Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 106

December 19, 2023

It’s Not So Bad

EVERY GENERATION HAS its own unique perspective—one that’s shaped by its environment, but also limited by a lack of appreciation for the past. Are things all that bad in the 2020s? I think not.

A recent Bloomberg radio discussion mentioned that, when families go out to dinner, they become keenly aware of inflation when they pay, which in turn affects their view of the economy. It took me a minute to digest that. Is going out to dinner no longer a luxury? Growing up, my family’s idea of going out to eat was 12-cent hamburgers—equivalent to just $1.36 in 2023 dollars—at White Castle on Sunday after church.

For the 12 months through November, the U.S. inflation rate was pegged at 3.1%. Is that so horrible? Inflation goes up and down. Today’s rate pales next to the 13.6% we had in 1980. While rising wages have lately been somewhat offset by inflation, inflation is coming down but today’s higher wages will continue to compound into the future.

We came out of the pandemic in pretty good shape. Net worth for the typical U.S. household grew 37%, after inflation, from 2019 to 2022, according to the Federal Reserve. Americans saved a great deal of money—$2.6 trillion—over a couple of years, although it appears most of that has now been spent. Going out to dinner too often, perhaps? I wonder how much of the complaining about the economy is the result of individual decisions, missed opportunities and tainted political rhetoric.

Yup, the price of gasoline is high, but do Americans understand the international nature of oil pricing and its impact on gas prices? Americans complaining about today’s cost of gas probably weren’t among those waiting in line for five or 10 gallons during the 1973-74 oil crisis. Back then, the price of oil quadrupled in just four months.

The U.S. has experienced financial and economic crises that were far worse than what we’ve seen of late:

The Panic of 1873 led to a sharp decline in industrial production and a rise in unemployment. Ditto for the Panic of 1907.

The Great Depression of the 1930s was the longest, most severe economic downturn in recent U.S. history. Gross domestic product, the standard measure of the nation’s economic activity, plummeted 27%. Unemployment peaked at 25% and millions of Americans were forced into poverty.

The 1980-82 recession gave us sky-high interest rates, a decline in consumer spending, a slowdown in economic growth and a jump in unemployment.

The 2008-09 Great Recession saw a collapse in the housing market, a deep stock market selloff, and a banking crisis that required an all-out emergency response by the U.S. government.

Mortgage interest rates are high now, you say? The average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is 6.95%. When I bought my first house in 1971, the rate was 7.5%. On two other home purchases, in 1975 and 1987, we had rates of 9.5% and 9.75%, with 20% down payments required. In 1981, the 30-year mortgage rate touched 16.6%.

Today, it’s still possible to buy a house with a 3.5% down payment using a Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loan. Elsewhere, a 5% to 10% down payment is common.

Although it may not feel like it, with endless crises here and there, things have been rather peaceful lately compared to the past century. Young Americans no longer worry about a military draft disrupting their lives.

Think of the impact on Americans of World War I, World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam. Sixteen million Americans served in World War II. Today, the entire active-duty military is about 1.3 million volunteers.

We worry about the price of dining out. I wonder if Americans today would accept using a ration book to buy sugar, meat, canned goods and tires, as they had to during World War II?

The “tough times” are even blamed for not having children. For millennials, the Great Recession, soaring student debt, precarious gig employment, skyrocketing home prices and the COVID-19 crisis are apparently all reasons not to have children, according to an article in The Washington Post. I guess I’m lucky. I was born in the middle of World War II. That could have been a whopper of an excuse.

Don’t get me started on student debt. Having earned Veterans Affairs tuition benefits by serving in the Army, and later paying for our four children's college, I know a college education is a good investment—but I also know it’s one that needs to be paid for.

How are things at work? “They stink,” I was recently told by a worker at my old employer. I have no doubt the workplace is different than it was in my day. Any semblance of corporate paternalism is gone. The link between employment and long-term financial security is tenuous. In reality, that link only ever applied to large employers, and not to the small businesses where the majority of Americans work.

Even as job security has weakened, many Americans have adopted a different view of work. Younger generations seek a better work-life balance while also wanting early retirement. Today, 12.7% of employees work from home fulltime, and another 28.2% work from home sometimes, and their ranks are growing. If I had asked my boss to work from home—preferably on Fridays and Mondays—he would have laughed, or worse.

As with other aspects of our lives, the workplace was far worse in times past. You don’t have to go back to the days of steel barons Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick to find intolerable workplaces. When I began work, the unspoken road to the top was being white and Protestant. Women were second-class citizens and minorities were openly avoided.

While every generation has its challenges, 2023 doesn’t strike me as all that bad.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.net. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. Follow him on X (Twitter) @QuinnsComments and check out his earlier articles.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.net. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. Follow him on X (Twitter) @QuinnsComments and check out his earlier articles.

The post It’s Not So Bad appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 18, 2023

Winning Ticket

STOCK INVESTORS TALK about taking advantage of market inefficiencies. That sounds nice, but I don’t have any confidence I can spot mispriced stocks, which is why I stick with mutual funds, especially index funds.

But there’s a market inefficiency where I’ve done pretty well—train tickets. In my late 60s, when I was in my final job, I commuted from central New Jersey to Philadelphia by train. This meant parking my car at the station, taking New Jersey Transit (NJT) two stops, and then switching to the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) train into Philadelphia.

Door to door, this took two hours. For those readers who walk to work or drive 15 minutes, this might sound like a lot. But in the New York area, two-hour commutes are fairly common.

I had the option of either buying a monthly ticket or purchasing single-ride tickets. A monthly ticket is convenient. All you need is the one piece of paper for as many trips as you take within that month. As a senior—defined as age 65 or older—I was entitled to a fare discount. This discount applied to both monthly and single-ride tickets.

SEPTA is especially generous to seniors. You could travel anywhere within the SEPTA system for free—as long as you stay in Pennsylvania. But if you travel on SEPTA to Delaware or New Jersey, you have to pay. I only traveled one stop into New Jersey but, because of this, I needed to buy a ticket. I didn’t like this.

Meanwhile, I also discovered that NJT conductors weren’t that efficient. Sometimes, they decided—for reasons unknown to me—not to collect tickets. Had I bought a monthly ticket, this wouldn’t matter, since I’d have paid for the whole month, whether I took the train or not.

The upshot: I decided to buy individual tickets at the senior discount—and tried to take advantage of “train market” inefficiencies.

When I got on the train, I’d always have NJT and SEPTA tickets. If the conductor asked for my ticket, I’d hand it over. If the conductor didn’t, I’d keep the ticket for my next trip.

Riding the train every day, you tend to see the same conductors. Once they recognized me and they knew I didn’t have a monthly pass, they’d always ask for my ticket, which I would give them. There were no inefficiencies in this case. But when there was a new conductor working, I often got to keep my ticket.

This situation played out best on SEPTA coming out of Philadelphia at the end of the day. When new conductors worked the train, they didn’t know where I was going, nor would they ask. I’d show my SEPTA senior ID and get a free ride.

For those readers who feel I cheated these transit companies out of revenue, keep in mind that I always bought tickets and never got on the train without one. I simply used them as required. No, I didn’t go out of my way to give my ticket to the train conductor. But I would have done so—if the conductors were doing their job.

An added twist: To pay for both parking and train tickets, I would fund a pretax flexible spending account through my employer. But I needed to spend the full monthly amount or it would be lost. And sometimes there was indeed money left over.

What to do? The leftover money could only be used to buy train tickets, which meant buying yet more SEPTA or NJT tickets.

NJT senior tickets can be used by riders age 65 and over and by the disabled. My wife, son and I all fall into these categories, so I used the extra dollars to buy NJT tickets. We’d then use the tickets to travel into New York City or go to Newark airport. And there was no rush to use the tickets—because they don’t have an expiration date.

The post Winning Ticket appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Getting Rolled

THE SECURITIES AND Exchange Commission recently proposed that registered financial advisors be compelled to act as fiduciaries when recommending rolling over 401(k) money to an IRA. Whether this rule gets adopted or not, plenty of advisors are eager to help investors with the issue.

Indeed, as I approached retirement, a number of advisors contacted me about rolling over my 401(k). Of course, these advisors also offered to manage my funds for a fee, usually around 1% a year of assets. I joined colleagues at a few lunchtime seminars that were put on by advisors who worked mainly with retirees from our employer. A couple of my friends ended up hiring one of these folks.

These advisors were, I believe, offering sound advice. Some colleagues had no interest in building a portfolio on their own, let alone understanding the complexities of when to claim Social Security or how to manage their income to reduce the Medicare premium surcharge known as IRMAA.

My quibble was with the amount the advisors were charging for their services. Let’s assume an engineer had been contributing to a 401(k) for 40 years, and the company had been matching part of those contributions. It wasn’t unheard of for the engineer to have a $1 million 401(k).

Although there were expenses associated with the 401(k), our company had chosen the plan provider carefully and the costs were minimal. By contrast, an advisor charging 1% of assets per year would be pocketing $10,000 annually from a $1 million IRA.

Let’s assume advisors were charging $500 an hour for their time. That would imply that they should be spending about 20 hours a year to develop a financial plan for you. In your first year as a client, as they get to know you and your goals, 20 hours seems like a reasonable estimate of the time they might spend on your account.

My concern was the second year: Was it really going to take another 20 hours that year, and every year thereafter? Although the advisors we spoke with were suggesting rolling the 401(k) into a series of low-cost exchange-traded funds, there’s a risk some advisors might recommend ETFs with higher fees than we were paying in our 401(k).

What did I do? Did I keep my money in the company 401(k)? Did I hire an advisor? My decision was based on a desire to simplify our finances as much as possible for my wife, should I die before her. I rolled the 401(k) over to an IRA at the brokerage firm we use for our taxable account investments, and then built my own portfolio.

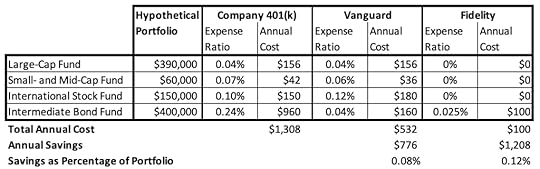

The table below shows the cost of a hypothetical $1 million account at both Vanguard Group and Fidelity Investments, compared with my old employer’s 401(k). While Vanguard and Fidelity don’t offer funds tracking the exact same indexes as the 401(k) provider, you can get pretty close by choosing similar categories. As you can see, by carefully selecting low-cost funds, it was possible to keep costs comparable when moving to an IRA—and there was an opportunity to cut expenses.

Once I completed the rollover, I spent a few hours planning conversions of my IRA money to Roth IRAs, so I’d minimize future Medicare premium surcharges. All in all, I believe I’ve captured 90% or more of the benefit that an advisor might provide, and for a far lower cost than 1% of assets.

The post Getting Rolled appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 17, 2023

Taste Those Savings

I GET A THRILL FROM saving money on groceries. We have customer loyalty cards for the two local grocery stores where we do most of our shopping. The sales receipts list total savings for that shopping trip. I love to see big numbers on that line.

I’m a prodigious cereal eater, and my favorite is Cheerios. The regular price for the smallest box is $4.99. Of course, I never pay that. Fairly frequently, one of the local stores runs specials on General Mills brands, and the price for small boxes of Cheerios is often two for $6. Occasionally, they’re two for $5 or even two for $4. I have on rare occasions even purchased two for $3. At $1.50 a box, that’s a savings of 70% over the regular price.

If a cereal I eat regularly is discounted significantly, I’m likely to buy it even if we have some in stock already. I’ve also sampled the various store brands of cereal, which are priced much more favorably. I’ve found that I like some as much as the name brands, while others I’d never buy again. None of the generic substitutes for Cheerios tastes good to me. On the other hand, I can’t tell the difference between generic and name-brand frosted mini-wheats.

What about other grocery store items? I generally don’t buy things like pouches of tuna, pasta sauce, certain frozen dinners and name-brand orange juice unless they’re discounted. Similarly, I usually won’t try out a new product unless it’s offered on sale.

I have an online account for one of our local stores where I can redeem points accrued on past purchases to get a discount on a future bill. Each month, I typically get a $3 or $4 reward for my efforts. Hey, every little bit helps.

I’m not a coupon clipper, but I recently downloaded a grocery store’s app to my phone, and I’ve used it a few times to get some good deals. This is a potential growth area for me. With the help of digital coupons on a recent trip, I saved $14.38 on a $50.57 bill. That’s a savings of more than 28%.

On one of my many spreadsheets, I keep track of our spending on groceries and related items. I track total spending by store, not by individual purchase. For example, everything we spend at Costco goes into the tally, even though we occasionally purchase non-food items there. Despite all the concern about food inflation, my spreadsheet indicates these expenses have remained steady over the past few years.

My efforts as the family’s secondary grocery shopper result in admittedly small overall savings, but it gives me some sense of control in the face of spiraling price increases. I have to give my wife Lisa credit for becoming an increasingly discriminating shopper. Funny thing is, she’s managed to do this without even bothering with spreadsheets. Go figure.

Now that I’m semi-retired, I can accompany Lisa to Costco more frequently. The last time I went, we purchased two extra-large boxes of Cheerios for $3.99. That’s the equivalent of less than 87 cents for a small box, a discount of more than 80% over the regular price. That’s far better than the best price I’ve ever gotten at a grocery store. I may need to update my strategy.

The post Taste Those Savings appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Time for a Checkup

AS WE HEAD INTO year-end, many are cheering the financial markets’ returns. The S&P 500 has gained nearly 25% and now sits just a hair below its all-time high. Bonds are also looking more attractive, with yields at 15-year highs.

As a result, many investors are feeling a whole lot better about their portfolio balances. That’s certainly one way to measure financial progress, and it’s an important one. But as you make plans for 2024, there are other financial metrics that also deserve your attention.

Simplicity. A few years back, MIT professor Andrew Lo co-authored a book titled In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio. The punchline of the book: There’s no such thing as the perfect portfolio. Instead, the message is that there are many ways to structure a successful investment plan.

What would an ideal portfolio look like to me? It would be so simple it would fit on an index card. It would have just a limited number of holdings—mostly index funds. And it would be so straightforward that you wouldn’t need a spreadsheet or sophisticated analysis to understand it. You could calculate the asset allocation in your head. A simple set of investments makes a portfolio easier to monitor and to manage. And often, it carries two valuable “efficiency” benefits, described below.

Tax efficiency. Last year, I described an investor I called Jane who had a curious experience with a mutual fund. Back in the 1990s, Jane had purchased shares in the fund for $19,000 and, a few years ago, sold her holdings for nearly $300,000. It looked like a significant gain, and she expected a large tax bill. But it turned out Jane was able to report a loss on her tax return. Why? The fund had been issuing sizable taxable distributions nearly every year. As those distributions were reinvested at higher and higher prices, they increased Jane’s cost basis. That allowed her to claim a loss when she sold.

What was wrong with this picture—and a key reason I recommend steering clear of actively managed funds—is that Jane had no control over the income that this fund was generating throughout her working years, when she was in a high tax bracket. By contrast, index funds and exchange-traded funds issue far fewer—if any—taxable distributions.

Early next year, when you review your 1099 tax forms, look for funds like the one Jane owned. If you see any, I suggest looking for ways to reduce those holdings. If there isn’t much of a gain, you could simply sell them. Alternatively, if there’s a significant gain, consider donating them to a donor-advised fund.

Cost efficiency. Another key benefit of simple funds: They tend to have modest expenses. According to the research, controlling investment expenses is a key lever in controlling your returns.

Here’s how the research firm Morningstar once described the importance of fund fees: “If there’s anything in the whole world of mutual funds that you can take to the bank, it’s that expense ratios help you make a better decision. In every single time period and data point tested, low-cost funds beat high-cost funds.” Fortunately, there tends to be a lot of overlap between funds that carry high fees and funds that are tax-inefficient, making it easier to identify candidates for removal from your portfolio.

Saving. If you’re in your working years, savings are another key metric. You could look at your overall savings rate, and that’s certainly important. But also check whether you’re saving in the right types of accounts. Just as you want to adjust your asset allocation as your financial situation changes, you want to be sure the savings vehicles you’re using still align with your current tax status.

What types of accounts should you consider? In addition to the most commonly used accounts, such as 529 plans, 401(k)s, 403(b)s and Roth IRAs, investigate some of the lesser-known options. If you have a very high income, see if your employer offers a deferred compensation plan. If you’re self-employed, a solo 401(k) can be a good choice. And if you’re self-employed, have a very high income and are further along in your career, you might look at a cash balance plan.

Sustainability. If you’re in retirement, probably the most important metric is the sustainability of your retirement-income plan. After a strong year in the markets, this is likely less of a concern than it was a year ago, but it’s worth confirming. There's a number of approaches, including the “4% rule,” the “guardrails” method and Monte Carlo analysis. Each has some value, so I suggest looking at your plan through more than one lens. What’s most important is simply to check on your plan regularly.

Cash flow. Whether you’re in your working years or in retirement, a key objective should be to simplify your cash flow so you can spend less time tending to mundane financial tasks—or, worse yet, worrying about them. As we enter the new year, look for ways to streamline.

Try, for example, to cut down on the number of credit cards you use. Or, if you want to use multiple cards, ask the credit card companies to set all the payment due dates to the same day of the month, making it easier to stay on top of payments. The metric in question here isn’t your cash flow per se. Rather, it’s the simplicity of managing that cash flow.

Disaster-proofing (Part I). Author William Bernstein uses the term “deep risk” to talk about the most extreme investment risks. These include hyperinflation, deflation, government confiscation and devastation (such as war). Bernstein acknowledges that there’s no silver bullet for guarding against these kinds of risks.

Fortunately, there’s another type of risk—what Bernstein calls “shallow risk”—that’s much easier to manage. Shallow risk refers to the ordinary ups and downs of the market, and effective asset allocation can go a long way toward inoculating your portfolio from this risk. As we head into the new year, it’s important to confirm that your chosen asset allocation still aligns with your needs.

Disaster-proofing (Part II). Earlier this year, I told the story of two friends who had both had their bank accounts compromised. While hacking is an unfortunate reality, there are steps you can take to secure your accounts. In September, I offered a number of suggestions. Most important: Try to secure as many of your accounts as you can with two-factor authentication, especially the type that doesn’t rely on text messages, which can be an Achilles’ heel.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X (Twitter) @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X (Twitter) @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Time for a Checkup appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 15, 2023

Happily Ever After

INVESTING IS ABOUT finding a strategy that’ll allow us to meet our life’s goals—and which we can live with along the way. That brings me to a major portfolio change I made two years ago, and a series of changes I’m planning for the years ahead.

In late 2021, I split my portfolio in two. One part I’ll use to fund my retirement, while the other part I’ll leave to my two kids. This “bequest” portion consists of my three Roth accounts, which are roughly a quarter of my overall portfolio. Because I don’t foresee ever touching this money, I’ve invested the entire sum in stocks.

I settled on a single fund, Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund, which is available as both an exchange traded fund (symbol: VT) and a mutual fund (VTWAX). I view it as the ultimate in stock market diversification, owning all of the world’s publicly traded companies of any significance, with 61% currently in U.S. stocks and 39% invested abroad.

In the two years since, financial markets first nosedived and then recovered. There’s been all kinds of horrific mayhem, not least in Ukraine and Israel. Concerns have been raised about the return of inflation, the sustainability of U.S. government spending, the impact of rising interest rates on stock market valuations, and the prudence of investing in authoritarian China.

And yet, through all this, I’ve given scant thought to my Vanguard Total World holdings. At this point in my life, that’s exactly what I want. I have no clue which parts of the global stock market will shine in the years ahead, so I’m happy to own the whole shebang, confident that—while companies and even entire markets will fall by the wayside—the global economy will keep chugging along, and Vanguard Total World will go along for the ride.

Looking up. What about my portfolio’s other three-quarters—the money that’s not part of my “bequest” Roth accounts? Today, I own index funds focused on the total U.S. stock market, total international stock market, U.S. large-cap and small-cap value stocks, international value stocks, emerging markets and foreign small-cap stocks, plus a couple of short-term bond funds focused on conventional and inflation-indexed government bonds.

I've owned these funds for years and I believe all are worthy long-term investments. But after two pleasurable years of ignoring my Vanguard Total World holdings, I’m just not sure I want to be bothered anymore with most of these other funds.

I’m not claiming Vanguard Total World is the right stock fund for everybody. It’s marginally more costly than owning the world through two separate total market funds, one targeting U.S. stocks and the other owning foreign shares. Vanguard Total World also isn’t the best holding for a taxable account, because right now holders won’t qualify for the foreign tax credit. And its basic investment mix will strike many folks as uncomfortably risky, thanks to its 39% allocation to foreign shares.

But the way I see it, the fund is the least risky stock fund you can own. It isn’t overweighting anything, but rather simply holding the world’s stocks according to their importance, as measured by market value. Whatever happens in the years ahead, the fund will continue to do just that, with no need for me to rebalance or make any other tweaks. That’s why I’ve decided that Vanguard Total World should be my sole stock market holding, not just for my “bequest” accounts, but also for the “pay for retirement” portion of my portfolio.

Looking down. That still leaves the small issue of actually paying for retirement. I’m about to turn age 61, and I still earn enough to cover the bills, so I’m not yet dependent on my portfolio for spending money. But in the next few years, that day will come—and I’ll need spending money that isn’t subject to the vagaries of the stock market.

In recent years, as I’ve looked ahead to my eventual retirement, my target for the “pay for retirement” portion of my portfolio has been 80% stocks and 20% short-term bonds. My thinking: If I was withdrawing 4% of savings per year and I wanted enough set aside to ride out five rough years in the stock market, I’d need five times that 4% in bonds, or 20%.

To be sure, once I’m fully retired, it could be that 20% strikes me as an uncomfortably thin safety net, and perhaps I’ll want, say, seven years of spending money, or 28%, in short-term bonds. The fact is, it’s hard to know exactly how I’ll feel about investment risk once I no longer have any earned income.

On the other hand, I may decide to keep even less in bonds—for two reasons. First, when I claim Social Security at age 70, my benefit is currently slated to be $55,000 a year, figured in today’s dollars. I feel like I live pretty well, traveling and eating out often. But maybe I need to step up my game—because that $55,000 will cover the bulk of my spending.

Second, to cover the gap between what Social Security will pay me at age 70 and what I spend, I plan to make a series of immediate-fixed annuity purchases from different insurers that’ll pay me lifetime income. The upshot: Once I make those annuity purchases and once I claim Social Security, I may need zero dollars from my portfolio each year for spending, and hence I could potentially keep far less than 20% in bonds.

This brings me to a point I’ve made before, but it bears repeating. Others view delaying Social Security and buying immediate annuities as somehow cheating their heirs. I’d argue just the opposite is true. As long as I live into my 80s, my strategy will potentially mean more wealth for my heirs—because it’ll allow me to allocate far more of my portfolio to stocks, while also drawing little or nothing from savings from age 70 on.

Yes, I'll need to start taking required minimum distributions from my IRA. But there's no law that says I have to spend that money. I'll likely use part for qualified charitable distributions and part for gifts to my kids, while reinvesting the rest in my regular taxable account.

Getting there. That brings me to a second small issue: putting my plan into action. As a first step, I need to swap out of my current index-fund holdings in my “pay for retirement” portfolio and into Vanguard Total World.

Problem is, that means abandoning my portfolio’s overweighted positions in value stocks, smaller companies and emerging markets. These holdings fared well in the current century’s first decade, but not so well over the past dozen years—and that gives me pause. While I claim no crystal ball, I’m also loath to give up on these overweights at what feels like a bad time in the market cycle, so I plan to make the shift slowly over perhaps a handful of years. And, no, this isn’t a tax issue: Almost all of these funds are held in a retirement account, so moving money around won’t trigger any tax bill.

What about buying the lifetime income annuities? Folks have suggested that I should buy now, while interest rates are relatively high. But my inclination is to wait until I have a firmer retirement date. Interest rates may indeed fall in the meantime, but delaying also means sellers of immediate annuities will pay me more because I'm closer to death. That's the dubious privilege that comes with getting older, and I figure I might as well take advantage.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X (Twitter) @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X (Twitter) @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post Happily Ever After appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Settling Down

THESE WORDS STRIKE fear into the heart of any husband: “Honey, the [insert: A/C, heat, refrigerator, roof, foundation] doesn't seem to be working.” But from 2017 to 2021, they were mere words to me, no different than, “Honey, let’s go out for coffee.”

For four glorious years, my wife and I traveled around the world and the country, unfettered and unburdened. If we ran into any equipment issues, they were immediately referred to the landlord for rectification. Even if they couldn’t be immediately resolved, they were now someone else’s responsibility to correct and, more important, to worry about.

In 2022, soon after purchasing a new home, my wife uttered, “Honey the A/C doesn’t seem to be working,” as I dozed while reading—if I remember correctly—Security Analysis. I joked that she should inform the landlord, but when she replied, “I just did,” the worrying began.

I don’t mind the small stuff, such as minor plumbing issues. In fact, they can bring a fair amount of satisfaction. It’s the big stuff that has taken some getting used to. Like the A/C not working. Here are the top five issues we’ve encountered since we settled down:

1. Owning a car may be the birthright of every American. It offers the freedom to travel, but also the tyranny of ownership. Most of our worldwide travel was accomplished sans auto and, therefore, sans worrying about tire rotation, the check blood pressure light or finding parking. We now have a garage, and a car sits in it. I’d rather not have the worry. But then again, I’m proud to be an American.

2. Where we live, property taxes are reassessed every two years, and I’m anxiously awaiting my new assessment. I’m hopeful it’ll be more than fair. But fair or not, I have no idea how our home’s value is determined. If you do your own income taxes, you have a good idea how they were calculated, but not so with property taxes. If I don’t like it, I guess I need to file a dispute, right? As my mother used to intone, “Please say a prayer.”

And don’t get me started on state income taxes. While they’re slightly less inscrutable than property taxes, they operate on a different paradigm than federal taxes and therefore have a less comforting way of handling my dividends. During my travels, I was a proud citizen of the great state of Texas. But now I’m a citizen of another state—one that, unfortunately, has an income tax.

3. After a year abroad, we spent the next three interviewing cities for residence. We finally settled down in a city we’d never lived before. Which besides requiring the acquisition of a new residence, required the acquisition of new friends.

Well, past a certain age, which is less than my current age, this is easier said than done. After moving in, I thought I made one, but soon after was informed, “Guess what? My house is for sale. I’m moving.”

While we have made a couple of good friends subsequently, it’s been an uphill struggle. We live in a condo filled with much younger residents and I think there may be an element of ageism. Then again, it may be an element of me.

4. When we unpacked the POD that contained all our earthly possessions—after wondering why we packed so much of this “gold” in the first place—my wife said to me, “Let’s keep it all in the garage and only unpack the stuff we really need.” I heartily agreed with her. I imagined myself as Robert De Niro in the movie Heat , a professional thief living in an empty house, so he could clear out at the drop of a hat and stay one step ahead of the law.

Needless to say, the house is now filled with all the stuff from the garage, as well as some additional stuff. While some stuff is necessary for living, sometimes I fondly remember what it was like to be on the run.

5. A few months after moving in, I was lying on our new couch, either watching CNBC or Chicago Fire, when I noticed water was dripping from the ceiling A/C vent. It turns out the drain on the patio above was leaking, but due to my hawk-like vision, damage to our recently unpacked Noguchi-inspired coffee table was avoided.

It took too many months to affect a permanent repair. During that time and after, I didn’t worry when it rained, as I could keep an eye on everything. But when we were traveling and it rained, it was all I could think about. It made me realize there’s only one thing better than travel, and that’s travel without having to worry about the car, property taxes, making friends and coffee tables.

Having a new home has brought some changes, some worry and, I hope, some new friends. As I type this, I’m drinking a Molson Canadian Lager, as there’s no better way to enjoy the sunset while overlooking the Toronto skyline. Still, if you have a chance, could you swing by our house and make sure everything is okay?

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.The post Settling Down appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 14, 2023

Becoming an Investor

MY DREAM WAS TO become a brilliant investor who knew when and what to buy and sell. I imagined myself doing the necessary research, which would allow me to make savvy decisions, which would then impress my wife and relatives, as they observed my uncanny ability to always know what to do and when to do it.

This never happened.

Instead, I took stock of who I was and how I’d consistently behaved. “Know thyself” was the advice of Ken Pangburn, CEO of a company I once worked for. That’s what I endeavored to do. What I realized: I’m a saver, someone who has no difficulty skipping a purchase and instead putting the money in the bank.

Now, this is a good start. But it’ll never get you onto the Forbes 400 list of America’s wealthiest. I needed to step on the accelerator a little.

I undertook an in-depth study of investing. I had a good grasp of savings accounts and certificates of deposit. What I needed to learn was the other stuff. Stocks were the biggest mystery. I understood that owning shares meant you’re an owner of the company. But which stocks should I buy?

This led to studying fundamental vs. technical analysis, and thinking about whether to be a value or growth investor. Should I own individual stocks or mutual funds? If I buy mutual funds, should they be actively or passively managed? It was all very confusing.

I felt I had a better handle on bonds because I’d owned some savings bonds. Still, the same questions I had about stocks also applied to bonds. Do I buy individual bonds or mutual funds? Should I buy government or corporate bonds? Still very confusing.

This confusion took me back to who I fundamentally was. I was a saver. Period. Full stop.

How does a saver become an investor? I was first introduced to Vanguard Group through my company's 401(k) plan. Vanguard has a one-stop-shopping option in the Wellington Fund, a balanced fund. Such funds typically have roughly 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, so 60-40 became my default asset allocation, which I have continued to use to this day. Simple.

The next question was tax-deferred or taxable-account investing. Both had their merits, so I did both. After watching Suze Orman’s show one night, I learned I could fund a Roth IRA, even though I was contributing to my company’s 401(k). I continued doing so until I stopped working. I didn’t, however, choose to convert any IRA dollars to Roth dollars. That would have reduced my future required minimum distributions, but I didn't want to pay the taxes until I had to.

Another question that I needed to answer: active or passive? One of the tenets of investing is diversification. Why not diversify by management style? So, I did both. This diversification approach continued with the size of companies owned by my stock funds and the country of my investments.

The next strategy I adopted was dollar-cost averaging, since it struck me as similar to putting money into a Christmas club savings account. As long as I didn’t put too much money into any one investment vehicle, I could sleep at night.

The final decision I needed to make: Do I rebalance back to my 60-40 mix? I decided to do it once a year. I do this in my IRA, not my regular taxable account. In my taxable account, I simply put more dollars into whichever asset class is underweighted, trying to gently nudge the account back into line. Meanwhile, I don’t need to rebalance in my Roth, because in that account I own a balanced fund that does the job for me.

David Gartland was born and raised on Long Island, New York, and has lived in central New Jersey since 1987. He earned a bachelor’s degree in math from the State University of New York at Cortland and holds various professional insurance designations. Dave’s property and casualty insurance career with different companies lasted 42 years. He’s been married 36 years, and has a son with special needs. Dave has identified three areas of interest that he focuses on to enjoy retirement: exploring, learning and accomplishing. Pursuing any one of these leads to contentment. Check out Dave's earlier articles.

David Gartland was born and raised on Long Island, New York, and has lived in central New Jersey since 1987. He earned a bachelor’s degree in math from the State University of New York at Cortland and holds various professional insurance designations. Dave’s property and casualty insurance career with different companies lasted 42 years. He’s been married 36 years, and has a son with special needs. Dave has identified three areas of interest that he focuses on to enjoy retirement: exploring, learning and accomplishing. Pursuing any one of these leads to contentment. Check out Dave's earlier articles.The post Becoming an Investor appeared first on HumbleDollar.

My Four Favorites

I'M A BELIEVER. SURE, I stray every now and then. But after a late start, I’ve now been a devotee of exchange-traded funds for many years—though some of the ETFs I own would be considered actively managed.

In his iconic A Random Walk Down Wall Street, Burton Malkiel strongly advocates long-term passive investing as the strategy of choice for individual investors. But he also confesses to having been “smitten with the gambling urge since birth.” Acknowledging that index fund investing can be “boring,” he takes pity on folks like me with “speculative temperaments,” who may need to indulge those instincts with some small portion of their portfolio.

Thus absolved for intermittently falling off the wagon, I thought it might be of interest to readers—and useful for me—to sketch out how I’ve invested the bulk of my taxable account. (I plan to write about our household's retirement accounts in a separate article.) I’m a big believer in diversification, perhaps the only free lunch on Wall Street.

By that, I mean I pay careful attention to my portfolio’s stock-bond allocation, mix of U.S. and foreign stocks, balance of growth and value, size of companies owned and even sector tilts. I’m a semi-retiree who needs cash to compensate for his overinvestment in illiquid real estate, while also hoping to increase my net worth for my heirs.

Toward those two ends, I’ve put together a moderate growth portfolio. It throws off a healthy 6% yield and is structured to participate in about two-thirds of the stock market’s move, whether those moves are up or down. Yes, I shortchange myself in bull markets. But a stubborn anxiety dictates that my ship be seaworthy during the inevitable storms, or there’s a danger I may bail.

So, what’s this longwinded guy own? Because each is so diversified, I’m happy to own just four main ETFs in my taxable account. One fund is almost half of my portfolio, and the other three are held in roughly equal amounts. By the lottery of birth and parents, I am constitutionally ill-suited for high-octane investing and thus deliberately underweight technology.

I consider JPMorgan Equity Premium Income ETF (symbol: JEPI) my core holding. It’s a covered call fund that combines the income from selling call options with dividends from high-quality companies, and it currently yields almost 9%. But it comes with three significant caveats.

First, it isn’t designed to generate capital gains, but it’s still sensitive to market declines. The ETF has a slight technology overweight, but the options-writing strategy gives me a relatively safe way to venture into that forbidden territory. Second, the options strategy means this "buy-write" ETF counts as actively managed, with a relatively high but bearable expense ratio of 0.35%. Third, all the income it generates means the fund is tax-inefficient—but that doesn’t bother me, because I need that income for living expenses.

Meanwhile, among my three other taxable-account funds, Vanguard International High Dividend Yield ETF (VYMI) gives me a substantial non-U.S. presence. It’s widely diversified across countries and benefits from Vanguard Group’s trademark low costs. Because foreign companies tend to pay higher dividends than U.S. firms, the ETF’s distribution rate is around 4.5%.

Okay, we’re moving on to my technology neurosis, so you can now start to guffaw. I have approximately 15% of my taxable account in iShares Global Tech ETF (IXN), which provides most of my portfolio’s growth-stock component, as well as supplemental international representation. The iShares offering has a relatively high expense ratio for an index fund and its dividend is nominal.

Until recently, Vanguard S&P Small-Cap 600 Value ETF (VIOV) was one of my positions. After holding it for many years, I gradually became disillusioned with its performance. As of November, its year-to-date return trails its Morningstar category average by four percentage points, putting it in the group’s bottom 16%. Its three-year record misses by two points a year and ranks in the bottom 28%. This is unacceptably poor performance for what’s presumably an index-hugging ETF.

I have therefore replaced Vanguard’s ETF with Avantis U.S. Small Cap Value ETF (AVUV). It’s another one of those reprehensible active ETFs, but it charges only 0.25%, unusually low for such a fund. To boot, this year it’s in the top 20% of its peers. Over the past three years, the Avantis fund’s 17% average annual return puts it in the top 6% of similar funds. Of course, a few years does not establish the durability of any outperformance, but the comparative loss in last year’s turbulent market was six percentage points less than its Vanguard counterpart.

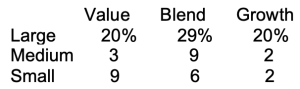

When I was growing up, I was told only three things really matter in life: your health, your family and your friends. My parents were right as far as they went. But as a fourth item, I’d tack on Morningstar’s portfolio management tools, especially its Portfolio X-Ray  analysis. In the accompanying chart, you can see how the holdings of my four ETFs are distributed across the Morningstar style boxes.

analysis. In the accompanying chart, you can see how the holdings of my four ETFs are distributed across the Morningstar style boxes.

To be honest, I hadn’t peeked at my size and style allocation for quite a while, and I feel pleased. The large-cap allocation could not be more balanced and I have my intended overall value tilt. I appear to be underinvested in small-caps. But in my head, I combine them with mid-caps because they tend to move in tandem.

Dig deeper into the numbers and I see my desired underrepresentation in the technology sector, with me at 20% versus the S&P 500 at 28%. My average annual expense ratio is 0.31%, a little higher than optimal but for my purposes still acceptable. According to Morningstar’s Portfolio X-Ray, I have one-third international exposure. Over the past year, I’ve captured about two-thirds of the global market’s performance, which is my goal for up markets. That’s nothing to brag about, but also no reason to despair.

I take some solace in having done acceptably well, despite a light exposure to the tech sector that’s lately propelled the market’s advance. In addition, a small cash position undoubtedly detracted from my performance.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

The post My Four Favorites appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 13, 2023

House Keeping

I'M THE OWNER OF one-sixth of a house in Sarasota County, Florida. There was no cost to me to acquire it. I also don’t have to make payments for property taxes, maintenance, the mortgage or the homeowners’ association. And, no, I haven’t had a change of heart about investing in rental real estate and, no, the property isn’t part of some passive micro-investment syndication scheme.

Rather, my mother signed a life estate deed, also known as a quitclaim deed, which means her beneficiaries will eventually receive her home without going through the court-supervised transfer of estate property known as probate.

My father passed away in 2013. My mother, now age 88, began exhibiting early stage dementia five years later. At that time, we met with an eldercare lawyer to review her estate plan. We updated her will, assigned power of attorney to her oldest child and formalized her “do not resuscitate-do not intubate” wishes.

The lawyer also suggested we take steps to shield the passing of her primary residence to her children from review by the probate court. The deed for her home now has an accompanying attachment, commonly referred to as a retained life estate deed. My mother retains full control over the house, including the right to live within, sell, lease and mortgage her home.

But thanks to the life estate deed, there are now multiple parties assigned to the property deed. The legal document involved is akin to what’s sometimes known as a Lady Bird deed, named after President Lyndon Johnson’s action to transfer property without probate to his wife, Lady Bird Johnson, upon his death.

Our deed divides my mother’s ownership of the house. She retains 50% possession and full control. The remaining 50% is divided equally among her three children. Thus, I was assigned a 16.7% stake in a lovely, three-bedroom ranch-style home in a relatively high-cost-of-living gated community.

In practice, there were few changes. The Sarasota County comptroller now lists my siblings and me on the property’s deed as title holders, alongside my mother, who is termed the “grantor.” The county’s property appraiser, as well as the tax collector’s office, also have our names listed as individuals of record. This means, I assume, that we’re now all responsible for taxes and assessments if my mother fails to pay them.

In essence, my mother was able to give her primary residence to her beneficiaries during her lifetime, while retaining full use and control over the property. There are additional benefits to her surviving beneficiaries, who are heartlessly referred to in the legal document as “remaindermen.” The property is typically given a step-up in cost basis for tax purposes to match its current market value at the time of the main tenant’s death. The deed paperwork also eliminates the requirement to list specific names to inherit the property within the grantor’s will. In addition, a quitclaim deed may be useful for those hoping to have Medicaid pay for their long-term care, but that wasn't part of our motivation.

Importantly, the value of the property is not subject to gift taxes—or, at least, not currently in Florida. Be sure to check the rules in your state. Five states currently allow a Lady Bird deed: Florida, Texas, Michigan, Vermont and West Virginia.

The changes affected only how ownership is represented in paperwork. The outstanding mortgage paperwork didn’t change. Insurance, homeowner fees, power providers, internet and garbage collection service remain solely listed under my mother’s name.

While this is not a particularly difficult legal undertaking, it’s certainly not for the faint of heart. As mentioned, all parties now bear responsibility for legal issues regarding the residence. This includes all taxes and liens against the property. Also, the deed itself is difficult to reverse if, for example, a grantor later wants to disinherit a particular child. In addition, the original owner or owners may open themselves up to debt collections against a well-to-do remainderman.

I found the major hurdle was that it forced us siblings to confront our mother’s mortality. When it comes to health issues, my siblings and I resemble the three bears. One always thinks the porridge is too hot, one too cold and one just right. One sibling was able to look death in the eye, one adopted a head-in-the-sand attitude and one was practical about the matter. I could leave readers to decide which of the three bears I resembled. But the truth is, I oscillated between all three points of view.

There’s a need for strong family trust to take advantage of this transfer of generational wealth. Overall, the life estate deed was a good option for our tightly knit clan, since we’ve always been open and trusting of each other, and somewhat knowledgeable about our parents' finances and final wishes. Your mileage may vary.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. Check out his earlier articles.

Jeffrey K. Actor, PhD, was a professor at a major medical school in Houston for more than 25 years, serving as an academic researcher with interests in how immune responses function to fight pathogenic diseases. Jeff’s retirement goals are to write short science fiction stories, volunteer in the community and spend time in his garden. Check out his earlier articles.

The post House Keeping appeared first on HumbleDollar.