Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 292

April 11, 2021

It���s All in the Mix

The textbook method originated in the 1950s, with the work of a PhD student named Harry Markowitz. Up until that point, investors had mostly picked stocks and bonds in a vacuum, without giving much thought to how each individual investment might interact as part of a larger portfolio. In other words, the concept of diversification was not well understood and received little attention.

Even Benjamin Graham, who came before Markowitz and who���s considered the father of investment analysis, never talked about diversification in his work. For Graham, the question was always, ���Is this specific investment a good choice?��� It was never, ���What��combination��of investments should I choose?��� Then came Markowitz, who made the observation that the second question was at least as important as the first.

This is how Markowitz described it in an��early article: ���A portfolio with sixty different railway securities, for example, would not be as well diversified as the same size portfolio with some railroad, some public utility, mining, various sorts of manufacturing, etc. The reason is that it is generally more likely for firms within the same industry to do poorly at the same time than for firms in dissimilar industries.���

In other words, if you���re trying to build a diversified portfolio, you need to do more than simply buy a collection of assets. Instead, you need to buy a collection of assets that you expect to behave differently from one another���in statistics talk, to exhibit low correlations with one another. While this might seem obvious today, it wasn���t obvious in 1952 when Markowitz published his first paper. His work was so new, in fact, that it came to be known���and is still known���as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT).

The��mathematical details��are dense, but the promise of MPT was appealing. You may have heard the term ���efficient frontier.��� This was Markowitz���s invention, and it lies at the heart of his framework. In simple terms, the efficient frontier offers investors a menu of ���efficient������or optimal���portfolios to choose from. Each portfolio is optimal because it offers either the maximum potential return for a given level of risk, or the minimum amount of risk for a given level of return.

Suppose, for example, your goal is to earn 5% annual returns. You could simply locate that point on the efficient frontier, and it would tell you how to construct a portfolio geared to that goal. Prefer 7% returns or maybe 10%? Those options, along with others, could all be found on the efficient frontier.

The efficient frontier can be used to build a portfolio of stocks, as Markowitz illustrated in his initial work. It can also be used���and today is more commonly used���to build portfolios that combine multiple asset classes. Suppose, for example, you wanted to build a portfolio combining stocks, bonds and real estate. An efficient frontier could provide you with the optimal combinations of those asset classes���or any others. For this reason, MPT seems ideal.

But here���s the problem: It���s a little too good to be true. To build an efficient frontier requires that you have data about the future���and not just a little bit of data, but a lot. Here���s the data you need for each asset class:

Expected annual return

Expected standard deviation, a measure of the year-to-year variability of returns

Expected correlations among all of the asset classes included in the analysis

All of this data is readily available on a historical basis, of course. But it���s impossible to predict going forward. William Bernstein, writing in his book��The Intelligent Asset Allocator, described the problem this way: ���It���s a little like trying to generate electrical power by placing a battery and a lightning rod at the last place you saw lightning strike. It isn���t likely to strike there again.���

As Bernstein notes, ���Next year���s efficient frontier will be nowhere near last year���s.��� To illustrate, he cites Japan���s stock market, which��peaked��in 1989 and still���more than 30 years later���hasn���t fully recovered. If you had built an efficient frontier using data prior to 1989, it would have recommended a hefty allocation to Japan. But data since 1989 would recommend the opposite. In short, Modern Portfolio Theory, as appealing as it sounds in theory, is difficult to implement in practice.

That said, Markowitz���s fundamental insight���for which he won a��Nobel Prize���does carry a key lesson for every investor: Correlations are paramount. I can���t tell you when or if the stock market will see a correction. But the good news is, you don���t need to worry about building a strictly optimal portfolio, in the textbook sense, to protect yourself. You just need a sensible mix of stocks, bonds and other asset classes that aren���t tightly correlated. As you think about your portfolio and the risk posed by today's stock prices, this is, I think, the most important thing.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free��e-books, he advocates an evidence-based��approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free��e-books, he advocates an evidence-based��approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.The post It���s All in the Mix appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 10, 2021

Feel Better

I doubt Buffett feels bad about this. Is your surname neither Simons nor Bezos? I don���t think you should feel bad, either.

Money can be maddening���if we let it. There will almost always be some parts of our portfolio whose performance disappoints. There will always be some folks who are wealthier. But whether it���s our investment performance or our overall net worth, we shouldn���t let ourselves be bothered by our relative standing. Why not? Here are five reasons.

1. We likely made more good decisions than bad. Just 52.6% of American households own stocks, according to the Federal Reserve. If you count yourself among that group, your investment performance has almost certainly been better than that of the stock-less 47.4%.

What���s your net worth���the value of your assets, including your home, minus all debt? If it���s greater $122,000, you���re wealthier than half of all U.S. households. Yes, all of us throw the occasional pity-party for ourselves. But the fact is, if you���re reading this article, you are likely in far better financial shape than most of your fellow citizens.

2. What���s valued economically changes. Those who have been paying attention will remember me telling this story before: When my father graduated from Cambridge University in 1956, he took the highest-paying job on offer, which was ��800 a year working as a reporter for the Financial Times. That was ��100 more than he could have made as a management trainee for Royal Dutch Shell, which was the next highest-paying job he was offered.

By contrast, when I graduated Cambridge in 1985, my starting salary as a junior reporter was ��6,500, less than half what my university friends earned by joining financial firms in the City of London. For today���s would-be journalists, the wage disparity is likely to be even greater. My point: The price that the economy puts on particular skills changes over time.

If we have a set of talents that aren���t particularly well-rewarded by today���s economy, we could try a different career and perhaps that���ll prove necessary. Still, pursuing a high-paying career for which we���re ill-suited is likely to be a miserable endeavor���and probably an unsuccessful one.

3. Don���t overlook the role of luck. With good savings habits and a little financial savvy, I think almost anybody can amass at least a modest nest egg. But we all know people who have done far better. Oftentimes, they appear to have lucked out, whether it���s because they have wealthy parents, a high-earning spouse, a single lucky stock pick, or a boss who takes a shine to them and pulls them up the corporate ladder.

I can tell you how to improve your chances of financial success, but I can���t tell you how to improve your luck. Still, here���s a suggestion: Spend a little time thinking about why others might view you as lucky. All of us get the occasional lucky break. We might view our good fortune as well-deserved���but others might see it otherwise.

4. We usually don���t know how others are truly doing. People often lie about their investment performance or they simply don���t know the truth. They boast about their winning investments, but conveniently forget to mention their losers, especially those that have been sold. They���ll talk about how much their portfolio has grown, but neglect to factor in all the new savings they���ve added. They���ll tout their market-beating returns but fail to note that the risk involved was far greater than that of a broad market index.

Similarly, people often try to give off an air of being more financially prosperous than they really are. Such signaling may make them feel good. But it also leaves them poorer, because it inevitably involves buying high-priced goods to impress those around them. We may instinctively assume that the appearance of affluence is the same as affluence, but in truth the former is the mortal enemy of the latter.

5. We may have less���but that doesn���t mean we aren���t happier. As recent research makes clear, money can indeed buy happiness. But I also believe that happiness can be bolstered by good health, a great night���s sleep, helping others, a fun evening with friends and a whole host of other factors.

So why do we focus on income and wealth as a proxy for happiness? Money is easily measured and���if we confuse affluence with the appearance of affluence���easily observed. By contrast, it���s often hard to gauge the state of the neighbors��� marriage, or their physical and mental health, or whether what they do each day seems meaningful to them. Yet these are almost certainly more important to their happiness than the size of their bank balance.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

Mike Drak says there are three types of retiree. "What type are you?" he asks. "If you can answer that question, you���ve taken a crucial step toward a happier retirement."

Phil Dawson's 92-year-old mother fell down the stairs in late 2019. Planning to use Medicaid to pay nursing home costs? You need to read Phil's story.

���While I���ve learned to be more risk��tolerant, my mindset is still one which favors safety,��� says Kristine Hayes. ���Wild stock fluctuations are easier to stomach knowing I can rely on one account to slowly keep increasing.���

As we manage our financial life, some amount of forecasting is unavoidable. Adam Grossman offers three pitfalls to watch out for���and five tips for avoiding them.

What caught the attention of HumbleDollar's readers last month? Check out the seven most popular articles.

"The pension crisis will have an enormous impact on the future of our children and grandchildren," writes Tom Sedoric. "I predict a swiftly rising tide of taxes and suggest you plan accordingly."

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.The post Feel Better appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 9, 2021

A Firm Foundation

After a few years, I left that job to take a higher-paying position, but not before I became fully vested in the pension. Even as a 20-something-year-old, with no basic understanding of investment principles, I knew I���d likely never find another retirement asset as valuable as that pension plan.

Just after I turned 30, I was hired as a departmental manager at a small private college���a job I���ve been at for 23 years now. Similar to my first job, the salary I���m paid isn���t overly generous, but the retirement benefits are.

What does differ between the two jobs is the control I have over my retirement accounts. With my pension plan, there are no decisions for me to make regarding how my money is invested. When it comes time to withdraw the money, the only choice I���ll have is whether to take the pension as a lump sum or as lifetime monthly income. By contrast, with my current employer���s plan, I���m in total control. I decide how much of my own money to invest. I decide how the money my employer contributes is invested. And, ultimately, I���ll need to decide how best to draw the funds out.

It probably isn���t surprising that, when I first began working at the college, I chose to invest my retirement contributions conservatively. Faced with an overwhelming number of investment options and having no basic understanding of mutual funds, I picked an account with the phrase ���guaranteed return��� in the description. On paper, it appeared to be the account most closely resembling the pension plan from my first job.

After working at the college for a few years, I met with an advisor from TIAA, the financial firm that manages the college���s retirement plans. The advisor suggested that, at age 34, I was invested far too conservatively. While I wasn���t keen on risking my money in the stock market, we eventually arrived at a compromise. I���d invest my future contributions in a few stock mutual funds, but leave the money I���d already accumulated in the guaranteed account.

Over the next 20 years, I gained more knowledge about investing and retirement accounts. As I learned more, I questioned my decision to keep money in a low-yield guaranteed account. I became more concerned when I figured out that account was, in essence, designed to function as an annuity. Most everything I���d read about annuities was negative. I worried I���d made a huge mistake by choosing to invest in a product some people seemed to view as the equivalent of throwing money away.

These days, I fret less about my decision.

While I���ve learned to be more risk tolerant over the past three decades, my primary mindset is still one which favors safety and stability. During the Great Recession, I was comforted that my guaranteed account kept growing, while my other accounts plunged in value. Wild stock market fluctuations are easier for me to stomach knowing I can rely on one account to slowly and steadily keep increasing.

I���ve also learned more details about my guaranteed-earnings account. I���ll have a number of choices when drawing my money out, including the option of taking interest-only payments before eventually annuitizing the funds. Having the flexibility to take interest payments during the first few years of my retirement should allow me to delay tapping my pension plan and other investment accounts. If I eventually choose to switch to monthly payouts, my annuity���in conjunction with Social Security and my pension���should provide me with enough money to cover my fixed living expenses well into old age.

I���ve also discovered that being a long-term investor in the guaranteed account comes with an added bonus: The rates of return credited to the account are structured in a way that long-term investors receive higher rates of return, and higher monthly payouts, compared to investors who make all of their contributions to the account just prior to drawing their money out.

All that said, I would no doubt have done far better over the past 23 years if I���d invested heavily in stock funds from the beginning, rather than putting so much into the guaranteed account. But without that guaranteed account, I���m not sure I would���ve ever had the nerve to put any money into stocks.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. She��enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs. Check out Kristine's earlier articles.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. She��enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs. Check out Kristine's earlier articles.The post A Firm Foundation appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 8, 2021

Who Are You?

That might sound difficult, but it isn���t. To help get you started, here are the three general types of retiree I discovered during my research on retirement:

1. Comfort-oriented retirees. These folks like to avoid stress, instead favoring a safe, predictable retirement. They no longer have any goals. Retiring was their big goal and, now that it���s behind them, they just want to rest and take it easy. Comfort-oriented retirees don���t need much to be happy. Just the basics will do: food on the table, a roof over their head and some level of financial security.

My mother was a comfort-oriented retiree. She lived a simple life and, after my father passed away, was content to help family members, take care of her cat Boots and enjoy time with friends. She never felt the need to run a marathon or travel the world. She was happy with how things were and wasn���t inclined to take risks that might bring discomfort.

2. Growth-oriented retirees. These retirees have a need to keep stretching, exploring, learning and experiencing new things. If they can���t do that, they aren���t happy. They���ve created a bucket list a mile long and plan on knocking things off that list for as long as they can. They have a hardwired desire to feel ���significant��� and a need for accomplishment and contribution.

Their work nourished these needs, and they lost that source of nourishment when they retired. Until they can find a way of replacing it, they���ll always feel like something is missing in their life.

Abraham Maslow, the creator of the famous ���hierarchy of needs,��� called individuals like this ���self-actualizers.��� They have a constant need for personal growth and an insatiable hunger to realize their potential, and thereby become everything that they can be. They can accomplish this through many means, including succeeding athletically, creating art or starting their own business.

Self-actualizers, even retired ones, are never satisfied with how things are. They���re continually setting new personal goals that will challenge and improve them, so they can realize their full retirement potential.

3. Self-transcenders. Near the end of his life, Maslow was in the process of amending his model to include a higher level of psychological development���even higher than self-actualization���which he called ���self-transcendence.���

Self-transcenders look for a cause, a need, a problem to be solved, something that they���re passionate about. This becomes their mission. They know it isn���t��how much you give that counts, but rather��how much love you put into the giving. Helping those who are struggling leads to the ���helper���s high,��� a feeling of intense joy, peace and well-being.

Helping others gives self-transcenders a strong sense of purpose. When they have what they consider a purpose-driven retirement, they���re happier. They can sleep peacefully at night knowing that they did something to help others. They wake up in the morning feeling excited and wondering, ���Who can I help today?���

Now ask yourself: What type of retiree are you? If you can answer that question, you���ve taken a crucial step toward a happier retirement.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He���s the author of

Retirement Heaven or Hell

, which was just published, as well as an earlier book,

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to��

BoomingEncore.com

. His previous article was Retirement Preview.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He���s the author of

Retirement Heaven or Hell

, which was just published, as well as an earlier book,

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to��

BoomingEncore.com

. His previous article was Retirement Preview.The post Who Are You? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 7, 2021

Caring for Mom

Before her fall, we had a tenuous but semi-functional system of care in place. But the chaotic aftermath plunged us into unknown territory and claimed incalculable amounts of time, money and other resources from her caregivers. We spent months struggling with a new, impossibly complex set of rules and referees.

A few short weeks after her accident, Mom���s rehab benefits approached exhaustion and we were summarily advised of her approaching discharge date of Dec. 21. She had regained a fraction of her cognition and mobility but was clearly unable to manage her own day-to-day needs at home.

A moment of choice had arrived. Medicaid rules required that she enter a long-term-care (LTC) facility directly from inpatient rehabilitation. If we took her home, even for a day, she would need to experience another health crisis and inpatient stay before she would again be eligible for LTC benefits. We���her children���agreed that it was time for LTC.

You need to be all but broke to get Medicaid assistance, at least in Maryland. My mom was receiving a small railroad pension, which covered about 85% of her living expenses prior to her accident. The rest hinged on kids and grandkids, who had for many years kept her afloat with careful attention to her needs and expenses. But that pension���and even her small life insurance policy with a tiny cash value���became a target when we applied for Medicaid benefits.

The pace of the Medicaid system is incomprehensibly slow. While Mom���s state benefits were applied for and under review, she was accruing costs of about $400 per day in professional care and housing. A number of her kids scrambled to cover these expenses, along with the costs associated with filing for state benefits using the required 17-page application. The three filing options, listed in order of increasing expense and probability of success, are:

Do it yourself

Hire a Medicaid application specialist

Hire an attorney

Given the urgency of our situation, we chose the third option, with an engagement agreement dated Dec. 9, 2019. The hat was passed among the family, and those who could contribute to the endeavor were generous.

A Medicaid applicant has to submit an extraordinary amount of data. Thankfully, Mom���s financial life was simple and I���d been carefully filing away the relevant documents for years. Still, gathering the requested items took dozens of hours over a period of weeks. Finally, the application was filed on Jan. 8, 2020.

While waiting for Medicaid approval, Mom���s medical expenses continued to accrue. For us, there was a provision known as PEME, short for pre-eligibility medical expense, that covers costs incurred after the date of application but before the date of approval. To be eligible, these expenses must be outstanding at the time of approval, meaning many of them would be well overdue prior to Medicaid coverage. As demands for payment became more urgent and threatening, I resisted the urge to simply pay them in an effort to reduce the noise in my head. This turned out to be the right financial decision.

On Jan. 10, I received a notice of ���Request for Information to Verify Eligibility��� from the Medicaid case manager. The request was for Form DHMH 257, or ���Long Term Care Activity Report,��� from Mom���s LTC facility. It���s essentially a detailed summary of the services she was receiving day-to-day, establishing her condition and need for professional care. This form must be provided by the care facility directly to the Medicaid case manager.

We forwarded the notice to multiple administrators at the facility, first by email and then in person. None of our emails or phone messages received responses over the ensuing six weeks. There���s apparently no incentive for the facility to produce the form, as the folks there are pleased to continue to charge the patient for services provided. We received a notice of ineligibility from Medicaid on Feb. 25, 2020, because the requested information hadn���t been provided. Mom���s attorney stepped in with some very specific demands and threats, and eventually the proper form was produced. This may have been the most valuable service that the attorney provided.

Notice of eligibility was finally received on March 13, more than 60 days after the application was filed. I finally slept through the night for the first time in weeks.

Institutional LTC is imperfect. This is a very generous statement. The staff members at the facility were mostly polite and competent, but significant medical mistakes were made and needed care wasn���t always provided in a timely manner. My daughter Leah, who was employed at a respected LTC facility for years, helped the family to square its expectations with reality. We learned that even better facilities are understaffed, plus the staff is typically underpaid. Fortunately, Mom had visits from family members every day without fail. We were able to fill in the gaps in service and advocate for Mom when care was slow. This was not the case for all residents, some of whom saw no visitors for days or weeks on end.

Then COVID-19 hit. Mom���s daily visitors went from early and often to zero. In four short months, she had gone from ruling the universe from a recliner in her home to helpless dependence on overworked strangers. She was not pleased with this arrangement and aired her objections to anyone who would listen. This increased the emotional load on her already distressed family. Her 93rd birthday was celebrated on May 5, with her masked family on the opposite side of an exterior window.

While our family was struggling to understand and adapt to the chaos that engulfed us, Mom���s assiduous great-grandson Brooks discovered a recent, little known change in Medicaid options. This change provided an opportunity to transfer a portion of her benefits to home-based care while still maintaining full eligibility. This had clear advantages for Mom and for the state, but meant much of her increased day-to-day care would fall back on the family. Brooks carefully navigated yet another complex application process. Some gracious volunteers worked out the details, and Mom returned home on July 31. Home-based care is now provided 24/7, mostly by unpaid family members. Professional care is available for a few hours each week to help with the heavy lifting. Mom is glad to be home and the costs to the state are much reduced.

It pays to make friends before you need them. Care for our aging mom, in her aging home, has fallen disproportionately on a small fraction of her large family. It isn���t clear how long we can continue to provide the needed care, or how those needs will change, or when this part of the story will end. Could my parents have predicted and prepared for this situation? I don���t know. But my humble suggestion is this: Strengthen yourself and your family���your human capital���in preparation for challenges you can���t yet imagine.

When not paddling, biking or shooting, Phil Dawson provides technical services for a global auto manufacturer. He, his sweetheart Donna and their four extraordinary daughters live in and around Jarrettsville, Maryland.��You can contact Phil via

LinkedIn

.��Check out his earlier articles.

When not paddling, biking or shooting, Phil Dawson provides technical services for a global auto manufacturer. He, his sweetheart Donna and their four extraordinary daughters live in and around Jarrettsville, Maryland.��You can contact Phil via

LinkedIn

.��Check out his earlier articles.The post Caring for Mom appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 6, 2021

Kick the Can

The councilors in Portsmouth aren���t alone. The shock waves are shared by towns, cities, counties and states countrywide as they come to terms with the true depth of the pension crisis. In its 2020 report, the pension reform organization Equable noted, ���While a few statewide pension plans recovered from the Great Recession,��the majority of retirement systems have entered this next recession in a weaker position than they were going into the last recession.��� Further, only five states���Idaho, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington and Wisconsin���had funded at least 90% of their pension plans.

There���s a number of reasons we face this crisis. During flush economic times, when we enjoyed annual double-digit stock market returns and moderate inflation, it was easy for officials at all levels of government to be generous with increased benefits for police officers, firefighters, teachers and public workers. It was also easy for the public not to take notice as we kicked the proverbial can down the road.

A mid-2020 report by Pew Charitable Trust revealed that the 50-state $1.24 trillion pension funding shortfall between assets and future liabilities had improved slightly through 2018 after a decade of slow recovery from the 2008-09 economic crisis. As the pandemic took hold of our health systems and the economy, the report warned the gap would increase dramatically���by more than $500 billion.

The pension crisis is apolitical, impacting blue and red states with equal fiscal ferocity���and it isn't going away. ���We have a demographic crisis and that���s showing up in the nation���s retirement systems,��� said William Glasgall, a senior vice president at The Volcker Alliance, an organization dedicated to good governance at all levels. ���They neglected to fund them properly.���

It���s easy to blame local and state officials, along with public pension fund managers, for bad deals and risky investments. Yet when faced with a fiscal crisis, we as individual citizens and taxpayers need to look in the mirror and ask what we could have done to mitigate the crisis.

True, we can���t rewrite the past, but we can ask hard questions and do much better as citizens going forward. We can expand our civic duty and hold local officials accountable and question their due diligence when taxing and spending decisions are made. No one begrudges pensions for our public servants, but no one is well served by ignoring the potential fiscal blowback of ever-escalating liabilities.

The pension crisis is but one debt obligation being kicked down the road that will have an enormous impact on the future of our children and grandchildren. Other cans being kicked down the road are Social Security, Medicare, other entitlements and the overall federal deficit.

Many public workers have a pension, a union and a contract. But who represents the other taxpayers in this formula? I predict a swiftly rising tide of taxes and suggest you plan accordingly.

Tom Sedoric is executive managing director of the

Sedoric Group

, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. A Wisconsin native, he loves being on the water, knows some amazing card tricks and can fix just about anything. Tom's previous article was A Combustible Mix.

Tom Sedoric is executive managing director of the

Sedoric Group

, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. A Wisconsin native, he loves being on the water, knows some amazing card tricks and can fix just about anything. Tom's previous article was A Combustible Mix.The post Kick the Can appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 5, 2021

March’s Hits

Planning a post-pandemic spending spree? So is Dennis Friedman���but, even though he's retired, he's not worried about running out of money.

"You don���t truly know someone until you���ve seen his or her tax return," plus 11 other financial planning truths, courtesy of the always insightful Adam Grossman.

Confident that U.S. stocks are in a bubble? Next comes the hard part, says Adam Grossman: figuring out what to do.

Should you fund the 401(k), prepay the mortgage, build up an emergency fund or stash your dollars elsewhere? Rick Connor offers his take on the hierarchy of savings.

When he turns age 70 later this year, Dennis Friedman will claim Social Security, the final piece of his retirement puzzle. Here are the five questions he asked as he wrapped up his planning.

At age 33, Mike Zaccardi is financially independent, thanks in part to saving 90% of his post-tax income in recent years. Mike's response: "Big whoop."

What happens if you rely on the car rental insurance offered by your credit card���and you have an accident? Mike Flack found out.

What about our weekly newsletters? March's most popular were Nine Roads to Ruin and Blowing Bubbles. Meanwhile, the site's new Voices section has garnered a healthy audience, but the vast majority of folks, alas, read but don't comment. The question that, so far, has intrigued readers the most: What purchase do you most regret?

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.The post March’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 4, 2021

Three Landmines

This is funny but, for the most part, I agree. It’s especially true in the world of investments. And yet, as you manage your financial life, some amount of forecasting is unavoidable. Anyone trying to build a retirement plan, for example, has to think about future market returns, interest rates, inflation and taxes. All of these factors—and others—will have an enormous impact on our financial future, so we need to make some estimates.

If forecasting is a necessary evil, it’s important to understand it—flaws and all. Daniel Kahneman, a founding father of behavioral finance, provides a useful framework. The first thing to understand about forecasts, he says, is that there are three factors that can cause them to go awry: incorrect or incomplete information, biases and noise.

1. Information. This one might seem self-explanatory. After all, the fundamental problem with any prediction is that it’s impossible to know what will happen in the future. That seems obvious. But for investors, it isn’t so simple. The reality is, there’s a lot of information that could help us make predictions. But sometimes that information is flawed, incomplete or irrelevant. As an example, you may recall the 1983 movie Trading Places.

In that film, a group of investors was betting on commodities—specifically, frozen orange juice. The prevailing wisdom was that a cold winter had hurt the orange harvest and would result in higher orange prices that year. But in the end, it turned out that the cold weather hadn’t had much of an impact. The harvest was fine and prices moved in the opposite direction from most investors’ expectations. In other words, investors were right about the weather but lacked information on the harvest itself. They only had one piece of the puzzle. To be sure, this is a fictional example, but this kind of thing happens all the time. As an investor, you need information that’s both reliable and complete.

We saw the same sort of effect in 2020. When the coronavirus shut down the economy, it was clear it would impact corporate earnings and thus stock prices. But no one knew precisely how things would turn out—which companies would be hurt, which would benefit and how long it would last. Again, we had a lot of information, but still there were a lot of holes.

2. Biases. When we talk about errors in investment forecasting, what we’re usually talking about are biases. When we lack information, that's a problem that is largely out of our control. But biases are problems we cause ourselves. Biases refer to the way we use the information we have. Even in situations with perfect information, biases cause people to interpret that information differently or to cherry pick the information they wish to include.

We see investor biases around presidential elections, for example. Each candidate’s platform is usually pretty clear. Where investors differ, however, is in how they expect those policies to affect markets.

Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow discusses biases—including investing biases—in detail. It’s a book I recommend.

3. Noise. In behavioral finance, biases get most of the attention. But Kahneman believes noise is an underrated contributor to investment forecasting. What is noise exactly? In short, it’s randomness in human thinking and behavior. Whereas biases have a logical basis—even if that basis is flawed—noise has no underlying logic at all. In Kahneman’s research, he’s found a surprising amount of noise in the world. Professionals as diverse as physicians, insurance adjusters and software developers all exhibit noise in their work.

What does it mean to exhibit noise? As an example, Kahneman cites pathologists making two assessments of the same biopsy. The correlation between two assessments by the same pathologist was, on average, just 60%. In other words, the same pathologist looking at the same data came to a different conclusion 40% of the time—for no clear reason.

Kahneman found the same thing across other professions and industries, including finance. “The problem,” Kahneman explains, “is that humans are unreliable decision makers; their judgments are strongly influenced by irrelevant factors, such as their current mood, the time since their last meal, and the weather.”

As an investor, how can you protect yourself—and your finances—from the landmines of bad information, bias and noise? Drawing on Kahneman’s work, as well as that of Philip Tetlock, co-author of Superforecasting , here are five recommendations:

Consider the forecaster’s track record. Just because you see pundits speaking on TV or quoted in the news doesn’t mean that their track record has been vetted. If they have a public platform, their track record should be public as well, allowing you to judge it for yourself.

Evaluate a forecaster’s methodology. Is he or she relying on facts and data or on intuition and stories? Is the forecast based on simple extrapolation or is there a more logical basis? Again, don’t assume that everyone with a public platform is doing things logically.

Consult multiple sources. Don’t rely on just one forecast. This can help lessen the impact of noise. As Kahneman noted, people’s views are often inconsistent with their own prior judgments, so judgments will certainly differ from person to person.

To the extent possible, structure your portfolio to be “all weather,” so you’ll be okay regardless of how the future turns out. In other words, don’t set your finances up to be overly wedded to—and thus overly exposed to—one particular version of the future. That will give you the freedom to largely ignore the constant din of investment narrative coming out of Wall Street.

Try to remove judgment from your investment process whenever possible. I always recommend a written investment policy, for example, including a target asset allocation and rules for rebalancing.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, he advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, he advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Three Landmines appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 3, 2021

Risk Less Make More

Want to make wiser portfolio choices? Keep these nine notions in mind:

1. Bad results happen to good investors. Let’s start with one of the most counterintuitive notions in investing: Just because we score spectacular short-term gains doesn’t mean we made smart decisions—and just because our portfolio struggles in the short run doesn’t mean we got it badly wrong. Indeed, spectacular short-term results are almost always a sign of idiotic investing rewarded by dumb luck.

2. The possibilities are endless. We have just one past, but we face all kinds of possible futures—and we don’t know which one we’ll get. Or, to put it another way, more things can happen than will happen. If we roll the dice and bet big on one part of the financial markets, we’re ignoring a host of other possible scenarios and our overconfidence may come back to haunt us. That, in a nutshell, is why it’s prudent to diversify.

3. Good odds aren’t everything. If history is any guide, the stock market should post gains in three years out of four. Those are pretty good odds. But what if this isn’t one of those years—and stocks come crashing down? We need to consider not just probabilities, but also consequences.

For instance, number-crunching investment experts will argue that, if we have a lump sum earmarked for stocks, we should invest it right away, because the odds suggest we’ll do far better than if we spoon the money into the market. But such advice is reckless—unless we also ask about consequences. If my financial future hinges on a $1 million inheritance that I’m looking to invest, and I’ll be ruined if I dump it all in stocks and the market immediately crashes, then playing the probabilities is the height of foolishness—and, instead, I should reduce risk by easing slowly into stocks.

4. Aiming to win means we’re likely to lose. I suspect almost every reader of HumbleDollar understands the logic behind indexing: Before costs, investors collectively earn the market averages. After costs, investors—as a group—must inevitably lag behind. The upshot: If we capture almost all of the market’s return by buying low-cost index funds, we’re guaranteed to outpace most other investors. That advantage, while modest in any given year, compounds over time, leaving us far ahead of most active investors.

What if we stray from an indexing strategy? There’s a chance we’ll beat the market, but there’s an even greater likelihood that we’ll fall behind, as our higher investment costs take their toll. That failure looks even more damaging once we factor in not only taxes—active management tends to generate big tax bills—but also time. Indexing is, in more ways than one, a no-brainer. By contrast, picking stocks and timing the market involves countless hours of effort, for which we’ll likely get punished rather than rewarded.

5. Knowledge is dangerous. To be fair, true knowledge isn’t dangerous. Instead, what’s dangerous is thinking we know something that’s unknowable—like which way stocks and bonds are headed next, or which individual stocks will outperform, or which fund managers will come out on top. This, of course, doesn’t prevent so-called experts from issuing an endless stream of predictions.

Don’t think you’re influenced by such forecasts? Next time you watch CNBC or Fox Business and there’s some astrologer—I mean, market strategist—pontificating about the stock market’s direction, ask whether you find yourself feeling a tad more bullish or bearish. Almost all of us are susceptible to a compelling market narrative. The big risk: It’s so compelling that we act on what we hear.

6. The difference between amateur investors and the pros is that the pros think more about risk. To be sure, for the pros, this is partly about career preservation: If they make a big investment bet and it backfires, they’ll likely be out of a job. But it’s also because it takes time and experience to become a veteran investor—one who fixates less on short-term performance and focuses more on risk.

I’ve seen no evidence that amateur investors, as a group, own a collection of stocks that’s any different from that owned by the pros. So why do a minority of amateur investors fare so poorly? In their lust for big short-term gains, they fail to consider risk.

7. Terrible results are the death of compounding. How do these amateur investors blow up their portfolios? Blame it on some combination of leverage and lack of diversification. That leverage might take the form of margin borrowing, selling naked put and call options, or perhaps owning leveraged exchange-traded funds.

If such bets go bad, they can be hugely difficult to recover from. Meet the brutal math of compounding: If you lose 50%, you need a 100% gain to get back to even. If you surrender 75%, you need a 300% gain to recover. What if you lose it all? Let’s hope you’re a good saver.

8. Just because it’s in the news doesn’t mean it should be in your portfolio. We can only sell investments that we already own (unless we short-sell, which is not advised) and we only buy investments that we hear about. And the investments we hear about most are those that are in the news. This year, that would include special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), ARK ETFs, bitcoin, nonfungible tokens (NFTs) and GameStop. Meanwhile, total market index funds don’t regularly make the news because they aren’t especially newsworthy—unless the focus is on earning impressive long-run returns without taking unnecessary risks.

9. The answer never changes. Every trading day, the Wall Street-Media Industrial Complex offers up a new horror movie. It might be higher taxes, or deflation, or tightening by the Federal Reserve, or recession, or the budget deficit, or inflation. What happens next? If today’s big fear comes to pass, stocks will tank—and then they’ll recover and go higher.

What does this mean for our portfolios? There’s no need to listen to the blathering of the talking heads, because the answer is always the same. We need a core position in stocks so we notch healthy long-run gains, while keeping enough in bonds and cash investments to make it through the rough periods, both financially and emotionally. That advice won’t get you three minutes on CNBC. But, yes, it really is that simple.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

Meet HumbleDollar's new sister site, BraggingBucks.com, designed for investors who can't quite shake that hankering for market-beating returns.

"As a parenting technique, some amount of intentional frugality can be useful," argues Adam Grossman. "Children won't always do as their parents say, but they will do as they see their parents do."

Read Juan Fourneau's story. He's a blue-collar worker at an Iowa chemical plant—and the owner of eight rental properties.

Want to protect your financial accounts and make it easier to keep track of your passwords? It's time to sign up for a password manager, reckons Phil Kernen.

"TurboTax and its ilk are the perfect black box," writes Michael Flack. "They give answers without understanding and facilitate forms without context. It has cost me more than a couple of bucks."

Befuddled by all the hoopla over SPACs, ARK and NFTs? William Ehart offers a guided tour to the recent market mania.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post Risk Less Make More appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 2, 2021

From SPACs to Space

WAS MARCH WHEN YOU learned what a nonfungible token was, because a digital file sold for $69 million? Was it when you told yourself you just had to find out more about SPACs? When you realized that the nation’s hottest fund manager, Cathie Wood, who you first heard about in February, was now a household name referred to simply as Cathie? As in, “Why does Cathie own Deere and Netflix in her new space exploration ETF?”

Then you and I are most definitely late to the party—and it’s probably best not to start dancing on the tables with the others.

With celebrities such as baseball great A-Rod and singer Ciara getting involved with SPACs, or special purpose acquisition companies, the Securities and Exchange Commission felt compelled to warn investors on March 10 against investing based on star power alone. Eccentric Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk, who reportedly briefly eclipsed Amazon’s Jeff Bezos as the world’s richest person, took his turn at the karaoke mic on March 15, offering to sell a tweet, which includes a link to a song about nonfungible tokens (NFTs), as an NFT.

Josh Brown of Ritholtz Asset Management described the “grotesque spectacle” best in his March 16 blog post, “Reverse Wealth Transfer on Steroids.” He advised younger investors, “Do not buy SPACs, digital currencies or nonfungible tokens sold to you by millionaires and billionaires with your stimulus check…. They don’t love you back.” He suggested more worthwhile pursuits, such as upgrading your apartment so you can bring a date home. The Wall Street Journal summed things up this way: “Meme Stocks, NFTs, Tech Rotation Dominate Crazy Quarter on Wall Street.”

HumbleDollar exists to provide timeless, simple advice to everyday investors. Yes, your best bet is to buy and hold a diversified portfolio, preferably one built using index funds. No, you don’t need to know much about today’s overhyped investment products, except that they may be a sign of irrational exuberance. Buying NFTs and celebrity SPACs? As they say in poker, “If you’ve been at the table for 30 minutes and you don’t know who the patsy is, you are.”

Hot and not. The S&P 500-stock index closed the first quarter near its record high, which was set March 26. But it was value stocks, especially in the small- and mid-cap segments, that led the way in this year’s first three months. The Vanguard Small-Cap Value ETF gained nearly 17%, versus the iShares Core S&P 500 ETF’s advance of just over 6%. The large-cap oriented Vanguard Value ETF rose more than 11%. Reflationary plays dominated as ETFs representing the energy, financials, leisure, industrials and materials sectors all posted double-digit gains, with real estate not far behind.

Meanwhile, gold and bond ETFs—especially those owning long-term Treasurys—fell sharply. Bloomberg reported that this year’s first three months was the worst quarter for Treasurys since 1980. The iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF fell 3.4%. The Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF dropped 13.4%.

Dollar demand. Helped by a spike in U.S. Treasury yields back to pre-pandemic levels, the dollar has gained 3.6% against a basket of six major currencies so far this year. That has held back returns on international funds. The iShares MSCI EAFE ETF, which tracks developed country performance, gained 4%, as did the Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF. But foreign value stocks still outperformed the S&P 500: The iShares MSCI EAFE Value ETF jumped 8%.

ARKs in space? Or falling to earth? Talk about a star fund manager. The aforementioned Cathie, whose actively managed ARK Innovation ETF has gained more than 46% per year over the past five years, debuted the ARK Space Exploration and Innovation Fund on March 30 to heavy trading volume. But her flagship fund fell 8% in March and nearly 4% in the first quarter, while concerns grew about its heavy ownership of illiquid stocks.

Aggravating those worries: Late last month, ARK Invest amended fund prospectuses to eliminate certain stock ownership limits in its ETFs. The amendment would allow each fund to invest as much as 30% of fund assets in a single company's securities and own as much as 20% of any single company or fund's shares. There was no way to predict ARK Innovation’s stellar performance five years ago, but what we can predict is that the fund family’s tremendous asset growth will make it awfully difficult to beat the market in the years to come. In investing, the word “gravity” is spelled “reversion to the mean.”

Sputtering SPACs. The boom in SPACs fueled the strongest quarter for global mergers and acquisitions since 1980, with deals worth $1.3 trillion, the Financial Times reported. Indeed, SPAC issuance in the first quarter of $97 billion has already topped the $83 billion recorded for all of last year. There were 298 SPAC initial public offerings (IPOs) in the first quarter, compared with 248 last year and just 59 in 2019. But it seems there’s a limit to everything: First-day SPAC IPO share price performance was uncharacteristically flat in March, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Sputtering SPACs. The boom in SPACs fueled the strongest quarter for global mergers and acquisitions since 1980, with deals worth $1.3 trillion, the Financial Times reported. Indeed, SPAC issuance in the first quarter of $97 billion has already topped the $83 billion recorded for all of last year. There were 298 SPAC initial public offerings (IPOs) in the first quarter, compared with 248 last year and just 59 in 2019. But it seems there’s a limit to everything: First-day SPAC IPO share price performance was uncharacteristically flat in March, The Wall Street Journal reported.

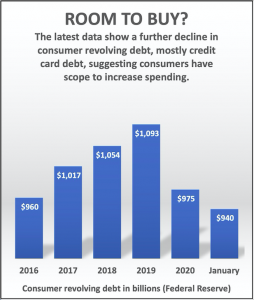

Credit where it’s due. In January, consumer revolving debt—which is mostly made up of credit card debt—fell to its lowest level since 2016, according to the latest Federal Reserve figures. With new federal stimulus payments of $1,400 still hitting Americans’ bank accounts, consumer spending could be poised for a huge increase. In fact, some are expecting an historic economic boom this year. On March 15, Goldman Sachs predicted 8% GDP growth in 2021, which would be the highest since 1951.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

The post From SPACs to Space appeared first on HumbleDollar.