Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 347

November 2, 2019

Cash Back

AMAZON.COM��is the world���s fourth most valuable company, based on its stock market capitalization. At that size, it isn���t about to get bought by another company. It doesn���t pay a dividend. The last time it repurchased its own shares was seven years ago.

Now, imagine this continued���no buyout, no dividend, no stock buybacks���until the sad day arrives when Amazon goes the way of buggy whip manufacturers. Result: There���s a good chance its shareholders would, over the company���s history, have collectively made no money. Sure, some investors would have bought low and sold high. But in aggregate, investors would have got pretty much zilch.

This is not to pick on Amazon���it gets a bigger slice of my income than any other retailer���but rather to highlight two key points. First, most companies eventually disappear. Second, before that happens, we should want them to return as much cash to shareholders as possible.

In my investing lifetime, I���ve seen countless companies fall from grace. At their peak, corporations like IBM, Wal-Mart, Microsoft and General Electric seemed unstoppable. Yes, they���re still huge companies. But they no longer inspire awe and their brightest days are likely behind them.

This is all too common. It isn���t that companies necessarily grow complacent. Rather, new competitors emerge with cheaper, faster, better ways of doing business���and the old guard is swept away by a ���gale of creative destruction,��� to use the memorable phrase from economist Joseph Schumpeter.

Consider the 90 years through December 2016. According to a study by Hendrik Bessembinder, a professor at Arizona State University, there were almost 26,000 publicly traded U.S. companies during this stretch. They were listed for an average of just seven and a half years. Some of the companies that disappeared would have been bought out���but many others would have been delisted as they struggled financially on their way to extinction. In fact, only 36 stocks were around for the full 90 years.

To get a sense for corporate America���s constant upheaval, check out the American Business History Center���s ranking of the largest U.S. companies, based on revenues. Hit the replay button at the top of the page and you���ll see how, over an astonishingly short 24 years, General Motors and Ford Motor were toppled from the top of the ranking, while Apple, Berkshire Hathaway and Amazon soared to claim three of the top five spots.

We look around us and imagine that today���s largest corporations will always be with us, but that simply isn���t the case. That brings me to my second key point: We should want companies to return cash to shareholders���and preferably lots of it.

Yes, today, there���s a disdain for dividends, because they���re immediately taxable, though usually at a favorable rate. Yes, there���s widespread sentiment that management should be left to reinvest corporate profits. While this might make sense in a corporation���s fast-growing early days, it���s not desirable over the long haul.

Why not? Take General Motors, which was delisted from the stock market in 2009 after filing for bankruptcy. The share price when it was delisted was 61 cents, down from $93 less than a decade earlier. (Since late 2010, a new GM stock has been trading, but that was the result of a subsequent initial public offering.)

As Bessembinder notes in his paper, GM paid out more than $64 billion in dividends over the decades prior to its bankruptcy, plus it repurchased its shares on multiple occasions. That means that, even though the stock ended up worthless, its shareholders still made money. ���GM common stock was one of the most successful stocks in terms of lifetime wealth creation for shareholders in aggregate, despite its ignoble ending,��� Bessembinder writes. In fact, over the 90 years that his study covers, GM ranked eighth among all U.S. corporations when it came to creating wealth for investors.

What does all this mean for you and me? The biggest lesson: It���s imperative to diversify. To protect ourselves against the gales of creative destruction, we need to spread our money across a slew of companies, rather than hitching our fortunes to a few companies that may end up in the corporate graveyard.

I would also think twice before reinvesting a corporation���s dividends solely in that company���s stock. I used to be a fan of dividend reinvestment plans, where you can automatically reinvest your dividends in additional company shares. Indeed, that���s how I first got started as an investor. Problem is, if most companies eventually disappear, you really want to take your dividends and spread them across a slew of companies. That way, you won���t be plowing ever more money into a company that���in all likelihood���will one day disappear.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Crazy Like a Fox,��Guessing Game��and��

Improving the Odds

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Crazy Like a Fox,��Guessing Game��and��

Improving the Odds

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Cash Back appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 1, 2019

Scenes From a Life

ONE SUNDAY, my son was lamenting that he had a school project due the next day, but hadn���t yet taken any steps to get it done. When I asked what his plan was, he replied, ���I could use a really good montage right about now.���

For those who aren���t procrastinating teens with a father who delves into media literacy, a montage is a series of quick shots in a TV show or movie that accelerates time around a theme���that theme often being the effort and time expended to achieve a goal. Think of the athlete training for the big event, the artist trying to create, the business group trying to formulate a project, or even a building slowing going up. One sees the passage of time condensed on screen, perhaps with a brief stumble or glint of frustration along the way. But in the end, there���s the assured and ultimate victory.

Such shows always detail the end result, but the long road to success seems summarized. Why is it truncated? You know why. It���s boring. It���s tedious. It���s often discouraging. Most of the time, those on the journey have no assurance of where the road will end.

But that���s life.

Think of the things you enjoy right now. A good relationship with a wonderful partner? It wasn���t built in a moment���s stare into each other���s eyes, but rather from working through issues, everything from easy ones about the kids to tough ones about the best way to load the dishwasher.

Most people who visit sites like HumbleDollar are already attentive to financial issues. But what are the messages that movies and TV shows give to the average money handler?

Wealth is often suddenly and fortuitously thrust upon someone.

Saving is shown in a quick montage, starting with a few cents in the piggy bank and then���poof���the couple have the money they need.

Spending for today is shown as rewarding and yet later there���s almost never a financial reckoning.

To be sure, no single depiction will cause a viewer to become a spendthrift. But just as stalagmites are slowly formed by constant dripping, so too are our attitudes about money. There are many factors at play, but movies and TV shows aren���t helping. As a media literacy geek, I could demand that entertainment be more financially realistic. But���speaking of being realistic���people want to see the fun parts of life. It���s why few documentaries are blockbusters.

How can we nudge ourselves along the long, uneven path of saving and delayed gratification? Perhaps we should treat our financial life like a movie, especially when we���re at that fork in the road where there���s a choice to spend or save:

We hear a Rocky -like theme song as we delay spending���s immediate pleasure and instead struggle to keep the money in our wallets. Alternatively, we could have a general theme song to our life that reinforces the notion that everything is part of a long-term plan. My choice is�� Green Onions .

We could imagine an audience is watching us as we make that spend or save decision. In fact, there may really be an audience���consisting of our children, whose money habits will be influenced by what they see.

We have a cutaway ���stumble��� scene in our montage where we spend too much. Then we shake our heads, pick ourselves up and get back on the savings path.

It���s also important to leave room for a sequel. We achieve our short-term savings goal, so we climb the stairs and raise our arms in victory. There will, however, be other, greater challenges ahead. We might even be laid low and have to struggle to reclaim our earlier victory. But we will prevail.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught��economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Changeup Pitch,��Bored Games��and Shame on Us. Jim���s three-book series on teaching behavioral economics and media literacy,����

Media, Marketing, and Me

,

��is

��being published in 2019.��Jim lives in Granada, Spain, with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at��

YourThirdLife.com.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught��economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Changeup Pitch,��Bored Games��and Shame on Us. Jim���s three-book series on teaching behavioral economics and media literacy,����

Media, Marketing, and Me

,

��is

��being published in 2019.��Jim lives in Granada, Spain, with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at��

YourThirdLife.com.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Scenes From a Life appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 31, 2019

Decision 2020

FALL IS MY favorite time of year, but there used to be one thing I dreaded: picking a health plan for the year ahead.

Many folks don���t know how to evaluate their health insurance options. I used to be in that group���until I adopted a fairly straightforward process. Bear with me while I walk you through the sort of choice you might face as an employee. The same analysis can be used if you���re buying insurance on your own.

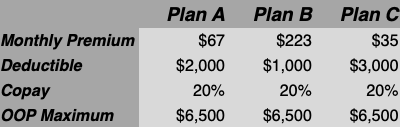

Health insurance costs have four components: premiums, deductibles, copays and out-of-pocket (OOP) maximums. Your company should provide these values for each of the plans on offer. It���s important to distinguish between employee costs���the money you actually pay���and medical costs, which are the costs that medical providers charge and which may be covered by insurance. My four-step process is as follows:

Calculate the total annual premium. This is the minimum amount you���ll pay during the year. Think of it as the best-case��scenario. This is the cost if you���re perfectly healthy and never use medical care.

To the results from step No. 1, add the deductible for each plan. Taken together, this is the maximum amount you���ll pay before copays come into play.

Subtract the deductible from the OOP maximum. Let���s say that number is $4,000. Divide that $4,000 by the copay percentage, which might be 25%. You���ll need to turn the 25% into a decimal by dividing it by 100, so it becomes 0.25. If you divide $4,000 by 0.25, you get your answer: $16,000. To that $16,000, add the deductible. Result? This is the total medical costs���much of which would be paid by the insurance company���that you���d need to incur to hit the out-of-pocket maximum. That OOP would be your share of these costs.

Add the premium amount from step No. 1 to the OOP maximum. This is the maximum employee cost you can incur in a year. Think of it as the worst-case��scenario.

Confused? With any luck, an example will help. Check out the table below. This is a real-life example from a midsize company in 2018. The company offered three plans with different premiums and deductibles. Note that the copay and OOP maximum is the same for each plan.

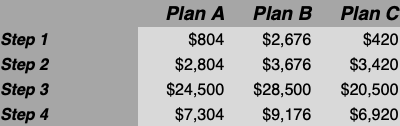

Next, let���s turn to our second table, which shows the results of the four-step process.

Next, let���s turn to our second table, which shows the results of the four-step process.

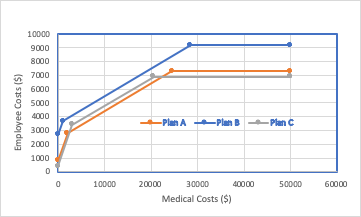

That brings us to the graph below. The horizontal axis shows the total medical costs incurred, while the vertical axis is the cost an employee pays at any given total medical costs.

That brings us to the graph below. The horizontal axis shows the total medical costs incurred, while the vertical axis is the cost an employee pays at any given total medical costs.

When you have zero medical costs, your total cost as an employee is equal to the total annual premium you pay. You hit the first bend in the line when your medical costs for the year equal your deductible. Until you hit that deductible, all medical costs come out of your pocket.

When you have zero medical costs, your total cost as an employee is equal to the total annual premium you pay. You hit the first bend in the line when your medical costs for the year equal your deductible. Until you hit that deductible, all medical costs come out of your pocket.

Once you reach your deductible, you go into a copay situation���the line beyond the first bend. The copay for our three plans was 20%. In other words, for every $5 of medical costs you incur after meeting the deductible, you have to pay $1. The three lines in the chart keep rising until you���ve accumulated enough medical costs so that the combination of your deductible and 20% copays add up to your OOP maximum. Once you reach this point, the line flattens, because you���ve reached the maximum in medical costs you���ll owe for the year.

If you knew exactly how much medical costs you would incur over the next year, it would be easy to look at the graph and pick the best option. But unfortunately, it���s impossible to know. What to do? After looking at these types of choices for many years, I���ve developed a rule of thumb: Pick the plan that does the best job of minimizing both the low end and the high end.

Plan C has the lowest minimum cost���because it has the lowest premium���and also the lowest maximum cost, as reflected in the premium plus OOP maximum. Result? If you had a very healthy year with no medical care, you���d have the lowest cost. And if you had a very unlucky year, with high medical costs, you���d still have the lowest employee cost. In between those two extremes, it���s a mixed bag. Still, I would pick plan C. I know my best- and worst-case costs, and anything in between is acceptable to me.

The values shown here are for an employee only. Most plans I���ve seen have higher costs for different family sizes. You can use the same process, but the conclusions may be different once additional family members are considered. For many years, my wife and I both had access to good medical insurance. We would do the analysis on both sets of plans, and then pick the best plan for our family.

Another consideration: Medical premiums are usually paid out of pretax income, effectively reducing an employee���s cost. You may also be able to pay out-of-pocket costs using pretax income if, say, you can fund a flexible spending account or you have a high-deductible health plan with a health savings account attached. Sometimes, employers contribute to a health savings account, and that can tip the balance in favor of a high-deductible plan.

Finally, in addition to costs, you���ll want to look closely at which doctors are considered in-network by each plan. Got doctors you���ve used for years? To continue seeing them, you may need to favor a plan that���s less financially attractive.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Our Charity,��Solo Effort��and��What Number. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Our Charity,��Solo Effort��and��What Number. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Do you enjoy articles by Rick and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Decision 2020 appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 30, 2019

What’s Your Plan?

ARE PENSION PLANS superior to 401(k) plans? I have a soft spot for my pension plan, especially when that payment hits my checking account each month. But pension plans were never as common as people imagine���and, for today���s workers, 401(k) plans may be a better bet.

The traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan is all but gone from the private sector. Companies have terminated them, frozen them for new hires or converted them to so-called hybrid plans, which are technically DB plans, but they look more like a 401(k).

When I worked in employee benefits, I oversaw the introduction of a hybrid plan���a cash balance plan���in 1995. The plan was for new hires and it still exists. Workers receive a percentage of pay into a notational account, with the percentage based on their years of service and their age. Participants can see their account���s value grow. The funding is the same as any DB plan and the standard payout option is a life annuity. But during all the years I managed the plan, employees elected a lump sum every time, thereby voiding the idea of a pension. In other words, it was supposedly a pension plan, but many employees thought of it more like a 401(k).

Many Americans never had a pension plan. The peak was about 60% in 1960 and now it���s between 4% and 15% in the private sector. The percentage varies based on the definition used. Some workers have both a DB plan and a 401(k) or similar plan. The 4% represents those with only a defined benefit plan. By contrast, DB pensions are far more common in the public sector, with participation at perhaps 77%. But again, the percentage varies by survey.

If you consider those with any type of retirement plan���pension plan, 401(k) plan or something else���the numbers are roughly 50% private sector and 80% public sector. I see some irony here. Few Americans have a pension, many have no employer plan, and many struggle both to save for retirement and to live on Social Security once retired. Yet all Americans pay taxes, especially state and local taxes, which then fund fairly generous pensions and benefits for the public sector.

Although workers tend not to think about it, a pension is part of their total compensation. In the absence of a pension and other benefits, cash compensation should���in theory���be higher. How much is a pension worth to employees? An employer can fund a good DB pension plan for about 8% of payroll.

Yet reductions in employee benefits never seem to result in higher compensation. In all my decades managing employee benefit programs, I never saw a benefit reduction, including termination of a pension plan, translate into higher cash compensation. In today���s world, cuts are routinely made in health benefits, but those savings never seem to end up in pay.

A 401(k) or similar defined contribution (DC) plan has the potential to provide a good retirement income. In fact, I���d argue that a DC plan is now better for most workers. Why? To get value from a DB plan, you need longevity with an employer. But today, the average tenure at one employer is about four years. That isn���t sufficient time to become vested in a DB plan, let alone accumulate a meaningful future benefit. Dinosaurs like me who worked for one company for 50 years are truly extinct���but we have good pensions.

According to Fidelity Investments, the average employer contribution to a 401(k) plan is up to 4.7%. If you include that employer contribution, saving at least 10% of income on a tax-advantaged basis should not be that hard for anyone with a fulltime job. But to get value from a 401(k), you need to contribute at least enough to get that full matching contribution���and you need to keep the money in a retirement account when you change jobs, rather than cashing out your 401(k) and spending the money.

But what about the big payoff from a pension plan���that monthly check you get in retirement? That is indeed a crucial difference between the typical DB and DC plan. A pension comes with a life annuity, whereas a 401(k) plan leaves you with a lump sum.

Today, annuities within a 401(k) are possible, but rare. Congress is attempting to encourage more annuities by lowering the fiduciary risk for plan sponsors. But even if that happens, we have a long way to go���because many folks resist the idea of annuitizing. Indeed, whether folks have a pension plan or a 401(k), they seem to prefer a lump sum payout to regular monthly income.

The most common argument I routinely heard against purchasing an annuity with a 401(k) balance is, ���I���ll lose the money if I die early.��� True. But the fact is, if you���re dead, what you���ve lost is irrelevant. Instead, at that juncture, what matters are your spouse and any children still at home. They can be covered by a ���joint and survivor��� annuity that continues making payments to your surviving spouse.

Moreover, you face similar risks if you have a DB plan. While working at an employer with a pension plan, you have, in theory, given up 8% or so in cash compensation for that pension. What if you switch jobs before vesting or you die early? Like the annuity buyer, you���ve also left money on the table. Maybe that���s why pension plan participants, when offered a choice, so often opt for a lump sum. Result: They spend their retirement with the same financial uncertainty suffered by those who funded 401(k) plans and then refuse to annuitize.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Staking Your Claim,��What Do You Mean��and��Open Season.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Staking Your Claim,��What Do You Mean��and��Open Season.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy��reading articles by Dick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a��donation.

The post What’s Your Plan? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 29, 2019

7,000 Days

MY LAST CLOSE relative���other than my kids���recently experienced major health issues. That prompted me to reflect on my own potential longevity. I���ve got 7,000 days to go, more or less, or at least that���s what the Social Security Administration���s��longevity calculator tells me.

It seems like a big number, but it���s less than 20 years and just a quarter of a U.S. male���s average 29,000-day lifespan. Each day in retirement, we get to decide how to utilize one of those precious remaining days���whether to use it wisely or possibly fritter it away.

Of course, my actual number may differ greatly from 7,000. On the plus side, I have good health, a regular exercise routine, a decent diet and access to solid health insurance. But none of my family has lived a long life, so I may be DNA challenged. Some life expectancy calculators, with more individualized lifestyle inputs, give me a solid shot at notching an additional 4,000 days, for 11,000 total. But I���m not counting on it. Besides, the more relevant number is how many days we���re able to live an active lifestyle���walking, traveling, swimming and so on���and that���s likely considerably less than 7,000.

The upshot: Every retirement day effectively becomes its own critical, time-management challenge. Time and health are truly our most precious assets, rather than the financial assets on which we so often focus.

The implication? I regularly find myself debating whether to do something:

That frees up or improves later time.��In this category, I���d include doing chores, maintaining my home and cars, exercising, managing financial assets or planning future activities.

Fulfilling or engaging.��That might include interacting with family and friends, traveling, working, reading, walking, exploring a hobby or writing another of these articles.

Frivolous or somewhat wasteful.��I���m talking about things like watching TV, surfing the internet, playing video games, having a few drinks or stuffing myself with bon-bons.

Everyday life���category No. 1 above���tends to consume a majority of our time. That means we aren���t constantly forced to decide between activities that are fulfilling and those that are wasteful. That���s probably a good thing. It would be tough to spend all day choosing between worthy and unworthy activities.

To be sure, some activities may be fulfilling for some folks, while seeming frivolous to others. My wife finds shopping engaging. I don���t. TV is the area that provides perhaps the greatest variations in time invested. I���m among the minority who have never seen a single episode of Game of Thrones, Seinfeld��or Friends. I���d rather do almost anything than watch something.

In fact, I���m off to have a drink and eat a bon-bon, which might strike you as a bad use of time. But I���m also going to call my kids���because you never know what day 6,999 might bring.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. ��His previous articles include Window Dressing,��Creeping Costs��and��Cashing In.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. ��His previous articles include Window Dressing,��Creeping Costs��and��Cashing In.

Do you enjoy articles by John and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post 7,000 Days appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 28, 2019

Alphabet Soup

WHEN YOU NEED expertise, you hire an expert. Water leak? Call a plumber. Electrical issue? Call an electrician. But when it���s a financial issue, the choice may not be so clear. Do you go to a CKA, a GFS or maybe a C3DWP? Chances are you haven���t heard of these designations.

I have 10 letters in my name. I also have 10 letters after my name: CPA, CISA and MBA. What do they mean? Only that, after a lot of education and passing a lot of tests, I met the minimum qualifications to claim these credentials.

Yet these mysterious acronyms have become a lucrative business. A growing number of organizations sponsor financial credentials���and legions of financial advisors want to bolster their credibility by building their acronym resume.

But do the acronyms themselves have any credibility? FINRA, the securities industry regulator, has a list of financial designations on its website. The list has 208 entries���and, even then, it isn���t complete. Read through the list and you���ll see designations focused on helping individuals in their financial life, as well as designations that deal with issues faced by companies sponsoring employee benefit plans. For everyday Americans, someone with these credentials might��be helpful. But other designations focus on the marketing of financial services, retirement plan administration and other specialties���qualifications that might not provide any value to the typical family seeking financial advice.

Besides listing the acronyms, FINRA provides the name and status of the designation, the issuing organization, the requirements to earn the credential and how to file a complaint against someone with the credential. Granted, some credentials are obscure or even cover nonfinancial disciplines. Did you notice my CISA isn’t on the FINRA list?

The list provides a chance to educate yourself on the competencies a credential holder should offer and whether those competencies might be useful to you. Some credentials have very strong ethics and fiduciary standards���and others not so much. One of the sponsoring organizations on the FINRA list offers 12 different designations that only require an advisor to pay a monthly fee to the sponsoring organization: There are no education requirements, no testing, no fiduciary requirement. Just pay the monthly fee and add the acronym.

Will the designations held by your advisor be of any advantage to you? Ask these eight questions:

What credentials does your advisor hold?

What does the FINRA list say about each credential?

Is the credential being actively supported���or has the sponsoring organization gone out of business?

Do an internet search on the sponsoring organization. Does it appear to have integrity?

Does the designation signify anything���or is your advisor touting a credential that involves little or no education requirements?

Does the credential mean your advisor is better qualified to help you?

Does the sponsoring organization require credential holders to act as a fiduciary?

Contact the sponsoring organization. Have there been any disciplinary issues involving your advisor?

Mark Eckman is a data-oriented CPA with a focus on employee benefit plans. His previous articles were Financial Pilates and��Giving Voice. As Mark approaches retirement, he’s realizing that saving and investing were just the start���and maybe the easy part. His priorities: family, food and fun.��Follow Mark on Twitter��@Mark236CPA.

Mark Eckman is a data-oriented CPA with a focus on employee benefit plans. His previous articles were Financial Pilates and��Giving Voice. As Mark approaches retirement, he’s realizing that saving and investing were just the start���and maybe the easy part. His priorities: family, food and fun.��Follow Mark on Twitter��@Mark236CPA.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Alphabet Soup appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 27, 2019

Staying Home

A UNIQUE EVENT occurred earlier this month: A group who call themselves the Bogleheads held an investment conference in the Philadelphia area, near the headquarters of Vanguard Group. Since its inception in 2000, this annual gathering has brought together fans of Vanguard���s founder, Jack Bogle, who died earlier this year.��

Bogle was beloved by his fans for his authenticity and iconoclastic views. He was so self-assured, in fact, that���after he retired from Vanguard���he didn���t hesitate to share his opinions, even when he was in the minority and even when he disagreed with Vanguard���s official position.

Among the points on which Bogle disagreed with Vanguard was the question of international diversification. For decades, until the end of his life, Bogle was consistent in his view that investors need not���and probably��should��not���diversify their portfolios outside the U.S. Bogle said that his own portfolio was 100% domestic and he recommended that others do the same.

Vanguard���s official position, on the other hand, is that investors should structure their portfolios to pretty much mirror the overall makeup of world stock markets, of which U.S. shares currently account for somewhat over half. For instance, on its website, Vanguard��recommends��that investors allocate 40% of their stock portfolio to international markets.

In Bogle���s view, there was no need for international diversification, because the U.S. is ���the most innovative economy, the most productive economy, the most technologically advanced economy and the most diverse economy.��� To the extent that an investor desired exposure to foreign markets, Bogle pointed out that domestic companies derive such a large part of their revenue���more than 40%���from outside the U.S. that it was unnecessary to buy the stocks of foreign companies.

���If you own a domestic stock fund, you already own an international fund,��� he said. Bogle also highlighted a number of risks, including currency depreciation and more limited shareholder protections outside the U.S. For all these reasons, he said, ���I don���t do international.���

Vanguard���s official view, on the other hand, is based on the logic that investors shouldn���t exclusively favor one country���s stock market just because that���s where they happen to live.

My view: I believe international diversification is useful, but I absolutely worry about the risks that Bogle always cited. Even Vanguard’s��own data��indicate that a large majority of foreign stocks��� diversification benefit can be achieved with an allocation of just 20%, which is why that���s what I recommend.

I���ve been thinking about this more in recent weeks, as the protests in Hong Kong have raged and as the NBA has found itself mired in controversy, just because the general manager of the Houston Rockets issued��one tweet��that Chinese authorities didn���t like. Even after deleting the offending tweet, the financial fallout for the NBA has been��painful.

These events reinforce my view that, though the U.S. is hardly perfect, our economic system is much less imperfect than many others. And this is why I���m happy to limit exposure to international stock markets���and especially emerging markets, where constraints on individual freedoms and government economic interference are both commonplace.

Still, I wouldn���t recommend taking your international allocation to zero. Earlier this month, The��Wall Street Journal described how the consumer market in China��has changed��in recent years. Owing in part to improvements in domestic brands, as well as to growing patriotism, Chinese consumers have moved in large numbers away from foreign brands. Over the past 10 years, for example, foreign smartphone manufacturers have lost a mindboggling 78 percentage points of market share in China. Today, Apple is down to just 9% market share, while four Chinese vendors dominate with a combined 84%.

The implication for investors: Owning stocks in American companies may no longer provide sufficient diversification. In the past, it may have been enough to own companies like Apple, Nike and Hershey, since each had such broad international reach. But if they���re at risk of having their wings clipped outside the U.S., and particularly in China, you may want to broaden your portfolio to include their Chinese competitors Huawei, Li Ning and Three Squirrels.

No question, I share Jack Bogle���s concerns about international markets. But for the benefit of your portfolio, I recommend dipping a toe into foreign stocks.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Happiness Formula,��Yet Another Reason��and��Peter Principles

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Happiness Formula,��Yet Another Reason��and��Peter Principles

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy the articles by Adam and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post Staying Home appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 26, 2019

Crazy Like a Fox

THERE���S A MADNESS to crowds���but also great wisdom.

Each of us knows very little about the world. But between us, we know an extraordinary amount. Every time we buy or sell a stock, we each draw on the knowledge and insights we have, and we effectively vote on whether we think the stock���s price should be higher or lower. Because today���s market prices reflect our collective wisdom, it���s hard to find shares that are badly mispriced. Result: Over the long haul, we���re highly unlikely to overcome the drag from investment costs and outperform the market indexes.

Moreover, market prices don���t just tell us about underlying value. They can also be a good guide to the future. I have no idea what inflation will be over the next decade and I���ve seen scant evidence that the economy is slowing. But investors have offered their collective opinion: The difference in yield between conventional Treasury notes and inflation-indexed Treasurys suggests annual inflation will run at 1.6% over the next 10 years, while the recent inverted yield curve tells us that a recession is a distinct possibility.

But while markets can seem all-knowing, they can also seem utterly mad. Who hasn���t watched the movement of major indexes and individual investments, and thought, ���That���s totally nuts���? Dot-com stocks in the late 1990s. Housing prices in 2005 and 2006. Global stock markets in early 2009. Bitcoin. Negative interest rates. Need I say more? When investors are collectively exuberant or scared, crazy things can happen.

So are crowds wise or foolish���or could they possibly be both? You see this quandary reflected in the ongoing debate over investors��� behavioral mistakes. Do these mistakes affect the market���s so-called efficiency���the degree to which market prices reflect underlying fundamentals?

Some experts argue that securities are always priced correctly. These experts don���t preclude the possibility that some investors act foolishly. But their foolishness isn���t sufficient to distort market prices, because their ignorant trades are cancelled out by the actions of better-informed investors.

Other observers allow that foolish investors can cause security prices to stray from what���s justified by underlying fundamentals. But these distortions are sufficiently random���and sufficiently costly to exploit���that the market remains extremely difficult to beat. I���m firmly in this camp.

But whether markets are always efficiently priced or not, the result is the same: We���re highly unlikely to outperform the market averages, which is why broad market index funds make so much sense. That contention is backed up by both logic and real-life evidence.

The logic: Before investment costs, investors collectively must match the performance of the market averages, because together we are the market. Meanwhile, after costs, we inevitably lag behind. To be sure, in any given year, some investors will get lucky and beat the averages. But as a group, we���re destined to trail the market by a sum equal to the investment costs we collectively incur. This isn���t just the opinion of some ink-stained wretch. Rather, it���s irrefutable logic.

What about the evidence? Consider three studies from S&P Global. First, there���s the so-called SPIVA study, which compares actively managed stock mutual funds to S&P indexes. Depending on the category, S&P found that between 79% and 98% of U.S. stock mutual funds failed to outperform their benchmark index over the 15 years through year-end 2018.

S&P Global conducts a similar study of institutional money managers���and the results from this second study are almost as dismal. After fees, 76% of institutional money managers focused on the U.S. stock market underperformed the broad market over the past 10 years.

While most money managers lag behind the market averages, a minority do indeed shine. Problem is, it���s awfully hard to identify these winning managers ahead of time. That brings us to the third study from S&P Global: Its ���persistence scorecard��� looks at whether winning managers keep winning. The answer, alas, is no���which means buying actively managed funds with strong past performance is unlikely to garner us market-beating results.

The bottom line: Crowds can behave foolishly. But does that make the markets easy to beat? Only a fool would believe it.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include��Guessing Game,��

Improving the Odds

��and��

50 Shades of Risk

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include��Guessing Game,��

Improving the Odds

��and��

50 Shades of Risk

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Crazy Like a Fox appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 25, 2019

Changeup Pitch

WHEN WE WATCH advertisements, we tend to think of ourselves as stationary, with the marketers coming to us and then, if we don���t respond, heading elsewhere. Like an Einstein relativity paradox, however, we observers are also in motion, being coaxed toward the marketer, often without knowing it.

A good business knows its customer niche���and good marketers know how to speak to that niche. Customer niches are defined by demographic attributes. When I discuss these attributes with students, I bring up King Arthur���s quest for the Holy Grail. But in this case, marketers are seeking their product���s GRAIL: gender, race or ethnicity, age, income and lifestyle.

Not every product pitch is delineated based on all five categories. Toothpaste is not marketed by race or ethnicity. Some distinctions are artificial. Yogurt is equally healthy for men and women, but it���s mostly pitched to women. To the extent that a product-pusher can say, ���this is perfect for you,��� potential customers respond positively.

Take money management. It���s potentially beneficial to all demographics. You might assume that the pitch for such services would mainly be a logical one that emphasizes, ���We can grow your money.���

TD Ameritrade���or TD to its friends���is a big marketer of such services. Of late, it���s produced a series of ads called ���The Green Room.��� The ads are shot in a largely green setting, a comforting color that no doubt evokes wealth. An advisor-come-therapist talks to people in a semi-casual way about their aspirations and what TD can do to help. The label ���Green Room��� also evokes the name given to a studio prep room, where guests ready themselves for the big show.

The customers in the ads are surrogates for the real customers viewing the ads at home. In pursuit of the GRAIL, TD strives to have actors of different race and gender. Age tends be older. This makes sense, since the topic is typically preparing for retirement. Income is skewed higher, as TD���s services are geared toward those who have the luxury of socking away extra money.

The most noticeable marketing sleight of hand regards lifestyle. By making a series of ads with similar but slightly different appeals, TD can speak to the:

Technical numbers person

Sports analogy guy

Non-detailed person

Transitioning empty-nesters

Go-getting young professional

The changes in the actual sales pitch���what TD can do for each type of person���are accentuated by subtle changes in the setting. The non-detailed person���s background is dominated by photos and a large picture of a bull fighting a bear. Meanwhile, the tech person and sports guy are each surrounded by graphs, as well as a scoreboard in the latter case. Most casually drink coffee from mugs, but the young professional���s ad has an obvious espresso machine. It���s all designed to have you, the potential viewer, place yourself on the green couch with the person you most identify with.

My goal here isn���t to single out TD Ameritrade. Other financial firms do something similar with their advertisements. What���s the overriding goal of such ads? TD and other financial firms may be selling rational money management. But their ads are working a different angle. As the viewer, your brain may be musing about money. But your heart is thinking, ���That���s me.���

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught��economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Bored Games,��Shame on Us��and��Under Attack. Jim���s three-book series on teaching behavioral economics and media literacy,����

Media, Marketing, and Me

,

��is

��being published in 2019.��Jim lives in Granada, Spain, with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at��

YourThirdLife.com.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught��economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Bored Games,��Shame on Us��and��Under Attack. Jim���s three-book series on teaching behavioral economics and media literacy,����

Media, Marketing, and Me

,

��is

��being published in 2019.��Jim lives in Granada, Spain, with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at��

YourThirdLife.com.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Changeup Pitch appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 24, 2019

Staking Your Claim

WHEN SHOULD YOU claim Social Security? The optimum date for starting retirement benefits is the subject of much debate and analysis. For most people, however, it���s a simple matter of when they need the cash���and, indeed, many folks claim as soon as they’re age 62 and eligible. The experts can run models all they want. But when it comes to Social Security, it seems necessity and emotion rule.

One thing is clear, though: There���s no validity to taking your benefits as soon as possible, and thereby ending up with a permanently lower monthly benefit, simply because you believe Social Security won���t be there for you. Congress has failed to heed warnings from the program���s trustees for nearly 35 years. Still, Social Security isn���t going anywhere. Take a look at the conclusion on page five of the latest annual report: Even when its trust fund is depleted, Social Security will still be able to cover 77% of scheduled benefits.

I love this quote from a recent article: ���If you���re healthy and expect to live a long time, you should maximize benefits received late in life by delaying��� the start of Social Security benefits. The problem: How could you possibly know to expect a long life?

If you have the fortitude to look, you might try the handy life expectancy calculator on��Bankrate.com. If not, consider the Social Security Administration���s actuarial tables: At age 62, the life expectancy for a male is 21.6 years, at age 65 it���s 17.9 years and at 70 it���s 14.4 years.�� A female lives two to three years longer, on average.

But many Americans will beat those odds. ���The 85 and over population is projected to more than double from 6.4 million in 2016 to 14.6 million in 2040,��� says the Department of Health and Human Services. Remember, once retired, a stock market decline, falling bond prices and rising inflation aren���t your biggest problems. Instead, it���s longevity���and hence the risk you���ll outlive your money. A larger Social Security check helps protect against that risk.

The goal of Social Security is to provide a safety net, but not full salary replacement and certainly not sufficient income to maintain your preretirement lifestyle. In Franklin Roosevelt���s words from 1935, Social Security offers ���some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age.���

Unfortunately, Social Security has become more than just a ���measure of protection.��� For far too many older Americans, it���s their major source of income. Among elderly Social Security beneficiaries, 48% of married couples and 69% of single individuals receive 50% or more of their income from Social Security. Meanwhile, 21% of married couples and 44% of single individuals rely on Social Security for 90% or more of their income.

Social Security is so complicated that no average person can navigate the benefit claiming choices. In fact, I suspect most people are unaware of their choices or even the questions to ask.��Claiming strategies are most complicated when a��spouse is involved. Should you both start at the same time? Should one delay until a later age? Can delaying the main breadwinner���s benefit increase a spouse���s benefit?

Several years ago, Boston College���s Center for Retirement Research published an interesting paper entitled, ���Should You Buy an Annuity From Social Security?” Its analysis looked at using your savings to supplement income until age 70, thereby allowing your Social Security benefit to grow, with the cost of this ���annuity��� being the savings you depleted. This makes sense and the strategy may work for those with a healthy amount of savings. But given the data on retirees��� reliance on Social Security and the sorry state of America���s retirement savings, is it practical?

Arguably, we look at delaying Social Security benefits the wrong way. It���s not that we add benefits by waiting. Rather, it���s that we lose less. In other words, we should think of the full retirement age as 70. If you claim earlier, how large a cut are you willing to suffer?

Here are five pointers:

Don���t go through your working life thinking Social Security will be enough for a comfortable retirement. Be sure to fund your 401(k) and IRA.

Have a contingency plan in case your Social Security benefit is smaller than you had hoped. What if you���re unable to work because, say, you suffer a disability or lose your job���and that means a more modest Social Security check? You should still be in good shape for retirement, provided you start saving in your 20s.

When in doubt, go for the larger Social Security benefit. Sketch out a strategy to meet this goal. That may involve working longer or following the Boston College approach.

Consider survivor benefits in your plans. Typically, a surviving spouse will receive the deceased worker���s full benefit���which is a big incentive for the family���s main breadwinner to delay claiming Social Security.

Investigate Social Security filing strategies several years before your planned retirement. As in all things to do with retirement, time is both your ally and your enemy.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include What Do You Mean,��Open Season��and��Straight Talk.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include What Do You Mean,��Open Season��and��Straight Talk.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy��reading articles by Dick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a��donation.

The post Staking Your Claim appeared first on HumbleDollar.