Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 122

September 22, 2023

Look Under the Hood

I'M NOT A MARKET addict. How can I be so sure? Because, on many occasions, I’ve been able to stop myself from trading excessively. Still, in July, the stars aligned to make me susceptible to another relapse.

A reluctant traveler at best, I was persuaded to accompany my wife Alberta to a 14-day writers’ conference in Upstate New York. I’m a confirmed introvert, so I groove on alone time. But 10 hours every day—while Alberta attended the conference—proved to be a challenge.

Predictably, the extended ennui triggered my old trading symptoms. Why not embellish my long-term exchange-traded fund (ETF) portfolio with 5% positions in both a racy artificial intelligence (AI) fund and a bet on the expected explosion in the world’s elderly population? I temporarily surrendered to impulse. But fortuitously, the results of my research argued for abstinence.

Marketing is merely slick advertising. At one time, cars driven past their prime were called used. But as auto dealerships’ flapping red banners loudly proclaim, those smooth-talking salesmen are now pushing “pre-owned” cars.

Stock investors are no less susceptible to such flimflam. In fact, they may be more vulnerable, since most car shoppers enter the fray a tad suspicious. By contrast, the person considering a stock purchase may assume she’s protected by government regulation and the financial community’s cleverly crafted image as a trustworthy steward of her money.

Latecomers to the dot-com craze 25 years ago were fleeced by non-tech startups branded with high-tech names. More recently, the Long Island Iced Tea Corp. reinvented itself as the Long Blockchain Corp. in 2017, despite having no blockchain activities. Its stock soared more than 300% following the announcement, only to crater soon after. The microcap stock was delisted in 2021 for “taking advantage of investor interest in blockchain technology.”

Years of stepped-up federal and industry oversight haven’t prevented such chicanery from extending to mutual funds and ETFs. A recent case in point: the proliferation of ETFs offering participation in the robotic and AI frenzy. But how much exposure to the theme do such funds really provide? Take the Global X Artificial Intelligence & Technology ETF (symbol: AIQ). All of its top 10 holdings—accounting for 32% of the fund’s assets—qualify as mega-cap stocks, including Apple, Intel and Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook).

You might recall Carolyn Lynch’s discovery of the ingeniously designed display of L’eggs hosiery. Her husband, celebrated Fidelity Magellan Fund manager Peter Lynch, relates in his 1989 bestselling book One Up on Wall Street how Hanes’s small company size influenced his decision to invest in the manufacturer. Profits from what became one of the most successful consumer product launches of the 1970s would significantly impact the company’s bottom line. By contrast, just how much can AI contribute to the earnings of today’s technology behemoths?

On a hunch, I pulled the relevant information for Vanguard Group’s Information Technology ETF (VGT). Many of the largest positions in the Global X ETF figured prominently in the Vanguard ETF with its broader tech mandate. But despite the spectacular move in AI stocks in the first half of this year, the average annual return of the AI fund over the three years through Aug. 31 was only 6.3%. The corresponding figure for Vanguard Technology was 11.5%.

On top of that, the tiny 0.1% annual expense ratio at Vanguard makes Global X’s 0.68% look prohibitive. I already have enough technology through my broad-based ETFs. The upshot: I took a pass on the Global X fund.

Undaunted by my AI frustration, I searched for ETFs investing in companies that could benefit from the anticipated surge in the elderly population. I could find only one fund easily accessible to U.S. citizens, the Global X Aging Population ETF (AGNG). Hey, I’m really not trying to single out the creative Global X management team for its sorry practices, which are widespread among other fund families. Its offerings are among the most forward-looking in the ETF sphere. But sometimes, the rush to attract investors can invite excess.

The Global X ETF has been promoted as capturing the investment opportunities presented by the world’s aging population. But it’s not innovative at all. It’s merely a stealth health care fund, and a poor substitute at that. Why do I think so? All of the fund’s top 10 holdings are related to medicine. In fact, a staggering 93% of the fund’s portfolio is invested in companies engaged in some aspect of health care. Likewise, its 0.5% annual expense ratio compares unfavorably to the 0.1% cost of the Vanguard Health Care ETF (VHT).

According to Morningstar, the three-year average annual results for Global X Aging and Vanguard Health Care were 2.6% and 7%, respectively. In addition, the Vanguard fund’s maximum drawdown in the last three years was much lower, sealing the deal. I don’t need another health fund masquerading as something more exotic.

“What’s in a name?” Not always what the marketing arms of the country’s leading fund management companies would have us believe. Long-term investors with an itch to trade around the edges of their portfolio, and short-termers craving the latest market darlings, would do well to look under the hood.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

The post Look Under the Hood appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 21, 2023

Driven by Data

THE SUMMER AFTER MY sophomore year at Virginia Tech, I had an internship with Frito-Lay, working in its computer applications department at the company’s research headquarters in Irving, Texas. One of the programs I had to learn was VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet program for personal computers. This was my introduction to spreadsheets, and I’ve been hooked ever since.

Sometimes, I joke with my family that I live the data-driven life—not to be confused with Rick Warren's purpose-driven life. I have Excel spreadsheet workbooks for just about everything.

Here’s just some of my workbook titles: books, budget, car maintenance, children, Christmas cards, fitness and nutrition, giving, home projects, letters to the editor, meal ideas, ministry management, people, retirement, vacations and Wordscapes. My most recent workbook is entitled HumbleDollar.

In my career, I’ve used spreadsheets to help manage all of my major work projects. Some of the workbooks associated with larger projects contain 30 or more spreadsheets, with each sheet dedicated to a different aspect of the project. But I’m guessing that HumbleDollar readers wouldn’t be terribly interested in a detailed technical explanation of how I manage nuclear power plant projects using these workbooks.

At home, my most sophisticated workbook is called finances. It’s evolved over the past quarter-century, with each annual edition incorporating incremental improvements. It contains 20 separate spreadsheets, each with a different purpose. The most important spreadsheet is entitled financial summary. It lists all our assets by account and fund, totaling them up to provide a net worth. Home equity is included in the net worth calculation, but there’s also a sub-calculation that includes only financial accounts. The value of my pension isn’t included in either the net worth or financial account calculations, but it is included in a total asset calculation.

A spreadsheet called portfolio analysis pulls data from the financial summary workbook. In that spreadsheet, financial assets are binned across various categories, such as large-cap U.S. stocks, international stocks, Series I savings bonds and money market funds. A percentage is calculated for each category. This allows me to see a detailed breakdown of the overall allocation of our entire portfolio.

Other data calculated on the portfolio analysis spreadsheet include such things as year-to-date portfolio percentage change, stock and bond allocation for the entire portfolio, stock and bond allocation for retirement accounts only, and year-to-date percentage change for our combined Roth IRAs.

I use the chart feature as well. One of the spreadsheets is labelled total financial resources. Using data going back to 2002, it includes a chart that displays the growth over time of our Roth IRAs, our miscellaneous fund portfolio, my 401(k) and our total portfolio.

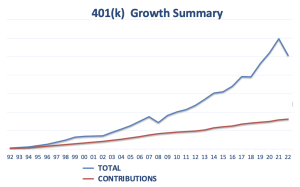

I also use the chart feature in a spreadsheet called 401(k) growth. You can see what it looks like in the accompanying chart. In this spreadsheet, I track a performance indicator I call “percent contributions.” It’s a simple calculation of what percentage of my total 401(k) balance can be attributed solely to contributions I’ve made. Lower is better.

I also use the chart feature in a spreadsheet called 401(k) growth. You can see what it looks like in the accompanying chart. In this spreadsheet, I track a performance indicator I call “percent contributions.” It’s a simple calculation of what percentage of my total 401(k) balance can be attributed solely to contributions I’ve made. Lower is better.

In 1992, the first year for which I have data, contributions stood at 67.3% of the balance. As of year-end 2022, it was down to 31.9%. It’s been as low as 26.5%. Had I made significant 401(k) contributions early in my career, the percentage would be even lower.

A number of years ago, it dawned on me that my spreadsheet data are among my most valuable possessions. Losing this information would be catastrophic to me, so once or twice a year I back up all of my workbooks to a thumb drive, which I then place in our safe deposit box. I’d rather not discover what the data-deprived life is like.

The post Driven by Data appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Powerful Savings

I BOUGHT AN EXPENSIVE new water heater last year for my house in Maine. The old heater had a ring of rust at the bottom, and I was spurred to act by an $800 rebate offered by the state of Maine, which was contingent on buying a heat pump water heater. The new water heater draws its heat from the surrounding air, and is two-to-three times more efficient than my earlier model.

I filled out a rebate form at the appliance store counter. Months later, I got a curt email from the state of Maine saying I didn’t qualify for money back because the model I’d purchased wasn’t Energy Star rated. By then, the heater had already been installed and I didn’t want to unwind the purchase. Lesson learned: Read the fine print.

That’s good advice if you want a share of the billions in energy-efficiency tax credits contained in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act. From now until year-end 2032, homeowners can get money back after installing energy-efficient heaters, windows, doors, air-conditioners, furnaces, water heaters and more. Although these energy-efficiency incentives could return $28 billion to taxpayers, according to an estimate from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, most taxpayers haven’t heard of them.

In past years, you may have used similar tax credits to snag a deduction for new windows and doors. In many cases, the new law is an extension of previous schemes, but with more generous allowances. Some are for energy savings, like insulation, and others are for energy creation, like solar panels.

There’s fine print you’ll need to understand to make sure you qualify, which I’ll cover in a minute. To whet your appetite, here are 10 credits that may cut your utility bills—and your taxes, too.

1. Insulation. The government will pay 30% of an insulation project’s cost, covering up to $1,200 a year with tax credits. A tax credit is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in the federal income taxes you owe. All these credits are offered annually, meaning you could stage several improvements through the years, until the credits end Dec. 31, 2032.

2. Windows and skylights. The government will pay as much as 30% of a window replacement project’s cost through tax credits worth up to $600 a year. The replacement windows must meet Energy Star’s most efficient rating, which means they’ve been tested to meet certain energy-saving standards.

3. Heat pump water heaters. You can get back 30% of the project’s cost, up to $2,000 in tax credits, for installing these energy-efficient water heaters. That credit, plus the state rebate, might pay for the entire cost of buying and installing one in Maine, but only if it meets the Energy Star efficiency rating.

4. Geothermal heat pumps. You can get a 30% tax credit on the cost of installing one of these systems that uses the ground or groundwater to heat or cool a residence. The unit must be Energy Star certified. The credit will decline to 26% of the project’s cost in 2033 and 22% in 2034.

5. Small residential wind turbines. You can get a 30% tax credit before Jan. 1, 2033, on the cost of installing a small windmill that converts wind power to electricity compatible with your home’s electrical system. The credit will decline to 26% in 2033 and 22% in 2034.

6. Solar panels and solar water heaters. Again, you can get a 30% tax credit before Jan. 1, 2033, on the cost of installing solar panels or a solar water heater. The credit will decline to 26% in 2033 and 22% in 2034. Unusually, both principal residences and second homes qualify for the solar panel and solar water heater credits. The installed water heating system must be certified by the Solar Rating and Certification Corp.

7. Electrical panel upgrade. If your fuse box needs to be juiced up to accommodate one of these new energy systems, 30% of the project’s cost, up to $600, will be refunded through a federal tax credit. The new box has to have at least 200 amps and meet the National Electric Code.

8. Home energy audit. Taxpayers can claim 30% of the cost, up to $150, in the form of a federal tax credit on a written energy audit conducted and prepared by a certified home energy auditor.

9. Battery storage. If you want a battery to capture the power created by a solar panel, windmill or similar system, you can get 30% of the cost back in a federal tax credit for installing a residential fuel cell. The credit will decline to 26% of the cost in 2033 and 22% in 2034. The unit must have a storage of at least three kilowatts, and both primary and secondary residences qualify.

10. Air source heat pumps, including mini-splits. You can get back up to 30% of the cost of an air source heat pump to heat your house, up to a maximum of $2,000 a year. The qualifying brand of heat pump varies by region. You can find details on the Energy Star website.

There are several more credits available on central air-conditioners, boilers, furnaces and biomass fuel stoves. I frankly don’t understand the ins and outs of all these newer systems, or who they’re best suited for. I can tell you, however, to understand the fine print in the tax code before acting.

One roadblock to getting money back is that the energy tax credits are nonrefundable. You can’t receive the full credit unless you’d otherwise owe the IRS at least as much in taxes. A second limitation: The maximum tax credit a homeowner can receive for these energy improvements is $3,200 a year. You might want to stagger projects so you don’t exceed this ceiling in any one year.

The cap is lower still on specific projects like new exterior windows and skylights—30% of the cost up to a maximum of $600 a year. If you spent $2,000 on new windows in one year, you’d get the maximum annual credit, and further spending on windows that year wouldn’t garner any additional tax benefit. You might want to do one room and then call the window company back to do another room the next year. A similar credit on exterior doors is capped at $250 per door, up to a maximum of $500 annually.

Many of these credits, for such things as windows, doors and insulation, apply to your principal residence only—the place where you live most of the time. Some, such as solar panels and solar water heaters, apply to secondary homes as well, but the credit is pro-rated based on the amount of time spent there. The household energy-saver credits do not apply to rental homes.

These household energy-saver tax credits also don’t apply to places of business. If you work from home, however, you can get the full tax credit if the business use of your primary residence doesn’t exceed 20%. If it does, the credits are pro-rated.

With so many energy credits on offer, you might want to prioritize projects by their effectiveness at lowering your utility costs. Fattening the insulation batts in your attic may save you more—at far less cost—than replacing all your windows. Begin with a home energy audit to learn which projects would be most effective. You can get a tax credit of up to 30% of the cost of the audit, up to a maximum of $150.

I expect the cost of these energy-saving systems will climb as demand for them heats up. Early movers may beat price rises and also sidestep those dreaded “supply chain issues.”

Finally, to claim the credits, you must file IRS Form 5695 with your federal tax return. The government says to claim the credit for the year in which the energy-saving device is installed, not when it’s purchased.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.The post Powerful Savings appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 20, 2023

The Write Stuff

I'VE BEEN SAVING almost my entire adult life. Early on, three books put me on the path to financial success, helping me to reevaluate how I was living.

The first was The Automatic Millionaire by David Bach. This introduced me to the concept that small, automated savings could lead to big results, thanks to compounding over long periods. Albert Einstein reportedly said, “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn't, pays it.” While some people question whether Einstein said this, Bach’s book put the truth of this concept into focus for me.

Dave Ramsey’s The Total Money Makeover provided a step-by-step plan for achieving my long-term goals. His seven baby steps offered a path that almost anyone could follow. He emphasized living well beneath your means, while devoting savings to paying off all debt—except mortgage debt—before then turning to investing.

His principles were a roadmap to financial stability. Paraphrasing Ramsey, live like no one else now so you can live like no one else later. Following his seven baby steps, plus the small changes in daily spending advocated by Bach, would form the foundation of my financial success.

The Millionaire Next Door, by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko, was the most influential of my three early reads. It presents research showing that most wealthy Americans live middle-class lives, preferring a Camry to a Porsche. As a scientist, the book offered data that were analyzed in a way that I could understand. The Millionaire Next Door was proof that, to be affluent, you don’t have to be seen by others as rich.

Instead, what matters is that you’re comfortable with your spending habits, regardless of how others perceive your financial status. The book’s key message: It’s not how much you earn but how much you save that matters most. As Benjamin Franklin reportedly said, "Money makes money. And the money that money makes, makes money."

While I’m grateful to have read these three books when I first started my money journey, I’ll admit to having reservations about wholeheartedly accepting all their ideas as doctrine. The books were a solid starting point for me, a way to whet my appetite for financial knowledge and to formulate my own ideas on wealth management. They do have one deficiency, however.

Following their advice too closely during my early years limited my spending. As I near full retirement, I find myself asking whether my overzealous saving cost me experiences when I was younger.

I want my money to last as long as I do. There’s no expiration date stamped on my foot. Yet I wonder now if I saved too much at the expense of enjoying life. Only time will tell.

What's the best financial book you've ever read? Share your thoughts in HumbleDollar's Voices section.

The post The Write Stuff appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 19, 2023

My Best Experiences

WORD ON THE STREET is that, if you want to use money to make yourself happy, you should buy experiences rather than things.

In principle, I couldn’t agree more.

There is, however, one kind of experience that I see touted both in the media and on social media that I don’t think reflects money well spent: the expensive family vacation to a distant destination. This status-symbol experience, complete with selfies at ritzy hotels, is supposedly designed to create priceless memories.

Actually, it’s probably about creating an upper-middle-class status statement, and it implies that the best memories have to be bought at a high price and created in the artificial environment of PF Chang's and the Marriott. To my mind, this type of experience also introduces kids to a sanitized version of travel.

I’d like to suggest a different course of action—one that, in my experience, does indeed create priceless lifetime memories.

While my family took road trips to places like Toronto, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., these journeys weren’t the crucible of strong childhood memories. Instead, my most precious memories were formed in a very different way: being with my parents when they were serving others.

After my paternal grandfather died in 1980, my father and I would take the two-hour drive every month to my grandmother’s house. During our trips, my father and I would talk for those two hours. When we arrived, my grandmother would make dinner for us. I would hear about what life had been like during the Great Depression and about my grandfather’s job as a signal maintainer on the Pennsylvania Railroad. We would have my grandmother’s homemade cherry pies.

Then my father and I would clean up and do the dishes together. After dinner, we would help my grandmother with chores, like mowing the lawn or working in the garden. Then the three of us would visit my grandfather’s grave. On the way home, my father and I would talk again, and sometimes we’d also listen to the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.

These trips, while costing practically nothing, bonded my father and me, and taught me about filial duty.

During the summers, my mother took the local census in the suburb where we lived, just outside of Erie, Pennsylvania. By July of each year, she had finished with her initial contacts. She would then start her callbacks. My father would drive her to a particular street and wait while she visited the houses on her list. I would often go along and sit in the backseat and read.

One summer, while we sat parked on shady, treelined streets, I read Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year. When my mother returned to the car, she would sit in the air-conditioning and drink her Dr. Pepper. After she checked her documents, we’d speed off to her next target. I learned from my mother’s attention to detail, persistence and obsession with getting a job done right.

These experiences cost nothing, but they allowed me to see my parents not in some distant hotel lobby, but at their very best.

Does all this mean that I don’t like to travel and don’t think travel memories are important? Not at all. I think they’re so important that they shouldn’t be turned into some sanitized commodity and, indeed, that good parents should send their kids off to discover the world on their own.

When I was 20, I took a leave of absence from the University of Pennsylvania and bought a Eurail Pass and a one-way ticket from New York to London. I spent four months traveling by myself from England all the way to Istanbul and then back to Western Europe. I flew home from Madrid. My parents knew that this kind of adventure would help me to grow and give me unbelievable memories, so they chipped in a few thousand dollars, and told me to get to an embassy and call if I got into trouble. I spent less than $4,000 over those four months.

During the trip, I learned about the world and people. My mouth dropped open as I sat in my cheap Leicester Square theatre seat. The curtains parted, and Timothy Dalton and Vanessa Redgrave stood some 10 feet away. In Cologne, at the Ludwig Museum, I saw Max Ernst’s very funny The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child Before Three Witnesses. A day trip on the train from Barcelona took me to the melting clocks of the Salvador Dali Museum in Figueres.

On the way to Spain, I drove with a French nurse in her pink Lada jeep from Paris through the Pyrenees at sunset. I hung out with an English gypsy named Julian at a hotel on the Greek island of Naxos, where I also rented a motorcycle and cruised around the wildflower-filled fields. On a crappy passenger ship from Brindisi to Patras, I drank beer with a 26-year-old female U.S. Navy dentist, who fell over laughing when I got seasick. “Gotta get those sea legs,” she said.

I hitchhiked through Northern Ireland and caught a ride with an Irish geologist through Belfast. He took me down the Falls Road, the scene of much sectarian strife during the Troubles. A Greek truck driver named Theo gave me a lift to Thessaloniki after I had gotten robbed on the beach. When I was leaving Belgrade, where I stayed with university students in a high-rise flat, I shared a train compartment with three Yugo factory workers, who in turn shared schnaps and fried chicken with me.

I learned that the best travel is exhausting, exhilarating and ennobling, and not all that expensive. It’s not something that should be crammed into a week spent at high-priced hotels, with everyone pretending to have a good time. That’s not money well spent.

My parents created great memories for me by taking me with them when they were being who they really were. The cost? Nothing. They also helped me to create my own memories by supporting me when I wanted to push boundaries and see the world.

Douglas W. Texter is an associate professor of English at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas. Doug teaches a composition I course that focuses on personal finance. His essays and fiction have appeared in venues such as the Chronicle of Higher Education, Utopian Studies, New English Review and The Writers of the Future Anthology. Doug's previous article was Follow Those Values.

Douglas W. Texter is an associate professor of English at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas. Doug teaches a composition I course that focuses on personal finance. His essays and fiction have appeared in venues such as the Chronicle of Higher Education, Utopian Studies, New English Review and The Writers of the Future Anthology. Doug's previous article was Follow Those Values.The post My Best Experiences appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Behave Yourself

SMART GUYS CAN DO some really dumb things. Those dumb things include behavior that seems logical, but is often a sign of addiction.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines addiction as “a compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance, behavior, or activity having harmful physical, psychological, or social effects.” Addictions come in many flavors. Some are benign, some more malignant. Many involve repeating a pattern or behavior in hopes of achieving a different outcome. And yet insanity has been defined as doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result—a comment, incidentally, that’s often wrongly attributed to Albert Einstein.

Addictive actions are sometimes characterized as socially acceptable and sometimes not. An example of a socially approved addiction is excessive intake of coffee, while tobacco use would be placed in the malignant category because it can cause cancer.

Let me share with you two of my addictions. The first borders on malignant, while the other represents a socially acceptable activity that might be benign, but can still be financially ruinous.

I’ve had migraines since I was four years old. Starting in my teens, they occurred at least once a month. The treatment was Tylenol with a dash of codeine. When I began college, the dose was doubled, and a pinch of caffeine was added to the “therapy.” The migraines were manageable, or so I thought.

Fast forward to 2008. I was now married with pre-teen twins and working my tail off as an assistant professor. The pressure to produce research was intense. I was also expected to teach, write grant proposals and supervise graduate students. At the same time, every day brought a new stock market low.

I was smart enough to know that time was on my side in saving for retirement. I also knew that market drops were a great buying opportunity. Still, adding work pressure to a tanking market was a guaranteed recipe for more migraines.

Before long, I realized I was self-administering “preventive” meds every morning to stave off migraines. It was a dumb idea. Really dumb. I tried going cold turkey, but the migraines came back with a vengeance. That’s when I realized I was nurturing an addiction to the pain meds. Luckily, exercise and meditation allowed me to turn things around, but it wasn’t easy—and it remains a challenge to this day.

Meanwhile, three years later, I realized I was forming another type of addictive behavior. It was 2013, a time in the market cycle when the proverbial monkey throwing darts looked like a stock-picking genius. I was trudging along with boring monthly additions to my Vanguard Group growth funds. Day trading was all the rage, and I could hear the mythological call of the siren’s song. I thought to myself: I can do this. After all, I’m a pretty smart guy.

I’d previously completed an internship with a truly brilliant scientist whose work was acquired by a mid-sized pharmaceutical company—a company that was now a Wall Street darling. I noticed heavy trading each day during the first 15 minutes after the market opened. Surely, I could time the dips and make a profit.

I opened an E*Trade account using a small bonus from work, and set a modest goal of earning at least $50 a day trading the company’s stock. For a while, it worked. My bonus money almost doubled in no time. Elated, I started using margin debt to leverage my bets. It was heart-pounding excitement as I watched the ticker move.

Actually, it was an addiction—a smart guy doing a dumb thing. It was the first thing I thought of in the morning, and before long I was placing two or three “bets” a day, trading on nickel and dime share price movements. Problem is, these trades detracted from my work responsibilities, taking time away from my research and diverting mental attention away from my students.

Despite all my trading, I was also blind to the clinical trials that the company had underway. When negative results were announced overnight, my early morning bets were trounced. I lost 60% of my cash pile in a single day. Disgusted at my behavior, I sold it all. My one-time bonus was markedly diminished. Even worse, the stock recovered over the next two months and went on to new highs. Had I just shown the same discipline I display in my retirement accounts—setting it and forgetting it—I would have been fine.

I realized that the day trading had turned into a compulsive and addictive thrill-seeking ride. Yes, it was socially acceptable and hence a benign addiction. But plain and simple, it was gambling.

Some lessons can only be learned via experience. In my case, I take comfort that it was a relatively low-stakes lifetime lesson. In hindsight, I realize I could have used that bonus money to take my family on vacation. Or make an extra couple of mortgage payments. Or put it toward retirement.

Addictive behavior can dull even the sharpest tacks in the box. But at least I was smart enough to recognize a dumb activity—and I learned that the daily thrill wasn’t the way for me to achieve financial success.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. Check out his earlier articles.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. Check out his earlier articles.

The post Behave Yourself appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 18, 2023

That Elusive 1%

EVERY DAY, I READ about the Federal Reserve’s thinking on interest rates—increase, hold, decrease—and the possible impact on the economy. But what about the impact on savers?

As someone who has most of his non-stock monies invested in taxable certificates of deposit, high-yield savings accounts and money market funds, I have a different criterion for the right interest rate: It’s the rate that would give me and other risk-averse savers a modest real return of perhaps 1% a year, after adjusting for inflation and taxes.

Unfortunately, after doing a few simple calculations, I’ve realized that notching this seemingly modest real return requires a rare combination of interest rates, tax rates and inflation rates.

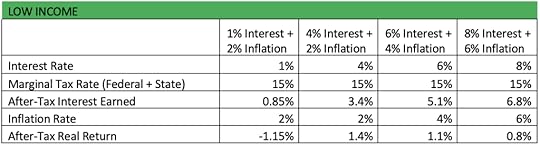

Suppose a couple has “moderate” income—meaning 2023 taxable federal income between $89,450 and $190,750—which puts them in a 22% marginal federal tax rate. If we add an assumed 3% marginal state tax rate, that gives them a 25% total marginal rate. As shown in the table below, our hypothetical couple would achieve a 1% real return if they earned 4% interest with 2% inflation. Think of that as the “Goldilocks” scenario.

By contrast, with a 1% interest rate and 2% inflation—which was fairly typical pre-pandemic—the real return was quite negative. Hoping higher interest rates will drive that 1% real return? They won’t help if they’re accompanied by correspondingly higher inflation rates, plus taxes are assessed on the nominal interest earned, not inflation-adjusted interest earnings.

Yes, it’s better to have more income than less. Still, with a lower income, your chances of making a 1% or better real return on savings are higher because your marginal tax rate might be just 15%. This 15% assumes a couple has 2023 taxable federal income between $22,000 and $89,450, which would then be assessed at a 12% marginal federal rate, with maybe a 3% state tax rate on top of that.

On the other hand, if you’re fortunate to earn enough to reach the highest marginal tax rates, your chances of earning a 1% real return on savings are pretty low. This is due to a marginal tax rate of 45%-plus. Where does that figure come from? A couple with 2023 taxable federal income of more than $693,750 would face a marginal federal rate of 37%, plus a Medicare investment income surtax of 3.8%, plus an assumed state tax rate of 4%-plus.

The lesson: While everyone’s circumstances differ, in general it takes a decent rate of interest, coupled with a low tax rate and a low inflation rate, to earn a real return on low-risk taxable savings. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t hold cash investments for upcoming expenses and financial emergencies. But you won’t get rich holding your long-term investment money in cash.

After 40 years working for GSK Consumer Healthcare (now called Haleon), Paul Sklar took advantage of a severance opportunity and left the firm in 2022. He now does part-time

consulting as Paul Sklar Consulting LLC. In his spare time, Paul likes to exercise, read and spend time with his adult children.

After 40 years working for GSK Consumer Healthcare (now called Haleon), Paul Sklar took advantage of a severance opportunity and left the firm in 2022. He now does part-time

consulting as Paul Sklar Consulting LLC. In his spare time, Paul likes to exercise, read and spend time with his adult children.

The post That Elusive 1% appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Rise of the Ronin

SAMURAI WERE EMPLOYED by feudal lords in Japan. They were skilled in the art of combat and highly trained—the best of the best.

A ronin—meaning a "drifter" or "wanderer"—was a samurai who’d left his clan, usually when his master died. Upon leaving, he was free to use his skills to seek similar employment elsewhere or even to choose a completely different profession. A ronin then relied entirely on himself and his skills to get by. Most ronin were self-reliant, self-disciplined and very good at whatever they chose to do.

My friend Simon is a modern-day ronin.

Simon used to be like the rest of us, living by the rules and doing what was expected of him: graduating from university, securing a well-paying corporate job, getting married, buying a home, starting a family. He was careful with money—something his parents taught him—living within his means, paying down debt and saving as much as possible, so he could retire comfortably one day.

Things changed for Simon when his older sister became ill and he almost lost her. That experience served to remind Simon about what’s important in his life—his family—and what isn’t, which was spending most of his time working. He realized he was caught in a trap, trading his quality of life for money, and he didn’t want to play that game anymore.

He ran the numbers and calculated that he’d saved up enough money so he could work less and enjoy life on his own terms. He knew that he’d need to keep working to some degree to fund the lifestyle he was accustomed to, but now he could do work he enjoyed without worrying about how to pay the bills.

Because of the retirement assets he’s accumulated and the passive income it generates, Simon doesn’t have to make a lot of money. He just needs enough to cover his entertainment expenses and maybe put a little in savings. Simon can make $40,000 a year and yet have a happier life, one with less stress than his former self suffered while working for a bank making $200,000 a year.

How sweet is that?

Spending more quality time with friends and family, and doing work he loved, became Simon’s big “why.” His “why” gave him the confidence and courage to leave his well-paid corporate job to become a ronin and fend for himself.

His wife was supportive. But when he told his parents and coworkers what he intended to do, they thought he’d lost his mind and was going through a midlife crisis. They said he was crazy to give up what he’d worked so hard for, and it wasn’t going to turn out well for him and his family. But Simon was undeterred by the criticism and used his “why” to push forward with his plan. Today, these same people are in awe of what Simon has accomplished and some are a little envious of how happy he is.

Simon gets to call his own shots. He’s free to pursue work that’s interesting and meaningful to him. He works at multiple jobs at the same time, providing him with financial security and stability. When one source of income dries up or he decides he doesn’t like working there, he just moves on to something better. Having more than one source of income allows Simon to be picky when looking for something new to do, and it gives him more control over how and when he works.

These days, Simon would never do work that he doesn’t like, no matter how much it pays. He chooses how long he’s going to work at a particular place. He chooses when to take time off. He chooses the people he works with and the location he works at. No more brutal commute for him. He won’t tolerate a bad boss or a toxic work environment. While at work, his focus is on the job and learning as much as possible.

The pandemic was a massive trigger event for many workers. Forced isolation gave them a lot of time to think about themselves and the work they do. They realized how precious and short life is, and that it was a mistake to wait till they were retired to do all the fun things they’d planned. They know anything can happen and, if they wait, they could end up being physically unable to do the things they love to do. What if they got sick or their spouse died?

Because of the pandemic, many people decided they no longer wanted to waste their precious life working a stressful job, putting in their time while waiting to retire one day, so they could then be happy. This change in thinking led to the Great Resignation we recently witnessed.

But it’s far from over. I believe after a period of rest and reflection, together with a dose of reality, many of these folks will re-enter the workforce as ronin. These people want to continue to learn and contribute. They want to work for an organization led by someone they admire and for a cause they believe in.

Ronin like Simon don’t want to retire, although they could. They want to keep working, doing what they’re passionate about at their own pace and in jobs where they can call the shots. Quality of life substantially improves for people like Simon, when they’re able to cover their financial needs with both passive income and a paycheck from work they love to do.

Becoming a ronin changed Simon’s life for the better. If he could do it, there’s no reason you couldn’t do it as well. For the record, I’m teaching my kids to become ronin.

If you’d like to learn more about Simon’s story, download the free book I co-authored, Longevity Lifestyle by Design.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He’s the co-author of Longevity Lifestyle by Design,

Retirement Heaven or Hell

and

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to

BoomingEncore.com

. Check out his earlier articles.

Mike Drak is a 38-year veteran of the financial services industry. He’s the co-author of Longevity Lifestyle by Design,

Retirement Heaven or Hell

and

Victory Lap Retirement

. Mike works with his wife, an investment advisor, to help clients design a fulfilling retirement. For more on Mike, head to

BoomingEncore.com

. Check out his earlier articles.The post Rise of the Ronin appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 17, 2023

Stick to the Classics

THERE’S ONLY ONE THING I like more than writing about personal finance, and that’s drinking a salubrious cocktail. When I realized I could combine both, this article almost wrote itself.

Two decades ago, I read the best cocktail book ever written, The Essential Cocktail: The Art of Mixing Perfect Drinks by Dale DeGroff. He thought so highly of my bartending skills that he even inscribed my copy, though that’s a whole other article. One drink stood out, the Negroni, an aperitif, that may be the greatest cocktail ever built over ice. For those teetotalers who don’t know what I’m talking about, it consists of Campari, sweet vermouth and gin, garnished with an orange peel.

The bitterness of the Campari—tempered by the sweet vermouth and with the gin’s kick—stokes the appetite and sharpens the senses, making it the perfect before dinner drink. When I first made it for my wife in early December sometime in the mid-2000s, she referred to it as the “Christmas drink,” due to its Christmassy red hue.

For the next two weeks, every day when I came home from work, she’d demand “make me the Christmas drink” until a few days before Dec. 25, when she declared, “I’m done, it’s played.” Hey, “to every thing there is a season.” Sometimes, the season ends, though we still enjoy one every now and then.

The Negroni, according to DeGroff, “was created in the bar at the Hotel Baglioni in 1925 when Count Camillo Negroni decided the Americano was too tame a drink. He asked for the barman to spike his Americano with a splash of gin” and—voilà—the Negroni was born.

Since 1925, people have been drinking the Negroni. While the 1:1:1 ratio may have been adjusted at the margins—you may want to try a skosh more Campari—the drink stands as a testament to evolution and simplicity. It’s much like grandma’s lasagna, Ted Williams’s eyesight and New York City pizza. Why mess with greatness?

Well, people do. Over the past few years, I’ve noticed a number of bartenders have tried to “improve” on this epitome of perfection.

A year ago, I ordered a Negroni at one of Kansas City’s finer drinking establishments and was rewarded with a drink that just didn’t taste right. When I inquired, the server explained to me that “we don’t use Campari in our restaurant.” To that, I elucidated, “Then, what you served me wasn’t a Negroni.”

When I subsequently explained this tale of woe to a bartender at Kansas City’s second finest drinking establishment, she heartily agreed. But she then served me a Negroni that didn’t have the required Christmassy hue. I was subsequently informed that it was made with blonde vermouth. “What is blonde vermouth?” you may ask. My response: As it’s not sweet vermouth, “Who cares?”

Just last month at the Belmond Hotel in Iguaçu Falls, Brazil, perhaps the best hotel in South America, I was offered a Negroni that—in addition to the essentials—contained Grand Marnier, Drambuie and grapefruit syrup. The server was nice enough to offer me a sample and, well, “No, Obrigado.” Unfortunately, I fear this won’t be the last time someone tries to improve on perfection.

Quite simply, the Negroni has evolved over the past 98 years to be the little bit of heaven that it is. I get that man is always trying to invent a better mousetrap, but can’t we focus our efforts on more important issues, such as merely expensive first class airline travel, mediocre New York Jets football and middle shelf bourbon?

What does this have to do with finance? Over the past 98 years, rational (and humble) investors have come to realize that, much like the Negroni, there are three basic securities: stocks, bonds and cash. And much like the Negroni, some financial bartenders try to “improve” on these classics.

Recently, a financial advisor offered me the opportunity to buy a fund that invested in Texas real estate property tax loans. The fund boasted a steady return that was a little behind the S&P 500, but with less risk. It all seemed very delectable, until I realized it was really just a bond fund, with an expense ratio north of 1%, which was in addition to the advisor’s 1% take. And then it all seemed, well, just a little less appetizing.

Before that, I was almost tempted to invest in securitized fine art via Masterworks. It seemed quite enticing until I realized that the fee structure was a little too opaque. I detailed its excessive bitterness in a prior article.

I mean, what’s next, investing in nickels for their melt value? Never mind. Someone has already attempted to arbitrage that “gold mine.”

When it comes to my finances, much like my cocktails, I prefer to stick with the classics, like a well-built Negroni, a Marlowian Gimlet or a Manhattan on the rocks. I think it’s better for my appetite, constitution and wallet.

The next time you’re in your favorite drinking establishment, after—of course—verifying the ingredients, order a Negroni. When you drink it, think about the simplicity of your spirits and your finances. An even better idea: Make one yourself.

The Humble Negroni

The Humble Negroni

1¼ oz. Campari

1 oz. sweet vermouth

1 oz. gin

Orange slice, for garnish

Directions: Combine the gin, sweet vermouth and Campari in an ice-filled old-fashioned glass. Thoroughly stir. Garnish with the orange slice.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.The post Stick to the Classics appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Shrink That Estate

I OUTLINED 10 REASONS everybody should have an estate plan in a 2018 article—and what was true then remains true today, especially for those whose assets could be subject to estate taxes.

Under today’s rules, the federal estate tax applies to individuals with assets over $12.9 million. That might sound like a high number. But in 2026, the limit is set to be cut in half. In addition, many states impose their own estate tax, which kicks in at much lower levels.

Because the federal estate tax stands at a hefty 40%, there’s plenty of incentive for high-net-worth families to do what they can to lessen its impact. And yet what I’ve found over the years is that, for many people, estate planning falls to the bottom of the to-do list. There’s a number of reasons for this. Chief among them, in my opinion, is the fact that estate planning requires time and mental energy. Because it’s not a routine task, it can seem like a black box, and many people don’t know how to approach it or where to begin.

Fortunately, there are easy ways to get started. Each of the following strategies can be effective in reducing future estate-tax exposure.

Annual gifting. This is the simplest and probably the best-known strategy, but it’s also underestimated. Here’s how it works: In addition to the $12.9 million lifetime exclusion referenced above, tax rules allow additional gifts to be made on an annual basis. This year, the limit for these annual gifts is $17,000. If your assets exceed $13 million, and you’re trying to defray estate taxes, that might not sound like much, but it can be highly effective.

That’s because it’s $17,000 per donor and per recipient. Consider a husband and wife who have three grown children, all married. That’s two donors and six recipients, for a total of 12 potential gifts of $17,000. That adds up to $204,000, and this could be repeated each year. If you’re able to do this for several years, the compounded value of those gifts could be significant.

Paying tuition and medical expenses. The lifetime exclusion has two notable exceptions: Parents or grandparents are permitted to pay any amount of tuition for family members—or anyone else, for that matter—as long as those payments are made directly to the educational institution. This can be an effective way to move six-figure sums out of your estate. A similar exclusion also applies to medical expenses, which also must be paid directly to the medical provider in order to qualify. While you hopefully won’t need to take advantage of the medical expense exclusion, it’s good to keep it in mind.

529 accounts. Many families establish 529 accounts to help fund their children’s education. In many cases, this makes sense. But they may not make sense for the wealthiest families. That’s because, as described above, tuition has its own exclusion, which is unlimited. Consider a set of high-net-worth grandparents with five grandchildren. They could establish 529 accounts, and that would have the benefit of moving assets out of their estate.

The alternative, though, is that they could instead pay all of their grandchildren’s tuition bills directly. If private college costs $80,000 per year, the total tuition bill for the five grandchildren would be $1.6 million ($80,000 x four years x five grandchildren). All of that could be moved out of the grandparents’ estate without any impact on their lifetime or annual exclusions. While 529 accounts do have the benefit of tax-free growth, the resulting estate-tax savings on this $1.6 million could easily outweigh the tax benefit offered by 529s. But like everything in personal finance, the right decision will depend on the particulars of your family and your finances.

Roth conversions. These aren’t normally viewed as an estate tax strategy, but they’re actually one of the easiest and most powerful strategies available. That’s because a Roth conversion triggers an immediate income tax, and that tax will be paid using dollars that otherwise would have been subject to the estate tax at death. Suppose you complete a Roth conversion of $200,000 and pay $50,000 in associated taxes. Assuming a 40% estate tax rate, this move alone would reduce your estate tax burden by $20,000 ($50,000 x 40%).

Changing your residence. Today, some states have their own estate taxes, but most don’t. If your assets top your state’s threshold, you might consider changing your residence to a no-tax state. Note that you can’t simply buy a vacation home and spend 51% of your time there. You need to change your primary residence in a meaningful way.

What else can you do? I contacted an estate-planning expert and asked for his recommendations. Amiel Weinstock is an attorney in Brookline, Massachusetts. He offered a three-part prescription.

First, recognize that estate planning means different things to different people. It isn’t one-size-fits-all, so the most important first step is to assess your own needs. Older folks, especially those with likely estate tax exposure, will want to focus on wealth transfer strategies. That’s where there’s going to be the most leverage. But for families with young children, a basic will and revocable trust may be the most important thing, because these documents will ensure that the right people are in place to care for and manage the assets of any minor children.

Second, Weinstock emphasizes the importance of term-life insurance for those in their working years. “You could have the best estate plan in the world, but you need to be sure your family would have enough to live on.” The two go hand in hand. If you don’t have sufficient insurance, start this process today. Why? “If you get sick, your insurability could change overnight. But you’d still have time to put together an estate plan.”

What if you’re older and facing likely estate tax exposure? Weinstock offers this third recommendation: Don’t view estate planning as an all-or-nothing project. If you haven’t yet taken steps to manage your estate tax exposure, consider implementing just one strategy to start. You could, for example, set up an irrevocable trust and move a handful of assets into it. Then reassess the following year.

This is good advice. In my experience, many wealthy families delay putting strategies in place because the task seems daunting. But it need not be. Bear in mind that asset values tend to rise over time. Result? The best time to get started is, in most cases, today.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Shrink That Estate appeared first on HumbleDollar.