David Morley's Blog, page 19

June 13, 2016

The Invisible Gift, a Selected Poems by David Morley

Sarah Hymas reviews “The Invisible Gift: Selected Poems” in The Compass

There is something overwhelming about years’ worth of work bound into one book: the chatter of all those poems, all those preoccupations and the slow growth of the poet being compressed into something dangerously close to white noise. I share the reservations expressed by Jane Routh in Issue 1 of The Compass around the concept of a Selected.

poems, all those preoccupations and the slow growth of the poet being compressed into something dangerously close to white noise. I share the reservations expressed by Jane Routh in Issue 1 of The Compass around the concept of a Selected.

This is not, however, true for David Morley’s ‘The Invisible Gift’. Morley’s focus, while elastic, comes back again and again to a tight realm: the natural world, folklore, traveller and domestic scenes. This allows the poems to layer up and build a deep resonant world and the book to open, as if it is a door, shedding light onto what is as familiar and unknown as my neighbour’s house.

The poems are taken from his four Carcanet collections, Scientific Papers (2002), Invisible Kings (2007), Enchantment (2010) and The Gypsy and the Poet (2013), covering just over ten years, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that this Selected has such cohesion. The book is sectioned, gathering poems from each collection into constituent parcels, but apart from The Gypsy and the Poet, neither books nor dates are referenced in the contents or section titles. This encourages the flow in presentation and reading of the work.

There is also a prologue and an epilogue (both taken from Enchantment). The first is ‘Hedgehurst’ which I read as a manifesto, of a kind, for the book. The latter ‘Spinning’ is a reflection on the power and fabulous nature of storytelling, a summing up, I suppose, although that does not give the poem its full due. I like how it is separate from the body of the Selected, how this gives it space and an identity that may have been lost if it were alongside companion pieces from the original book.

So, as manifesto:

I called

my name into the night. The trees

shushed me, then answered

with caterpillars baited on threads.

I called again. Moths moored

in bark-fissures flickered out,

fluttered towards me as I spoke

Naming and connecting is one of the spines of the collection as a whole: how definition brings us closer to the world we occupy. The importance of language is its ability to shape and open our understanding. This notion is explored further in a poem like ‘Kings’ where English and Romany interweave throughout the poem. There is a slight layout issue which means translations of the Romany (in footnotes) do not always sit on the same pages as the original word. I gave up flipping pages and simply read the Romany as sounds within the English ‘sense’ which was a far more satisfactory reading. That way the poem occupied itself in me as an aural, physical entity rather than the intellectual relating of a distant event.

‘Hedgehurst’ is introduced as a character from Fireside Tales of the Traveller Children. As such it makes issues of violence seem safe by setting them in this fabulous context: ‘My father flared and fumed as / I fumbled with gravities’. These issues of violence are echoed in a more familiar setting in a later poem, ‘Three’ set in kitchen and bedrooms, where another father ‘has a fist crammed with kitchen knives’ and ‘One of us is guilty of the crime of two biscuits.’ And here they hold a direct potency and pain, stripped bare in the stark electric light of the home.

But, thankfully, there is the redemptive power of love. Back to ‘Hedgehurst’: ‘I whispered my wife’s name …’

I called her again.

Moths stirred in bark-fissures.

They flickered out, flutter

towards us as I spoke her name,

as though my voice was a light.

This love is not confined to humans, as displayed in the consecutive poems ‘Osip Mandelshtam on the Nature of Ice’ and ‘Two Temperatures for Snow’. The delicate force that binds both narrators to the paradoxical abundant temporality of ice and snow is likened to a ‘force-field’, yet exposing and liberating. Such is the concentration of connection to other, the desire to understand and the rewards that come from this. Then there is the playfulness of ‘Chorus’ where the dawn chorus and birds’ activities are seen in the light of new beginnings, in this case the birth of a son.

The rook roots into roadkill for the heart and the hardware.

The tawny owl wakes us to our widowhood. The dawn is the chorus.

The repetitious litany of this poem is hypnotic, delicious, soporific. It’s probably no coincidence that images of repetition, of circular motion and circles, are found throughout the book, from creatures making circles to blacksmiths’ iron circles and the circle of the circus.

‘A Lit Circle’ is a short sequence detailing circus performers: ‘Rom the Ringmaster’, ‘Demelza Do-it-All’, ‘Kasheskoro the Carpenter’ and other high energy, breathless characters describing their skills, relationships and the prejudices against them, the factions and ‘Round it goes, this hate, hurtling around, / The question is where’s that hate going to hurtle when it’s without home,’. Coming as this sequence does after another sequence, about Papusza, Romany name for the poet Bronis ława Wajs, traveller and performer who suffered terrible injustice and persecution through her life, preempts the epilogue’s declaration of the importance of creative expression in people’s spiritual strength and salvation.

The sonnet sequence from The Gypsy and the Poet explores how this creative expression may come about. Again there is a connection with nature, a listening that enables the entrance to a deeper understanding. Where at first, the gypsy Wisdom Smith

… leans against an ash tree, shouldering his violin,

slipping the bow to stroke the strings that stay silent

at distance. All John Clare hears is a heron’s cranking

Wisdom watches the poet’s continued writing, frustration and ‘scribbling pen’ and draws him to his world of tobacco and music, his way of seeing what is ‘Deepest of the Deep’ what is surface, what is love and who and what he is writing for. It is an almost comic sequence, playing formality off instinct, class and society off natural law that ultimately presses its beliefs and ethics into and between lines. ‘I call out to my child, and he is everywhere, and she is everyone.’

The Invisible Gift is a fitting testament to a poet whose work over the last decade or so shows a tracing of origins and deep connections.

June 12, 2016

John Clare's Heirs by David Morley

‘John Clare’s Heirs’ by Stephen Burt from “The Boston Review”

Probably nobody wishes they had been John Clare. The son of an agricultural laborer and  an illiterate mother in tiny Helpston, Northamptonshire, Clare (1793–1864) had only the barest schooling. After finding, at age thirteen, “a fragment” of James Thomson’s long poem The Seasons (1730), Clare “scribbled on unceasing,” drafting his own poems in fields and ditches. Helped by a vogue for peasant poets, his Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery (1820) likely sold more than 3,000 copies in a year. Visits to London literati, and three more books, ensued, despite diminishing sales. In 1832 Clare, his wife, and their six children left Helpston for another village, a few miles off, where he never felt at home. Five years later Clare was declared insane and confined to an asylum. In 1841 he escaped and walked home, sleeping under culverts and trudging twenty miles a day. Clare spent the rest of his life in another asylum, “disowned by my friends and even forgot by enemies,” though in some years he continued to write. At times he thought he was Lord Byron. His late poems can present a scary sense of disembodied, empty confusion.

an illiterate mother in tiny Helpston, Northamptonshire, Clare (1793–1864) had only the barest schooling. After finding, at age thirteen, “a fragment” of James Thomson’s long poem The Seasons (1730), Clare “scribbled on unceasing,” drafting his own poems in fields and ditches. Helped by a vogue for peasant poets, his Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery (1820) likely sold more than 3,000 copies in a year. Visits to London literati, and three more books, ensued, despite diminishing sales. In 1832 Clare, his wife, and their six children left Helpston for another village, a few miles off, where he never felt at home. Five years later Clare was declared insane and confined to an asylum. In 1841 he escaped and walked home, sleeping under culverts and trudging twenty miles a day. Clare spent the rest of his life in another asylum, “disowned by my friends and even forgot by enemies,” though in some years he continued to write. At times he thought he was Lord Byron. His late poems can present a scary sense of disembodied, empty confusion.

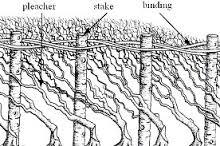

And yet most of Clare’s voluminous poetry, early and late, mad and sane, exults in what he saw firsthand outdoors: crops, wildflowers, birds, mammals, and fellow laborers, all threatened by the Enclosure Acts of the early 1800s, which turned shared fields and forests into private property. Before enclosure, Clare wrote in the manuscript version of “October” (1827),

Autum met plains that stretched them far away

In uncheckt shadows of green brown & grey

Unbounded freedom ruld the wandering scene

No fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect from the gazing eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky

(Note the misspellings, which his printed books correct; some modern editors, led by Eric Robinson, restore the manuscript usage.) The wonder that Clare found in unspoiled, unenclosed landscapes was something like the wonder he found in childhood, with an unphilosophical glow:

We sought for nuts in secret nook

We thought none else could find

And listened to the laughing brook

And mocked the singing wind;

We gathered acorns ripe and brown

That hung too high to pull,

Which friendly windows would shake a-down

Till all had pockets full.

He also portrayed the gypsies, now called Roma, as “a quiet, pilfering, unprotected race” whose language he claimed he could speak. Almost everything that could have seemed, to a nineteenth-century reader, like a reason to count Clare as minor, or not to read him, makes him a resource for poets today. “Bard of the fallow field / And the green meadow,” as he called himself, Clare remained closely attentive to what we now call his environment, what he called “nature,” in a way that is neither touristic nor ignorant of agricultural effort. He saw tragic ironies all over the place, but he never sought verbal ironies himself: he is about as sincere (if not naive) as poets get. Clare seems to have benefited from few of the changes wreaked on the planet since the invention of the steam engine and cannot be blamed for whatever brought them about: he may be the last significant white Anglophone poet for whom that was true.

Better yet, Clare’s apparently unorganized—but minutely observed—poetry looks like a model for poets who want to stay true to a material world while rejecting the hypotactic, well-made structures that earlier generations preferred. Clare’s poems, Stephanie Weiner writes in her study of his legacy, “insist on their origin in real acts of perception” even though “he seems deliberately to court unboundedness.” John Ashbery loves him: in his 1969 prose poem “For John Clare,” “There is so much to be seen everywhere that it’s like not getting used to it, only there is so much it never feels new.” Twenty years later, Ashbery called Clare’s verse “a distillation of the natural world with all its beauty and pointlessness, its salient and boring features preserved intact.” The distinguished scholar Angus Fletcher found in the incontrovertibly English Clare—and in Ashbery and Walt Whitman—what Fletcher called A New Theory for American Poetry (2004), all about the anti-hierarchical, centerless, “self-organizing and nonlinear . . . . environment-poem.”

No wonder some poets now work with Clare in mind. The sonnets of The Gypsy and the Poet (2013), by the English writer David Morley, dramatize Clare’s meetings with the Romany leader Wisdom Smith:

Clare gazes at the fire. Wisdom cradles the poet’s cup and stirs

and stares at the tea leaves: ‘Our lives are whin upon this heath

whose growing makes one half of heaven and one half earth.

You desire an earthly heaven, John, and will find it in Helpston.

The leaves also say you are welcome to my fire—and to this cup.’

‘You read a world from so little,’ thinks Clare. And the Gypsy looks up.

…Morley weaves Romany lore and language (often untranslated) into his poems; a trained biologist, he also corrals the horticultural details. Morley’s wise, witty, circuitous Gypsies seem better adapted to the land than Clare himself, though his written words may outlast their music and speech: “Wisdom Smith tugs corks on two bottles. He pulls a long face. / ‘John, I know no man more half-in or half-out of your race. . . . / We die if we do not move, whereas John—John, you would die.” In their low-pressure conversation, their unobtrusive hexameters, their samples of English and Roma customs and landscape, Morley’s poems draw winningly on aspects of Clare that no American poet could use...

June 11, 2016

The Dynamics of Birdsong by David Morley

Ken Head reviews ‘The Gypsy and the Poet’ for “Ink, Sweat and Tears”

The strands of David Morley’s thought in this collection are rich and various.  On the one hand, he makes use of ... his knowledge of the Romani dialect in which he sometimes writes. On the other, the poems in the book’s first and third sections work to develop an insight into the real-life friendship between John Clare, the poet, and Wisdom Smith, the gypsy, material for which Morley draws from Clare’s journals and emphasises in the title of the opening sonnet, “Wisdom Smith Pitches his Bender on Emmonsales Heath, 1819″. The central section of the book, by contrast, is concerned to demonstrate the validity of Clare’s own belief in the creative forms of nature itself: “I found the poems in the fields/ And only wrote them down.” There is concrete poetry here and experiments in what George Szirtes has described as “the dynamics of birdsong”. These elements constitute a complex mix, the source material for which, it’s probably fair to say, is not well known, a particular difficulty, I felt, with the epigraphs taken from traditional Traveller songs and The Book of Wisdom of the Egyptians, for which no translation is offered because, as the notes make clear, “meaning may be found within the poems.” True enough. Both in content and form, the poems work hard to be accessible, but even given the problems of translation, I should have preferred to make my own judgement as to the relationship between each epigraph and the content of the poem related to it.

On the one hand, he makes use of ... his knowledge of the Romani dialect in which he sometimes writes. On the other, the poems in the book’s first and third sections work to develop an insight into the real-life friendship between John Clare, the poet, and Wisdom Smith, the gypsy, material for which Morley draws from Clare’s journals and emphasises in the title of the opening sonnet, “Wisdom Smith Pitches his Bender on Emmonsales Heath, 1819″. The central section of the book, by contrast, is concerned to demonstrate the validity of Clare’s own belief in the creative forms of nature itself: “I found the poems in the fields/ And only wrote them down.” There is concrete poetry here and experiments in what George Szirtes has described as “the dynamics of birdsong”. These elements constitute a complex mix, the source material for which, it’s probably fair to say, is not well known, a particular difficulty, I felt, with the epigraphs taken from traditional Traveller songs and The Book of Wisdom of the Egyptians, for which no translation is offered because, as the notes make clear, “meaning may be found within the poems.” True enough. Both in content and form, the poems work hard to be accessible, but even given the problems of translation, I should have preferred to make my own judgement as to the relationship between each epigraph and the content of the poem related to it.

The collection, sixty-four poems in all, is bookended with two italicised sonnets which seem to me to define the basis of the entire project. In the first, “The Invisible Gift”, Morley describes the way in which, he believes, Clare went about making poems: “John Clare weaves English words into a nest/ and in the cup he stipples rhyme, like mud/ to clutch the shape of something he can hold/ but not yet hear; and in the hollow of his hearing,/ he feathers a space with a down of verbs/ and nouns heads-up.” It is a joyous creative process, craftsmanlike and unpretentious, that is being described, although at the other end of the collection, “The Gypsy and the Poet” makes clear the agonies a compulsion to write may bring with it: “Shades shift around me, warming their hands at my hearth./ It has rained speech-marks down the windows’ pages,/ gathering a broken language in pools on their ledges/ before letting it slither into the hollows of the earth.” Morley may, perhaps, be speaking of his sense of his own predicament here, caught between cultures, struggling with the notion of belonging, although what he writes is clearly, he believes, also true for Clare. The point, well made throughout the Wisdom Smith sonnets, is especially clear in “An Olive-Green Coat”: “John Clare longs to look the part, the part a poet can play/ – no part labourer. He stares at a tailor’s display, his money/ gone, his hands numb with the vision of further toils.”

Clare’s struggles with poverty, lack of education, his sense of isolation, the misery and depression these forced him to live with and his eventual decline into mental illness, are well documented and commemorated poignantly in what may be, if not his best, then certainly his best known, most anthologized poem, “I am”: “I am – yet what I am, none cares or knows;/ My friends forsake me like a memory lost:/ I am the self-consumer of my woes -”. Morley’s poems, however, in bringing together the very different mindsets of poet and gypsy, both of them, in material terms, impoverished, both living close to wild nature, but in other ways so dissimilar, create a dynamic that also highlights the love of nature, the life and energy, which readers familiar with Clare’s work will know predominate throughout his writing. “Mad” makes the point well: “Wisdom Smith smiles into his steaming bowl: ‘March Hares/ grow spooked in their bouts, so tranced by their boxing,/ you can pluck them into a sack by the wands of their ears!’/ John Clare hungers. He hugs his bowl and starts writing/ on the surface of the stew with a spoon. ‘Let the hare cool/ on the night wind,’ urges the Gypsy. ‘Sip him but do not speak.’ ”

In what Wisdom Smith teaches, or tries to teach, Clare, there is Romani lore that has been passed down through generations: how to survive in a world that is always indifferent and may well be hostile, how to enjoy it nonetheless, how to learn who and what are trustworthy and who and what may not be. As Smith says in “A Walk”, ” ‘I know no more than a child, John,/ but I know what to know …’ “ There are many similar examples, moments when the practical gypsy spells out the lessons of life to the brooding, insecure poet: ” ‘I envy your free-roving,’ John Clare sighs to Wisdom Smith./ ‘To have the wide world as road and the sky and stars as your roof.’/ ‘That bread in your mouth, brother,’ butts in the Gypsy, ‘is ours/ because I bought it with my muscles and my calluses this morning./ Man, the day gads off to market with the dawn and everything/ sells itself under the sun: woods, trees, wildflowers and men.’ ”

This book, to which my one thousand words haven’t begun to do justice, is the most interesting new poetry I’ve read this year; it’s a delight, a testament to what is important, not only in English poetry, but in life also: ” ‘Poor John,’ whispers the Gypsy, ‘a quaking thistle would/ make you swoon.’ ‘Truth is, Wisdom, a thistle still could!’/ laughs the poet. And the friends snort and drink to the night./ Clare snores beneath his blanket. Wisdom rises from the earth./ Their fire is all there is to show. Orion stares down on the heath./ He searches for their world with a slow sword of light.”

June 10, 2016

Everything is Poetry by David Morley

Review of "The Gypsy and the Poet"

Review of "The Gypsy and the Poet" by Stone and Star

David Morley's most recent collection, The Gypsy and the Poet… is a unique tribute to one of the most celebrated poets of the English countryside, John Clare. Many of the poems make up an ongoing dialogue between Clare and a mysterious Gypsy named Wisdom Smith.

Wisdom Smith appears briefly in John Clare's notebooks, and Morley uses this as a starting point for a series of playful, joyous sonnets made up of springy, alliterative verse which occasionally turns sombre (as when Clare says "Were poems children/I should stamp their lives out" and Wisdom Smith responds "Then do not make them", in 'My Children'.) I found myself wondering if Wisdom Smith was simply another aspect of Clare's complex personality (or is Clare another aspect of Wisdom Smith?) and if the sequence was a sort of Yeatsian dialogue of self and soul. This is particularly the case towards the end of the collection, as Clare descends into madness and the corporeal reality of the two figures' encounters becomes more doubtful. I think the poems can be read either as real encounters or as aspects of one personality, but in any case, the two characters have much to teach each other. Each sees the world at an angle that the other finds challenging, and so they bring each other to new understandings, even if it's through banter and mockery:

'I do not read, brother,' states Wisdom smiling,

'for I will not bother with Mystery.

Worlds move underfoot. Where lives Poetry?'

(from 'Worlds')

Wisdom Smith gets Clare to live in the moment, in the natural world; Clare gets him to look more seriously at poetry.

'Poetry is in season,' laughs John. 'Rooms woven from wound wood

are like rooms of woven words.' Wisdom looks at Clare - hard.

'Poetry is not everything. You know that, John,' smiles the Gypsy.

'You are wrong,' dances Clare. 'Everything. Everything is poetry.'

(from 'Bender')

The poems are highlighted by English and Romany epigraphs, which heighten the impression of a dialogue between two cultures, both at home in the natural world, but in different ways.

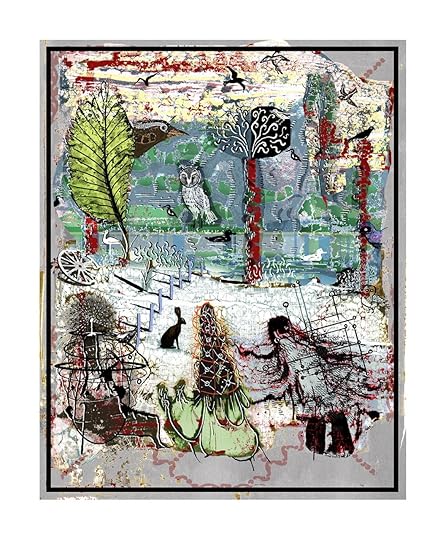

The book is divided into three sections, the first and third of which are the John Clare and Wisdom Smith sonnets. The central section is made up of a variety of nature poems, including pieces which became part of the Slow Art Trail in Strid Wood, poems based on birdsong and painted on bird boxes, and shape poems. I am not really a fan of shape poems in general, but I saw all the poems in this section as a kind of extension of John Clare's (and David Morley's) notebooks and his observations about his life in the natural world. These poems are a record of what is happening around us, often unperceived, and they go a long way to show us how complex and intertwined the natural world is. Two poems, 'Fight' and 'Ballad of the Moon, Moon' are based on Lorca and his rich, strange perceptions of the Gypsy world.

The Gypsy and the Poet is a book to be taken out and read in the fields or the forest, but if this isn't possible, it can at least take the reader there in imagination and provide new insights into our relationship with the natural world and with other cultures, all wrapped up in some very colourful, distinctive and haunting verse.

BARDEN TOWER (David Morley)

I have heard a tourist claim this view

as though she had bought it at cost -

an expensive mirror. Unseen and ornately

ivy throws its ropes across the leaf-litter

shifting a forest's massive furniture;

the moss robes veil the thrones

of fallen oaks; trees flare with lichen;

Autumn smashes rainbows across

the woodland floor. You may never

have seen these trees more brilliantly

than when you turned your eyes

to that hunting lodge and sensed the light

kindle a million leaf mirrors.

In his woods near Lake Tuusula

Jean Sibelius shaped symphonies

from the speech of trees; firs bowed

violins while his swans sailed, keening.

Before his death a solitary swan

veered over and made him her own.

I am close to you who once shared this view.

This is not my sky, my flight, my words. This is not a mirror.

Poem © David Morley, 2013. Artwork © Peter Blegvad. Used by permission.

August 6, 2013

The Gypsy and the Poet by David Morley

John Clare, Wisdom Smith and Me

I’d finished a trilogy of books for Carcanet, and I had no idea what I was going to do next. What poet really does? I had been invited by New Networks for Nature, an alliance of creators whose work draws strongly on the natural environment, to perform at their annual gathering. My reading took place in Helpston Church. Afterwards, I sat down by John Clare’s grave and had a little chat with him.

Back home, I re-read Jonathan Bate’s biography then I read Clare’s Notebooks. Because Clare thinks nobody’s going to be reading them, he sounds more at ease with himself - a real, living voice surges through. He sows the earth for unwritten poems and even for an unpublished prose book about the natural history of Northamptonshire called Biographies of Birds and Flowers.

The Notebooks also show the presence of Gypsies in Clare’s life. I am partly Romani, I write in Romani dialect, and am alert to anything Gypsy. Clare liked Gypsies. He liked them at a time when it was acceptable for a clergyman to write in the local paper, “This atrosious tribe of wandering vagabonds ought to be made outlaws and exterminated from the earth”. Gypsies liked the poet back: ‘As soon as I got here the Smiths gang of gipseys came and encampd near the town and as I began to be a desent scraper we had a desent round of merriment for a fortnight’. A fortnight of merriment is not gained unless the Gypsies trusted this local poet - with his fiddle and pen – completely.

Clare also sought them out for stories, songs and tunes. And one character keeps cropping up in the Notebooks, a Gypsy called Wisdom Smith: ‘Finished planting my ariculas—went a botanising after ferns and orchises and caught a cold in the wet grass which has made me as bad as ever—got the tune of “highland Mary” from Wisdom Smith a gipsey and pricked another sweet tune without name as he fiddled it’. Wisdom was the catalyst. Next day, I went into my writing shed and found Wisdom Smith sitting in the chair, waiting for me, and I seemed to step into him, or he stepped into me. Some days I found John Clare waiting with his friend. This triple team could write a lot better than I could alone: they could turn sonnets and make them an outdoor form, an unenclosed space for singing the world into being. Clare’s example, with Wisdom Smith’s energy and – yes – his wisdom, forced me to make a step-change and write poems about the the life of love.

I allowed myself to be taken over and to trust in that transformation completely. Emmanual Levinas wrote how ‘I am most like myself when I am most like you’. It is true that once upon a time the action of writing used to take me over so completely it obliterated me. But, newly, sometimes painfully, I felt myself to be more myself than ever. Yet here I was, taken over by a gypsy and a poet. I felt as if I had lived three lifetimes, transcending the self and entering a near-constant state of negative capability that allowed me to escape the “literary” - and write from a wild love of the world and for life:

Worlds

It is pleasant as I have done today to stand

... and notice the objects around us

‘There is nothing in books on this’, cries Clare.

‘I do not read, brother’, states Wisdom smiling,

‘for I will not bother with Mystery.

Worlds move underfoot. Where lives Poetry?

Look’, hums Wisdom Smith, ‘in the inner domes

of ghost orchids - how the buzzing rhymers

read light with their tongues; or in this anthill -

nameless draughtsmen crafting low rooms, drawing

no fame - except the ravening yaffle,

or fledgy starlings bathing in their crawl.

I see these worlds - lit worlds. I live by them’.

The wood-ants sting. John Clare shifts foot to foot:

‘I did not know you gave me any thought’.

‘This? All this - is nothing, John’, laughs Wisdom.

February 12, 2013

The Far Field by Theodore Roethke by David Morley

I

I dream of journeys repeatedly:

Of flying like a bat deep into a narrowing tunnel

Of driving alone, without luggage, out a long peninsula,

The road lined with snow-laden second growth,

A fine dry snow ticking the windshield,

Alternate snow and sleet, no on-coming traffic,

And no lights behind, in the blurred side-mirror,

The road changing from glazed tarface to a rubble of stone,

Ending at last in a hopeless sand-rut,

Where the car stalls,

Churning in a snowdrift

Until the headlights darken.

II

At the field's end, in the corner missed by the mower,

Where the turf drops off into a grass-hidden culvert,

Haunt of the cat-bird, nesting-place of the field-mouse,

Not too far away from the ever-changing flower-dump,

Among the tin cans, tires, rusted pipes, broken machinery, --

One learned of the eternal;

And in the shrunken face of a dead rat, eaten by rain and ground-beetles

(I found in lying among the rubble of an old coal bin)

And the tom-cat, caught near the pheasant-run,

Its entrails strewn over the half-grown flowers,

Blasted to death by the night watchman.

I suffered for young birds, for young rabbits caught in the mower,

My grief was not excessive.

For to come upon warblers in early May

Was to forget time and death:

How they filled the oriole's elm, a twittering restless cloud, all one morning,

And I watched and watched till my eyes blurred from the bird shapes, --

Cape May, Blackburnian, Cerulean, --

Moving, elusive as fish, fearless,

Hanging, bunched like young fruit, bending the end branches,

Still for a moment,

Then pitching away in half-flight,

Lighter than finches,

While the wrens bickered and sang in the half-green hedgerows,

And the flicker drummed from his dead tree in the chicken-yard.

-- Or to lie naked in sand,

In the silted shallows of a slow river,

Fingering a shell,

Thinking:

Once I was something like this, mindless,

Or perhaps with another mind, less peculiar;

Or to sink down to the hips in a mossy quagmire;

Or, with skinny knees, to sit astride a wet log,

Believing:

I'll return again,

As a snake or a raucous bird,

Or, with luck, as a lion.

I learned not to fear infinity,

The far field, the windy cliffs of forever,

The dying of time in the white light of tomorrow,

The wheel turning away from itself,

The sprawl of the wave,

The on-coming water.

II

The river turns on itself,

The tree retreats into its own shadow.

I feel a weightless change, a moving forward

As of water quickening before a narrowing channel

When banks converge, and the wide river whitens;

Or when two rivers combine, the blue glacial torrent

And the yellowish-green from the mountainy upland, --

At first a swift rippling between rocks,

Then a long running over flat stones

Before descending to the alluvial plane,

To the clay banks, and the wild grapes hanging from the elmtrees.

The slightly trembling water

Dropping a fine yellow silt where the sun stays;

And the crabs bask near the edge,

The weedy edge, alive with small snakes and bloodsuckers, --

I have come to a still, but not a deep center,

A point outside the glittering current;

My eyes stare at the bottom of a river,

At the irregular stones, iridescent sandgrains,

My mind moves in more than one place,

In a country half-land, half-water.

I am renewed by death, thought of my death,

The dry scent of a dying garden in September,

The wind fanning the ash of a low fire.

What I love is near at hand,

Always, in earth and air.

IV

The lost self changes,

Turning toward the sea,

A sea-shape turning around, --

An old man with his feet before the fire,

In robes of green, in garments of adieu.

A man faced with his own immensity

Wakes all the waves, all their loose wandering fire.

The murmur of the absolute, the why

Of being born falls on his naked ears.

His spirit moves like monumental wind

That gentles on a sunny blue plateau.

He is the end of things, the final man.

All finite things reveal infinitude:

The mountain with its singular bright shade

Like the blue shine on freshly frozen snow,

The after-light upon ice-burdened pines;

Odor of basswood on a mountain-slope,

A scent beloved of bees;

Silence of water above a sunken tree :

The pure serene of memory in one man, --

A ripple widening from a single stone

Winding around the waters of the world.

January 31, 2013

Almost Happiness by David Morley

Writing about web page http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/dec/14/customs-house-andrew-motion-review

A review of Andrew Motion, The Customs House, Faber and Faber, £12.99 Hb / £9.99 ebook, ISBN: 978-0-571-28810-6

Reading Andrew Motion’s lucid, brilliant, melancholic poetry collection The Customs House I was reminded of Edward Thomas’s moodily captivating essay ‘One Green Field’ in which Thomas realises how, ‘Happiness is not to be pursued, though pleasure may be; but I have long thought that I should recognize happiness could I ever achieve it... I never achieved it, and am fated to be almost happy in many different circumstances...’. The Customs House is a strong, searing and sad book. I think it is certainly his most achieved collection. It signals a central change to the way he is thinking and feeling in language. He is letting the world back into him. Not the public world and restive politics of the Laureateship, but a private world of understanding, humility and love. Andrew Motion is developing a late style that is far more open to possibility, one that is ‘almost happy in many different circumstances’:

The last colour to see when the sun goes down

will be blue, which now turns out to be not

only one colour but legion – as if I never knew.

from ‘Gospel Stories’

Edward Said believed the late style of creative artists ‘is what happens if art does not abdicate its rights in favour of reality’. I would argue (and I have heard the poet state as much) that Motion’s stint as Laureate pushed him to abdicate the rights of his poetry to the reality of that public responsibility. Writing of the final poems of Cavafy, Said commended ‘the artist’s mature subjectivity, stripped of hubris and pomposity, unashamed either of its fallibility or of the modest assurance it has gained as a result of age and exile’. The Customs House possesses and is possessed by a bare, pared-down tone stripped of hubris and unashamed of its fallibility. Andrew Motion has fully returned from the public exile of self-conscious art. He returns scorched but wiser. Like the poets of The English Line – Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas, Keith Douglas, Philip Larkin, Motion himself - the mature subjectivity of tone is of course a never-to-be-realised happiness, a restlessness of feeling, a scarred understanding that yields fine, heart-rending language and the grace and pressure of precise memory:

Now wind has died in the lime trees

I have forgotten what sense they made,

but not the leaf the wind dislodged

that fell between my shoulder blades.

‘Fall’

Motion’s poetry has always possessed an affecting tonal vulnerability. It is a quality that draws a reader closer - and to his famously hushed presence when he reads in public. It is a silence made of unwritten sentences. Of the feel of not to feel it. Almost (if not quite) of self-annihilation. Yet it is also the brilliance of concentration in which both tone and image lean into each other without falling, and hold each other and proffer some slight consolation. Like his hero Edward Thomas, Motion can create images and tones of such word-carried, world-wearied sadness that you accept their truth while simultaneously believing in their fictive grace. Truth and beauty: those dissimulators. Andrew Motion used to be their master. But in poem-sequences such as ‘Gospel Stories’, ‘Whale Music’, ‘A Glass Child’ and ‘The Death of Francesco Borromini’, Motion is now – in his late style - humble before them. The Customs House is redemptive. He has served his term. These poems are true poems.

Is the music of his poetry as finely judged as their tone? The first section of this book is something of an experiment. It comprises a series of war poems. These are ‘found poems’ – which is to say (Motion notes) ‘they contain various kinds of collaboration’. And the collaborations find their origins in oral and written reportage, and in war-time stories from veterans of the World Wars and the recent and current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. For example, in ‘The Golden Hour’ (which refers to the time required to keep a traumatised patient alive in surgery), an army surgeon addresses the reader:

For instance: one patient I remember had been in a blast situation

with no visible injury but we were not ventilating very well at all.

I put two openings in both sides of his chest with a big scalpel blade;

then I could stick my fingers in, and knew his right lung was down

because I could not feel it. However, I was now releasing trapped air

and the lung came up again. He has responded within the golden hour.

Because I could not feel it. The verbal truth of the war poems is fascinating in that their poetic music is almost completely surrendered in order to honour the spoken clarity of factual experience. This requires a sensitively engineered ear for line-break. Some of the material swings close to the prosaic, yet Motion’s deft lineation and deletions work double-time to preserve the true sense of natural speech. And Motion is generous as a translator of experience. He allows the hard-won details and voices to carry their own poetry. The voices of the war poems shift from the panoptic to a microscopic focus. Tight scenes possess intense light and energy. There is no desire to press a bright-red anti-war poetry button; no call for the trickery of literature; and no call above the quiet truths and sensibilities of those on the front-line. In terms of poetry and in terms of truth, The Customs House is an honourable, humbling achievement.

January 20, 2013

Mayakovsky Takes the Room: a review of The Slanting Rain by David Morley

‘I want to be understood by my country, nothing more.

but if I fail to be understood –

what then?,

I shall pass through my native land

at an angle, in vain,

like a shower

of slanting rain.’

Vladimir Mayakovsky

The Ferguson Room in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s renovated Stratford site is spare of decoration or furnishing. Diminutive, serious-looking it feels like a boardroom without a board table. Tonight it had been set up for stand-up, yet felt bare, faceless and business-like. The audience huddled at the tables (the temperature tempted no-one from their coats and hats). Sitting no less than a yard from the small, low, lit stage, we listened to faint strains of Shostakovich and, in a distant room, the children of Stratford-on-Avon cavorting in a play-room near a lovely if Arctic bar.

Then the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky strode in from somewhere behind me, megaphone in hand, his jacket brushing my shoulder as he whipped on to the stage, stalking the space and surveying us all quietly (“taking the room”, as he later put it), asking us if we liked poetry and reading us a poem. A quiet, almost Georgian piece. He read with slight respect. A certain bemused if worn beauty arose in the room. Certain lines beguiled: ‘While blizzards bonfire / underneath the windows’. “Did we like the poem?”, he asked. Few dared put up their hands (although I did, persuaded to quiet curiosity by the blizzard image). Mayakovsky demurred, scowled, exploded. With a burst of fury he dismissed the piece (which was by one of his ‘peasant-loving’ contemporaries), screwed the poem up and threw it to the floor – from where I later retrieved it.

“The Slanting Rain” is a one-man play in which the Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky is brought crackling into life by actor Ed Hughes. This touring production blasted into the RSC Stratford this week and, despite some of the grimmest weather of the winter, seems to be playing full houses. Ed Hughes’s depiction and enactment of artistic and political fury is remarkable in its power. His performance is a true tour de force.

What is really remarkable about the play, however, is the grace of his fury, the projection that Mayakovsky was a double-act within himself, tearing himself to pieces – individualism versus collectivism; private versus public (the play is very moving on Mayakovsky’s long-term love affair with Lily Brik); and the addiction of performance versus the solitude of composition - “ten lines a day”, he glowered, gloomily turning to me, “and ten lines was a good day!” I smiled back at the poet, but worried for him. (I worried for myself.)

What happens to a popular artist when their moment had passed? When their younger contemporaries view him as a has-been or, worse, a sell out? There are fascinating pictures of Mayakovsky in his well-tailored suits, sporting his famous yellow coat, a workers’ poet-god among the factory floors of post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. “Do you like my coat? It made me stand out like the sun”. I am not sure we liked the yellow coat, but the poetry, woven into every speech, was beautifully carried and dramatic. And that was one of the singular strengths of the script: it trusted the poetry, it let it breathe and unravel and capture the room.

What happens to a popular artist when their moment had passed? When their younger contemporaries view him as a has-been or, worse, a sell out? There are fascinating pictures of Mayakovsky in his well-tailored suits, sporting his famous yellow coat, a workers’ poet-god among the factory floors of post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. “Do you like my coat? It made me stand out like the sun”. I am not sure we liked the yellow coat, but the poetry, woven into every speech, was beautifully carried and dramatic. And that was one of the singular strengths of the script: it trusted the poetry, it let it breathe and unravel and capture the room.

We will never know if this is what it was like to be one among the adoring ‘five thousand’ who flocked to Mayakovsky’s readings (the people’s poet toured the country in the 1920s like a rock star) but it is always interesting to be reminded of the power of poetry at particular moments of history. “Poetry is the heart”, Mayakovsky intoned. And later, “But love is everything”.

Mayakovsky Takes the Room: a review of �The Slanting Rain� by David Morley

‘I want to be understood by my country, nothing more.

but if I fail to be understood –

what then?,

I shall pass through my native land

at an angle, in vain,

like a shower

of slanting rain.’

Vladimir Mayakovsky

The Ferguson Room in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s renovated Stratford site is spare of decoration or furnishing. Diminutive, serious-looking it feels like a boardroom without a board table. Tonight it had been set up for stand-up, yet felt bare, faceless and business-like. The audience huddled at the tables (the temperature tempted no-one from their coats and hats). Sitting no less than a yard from the small, low, lit stage, we listened to faint strains of Shostakovich and, in a distant room, the children of Stratford-on-Avon cavorting in a play-room near a lovely if Arctic bar.

Then the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky strode in from somewhere behind me, megaphone in hand, his jacket brushing my shoulder as he whipped on to the stage, stalking the space and surveying us all quietly (“taking the room”, as he later put it), asking us if we liked poetry and reading us a poem. A quiet, almost Georgian piece. He read with slight respect. A certain bemused if worn beauty arose in the room. Certain lines beguiled: ‘While blizzards bonfire / underneath the windows’. “Did we like the poem?”, he asked. Few dared put up their hands (although I did, persuaded to quiet curiosity by the blizzard image). Mayakovsky demurred, scowled, exploded. With a burst of fury he dismissed the piece (which was by one of his ‘peasant-loving’ contemporaries), screwed the poem up and threw it to the floor – from where I later retrieved it.

“The Slanting Rain” is a one-man play in which the Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky is brought crackling into life by actor Ed Hughes. This touring production blasted into the RSC Stratford this week and, despite some of the grimmest weather of the winter, seems to be playing full houses. Ed Hughes’s depiction and enactment of artistic and political fury is remarkable in its power. His performance is a true tour de force.

What is really remarkable about the play, however, is the grace of his fury, the projection that Mayakovsky was a double-act within himself, tearing himself to pieces – individualism versus collectivism; private versus public (the play is very moving on Mayakovsky’s long-term love affair with Lily Brik); and the addiction of performance versus the solitude of composition - “ten lines a day”, he glowered, gloomily turning to me, “and ten lines was a good day!” I smiled back at the poet, but worried for him. (I worried for myself.)

What happens to a popular artist when their moment had passed? When their younger contemporaries view him as a has-been or, worse, a sell out? There are fascinating pictures of Mayakovsky in his well-tailored suits, sporting his famous yellow coat, a workers’ poet-god among the factory floors of post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. “Do you like my coat? It made me stand out like the sun”. I am not sure we liked the yellow coat, but the poetry, woven into every speech, was beautifully carried and dramatic. And that was one of the singular strengths of the script: it trusted the poetry, it let it breathe and unravel and capture the room.

What happens to a popular artist when their moment had passed? When their younger contemporaries view him as a has-been or, worse, a sell out? There are fascinating pictures of Mayakovsky in his well-tailored suits, sporting his famous yellow coat, a workers’ poet-god among the factory floors of post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. “Do you like my coat? It made me stand out like the sun”. I am not sure we liked the yellow coat, but the poetry, woven into every speech, was beautifully carried and dramatic. And that was one of the singular strengths of the script: it trusted the poetry, it let it breathe and unravel and capture the room.

We will never know if this is what it was like to be one among the adoring ‘five thousand’ who flocked to Mayakovsky’s readings (the people’s poet toured the country in the 1920s like a rock star) but it is always interesting to be reminded of the power of poetry at particular moments of history. “Poetry is the heart”, Mayakovsky intoned. And later, “But love is everything”.

January 3, 2013

'My Eyes and Ears are Still Full': Judging the 2012 T.S.Eliot Prize by David Morley

This piece first appeared in The Guardian.

Judging the T.S. Eliot Prize has become no less of an undertaking than the Man Booker. Prose may be longer but poetry is denser. This year saw 131 poetry collections arrive in early September, some as marked-up proofs bearing the handwritten corrections of poets. How their precisely perfect notations reminded you that every one of these manuscripts was the labour of years – and the labour of tears. I arranged my world around reading them, and I read every single one. My life was put aside for two months; certainly any thought of writing poetry was removed. It has been the strange and compelling time. The process of submitting myself to this huge whirl of words has been self-annihilating. I was not myself. I became all eye and ear.

What do you hold on to? It helped that I had already reviewed over 40 of the submitted books this year during a manic reviewing programme for Poetry Review under the editorships of George Szirtes, Charles Boyle and Bernardine Evaristo. I already knew, for example, how much I liked a lot of the stuff coming out this year from Salt Publications, Nine Arches Press, Seren, and the brilliantly-named Knives, Forks and Spoons Press. I was disposed to read harder into the volumes of some of the more fugitive presses. I don’t care if a collection is from Picador or Waterloo Press or Two Rivers Press. I stood to attention and gave every poetry book its due.

I subjected each book to a series of physical and aural tests. Listening in on a poem, I read aloud (sometimes to myself or to Warwick University students); or I read in total silence; and sometimes I read against silence. I placed headphones on my ears and filled my mind with other music – Mahler, bird calls, The Beatles – and then I read a poetry book at the same time to test which music sang more strongly. I also took the poems into the fields and read them while I was walking. If they could make me stop walking they were doing very well (that test goes for people too). In these ways, and several others, the number of books was reduced to around 20. A whirlpool of words rang in my mind.

Which books did I love but which failed to win through to the shortlist? My personal favourites included Jon Stone’s School of Forgery, Lesley Saunders’ Cloud Camera, Richard Price's Small World, Maria Taylor’s Melanchrini, Andrew Motion’s The Custom House and – all three judges loved this one - William Letford’s astonishing debut Bevel. And what of the shortlist? You have to remember that of the 10 books there are 4 that are already pre-chosen, the Poetry Book Society Choices from Simon Armitage, Paul Farley, Jorie Graham and Sharon Olds. What we were selecting were 6 books by 6 poets. I am proud of them all. Stand to attention, Sean Borodale, Gillian Clarke, Julia Copus, Kathleen Jamie, Jacob Polley and Deryn Rees-Jones! I salute you all. I agree with Michael Longley in saying there's nothing clichéd about our list, that we went with the words on the page. But we also went with the sounds, and my ears and eyes are still full of them.

David Morley's Blog

- David Morley's profile

- 13 followers