Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 15

September 23, 2025

Thank you, Jonathan

I hope I’m not overstepping here, but since I read the news yesterday, I’ve been thinking that it would be nice to have a thread in which we thank Jonathan for the various ways he touched our lives, whether it be as a writer or just a manager of our finances. I’m hoping it’s something his family might enjoy reading when they’re ready.

So here’s mine:

Unlike many of you who go back to Jonathan’s WSJ days, I only discovered him and HumbleDollar in 2020, early in the pandemic. I don’t recall exactly how I came across it, but I definitely remember reading Dick Quinn’s articles about being stuck on the cruise ship after COVID hit. I think those were the first ones, and then I started poking around through the other articles, and subscribed to the twice-weekly newsletter.

Over the next couple of years, I began to think about proposing an article myself to Jonathan and even started keeping a list of ideas. Finally, in early 2023, I got up my nerve and wrote to him. He couldn’t have been more welcoming, encouraging, and helpful. Between 2023 and when HD stopped publishing articles, I published 9 pieces edited by Jonathan. I was so impressed that he shared the platform he’d created with such a wide variety of people. I’m no financial expert—honestly, I barely understand investing—but like so many other HD authors, I had life experience and stories to share.

So thank you, Jonathan, for giving me a seat at this table and helping me find my voice.

What about you? Please share here if you feel moved to do so.

Thank you, Jonathan.—Dana Ferris

The post Thank you, Jonathan appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Nick Maggiulli’s take on Bergen’s 4.7 or 5% Withdrawal Rate

https://ofdollarsanddata.com/why-the-...

An additional take on Bergen's new book and data, which I posted about 6-8 weeks ago.

Nothing for me to add except Nick is a smart guy, and the table in the article is pretty compelling.

The post Nick Maggiulli’s take on Bergen’s 4.7 or 5% Withdrawal Rate appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Success Has Many Flavours

Being in Spain at the moment, I took the opportunity to use the excellent train network to travel and see my father-in-law, who has lived in the country full-time since retiring ten years ago.

He lives comfortably, if humbly, within his means. A UK state pension and a small personal retirement account to bolster it are all he requires. I don't think I could live on his retirement income, and I don't think he could have managed without the geoarbitrage he undertook to make it work.

A messy late-life divorce a few years before retiring, and significant personal debt in the aftermath, left him in a very precarious position at such a crucial time in his life. It was a bleak outlook indeed, as he confided to me at the time.

His saving grace was being able to hold onto his Spanish property and completely transform his outlook toward money and debt. By being diligent and making tough choices, he managed to climb out of the swamp of debt during his final five years of working life.

I always think of my father-in-law's journey as a shining example of the human ability to overcome major hurdles. His ability to find a pathway to a modest but content and fulfilling retirement is humbling.

Sometimes I feel that on Humble Dollar, the subtle underlying narrative contrasts this more basic type of retirement with a taint of failure. Maybe for some, by their personal yardstick, it would be. To me, that's not the case.

Personal contentment and happiness, combined with peace of mind and a social circle of friends, are in my opinion more often than not a better measure of someone's retirement situation than the size and performance of their portfolio.

To target a humble, modest retirement—by choice or by necessity—is just as valid as striving for one of plenty, and it's something we should be mindful of. The old adage that money isn't everything certainly rings true with my father-in-law. Success has many flavours.

The post Success Has Many Flavours appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 22, 2025

Farewell Friends

I'm hoping that, under the tree in front of our little Philadelphia rowhome, my wife Elaine will place a stone tablet inscribed with my name, and the year I was born and died. Underneath, I'd like the tablet to read:

Family • Readers • Words

(Note to Elaine: If you ever move, feel free to take the tablet with you.)

Family is everybody who's brought love into my life: Elaine, my two children, my larger family, my close friends. Meanwhile, readers have been those I've served, and who rewarded that service with so much loyalty and affection. Finally, words have been my playground, taking the insights I've garnered and trying to make them understandable to others. Beside the tree are two metal chairs. I hope family and passersby will occasionally stop by, and fill me in on what I've been missing.

I've asked Elaine to arrange a memorial service at St Peter's Church in Philadelphia's Old City. She'll post the time and date to the Forum when the details have been worked out.

Regular readers will know much of my life's story. But I figure it's appropriate to offer a not-so-brief recap.

I was born at 14 St Margarets Drive in Twickenham, London, on Jan. 2, 1963. At that time in the UK, it was standard practice for mothers to give birth in the hospital if it was their first child—or, in my mother's case, her first two children. My older brothers, who are identical twins, had been born two years earlier. Because that first delivery went smoothly, my birth would be at home. From what I gather, the midwife took cigarette and scotch breaks with my father during lulls in the action. I was born at 6 a.m., thus establishing a lifetime habit of starting early.

In 1966, my father left financial journalism for a job at the World Bank, and we moved from London to Washington, DC. Two years later, my younger sister was born. In late 1972, my father was posted to the World Bank's Bangladesh office for four years, and I was dispatched to boarding school in England, joining my two brothers.

After the comforts of a U.S. suburban childhood, it was a brutal change—cold dormitories, disgusting food, endless bullying—and I carried the scars for the rest of my life. But there was a silver lining: After nine years of boarding school, I squeaked into Cambridge University, where I spent much of my three years writing for and editing the student newspaper.

When I graduated Cambridge in 1985, the UK economy was in rough shape and landing a job was difficult. I ended up working for Euromoney magazine in London. Initially, all went well. But then there was a change in editor and, for reasons I never understood, the new editor took an instant dislike to me and made it clear he wanted me gone. But by then, I'd already decided to leave London and return to the U.S.

My then-fiancee and I flew to New York in August 1986. After a desperate scramble, I landed a job as a reporter—read "fact checker"—at Forbes magazine. The pay was miserable, but I couldn't have been more grateful for that first paycheck. By then, all I had to my name was credit card debt.

Molly and I were married the following June, and Hannah arrived 15 months later. Her younger brother, Henry, would follow in 1992.

After 23 months as a fact checker, I was promoted to staff writer at Forbes, covering mutual funds. The Wall Street Journal, which was also in need of a funds reporter, came calling 16 months later. I'd always thought I'd never be a real journalist until I worked for a daily newspaper, and yet initially I said no.

At the time, I was in the midst of six months as a single parent, looking after Hannah on my own while Molly was in Syria, Greece and Turkey conducting research for her PhD. Still, the Journal wasn't deterred, saying it would make allowances during my initial months.

In the early 1990s, the Journal was very different from the newspaper it is today. No photos, just the dot drawings for which the paper was renowned. While strong opinions could be found on the editorial page, they were to be avoided in the news pages. The sort of advice journalism I favored was frowned upon by some among the paper's senior ranks.

Still, in 1994, Managing Editor Paul Steiger said he'd consider a few columnists for the Journal's news pages. At age 31, and with some trepidation, I put up my hand. Thus was born the Getting Going column, which I wrote for the next 13-plus years, penning 1,009 columns for both The Wall Street Journal and Wall Street Journal Sunday. The latter were branded pages that appeared in some 70 newspapers around the country.

In retrospect, it's astonishing that I was given my own column at such a young age. It took me a few months to hit my stride, but I was soon pounding away at the virtues of index funds, while also exploring new topics, often scouring academic research for insights I could share with readers.

The decade and a half that followed are something of a blur. I was cranking out columns, commuting into New York City from the New Jersey suburbs, and raising two children. In my memory, the years have the monotony of a hamster wheel. But that wasn't the reality: There were high points and low points, plus the joy of watching Hannah and Henry grow up. The low points included the World Trade Center attack, my father's death and a libel suit brought against the Journal. I'd been involved in editing the story that triggered the lawsuit.

In early 1995, while in Pittsburgh, I went on a nine-mile run with my brother-in-law, who was training for the city's marathon. I'd long viewed running those 26.2 miles as a heroic endeavor. I committed to returning for the next year's marathon. But I didn't simply want to complete the distance. Instead, I set a goal of finishing in under three hours. I managed it, though barely, crossing the finish line 24 seconds under the three-hour mark.

I ran countless road races over the next dozen years. I had my greatest success with half-marathons, finishing third in the four races I ran on land—and first in the 2001 half-marathon held on the deck of a boat floating off Antarctica. In shorter races, from one mile to 10, I also managed perhaps a dozen first-place finishes. What about the tearful, wimpy English schoolboy who had previously shunned athletic endeavors? Over countless miles, I managed to leave him behind.

Career and athletic success were not, alas, rivaled by relationship success. Molly announced she wanted a divorce in 1998. It would be the first of two failed marriages—not an achievement I'm proud of. But the third time was a charm. In the midst of the pandemic, Elaine and I met in August 2020, the month my second marriage officially ended. We were living together by the end of the month and married almost four years later, in May 2024, five days after my cancer diagnosis. I met Elaine during one of my life's roughest periods, and was so lucky to have done so. Elaine, I fear, was not so fortunate, for now she must navigate the world on her own.

By 2006 or so, I'd started to tire of the Getting Going column, and began casting around for what to do next. I had a few conversations with potential employers, but those came to naught. Then, one day in early 2008, my phone rang. It was Andy Seig from Citigroup. He was heading up a startup within Citi known as myFi, which was aiming to deliver advice on a client's entire financial life in return for a flat monthly fee. It was, I imagined, the exit from the Journal I was looking for.

I joined myFi that spring, and it soon became apparent that launching a startup in the middle of a huge corporate bureaucracy was a foolhardy endeavor. Layered on top of that was the financial crisis that unfolded through the year. By mid-2009, myFi was dead, and we employees spent a long, aimless summer trying to figure out what was next.

Next turned out to be a new wealth management operation cobbled together by combining myFi's remaining employees, who had been hired to launch an innovative new financial service, and the old school brokers who sat in Citi's bank branches. It wasn't exactly a match made in heaven.

I toughed it out at Citi until spring 2014. Money was undoubtedly part of the reason. I was making more than $300,000 a year, a gaudy sum for a onetime ink-stained wretch. And the job wasn't without interest. As director of financial education for the U.S. wealth management business, I gave more than 30 speeches in some years—forcing me to overcome my fear of public speaking—and I was dealing with financial topics I'd rarely written about as a journalist, while also learning about the investment business from the inside. Still, I was also frustrated by the nit-picky oversight of lawyers and compliance officers, and vowed to leave.

For a year, I planned my departure, getting my finances in order and setting in motion some work projects for my life after Citi. I waited until I got my final year-end bonus in early 2014, and then handed in my notice.

What followed was a period I came to call my second childhood. Initially, that meant a 15-month return to The Wall Street Journal as a freelance columnist—I left when my editor got ousted during a round of layoffs in 2015—and also working on two annual editions of the Jonathan Clements Money Guide. That guide eventually became the core of HumbleDollar, which I launched on Dec. 31, 2016.

The two printed editions of the money guide were among the nine books I wrote over my career—eight personal finance books and a novel. I also edited two books, including My Money Journey , a compilation of 30 essays by HumbleDollar writers, and contributed essays to a fistful of other tomes, including penning the foreword to two Bill Bernstein books. None of the books I authored was a huge success. But my favorite, and the one with the best sales, was my 2016 book, How to Think About Money .

In 2016, I was also contacted by Peter Mallouk, president of fast-growing Creative Planning, a registered investment advisor that favored index funds and sought to help clients with their entire financial life. As at Citi, I was again given the title of director of financial education, though I remained an independent contractor and worked limited hours for Creative. Still, for me, it proved to be one of my career's most enjoyable professional relationships. Peter was great to work with, and together we hosted a monthly podcast that ran for the rest of my life.

By May 2024, I'd been living in Philadelphia for more than three years, I was engaged to Elaine and living just an eight-minute walk from my daughter, son-in-law and two grandsons. The youngest was born that month. Elaine and I were talking about retirement, trying to figure out how we could travel more and have more time for each other, even as I kept HumbleDollar humming along.

And then I got my cancer diagnosis.

The period immediately after was astonishingly busy, as I tried to get my affairs in order and prep HumbleDollar for a life without me, even as my diagnosis triggered a surprising amount of media attention. The New York Times wrote about my illness, I was interviewed for Consuelo Mack's WealthTrack , and I was asked to pen articles for The Washington Post , The Telegraph of London, The Wall Street Journal and AARP magazine. Who knew that candor about one's own death would generate so much interest? It was an odd bookend to a life spent partly in the public eye—one that had previously been most notable for pounding the table for index funds.

I faced the final months not with sorrow, but with great gratitude. I had spent almost my entire adult life doing what I love and surrounded by those that I love. Who could ask for more?

The post Farewell Friends appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Unhealthy Inflation Expectations?

Its use isn't limited to envisioning potential growth of investments. It can also help imagine the outcome on our lives from a shrinking process which melts the purchasing power of money like an ice cube on a summer day: inflation.

According to the 2025 Global Investment Returns Yearbook, by Dimson, Marsh, and Stanton (published now by UBS), the U.S.'s average annual rate of inflation over the past 125 years has been 2.9% (geometric mean), or 3.0% based on an arithmetic mean. Using that latter round number, the rule of 72 suggests our purchasing power could be cut in half in 24 years (72 divided by 3) if our income doesn't keep up with inflation.

The CPI inflation indexes were created using a basket of items which may or may not reflect how each of us spends our money. But there is one item which all of us need: healthcare. Adam Grossman posted a piece in 2021 ("Their Loss, Your Gain") about LTC insurance; in that, he linked to a FRED blog post which showed how healthcare costs since 1948 grew at an average rate about 1.5 percentage points higher than the general CPI rate. Envisioning that trend with the Rule of 72, we would spend twice as much on healthcare costs every 16 years (72 divided by 3.0 + 1.5).

I would expect health insurance premium inflation to track healthcare cost inflation, but I'm no expert on this topic. A recent post by Dick Quinn drew my attention to pages 204 and 205 in the most recent report by the Board of Trustees for Medicare. On those pages, you'll find two interesting tables, one which estimates the future monthly premiums for Medicare Part B and Part D through 2034, and another which estimates the future income-related monthly adjustment amount (IRMAA) to the base Medicare Part B premium. When I dropped those figures into my financial planning spreadsheet, I was surprised to see the Trustees expect Part B premium increases averaging roughly 7.2%. The IRMAA increases tracked at roughly the same rate.

I'm not sure how to think about these "intermediate estimates" in this Trustees report. Is it really possible we'll see the purchasing power of our Medicare dollars cut in half every 10 years (72 divided by 7.2)? Yikes.

The post Unhealthy Inflation Expectations? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Inflation is many different things to different people

It’s easy to learn the inflation rate, it’s published monthly, generally the CPI- W applicable to retirees. But what really counts is your individual rate because you may or may not be affected by the components of the index.

Years ago I signed up for and received my individual monthly inflation rate - based on a questionnaire- from the Federal Reserve. Then the message just stopped coming.

In any case, it might be interesting to build your own inflation rate based on what items mostly apply to you

For example, we don’t rent, but we pay property taxes whose increase rate are capped in our state. Our health care expenses are pretty much limited to premium increases, but that may not be the case if there is a high deductible.

Feel free to use a spreadsheet for the exercise 😁🤑😁

The post Inflation is many different things to different people appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 21, 2025

Achieving and maintaining all the retirement income you need for a chosen lifestyle with limited worry.

I read now on HD concern for the 4% withdrawal strategy, potential - inevitable - market declines, the lack of COLAs in pensions (mine included) and annuities, asset allocation, general concern about preserving life-long retirement income and more. All of which is clearly justified.

I have said many times and been criticized as often, that the key to a secure retirement is a strategy that provides more steady income than one thinks they need based on pre-retirement income and lifestyle. It’s a cushion, insurance if you will.

Regardless of what a calculator may show, starting retirement with 70-80% or even I’ve read 40% of pre- retirement income is risky business or at least if events turn sour, cause for sleepless nights. I also suggest that the more modest a persons income, the greater the risk. No matter how frugally or modestly people live, stuff happens before and after retirement.

Knowing I had a pension and Social Security and following the belief we were not going to spend less in retirement-that’s aggregate spending beyond necessities including some ongoing modest saving, helping family, travel, giving, etc., I built assets that would generate income when needed and deal with emergencies. The assets come from a 401k plan and non-qualified investments over my working life. However, I also did not spend bonuses and retained stock compensation that only started when I was age 62.

My strategy was and is simple, don’t plan for change in lifestyle, plan to continue your lifestyle and plan for as much of the “what if” as possible. In other words, live as far away from the edge, the adequate, the sufficient as possible. And, it’s all relative to doing so based on a persons pre-retirement income.

My retirement planning was solely focused on replacing my pre-retirement salary, nothing else was considered. Yes, a pension made the goal easier, but I cannot see myself doing anything different even with investments and a purchased annuity although no doubt our pre-retirement lifestyle would have been different. I also admit it would have been a struggle if my goals included early retirement.

There are different approaches for sure, but isn’t the common goal all the income you need for as long as you need it regardless of uncontrollable events?

The post Achieving and maintaining all the retirement income you need for a chosen lifestyle with limited worry. appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 20, 2025

The Gnashing of Teeth

I'm going to curse myself, question my own intelligence, spend nights sleeping poorly, and firmly consider the wisdom of "stay the course" as no more useful than a chocolate fireguard. Checking my portfolio balance will become a preoccupation to make myself nauseous.

The market is at an all-time high, every metric is stretched, and knowing how I'm going to react come the inevitable correction, I'm still not changing my asset allocation. But I have made preparations—I've purchased sick bags.

My reaction to the "big drop" is going to be mirrored by many throughout the world. The gnashing of teeth will become audible, a constant background noise to our emotional pain, but strangely enough, this massive correction will only affect us "sophisticated" investors.

The vast majority will maybe see something on the news, probably just before switching over to the big sporting event. Our front-and-center pain will pass them by. Lack of financial interest will be their savior.

Unknowingly they will practice the art of "tuning out the noise."I wonder, who really is the "sophisticated" investor? Those of us who protest the inevitable, or those who ignore the volatility—maybe by indifference, but definitely by choosing to get on with life?

Is the checkout clerk who never looks at their 401k balance practicing a more advanced form of investing than those of us obsessively tracking every market move during a downturn? Maybe we should endeavour to embrace some form of “ignorance is bliss”.

The post The Gnashing of Teeth appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 19, 2025

Best Bond Funds for Your Portfolio: Treasurys, Corporates, and Municipals Explained

The bond market is actually much larger and much more diverse than the stock market. For most investors, though, there are just a few types of bonds to consider. We can examine each in turn:

Total Bond Market

Perhaps the most well known type of bond investment is a total-market fund. All major fund providers, including Vanguard (ticker: BND) and iShares (ticker: AGG), offer funds tracking the total-bond market index.

The key advantage of funds like this is that they’re broadly diversified, holding a mix of U.S. Treasury bonds, for stability, and corporate bonds, for their higher yields. That’s why many people see this as the easiest and best way to invest in bonds.

The downside of total-market funds, though, stems from a metric known as duration. A bond’s duration is similar to its maturity and is an indicator of its riskiness. The intuition is that bonds are like IOUs. To the extent that an IOU will be paid back sooner rather than later, it inherently carries less risk. Similarly, bonds that require an investor to wait longer for repayment carry more risk.

More specifically, when interest rates rise, bonds can drop in value. That’s because older bonds, which were issued at lower rates, become relatively less attractive than newer bonds carrying higher rates. When this occurs, bonds with longer durations experience larger declines.

The problem with total-market funds is that their average duration is relatively long, and this makes them risky. We saw this most notably in 2022, when the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates in an effort to tamp down inflation. Total-market funds lost about 13%. While that type of loss wouldn't be unheard of in the stock market, this is not what investors expect from bonds.

For that reason, while you might have some allocation to a fund like this, I generally avoid them.

What alternatives are there to total-market funds?

Corporate Bonds

You could opt for a fund that holds high-quality corporate bonds. These are bonds issued by large, solid companies like Microsoft and Bank of America.

These carry two potential advantages over total-market funds:

First, there’s the potential to earn more, since, on average, companies have to offer higher coupon rates than the government in order to entice buyers.

Also, when you move away from total-market funds, you can break free from the duration risk described above. Funds like Vanguard’s short-term corporate bond ETF (ticker: VCSH), for example, carry much shorter durations. That’s why funds like this fared much better in 2022, losing less than 6%.

Despite these advantages, corporate bonds aren’t ideal, because they carry another type of risk:

They tend to be positively correlated with the stock market, meaning that they often move in unison. That’s the opposite of what an investor would want.

We saw this dynamic most recently in the spring of 2020. In the early days of Covid, when the S&P 500 dropped more than 30%, corporate bonds sank as well. Even short-term corporate bonds lost more than 10%. In contrast, short-term Treasury bonds gained in value.

That brings us to the next category of bonds you might consider:

Treasury Bonds

U.S. Treasury bonds have historically been the most secure. With arguably only one exception, the U.S. government has never missed a bond payment. That’s why finance textbooks will refer to Treasurys as the “riskless asset.” And that’s why Treasurys would always be my first choice. But we should be careful about seeing them as truly riskless. There are two situations in which even Treasury bonds can pose risk.

First, Treasurys carry duration risk, just like any other bond. In 2022, intermediate-term Treasurys lost more than 10%, and long-term Treasurys lost nearly 30%. The solution? You might weight your holdings toward short-term issues. In 2022, short-term Treasurys lost an almost insignificant 4% of their value.

The second risk with Treasurys is harder to quantify, and that’s the risk posed by Congress.

More than once in recent years, the political parties have come to a stalemate in budgetary debates, and that’s taken us uncomfortably close to the so-called debt ceiling, beyond which the government might not have been able to pay its bills, including payments to bondholders.

How real is this risk? It’s hard to say, and personally, this is not a risk I worry a lot about.

The reality, though, is that there’s a first time for everything. That’s why you might consider diversifying beyond Treasurys into what I see as the next best thing:

State and Local Government Bonds (Municipals)

Municipal bonds are similar to Treasurys in that many cities and states have the authority to levy taxes, helping ensure that they’ll always have the funds available to make payments to bondholders. That makes municipals, in general, relatively low-risk. But two significant caveats apply:

First, the municipal market is very diverse, and while some bonds are backed by tax-collecting entities, others are not. And sometimes even seemingly safe municipal entities can face financial stress.

In 2020, at the outset of Covid, the New York City subway system saw ridership fall 92%. If the Federal Reserve Bank of New York hadn’t provided billions in emergency funding, the transit authority would have defaulted on its bonds.

Another way in which municipal bonds carry more risk than Treasurys: In colloquial terms, the federal government can print money. It’s more complicated than that, but the idea is that it would be very difficult for the Treasury to truly run out of money, and that’s why no municipal bond can ever be considered as secure as a Treasury bond. Taking a step back, though, highly-rated municipals rarely default, and especially if you stick with short-term issues, the risk is very low.

Municipal bonds carry another unique characteristic:

They are exempt from federal tax. And if you live in the state where a bond was issued, it’ll be free of state tax as well. In exchange for this benefit, though, the coupon payments on municipal bonds are generally lower than on comparable Treasurys. For those in marginal tax brackets over 30%, though, the tax savings can offset those lower coupon rates.

There are many other categories of bonds. For most investors, though, it doesn’t need to be more complicated.

To build a balanced portfolio, you might consider a simple mix of four Vanguard funds:

Short-Term Treasury (ticker: VGSH),

Short-Term Tax-Exempt (ticker: VTES),

Intermediate-Term Treasury (ticker: VGIT), and

Short-Term Inflation-Protected Securities (ticker: VTIP).

There was also a good discussion by a Forum member titled "Is now the time to go long in bonds?" that you might find interesting.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Best Bond Funds for Your Portfolio: Treasurys, Corporates, and Municipals Explained appeared first on HumbleDollar.

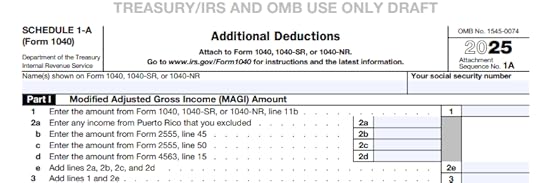

New 2025 Tax Deductions

I wanted to quickly go through some of it, so that you are more aware of the new potential savings opportunities.

I’ve previously discussed some portions of the bill, but this is the first time we have a peek of the new lines.

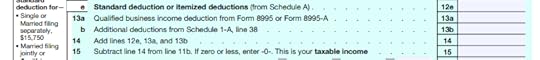

All of these deductions are in addition to the standard deduction or itemized deduction.

All of them are tied to Schedule 1-A, line 3, which pulls your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) from Form 1040, line 11:

This AGI number is critical. If you’re over certain limits, the deductions below will phase out or "disappear".

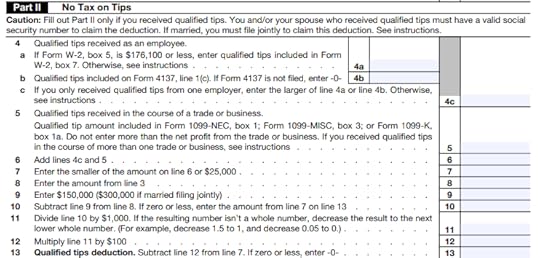

“No tax on tips”

The first deduction on Schedule 1-A is the “no tax on tips”.

If you haven’t received any tips in your job, this of course wouldn’t apply to you. If you receive qualified tips, that amount should be included on Form W-2, box 7, if you are an employee.

You can also deduct qualified tips earned as a self employed person, so make sure to track them (Line 5). This is of course if these tips are qualified, and is from an occupation that “customary and regularly received tips before December 31, 2024”. Here’s a published list from the Treasury of which occupations qualify.

If you earn more than $150,000 single or $300,000 married (from line 3), the maximum allowable tip deduction will be reduced by $100 for each $1,000 over (line 9-12). For example, a single filer with $155,000 AGI would see the maximum tip deduction ($25,000) reduced by $500.

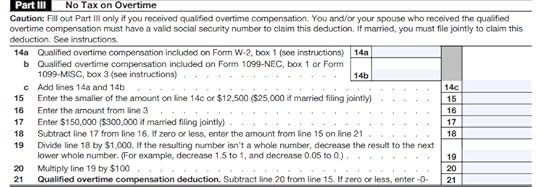

“No tax on overtime”

To get the “qualified overtime compensation deduction” your overtime must be "qualified". The IRS hasn’t posted any instructions yet on Schedule 1-A, but based on the tax bill we know that the deduction applies to non-exempt employees who receive overtime pay under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). So if you are an exempt employee, this wouldn’t apply to you.

The 2025 tax year is an initial rollout, and more guidance is expected from the IRS soon. 2026 and forward, the IRS will require payroll companies to provide W-2 forms that include that amount.

Similarly to the tips deduction, everything will depend on your income level (Line 3) and the deduction will be phased out if you are over the limit.

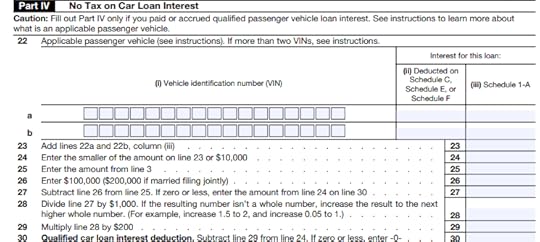

“No Tax on Car Loan Interest”

If you have an applicable passenger vehicle (acquired in 2025 or after, must have been new, and assembled in the US), you can deduct qualified interest. You would have to provide the VIN for the car(s). The lender will be required to provide that information via an informational form (like Form 1098).

If you are over the $100,000 or $200,000 (married jointly), the maximum $10,000 loan interest deduction is phased out. See my recent post for more details.

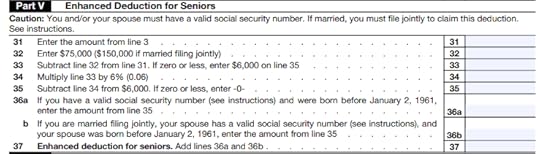

“Enhanced Deduction for Seniors”

If you are 65 or over, you can receive a $6,000 deduction if Line 3 is below $75,000 single or $150,000 married filing jointly. If it’s over the threshold, it will be reduced by 6%. If your spouse is also 65 or older, they will receive the same amount.

For example, a single 70-year-old with $80,000 AGI on Line 3 would see their deduction reduced by $300 (6% of $5,000).

All of these deductions are summarized and entered on Line 13b of your Form 1040:

The deduction will reduce your taxable income, which lowers your federal income tax bill.

It is still uncertain which states will conform to the federal changes. For example, the governor of Colorado is trying to analyze the impact of $1.2B revenue loss due to conformity to the federal rules.

I would expect more lobbying happening over the next few months to determine which provisions the states would conform to, likely many business provisions (e.g. 100% bonus depreciation) will be enacted.

If not, even though certain items will be deductible on the federal level (like car loan interest), it might be added back to the income for state purposes. More details to come.

Bogdan Sheremeta is a licensed CPA based in Illinois with experience at Deloitte and a Fortune 200 multinational. He shares insights on taxes and personal finance through his newsletter, helping thousands of readers to make smarter financial decisions. He has over 140,000 followers on X and 110,000 on Instagram.

Bogdan Sheremeta is a licensed CPA based in Illinois with experience at Deloitte and a Fortune 200 multinational. He shares insights on taxes and personal finance through his newsletter, helping thousands of readers to make smarter financial decisions. He has over 140,000 followers on X and 110,000 on Instagram.The post New 2025 Tax Deductions appeared first on HumbleDollar.