Jason Micheli's Blog, page 36

July 28, 2024

We're All Incompatible

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I’m away on vacation in Ecuador this week.

Since the summer’s lectio continua series continues with Romans 5.1-11, here is the last sermon I preached before the shuttered its doors due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The occasion was a clergy gatheri…

July 27, 2024

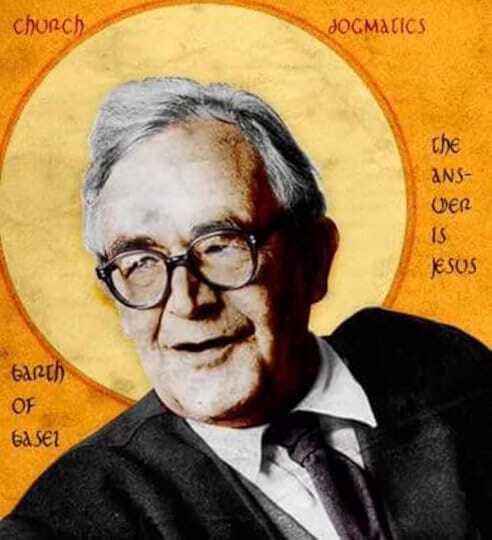

Karl Barth for Dummies

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In light of our Adventures in Barth reading group on Monday nights, here is an old interview with Barth scholar Joseph Mangina.

A professor of theology at Wycliffe College in Toronto, he is the author of Karl Barth: Theologian of Christian Witness as well as a recent theological commentary on the Book of Revelation. He also serves as the editor of the journal Pro Ecclesia.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 26, 2024

Advice to Young Pastors

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

A young pastor recently asked me for advice on preaching in what feels like an uncertain time in the United Methodist Church. Reminder: Jesus promises that hell will not prevail against his church. Christ made so such pledges about the specific United Methodist member of his risen body.

Having been asked, I can think of no better advice than the counsel given by Karl Barth during the theologian’s only visit to America at the end of his career. As noted by his longtime assistant, Eberhard Busch, during his Warfield Lectures at Princeton a student asked Barth:

July 24, 2024

Jesus Christ is the Will of God

Hi Folks,

Here is the prayer by Barth with which we began on Monday:

“Lord our God, when we are afraid, do not permit us to doubt! When we are disappointed, let us not become bitter! When we have fallen, do not leave us lying down! When we have come to the end of our understanding and our powers, do not leave us to die! No, let us then feel your nearness and your love, that you have promised to those whose hearts are humble and broken, and who fear your Word.”

For this coming Monday, we will read up page number 162 in the PDF, which ends with part 3, “The eternal will of God in the election of Jesus Christ is His will to give Himself for the sake of man as created by Him and fallen from Him.”

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadShow NotesSummary

In this conversation, the participants discuss the concept of the eternal will of God in the election of Jesus Christ. They explore the idea that God's will is revealed through Jesus and that the nature of God is love. They emphasize the importance of understanding God's will in light of Jesus and not speculating about it based on personal desires or interpretations. The conversation also touches on the relationship between time, eternity, and God's presence. Overall, the participants highlight the need to ground our understanding of God's will in the person of Jesus Christ. In this conversation, Jason Micheli, Marty Folsom, and Todd Littleton discuss the concept of the hidden God in Luther's theology and Barth's reworking of Calvin's doctrine of election. They explore the idea that God's love is unconditional and that salvation is not just about individual salvation, but about God's election of humanity as a whole. They also emphasize the importance of engaging with tradition while remaining open to critique and reevaluation. The conversation touches on the dangers of misinterpreting theology and using it to justify harmful ideologies. Overall, the discussion highlights the profound mystery and unknowability of God's love and the need for a faithful and humble approach to theology.

Takeaways

God's will is revealed through Jesus Christ and is grounded in love.

We should not speculate about God's will based on personal desires or interpretations.

Understanding God's will requires grounding it in the person of Jesus Christ.

The relationship between time, eternity, and God's presence is complex and mysterious. God's love is unconditional and cannot be earned or lost.

Salvation is not just about individual salvation, but about God's election of humanity as a whole.

Engaging with tradition is important, but it is also necessary to remain open to critique and reevaluation.

Misinterpreting theology can lead to harmful ideologies and actions.

The mystery and unknowability of God's love should be embraced and celebrated.

Sound Bites

"Jesus is the message that the father from eternity is never not sending."

"God is always God, consistently the God who loves in freedom."

"I'm hearing the election of God by his Son and by his Spirit to speak to me."

"If you truly connected with God on the golf course, it would scare the shit out of you."

"The gospel is always yes and yes and yes, and the no has to be seen within the yes and cannot be separated from it."

"God creates heaven as the space or the place to make himself available to his creatures on earth."

July 23, 2024

How Does Faith Make Us Righteous?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber!

In Romans 4, Paul points back to Abraham as the archetype for God’s dealings with all, allowing the apostle to assert, “…to one who without works trusts him who justifies the ungodly, such faith is reckoned as righteousness.” Recalling that righteousness and justification are English translations of the same Greek term, we can ask an obvious if oft-neglected question.

How does faith make us righteous? How does trust justify us apart from obedience of any kind?It is regularly supposed that, on account of Christ, God imputes to sinful believers a righteousness that they do not in fact possess. That is, God calls the ungodly good though they are not so. The Lord credits the fruits of Jesus’s obedient, atoning work to those in whom the Spirit finds faith. Despite what God sees when he looks upon sinners, for Christ’s sake the Father judiciously declares us righteous. As Robert Jenson notes, “Of course what God declares to be so is in fact so; nevertheless, this fact obtains only within the mystery marked by that “despite.”

The challenge inherent to this allegedly tradition answer is that it amounts to God calling wicked good.

Martin Luther’s treatise The Freedom of a Christian is the Protestant Reformer’s response to this question posed by Paul’s epistle; however, in it, Luther does not supply the answers so readily attributed to him.

First, Luther answers the question (How does faith make us righteous?) in a straightforward fashion. Since the gospel is a word that gives us Christ, when we believe the gospel we receive all the salvific gifts that belong to Jesus (righteousness, peace, joy, love, etc).

Still—

How does this work?

How does what belongs to Christ come to be ours as well?

Luther’s first answer to this gospel question brings us back to the law.Namely, Luther reminds us that believing someone is the most straightforward manner to honor them. In the gospel, God promises, “In Christ, by sheer incongruous gift, I am unthwartably determined to make you my own.” Not to trust God’s commitment is to dishonor him.

To trust the Lord’s commitment to rectify us is to honor him and, just so, fulfills the first table of the law.

As Jenson writes:

“As ecumenical theology has always supposed, obeying the second table of the law is the natural result of obeying the first, however slowly or with however many setbacks this may take place. If we trust God, we will seek to fulfill his stated will.”

Just as good works are the fruit of an authentic faith, their absence is evidence that a declaration of faith is a lie. As the catechism teaches children to answer, “We should fear and love God; so that…”

Luther’s second answer to this gospel question directs us to the word of God generally.Simply through audition, the gospel shapes us into righteous persons. Luther appropriates Aristotle’s epistemology but shifts the means of knowing from seeing to hearing. Where Aristotle said that we become what we see, Luther said that we become what we hear. According to Luther, when it comes to my righteousness, what is addressed to me. Or rather, I become more like the one who addresses me in his word.

How does faith make us righteous?

It’s about attention more so than imputation, reading over reckoning.

Faith justifies us in that faith impels us to attend to the word of God.

Summoned to the word by faith, the word communicates to us the good things that belong to Christ. Thus, justification is not a “legal fiction,” as critics sometimes charge. It’s a statement of fact.

As Jenson puts it:

The third step enabled by Luther’s Freedom of a Christian is a theological move.“When God declares those who hearken to the gospel righteous, this is a judgment of faith. When the sinner Jones is grasped by the gospel, “Jones is righteous” is straightforwardly true; the puny sins with which Jones still tries to shape his life cannot stand against God’s righteousness inhabiting him. Justification of the sinner is a mystery but not a paradox or a fiction.”

God’s person and God’s attributes are the selfsame reality.

Therefore, to receive God’s righteousness by hearkening to the word is nothing less than “the ruling presence in the soul of God himself.”

And because the gospel is the word of God in which God gives us Christ, the believer’s soul just is the throne of Christ. Luther made it a slogan of his theology, “In ipsa fide Christus adest: “In such faith, Christ is present.”

Finally, the Reformation slogan (“We are justified by faith apart from works”) makes sense in light of the ruling presence of Christ who inhabits our souls through faithful hearkening to the gospel.

Our righteousness requires no additional works because, by faith, the Righteous One has already taken up residence within us.

We need no good deeds because Jesus has already unpacked his suitcase in our soul.

Our neighbor, however, sure needs them.

(Anselm Kiefer 'Book with Wings')

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 22, 2024

Singing Along with Barth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Here is a recent conversation with Marty Folsom about his latest book, Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics for Everyone, Volume 2---The Doctrine of God: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners and Pros.

About the book:

Show Notes

A Guided Tour of One of the Greatest Theological Works of the Twentieth Century

Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics is considered by many to be the most important theological work of the twentieth century. For many people, reading it and understanding its arguments is a lifelong goal. Its enormous size, at over 12,000 pages (in English translations) and enough print volumes to fill an entire shelf, make reading it a daunting prospect.

Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics for Everyone, Volume 2--The Doctrine of God helps bridge the gap for Karl Barth readers from beginners to professionals by offering an introduction to Barth's theology and thought like no other. User-friendly and creative, this guide helps readers get the gist, significance, and relevance of what Barth intended for the church... to restore the focus of theology and revitalize the practices of the church.

Summary

In this conversation, Marty Folsom discusses his new book on volume two of Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics. He explains how Barth's theology emphasizes the importance of a dynamic relationship with God, where God speaks and invites us to respond. Folsom uses the metaphor of music to convey the idea of participating in this relationship and invites readers to sing along with Barth's theology. He also explores Barth's rejection of natural theology and his critique of the Nazi co-optation of Christianity. Folsom highlights the significance of community and conversation partners in engaging with Barth's work. The conversation explores the themes of the holistic nature of theology, the relevance of Karl Barth's dogmatics in everyday life, and the style and purpose of Barth's writing. It emphasizes the importance of understanding theology as a relational and transformative endeavor that involves active participation and dialogue. The conversation also touches on the themes of hospitality, playfulness, and the journey of restoration. The guests discuss the emotional impact of theological concepts and the moments that have moved them to tears.

Takeaways

Barth's theology emphasizes the importance of a dynamic relationship with God, where God speaks and invites us to respond.

The metaphor of music is used to convey the idea of participating in this relationship and singing along with Barth's theology.

Barth rejects natural theology, which seeks to understand God through human wisdom and inclinations, and instead emphasizes the need to understand God on God's own terms.

Barth critiques the Nazi co-optation of Christianity and emphasizes the importance of understanding God's character and intentions before engaging in other theological discussions.

Community and conversation partners are essential for engaging with Barth's work and deepening our understanding of theology. Theology should be understood as a holistic and relational endeavor that encompasses all aspects of life.

Karl Barth's dogmatics have relevance and implications for everyday life, including professions, relationships, and societal structures.

The style of Barth's writing, characterized by repetition, metaphor, and musicality, is intended to engage readers emotionally and invite them into a transformative encounter with God.

Hospitality, playfulness, and the journey of restoration are key themes in Barth's theology.

Theological concepts can have a profound emotional impact and move individuals to tears.

Sound Bites

"The nature of what makes relationships work is that we recognize that as persons, we need the other person to be in dialogue with us."

"God's work in our lives sets us free to live in a particular way, trusting in His promises."

"The nature of music is to invite the reader to sing. It allows for creativity and a dynamic relationship with God."

"We have lost our curiosity for the implications of what a world looks like that has been arranged so that a loving, caring concern for one another, originated from God, is able to work itself out in every aspect of human being, through the arts, through the sciences."

"There is no arena of life that is outside of the implications of what Karl Barth invites us into."

"We're each valued for the dynamics we bring and our disciplines don't give us value. It's who we are in Christ."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 21, 2024

Justification By Unbelief Alone

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward! Become a paid subscriber!

Romans 4.1-5, 13, 16, 17-25

Over twenty years ago, I was part of a captive audience for an introductory class on homiletics. The only thing worse than being subjected to novice preachers is being forced to listen to novice preachers who think they’re great preachers. One afternoon this belligerently confident, hyper-evangelical classmate preached his “sample sermon” before the homiletics class. He took as his scripture text the Lord’s first promise to Abram:

“Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing.”

For twenty minutes my classmate preached about Abram’s leap of faith, leaving his home in Haran as an elderly man to venture out to the land the Lord had yet to disclose to him.

The rookie preacher’s sermon was frenetic.

His delivery was demonstrative.

His zeal for the Lord was palpable.

And his urgency for us to share it was lined across his face.

He clearly thought he was the superior preacher to all of us and, admittedly, his affect was effective. However, a few minutes into the sermon, I noticed the smooth, bald head of our homiletics professor, Dr. James Kay, had turned a crimson red. A few minutes later, Dr. Kay looked restless and irritated. A couple of moments more and Dr. Kay, an amateur boxer, appeared as though he wanted to clock the preacher hard enough for an eight count.

Once the sermon was finally over I saw that what I had taken to be Dr. Kay’s exasperation was in fact righteous indignation. Needless to say, it was not the reaction the beaming student preacher had anticipated.

“Do you realize,” Dr. Kay thundered, “not one of your sentences had God as the subject?!”

The point seemed lost on the preacher.

“God was not the subject of any of the verbs in your sermon,” he explained.

Blushing, the preacher remained confused.

“Abraham is not the primary protagonist in the story of Abraham anymore than you are the primary protagonist in the story you call You. God IS. You turned a word about God into a lesson about us. IT’S ABOUT GOD!”

It was a mic drop moment before mic drops were memes.

“So, what shall we say that Abraham our forefather learned? For if Abraham was justified on the basis of his works, he then has a basis for boasting. But so far as God is concerned, that is not the way it happened. For what does scripture say? Abraham believed God and that was regarded as righteousness.”

Imagine that you are in a bookstore, perusing the shelves, and you come upon a new biography of another Abraham, Abraham Lincoln. Intrigued, you pull the biography from the shelf and start to read it. What you discover inside surprises you. The biography repeatedly describes Lincoln as the first Republican president, the inaugurator of a line of Republican leaders running to the present day. Yet the same biography never once mentions Lincoln’s debates with Stephen Douglas, his leadership of the Union during the Civil War, or his issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. On the basis of what the biographer omits, you would certainly suspect the author was up to something strange.

Likewise, in turning to the story of Abraham the apostle Paul excludes the very items about Abraham for which Israel celebrated him.

Paul repeatedly points to Abraham’s trust in God.

But Paul never once mentions Abraham’s obedience.

Here in his epistle, Paul has just signaled the gospel with his big, “But now!” The grave, by grace, is not the end. Somehow, Paul proclaims, at the site of sin there is a redemption that reveals and a grace that gives righteousness. This gospel not only entails reconceiving the possible but also rereading the past. To his astonishment, Paul discovers that “pages from the past are proclamations of the gospel.”

Specifically, Paul zeroes in on a single verse, “Abraham trusted God and that was regarded as righteousness.” Notably, Abraham’s faith justified him three decades before Abraham and his household received the sign of covenant membership, circumcision. As Frederick Dale Bruner notes, the apostle “loved this calendric and cosmic fact.”

This is not to suggest the Bible is silent on the matter of Abraham’s works.

The Book of Genesis narrates Abraham’s obedient migration from Haran.

The Book of Genesis narrates Abraham’s obedient circumcision of himself and his household.

The Book of Genesis narrates Abraham’s obedient binding of his son, Issac.

But none of these acts of obedience make Abraham righteous before God.

The rabbis regarded Abraham as the chief example of righteousness, and they took Abraham’s righteousness to be rooted in his obedient works. For example, the Book of Sirach praises Abraham for keeping the law and remaining obedient to God when tested. The Book of Jubilees extols Abraham for exhorting others to obey all of God’s commands. Even the New Testament books of James, Hebrews, and Acts praise Abraham for his actions obeying God’s commands. But none of these acts of obedience are what scripture identifies as the basis for God justifying Abraham.

Indeed, at the moment God calls him and for three decades more, uncircumcised Abraham simply is the ungodly.Nevertheless, the Logos encounters Abraham.

The Lord brings him outside.

And Christ promises him, “Look at the sky. Number the stars— if you’re able to count them. So shall your offspring be.”

I’m going to have a whole world through you.

Despite their advanced age and the patent absurdity of the promise, Abraham trusted God to perform the impossible. And so trusting, God regarded Abraham as righteous.From the surprising and incongruous place of cross and resurrection, Paul now sees an order to Abraham’s story hitherto overlooked.

Abraham believed God before Abraham obeyed God.

Abraham trusted God’s promise before Abraham followed God’s command.

Abraham relied upon God to realize this promised future before he stepped out towards it himself.

Abraham’s belief came before his obedience.

But even more importantly, back before Abraham’s belief is the unthwartable will of God which manifests in his gracious promise to Abraham.Put differently:

God’s determination to have a world preceded God’s promise to Abraham.

God’s promise to Abraham preceded Abraham’s faith in God.

Abraham’s trust in God’s power to perform the impossible empowered Abraham's obedience.

It all starts with God. It’s all contingent upon God.Abraham’s faith would be delusion had not God first encountered him with impossible promises and then performed them.

By repeatedly pointing to Abraham’s faith in God, Paul in fact points to Abraham’s God.

Thus, by repeatedly pointing to Abraham’s faith in God, Paul in fact points to Abraham’s God. That is to say, the primary protagonist in the story of Abraham is not Abraham; Abraham is the object of God’s gracious will and rectifying work.

“So, what shall we say that Abraham our forefather learned?” the apostle asks his audience before answering his own question. Abraham discovered that the God who raised Jesus from the dead is and ever has been and always will be the one who, by grace, promises to perform the impossible so determined is he not to be God without us.

A friend of mine teaches a class at Duke Divinity School in which the first assignment every year is for the students to write an essay describing how the risen Christ is the only explanation for why they are enrolled in seminary. After he read one student’s submission, he called me up and said to me:

“Jason— you’ve got to meet this guy. His name is Slice Penny if you can believe it. You’ve got to meet him. It’s damn hard to deny the living God when Jesus leaves as many fingerprints as he has on Slice.”

Slice grew up on third base in Charlotte, North Carolina with a silver spoon in his mouth. His teenage years were such that after high school he went as far away as he could for college in order to rebrand himself, putting the drugs and the booze in the rearview mirror.

“So I went to Florida State,” he told me one afternoon a few months ago, “And, you know, I had this realization. As soon as I got out of my parents's car, I looked down and I saw my shadow, and I had an eerie feeling because it was like, no matter where I went, there I was.”

To tamp down the darkness within him, Slice lost himself in busyness. By the time he ascended to the Inter-fraternity Council’s presidency he was not only drinking too much and doing cocaine, he was dealing drugs for a cartel, extorting fraternity presidents to coerce their brothers into buying drugs exclusively from him.

“I always had an entrepreneurial spirit about me,” Slice told me, “When I knew I was in over my head, I went to to my drug dealer's house and there was a frighteningly massive amount of drugs there. I said, “Thanks for this wonderful opportunity, but I think our business partnership has run its course.” He laughed at me and threw a huge duffel bag at me and said, “I'll see you in two days.” Feeling trapped, alcohol became my master.”

Slice then told me how he went home to North Carolina to dry out. He made it two days with no drinking or drugs. On the third day, he was standing in his parents’s backyard by the swimming pool when he went into alcohol withdrawal.

“I was standing in my parents backyard, saying, “I gotta go back to school. I gotta go back to school.” And my whole body locked up and I fell into the swimming pool, sank to the bottom.”

Slice told me that his Mom saw him convulsing on the bottom of the pool.

So she jumped in after him.

“I don't remember any of this,” he said to me, “but she told me my body was convulsing so hard she couldn't get a grip and I was too heavy to lift up. And she told me that every time she came up for air, she would scream, “Jesus, help me!”

Slice was on the bottom for two minutes. When his mom finally brought him up, she was convinced she was holding her dead son. When she came up with him from the bottom, she saw two sets of feet on the deck of her pool. They belonged to two guys who just happened to cut their golf game short at the nine hole because their wives had complained that morning that they spent too much time on the course.

The nine hole is the one behind Slice’s house.

They heard his mother scream for Jesus.

They rushed to her.

They pulled him from the pool.

His lips were blue.

One started CPR while the other called the rescue squad.

A day after Slice was released from the hospital, DEA agents knocked on his parents’s front door to arrest him for drug trafficking.

“My mom fell to the ground crying,” he told me, “And in that moment, there was this strange dichotomous sensation. “My God, my life is over. But also thank you, God.”

Upon conviction, a clerical error labeled Slice as an illegal alien so he got sent to the deadliest maximum security prison in Florida.

“I felt like a house cat thrown in the jungle with lions,” Slice told me, “I got to that prison and I prayed, “God do what you promise to do, and help me to trust and believe you will.” The next day I met Ricky Goldsmith, in for twenty-four years for murder, who preaches every Sunday. The next night I prayed, “God, why did you bring me here?” And I heard God say to me, “I brought you here so Ricky could get right.” You know, you'd never guess it, but it was in prison that God really rectified my life, changed my heart, put me right. It was a double serving of humble pie. And it wasn't sweet to eat, but it's been nourishing.”

Like Job before the Whirlwind, his testimony left me mute.

Slice looked up at me and he said, “I look back at my life. And I used to think, “Why did I do what I did? How am I alive? Where am I headed?” But now I can see this is the story God was writing for me all along.”

“…someone who trusts the One who justifies the ungodly, that person’s faith is regarded as righteousness.”

The conclusion of Romans 3 is quite “possibly the most important paragraph ever written” and Abraham is its corroborating witness.

Not only, these chapters of Paul’s epistle supplied the source material for the slogan of the Protestant Reformation, “We are justified by faith apart from works.”The slogan is not the gospel but it is the rule for speaking gospel. The problem with the slogan, however, is that very often the church presents it as the polar opposite of what Paul intended, which is to say faith— belief— becomes but another work. Just so, we imagine:

“There is a list of things which God really wishes we would do— be kind to animals, be generous to the poor, be against war and injustice; that on the list is “believe in God” and that, as a favor to Jesus, God has decided to let us off the rest of the list if we will do just this one.”

This is the precise opposite of what Paul and, with him, the Reformers seek to say. As Robert Jenson writes, to offer salvation conditional on your belief (If you have faith, then God will justify you) “peddles grace more cheaply than did the worst medieval indulgence sellers.”

To offer salvation conditional on your belief “peddles grace more cheaply than did the worst medieval indulgence sellers.”

The apostle Paul’s epiphany, the whole point of the Reformation, was that the gospel promise is every bit as unconditional as God’s promise to Abraham is inviolable. Jenson argues that the language Paul uses in this passage— faith and justification and righteousness— are now so heard in contradiction to their original intent that we should eliminate the terms altogether. But, seeing that we cannot jettison them, Jenson argues we should deploy them in a subversive manner that recaptures the shock of Paul’s intent.

“To use a drastic example,” Jenson writes, ““justification by unbelief alone” could be, now, the only way to make the Reformation point with this language.”I’m going to have a whole world through you.

God is the subject of the sentence called gospel. God is the primary protagonist of the salvation story. This becomes clear when you see that the Reformation slogan (“We are justified by faith apart from works”) is merely the doctrine of election stated with respect to us. The doctrine of justification uses passive voice sentences while the doctrine of election uses active voice sentences. But they both make the same claim.

To say that we are regarded righteous by faith and not by works, passive voice, is exactly to say in the active voice, “In Christ, by sheer incongruous gift, God is unthwartably determined to make you his own.Not to trust his commitment is to dishonor him.

To trust his commitment is to honor him and, just so, fulfills the first table of the law, making you righteous.”

This just is the claim in God’s proper name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

God is the God who determined himself to be for us and with us before there was a single one of us. God did not create the universe for the sake of creating it. God created the universe in order to rescue sinners and live in loving fellowship with them. As Robert Jenson summarizes Karl Barth’s doctrine of election:

“In his eternal decree, God decides to love the creature; therefore, God decides to create the creature…The act of creation is the carrying out of God’s decision before all time, his decision to love sinners. The creation exists as the necessary apparatus for the reconciliation of sinners.”

All of history is the unfolding of this eternal decision.

This is why when Paul affirms Abraham’s faith in verses seventeen to twenty-two, Paul does not focus on Abraham believing the content of the promise. Instead Paul highlights how Abraham faith’s is that which witnesses God’s actions in the world, “giving life to the dead and calling into existence the things that do not exist.”

Faith is that which witnesses God’s actions in the world, “giving life to the dead and calling into existence the things that do not exist.”

The Reformation slogan is not an explanation for how you get saved. The Reformation slogan is the announcement that God is determined to save you. It is not as though your future hangs in the balance, contingent on your belief or unbelief. You exist for no other reason than to be loved by God. To “glorify God and enjoy him forever” is your destiny. And God is determined to leave as many fingerprints on you as necessary to get you there.

“So how did you end up at Duke Divinity School?” I asked Slice.

He smiled and said, “My first Sunday home at the church, Bishop Leland was in worship. The church gave me a Bible and asked if I had any testimony to share. I don't remember what I said. I remember feeling the Holy Spirit on me. Afterwards, Bishop Leland asked me in front of everybody, “Is God calling you?”

“Then what?”

“A little while later,” he said, “I was working and trying to finish my degree when the district superintendent called me. He said, “I’ve got this church way out in rural North Carolina that needs a pastor, and they tell me that what they really want is a twenty-six year old recovering drug addict and alcoholic who’s just come home from prison for drug trafficking, still living at home with his parents, and taking classes at the community college. You sound just perfect for them.”

I laughed.

“So I took the call,” Slice told me, “And it’s like God created a whole new life out of nothing. Not long after, I got a scholarship to Duke. I cry walking to class just about every day because someone like me has no business in such a place. The only explanation is God.”

“Hoping against hope…Abraham believed the God who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist.”

Dr. Kay had just thundered his mic drop moment in our homiletics class.

The day’s preacher nodded sheepishly while we all jotted down the professor’s point. Then Dr. Kay surveyed the classroom like we were all sitting ringside and paying attention to the final blow.

“The claim in your scripture text is not “We are all on a faith journey to God.” The claim in your scripture text is that “The author of our salvation is God.”

And then he wrote the claim on the white board, “The author of our salvation is God.” Capping the marker, he turned to us and said, “Preachers, diagram your sentences. If God is merely the object of the sentences you speak— if God is not the subject of sentences— then you are not proclaiming the God who justifies the ungodly.”

Robert Jenson writes:

“It is important to see the size of the assertion Paul makes here. The choice of a breakfast cereal— and the movements of Communist armies— all take place solely insofar as they serve the movement of the special history of grace…if it were not for a hidden connection with God’s plan to reconcile sinners, these events would not take place.”

Which is to say—

I am not the one who, in a moment, will say to you, “Come to the table.”

God is your destiny.

The author of salvation is God.

In the End, your life— all of it, every bit of it, each difficult and beautiful part of it— just is the love story of how God finally won you to himself.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 20, 2024

The Gospel is a Promise whose Speaker is Good on his Word.

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

My friend Ken Sundet Jones is covering the pulpit for my other friend, Sarah Hinlicky Wilson, this summer for the Lutheran congregation in Tokyo. Here is his first sermon for them.

And if you haven’t already, check out the Iowa Preachers Project on which Ken and I are collaborating.

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

Reading the Bible is often difficult. Sometimes it happens because the story it tells is so challenging. Sometimes the difficulty happens because there is such a huge chasm dividing the ancient world of the Old and New Testaments from ours, and we don’t catch nuances that any first century reader would understand. Much more rarely the difficulty happens because we simply don’t understand the words. We don’t recognize our master's voice when we hear it.

That’s what happened when, at the end of the nineteenth century, European missionaries in Papua New Guinea worked to translate the Bible into Tok Pisin, or what many people call “Pidgin English.”

Today’s Gospel reading posed a real hurdle. The people the missionaries hoped to bring God’s word to had no idea what a sheep was, let alone what a shepherd was.

So the translators had to find a solution. They began with the word “master” to describe the person who owns the sheep. Then they had to deal with the fact that Tok Pisin doesn’t have an “apostrophe-S” like in English, or a word like “watashi” in Japanese to indicate ownership. So they used the word “belong.”

The word they landed on for a sheep was “sip,” but Tok Pisin makes things plural by doubling a word to show that there’s more than one. In the end a single word in English or biblical Greek, became four words in Tok Pisin: “master belong sip-sip.” All of which shows how ingenious and committed those translators were, but it offers no help for readers of John 10 who have never seen a sheep, much less handled one, felt its wool, or smelled its awful odor before the wool is cut off, cleaned, and spun into yarn.

When preaching on a passage like this one, preachers in Papua New Guinea often will talk about a person who cares for hogs instead of a master belong sip-sip.

All of this is to say that for me to preach on this passage of God’s Word is an easy thing among the people I grew up with in the American west where sheep and cattle ranching are well known and understood. But where I live now, in a city of a half million people, people don’t know about sheep, and certainly here in this giant city, most people have no personal experience of a sheep except in petting zoos or the Shaun the Sheep exhibition here in Tokyo several years ago.

So here’s what you need to know about Jesus, our Good Shepherd who looks after us, his sheep: If Jesus calls you his sheep, it’s not a compliment. Newborn baby lambs are cute, trying to stand up on wobbly little legs and bawling for their mothers. But you don’t want to be in a pen with even a few of them. The noise is loud and relentless.

And as soon as the lambs’ mothers no longer let them suckle, they lose their cuteness and become what every shepherd knows them to be: stupid, thoughtless creatures whose sole motivation is eating whatever they find wherever their noses lead them. Sheep are in constant danger. If it weren’t for shepherds, many fewer of them would survive and no rancher would have a return on his investment.

On top of everything else, in Jesus’ time shepherds weren’t regarded with any honor. Only a fool would want to work tending such hopeless creatures. Shepherds, including the ones in the Christmas story to whom the angels announced Jesus’ birth, were outsiders, widely regarded as drinkers, and certainly not people you’d want your daughter dating. Sheep-herding was a job on the lower levels of society.

So Jesus calling himself the Good Shepherds tells us something about both us and our Lord. First, the story implies that we can’t manage life on our own. It’s our sinful nature to go our own way, to let our bellies and other desires guide our decisions. Often, like sheep, we don’t even think. We need a shepherd to protect us from the wolves that prowl around us, seeking to devour us. But even more we need the shepherd to save us from ourselves.

Second, if Jesus is the Good Shepherd, it means we have a God who is willing to come to us not in power or prestige. We have instead a God who emptied himself for our sake, to the point of being regarded as an ungodly blasphemer, and being branded as a dangerous criminal, tortured by the Roman authorities, and executed on a cross.

Jesus the Good Shepherd humbles himself and gives his life because of your sinful foolishness and for your benefit because he is just that: the Good Shepherd. He’s no normal shepherd.

He’s the good one who doesn’t abandon his flock, who will search out even a single lost lamb, who has decided a sheep like you is worth living and dying for.

If we don’t know anything about sheep and shepherding, we do know about feeling lost, about losing our way, about finding ourselves in difficult predicaments, and about being on the verge of death. To these things our Lord says, “I have found you, and I will carry you home to a safe pasture in my arms.” This is a promise whose speaker is good on his word.

Jesus even now has laid you across his shoulders. He who carried his own cross to Golgotha has no problem with your weight being laid on him. Because of his promise to you, you belong in his flock, and he has a place reserved for you in his pen. He says his sheep know his voice. He’s calling your name today. Do you recognize your Good Shepherd? Do you know that with this food at this table today, in the Lord’s Supper, he’s ready to give everything he has to you so that you might know his mercy and goodness?

Your Lord Jesus lays his claim on you. And he does so by saying your name. And not once. And not twice either. But over and over, all the way from eternity. And he won’t stop either. Not until your last day. And then, like he did with Mary Magdalene in the garden at his resurrection, he will say your name one final time, and you will recognize your shepherd by the sound of his voice calling your name (no translators needed) And you will rise. You will rise.

Rise, rise. Rise to eternal life. Amen.

And now May the peace which far surpasses all human and sheeply understanding keep your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus our Lord. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 19, 2024

The Gospel Always Comes Before the Law

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

This summer I’m preaching a lectio continua series through Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. A major component of Paul’s argument concerns the relationship between God’s two words law and the gospel, or command and promise. That is, if the gospel announces “Done, for you!” then how are believers to understand the law which exhorts, “Do?”

Consider the law Jesus lays down in his Sermon on the Mount.

Is Jesus a New Moses?

Or, is Jesus the Faithful Israelite who perfectly obeys the law for the rest of us who cannot?

Karl Barth wrestles with the relationship between the law and the gospel in volume II.2 of his Church Dogmatics, saying:

“The doctrine of the divine election of grace is the first element, and the doctrine of the divine command is the second.”

By prioritizing election (God’s choosing of humanity in Christ) over command, Barth famously inverts Luther’s distinction between God’s two words in what becomes his gospel-law thesis.

Because of his experience watching the German Church incapable of maintaining its Christian distinctiveness during the world wars, Barth was wary of permitting human experience to be the starting point or the interpretative lens into revelation. Barth believed Luther’s distinction between the law and the gospel did just this, privileging the subjective experience of the individual when confronted by the accusing demand of the law and the gospel promise of its fulfillment for you.

Instead Barth reversed the ordering of law and gospel, prioritizing the electing God whose decision to save us from sin precedes creation itself.Barth believed Luther’s distinction between the law and the gospel privileged the subjective experience of the individual rather than God’s eternal decision not to be God without us.

The Word that is Jesus Christ is prior to God speaking creation into being; therefore, the gospel always comes before any demand of obedience from God to God’s creatures. Not only is the gospel prior to the law for Barth, the two are one inseparable word, for the giver of the Sermon on the Mount is the word who was with God, who is God, and through whom all things were made.

Just so—The finger who inscribed the law on tablets of stone belonged to a nail-scarred hand. The Logos is Israel’s lawgiver.To begin with the gospel means to begin with the doctrine of election: “The doctrine of election is,” according to Barth, “the sum of the gospel.” In election, God wills to be for humanity and for humanity to be with God as his covenant partner. Election makes a claim on the one elected in the form of the law.

As David Hunsicker writes in The Making of Stanley Hauerwas:

“The problem, for Barth is that Lutheran theology overdetermines the difference between law and gospel in a manner that results in the eventual emancipation of ethics from dogmatics.

Barth’s insistence that the gospel and the law are the one inseparable word from the Word is a self-conscious determination to keep dogmatics and ethics together. Barth is concerned that establishing the law as a separate word of God apart from Jesus Christ means that you can have competing claims to what the word of God commands— one based in universal laws and represented by worldly ordinances such as civil magistrates and the other based on God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ.

A law independent of the gospel and an ethics independent of dogmatics threatens the freedom of the gospel itself, leaving us subject to “the worldly ‘ordinances’” and “the ‘competence of experts.’”

This was what Barth and the Confessing Church movement had specifically rejected eight years prior at Barmen:

“Jesus Christ, as he is attested to us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God which we have to hear, and which we have to trust and obey in life and in death. We reject the false doctrine, as though the church could and would have to acknowledge as a source of its proclamation, apart from and besides this one Word of God, still other events and powers, figures and truths, as God’s revelation.”

Says Hunsicker:

“Luther sows the seeds for what will be eventually known as “the introspective conscience of the West.”The second use of the law, as Lutherans would later call it, acts as a judgment on all our sinful doing and leads us to the truth of the gospel, that is, that our being is determined by our passive (nondoing) reception of God’s grace. Human action becomes obsolete with regard to the question of human being. In this regard, personhood is now reconstituted along the lines of a sort of “inside-out” Cartesian dualism.

In contrast, Barth’s insistence that the law and the gospel are the one inseparable word of God registers as a strong protest against inside-out dualism. For Barth, the person is constituted as a being-in-becoming, or a being-in-action. Barth’s actualistic ontology means that human being is self- determined by human doing as it corresponds to divine action. God acts toward humanity in the gospel. Then, in a corresponding action, humans act in receiving the good news and responding with obedience to the law.

The result is twofold.

First, humans are given a real agency with regard to the gospel. Obedience to the law does not lead to God’s grace, but it does arise as a genuine human response of gratitude to God’s grace.

Thus Barth’s refusal to separate law from gospel grounds his claim that ethics cannot be independent from dogmatics. This move immediately affects questions related to Christian social witness and divine and human agency. For Barth, both sorts of questions must begin with the subject of Christian dogmatics, the covenantal God who determines to be for humanity and who elects humanity to be with him.

Barth’s refusal to separate law from gospel grounds his claim that ethics cannot be independent from dogmatics.

This brings us to the two remaining components to Barth’s gospel-law thesis:The priority of the gospel to the law

And the law as the form of the gospel.

Both components differentiate the gospel from the law in the larger context of the unity they share as the one word of God.

To say that the gospel is prior to the law is to affirm that “the very fact that God speaks to us, that there is a word of God, is grace.”

“The very fact that God speaks to us, that there is a word of God, is grace.”

In other words, to place the gospel before the law is to say that humans always encounter the word of God in the context of the covenant of grace.

Even when the one word of God is law, it is law as the form of the gospel. That is to say, the law always confronts us from the perspective of what has been accomplished by Jesus Christ on our behalf. In this respect, the already-fulfilled law does not hang from our necks like a millstone. Unlike Luther’s second use of the law, it does not accuse us or drive us to repentance; instead, it demands that we “allow [Jesus’] fulfillment of the law . . . to count as our own.”

Jesus’ fulfillment of the law, however, does not mean that Barth forecloses on human agency. To the contrary, the reversal of law and gospel “is at heart motivated by a desire to register a place for human agency.” Above I noted that a law which is separate from the gospel as a second word of God risks appeals to competing sources of divine revelation. Similarly, a law that precedes the gospel always threatens to become an independent law (e.g., natural law) that points to an idol instead of the true God.

The law that is rejected is the law that suggests “we must do ‘something’ to make the gospel apply to us.” The law that is affirmed is the law that expects humans to do something on account of the fact that the gospel already applies to us.This is how Barth’s reworking of the law as the form of the gospel avoids Luther’s original concern, works righteousness.

Luther’s solution is to suggest that humans are utterly passive; humans do nothing, God does everything. For Barth, this solution is problematic,“What is wrong about works righteousness is not the fact that the human does something, so that in her passivity she would be in concordance with the grace of God. The wrong thing is that human action stands in contradiction to grace, competes with it rather than conforms to it.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 18, 2024

Radical Sanctification

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber!

I am excited by the feedback I’ve received from some of you listening, viewing, and reading along with us.

If you’d like to join us on Mondays at 7:00 EST, the link is always THIS.

And here is the PDF of Barth’s Church Dogmatics: II.2.

We will start section 2 of §33 on Monday, up to around page 150 in the PDF:

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadShow NotesSummary

In this conversation, Jason Micheli and Marty Folsom discuss the concept of election in relation to Jesus Christ. They explore the role of Satan in the divine drama and how he helps make sense of redemption. They also discuss the inversion of Luther's distinction between law and gospel, with Bart emphasizing that the gospel comes first and the law is the outworking of living according to the gospel. They address the apparent contradiction between God's will for all to be saved and human freedom to reject salvation. They also touch on the idea of radical sanctification and the permanence of God's promise in the face of human sinfulness. In this conversation, Marty Folsom and Jason Micheli discuss the concepts of sin, sanctification, and being in Christ. They explore the idea that humans are both completely sinners and completely saints, living in the tension of both. They also delve into the concept of headship, with Jesus Christ as the electing God and the elected man who is the source of life for the church. They discuss the depth of being in Christ and the interpenetration of lives. They also touch on the topics of God's providence, predestination, and grace.

Takeaways

The concept of election in relation to Jesus Christ is explored, highlighting the role of Satan in the divine drama and the idea of redemption.

Bart inverts Luther's distinction between law and gospel, emphasizing that the gospel comes first and the law is the outworking of living according to the gospel.

The apparent contradiction between God's will for all to be saved and human freedom to reject salvation is discussed, emphasizing the permanence of God's promise.

The concept of radical sanctification is explored, highlighting that it is God's work in restoring humanity to their true family of origin.

The conversation also touches on the honesty of the Old Testament in addressing human sinfulness and the need for Christians to be honest about their own transgressions. Humans are both completely sinners and completely saints, living in the tension of both.

Jesus Christ is the electing God and the elected man, and He is the source of life for the church.

Being in Christ brings depth and interpenetration of lives.

God's providence accompanies all of creation at every moment, providing for its existence and sustaining it.

Predestination is not about God arranging eternal salvation or damnation, but about God's intentional and loving presence in all of creation.

Grace is not an abstract concept, but the personal presence of Jesus, who loves us despite our failures.

Sound Bites

"The nature of sin and evil and Satan lives within that world that is only there because God loves and God loves in freedom."

"The only way that we can affirm the reality of Satan and evil is because Jesus deals with it."

"Radical sanctification is God turning us towards himself."

"What's at stake and keeping it personal is, is"

"What does unpack what that phrase means?"

"The more times you can do that, the more there is a sense of depth"

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers