Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 123

September 18, 2023

Rise of the Ronin

SAMURAI WERE EMPLOYED by feudal lords in Japan. They were skilled in the art of combat and highly trained—the best of the best.

A ronin—meaning a "drifter" or "wanderer"—was a samurai who’d left his clan, usually when his master died. Upon leaving, he was free to use his skills to seek similar employment elsewhere or even to choose a completely different profession. A ronin then relied entirely on himself and his skills to get by. Most ronin were self-reliant, self-disciplined and very good at whatever they chose to do.

My friend Simon is a modern-day ronin.

Simon used to be like the rest of us, living by the rules and doing what was expected of him: graduating from university, securing a well-paying corporate job, getting married, buying a home, starting a family. He was careful with money—something his parents taught him—living within his means, paying down debt and saving as much as possible, so he could retire comfortably one day.

Things changed for Simon when his older sister became ill and he almost lost her. That experience served to remind Simon about what’s important in his life—his family—and what isn’t, which was spending most of his time working. He realized he was caught in a trap, trading his quality of life for money, and he didn’t want to play that game anymore.

He ran the numbers and calculated that he’d saved up enough money so he could work less and enjoy life on his own terms. He knew that he’d need to keep working to some degree to fund the lifestyle he was accustomed to, but now he could do work he enjoyed without worrying about how to pay the bills.

Because of the retirement assets he’s accumulated and the passive income it generates, Simon doesn’t have to make a lot of money. He just needs enough to cover his entertainment expenses and maybe put a little in savings. Simon can make $40,000 a year and yet have a happier life, one with less stress than his former self suffered while working for a bank making $200,000 a year.

How sweet is that?

Spending more quality time with friends and family, and doing work he loved, became Simon’s big “why.” His “why” gave him the confidence and courage to leave his well-paid corporate job to become a ronin and fend for himself.

His wife was supportive. But when he told his parents and coworkers what he intended to do, they thought he’d lost his mind and was going through a midlife crisis. They said he was crazy to give up what he’d worked so hard for, and it wasn’t going to turn out well for him and his family. But Simon was undeterred by the criticism and used his “why” to push forward with his plan. Today, these same people are in awe of what Simon has accomplished and some are a little envious of how happy he is.

Simon gets to call his own shots. He’s free to pursue work that’s interesting and meaningful to him. He works at multiple jobs at the same time, providing him with financial security and stability. When one source of income dries up or he decides he doesn’t like working there, he just moves on to something better. Having more than one source of income allows Simon to be picky when looking for something new to do, and it gives him more control over how and when he works.

These days, Simon would never do work that he doesn’t like, no matter how much it pays. He chooses how long he’s going to work at a particular place. He chooses when to take time off. He chooses the people he works with and the location he works at. No more brutal commute for him. He won’t tolerate a bad boss or a toxic work environment. While at work, his focus is on the job and learning as much as possible.

The pandemic was a massive trigger event for many workers. Forced isolation gave them a lot of time to think about themselves and the work they do. They realized how precious and short life is, and that it was a mistake to wait till they were retired to do all the fun things they’d planned. They know anything can happen and, if they wait, they could end up being physically unable to do the things they love to do. What if they got sick or their spouse died?

Because of the pandemic, many people decided they no longer wanted to waste their precious life working a stressful job, putting in their time while waiting to retire one day, so they could then be happy. This change in thinking led to the Great Resignation we recently witnessed.

But it’s far from over. I believe after a period of rest and reflection, together with a dose of reality, many of these folks will re-enter the workforce as ronin. These people want to continue to learn and contribute. They want to work for an organization led by someone they admire and for a cause they believe in.

Ronin like Simon don’t want to retire, although they could. They want to keep working, doing what they’re passionate about at their own pace and in jobs where they can call the shots. Quality of life substantially improves for people like Simon, when they’re able to cover their financial needs with both passive income and a paycheck from work they love to do.

Becoming a ronin changed Simon’s life for the better. If he could do it, there’s no reason you couldn’t do it as well. For the record, I’m teaching my kids to become ronin.

If you’d like to learn more about Simon’s story, download the free book I co-authored, Longevity Lifestyle by Design.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He’s the co-author of Longevity Lifestyle by Design,

Retirement Heaven or Hell

and

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to

BoomingEncore.com

. Check out his earlier articles.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He’s the co-author of Longevity Lifestyle by Design,

Retirement Heaven or Hell

and

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to

BoomingEncore.com

. Check out his earlier articles.The post Rise of the Ronin appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 17, 2023

Stick to the Classics

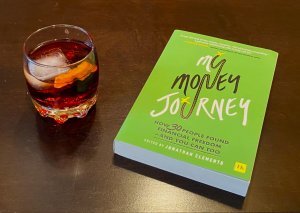

THERE’S ONLY ONE THING I like more than writing about personal finance, and that’s drinking a salubrious cocktail. When I realized I could combine both, this article almost wrote itself.

Two decades ago, I read the best cocktail book ever written, The Essential Cocktail: The Art of Mixing Perfect Drinks by Dale DeGroff. He thought so highly of my bartending skills that he even inscribed my copy, though that’s a whole other article. One drink stood out, the Negroni, an aperitif, that may be the greatest cocktail ever built over ice. For those teetotalers who don’t know what I’m talking about, it consists of Campari, sweet vermouth and gin, garnished with an orange peel.

The bitterness of the Campari—tempered by the sweet vermouth and with the gin’s kick—stokes the appetite and sharpens the senses, making it the perfect before dinner drink. When I first made it for my wife in early December sometime in the mid-2000s, she referred to it as the “Christmas drink,” due to its Christmassy red hue.

For the next two weeks, every day when I came home from work, she’d demand “make me the Christmas drink” until a few days before Dec. 25, when she declared, “I’m done, it’s played.” Hey, “to every thing there is a season.” Sometimes, the season ends, though we still enjoy one every now and then.

The Negroni, according to DeGroff, “was created in the bar at the Hotel Baglioni in 1925 when Count Camillo Negroni decided the Americano was too tame a drink. He asked for the barman to spike his Americano with a splash of gin” and—voilà—the Negroni was born.

Since 1925, people have been drinking the Negroni. While the 1:1:1 ratio may have been adjusted at the margins—you may want to try a skosh more Campari—the drink stands as a testament to evolution and simplicity. It’s much like grandma’s lasagna, Ted Williams’s eyesight and New York City pizza. Why mess with greatness?

Well, people do. Over the past few years, I’ve noticed a number of bartenders have tried to “improve” on this epitome of perfection.

A year ago, I ordered a Negroni at one of Kansas City’s finer drinking establishments and was rewarded with a drink that just didn’t taste right. When I inquired, the server explained to me that “we don’t use Campari in our restaurant.” To that, I elucidated, “Then, what you served me wasn’t a Negroni.”

When I subsequently explained this tale of woe to a bartender at Kansas City’s second finest drinking establishment, she heartily agreed. But she then served me a Negroni that didn’t have the required Christmassy hue. I was subsequently informed that it was made with blonde vermouth. “What is blonde vermouth?” you may ask. My response: As it’s not sweet vermouth, “Who cares?”

Just last month at the Belmond Hotel in Iguaçu Falls, Brazil, perhaps the best hotel in South America, I was offered a Negroni that—in addition to the essentials—contained Grand Marnier, Drambuie and grapefruit syrup. The server was nice enough to offer me a sample and, well, “No, Obrigado.” Unfortunately, I fear this won’t be the last time someone tries to improve on perfection.

Quite simply, the Negroni has evolved over the past 98 years to be the little bit of heaven that it is. I get that man is always trying to invent a better mousetrap, but can’t we focus our efforts on more important issues, such as merely expensive first class airline travel, mediocre New York Jets football and middle shelf bourbon?

What does this have to do with finance? Over the past 98 years, rational (and humble) investors have come to realize that, much like the Negroni, there are three basic securities: stocks, bonds and cash. And much like the Negroni, some financial bartenders try to “improve” on these classics.

Recently, a financial advisor offered me the opportunity to buy a fund that invested in Texas real estate property tax loans. The fund boasted a steady return that was a little behind the S&P 500, but with less risk. It all seemed very delectable, until I realized it was really just a bond fund, with an expense ratio north of 1%, which was in addition to the advisor’s 1% take. And then it all seemed, well, just a little less appetizing.

Before that, I was almost tempted to invest in securitized fine art via Masterworks. It seemed quite enticing until I realized that the fee structure was a little too opaque. I detailed its excessive bitterness in a prior article.

I mean, what’s next, investing in nickels for their melt value? Never mind. Someone has already attempted to arbitrage that “gold mine.”

When it comes to my finances, much like my cocktails, I prefer to stick with the classics, like a well-built Negroni, a Marlowian Gimlet or a Manhattan on the rocks. I think it’s better for my appetite, constitution and wallet.

The next time you’re in your favorite drinking establishment, after—of course—verifying the ingredients, order a Negroni. When you drink it, think about the simplicity of your spirits and your finances. An even better idea: Make one yourself.

The Humble Negroni

The Humble Negroni

1¼ oz. Campari

1 oz. sweet vermouth

1 oz. gin

Orange slice, for garnish

Directions: Combine the gin, sweet vermouth and Campari in an ice-filled old-fashioned glass. Thoroughly stir. Garnish with the orange slice.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.The post Stick to the Classics appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Shrink That Estate

I OUTLINED 10 REASONS everybody should have an estate plan in a 2018 article—and what was true then remains true today, especially for those whose assets could be subject to estate taxes.

Under today’s rules, the federal estate tax applies to individuals with assets over $12.9 million. That might sound like a high number. But in 2026, the limit is set to be cut in half. In addition, many states impose their own estate tax, which kicks in at much lower levels.

Because the federal estate tax stands at a hefty 40%, there’s plenty of incentive for high-net-worth families to do what they can to lessen its impact. And yet what I’ve found over the years is that, for many people, estate planning falls to the bottom of the to-do list. There’s a number of reasons for this. Chief among them, in my opinion, is the fact that estate planning requires time and mental energy. Because it’s not a routine task, it can seem like a black box, and many people don’t know how to approach it or where to begin.

Fortunately, there are easy ways to get started. Each of the following strategies can be effective in reducing future estate-tax exposure.

Annual gifting. This is the simplest and probably the best-known strategy, but it’s also underestimated. Here’s how it works: In addition to the $12.9 million lifetime exclusion referenced above, tax rules allow additional gifts to be made on an annual basis. This year, the limit for these annual gifts is $17,000. If your assets exceed $13 million, and you’re trying to defray estate taxes, that might not sound like much, but it can be highly effective.

That’s because it’s $17,000 per donor and per recipient. Consider a husband and wife who have three grown children, all married. That’s two donors and six recipients, for a total of 12 potential gifts of $17,000. That adds up to $204,000, and this could be repeated each year. If you’re able to do this for several years, the compounded value of those gifts could be significant.

Paying tuition and medical expenses. The lifetime exclusion has two notable exceptions: Parents or grandparents are permitted to pay any amount of tuition for family members—or anyone else, for that matter—as long as those payments are made directly to the educational institution. This can be an effective way to move six-figure sums out of your estate. A similar exclusion also applies to medical expenses, which also must be paid directly to the medical provider in order to qualify. While you hopefully won’t need to take advantage of the medical expense exclusion, it’s good to keep it in mind.

529 accounts. Many families establish 529 accounts to help fund their children’s education. In many cases, this makes sense. But they may not make sense for the wealthiest families. That’s because, as described above, tuition has its own exclusion, which is unlimited. Consider a set of high-net-worth grandparents with five grandchildren. They could establish 529 accounts, and that would have the benefit of moving assets out of their estate.

The alternative, though, is that they could instead pay all of their grandchildren’s tuition bills directly. If private college costs $80,000 per year, the total tuition bill for the five grandchildren would be $1.6 million ($80,000 x four years x five grandchildren). All of that could be moved out of the grandparents’ estate without any impact on their lifetime or annual exclusions. While 529 accounts do have the benefit of tax-free growth, the resulting estate-tax savings on this $1.6 million could easily outweigh the tax benefit offered by 529s. But like everything in personal finance, the right decision will depend on the particulars of your family and your finances.

Roth conversions. These aren’t normally viewed as an estate tax strategy, but they’re actually one of the easiest and most powerful strategies available. That’s because a Roth conversion triggers an immediate income tax, and that tax will be paid using dollars that otherwise would have been subject to the estate tax at death. Suppose you complete a Roth conversion of $200,000 and pay $50,000 in associated taxes. Assuming a 40% estate tax rate, this move alone would reduce your estate tax burden by $20,000 ($50,000 x 40%).

Changing your residence. Today, some states have their own estate taxes, but most don’t. If your assets top your state’s threshold, you might consider changing your residence to a no-tax state. Note that you can’t simply buy a vacation home and spend 51% of your time there. You need to change your primary residence in a meaningful way.

What else can you do? I contacted an estate-planning expert and asked for his recommendations. Amiel Weinstock is an attorney in Brookline, Massachusetts. He offered a three-part prescription.

First, recognize that estate planning means different things to different people. It isn’t one-size-fits-all, so the most important first step is to assess your own needs. Older folks, especially those with likely estate tax exposure, will want to focus on wealth transfer strategies. That’s where there’s going to be the most leverage. But for families with young children, a basic will and revocable trust may be the most important thing, because these documents will ensure that the right people are in place to care for and manage the assets of any minor children.

Second, Weinstock emphasizes the importance of term-life insurance for those in their working years. “You could have the best estate plan in the world, but you need to be sure your family would have enough to live on.” The two go hand in hand. If you don’t have sufficient insurance, start this process today. Why? “If you get sick, your insurability could change overnight. But you’d still have time to put together an estate plan.”

What if you’re older and facing likely estate tax exposure? Weinstock offers this third recommendation: Don’t view estate planning as an all-or-nothing project. If you haven’t yet taken steps to manage your estate tax exposure, consider implementing just one strategy to start. You could, for example, set up an irrevocable trust and move a handful of assets into it. Then reassess the following year.

This is good advice. In my experience, many wealthy families delay putting strategies in place because the task seems daunting. But it need not be. Bear in mind that asset values tend to rise over time. Result? The best time to get started is, in most cases, today.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Shrink That Estate appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 15, 2023

Guns to Stethoscopes

MY PARENTS WERE products of the Great Depression. Dad was the frugal one. He was also a pack rat. He’d save pieces of wood for that shelf that he would build “someday.” For years, those pieces sat under the ping-pong table in the basement.

One night, Mom dragged the wood out to the street for the garbage collector to haul away. Later that night, Dad dragged the pieces back into the basement. Mom was the type to get rid of things that were no longer needed. I wish I’d taken after Mom. I’m glad, though, that I took after Dad when it came to saving and frugality.

When I was growing up on Long Island, New York, my parents never talked about our family’s financial situation. It seemed like we were lower-middle class. Dad would follow us three kids around the house, turning off lights and tightening bathroom taps. Later, after my parents died, my sister, my brother and I found out that they had more money than we thought. This was true even though both Mom and Dad died during the Great Recession, when the value of their investments was down significantly.

Dad never knew his father, who disappeared during the Depression. We don’t know whether he deserted the family, died or was killed. He likely deserted, leaving his wife and their three young boys to fend for themselves. Dad had a grandfather that filled in, but it made Dad determined to be a good provider for his kids, especially his son.

When I asked Dad if I could go to Columbia or Fordham University, both private institutions, he told me, “No, your brother’s education comes first because he’s a man and someday he will have to support a family.” I guess I can’t complain since he paid for my undergraduate education at the State University of New York at Albany. Still, the message was clear: My education wasn’t as important because I was female.

My mother wanted me to be a secretary, get married, have children and live close by. Instead, after I graduated, I moved 3,000 miles across the country to California and joined the police department.

My father taught me two important financial lessons. First, save, save, save. Second, get a government job because you’ll get a defined benefit pension. Other than that, I didn’t know much. Indeed, at a local bank, I bought class B mutual fund shares, which impose a back-end sales charge when sold. I also funded IRAs starting in 1985, but for years I made the mistake of investing my IRA in bank certificates of deposit. I would have done much better in the S&P 500.

Over time, I learned about financial planning. I followed Jonathan Clements’s column in The Wall Street Journal. I eagerly learned from Warren Buffett. Eventually, I came to appreciate the virtues of index funds and Roth IRAs. Starting in 2002, I converted a significant portion of my traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs. For that, I’m eternally grateful to my younger self.

But there’s one thing I wish my younger self had understood better.

Women had only been accepted into the police department in 1975. I joined in 1980, and the police still weren’t very accepting of women. If I’d washed out of the department quickly, my plan B was to become a paramedic. That would have got me to my current job—to which I’m much better suited—far faster. But at the time, giving up on police work would have felt like a devastating failure. The lesson: Sometimes, failure can be the best thing to happen to you.

After I didn’t make detective, I became bored and wanted another job. I applied to the Peace Corps but was told I had no skills that the Corps could use. I asked what they were looking for and they said medical skills.

As a police officer, I often went to hospitals to interview victims and suspects. I felt comfortable there and was intrigued by all that was going on. It had been a while since I graduated college. At the time, math and science courses weren’t required to graduate. I decided to take beginning math and science courses at the local community college while continuing to work fulltime. It wasn’t easy.

Still, I found that I really liked the course work and it liked me—I was good at it. I transferred to a local four-year college to finish my pre-med courses and, after that, I applied to medical school. By then, I had quit the police department.

At age 41, getting into medical school was difficult. Most schools wouldn’t accept applicants over 30. But there were two University of California schools that had a reputation for being open to “mature” students. One of them accepted me.

I became a medical intern—the first year of my residency—at the University of California, San Diego, at age 45. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Then, at 50, I decided to enter an infectious disease fellowship program back in New York. In hindsight, the benefits I received didn’t justify the hefty costs involved—the lost wages, the hours on call, the humiliation dished out by the “attending” physicians during hospital rounds.

Up until 2010, when I finished my medical training, the most I earned in a year was $60,000. But once I became an attending (or unsupervised) physician myself, my income rose. Even though I’d used most of my savings to pay for medical school, I’d still accumulated $30,000 in student loans—which I was now able to pay off.

Except for the fortuitous Roth conversions, I really didn’t start amassing money for retirement until my late 40s. Since becoming an attending physician, I’ve contributed the maximum to various retirement accounts, as I try to catch up. That’s why it’s so annoying when I hear, “You’re a doctor, you can afford it.”

At age 56, I finally bought my first home. I still have a big mortgage, which I want to pay off before I retire. I’m guessing I’ll be working into my 70s. This year, I also finally treated myself to a new car. Before that, I’d owned just two cars in my life, each one for 20 years.

I never married. It’s hard for a woman to find a man who’s willing to follow her while she pursues her dream career. Typically, it’s the woman who makes the sacrifices. During one 12-year period, I moved eight times. One of my guiding motivations has been the fear that I’d end up as a bag lady living on the street. I’ve always felt that I had to depend on myself.

Still, it’s been difficult as a single woman. Auto mechanics, contractors and salesmen sometimes try to take advantage of you. Employers don’t always pay you fairly or give you the same opportunities as male colleagues.

But with all that, I get a deep sense of satisfaction from my job—because it allows me to provide medical care to those who need it. Today, my practice focuses on general medicine patients, as well as those infected with HIV and COVID-19. Some patients have never been to a doctor before. In a way, these patients are my children. Changing careers to become a doctor was not financially savvy. But it sure has been a salve for my soul.

Kathy Thompson lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area. A transplanted New Yorker, she’s now a Californian at heart. Kathy comments on HumbleDollar as kt2062.

Kathy Thompson lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area. A transplanted New Yorker, she’s now a Californian at heart. Kathy comments on HumbleDollar as kt2062.

The post Guns to Stethoscopes appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Just Being Average

MY FATHER RAISED ME to think that, if I set my mind to it, I could do just about anything. He said that concentrated focus and drive would allow me to reach my dreams, and that there was rarely a time when I should settle for average.

Maybe it’s no great surprise, then, that I hate being average. I’m above average in smarts, the kind that gets you a side order of noogies as a second grader. Luckily, I’m also above average athletically—or fancied I was until I hit middle age. This helped avert a number of swirlies in junior high. If you’re not familiar with swirlies, count your blessings.

The pendulum, of course, swings in both directions. I’ve always been below average in certain ways. Such as height. It’s not so bad. I make up for it in width and depth. I didn’t hit five feet until my freshman year of college. Good for me that I kept growing, at least for a little while longer.

Still, my father taught me to be average in one special way, an exception to his other teachings. He recommended that I have average expectations for financial market returns, and that I use that “average” mentality as the basis for my long-term investment strategy.

He also had three specific pieces of advice. First, live below your means. Second, automate savings so those savings are sure to happen, rather than waiting to see what’s left over after paying that month’s bills. And, most important, invest your long-term holdings in a solid fund that mimics the entire stock market.

In my 30s, I spent time chasing returns. I would discuss some of my stock picks with my father. He always listened patiently and asked why I chose this or that company. He wanted me to describe my rationale for buying and selling. He never criticized my investment choices, but he did highlight the need for due diligence.

Overall, my stock picks didn’t prove to be winners. I was just buying on hunches. I didn’t have a solid plan, instead making purchases based on hype and news without knowing the full context.

Eventually, it dawned on me that—by the time information reached me—it was already past the point where it offered any advantage. More often than not, I caught a stock just before its peak and ended up selling in time to capture significant losses. Economist Eugene F. Fama has described the market as “informationally efficient,” meaning all available information regarding the current and future state of a company is fully reflected in its share price.

It’s incredibly easy to underperform by chasing dreams. It’s incredibly hard to pick the next Apple or Amazon. It’s nearly impossible to outperform trained professionals.

Another of my father’s little secrets: “Simplicity is the master key to financial success,” he’d say. For most of the past three decades, I’ve stuck to this philosophy.

I came across my father’s little secret while reading a classic by John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing. Most know Bogle as Vanguard Group’s founder. He’s also remembered as the creator of the first index mutual fund. Rather than owning a piece of the market, he advocated investing in the entire market through a low-cost index fund.

Long-term investors can achieve success by matching, not beating, the market. It’s insanely simple to match the market’s return, minus some small sliver for expenses. The patient investor can capture the hopes and dreams of a noisy market just by standing still. All you have to do is be humble, and tell your ego that it’s okay to accept the market’s average return.

Although I’ll never know for sure, my guess is that Dad read Jack Bogle’s writing and took his ideas to heart. I also have a sneaking suspicion that my father was a Boglehead, the community of investors inspired by Bogle’s philosophy. Even if he never said it, Dad followed their investment practices.

I’m now entering retirement, leaving a career where my goal was to be anything but average. I’m confident that my retirement will be financially stress-free because I adhered to a few simple edicts that my father taught me early on—including knowing it’s okay to be average when investing.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. His previous article was Wisdom of My Father.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. His previous article was Wisdom of My Father.

The post Just Being Average appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 14, 2023

All My Children

ONE OF THE CLEARER mandates for a Christian such as myself is to help the poor. Jesus said the poor “will always be with you.” It doesn’t take amazing powers of observation to see that he was correct. There are lots of ways to help the poor, with churches and thousands of worthy charitable institutions working to address the causes and effects of poverty.

Many years ago, I became acquainted with a large Christian organization called Compassion International. Starting in college, I’ve sponsored children through Compassion for almost 40 years. In all, I’ve sponsored 18 children from 12 countries. Sponsorship involves sending a monthly support amount, currently $43 per child. The support is used for such things as educational supplies, basic preventive health care and nutritious meals at the project center. You can also send special gifts for birthdays and Christmas. Generally, sponsors will get several letters a year from their sponsored child, and sponsors can also write to their child at any time.

Let me tell you just three of my kids’ stories.

Jimmy from the Philippines was the first child I sponsored, starting in my senior year of college. He was 10 years old at the time and would write me letters in English. Some of his letters were fairly long and detailed and, after exchanging letters over the course of nine years, I felt I knew him quite well. He was described as a friendly, cheerful boy in one of the reports I received from Compassion.

In his letters, Jimmy would mention personal details about his life. One time, he wrote, “Let me share to you my unforgettable experience. This happened when I was selected to be a worship leader in our church. Since it is my first time, I was so nervous. My T-shirt became wet because of my perspiration.” Reading his letter, I could almost feel his teenage tension. It’s hard for me to picture him as the 50-year-old man he would be today.

Sango lived in Zaire, now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which experienced a huge civil war 10 years into my sponsorship. She lived in poor conditions and didn’t have access to good water. Her father was dead. She was amazed by the small gift she received for Christmas, which perhaps had disproportionate impact due to her family’s poverty. Sadly, Compassion’s work in Zaire was upended by the war, and the ministry lost track of her. I pray that she survived, but have no way of knowing.

I sponsored Ramon from the Dominican Republic for 14 years. He wrote me gracious letters and was grateful for the opportunities that sponsorship afforded him. Around age 23, he graduated from the program. I never expected to hear from him or about him again.

But seven years after he left the program, I received an unusual letter from Compassion. It stated that Ramon had expressed an interest in getting in touch with me. There also were numerous cautions about the potential pitfalls of doing so. I created a dedicated email address for Ramon and gave my permission for it to be sent to him. Somewhat surprisingly, he never emailed me.

A few years after that, I received a Facebook friend request from Ramon. We connected and have been in contact through that platform ever since. He has gone on to obtain a graduate degree and holds an important position in his country’s education system. He has 5,000 Facebook friends and it’s obvious that many people love him. He’s married with three lovely daughters, and also helps pastor a church, presumably in his “spare” time. During the COVID-19 crisis, he contacted me to make sure Lisa and I were okay.

As I understand my Bible, giving should be a source of joy for the giver and an expression of gratitude to God, as well as a way to demonstrate the priority God gives to helping the poor. Nowhere do I get the impression that giving is designed to guarantee me prosperity or to enrich a select few televangelists.

I do enjoy giving to my church and have complete confidence in the handling of the budget there. The deepest joy in my giving journey, however, has been through child sponsorship. How could I put a value on the privilege of helping and befriending 18 at-risk children? I’m no theologian, but I like the sound of Jesus’s words in the Gospel of Luke: “Use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.”

What are your favorite charities? Offer your thoughts in HumbleDollar’s Voices section.

Ken Cutler lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and has worked as an electrical engineer in the nuclear power industry for more than 38 years. There, he has become an informal financial advisor for many of his coworkers. Ken is involved in his church, enjoys traveling and hiking with his wife Lisa, is a shortwave radio hobbyist, and has a soft spot for cats and dogs. Check out Ken's earlier articles.

Ken Cutler lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and has worked as an electrical engineer in the nuclear power industry for more than 38 years. There, he has become an informal financial advisor for many of his coworkers. Ken is involved in his church, enjoys traveling and hiking with his wife Lisa, is a shortwave radio hobbyist, and has a soft spot for cats and dogs. Check out Ken's earlier articles.The post All My Children appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Beer to Taxes

I DON’T FIT THE USUAL profile of a HumbleDollar reader. I don’t have what I’d consider a high net worth, nor am I a college graduate. Still, I hope my story shows it’s possible to reinvent yourself.

Around 1920, my dad’s family moved—with few belongings but a willingness to work—from Tennessee to northwestern Ohio. My dad met my mom while working at Hostess Bakery, and he later worked at Willys-Overland, welding together Jeeps during World War II. I was born a decade later, in 1952.

I remember my dad coming home from work on Friday, after stopping at the bank to cash his paycheck. He and Mom would get out the Dome Budget book to prioritize which biller got what. Still, the first allocation was always a deposit to their savings account.

My generation was the first to grow up with TV. During Saturday morning cartoons, we kids were inundated with toy commercials. I remember telling my dad that I wished I could have this or that toy of the week. My dad’s colorful answer is something I carry with me to this day: “Well, Dan, shit in one hand and wish in the other, then tell me which one fills up first.”

My first job, at age 16, was as a bag boy at a local supermarket. Eventually, I worked in the beverage department, and I used my connections there to get a job, first with a soft drink distributor and later with a beer distributor. I’d also been going to college to pursue a business degree. But I never cared much for school, and I was earning more than my college-graduate friends. I let those two facts justify one of my life’s worst decisions: dropping out of college.

For 30 years, I worked hard on the beer truck and earned a good middle-class income. Of course, the income of my college-graduate friends eventually eclipsed my wages as a driver-salesman. So much for my justification for quitting school.

I always had this thing about numbers—and about money and saving. In 1984, Money magazine published an issue with a fill-in-the-blanks exercise to help readers determine if they were on track to retire when they wanted and with enough money. I did the exercise and became hooked on retirement planning.

Three decades into my career, two things happened that changed my life: one involving my marriage and the other my job.

My wife and I got divorced after 25 years of marriage and after raising two amazing daughters. We split our assets equally and went our separate ways. I was ordered to pay spousal support, which continues to this day.

Meanwhile, the pain of job-related arthritis became more frequent, and plantar fasciitis had set in as well. I felt like I was on the verge of total disability, so I left the beer business behind.

One son-in-law, who happens to be a financial planner, was impressed with my knowledge of his world. He encouraged me to become a registered representative. I studied for and passed the various exams for the life insurance, health insurance and Series 6 licenses.

This did not work out well for me. The main goal of the company I joined was to sell insurance products, such as variable annuities and variable universal life insurance contracts. Don’t get me wrong: I like annuities and life insurance. But when you add that word “variable,” you lose me. Those variable insurance products have killer high fees and, in my opinion, aren’t suitable for most people. I just couldn’t sell them, so I left.

Life took two more turns. In my time as a beer-truck driver, I’d picked up rather unlikely skills. I became active in the union, and I was doing all its financial reporting to the Department of Labor and the IRS, and also handling payroll.

After leaving the insurance company, I began preparing income-tax returns to make ends meet. It turned out that I was good at it, and friends I’d made while selling insurance began sending me clients—lots of clients. I was a one-man shop with low overhead. I had about 650 clients when I sold the practice in 2022─the year I turned 70─to a buyer who was both a tax attorney and a CPA.

Meanwhile, after my divorce, I was middle-aged and unsure about my future marital status. I became analytical about the type of person I’d want as a romantic partner. She would be an intelligent and independent woman who didn’t need a man to survive, and someone who shared my philosophy regarding saving and spending.

I figured I’d remain single for a long time. I was wrong again.

A few years into single life, I bought a house and became fast friends with a neighbor, Chris. She worked for an accounting firm, so we had a financial background in common. Turns out that we checked each other’s boxes. That was 21 years ago, and our relationship remains awesome.

With the combining of our lives came economies of scale. Still, we didn’t change our lifestyle. Instead, Chris began contributing 20% of her income to her 401(k) and maxing out an IRA. I was maxing out my SEP-IRA, IRA and health savings account. Both Chris and I were piling up regular taxable account savings as well. We’ve achieved our goal of a seven-figure net worth, and that doesn’t include home equity.

Chris retired at 64 and began her Social Security benefit. I started Social Security when I sold my business last year. Because I waited until 70, my benefit is some $50,000 a year. Chris’s amount is about $25,000 a year. With our home and cars paid off, and no consumer debt, we live well on our Social Security benefits alone.

What to do with our savings? I admit I struggle with how much I can safely give away. I’m making progress by donating automatically and monthly. I have a handful of charities I support, such as St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, the USO—short for United Service Organizations—and public media.

Now that I no longer have earned income and am older than 65, I could file a motion to have the spousal support I still pay reduced to zero. But if I did, my daughters and their husbands would have to help their mother financially. That’s not a burden that I want them to shoulder. Instead, I’ll pay spousal support for as long as possible. At least I get to deduct the alimony on Form 1040. It’s also my goal to leave a sufficient sum to the kids so they can continue to take care of their mom.

As I enter the foothills of old age, I just want my kids and seven grandkids to know how much they’re loved and to be happy. I hope that they’re able to learn from my experiences—both the hits and the misses.

For 30 years, Dan Smith was a driver-salesman and local union representative, before building a successful income-tax practice in Toledo, Ohio. He retired in 2022. Dan has two beautiful daughters, two loving sons-in-law and seven grandchildren. He and Chris, the love of his life, have been together for two great decades and counting.

For 30 years, Dan Smith was a driver-salesman and local union representative, before building a successful income-tax practice in Toledo, Ohio. He retired in 2022. Dan has two beautiful daughters, two loving sons-in-law and seven grandchildren. He and Chris, the love of his life, have been together for two great decades and counting.

The post Beer to Taxes appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 13, 2023

Paying Those Premiums

I'M 64 AND PREPARING to sign up for Medicare next year. I’ve done extensive research, including earning the Retirement Income Certified Professional designation. I’ve also written articles for HumbleDollar on Medicare coverage, Medicare premiums, Medigap and health savings accounts.

In addition, I’ve befriended Medigap salespeople, advised others on which plans to choose, and asked those on Medicare for advice on their experience with the program. I feel as if I’ve been preparing to take the Medicare filing “exam,” and I’m excited to sign up.

I plan on enrolling in traditional Medicare—Part A hospital insurance, Part B doctor services and outpatient coverage, and Part D prescription drug coverage. I’m also purchasing Medigap Plan G, which will pay for my medical expenses after I’ve met my annual deductible. My planning doesn’t stop there, however.

Once I’m enrolled in Medicare, I’ll no longer be eligible to contribute to my health savings account (HSA). My 65th birthday is next June, so I’ll only be allowed to save in my HSA through May 2024. In 2024, the HSA contribution limit will increase to $4,150 for a solo contributor like me. Because I’m over 55, I can add another $1,000, bringing the annual total to $5,150.

Did you know that allowable HSA contributions are pro-rated in the year you enroll in Medicare? Since I’m only eligible to contribute to the HSA for five months next year, I can contribute 5/12th of $5,150, or $2,145. I’ve got around $25,000 in my HSA already, so my final contribution should bring my balance to around $27,000.

I’m saving all I can in my HSA because it’s arguably the best tax-favored account around. The contributions reduce my taxable income. The account grows tax-deferred. And if I use distributions for qualified medical expenses, there are no taxes owed on my withdrawals.

I’ve learned there’s one drawback to HSAs, however. They’re one of the worst accounts to be inherited by a non-spouse. The entire amount is taxable as ordinary income by the recipient when received. There’s no 10-year distribution period to ease the sting, like there is with inherited IRAs.

For this reason, I’d prefer to spend at least some of my HSA balance earlier rather than later and, indeed, I’m thinking about the period before I file for Social Security at age 70. My Part B premiums and my annual Medicare deductible will both be expenses eligible for tax-free HSA withdrawals. Combined, these should cost me $2,345 in 2024. Unfortunately, Medigap insurance is not an eligible expense for an HSA withdrawal.

The good news is that the Medicare premium surcharges owed by higher earners are considered qualified medical expenses for HSA purposes. Single taxpayers who earned an estimated $102,500 or more in 2022, and married couples who earned $205,000-plus, will be hit with the Part B and Part D surcharge in 2024.

From age 65 through 69, I’ll have to pay my Medicare premiums by writing a check because I won’t be receiving Social Security and hence my premiums can’t be deducted from my monthly benefit. Medicare premiums have been rising around 7% a year, so I expect my premiums will exceed $3,000 a year before I reach 70.

Even if I draw down my HSA by an estimated $15,000 over the next five years, I should have enough left in the account to cover routine medical expenses and, I hope, dental expenses, too. When I file for Social Security, I’ll likely stop paying my Medicare premiums from my HSA. Instead, at that juncture, my Medicare premiums will be deducted directly from my Social Security payments.

After age 70, I could keep track of my annual Medicare premiums or other medical expenses to make further non-taxable HSA withdrawals. Or I could donate the remaining account to charity, so my beneficiaries won’t have to pay ordinary income taxes on what’s left over. But that’s a decision for another day.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.The post Paying Those Premiums appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 12, 2023

Finding Hope

I GOT MARRIED IN 1980 at age 22. After 29 years of marriage, my wife and I went through a contentious divorce in 2009 and 2010. We’d grown apart and, during our last few years of marriage, discussed parting ways.

I moved out of our marital home of 16 years into an apartment. It was strange to be living by myself again. I was 51 at the time.

While adjusting to my new reality, I quickly realized I knew little of our household finances. I was working four jobs to try and help pay down the debt that I’d accumulated when I decided to go back to school in 2003 to become a physician assistant.

Even though I had some vague sense of our debt, I didn’t know how bad our financial situation was. I trusted my wife with all of our finances. I’d grown apathetic after every money conversation turned into an argument. In retrospect, this should have been a warning sign.

Since I wasn’t sleeping well in the months following our separation, I developed a knack for forensic accounting. I quickly learned that my wife had been hiding accounts, credit cards and a post office box from me. In addition, she had forged my signature on checks associated with a maxed-out credit card that I never used.

I discovered that we had a combined debt of $200,000, not including our mortgage. I was embarrassed that I was so out of touch and let things get so out of control. The person in the mirror was to blame—me.

I was struggling both emotionally and financially, and I didn’t know where to turn for financial help. I didn’t have the money to hire someone. Even though I have two graduate degrees, I was never taught anything about personal finance in school or by my parents. This seems to be common in our society. Unfortunately, I also failed to teach my kids the basic principles of personal finance.

Still, my oldest son offered a great suggestion—that I read The Total Money Makeover by Dave Ramsey. The book cost less than $20, it’s a simple and practical read, and it changed my life forever. I finally had a plan to address my debt.

The principles that Ramsey has been teaching for more than three decades are common sense. They’re things that we should all be taught at an early age. But unfortunately, I wasn’t—and it appears neither were many Americans. Household debt by 2022’s fourth quarter totaled $16.9 trillion, equal to almost $129,000 per household.

Since I’m a task-oriented person, Ramsey’s seven baby steps worked well for me. There’s nothing sophisticated about these baby steps:

Save $1,000 for a starter emergency fund.

Pay off all debts except the mortgage using the “debt snowball”—pay off the smallest debt first, then double down on the next smallest, all the while paying the minimum on the rest.

Save three to six months of expenses in an emergency fund.

Invest 15% of your total household income for retirement.

Save for your children’s college in a 529 or similar account.

Pay off your mortgage early.

Build wealth and give.

From 2009 to 2012, I paid off my part of the marital debt, which came to $75,000 after mediation. Both my attorney and the mediator were amazed at how much debt I’d paid off even before the mediation. I did it by working multiple jobs while living as inexpensively as possible. I also continued to give money to my daughter every month while she was in college, and to pay my attorney fees. I moved back into my house in the fall of 2010 and sold it in 2014.

I did my debt-free scream on the The Ramsey Show in 2012 to celebrate my debt freedom and to thank Ramsey in person for changing my life. Some people criticize Ramsey for making money on his debt freedom plan and the products that he sells. I disagree.

My total cost for his help in 2009 was less than $20. His podcasts are free. It seems that this criticism could be directed at any small business owner who took a simple idea and profited from it. But isn’t that part of the American dream?

My current wife of more than 10 years and I remain debt-free. She was raised with much more financial common sense than me. We continue to follow the same financial and investing principles that I started following in 2009. I don't recall us ever arguing about money or bills. We don't owe anybody any money, we can be generous with our giving and we travel around the world.

I debated for a long time whether or not to share my story. After much thought, I decided to write about my experience in the hope that it’ll give someone facing similar circumstances the chance for a better future. When I was 51, my net worth was a negative $400,000 between the mortgage and other debts. My situation felt so hopeless. Now, at 65, I’m no longer hopeless and haven’t felt that way in years.

Scott Martin is a semi-retired family medicine physician associate (previously known as a physician assistant) and has been practicing medicine for the past 18 years. His previous career was in academia doing research and teaching at the University of Georgia. He and his wife enjoy traveling and spending time with family. Check out Scott's earlier articles.

Scott Martin is a semi-retired family medicine physician associate (previously known as a physician assistant) and has been practicing medicine for the past 18 years. His previous career was in academia doing research and teaching at the University of Georgia. He and his wife enjoy traveling and spending time with family. Check out Scott's earlier articles.The post Finding Hope appeared first on HumbleDollar.

An Early Start

WHEN I WAS AGE SEVEN or eight, I had a glass piggybank where I saved all the small change that came my way. I loved the sight of all this money that I could save or spend as I pleased.

One day, my mom needed to go to the grocery store for some bread and found she didn’t have enough cash. She asked to borrow from my almost-full bank. I gave the money to her, after securing a promise that she’d pay it back. She did so. That experience taught me that having some savings could come in handy.

Indeed, I was an avid saver from the time I started getting a paycheck. My first job was during high school, when I was a part-time admissions clerk at a hospital. After community college, I became a dental assistant, which was my first fulltime job. For a few years, I had a number of temporary administrative jobs, as I explored work outside of dentistry. But I went back to being a dental assistant in 1976. That helped me to survive financially during my 1978 divorce from my first husband.

In the mid-1970s, banks started offering IRAs, and it seemed like the perfect vehicle for setting aside funds for my future self. Almost every year after that, I made sure to contribute the maximum amount allowed.

After I met my second—and last—husband, we bought a 68-foot sailboat, which we lived on for the first few years of our marriage. In 1986, we decided to take the boat on what turned out to be an 18-month trip to Mexico. That meant we didn’t work for a long stretch, but the experiences we had were so memorable that I wouldn’t trade that time for anything.

By the time we returned to the U.S., we were broke and had to go back to work. I started reading up on investing, and that’s when I realized that we had to save a hefty sum to supplement Social Security. I started tracking my expenses in a small notebook and created a budget for myself. After I went to work as a fiscal analyst and administrator for California State University, Long Beach, I got even more serious about saving.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1988, my husband and I started investing in rental real estate in northwest Montana. At the time, my husband was an avid skier, and the town we visited had—and still has—a wonderful ski resort. During his 30s, before I met him, he decided to take some extended time off to be a “ski bum.” But even as a ski bum, he noticed the crucial role played by rental properties in the many ski towns he visited across the western U.S.

After we started acquiring Montana rental properties, we made the drive—and occasional flight—from California every six to eight weeks to check on our properties and to make periodic repairs. It was time-consuming, but we looked at these trips as necessary for our future retirement.

I ended up retiring early, at age 50, when we moved to Montana fulltime to look after the real estate. Fifteen years later, at age 65, I took a serious look at my retirement stash and was pleasantly surprised by my account balances. TIAA-CREF, the company that oversaw the university’s employee retirement funds, does a great job of offering a variety of investment vehicles, including both stock funds and stable-value funds. That year, I annuitized all my TIAA-CREF funds, turning them into a monthly payment that I’ll receive for the rest of my life.

I waited until age 70 to claim Social Security based on my own earnings record, after enjoying my spousal benefit for a few years. This option—getting spousal benefits first and then a benefit based on your own earnings record—is, unfortunately, no longer available to retirees.

We started selling off some of the rental real estate several years ago, though we still own six rental units. My husband was getting tired of dealing with the work involved. He also had some health issues. That was a reminder that we’d bought the properties for our “golden” years and—surprise, surprise—we were now there.

Even though I never made a lot of money during my working years, the fact that I started saving so young meant I got a lot of help from compounding. Now, at age 74, I think the most important thing I can tell young people is to start saving early and then leave your money to grow. When you reach retirement, you’ll thank your younger self.

Born and raised in Southern California, Judy Brassaw and her husband moved to Montana two decades ago. Now a semi-retired property manager, Judy enjoys tending to her flowers, reading and bird watching near Flathead Lake.

Born and raised in Southern California, Judy Brassaw and her husband moved to Montana two decades ago. Now a semi-retired property manager, Judy enjoys tending to her flowers, reading and bird watching near Flathead Lake.

The post An Early Start appeared first on HumbleDollar.