Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 296

March 4, 2021

Hierarchy of Savings

That notion came to mind recently when taking to a friend. She’s five years from retirement, concerned about today’s high stock market valuations and wondering if maxing out her 401(k) is her best choice. Would it be smarter, she wondered, to use her extra money to pay down consumer debt, pay ahead on her mortgage or make some home improvements? Here’s my take on the “hierarchy of savings”:

Emergency fund. I would make this a top priority. An annual Federal Reserve survey has found that 37% of U.S. families can’t handle an unexpected $400 expense. The pandemic’s economic fallout has highlighted how perilous that can be. My advice: Depending on how secure your job is, set aside between three and six months of living expenses in conservative investments as an emergency reserve.

High-interest debt. After you’ve established an emergency fund, it’s time to attack high-cost debt. For most of us, that means credit card balances. Even in today’s low-rate environment, credit cards charge an average 16%, according to Bankrate. Paying down high-interest debt is smart financially, plus it provides a great psychic win.

Employer retirement plans. There’s a host of tax-favored employment-based retirement plans, including for self-employed individuals. The standard financial guidance is to invest at least enough to capture any matching employer contribution. I recommend to my sons that they start with a minimum 10% of their income.

Health savings accounts. As I’ve written before, I’m a fan of health savings accounts, or HSAs. Used properly, they provide a triple tax savings—an initial tax deduction, tax-deferred growth and tax-free withdrawals if the money is used for qualifying medical expenses. Employers sometimes offer incentive contributions to an HSA, often coupled with a wellness program. To be eligible to fund an HSA, you need to enroll in a high-deductible health plan (HDHP). Such health insurance isn’t always offered to employees. If it is, I’ve found that a low-premium HDHP, coupled with an HSA, can be a cost-effective way to pay for health care.

Employer retirement plans (again). If you’ve tackled the items above and still have excess funds, maxing out your 401(k) or similar plan is a good way to go. If you fund a traditional retirement account, you can get an immediate tax deduction. For many, their withdrawals in retirement will be taxed at a lower rate than they’re paying today, which means the initial tax deduction more than pays for the eventual tax bill.

Roth IRA. Contributing to a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k) is a bet that your marginal tax rate today is lower than it will be in retirement. This bet can make particular sense for younger savers with relatively modest incomes. As you progress in your career and your salary increases, so will your marginal tax rate—at which point traditional, tax-deductible retirement accounts may be more appealing.

Many financial planners stress the notion of “tax diversity” in retirement. Having both traditional and Roth retirement accounts gives you the opportunity to better manage your annual retirement tax bill. Moreover, you don’t need to take required minimum distributions from a Roth IRA. Roth accounts also pass tax-free to your heirs.

College fund. Saving for your children’s college is a great thing to do. But it’s probably not your highest financial priority. Have you paid the monthly bills, paid off credit cards and saved for retirement? If you still have money left over, a 529 plan isn’t a bad way to go, because it offers tax-free growth if the money’s used for qualifying education expenses.

Mortgages. Paying off a mortgage early is a surprisingly controversial topic. The interest rate is an important consideration. Today’s historically low interest rates, and the increase in the standard deduction, make the tax benefit of mortgages less attractive than in years past. Many retirees love the idea of retiring debt-free, while some financial planners recommend continuing to carry mortgage debt and instead using extra cash for investment opportunities or as a reserve in case of emergencies.

Cash accounts. My wife and I became adults when Christmas Club and Vacation Club savings accounts were still a thing. My company had a credit union that made it easy to contribute to these accounts. In addition, my wife has always stressed saving for home maintenance and improvements. Yes, as a couple, we were fine examples of mental accounting.

We’ve now simplified our finances and have just a single money market account. The account is connected to a rewards credit card, which we use to pay for as many expenses as possible. Still, it’s hard to make a strong case for funding savings and money market accounts: We don’t earn a whole lot of interest.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. He enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609 and check out his earlier articles.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. He enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609 and check out his earlier articles.The post Hierarchy of Savings appeared first on HumbleDollar.

March 3, 2021

Standing Down

It would be hard to argue this was a smart financial decision. While defined benefit plans have mostly been replaced by defined contribution plans such as 401(k), 403(b) and 457 plans, the military still offers a pension. In fact, it’s arguably the gold standard of pensions, one that’s indexed to inflation and backed by Uncle Sam.

If you remain in military service for 20 years, your pension will amount to 50% of your highest 36 months of base pay. For each additional year of service beyond 20 years, that percentage increases by 2.5 percentage points. The plan is so good that Congress recently tweaked it to save costs. Those who join now only have access to the hybrid Blended Retirement System, which shifts some of the burden to save for retirement onto the individual.

The size of a military pension varies substantially, depending on rank and years of service. Given my active-duty career path, I estimate a 50% pension would have equaled roughly $58,000 per year in today’s dollars, plus I could have drawn that amount starting at age 45. Pensions for Reserve and National Guard servicemembers are far less generous, and hinge on the amount of time spent in uniform working on weekends, mobilized to assist during natural disasters, fighting in combat zones and so on.

My pension will depend on how actively I participate in the Reserves, but I conservatively estimate I’ll draw roughly 39% of my salary. That means I’ll receive some $42,300 a year once I turn age 60, or $15,700 less than if I’d stayed on active duty for another six years, plus that payout will start 15 years later.

The obvious question: Why forgo the comfort, security and immediacy of that pension money? There are many reasons I made the switch. But in the end, it boils down to this: Like everyone else I know in the military, I never joined for the money, and the drawbacks of continued service began to outweigh the positives. Over the past several years, I’ve been compiling a mental list of pros and cons. About a year or two ago, I noticed the cons were starting to win.

I won’t trouble readers with an exhaustive list, but I’ll highlight several issues that signaled it was time for a change. My family had lived in four places in two years. Moving and military life are, alas, synonymous with one another. When you have older kids, those moves get harder, as they repeatedly have to say goodbye to their friends. On top of that, my wife has a career of her own that she constantly interrupted to support my military service. Few outside the military are aware of how much spouses and kids sacrifice to support their servicemember’s career.

Another reason to leave active duty—something I never would have considered in my 20s: It’s been a humbling experience to watch my body begin to fail me. I’ve witnessed some senior leaders who expected their subordinates to perform physically at a level that they themselves could not. I felt uncomfortable knowing that, given the litany of injuries I’ve experienced, I was in danger of becoming that type of leader. The Reserves doesn’t have quite the same physical demands, and I’m grateful for that.

Finally, I looked at the opportunity cost both from a personal and career perspective. For those unfamiliar with the military, it can be a rewarding but isolating existence. The constant moving means you build wonderful friendships within the military but develop no roots in a local community.

I have many friends who continue serving on active duty because they love what they do, and I admire them for their conviction. While I’m grateful for the incredible opportunities I’ve had in uniform, including lifechanging experiences and opportunities to contribute in meaningful ways, I also realize that my ability to switch to civilian work—and have a career trajectory that I’d find meaningful—would get more difficult the longer I stayed in uniform and the older I got.

Forgoing the $870,000 in pension income I could have collected between ages 45 and 60, along with the $15,700 extra every year thereafter, might seem foolish to some. Indeed, I have a few family members and friends who have expressed incredulity at my decision.

Recognizing that I lack the benefit of 20 years or more of hindsight, which may indeed prove me a fool, I provide this insight into my decision-making process: Few of us would ever describe ourselves as a slave to money. Why then become a slave to a pension? If we intuitively know that the work we do is more important than the sum we’re paid for it, why do we use our prime working years to pursue a monetary objective, rather than one that’s professional or spiritual?

John Goodell is general counsel for the Texas Veterans Commission. He has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan, and check out his earlier articles.

John Goodell is general counsel for the Texas Veterans Commission. He has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan, and check out his earlier articles.The post Standing Down appeared first on HumbleDollar.

March 2, 2021

February’s Hits

Congress keeps changing the rules that govern retirement accounts and Social Security. James McGlynn looks at what's happened over the past half-a-dozen years—and what it means for retirees.

Want a happier retirement? Mike Drak looks back on the fallout from the pandemic—and spies eight lessons that can help us to be better prepared for retirement.

Buy aggressively when markets fall. All-time highs are a great time to invest. It’s tough to stick with what you know when emotions run high. Marc Bisbal Arias discusses the three lessons he learned in 2020.

Haven't yet cut the cord? For years, David Powell stuck with traditional satellite and cable TV—but the quality and cost savings of streaming services finally won him over.

Planning your post-pandemic travels? After spending three years traversing four continents, Mike Flack has a few pointers on how to save money on accommodation.

Retirees worry about "leaving money on the table," so they claim Social Security early, opt for lump sum pension payouts and avoid income annuities. But these strategies often backfire, says Rick Connor.

"So now what?" asks Mike Zaccardi. "I’m financially independent, passionate about investments and financial planning, love to write and present, and can devour steak. How to blend those?"

Meanwhile, the two most popular newsletters were Poor Old Me and Unhappy Results.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post February’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

March 1, 2021

Reflation Nation

RAMPANT SPECULATION in parts of the market has been obvious for months. Less obvious is whether investors collectively will pay a substantial price for it. Can a reflation trade end up piercing a market bubble?

Stocks posted solid gains in February—with the S&P 500 touching a record high on Feb. 12—but the final week felt a bit precarious, even if the benchmark ended the month down just 3.5% from that high. (Insert your favorite adjective to describe the correction so far: normal, frequent, healthy, necessary.)

But some investors appear concerned that a sharp spike in Treasury yields may be changing the market calculus. The 10-year yield hit its highest level in a year at 1.51% on Feb. 25. That’s just a touch below the S&P 500’s 1.53% dividend yield. The S&P’s earnings yield—the inverse of the price-earnings ratio—is now at its lowest level in three years versus the 10-year Treasury yield. Those two points matter because higher bond yields now offer greater competition for investor dollars.

While the iShares Core S&P 500 ETF (symbol: IVV) gained 2.8% in February, energy, leisure and financial shares surged double-digits. The Vanguard Energy ETF (VDE) jumped more than 22%. Indeed, commodity prices are red hot. Copper is up 20% year to date and has nearly doubled since its March 2020 low. Gold, however, has been left out. The SPDR Gold Shares ETF (GLD) fell more than 6% last month.

Small- and mid-cap value gained strongly in February, followed by microcaps, despite a sharp pullback for the latter in the final week. The iShares Micro-Cap ETF (IWC), up 65% over 12 months, gained more than 6% in February, even after factoring in a nearly 5% drop in the last week. The Vanguard Small-Cap Growth ETF (VBK) also fell 5%. Large-cap growth lagged value again, with the Vanguard Growth ETF gaining less than a percentage point last month. It’s now negative for the year, while the S&P is up 1.7%.

Last month, developed foreign country stocks nearly kept pace with the S&P 500, while emerging markets trailed. The Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF (VWO), up 32% for the past year, rose 1.6% for the month, restrained by the formerly hot Chinese market, which fell fractionally in February. The iShares MSCI China ETF (MCHI), up 42% over the past 12 months, dropped nearly 9% in February’s final week.

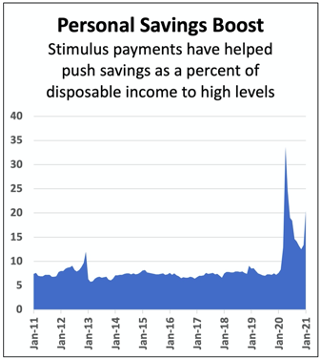

Fuel for the fire? The pandemic—fewer trips, fewer meals out and free stimulus cash from the federal government—has helped goose the personal savings rate, which measures savings as a percentage of disposable income. Though well off its May 2020 high, January's 20.5% rate remains far above earlier levels based on data going back to 1959, according to the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Fuel for the fire? The pandemic—fewer trips, fewer meals out and free stimulus cash from the federal government—has helped goose the personal savings rate, which measures savings as a percentage of disposable income. Though well off its May 2020 high, January's 20.5% rate remains far above earlier levels based on data going back to 1959, according to the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Some are saying speculation in stocks like retailer GameStop and movie-theater operator AMC is driven by bored investors flush with stimulus money. GameStop, as of Feb. 19 down more than 88% from its January high, bounced nearly 170% over the five trading days that followed.

Though tame compared to AMC and GameStop, shares in the leisure sector have also been on a wild ride. Stocks of many companies in the movie, cruise line, hotel and theme park business have soared on the notion they’ll benefit from pent-up demand once people feel safe to travel and crowd into fun places. The Invesco Dynamic Leisure and Entertainment ETF (PEJ) gained nearly 16% for the month and is up almost 31% in the past three months.

Does all that money sloshing around—plus more on the way—put a floor under the market, at least for now? Or did investors “buy the rumor” of vaccine availability, stimulus and economic recovery, while preparing to “sell the fact”? Time will tell.

Where have all the houses gone? Mortgage rates had ticked up from a record low of 2.65% on Jan. 7 to 2.97% as of Feb. 25. Coupled with a modest supply of homes for sale, it’s no wonder the S&P/Case-Shiller home price index is at a record high and well above its previous peak in 2006.

One sign of Americans' hunger to own their own home: The New York Times, citing Altos Research, reported on Feb. 26 that—compared to last winter—only about half as many homes are up for sale. Meanwhile, rents are falling and there’s a glut of empty apartments, the newspaper reported.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

The post Reflation Nation appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 28, 2021

Beware Groupthink

As the last 12 months have demonstrated, extreme and unexpected events can and do happen. But analysts whose job it is to make economic forecasts rarely go too far out on a limb. Sure, there are some forecasters who will take a chance with a view that’s far outside the consensus. But most don’t—and it’s for the reason Keynes cited. If you're a forecaster and you predict that tomorrow will be pretty much like today, that’s a safe bet. But if you forecast something wildly different, you’re more likely to be wrong. And if you are wrong, you’re more likely to look silly and put your career at risk.

As a result, forecasts tend to fall within a narrow range—one that, with the benefit of hindsight, ends up being far narrower than the range of what actually happens.

Consider an annual survey of Wall Street analysts. Barron’s asks experts from 10 prominent financial firms to share their market forecasts for the coming year. Just as Keynes would have predicted, these surveys exhibit a narrow clustering of opinions. For example, in December 2020, when Barron’s last polled its analysts, they predicted a total return for the S&P 500 of 10.3%—an estimate that’s squarely in line with the index's historical average of 10%. The headline in Barron’s read: “The Stock Market Could Gain Another 10% Next Year, Experts Say.” That’s like a weatherman in Honolulu predicting that it will be 80 and sunny.

There was some dispersion among the analysts’ opinions, but not much. The most optimistic analyst predicted a gain of about 19%. The most cautious predicted a gain of 2.5%. Notably, none of the analysts predicted a gain too far from the average, even though the stock market regularly delivers returns that vary widely from the average. In just the past 15 years, we’ve seen returns that exceeded 30% on two occasions (2013 and 2019), as well as a market drop of nearly 40% in 2008. In Keynes’s terms, none of these analysts wanted to risk their reputation by failing unconventionally.

The lesson I draw from this: Be careful of consensus thinking. It's seldom, if ever, a reliable guide to the future. Of course, this is not a new phenomenon. I mention it now, though, because it feels like today’s investment markets are in the grip of several particularly strong stories that have become the “consensus” view, with a range of opinions that's too narrow.

Bonds. Last year, when the Federal Reserve dropped its target interest rate to a range near zero, many investors abandoned bonds. The yields available simply became too meager. In addition—and maybe more important—investors began to worry that rates were more likely to rise than decline. This makes sense: With rates so close to zero, there just isn’t a lot of room to go lower. Because bonds generally lose value when rates rise, many have come to see the bond market as a lose-lose proposition.

That’s the widely shared view, but I wouldn’t be so quick to buy this argument. Yes, bonds can lose money. But when bonds lose money, especially if you stick with short- and intermediate-term issues, the losses are typically nowhere near as extreme as the losses that occur in the stock market. In fact, if you do the math, a slow, steady increase in rates is actually a good thing, on balance, for bond investors. Sure, you might lose a little value in the short term. But at a certain point, you’re better off because you can reinvest maturing bonds at higher rates. It’s for that reason that I still view bonds as a key pillar for most people’s portfolios.

Stocks. The stock market today, as represented by the S&P 500, is trading at 25 times estimated earnings. That compares to a long-term average of just under 17. It’s hard to look at these numbers and not conclude that the market is high. But the narrative that’s taken hold recently reminds me a little of the folktale The Emperor’s New Clothes. Here’s how the argument goes: The stock market might look like high, but it deserves this new elevated valuation for a good reason—lower interest rates.

According to the textbook formula for valuing a stock, there should be an inverse relationship between share prices and interest rates. When interest rates are lower, the present value of a company’s future profits rises and that means its share price should rise. With rates still so low, the collective belief is that the stock market has entered a new realm—one in which 25 times earnings should no longer be viewed as expensive. But again, I would urge caution in adopting this view. To be clear, I’m not predicting a market correction. But if there’s an opportunity to rebalance your account and take some profits, I wouldn’t hesitate. The market is not like an elevator that only goes up.

“Special” stocks. Over the past year, a new category of stocks seems to have emerged, led by companies that have benefitted disproportionately from the pandemic, including Zoom, Peloton and Teladoc. When I hear people talk about these stocks, I sometimes hear words like “untouchable.”

The list of “special” stocks also includes Tesla. I’ve seen Elon Musk referred to as “a god.” Sure, Tesla is great, but no investment should ever be viewed as infallible. That’s how we’ve gotten into trouble before. Remember that it's the marketers’ job to make you fall in love with a company. Your job as an investor is to remain strictly dispassionate.

Cash. Last year, a prominent hedge fund manager stated that “cash is trash.” Here’s how this argument goes: If banks are paying less than 1% on cash, while stocks are paying dividends of 1.5%, on average, why hold cash? That may sound convincing, but I wouldn’t buy it. Cash isn’t trash. It only looks that way when the stock market is going up.

As you think about your asset allocation, I wouldn’t get hung up on the fact that cash isn’t earning much. The purpose of cash, in my view, isn’t to make money. Its role is entirely different. Cash is there to help carry you through periods when the stock market is down, when your income is interrupted or when you have an unexpected expense. In all of those cases, you’ll be happy to have cash and won’t give a second thought to the rate it’s earning.

International markets. Over the past 10 years, an investment in the domestic stock market has returned more than 250%. Meanwhile, international markets have returned barely 60%. As a result, many have given up on international markets. Here’s how this argument goes: Look around the world and you’ll be hard pressed to find great companies like Apple, Amazon or Google anywhere else. That’s a testament to American ingenuity. Furthermore, many economies outside the U.S. are downright sluggish, with meager growth and declining populations. For these reasons, there’s no reason to diversify outside the U.S.

That’s the current narrative. But again, I would be careful. Yes, I think domestic investors should have most of their portfolio in domestic stocks. But historically, global stock markets have ebbed and flowed, and I don’t think we have entered some kind of new realm that will make U.S. stocks the permanently better choice.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, he advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, he advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Beware Groupthink appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 27, 2021

About the Kids

My wife and I have four children ages 45 to 50. They’re all married and, between them, have 13 children ages five to 17. They’re also all college graduates, with almost the entire cost paid by my wife and me. Three have master’s degrees. Arguably, we did our job when it comes to our children. They were given every opportunity.

Since graduating college, however, all four have had more employers than I did in 50 years. None has a pension. Only two have a 401(k), one with the employer match suspended. Raises have been scarce. One son works on commission.

Like many Americans, they’re caught in the crunch of saving for both their children’s college and their own retirement. They’ll have kids in college—some just starting college—when they reach retirement age. By contrast, I was age 55 when my youngest graduated college.

Here I sit with a pension, Social Security, no debt and investments I don’t plan to spend. Instead, those investments will be liquidated only if I predecease my wife and she needs the money or if there’s an extreme emergency, such as long-term-care expenses in excess of what our insurance will cover.

I’ve made it clear in the past that I’m big on reasonable frugality, living within your means, personal responsibility and so on. And yet I very much want to—and am planning to—leave as much money to my children as possible.

Is there any contradiction between my advocacy of personal responsibility and my determination to help my kids? There would be if I concluded my kids weren’t responsible individuals. But that isn’t the case. I don’t expect them to be exactly like me and I hesitate to hold them to my somewhat unique standards.

What if they violate my financial philosophy with the money we bequeath? I can’t do anything about that. But in any case, they won’t be receiving enough to become beach bums.

Admittedly, I occasionally cringe at how they spend money. It just isn’t what I would do. But they aren’t spendthrifts or, as far as I know, drowning in consumer debt. I have no reason to believe they’re financially irresponsible. I do know paying the bills, while saving for college and retirement, is a challenge for them.

My views on money were shaped by my parents, who grew up during the Depression of the 1930s. My parents were frugal, had no investments of any kind and what money they had was in a checking account. In retirement, they lived almost solely on Social Security.

My children grew up in a very different environment and society—one that’s more affluent and more consumption-oriented. That’s shaped their financial behavior. The fact that they’re married to people who also grew up in different environments and family structures also affects their money-related behavior. So be it.

Unless there comes a time when I see extreme irresponsibility, my goal of leaving them as much as possible will not change. What if I see irresponsibility in one or more of my children? I’ll leave their share of the inheritance to the grandchildren instead.

On a retirement planning forum, I asked, “Should financial planning include a strategy to help the kids and grandkids and, if so, how?” I wanted to know what people thought about having a well-defined strategy for bequeathing a significant sum, as opposed to leaving it to chance or aiming to spend the money yourself. I quickly learned how personal the issue was. Here’s a sampling of the comments I received:

“We gave all of our children a solid foundation and education opportunities. We're helping them now as we choose to. They're all doing well. We don't feel the need to pass savings on to them. It's not part of our goal.”

“I still remember that my grandmother left each of us grandkids $1,000 when she died. I was eight. I’m now 49. It just stuck with me that she thought of us and wanted to help us with college one day. I want to do the same for my kids and grandkids.”

“We set our two sons up for success in the way we raised them. We taught them that hard work will pay off. They both got an education in a field that pays well and now my youngest is 26 and earns what I make at 56 and our oldest son (30) earns more money than my wife and I combined.... No, we are not intentionally leaving a monetary legacy, but of course there should be a sizable sum left once we both pass.”

“I plan on enjoying my retirement and, if there's anything left, then my heirs will get something, but it's not a priority. It's their responsibility to live within their means and save for their own retirement.”

“My parents have made it a huge goal in life to leave a big inheritance to their children. Me? I have a disabled son who will always need a little help, so I factor that into my savings goals, but I also plan to enjoy my retirement and travel as much as possible. If there is anything left for the kids, well, then they'll be lucky!”

“I am watching my parents (age 60) spend themselves into the ground and cannot stop them. I am doing the right things (41, saving, no debt, etc.) and am trying to brace my household for supporting them within 10 years.”

“Our kids are still in school and start leaving next year for the military and college. We have plans to retire when the last one leaves. College is saved for and a few weddings are in our plan. My kids will have a firm foundation to build on and I don’t feel obligated to do anything more for them beyond helping them learn how to successfully plan their own financial future.”

“We want to leave the kids as much as we can. We paid the 20% down payment on a house for each of them. We also told them that we'd buy them their first new car. Our initial goal was to leave them at least $1 million each, and I'm sure we will leave them more than that.”

“If you die with an account balance, you, by definition, saved too much for retirement.”

The broad consensus among commenters: We aren’t planning to leave a legacy, but if there’s money left, that’s okay. In response to my question, a number of folks said they preferred to assist their adult children while they’re still alive:

“I’d rather help my children and grandchildren out while they really need it and while I am living rather than leaving a lot in savings.”

“Have you considered spending some of your money on experiences while you are still alive? Example would be a family vacation to an all-inclusive resort in the Caribbean. My parents did that for us and it created some great memories for all of us.”

“Why leave it to them when you die when you can give it to them while you’re living and watch them enjoy it?”

Like the commenters above, no doubt readers of this article will have different points of view. I suspect some will see this as a “first world problem,” because they’re struggling to amass enough for their own retirement. For me, I see it as an obligation owed to my family. Yes, my wife and I are fortunate to be able to help our kids. But I can’t think of many better ways to use our money.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

Protect human capital. Watch cashflow. Treat debt like a disease. Sanjib Saha details the three key steps that set him up for early retirement.

"Faced with a complicated world, we develop shorthand stories to quickly characterize investments," writes Adam Grossman. "Growing companies, for example, are 'going to the moon,' while struggling companies are 'doomed'.”

Got your emergency cash sitting in a savings account earning 0.5% a year or less? Kenyon Sayler makes the case for stashing those dollars in Series I savings bonds, where yields are currently 1.68%.

"Are SPACs the sort of thing the typical investor should buy?" asks James McGlynn. "Record amounts of SPAC money are chasing private companies, so there’s a real risk SPACs will end up overpaying for these companies."

If you buy and hold individual bonds, do you avoid interest rate risk? Rick Moberg tackles one of the most enduring investment myths.

"We get plausible information that seems to verify our outlook on life," writes Jim Wasserman. "This isn’t just a Fox News vs. MSNBC issue. It also crops up with 'can’t lose' investments and compelling market forecasts."

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, he was a compensation and benefits executive. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments and check out his earlier articles.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, he was a compensation and benefits executive. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments and check out his earlier articles.

The post About the Kids appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 26, 2021

Chews Wisely

No economist would ever tie an economic trend to any one factor, but the article proffered an interesting hypothesis. It suggested that, as more people looked at their iPhones while waiting in line at supermarkets, they were less prone to make spontaneous gum purchases at the checkout counter. Such sales are a substantial part of chewing gum sales.

I thought the connection might be the basis of an interesting article about how our time and attention are limited resources, and when we connect with one thing, we unwittingly disconnect from another. Few would lament disconnecting from chewing gum in favor of the iPhone. But what about giving up a tried-and-true investment for the latest hot one? Or how about neglecting family time to get “just one more task” done at work?

My gut saw the possible cause-and-effect connection. My heart liked the lesson that could be drawn from it. On top of all that, the article cited the generally reliable Euromonitor International as its data source.

But to quote Ronald Reagan, who was quoting the Russian proverb “doveryai, no proveryai,” it’s important to “trust, but verify.” A little digging revealed some flaws.

Aside from the probability of other contributing causes—such as the Great Recession making people cut out unnecessary purchases like chewing gum—it turns out that U.S. gum sales have been going up since the article was published, despite continued smartphone use. What’s more, there’s the issue of whether some gum chewers simply switched to a substitute good, like mints or candy. Who’s to say if people made fewer impulse purchases while looking at their iPhone or just felt like buying Tic Tacs instead?

So, that article went into the can. Still, I was left with a thought to chew on. (Had to offload that joke somehow.)

We live in an instant-access information age, perhaps too instant. We get seemingly plausible information delivered to our eyes that immediately resonates, rings true and seems to verify our outlook on life. No, this isn’t just a Fox News vs. MSNBC issue. It also crops up with “can’t lose” investments and compelling market forecasts. We get summaries that connect dots we didn’t know needed connecting. Sometimes the photograph or tale comes with citations we consider authoritative. Often the story appeals to our predisposition and we fall victim to confirmation bias. We then pass along the information as gospel truth.

If we’ve learned anything these past months, it’s that we should slow down before we become part of a chain of dubious data delivery. Of late, we’ve all heard a lot of secondhand stories. A “friend of a friend” will have made money in something with a “guaranteed high investment return.” We’re told that the government is going to close down an entire industry and we’d best get out of that market sector. The claims come with pseudo-statistics that compare apples and oranges (and leave bananas out completely).

In the online expat community, where I spend part of my time, people use social media to ask financial and legal questions about living abroad. They have no idea if the person supplying an authoritative-sounding answer is a financial analyst, a lawyer or a guy who grabbed the first thing that Google gave him. Still, the questioners take the information as fact and, worse still, pass it on to others.

We all need to get data healthy. Many already do this with food consumption, reading the labels on food packaging, asking exactly what “organic” means and dissecting how claims are hedged. (“Some studies indicate there may be a link with our product and the potential for a healthier heart.”) In the media literacy classes I used to teach to high schoolers, we’d laugh about how sugary, starchy breakfast cereals could be shown with juice and milk and then called part of a “good” breakfast. We need to do the same with the “good” data we’re offered.

If it makes no gut sense that Super Bowl wins by the AFC cause the stock market to go down, we shouldn’t buy the theory and, instead, assume it’s a coincidence. If someone shows you that shark attacks rise and fall every year commensurate with ice cream consumption, don’t blame Baskin-Robbins. Instead, consider that there might be an extraneous reason for both. Warm weather sends people both to the beach and in search of ice cream. Most important, don’t accept and blindly relay information because it has an air of “truthiness” to you. Make the idea earn your trust before you pass it on.

Which brings me to Trident gum. I dare say four out of five economists would recommend vigilance before using such data. And I never did find out why the fifth dentist wasn’t on board.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught economics and humanities for 20 years. Check out his previous articles. Jim is the author of Media, Marketing, and Me, about teaching behavioral economics and media literacy, as well as Summa, a children's story for multiracial, multi-ethnic and multicultural families. Jim lives in Spain with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at YourThirdLife.com.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught economics and humanities for 20 years. Check out his previous articles. Jim is the author of Media, Marketing, and Me, about teaching behavioral economics and media literacy, as well as Summa, a children's story for multiracial, multi-ethnic and multicultural families. Jim lives in Spain with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at YourThirdLife.com.The post Chews Wisely appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 25, 2021

Any Interest?

I’ve been thinking about that joke not because of the efficient markets theory, but because I’m amazed at how many smart people walk by a $100 bill every day. These folks have their emergency savings in an online bank, which right now might pay 0.5% interest. Many brick-and-mortar banks are paying one tenth that amount. Meanwhile, Series I savings bonds (don’t roll your eyes) are currently offering 1.68%. That’s an extra $118 in annual interest on a $10,000 emergency fund.

Friends will debate which exchange-traded fund is better based on a one basis point (0.01%) difference in fees. You’d need more than $1 million invested for one basis point to amount to $118—and yet could make that much extra simply by moving $10,000 from your online bank to an I savings bond.

For those not familiar with I bonds, they’re a type of U.S. savings bond that’s guaranteed to keep up with inflation. The Treasury Department introduced the I bond in 1998. When you buy one, you get a fixed rate that’s set for the life of the bonds. Currently, that fixed rate is zero, which doesn’t sound very appealing.

But on top of that fixed rate, you get inflation protection. To compensate for inflation, I bond holders receive a semi-annual interest rate that changes twice a year. Currently, it’s 0.84%. If you multiply that semi-annual interest rate by two and then add it to the fixed rate, you get the annual interest rate, which today is 1.68%. Like all Treasury instruments, I bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

The interest on I bonds is state tax-free. The interest can also be federal tax-free if you cash in the bond in the same year that you pay for higher education, though income restrictions apply.

What are the downsides? First, you have to hold an I bond for 12 months before you can redeem it, so you don’t want to invest all of your emergency savings right away and, instead, you should buy your I bonds gradually. If you redeem your bonds before five years have passed, you forfeit three months of interest.

Second, you’re limited in how much you can invest in I bonds. Each year, you’re allowed to directly purchase no more than $10,000 of I bonds. If you’re due a refund on your federal income taxes, you can also use that money to purchase an I bond, but only up to $5,000. The upshot: An individual can purchase $15,000 of I bonds per year, while a married couple is limited to $25,000, comprised of $10,000 each, plus up to $5,000 using their income tax refund.

The third issue isn’t really a downside, but rather something you have to get used to. Your broker can’t sell you I bonds. You can’t buy them on a secondary market. You can’t buy them from a bank (though your local bank may cash in your savings bonds for you). Instead, the only way to purchase I bonds are either with your tax refund or directly from the Treasury through TreasuryDirect.gov.

The website is user friendly. In about 10 minutes, you can set up an account, link it to a bank account and schedule the purchase of your first I bond. Result: You might spend 10 minutes and make $118 in extra interest.

Kenyon Sayler is a mechanical engineer at an international industrial firm. He and his wife Lisa are extraordinarily proud of their two adult sons. He enjoys walking his dog, traveling, reading and gardening. His previous article was Home Free.

Kenyon Sayler is a mechanical engineer at an international industrial firm. He and his wife Lisa are extraordinarily proud of their two adult sons. He enjoys walking his dog, traveling, reading and gardening. His previous article was Home Free.The post Any Interest? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 24, 2021

Certain but Risky

Proponents of this notion claim that if you buy a bond and interest rates rise—which they have this year—you won’t lose any principal because you’ll eventually get back the bond’s par value, assuming you hold the bond to maturity and the issuer doesn’t default. This is true, but it doesn’t mean individual bonds don’t involve interest rate risk. That myth rests on three faulty legs.

For starters, proponents conflate certainty of results with lack of interest rate risk. It’s undeniable that individual bonds deliver certainty if they’re held to maturity and issuers don’t default. Certainty, however, shouldn’t be confused with an absence of interest rate risk.

That brings me to proponents’ second mistake: They focus on principal and ignore interest. When market interest rates rise, you may get your principal back if you hold to maturity. But in the meantime, you forfeit the higher yields on offer elsewhere.

Let’s assume you purchase a new bond issue at its $1,000 par value. The bond has a 3% coupon and a 20-year maturity. The next day, market rates jump to 5%. The value of your bond would fall to $749 because it now yields $20 less per year than comparable bonds.

Over the next 20 years, you’d forfeit a total of $400 in interest on your $1,000 bond. Proponents can argue that forfeited interest doesn’t count as a loss. The bond market would respectfully disagree with you—and that disagreement is reflected in the lower price you’d get if you need to sell your bond.

What if you sold and reinvested the proceeds in a new bond with a 5% coupon and a comparable maturity date? Your return would be the same. Selling the bond to buy a higher-yielding bond has no economic benefit because the higher interest rate on the new bond would be offset by the capital loss on the old bond.

What’s the third mistake that proponents make? They muddy the role portfolio structure plays in determining interest rate risk. This gets a little complicated, but stay with me here.

Assume Jack builds a portfolio of individual municipal bonds and Diane buys a muni bond fund, both of which have seven-year average durations. After making their investments, interest rates increase by one percentage point, resulting in a 7% price decline. When they log into their respective brokerage accounts, Jack and Diane will see that their bonds are now valued at 93% of their cost. Proponents argue Jack can ignore his loss because it’s temporary, but Diane’s is permanent.

Is Jack really taking less risk? They’ve both incurred an equal unrealized loss and the yield on their portfolios would be identical from that point forward, assuming everything else is equal. In reality, everything else is rarely equal. Besides constantly changing interest rates, another important consideration is portfolio structure. That structure affects duration, which in turn affects interest rate risk.

Diane’s bond fund likely uses a rolling bond ladder structure, where the fund manager purchases bonds with maturity dates spaced out across multiple years. As the fund’s bonds mature, they’re replaced with new bonds that keep the overall portfolio’s duration relatively constant. If Jack also structures his portfolio this way, his results would be similar to Diane’s, assuming they maintain similar durations.

Alternatively, Jack may use a single maturity structure, where he purchases bonds that all mature about the same time. He might do this because he’s looking to fund a one-time expense, such as his daughter’s college costs. Or perhaps Jack has built a bond ladder structure where he purchases bonds with staggered maturity dates, so he has bonds maturing at regular intervals. As Jack’s bonds mature, they aren’t rolled into new bonds. Instead, he might use the proceeds to fund his annual retirement spending.

In these two structures, duration gradually declines until the last bond matures. If Jack used one of these two strategies, the interest rate risk in his portfolio would start off the same as Diane’s bond fund but would decline over time. Still, declining interest rate risk isn’t the same as no rate risk.

All this leads me to five conclusions. First, held-to-maturity individual bonds deliver certainty and are an effective way to fund known future expenses. Second, comparable bonds held in individual portfolios and bond funds have the same interest rate risk. Third, the interest rate risk in an individual portfolio and bond fund is likely to differ because of different portfolio structures. Fourth, while portfolios of individual bonds may have declining interest rate risk, that doesn’t mean they have no risk.

Finally, if you reject my conclusions—as I suspect some of you will—you can’t escape contingent interest rate risk. The no-interest-rate-risk myth requires buyers to hold to maturity. But what if life intervenes and you’re forced to sell your individual bonds before maturity? Despite your best intentions, you could lose money.

Rick Moberg is the retired chief financial officer of a publicly traded software company. He has an MBA in finance, is a CPA and has a passion for personal finance. Rick lives outside of Boston with his wife. Check out his previous articles.

Rick Moberg is the retired chief financial officer of a publicly traded software company. He has an MBA in finance, is a CPA and has a passion for personal finance. Rick lives outside of Boston with his wife. Check out his previous articles.The post Certain but Risky appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 23, 2021

What Went Right

This tip came from a close friend, when I told him about my money mistakes. My friend’s logic? Despite my missteps, I must have done a few things right to offset the damage.

He had a good point. There are three things I did that paved my path to financial freedom. The rest simply fell into place. These are not silver bullets and I’m not swearing to their universal usefulness. But they were powerful enough to save my day.

1. Protect my human capital. After earning my undergraduate degree, I started as a software engineer at a midsized company. I soon learned that a career in software development wasn’t about a fixed set of knowledge and expertise. Thanks to rapid technological change, skills can quickly become obsolete, as my first supervisor told me repeatedly. I’m forever grateful to him.

For better or worse, I never had big career ambitions. Folks like me run the risk of getting too comfortable in their job. But thanks to my first supervisor’s insistence on the need for continuous learning, I was able to safeguard my employability and ensure rising income throughout my career.

2. Watch my cashflow. My mother was the family accountant. Each month, my father would give her a fixed amount to cover all household expenses. She handled all spending and noted each purchase in a journal. She’d periodically balance the books and, when things didn’t add up, she’d spend hours spotting the discrepancies.

I adopted the same technique. On payday, I’d go to the bank and withdraw a fixed amount of cash. Like my mother, I used a cashbox to keep the money and a notebook to track my expenses. Result: My bank account grew each month with the leftover money and, with every pay hike, my savings rate rose.

This low-tech method, alas, stopped working as checks and plastic took over. I needed to adapt. I opened a separate checking account with overdraft protection to manage my cashflow. Each month, I moved a fixed amount from my “salary account” to this new checking account. All my expenses—cash withdrawals, checks, utilities, credit card payments—came from this account.

Was it boring to monitor my cashflow regularly? It certainly wasn’t as fun as watching Seinfeld, but it wasn’t too dreadful, either. Was it time consuming? Surprisingly, it took little time. Was it useful? You bet.

With an accurate sense of my spending and saving, I could easily predict the impact of any big financial decision. On top of that, the mentality instilled by a monthly allowance protected me from insidious lifestyle inflation. Yes, my spending went up over time, but every increase was a deliberate decision. Most important, I could apply the 80/20 rule to my money. A fixed spending allowance forced me to funnel funds from unimportant expenses to those I cared about. This was the key to a frugal, yet fulfilling life.

3. Treat debt like a disease. Growing up in a middle-class family in India, I developed a lifelong abhorrence of debt. At an early age, I felt horror when I heard stories of people losing everything to private lenders. I saw borrowing as a sign of desperate helplessness. I vowed to never sell my future for today’s enjoyment.

My inflexible attitude had some merits. I dodged the trap of overspending with credit cards and avoided becoming a “revolver.” I never paid a penny on car loans, instead only buying vehicles that I could afford to purchase with cash. I took out a mortgage for a modest townhome in the suburbs, but only because I expected to pay it off in three years and becoming a homeowner saved me hundreds of dollars in rent.

My insecurity about debt eased after my second marriage. My new family needed a bigger place in a neighborhood where my stepdaughter could attend a good public school. I faced the reality of home prices inflated by the housing bubble of the mid-2000s. I could no longer afford the luxury of a debt-free life. In my late 30s, I reluctantly signed up for a 30-year mortgage.

It was painful to watch thousands of dollars go toward mortgage payments each month. I kept chipping away at the principal with extra payments. I refinanced a few times to lower the interest rate. I felt better when the annual imputed rent—the money I would pay if I were renting the house instead of owning it—exceeded my annual housing cost minus the principal payments. When I paid off the mortgage before its tenth anniversary, I felt a heavy burden lift from my shoulders.

Ridding myself of the mortgage may have been more of a psychological relief than a smart financial move. Still, my cash outflow shrank sharply after the mortgage was gone. I realized that, from now on, I could survive on a much smaller paycheck. That seeded the idea of dialing down my working hours—and started me down the path to early retirement.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.The post What Went Right appeared first on HumbleDollar.