still to know today,

tomorrow, next week, month or year

you will not chant us down again.

You will not chant us down in our sorrows.

You will not chant us back into the earth.

For we left the earth where we thought we were alone

yet we are beside you, laughing and singing and unbroken.

If you were to hear me among the crowd

you would hear a song.

Were I to pass invisibly among your jostling arms,

or carried to earth, you would hear me singing with you.

If I took you to one side and told you 'you were my brother',

what would you sing to your brother?

If I took you to one side and told you 'you were my sister',

what would you sing to your sister?.

You are my brother and you are my sister.

Nothing can kill me, for I am the crowd.

And the sun shone over Merseyside, over Manchester,

over the Pennines with its skylarks and brightening becks,

over Penistone and Stocksbridge and Hillsborough.

Liverpool fans in their buses - cheering the roof off -

anticipation, faith in the day and the song of life

no stronger than your own, just scousier.

You will not chant them down again.

You will not chant them down in their sorrows.

You will not chant them back into the earth.

And today, as you walk to the match, they are beside you.

Proud to be walking beside you, to take your seats together.

And you know their names. You know all their names.

We are walking to the same match.

We are walking on the same road.

We are arriving at the same gates.

We are waiting. We are laughing. We are singing.

And we do not know it but this is joy.

Nothing can kill us, for we are the crowd.

September 13, 2012

The day after the Hillsborough Disaster by David Morley

Writing about web page http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-19586393

As a lifelong Liverpool FC supporter I am heartened but not surprised by what happened in Parliament yesterday & in the media today.

On the day of the Hillsborough disaster I watched Liverpool supporters arrive in their coaches as they came through Deepcar. They were happy, excited, sober. The sun shone. I waved, cheered.

An hour later, an old man staggered from his terrace house. The sound of the match on the radio through his open door.

‘Something terrible is happening’, he said. He held my arm: ‘It is terrible and nobody is doing anything’.

Next morning I drove through Hillsborough to Sheffield. Graffiti everywhere. Huge letters: ‘HILLSBOROUGH. SOUTH YORKSHIRE POLICE NOT TO BLAME’.

I stopped my car in disbelief. Who else but the police could have carried out such an act and got away with it?

The point is: the day after the Hillsborough disaster we all of us knew what the truth was.

September 1, 2012

Vernon Watkins by David Morley

Heatherslade Residential Home 1, West Cliff, Southgate, Swansea, West Glamorgan SA3 2AN

[image error] [image error]

Poet. He was born in Maesteg, Glam., but the frequent postings of his father, who was a bank manager, took the family to live at Bridgend and Llanelli before they settled, in 1913, in Swansea. Ten years later they moved out to Redcliffe, Caswell Bay and finally, in 1931, on his father's retirement, to Heatherslade on Pennard Cliffs. It was the shoreline of Gower, which he knew as a resident from the age of seventeen and had often visited previously, which was to provide the illustrative material of Vernon Watkins's poetry, the more nostalgically because, after a year at Swansea Grammar School, he was despatched first to Tyttenhanger Lodge, Seaford, Sussex, and then to Repton School in Derbyshire. Both his parents were Welsh-speaking but Vernon, a victim of that contemporary parental belief that it was necessary to escape from the parochiality of Wales, never spoke or learned the language. The only Welsh source he was able later to use in his poetry was the story of Taliesin, of which his beloved Gower provided a variant.

At Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he read French and German, he found the course's emphasis on criticism to be uncongenial and, despite satisfactory examination results at the end of his first year, decided to abandon Cambridge and tried to persuade his father to allow him to travel to Italy in order to acquire experience for the poetry to which he was already committed. His father's response was unsympathetic; in the autumn of 1925 Vernon Watkins became a junior clerk in the Butetown branch of Lloyds Bank in Cardiff. Associating poetry with the idyllic experience of his last eighteen months at Repton - retrospectively a golden and heroic society - and desperate at both the need to grow up and the glum reality of a working life, he suffered a nervous breakdown which necessitated his removal, after six months' absence, to the branch of Lloyds Bank at St. Helen's, Swansea, so that he could live and be cared for at home. He remained in that employment, except for military service during the Second World War, until his retirement and he lived the rest of his life at Pennard. He always spoke of his nervous breakdown as a 'revolution of sensibility': his poetry, when it came, was to be devoted to 'the conquest of time', by which he meant, at first, the immortalization of the Eden-like memories of youth and the validation of all that he had known and loved. The 'grief' he felt was the genesis of all that followed. Gradually the paganism of the Romantic poets who had nourished him (despite the Christian background of his home) gave way to Neoplatonism (with the idea of the replica and the moment which is all moments) and that to a more Christian, if always unorthodox, view of life. The defeat of time was integral, in his view, to the function of the poet.

His first volume of poetry, Ballad of the Mari Lwyd (1941), appeared after he had left the bombed town of Swansea for service in the RAF Police: the title-poem is a striking adaptation of the familiar Welsh folk-ceremony to the validation of the dead. The Lamp and the Veil (1945) consists of three long poems (one to his sister Dorothy) and was succeeded by Selected Poems (1948), The North Sea (translations from Heine, 1951) and two collections which are his most successful, The Lady with the Unicorn (1948) and The Death Bell (1954), the title-poem of which commemorates his father. He also published Cypress and Acacia (1959) and Affinities (1962); Fidelities (1968) appeared posthumously, although the selection was made by the poet himself.

Although a meticulous craftsman and as much a master of poetic form as Dylan Thomas, by whom he was for long overshadowed, Vernon Watkins became nevertheless a very different kind of poet - a modern metaphysical, whose insight-symbols from the Gower shoreline carried his 'grief' towards an immortality which, in Christianizing itself, gradually calmed the original impetus. His later poetry maintained its formal excellence but the weakening of the emotional impulse, a tendency to short-cut the metaphysical argument and an increasing emphasis on the centrality of the poet's role make it both less accessible and less attractive. Much of his best work is a response to three traumatic experiences: his nervous breakdown, the destruction of old Swansea during the blitz, and the death of Dylan Thomas. His overall achievement throughout a lifetime of 'toil' makes him one of the greatest of Welsh poets in English as well as one of the most unusual. At the time of his death in Seattle, during a second visit as Professor of Poetry at the University of Washington, his name was being canvassed, with others, for the Poet Laureateship. After his death, Uncollected Poems (1969), Selected Verse Translations (1977), The Breaking of the Wave (1979) and The Ballad of the Outer Dark (1979) were all put together from a mass of unpublished material, while I That Was Born in Wales (1976) and Unity of the Stream (1978) were selections made from his published works. The Collected Poems were published in 1986.

(Information taken from Meic Stephens’ New Companion to the Literature of Wales, University of Wales Press, 1998)

August 11, 2012

The Site by David Morley

after Mandelshtam

Why am I trailing you,

now through a pine-wood, now

through the words I write,

going nowhere fast?

There’s a gypsy encampment on the steppes,

newly moved in—sharp fires gone

by morning; the stamped ash

surrenders no clue or forwarding address.

I am in the pinewoods, trailing you.

There you were, like memory, a shackle.

Cling to me, you said.

Voronezh, January 1937

David Morley's Blog

- David Morley's profile

- 13 followers