Jason Micheli's Blog, page 39

June 24, 2024

How to Read the Good Book Well

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Become a paid subscriber. Much love to those who do!

The lectionary Gospel passage for this coming Sunday is Mark 5:21-43:

When Jesus had crossed again in the boat to the other side, a great crowd gathered around him; and he was by the sea. Then one of the leaders of the synagogue named Jairus came and, when he saw him, fell at his feet and begged him repeatedly, "My little daughter is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be made well, and live." So he went with him. And a large crowd followed him and pressed in on him. Now there was a woman who had been suffering from hemorrhages for twelve years. She had endured much under many physicians, and had spent all that she had; and she was no better, but rather grew worse. She had heard about Jesus, and came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, for she said, "If I but touch his clothes, I will be made well."

Immediately her hemorrhage stopped; and she felt in her body that she was healed of her disease. Immediately aware that power had gone forth from him, Jesus turned about in the crowd and said, "Who touched my clothes?" And his disciples said to him, "You see the crowd pressing in on you; how can you say, 'Who touched me?'" He looked all around to see who had done it. But the woman, knowing what had happened to her, came in fear and trembling, fell down before him, and told him the whole truth. He said to her, "Daughter, your faith has made you well; go in peace, and be healed of your disease." While he was still speaking, some people came from the leader's house to say, "Your daughter is dead. Why trouble the teacher any further?" But overhearing what they said, Jesus said to the leader of the synagogue, "Do not fear, only believe." He allowed no one to follow him except Peter, James, and John, the brother of James.

When they came to the house of the leader of the synagogue, he saw a commotion, people weeping and wailing loudly. When he had entered, he said to them, "Why do you make a commotion and weep? The child is not dead but sleeping." And they laughed at him. Then he put them all outside, and took the child's father and mother and those who were with him, and went in where the child was. He took her by the hand and said to her, "Talitha cum," which means, "Little girl, get up!"

And immediately the girl got up and began to walk about (she was twelve years of age). At this they were overcome with amazement. He strictly ordered them that no one should know this, and told them to give her something to eat.

I managed to make it all the way to my first semester at Princeton Seminary before I realized: I didn’t know how to read the Bible. I managed to get through confirmation as a high school junior. I managed to major in Religion at UVA. I managed to pass the entry steps in the ordination process without ever learning how to read the Bible.

When I started seminary, all first year students were forced to attend a weekend retreat. It was every bit as painful as that sounds. The Saturday afternoon of the retreat one of the leaders instructed us to get our Bibles and to find a place by ourselves somewhere on the grounds and have “quiet time with scripture.”

I had no idea what that meant.

So I asked her.

She suggested that I simply “turn to a random verse of scripture and meditate on it” (for the record: this is terrible advice).

So I did as she suggested. No joke, the first passage I turned to was Genesis 27 where what first caught my eye was: “Isaac did not recognize him, because his hands were hairy like his brother Esau’s hands...”

Which turned out to be hard to meditate on. So I turned a bit more in the Bible and what did I come to?

“Some small boys came up to Elisha and jeered at him, saying, ‘Go away, baldhead! Go away, baldhead!’ When he turned round, he cursed them in the name of the Lord. Then two she-bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys. From there Elisha went on to Mount Carmel, and then returned to Samaria.”

So I turned back a bit in the bible only to discover:

“Then the Lord opened the mouth of the ass, and it said to Balaam, ‘What have I done to you, that you have struck me these three times?’ Balaam said to the ass, ‘Because you have made a fool of me! I wish I had a sword in my hand! I would kill you right now!’

So I turned to the Gospels and I found Jesus telling me to hate my mother and my father. I turned further on back in the New Testament and it was all about circumcision.

I decided then that I didn’t know how to read the Bible.

The Bible is inspired, but the Bible is not a magic Ouija board that gives you whatever answer or uplift you need. There are right and wrong ways to read it. And Mark’s juxtaposed stories in chapter five are a good example of the three perspectives readers ought to bring to bear on every passage of scripture.

June 23, 2024

The Passion of the Truth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward— become paid subscriber!

Romans 1.18-25

Richard Taylor was an American philosopher and an internationally renown beekeeper. In his celebrated 1963 book Metaphysics, Taylor invites readers to imagine a man who is hiking in the woods and comes upon, out of the blue, a translucent sphere.

Obviously, Taylor points out, the man would be shocked by the strangeness of the object, and he’d wonder just how it should happen to be there, floating in the middle of the forest. More to the point, the hiker would never be able to swallow the notion that it just happened to be there, without cause or any possibility of further explanation. Such a suggestion would strike him as silly. But, Taylor argues, what the hiker has failed to notice is how he might ask that same question just as well about any other object in the woods—say, a rock or a tree or a spider web or a little boy—as about this strange sphere.

He fails to do so only because it rarely occurs to us to interrogate the mysteries of the things around us.

We’d be curious about a sphere suddenly floating in the forest, but as far as existence is concerned, everything is in a sense out of place.Taylor says you can imagine that sphere stretched out to the size of the universe or shrunken to a grain of sand, as everlasting or fleeting, and it doesn’t change the wonder.

As Taylor writes:

“This illustrates the fact that something that is mysterious ceases to seem so simply by its accustomed presence. It is strange indeed, for example, that a world such as ours should exist; yet few people are very often struck by this strangeness but simply take it for granted.

Suppose, then, that you have found this translucent ball and are mystified by it. Now whatever else you might wonder about it, there is one thing you would hardly question; namely, that it did not appear there all by itself, that it owes its existence to something. You might not have the remotest idea whence and how it came to be there, but you would hardly doubt that there was an explanation. The idea that it might have come from nothing at all, that it might exist without there being any explanation of its existence, is one that few people would consider worthy of entertaining.

The principle involved here has been called the principle of sufficient reason. Actually, it is a very general principle, and it is best expressed by saying that, in the case of any positive truth, there is some sufficient reason for it, something that, in this sense, makes it true—in short, that there is some sort of explanation, known or unknown, for everything.”

What does that all that mean?

It means every little detail and moment of our lives is a marvel no less than that sphere in the forest. It means every part of our lives together is a wonder of which we could ask, “Why this instead of nothing?” It means everything around us is not necessary at all, not “natural” unto itself, and as such, it’s charged, all of it, with the immediacy of God. It’s all gift. Everything, all of it, betrays the finger and foot prints of Almighty God, Maker of Heaven and Earth.

Everywhere God is up in our face.And yet from a great many of us, God gets our back.The word of the Lord fell upon the prophet Jeremiah, saying, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you.” The Lord appointed the prophet to preach to the people of Jerusalem about their impending doom, warning them that if they did not repent, their city would be destroyed and they would be carried away captive.

Unlike the reckoning preached by prophets like Jeremiah, Paul does not announce a pending possibility.According to the apostle, God’s wrath is already.Though the ancient heretic Marcion eliminated the word God from the genitival phrase, Paul’s epistle nevertheless reads, “For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who hold the truth imprisoned in the chains of their unrighteousness.” The apostle, unlike the prophets, proclaims God’s wrath after the fact. The Lord’s wrath is a present reality rather than a future judgment exactly because its revelation is the underside of the gospel.

Quite simply, the promise presupposes our plight.If the redemption of the cosmos required the death of God’s Son, if the law itself led God’s people to push him out of the world on a cross, if God will brook no good works of our own, then humanity’s bondage to sin is total and we are without hope.

In other words, in this passage, Paul essentially reasons that if the word of the cross is the good news, then the bad news must be bad indeed.This is why it’s a non sequitur to argue that the Old Testament lacks a doctrine of original sin. It does so necessarily, for humanity’s disordered depravity only becomes visible in light of the “now time” of the gospel; the gospel reveals human captivity even as it overthrows it. The world which crucifies God is precisely a world that God, in his wrath, has already handed over to its own desires, saying to the world, “Not my will but thy will be done.”

Having announced God’s powerful saving action in the gospel, here in the latter half of chapter one Paul takes up the gospel’s double meaning— namely, the unveiling of God’s wrath in the face of universal human rebellion against him. Starting in verse eighteen and extending all the way to the end of chapter three, Paul mounts an all-encompassing indictment of humanity that can account for the peculiar means by which the Lord makes us righteous, nude faith.

Paul begins his charging document by identifying a single sin under which all other sins are subsidiary.

We imprison the truth, as Karl Barth translates verse eighteen.And then Paul repeats the point three times in two verses. What is not visible is clearly visible. But we shut our eyes to the obvious. We suppress acknowledgment of God as Maker of Heaven and Earth. We break the first commandment which makes the keeping of all other commandments incidental.

In sum, the problem with the human condition is a failure to recognize the human condition; specifically, there is a God and you are not him.

You are the Creator’s handiwork and, as a creature, you are headed straight back to the dust from whence you came. So who in the hell are you to live as though you are in charge of your life? Or as Paul puts our problem, “They did not glorify or give thanks to God as God.”

Indeed shutting our eyes to the givenness of God— what Barth calls the Passion of the Truth, the suffering of the Truth— constitutes Paul’s only attribution of agency to human beings.

Just this week, a seminary student in the Midwest emailed me, asking, “I know that faith is a gift from God and salvation rests on faith alone. But I'm curious to know what you would say our role in salvation is— if any.”

And Paul answers her question here, “We suppress the truth of him who holds us in existence.”

In his book the Experience of God, my former teacher David Bentley Hart ridicules those who turn their backs to the God who shows up in our face everywhere, everyday.

Hart writes:

“An absolutely convinced atheist, it often seems to me, is simply someone who has failed to notice something very obvious—or, rather, failed to notice a great many very obvious things…It may be that the atheist lacks not any conceptual means but rather the very experience of existence itself.

Just to make clear what my peculiar prejudices are, I acknowledge up front that I do not regard atheism as an intellectually valid or even cogent position; in fact, I see it as a fundamentally irrational view of reality, which can be sustained only by a tragic absence of curiosity or a fervently resolute will to believe the absurd. More simply, I am convinced that the case for belief in God is inductively so much stronger than the case for unbelief that true atheism must be regarded as a superstition, often nurtured by an infantile wish to live in a world proportionate to one’s own hopes or conceptual limitations.

Atheism misses the whole point of talk of creation: God would be just as necessary even if all that existed were a collection of physical laws and quantum states, from which no ordered universe had ever arisen; for neither those laws nor those states could exist of themselves.”

That is to say—

Even if God had never spoken the stars into the sky nor brought you to be, the simple math to compute the tip on your restaurant tab logically necessitates the existence of God.That 1 + 1 = 2 is by itself sufficient reason to believe, an argument from design.Everywhere the fact of God is up in your face.

And, more often than not, God gets our back.

But, to make this a matter of philosophical diversion only exacerbates the indictment with which Paul accuses all of us.

To believe or not to believe—

It is not the stuff of speculation.

It is a question whose answer, so to speak, has the ability to alter our DNA.

For Paul, the correlative to sin is not the law but creation.Much like the Book of Proverbs, which rarely speaks of sin in reference to a moral code, Paul can begin by indicting all of humanity, most of whom have not the law, because sin is more fundamentally a disordered response to reality.

All sins are secondary to our overarching failure to acknowledge God as Creator.Paul takes it as obvious that the beautiful world and the goodness of life comes from a Giver— life is as incontrovertibly miraculous as a blue sphere suspended before you in the forest. Just so, to express one’s gratitude to that Giver is not only right and beautiful in itself but an indication that one is properly ordered to— in tune with— the goodness of creation. Hence, sin is far more egregious than the violation of rules and deeply more problematic than “missing the mark.” It is, in Paul’s terms, a suppression of and willful blindness toward the obvious truth of human dependence on God. We did not make our world. You did not create your child. And when we defy its order and goodness with our greed, malice, slander, lust, etc., when we make ourselves the arbiters of life, we assume the right of creators to define the terms of their own existence.

Such is the lie— the passion of the truth— implicit in every sin.

Moreover, to fail to practice gratitude to the Giver is to show oneself insensitive to, and at odds with, creation’s goodness, an aberration from which inevitably other perversions of goodness follow, infecting and corrupting every aspect of life.

This is the straightforward claim in the passage.

As the American Standard Version renders it:

“For revealed is a wrath of God from heaven against all impiety and unrighteousness of men who hinder the truth in unrighteousness, because that which is known of God is manifest in them, for God manifested it to them. For the invisible things of him since the creation of the world are clearly seen, being perceived through the things that are made, even his everlasting power and divinity, that they may be without excuse. Because, knowing God, they did not glorify him as God, nor give thanks, but became vain in their reasonings, and their senseless hearts were darkened.”

We speak of the worship of God as though its a simple matter of Sunday morning attendance and that the decision to stay home, play golf, or heed the demands of travel sports is a morally neutral choice. Meanwhile, according to scripture, when God is not worshipped and glorified the primary faculties of our thinking and perceiving become distorted, “their senseless hearts were darkened.”

When God is not worshipped and glorified the primary faculties of our thinking and perceiving become distorted

If Paul were writing to the church today, he might say that the failure to worship God as God permanently altered our DNA because his precise point here is that the corrupting effects of the fall are as irreversible as they are universal. We were all born into a world downstream of Paul’s diagnosis. You can post the Ten Commandments in every room in the world and it will not matter. It will not make us righteous. It cannot lighten and enliven our hearts— that darkness cannot be undone. Just as there are no excuses, there is no hope. Knowledge of the true God, exclusive worship of him alone, obedience unto him and no other, those possibilities are gone. They disappeared for you before you entered the world. Human nature cannot now recover because, somewhere east of Eden, God gave us over to what we want.

THERE IS NO HOPE.

Writing on the first commandment, Robert Jenson restates the underside of Paul’s gospel:

“In Genesis’ account of creation, the great theme is: “God said, ‘Let there be . . . .’ and there was . . . and it was good.” God speaks Torah even where there is nothing, and even so is obeyed; the existence of creatures is exactly this obedience. To hear God’s command is, therefore, to be refreshed in my very being.

It follows that not to obey God’s commandments is not to be. It would seem further to follow that if I once am disobedient, I cannot again obey, there now being no one there to do so. And these are indeed the drastic truths: sin is death, and renewal of obedience demands nothing less than new creation.”

This should not be a surprising claim.

Of course! Rejection of the One in whose image we are made corrupts human nature to its vanishing point.

Of course! Rejection of our creature-hood makes us less than human.

Of course! Our nature being so corrupted we engage in acts whose wrongness should be as obvious as the philosopher’s sphere.

This past week the Wall Street Journal published an article by Katherine Blunt entitled, “The Influencer Is a Young Teenage Girl. The Audience Is 92% Adult Men.”

If you blanche or hesitate at Paul’s totalizing indictment, I encourage you to read it.

In it, Blunt reports on a Midwestern mother who, three years ago as a pandemic-era diversion, started an Instagram account for her preteen daughter. A former marketing director, the mother thought that she and her daughter could bond by sharing photos of the girl dancing, modeling, and living life in small town America.

Quickly, the mother’s daughter amassed followers. Soon, photographers offered to take professional shots for the girl. Not long after, brands began sending free apparel for the girl to model.

“We didn’t even have the page for a month, and brands were like, “Can we send her dance-wear?’” the mom said. “She became popular really fast.”

Unsurprisingly, the mom eventually noticed a disturbing trend in the data that showed up on the Instagram's account dashboard.

Most of the preteen girl’s followers were older adult men.

Men left public comments on photos of the girl with fire and heart emojis, telling her how she was gorgeous.

Other comments, direct messages, photos, and links left by adult men I cannot utter here.

The girl’s mother told the Wall Street Journal reporter that soon after starting the Instagram account, she had to devote two to four hours a day to blocking followers or deleting inappropriate comments.

At the same time, the mother excitedly counted the sponsorships and brand deals and money that came their way.

With her mother’s encouragement, the girl announced that her “dream job” in the future when she became an adult was to become an influencer.

The girl’s mom explained to the reporter, “It wasn’t like I was trying to push her to be a star, but part of me thought it was inevitable, that it could happen someday. She just has that personality.”

And the mom divulged to the reporter that her daughter’s aspiration's left her in a bind:

“To reach the influencer stratosphere, the account would need a lot more followers—and she would have to be less discriminating about who they were. Instagram promotes content based on engagement, and the male accounts she had been blocking tend to engage aggressively, lingering on photos and videos and boosting them with likes or comments. Running them off, or broadly disabling comments, would likely doom her daughter’s influencer aspirations. That was a reason to say no. There were also reasons to say yes. The mom felt the account had brought her closer with her daughter, and even second- and third-tier influencers can make tens of thousands of dollars a year or more. The money could help pay for college, the mom thought.”

The mom said yes.

And with that, she grew to accept a grim reality: Being a young influencer on Instagram means building an audience including large numbers of predators. . . .

Katherine Blunt’s reporting then goes on to document how the girl’s Instagram account became so entangled with profanity and predation that it’s parent company Meta— not the girl’s mother— shut down the account. The article ends with mother and daughter expressing regret and relief.

Regret that Instagram removed the girl’s account.

And relief— relief that they had created a backup account.

“…they became vain in their reckonings, and their senseless hearts were darkened.”

You do not need a commandment that explicitly states, “Thou shalt not pimp out your daughter before pedophiles,” to know that it’s wrong.That girl’s mother has no excuse.Nevertheless, even as we judge the girl’s mother in our hearts, Paul’s charging document does not stop until every last one of us is caught in its indictment.Raise your hands (in your hearts) if this accusation fingers you:

“Since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up to a debased mind and to things that should not be done. They were filled with every kind of wickedness, evil, covetousness, malice. Full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, craftiness, they are gossips, slanderers, God-haters, insolent, haughty, boastful, inventors of evil, rebellious towards parents, foolish, faithless, heartless, ruthless. They know God’s decree, that those who practice such things deserve to die—yet they not only do them but even applaud others who practice them.”

When Paul finally wraps up this indictment with the words, “There is no distinction…all have fallen short of the glory of God…” he’s breaking the news that there is NO HOPE FOR ANY OF US.

There is no hope. Forget about being saved by God. We cannot even know the true God with our darkened hearts and debased minds.

THERE IS NO HOPE.From our side.That’s the underside of the gospel.Turn it over though…Our only hope is that it’s true.Our only hope is that this little word, not nearly as obvious and obtrusive as the philosopher’s blue sphere, is true, “Jesus lives for you.”With our darkened hearts and debased minds, this little word— this little word, not the golf course and not purple mountains’s majesty— is the only place the true God can be found. And your faith in it is your only escape from the wrath of God we are already in.

So come to the table.

You have sufficient reason.

The bread that is his body and the wine that is his blood— the creatures of his promise to you for you— are not only your righteousness, they are your rehabilitation.

Eating, in faith, alters your DNA.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 22, 2024

It All Starts with Grace

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Hi Folks,

Here is the first session of our dive into Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics II.2, the Election of Jesus Christ.

If you’d like to read along with us, a few pages at a time, here is the text:

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadAnd here is the link to join us live on Mondays at 7:00 PM EST.

Show NotesSummary

The conversation explores Karl Barth's doctrine of election and grace within the doctrine of God. The participants discuss the significance of the prologue to John's Gospel and how it relates to the doctrine of election. They highlight Barth's Christological orientation and his emphasis on the triune identity of God. The conversation also addresses the problems that arise when our first assumption about God is not triune and how Barth's understanding of election and grace challenges traditional views. The participants emphasize that election and grace are personal and relational, not abstract concepts. In this conversation, the participants discuss the concept of God's election and its implications for understanding God's character and human identity. They explore how the doctrine of election challenges the idea of a transactional God and emphasizes the relational nature of God's love. The conversation also touches on the importance of Jesus as the embodiment of humanity and the need to redefine freedom in light of Christ's obedience to the Father's will. Overall, the participants highlight the significance of understanding God's election as an unconditional act of love that invites humanity into a shared life with God.

Takeaways

Karl Barth's doctrine of election and grace is centered on the triune identity of God and the person of Jesus Christ.

The prologue to John's Gospel is significant in understanding the doctrine of election and the relationship between God and humanity.

Barth challenges traditional views of election by emphasizing the personal and relational nature of God's grace.

Election and grace are not abstract concepts, but a declaration of God's love and invitation to participate in his life.

Understanding election and grace leads to a deeper appreciation of the gospel and the inclusive nature of the church. God's election challenges the idea of a transactional God and emphasizes the relational nature of God's love.

Understanding Jesus as the embodiment of humanity helps redefine our conception of human identity.

Freedom, in the Christian sense, is not about autonomy and self-fulfillment, but about embodying God's will.

God's election is an unconditional act of love that invites humanity into a shared life with God.

Sound Bites

"The doctrine of election, that doesn't sound scary. But the doctrine of predestination, all of a sudden people's sphincters get tight."

"Barth will not allow any God talk to happen that is speculative and abstracted apart from how God has acted in history."

"God and Jesus are very tight."

"There's a whole lot of God talk that exists in Christian culture that the God that is spoken of does not resemble Jesus Christ or the one he calls father."

"Barth is a good corrective for those of us who like to hear ourselves talk. And we Baptists love to hear ourselves talk."

"We lose the first person address of God in Christ saying to us, 'Look what has been done. Look what I have done.'"

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 21, 2024

Therefore, I Despise My Words

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber1

The alternate Old Testament lectionary text for this Sunday is God’s address of Job from the whirlwind:

Then the LORD answered Job out of the whirlwind: "Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Gird up your loins like a man, I will question you, and you shall declare to me. "Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements--surely you know! Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone when the morning stars sang together and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy? "Or who shut in the sea with doors when it burst out from the womb?-- when I made the clouds its garment, and thick darkness its swaddling band, and prescribed bounds for it, and set bars and doors, and said, 'Thus far shall you come, and no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stopped'?

Job 38.1-11

It is this display of ineffable, incomprehensible almightiness that finally quiets the complaints of Job.

You know the story.

Job, a man in the land of Uz, a man blessed with seven sons and three daughters, a rich man in possession of seven thousand sheep and five hundred yoke of oxen, a righteous man, blameless and upright who feared God above else, by providential decree, Job loses everything. His estate is taken from him by marauders. His home is burned by fire. His family is killed by a devastating wind.

And then, Job is plagued by a contagion and sores erupt all over his body. To make matters worse, in his suffering, Job is consoled by three insufferable friends who dispense pieties and the cold comfort of explanations.

Eventually Job explodes, indicting God for His poor job performance, “Oh that I had one to hear me! Here is my signature! Let the Almighty answer me!”Job registers his grievances for thirty-five long chapters in the Book of Job. From chapter three to chapter thirty-eight, the book is nothing but Job complaining about the cosmic injustice he’s suffering and petitioning for a lawsuit hearing against God.

It’s important to point out that despite its reputation as such, the Book of Job is not an attempt to explain the mystery of suffering.

“Why do bad things happen to good people?” is not a biblical question because, as Jesus himself says, “No one is good but God, alone.”Nor does the Book of Job intend to answer the other very modern question about God’s existence,“Is there a God given a world of such suffering?” The Book of Job simply sets to the side the question of what merits our suffering, and God’s existence is taken for granted in the book; in fact, God is the active agent of everything in the book.

The Book of Job is not an explanation.

The Book of Job is a rage against explanation.

Job does not receive the reasons for his suffering.Job receives a revelation.And, to the incredulity of many modern readers, that’s enough for Job.God finally responds to Job’s indictments by appearing amidst a whirlwind summoning Job to behold not his own situation but the Creation, itself.

Taken on one level, God’s mighty address in reply to Job’s complaints sounds extraordinarily irrelevant. God never gives Job the response Job has sought. But taken on an altogether different level, God’s reply from the whirlwind renders the questions to which Job has sought answers obsolete.

God’s answer for Job is no answer at all, yet it satisfies Job totally.Job forgets all his sufferings and grievances. Job abandons all the many words he has uttered over thirty-five chapters. Job replies sparingly to the Lord’s interrogation:

“‘I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. Therefore, I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know.”

God condescends. God comes to meet Job, the grandest scene Job has ever witnessed. In great power, in a display of godawful almightiness, the Lord reveals Himself to Job in a whirlwind, and that revelation reconfigures everything for Job.

Job has pleaded with God for answers about his trials and hardships, but now, face-to-face with the greatness of God, Job’s suffering is incidental to the point of no longer being interesting to him. God, says Fleming Rutledge, gives Job not answers or explanations, but a new epistemology; that is, a new way of knowing, a new way of seeing the world and his place in it.

“I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore I despise my words.””

And Job says no more.

In his commentary on the Letter to the Philippians, Karl Barth posits that Paul’s surprising and memorable declaration, “For to me, living is Christ and dying is gain,” should be understood alongside God’s self-revelation to Job. What Paul attests from his cell should be heard in conjunction with how Job responds to God’s address from the whirlwind.

As the circumstances of the letter make clear, the church at Philippi has heard the news that the Apostle Paul has been arrested and sentenced to prison in Rome. His status as a Roman citizen exempted Paul from crucifixion, but his citizenship would not spare him from the executioner’s sword. The Philippian congregation had learned of Paul’s situation, and, in all likelihood, they intuited the suffering and death that lay in Paul’s future.

As the letter makes clear, they have written to Paul to inquire about his suffering. They’re worried for Paul. And, counterintuitively, Paul replies by talking about himself and his suffering not at all.

“For to me,” Paul writes in reply, “living is Christ and dying is gain.”

Paul doesn’t give them the answers they have sought. The Philippians have asked about Paul’s situation. Paul answers instead about the situation of the Gospel. “I want you to know, beloved,” Paul writes, “that what has happened to me has actually helped to spread the gospel, so that it has become known throughout the whole imperial guard and to everyone else that my imprisonment is for Christ…What does my suffering matter? Just this, that Christ is proclaimed in every way, whether out of false motives or true; and in that I rejoice.”

“To live is Christ, and to die is gain.”Can you imagine someone who has lost everything responding to an inquiry about their situation with, “To live is Christ, and to die is gain?” Can you imagine their loved ones saying to them, “To live is Christ, and to die is gain?”

Of course not. You’d think them callous or crazy.

What accounts, then, for Paul’s ability to center his life and death wholly in Christ and to center his concern not on his life or death, but on the advancement of the Gospel?

Paul, don’t forget, has lost nearly as much as Job. He’s lost his status and the community that came with it. He’s been beaten and scorned. He’s been rejected by those Christ called him to lead. He’s been shipwrecked, attacked by lions, and arrested at least three times. He’s lost his sight, and now he’s about to lose his life. But all he cares about is the spread of the Gospel, for “To live is Christ, and to die is gain.” Like Job, Paul has lost much. And like Job, Paul has suffered mightily— he bears the wounds of Christ in his own body, Paul writes to the Galatians.

But like Job, Paul has been encountered by the power and majesty, the godawful almightiness of God, and it has reconfigured everything for Paul.When Karl Barth saw the Christians of his own time and place succumb to the idols of nationalism and nativism and racism, he said the only antidote was for the Church to rediscover “the God-ness of God.”

Having shaped God into our image, Barth meant, the Church needed to be encountered once again by the incomprehensibility of God— the God who reveals Himself from the whirlwind.

The God who cannot be conjured up by our own projections and imaginings.

The God who can only be known by us through revealing Himself to us.

Like Job, Paul has been encountered by the God-ness of God.

The God of wind and storm, fire and flood, the God who is “infinitely greater than the sum of all natural phenomenon put together,” the God who knows the number of the hairs upon your head and when the mountain goats give birth— That is the same God who reveals Himself to Paul in the resurrected flesh of the crucified Christ.

The God of the Whirlwind has revealed Himself to Paul as the Man of Sorrows. Like Job, Paul has been encountered by the Comforting Whirlwind. The treasure in the field has found him. The pearl of great price has obtained him at great cost. And, whereas, Job departs the whirlwind mute over the greatness of God, Paul rests in prison absolutely loquacious about the grace, such that, the advancement of the Gospel is now the entire meaning and measure of his existence, compared to which his own imprisonment is no longer very interesting.

He’s been given a new epistemology, a new way of knowing, a new way of seeing the world and his place in it. And his place in the world— your place in the world— is in Christ.

Paul doesn’t mean that metaphorically.

That’s why he can say, “To live is Christ, and to die is gain.”

Living or not, on account of Jesus Christ, your true location in God’s Creation will not change, cannot change. As Paul tells the Colossians, your life is hidden with God in Jesus Christ. You belong to Christ, Paul writes in 1 Corinthians, and Christ belongs to God; therefore, death holds no terrors. There are no Christians in hell, because all are already and forever in Christ.

And because you are in Christ, Paul tells the Corinthians, the only difference between life and death is that in death you will see what now can only be known by faith. This is the sense in which Paul can speak of death as “gain.” Or, as Paul puts it to the Roman church, “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us.”

Notice the connection—

Our future is incomparable because it is in Christ Jesus who is himself the God beyond comprehension.

If Job leaves from his encounter with the Lord with every single one of his questions still unanswered, then there are many questions to which this mortal life will not yield answers. Of course, if God had given us an explanation for the suffering of the world, then, as Stanley Hauerwas says, we should worship that explanation.

Instead God the Father has given us his Son and the Son has given us his Spirit, three-in-one, the blessed Trinity, an incomprehensible reality which nevertheless meets us in the Word, in Water and Wine and Bread and which may— just wait and see— reconfigure all your questions.

From his own prison cell in Nazi Germany, the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote to a friend, “Only the Suffering God can help us.”

He was talking about the God-ness of God.

Only the God who is beyond our understanding, a carpenter born to Mary who yet knows the time the mountain goats give birth, can save us.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 20, 2024

Paul Zahl on the Generous Genius of Jürgen Moltmann

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber. Much love to those who do!

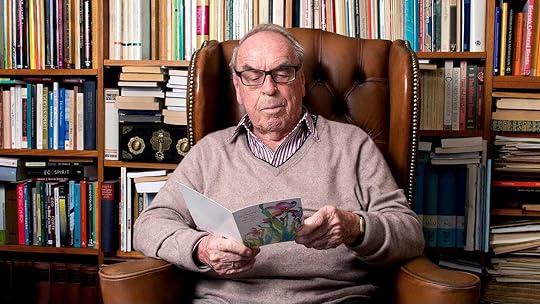

Here is a conversation I recently shared with author and Episcopal priest Paul Zahl, the last overseas student of the late Jürgen Moltmann.

Here is the tribute PZ wrote for Christianity Today.

Show NotesSummary

The conversation between Paul Zahl and Jason Micheli covers various topics, including Paul's trips to the Outer Hebrides and the North of Scotland, his recent trip to Germany for Jurgen Moltmann's funeral, and his experience studying under Moltmann at Tubingen. They discuss Moltmann's influence on Paul's work, his theology of liberation and hope, and his book 'The Crucified God'. They also touch on the changing expectations of funerals and the importance of personal and truthful services. In this conversation, Paul Zahl and Jason Micheli discuss the importance of funerals and the need to focus on the gospel rather than the individual being eulogized. They share their pet peeves about self-indulgent sermons and emphasize the importance of a brief, personal, and gospel-centered service. They also discuss the theology of Jürgen Moltmann and his belief in the sources of Trinitarian Christology. Zahl shares his personal experience of studying under Moltmann and the impact it had on his understanding of justification and the love of God for the ungodly. They also touch on the transition in Paul's letter to the Romans and the need to recognize the brokenness and lack of hope in the world before the gospel can truly be understood.

Takeaways

Paul attended Jurgen Moltmann's funeral in Germany and wrote a moving tribute to him in Christianity Today.

Paul studied under Moltmann at Tubingen and learned about his theology of liberation, theology of hope, and his book 'The Crucified God'.

Funerals have changed over time, with a shift towards more personal and truthful services. Funerals should focus on the gospel rather than the individual being eulogized

Self-indulgent sermons should be avoided, and the service should be brief, personal, and gospel-centered

Jürgen Moltmann believed in the sources of Trinitarian Christology and rooted his theology in his own experiences of suffering

The love of God is for the ungodly, and understanding this is key to grasping the gospel

Recognizing the brokenness and lack of hope in the world is necessary before the gospel can truly be understood

Sound Bites

"I was so terribly impressed by the extraordinary trips that you took with your family to the Outer Hebrides and the North of Scotland."

"You are one of the voices associated with justification by faith. Jurgen Moltmann had a voluminous output of work."

"I really wanted to do something new. I really wanted to study justification by faith."

"I mean, you really wanted to stay, if this is a funeral, I'd rather go to, I don't know what."

"We seldom invite the dead to their own funerals."

"The sermon was pure gospel, pure gospel."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 19, 2024

The Problem with Salvation as Process

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber. Much love to those of you who do!

Continuing my thoughts from a previous entry on Historical Faith vs. Lively Faith…

The Reformation slogan that we are justified by faith alone is a stipulation about the special hermeneutical character of the gospel as a mode of discourse.

For the gospel to be gospel, to preach the gospel as gospel, it must be promise and not exhortation if it is to be an apocalyptic word from and existential encounter with the living God. Whereas historical faith treats Christ’s identity and the event of his incarnation as items of the past, lively faith is lively exactly because the gospel is the way God has elected to do address us.

Lively faith is the wound left behind by God’s self-disclosure in the word.Historical faith is the acquisition of information about God’s work and the addition of our own acts to it.The distinction is necessary because the abuse that Luther et al sought to resist was the church speaking about the forgiveness of sins and justification to righteousness as though they depended on conditions controllable by us— as matters of law.

Thus, Robert Jenson argues:

In other words, historical faith turns preaching into a data dump.“Discourse about Christ then becomes the provision of information, historical speech about him, lacking any unique existential function, a transfer from one head to another of information, which can be possessed without personal transformation.”

And indeed a great deal of “preaching” in the church today is the transfer of information. Instead of sermons, the church offers “teachings.” Rather than messages (kerygma), the church communicates “lessons.” Though Wisdom literature makes up very little of the canon, it is ubiquitous in the church.

The perniciousness of historical faith is that this information transfer and its correlative summons to respond on its basis is done as a process leading to salvation where a must happen for b to be possible and b must happen for c to be possible and so forth. Of course God will be credited as the primary protagonist of this process but, clearly, I must do something if I am not to be left out of the event of my own salvation.

Once again:

The difference between historical and living faiths is not between two responses to one message, but between the responses to two different messages:

“Christ died for the world, and now this is how you get into the result of his death”

Versus

“Christ died and now lives for you.”

The latter leaves you with no possible recourse but faith.

The former posits conditions that are precisely what the Reformers attacked, presenting a proclamation of Christ that itself turns into new exhortation and directs people back to their own fulfillment of— in themselves, necessary— moral and religious standards, to find therein the ground of their confidence in God.

Historical faith, posits salvation as a process where we are necessary counterparts to God.

Just so—

As common as it is to speak of salvation as a two-party process or a synergistic journey or a dance between partners, this is the gospel’s undoing.

As Jenson notes:

“If I understand my final relation to God as the outcome of a process which can at certain points stop if my contribution fails, and precisely if I am assured of God’s grace, that is, that his contribution can be relied upon, my contribution or its failure makes the whole difference in my life.”

My contribution or its failure makes the whole difference in my life.

That is—

If salvation is a process, then you are god.Jenson observes that the Reformers rightly saw in historical faith (“Christ died for the world, and now this is how you get into the result of his death”) nothing but a choice of damnations:

“If the hearer remains unconcerned, that is, unbroken in his alienated assumption that the reasonable conditions of salvation process’s completion are in his control, spiritually empty works-righteousness is the result. If, alternatively, this teaching encounters a “troubled conscience,” it works damnation. If the law enters that realm of endlessly uncontrolled ambiguity called the heart and so demands not this or that civil work but love and hope, the hearer’s situation is desperate and can be saved only by promise.

For the heart’s law cannot be obeyed by one who in any way already is and knows himself a sinner: all lawlike talk “accuses his conscience and terrifies him,” and the flight from God thus imposed is the opposite of loving obedience, even when the flight takes the form of religiosity. If then the teachers of the Church bring no different kind of message from God, if also their talk about Christ is legal in its logic, all is lost.”

If the gospel is not gospel and all our speech about salvation in Christ is ultimately legal in its logic, then not only do we not have a gracious God but we are finally the gods in control of the process.

And we are fickle gods indeed.

(art: “Preacher Man” by Chris E.W. Green)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 18, 2024

Historical Faith vs. Lively Faith

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward— become a paid subscriber!

The church, Robert Jenson writes, is “the community of a certain communication.”

But what precisely is this communication?

As I mentioned in my sermon on Romans 1, I recently preached for a congregation in Southern California. And after the morning service, a parishioner embraced me and thanked me on the way out. “Thank you for preaching the gospel,” she said, “Forgiveness. On account of Christ. For you. I heard it last Sunday and I’m so relieved you handed it over this Sunday.”

I count any preacher lucky who has a listener attuned to the gospel, but I wonder if this parishioner was correct to limit her expectations to only seven words, the very same formulation she had received the prior Sunday, “Forgiveness. On account of Christ. For you.”

There are preachers and hearers who believe that if they’ve not uttered or received a particular recitation of a biblical construal of God’s work in Christ, then the gospel has not been handed over or heard.

Jesus died for you.

The shed blood of Christ can save even a Christian.

He was raised for your justification.

The problem with this premise is that it leads inexorably to Pelagianism, the heretical judgment that salvation is a process to which I contribute a subsidiary but nevertheless key component. If proclaiming the gospel amounts to little more than the repeating of scriptural definitions and Sunday School formulas, then it is nothing more than the positing of a past event. In which case, proclamation is an echo of what God did and not an announcement in which God does.

To limit the gospel to historic slogans of a past event also flatly contradicts the dogma straightforwardly established by the Council of Orange in the sixth century:

Salvation is God’s work not ours.If the ecumenical council at Orange is indeed binding— and it is, then proclamation must therefore be a mode of communication, free of past formulations, in which God is the active agent of address.

Thus Jenson stipulates an expansive definition for gospeling. The gospel is the story about Jesus and Israel, he insists, told in the register of promise.

Jenson offers an example:

“Jesus the crucified Israelite is risen and lives with death behind him; therefore, nothing can now overcome his will for you. Your future is in his hands and no other. There is reason for all your struggles.”

For the Council of Orange’s dogma to hold, God must be the one who addresses us in the gospel. Thus, the criterion for whether or not our speech about Christ is gospel is not the presence of precise words and phrases from scripture but whether or not it is:

Promissory in nature

Sets sinners free for the future.

For Jenson, there is a difference that makes all the difference, a difference that cuts to the heart of the Reformation’s protest against medieval abuses of the gospel. It is the distinction between historical faith and lively faith.

“Mere” historical faith refers to the possession of true information about Christ. Historical faith treats Christ’s identity and the event of his incarnation as items of the past. Love, then, easily becomes the needed liveliness added to historical faith, “You believe. That is good. Now produce appropriate works of love.”

In the course of their defense of the sola fide, Jenson notes that the reformers advanced a unique distinction between historical faith and lively faith:

Lively faith is lively exactly because the gospel is existential encounter with the Risen Christ who addresses us in the proclamation.

“There is of course nothing wrong with the exhortation to love, even to love because we would be faithful. But if its slogan, fides caritate formata, is made the formula for what justifies, then in its churchly function it becomes a slogan for precisely what the Reformers attacked: a proclamation of Christ that turns into new exhortation and directs people back to their own fulfillment of—in themselves, necessary—moral and religious standards, to find therein the ground of their confidence before God.

If we turn now to the Reformers’ distinction between historical and living faith, we perhaps expect to find a similar pattern, with some personal quality—though perhaps, for example, sincerity instead of love—stipulated as a needed supplement to historical faith. But in fact the Augsburg Confession makes a wholly different kind of distinction: “historical faith” is apprehension of the mere “history” of Christ; “living faith” is apprehension of the promise made by those histories when proclaimed as done for us.

If my faith is merely historical, the problem is not that I lack a personal quality but that the essential point of the gospel has not gotten through to me—perhaps because the Church did not make it.

And thus we come to the true function of the Reformers’ distinction.

The difference between historical and living faiths is not between two responses to one message, but between the responses to two different messages:

“Christ died for the world, and now this is how you get into the result of his death”

Versus

“Christ died and now lives for you.”

“We are justified by faith alone” is not a stipulation about the anthropological conditions of justification, but about the special hermeneutical character of the gospel as a mode of discourse: that it must be promise and not exhortation if it is to be the creative word from God that sets lives right.

So then, the church cannot limit the gospel to its past iterations. The gospel is free to set us free from every bondage to the past and to every static status quo. To be itself, in which the Word addresses us in the present, the gospel must “speak to the living hopes and fears of its actual hearers; to be itself, the gospel changes.”

The gospel changes. This is the gospel’s all-encompassing power which Paul extols in Romans 1.16.Just so—

Because the gospel is a living word for lively faith, far from merely repeating the same verbal formulas week in and week out, the gospel can never be preached the same way twice.

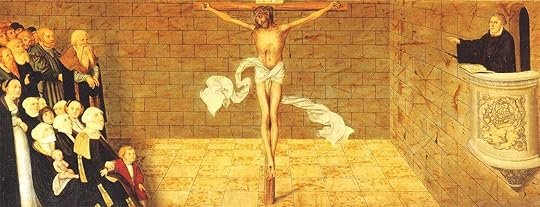

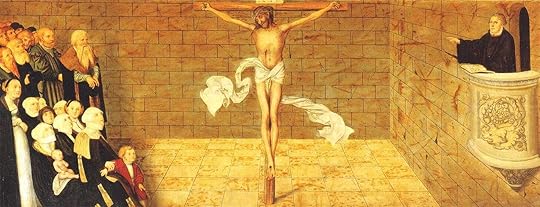

(Lucas Cranach the Elder, “Law and Gospel”)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 17, 2024

The "I" that A.I. is Missing

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Happily, this space has many more readers than it did when I first wrote this piece. At the time, I had not expected (I’m an idiot) the mainline church uncritically to endorse and adopt A.I. for preaching and worship planning. Etc. If only there are had been some churches featured in the Terminator or if an onboard chaplain had been included in the cast of 2001: A Space Odyssey, then perhaps we would not make haste to join the Borg.

For shits and giggles, my friend Ken Jones recently asked ChatGPT to “write a sermon on Romans 5.1 in style of Jason Micheli.”

ChatGPT is the artificial intelligence portal that has occasioned much leery hand-wringing of late. In moments, A.I. can scour the available data in the digital square and assemble a relevant string of facts and propositions, and, importantly, it can do so in what appears to be the proper rhetorical form. For the uninitiated, the preacher’s work of attending to the coming Sunday’s scripture, exegeting his or her own congregation, listening for a word from the Lord, and only then writing down a sermon that will be God’s own living word is long, slow, labor-intensive work. And very often it ends in failure. ChatGPT, by contrast, can produce a passable facsimile of a sermon in moments.

A.I.’s implications for those who work with words have not gone unnoticed.

For example, here is the sermon ChatGPT spit out in seconds in response to my friend’s request:

Dear friends,

Today, I want to draw your attention to the words of the Apostle Paul in Romans 5:1, where he writes, "Therefore, since we have been justified through faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ."

These words carry a profound message for each one of us, a message of hope and assurance in the midst of our struggles and trials.

You see, Paul's words remind us that our justification before God is not based on our own merits or works. We do not earn our salvation through our good deeds or righteous living. Instead, it is through our faith in Jesus Christ that we are justified and made right with God.

This is a message that runs counter to the prevailing wisdom of our world, where we are told that we must earn everything we have through hard work and dedication. But the truth of the Gospel is that our salvation is a gift freely given by God, and it is through our faith in Jesus that we are able to receive it.

Through our justification in Christ, we are able to experience peace with God, a peace that surpasses all understanding. No matter what challenges we may face in our lives, we can rest assured that we have a God who loves us and who has already won the victory for us.

So let us hold fast to our faith in Jesus, trusting in the power of his death and resurrection to bring us into a right relationship with God. And let us live each day with the confidence that comes from knowing that we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.

May these words of Paul be a source of comfort and strength to each one of us, now and always.

Amen.

Preachers should loosen their sphincters and admit that not only is this shockingly not bad so far as sermons go but it’s also depressingly better, in terms of cogency and observance of the text, than what many listeners would likely suffer from their flesh-and-blood preacher in a sermon on the same scripture. For instance, A.I. avoided the urge to deconstruct the problematic Paul, turn the apostle’s theology into anthropology, or truck in contemporary politics or ecclesial concerns under the banner of “struggles and trials.” Ilúvatar be praised that A.I. doesn’t yet seem acquainted with the New Perspective on Paul.

The surface limitations of ChatGPT are straightforwardly simple to spot. I certainly have enough of a digital footprint for my friend’s request (“in the style of Jason Micheli”) to have been somewhat replicable. Yet no one who has heard me preach would believe I would bring such a paltry word count into the pulpit nor would I ever begin with a salutation (“Dear friends”) that is as limp as it is false. Just ask my church— they’re not all my friends. Some of them don’t like me. They’re only there because Jesus, who is not dead, has arranged our relationship.

Most critical, while A.I. appears able to spit out intelligible thoughts about God from a passage of scripture, ChatGPT appears to know not the purpose of proclamation. You can spot the fatal error in the move to hortatory at the end, “Let us hold fast to our faith in Jesus…”

It’s a “lettuce sermon.”

It’s a sermon exhorting its hearers to do.

This is deliciously ironic for a scripture on justification by faith alone.

Nonetheless, again embarrassingly so, this is an error that many (most?) incarnate preachers make every Sunday.

Ask ChatGPT for other homiletical offerings on different biblical passages and you will discover A.I. can perform accurate exegesis, provide clear statements about the Bible and its implications for daily living, and speak in relevant terms about the God narrated therein. None of these offerings, however, constitute proclamation.

And this is precisely the irremovable impoverishment of A.I. preachers.

Straightforwardly, the gospel is promise from Christ through a person to a person.Promise is the way the Living God words the world.Proclamation is not simply any word about God. If you have merely explained a biblical text, spoken on a scriptural theme, or talked about God (from the safe remove of second-order discourse), you have, quite simply, not proclaimed the gospel. Thus, you have shuttered the lips of the otherwise loquacious God. Once again, sadly, many incarnate preachers seem to be as ignorant of their primary task as ChatGPT.

The proclamation of the gospel is a promise from Christ spoken through a preacher to a sinner.

As Robert Jenson writes in Story and Promise:

“What happened to the world with Jesus was that at the end of the long history of Israel’s promises, a sheerly unconditional promise was said and became sayable in the world.”

In other words, because the Lord Jesus is risen, every passage of scripture functions as gospel. Therefore, the task of proclamation is not explanation. The task of proclamation is unconditional promise. Every preacher must ask of every passage not “What does it mean?” or “What can I say this Sunday?” or “How is it relevant?” but this question:

“What does the text promise and what may I thus promise that can be and only can be because Christ lives?What future, possible and certain on account of Christ, may I promise my hearers by the leading and authority of this text?”

Again, proclamation is not merely a report about or even an announcement of this unconditional promise. Preaching is a providential “speech-act,” the realizing of the Word by and in our speaking and our hearing. A sermon, in other words, does not merely say that Christ is risen; it enters into and makes available to others the reality of his resurrection. And the way in which the reality of Christ’s resurrection becomes available to us is in an embodied promise that can only be uttered if Jesus has death behind him.

The most basic way the reality of Christ’s risen-ness becomes available to us is in the office of the keys, “I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of your sins…”This is the I that A.I. is missing and will never possess.This most basic form of gospel proclamation shows forth ChatGPT’s most basic deficiency as a writer of sermons.

Namely, A.I. can almost immediately produce three hundred words on peace with God, but A.I. cannot absolve you.

For that, you need a sinner who knows the Lord Jesus even better than he or she knows your sins.

You need a preacher.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 16, 2024

On the Brink of Heresy

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Romans 1.13-17

When I was a student at the University of Virginia, I befriended the retired theologian Juliann Hartt. One afternoon over glasses of sherry, I confessed to Dr. Hartt a particular sin that burdened me. Because I was a relatively new Christian, Dr. Hartt gospeled me on the sly.

He told me a story.

Taking a few sips of sherry, Dr. Hartt in his North Dakota accent said, “My father, as you know, was a prairie pastor. Well, he had a friend, a colleague I suppose you could say, a Norwegian Lutheran pastor named Johan Aasgaard. One time, at some conference or another, Dr. Aasgaard told my father about a woman who was in his congregation.”

Dr. Hartt took a sip from his short, little glass:

“Dr. Aasgaard had performed this woman’s wedding just a few months earlier. She came to see Dr. Aasgaard one afternoon not long after the wedding.‘Dr. Aasgaard, I have to talk with you,’ she said, shaking and trembling and crying, ‘I must talk to you now.’ So he knew she’d come to confess something to him. And he said to her, ‘There’s a liturgy in the hymnal for someone in your situation.’

He opened the book up to Luther’s service of confession and absolution, and he invited her to kneel there in his office just as he knelt in front of her. “They began working their way through the ritual, and she confessed to her preacher. She told him that before she had been married or even met her husband, she’d had a relationship with a doctor. She’d become pregnant by the doctor, and the doctor, who wanted nothing to do with a child, pressured her and pressured her and pressured her into having an abortion.”

Dr. Hartt stopped and looked at me to make sure I understood.

“Bear in mind, this was in the 1920s. She relented under his pressure and the doctor arranged for a colleague to do it and she had the abortion. “‘That was the end of the relationship with the doctor,’ she confessed to Dr. Aasgaard, crying.”

And Dr. Hartt continued the story:

“When her husband started courting her, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she couldn’t bring herself to tell him. And when the relationship became serious, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she couldn’t bring herself to tell him. And when he proposed to her, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but still she couldn’t tell him. And when they got married, every day she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she could never bear to do it. “‘Now,’ she said to her preacher, ‘every time he touches me all I can think about is what I’ve done and how I’ve betrayed him. And whenever he talks to me, all I can think about is what I’m keeping myself from telling him.’

“When she finished confessing her story,” Dr. Hartt told me, “this pastor stood up and placed his hand on her forehead and said to her, ‘In the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.’ “‘She wept for a long while,’ he told my father,” Dr. Hartt said, “and then she stood up, wiped her eyes dry, and straightened herself up and said, ‘Well now, I guess I better go home now and tell my husband this story.’ “And Dr. Aasgaard looked her straight in the eyes and said, ‘What story?’”

What story?

Of course, the preacher Aasgaard lied— there was no wonderful exchange between the woman's sin and Christ Jesus’s righteousness— if it is not true that the gospel “is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the religious first and also to the irreligious.” Likewise, if the gospel is not the power by which God creates— by speech, by promise— a perfectly right relationship with him, then the sin— my sin— for which Dr. Hartt first told me that story remains on my rap sheet. And I am dead in my trespass.

A little over five hundred years ago, Martin Luther, the founder of the Protestant movement, was a biblical scholar at the University of Wittenberg and an Augustinian monk. He wrote textbooks on the scriptures. He lectured on the scriptures. He prayed the scriptures several times a day.

And he hated God.

Or rather, he hated the God given to him by a church that had lost the gospel.

Late in his life, looking back on his discovery of and conversion to that gospel, Luther credited Paul’s thesis statement in the Epistle to the Romans.

Luther writes:

“I greatly longed to understand Paul’s Epistle to the Romans but nothing stood in the way but that one expression, “the righteousness of God,” because I took it to mean that justice whereby God is just and deals justly in punishing the unjust. My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood every day before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I hated God and murmured against him. Night and day I pondered until I grasped that through gift and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. When I discovered the distinction that the law is one thing and the gospel is another, I broke through.”

The power of God’s gospel as the Spirit led Paul to proclaim it to the church at Rome ignited the Reformation.

By speaking promises, God justifies you.By trusting those promises, God gifts you a right relationship with him.Period— no asterisk, no fine print, no reciprocity required.Again and again, Paul’s Epistle to the Romans has roused the church to passion and freedom.

Two centuries after Luther, John Wesley, the founder of a renewal movement in the Anglican Church, experienced a similar discovery of the power of God’s gospel. The son of a priest, John Wesley was already ordained in the Church of England. He had sailed the Atlantic as a missionary. He had earned a reputation for works of mercy to the poor and exhorting believers to live holy lives. Nevertheless, he had not received and believed the gospel. In his own words, Wesley was an “almost Christian.” Near the end of his Sermon on the Mount, in a passage the lectionary pairs with Paul’s thesis statement, Jesus warns his hearers, “Just because you pray, “Lord, Lord,” does not mean you will enter the kingdom of heaven. Only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven will so enter.”

And the gospel makes God’s will clear and inexorable. God justifies us by speaking promises. Therefore, it is the will of the Lord that you trust those promises.

“Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord,” will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only one who [has faith] will so enter.”

Whereas Luther hated God, Wesley feared him. The Lord who demanded perfect obedience under the law riddled him with anxiety. But then! On May 24, 1738 at a quarter to nine in the evening, John Wesley sat in reluctant attendance at a Bible study on Aldersgate Street where he heard a member read Luther’s Preface to Paul’s Letter to the Romans. And the power of the gospel got him; he broke through.

Wesley writes:

“While Luther was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that He had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.”

Again and again, whenever the church has awakened from its static, slumbering status quo the crater left behind is the explosive apostolic gospel Paul proclaims to the believers in Rome.

Just over a century ago, Karl Barth was a pastor of a little church in a working class village in Switzerland when he learned that all of his former teachers in Germany had signed an official endorsement of the Kaiser’s war effort. Concluding that his liberal theological education was rotten at the root, Barth set out to rediscover the gospel for himself. Barth went to Paul’s Epistle to the Romans where he broke through:

“Paul’s gospel [of Christ apart from works of the law] has stood always on the brink of heresy…And yet, any reader ought seriously to reflect whether this persistent covering up of the dangerous element in Christianity is not to hide its light under a bushel.”

In Paul’s thesis statement, Barth discovered that the one way love of God announced in the gospel is simultaneously a powerful judgement on the “criminal arrogance of religion and all other human projects.”

The “Yes” of the gospel is for the Jew and the Greek exactly because the gospel is first a “No” that is all-encompassing.

God justifies us by speaking promises.We are justified only by God speaking promises.Thus, the gospel’s Yes is also God’s No against all other attempts to accrue righteousness.Though he was not an academic, Barth’s commentary on the Epistle to the Romans “exploded like a bomb on the playground of the theologians.” Just so, Barth’s reclamation of the gospel laid the groundwork for the Confessing Church’s resistance to Nazism during the next world war.

Again and again, God’s gospel in Paul’s letter has freed the church for joyful obedience.

The church’s task of gospeling merely attempts to say what Paul proclaims to the church at Rome, a promise with the power to produce a question like, “What story?”

As the New Testament scholar Frederick Dale Bruner translates the verses:

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for in this news is opened up and poured out a perfectly right relationship from and with the true God and this relationship is received by simple faith.”

Unlike his other letters, the reason Paul writes to the church in Rome is not explicitly stated. While the why of the epistle is unclear, the who is detailed. At the end of chapter sixteen, Paul signs off with his greetings to his readers and the list of addressees surprising. Most of the names Paul names are women’s names, including Junia, whom Paul calls an apostle. In addition to women, several of the names Paul names are slave names. And at least two of the names Paul names are prisoners.

That is—

To people chiefly characterized by weakness and oppression, people who live at the beating heart of the empire that made Mary’s boy Pilate’s victim, Paul writes that the gospel is the dynamis (power, dynamite, TNT) of God invading the world to do what only God can do, speak into existence a right relationship with him that has none of your fingerprints on it.

One way love apart from an iota of anything added by you.This is precisely why Paul must stipulate that the gospel is simultaneously a potential source of shame. The reason the church so often drifts from the gospel is that the gospel is offensive.

As Luther writes:

“The sum and substance of this letter is this: to pull down, to pluck up, and to destroy all wisdom and righteousness of the flesh, no matter how heartily and sincerely they may be practiced.”

In other words, no righteousness that comes from us— not our good deed doing, not the purity of our hearts, and not the zeal of our piety— will endure before God. God’s Yes is also first God’s No. God in his gospel assaults the pious and the pagan alike merely by speaking a promise to which the only response is faith.

To make it plain—

If the message does not elicit questions like:

“Shall we sin the more so that grace may abound?”

“Is the law to no avail?”

“Can I then do nothing?”

If the gospel does not provoke such questions— if the gospel does not bring you to the precipice of heresy, if the gospel does not strike you as “a dangerous element” in Christianity— then it is not the gospel.

Paul has to make explicit that he is not ashamed of the gospel because the gospel is offensive to EVERYONE BUT GOD. The gospel is the great leveler, for everyone who is saved is saved in exactly the same way.The church does not have valedictorians— not even an honor society.

Everyone who is saved is saved in exactly the same way.

Faith.

Alone.

Apart from works.

Which is to say, irrespective of your goodness or your badness.

I remember the time and day and place that I broke through.

It was a Wednesday afternoon in October in 2002. It was a hot Indian summer day and the gathering space for worship at Trenton State Prison felt claustrophobic with humidity. Large outdated fans pushed the thick air around the room and sweat gathered on the top lips of the guards.

Sister Rose led the inmates through the simple liturgy and, as the assistant chaplain, I preached a homily on a passage from 1 Corinthians quite like Paul’s thesis to the Romans. After the service finished, as Sister Rose and I took down the makeshift altar and some of the men stacked chairs, a small inmate with an oily face and long fingernails named Christopher crept up to me. This was his second or third time in worship.

“What you said— what you preached— about how God give Jesus for the forgiveness of our sins,” and then he patted his chest, “I’m here for that.”

Not catching his meaning, I nodded and invited him to come back next week.

“Nah dog,” he said, “I mean, if what you preached is God’s promise— then I believe it. I take him at his word. I have faith.”

I smiled, about to give him a lame attaboy.

But he wasn’t done.

Nor was God done with me.

Quickly, Christopher followed up his profession of faith with an uncomfortable question.

“I have faith. So, that means even after everything I done, I’m right with God?”

I hesitated.

I stalled.

The reason?

In that prison, like many prisons, the inmates who attended the Christian worship service did so because the nature of their crimes was such that church was the only place in the prison outside of their cells where they safe. Most of my congregants at the prison had committed unspeakable assaults upon the most vulnerable population, crimes that— almost to the person— had been perpetrated on them when they were children too.

Christopher was naive enough to think I hadn’t heard him.

“Preacher, I said I believe. I take God at his word. Does that mean I’m right with God?”

To say yes ran counter to every conception of justice and morality I knew.

From behind me, I heard Sister Rose clear her throat and in her Kindergarten teacher’s voice whisper, “If you can’t say yes, Pastor Jason, then you should be attending Mass with me this Sunday.”

I nodded, first to her and then to him.

“Yes,” I said to Christopher, “Yes, you’re justified.”

And Christopher smiled and then exploded in tears, like a chain somewhere within him broke loose.

“That’s crazy!” he laughed with new life.

“No,” I said, “It’s God’s gospel.”

After he’d settled and wiped his eyes, Christopher looked at the two of us and asked if he could confess the sins that no longer condemned him. Sister Rose gestured us to sit at two of the remaining chairs. I sat facing him and we both leaned over to pray and I listened and gritted my teeth as he confessed crimes so ghastly I hope one day I can forget ever having heard them.

When Christopher was done confessing, I put my hand on his head like Sister Rose had taught me. I laid my fingers in between his unkempt corn rows. His head was hot and sweaty and greasy and I felt certain the Lord— or maybe his Enemy— was testing me to see if I’d do the deed and hand over the goods.

“In the name of Jesus Christ…” I began.

He cried again as I absolved him of his sins.

When we were done, he stood up and straightened his khaki uniform.

“Thank you for listening to my story,” he said to me.