Jason Micheli's Blog, page 38

July 5, 2024

Luther and the Gospel

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber!

Hi Friends,

You may have noticed that I’ve recently begun a lectio continua sermon series through Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. Returning to Paul’s letters, I recalled that the Minion and I had offered an online class on Luther and the …

July 3, 2024

Grace is in the Triune Name

Hi Friends,

I am excited by the feedback I’ve received from some of you listening, viewing, and reading along with us.

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadShow Notes

If you’d like to join us on Mondays at 7:00 EST, the link is always THIS.

And here is the PDF of Barth’s Church Dogmatics: II.2.

Note, for the next session we will read to page 127.

Summary

The conversation explores the themes of Jesus Christ, election, and the work of Karl Barth, specifically dogmatics, volume two. The discussion touches on the idea of God messing with time and the song 'Forever Now' by the Avett Brothers. The conversation then delves into the Greek view of the Atonement and the different theories surrounding it. The main focus is on Karl Barth's understanding of the Atonement as the yes of God before any discussion of what is atoned for. The conversation also addresses the prevalence of Pelagianism in the Protestant church and the importance of joyful obedience.

In this conversation, the hosts discuss the concept of election and its connection to Christmas. They explore how election is not a reaction to something, but rather the self-determined identity of God. They emphasize the importance of starting with God and the Word in preaching, rather than focusing on the human situation. The hosts share personal stories of loss and find comfort in the belief that their loved ones are in the arms of Jesus. They highlight the need for the church to offer more than just superficial comfort and to ground its message in the love of God. The conversation ends with a prayer by Karl Barth.

Takeaways

God's love and grace are central to the Atonement

The Atonement is not a transactional process but a reflection of God's love for humanity

Pelagianism emphasizes human effort in salvation, while Barth emphasizes God's grace

Joyful obedience is a response to God's love and grace Election is the self-determined identity of God and is not a reaction to something.

Preaching should start with God and the Word, rather than focusing on the human situation.

The church should offer more than superficial comfort and ground its message in the love of God.

Believing that loved ones are in the arms of Jesus can bring comfort and energize one's faith.

The concept of election is connected to the Christmas story and the proclamation of the love of God.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 2, 2024

The Sin of Scripture Reading

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber!

I recently attended a worship service in which the assigned scripture was read in an unctuous, dramatic fashion by a lector who was not visibly present at the altar. Perhaps he had been recorded ahead of time and it was merely played through the sound system. If it was not an incarnate event, then it was even more dreadful.

The experience called to mind Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s instructions for reading scripture in worship. My friend and mentor Fleming Rutledge frequently points preachers back to Bonhoeffer’s guidance in Life Together; in fact, Bonhoeffer stipulates that preachers are often the worst readers during the liturgy.

Bonhoeffer’s instructions for public Bible reading comes in the context of pastoral concern for those enduring the anguish of Anfechtung, Luther’s term for despair. “How are we supposed to help rightly other Christians,” Bonhoeffer asks, “who are experiencing troubles and temptation (Anfechtung)?” Clearly, he notes that the believing community has no other and no better medicine to dispense than God’s own Word. In the face of despair, all our words fail for we cannot promise what only God can unconditionally promise, the future. As Paul Zahl says often, preachers should proceed on the assumption that their hearers have crawled over glass to get there for a word from the Lord. Given the stakes, we have something more important to do than perform.

Given the stakes, we have something more important to do than perform.

Bonhoeffer likens Christians to the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old (Matt. 13:52). Just as the master does, Christians can speak “out of the abundance of God’s Word the wealth of instructions, admonitions, and comforting words from the Scriptures.” If the gospel is God’s invasive power in a world under the Power of Sin, then God’s Word itself is the Lord’s weapon with which we will be able “to drive out demons and help one another.”

Thus the question of how to read the scriptures rightly in worship is a question about how to handle best the TNT the Lord has given us. For Bonhoeffer, it’s a matter of how to dispense properly the medicine God has entrusted to us.

The pastoral concern then leads Bonhoeffer to ask, “How should we read the Holy Scriptures?”Bonhoeffer proffers these instructions:

“In a community living together it is best that its various members assume the task of consecutive reading by taking turns. When this is done, the community will see that it is not easy to read the Scriptures aloud for others.

The reading will better suit the subject matter the more plain and simple it is, the more focused it is on the subject matter, the more humble one’s attitude. Often the difference between an experienced Christian and a beginner comes out clearly when Scripture is read aloud.

It may be taken as a rule for the correct reading of Scripture that the readers should never identify themselves with the person who is speaking in the Bible.It is not I who am angry, but God; it is not I giving comfort, but God; it is not I admonishing, but God admonishing in the Scriptures. Of course, I will be able to express the fact that it is God who is angry, God who is giving comfort and admonishing, by speaking not in a detached, monotonous voice, but only with heartfelt involvement, as one who knows that I myself am being addressed.

However, it will make all the difference between a right and a wrong way of reading Scripture if I do not confuse myself with, but rather quite simply serve, God.Otherwise I become become rhetorical, over-emotional, sentimental, or coercive; that is to say, I divert the reader’s attention to myself instead of the Word—this is the sin of Scripture reading.

If we could illustrate this with an example from everyday life, the situation of the one who is reading the Scripture would probably come closest to that in which I read to another person a letter from a friend. I would not read the letter as though I had written it myself. The distance between us would be clearly noticeable as it was read. And yet I would also not be able to read my friend’s letter as if it were of no concern to me. On the contrary, because of our close relationship, I would read it with personal interest.

Proper reading of Scripture is not a technical exercise that can be learned; it is something that grows or diminishes according to my own spiritual condition.

The ponderous, laborious reading of the Bible by many a Christian who has become seasoned through experience often far surpasses a minister’s reading, no matter how perfect the latter in form. In a community of Christians living together, one person may also give counsel and help to another in this matter.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 1, 2024

Preaching is Possible Only as a Summary of the Doctrine of the Trinity

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber!

In a previous post on the nature of proclamation, I argued that in order to speak gospel the utterance cannot be a mere recitation of past formulas or historic slogans. For the gospel to be itself, the gospel cannot be preached in the same way twice.

The gospel can change— must change, will change— without ceasing to be the gospel because Jesus is at once, simultaneously, the gospel’s fixed object and innovating subject. The ever-changing nature of the gospel is itself an item of tradition, for part of what the rule of faith remembers is that the object of the church’s proclamation lives with death behind him.

Therefore, to be itself, the gospel must change, for part of what the tradition remembers is that Jesus is not dead.

Just so—

The question of how we may speak of Jesus in the present tense and the question of where is Jesus’s present location present themselves as two forms of the same problem.That is, space is to time as the present is to the future and past. The word-relations are key: the presence of something is exactly its presentness. And the Gospel’s clear answer to this problem is that Jesus’s spatial location is the crossing of the lines of communication which bind believers together.

“Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there I AM, in their midst.”

The gospel is thus Jesus happening to us.

There is a single reason why proclamation is not advice or exhortation, teaching or mere talk about God. Namely, the gospel hands over promises only Jesus can rightly promise. The gospel then, spoken by one person to another, is Jesus’s word.

The gospel is his self-address to us.As Robert Jenson writes:

“The gospel promises that Jesus will give himself to us; it promises the total achievement and outcome of his deeds and sufferings as our benefit; it promises his love.

If the gospel occurrence is true, its occurrence is Jesus’s occurrence as a shaping participant in our world. It it the truth of the gospel-promise that is the presence of the promiser.

If the gospel is not true, then when we hear it we hear only each other.”

Of course, proclamation is recollection; for example, as Paul writes to Corinth:

“For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures.”

However, if proclamation is recollection only, then the presence it mediates is not subject presence— it is not promise.

“Insofar as the remembering words are some kind of address to us,” Jenson writes, “the future they pose must be free over against whatever use we make of them; the modification the address makes in our world must be his modification and not ours.”

A promise, meanwhile, opens a future, new and otherwise different, a future otherwise not mine, and so is the presence of a subject other than I. Jesus is present in the gospel in that he is both identified in recollection and the free-shaper of our world in promise. And this is how any of us is present to others as subject.

But, Jenson observes:

In precisely this way, preaching is possible only as a summary of the Doctrine of the Trinity.“The recollection includes that Jesus has died, and is thus recollection of a finished and defined past; and the promise is of the last future, the future of our death. That is to say: the person here present is the person of God.

Gospel proclamation is recollection that points to God— who is never past only, but the future of every past and thus the Presence to every present. To assert the presence of this executed man is to assert a miracle— the miracle that God is.

And this is why God is just and we are in right relationship with him through faith. Not because faith is the one work God demands from us but because the gospel issues promises only God can make, promises we can only take at the word of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

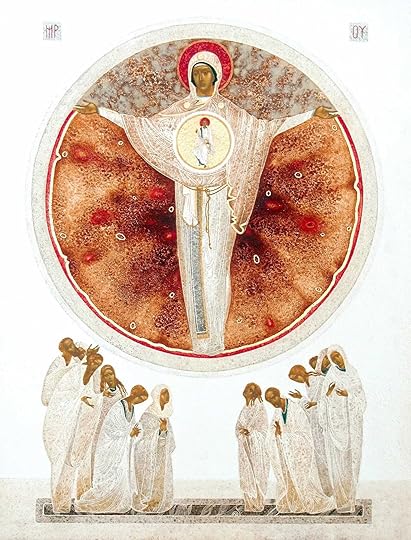

(art: “Preacher Man” by Chris E.W. Green)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 30, 2024

A Good Man is Hard to Find

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Romans 2.1-6, 12-26

I became a Christian when Jesus hijacked my life not long before I graduated from high school whereupon I set out as an undergraduate eager to learn more about the faith that had seized me. My college advisor was a jolly, whiskey complected Jesuit priest named Father Fogarty. Trying to determine my courses for the spring semester of my first year, I met with Father Fogarty one morning before Christmas.

“Father Fogarty, help me out” I said, laying my course catalog on his desk, “This isn’t about my major. It’s personal. I’ve read the four Gospels several times. My pastor gave me some Thomas Aquinas and C.S. Lewis to read and they’ve been illuminating. But other than individual verses and passages, I can’t make heads or tails of Paul’s epistles. No sooner do I start reading his one of his letters than I get lost in his long logic chains.”

“You wouldn’t be the first,” Father Fogarty laughed, sipped his tea, and looked anxiously at his open door, “There’s an entire cabal of biblical scholars who I’m convinced don’t understand Paul either.”

And then he laughed at his own joke.

“Is there a course I could take that would help me understand Paul?”

He reflected on my question for a moment, and then he turned my course catalog a couple of pages and with a red pen circled a listing.

“Register for Willie Wilson’s course on Flannery O’Connor,” he said, “there’s no better guide to help you grasp Paul’s radical message.”

“Flannery O’Connor?” I replied, “I read her in high school— that’s fiction; that’s not theology.”

“Trust me, my boy.”

So I did.

The spring course started with Flannery O’Connor’s grim, gothic short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find” wherein a self-righteous, southern grandmother, who lives with her son Bailey and his family, accompanies them on a road trip from Georgia to Florida. Unsuccessfully, the old lady lobbies Bailey to visit family in Tennessee instead, telling her son that she’s spooked by the news reports of an escaped convict called the Misfit who was embarked on a violent, random killing spree through Florida. At the grandmother’s prodding, the family takes a detour down a dirt road in search of a plantation the old lady remembers having once visited. The grandmother’s stowaway cat causes Bailey to drive into a gulch, flipping the family car. With the car wrecked, the family waits and attempts to flag passersby for help.

Eventually a “big black hearse-like automobile” pulls up slowly to the site of the crash. The car stops and, for “some minutes,” the three men inside stare at them, expressionless. They’re neither neighbors nor policemen but the Misfit and his gang, whom the grandmother has been dreading and decrying during the entire road trip.

One by one, the Misfit sends family members into the roadside woods to be murdered by his accomplices.

Bailey.

His wife.

And their children— John Wesley and June Star and a nursing infant.

Watching her son disappear into the woods, the panicked grandmother pleads for the Misfit’s mercy, saying, “I just know you’re a good man.”

“Nome, I ain’t a good man,” the Misfit says after a second, as if he had considered the statement carefully, “But I ain’t the worst in the world either.”

Her family all murdered, the old lady desperately tries to escape her doom. Since the specter of Jesus apparently offends the Misfit, she goes so far as to suggest that maybe Jesus didn’t raise the dead after all. Delirious with fear, the old lady collapses in the ditch with her legs twisted underneath her. She looks up from the dirt at the Misfit and her head clears for an instant. “Why you’re one my babies,” she says to him, “You’re one of my own children.”

The old lady reaches out to him and grasps him on the shoulder.

He recoils from her touch, “as if a snake had bitten him.”

And immediately he shoots her three times through the chest.

The Misfit then instructs his accomplices to throw her body in the woods with their other victims.

“She was a talker, wasn’t she?” one of them comments to the Misfit.

And the Misfit replies, “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

“There’s no better guide to help you grasp Paul’s radical message,” the priest had promised me.

In his account of Christianity in America, the Yale theologian H. Richard Niebuhr summarized the vague sentimentality of mainline Protestantism. He did so with a brutal and incisive critique:

“A God without wrath brought men without sin into a Kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.”

H. Richard Niebuhr offered that appraisal almost one hundred years ago, and its enduring accuracy can account for why the mainline churches more often than not preach a Jesus kerygma rather than a Christ kerygma. That is, liberal Protestantism typically proclaims Jesus the human teacher, prophet, and example instead of Christ the incarnate, fully divine deliverer from sin.

This privileging of the Jesus kerygma over the Christ kerygma is precisely what has made it difficult for mainline Protestants to make sense of the apostle Paul.All the words Niebuhr said we are without are unavoidably present with this epistle; in fact, they are all packed into this passage.

Wrath.

Sin.

Judgment.

Meanwhile, the fourth word we are without— the Cross— is the revelation of the other three. The negative complement of the gospel, Paul announced in his thesis statement, is the unveiling of God’s wrath. Just so, the gospel is the apocalypse of God's judgment upon humanity’s sin.

A God without wrath brought people without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the work of a Jesus without a cross. If the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church, then the assimilation of the church to the world— a world that does not want to hear words like sin, judgment, and wrath— silences her witness. Therefore, the apostle’s argument demands attention, perhaps most especially Paul’s diatribe which begins chapter one and extends through chapter three.

First—

Understand that Paul reasons from solution to plight, from deliverance to dilemma, from Golgotha back to the Garden.The news that Israel’s Messiah had come would not itself have forced Paul to reassess his Jewish beliefs. The news even that God had raised a dead messiah from the grave would not itself have forced Paul to rethink his convictions, resurrection being a Jewish belief.

It is the crucified Jesus encountering him that compels Paul to reevaluate his received beliefs about sin, the law, and even the narrative thread upon which scripture hangs together. If the crucifixion of Mary’s boy was not, as Saul was taught to believe, a sign of God’s curse, if the crucifixion of God’s Son was instead required to redeem humanity, then the sinfulness of humankind must be both radical in itself and beyond the capacity of existing (and less drastic) measures to overcome it.

As Karl Barth comments on the passage:

“From the verdict of the Father, we learn what God knows about us and therefore how it really is with us…For only the revelation of salvation can throw light on the state of alienation. It is at the cross of Christ that the justified man [or woman] measures the significance of human sin.”

From solution to plight.

Paul’s diatribe begins from this point of post-conversion reevaluation of our plight. The depth of our dilemma shapes his diatribe. Notice, as Paul transitions from his all-encompassing indictment of humanity at the end of chapter one to the beginning of chapter two, he shifts from the third person plural (they) to the second person singular:

“Therefore— you there— you have no excuse, whoever you are, when you judge others; for in passing judgement on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, are doing the very same things.”

What things?

The opening word dio (therefore) signals that what follows draws out implications from the previous section.

Thus:

The hardest people for Christ to win are those who think they need him not. Therefore, Paul proceeds to unpack who is included in that you.“They were filled with every kind of wickedness, evil, selfish ambition, malice. Full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, craftiness, they are gossips, slanderers, God-haters, insolent, haughty, boastful, inventors of evil, rebellious towards parents, foolish, faithless, heartless, ruthless. They know God’s decree, that those who practice such things deserve to die.“Therefore— you there— you have no excuse, whoever you are, when you judge others; for in passing judgement on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, are doing the very same things.”

And Paul does so methodically in chapter two in order to destabilize assumptions about who might be exempt from God’s judgment and who might be immune from his wrath.

To the Gentiles, who might presume that they are not liable to indictment under the Jewish law, Paul insists that they cannot plead ignorance. They know God’s moral will just as well as Jews do. The law merely tells it like it is; the law does not make it so. Moses knew murder was wrong long before God gave him the commandments on Mt. Sinai. Just so, God will judge each and every unbeliever according to their obedience to the law that is written not on tablets of stone but on their hearts.

And to the Jews, who might rest assured that their election as God’s people safeguards them from condemnation, Paul subverts the stability of Jewish identity in the bluntest, crudest manner imaginable. In verse twenty-five, Paul literally says that a circumcised male who does not keep the commandments grows a foreskin. It was difficult for me not to title the sermon, “How to Grow a Foreskin.”

“God shows no partiality,” Paul writes, sweeping everyone up behind the defendant’s table, “All who have sinned apart from the law will perish apart from the law, and all who have sinned under the law will be judged by the law.”

The logic chain is inexorable and exhaustive so that the claim is explicit.

Namely, all other differences notwithstanding, the religious and the irreligious share one common fact; they are all on the very same footing before Almighty God.Or, as Karl Barth writes:

“God alone is the Merchant who can pay in the currency of eternity,” and he alone “will judge the secret thoughts of all.”

We might be good men and women…

If we had someone to shoot us every minute of our lives.

Francis Schaeffer was a philosopher and theologian who wrote extensively on Christianity’s engagement with secular culture. In his book The Church at the End of the 20th Century, Schaeffer sought to convey the logic of Paul’s gospel to readers for whom words like wrath, sin, and judgment might sound archaic.

Imagine, Schaeffer writes:

“If every little baby that was ever born anywhere in the world had an invisible recorder hung about its neck, and if the recorder only recorded the moral judgments with which this child as he or she grew bound other people, the moral precepts might be much lower than the biblical law, but they would still be moral judgments.

Eventually each person comes to that great moment when he or she stands before God as judge. Suppose, then, that God simply touched the recorder's button and each man or woman heard played out in his or her own words all those statements by which he or she had bound others in moral judgment [every instance of him or her saying ought, should, or must to another person]/ She or he could hear it going on for years—thousands and thousands of moral judgments made against other people and moral exhortations given to other people.

Then God would simply say to the person, though he had never head the Bible, now where do you stand in the light of your own moral judgments? Every last person would have to acknowledge that they have deliberately done those things which they knew to be wrong. Nobody could deny it.

We sin two kinds of sin. We sin one kind as though we trip off the curb, and it overtakes us by surprise. We sin a second kind of sin when we deliberately set ourselves up to fall. And no one can say he does not sin in the latter sense. Paul’s comment is not just theoretical and abstract, but addressed to the individual— any person without the Bible, as well as the person with the Bible…

God is completely just.

A person is judged and found wanting on the same basis on which he or she has judged others.”

As much as his encounter with the Risen Jesus forces him to reassess many of his received beliefs, Paul’s understanding of God’s judgment is not different from Saul’s understanding of it.

This is a common misperception of Paul’s message. The gospel promise of the New Testament does not supersede the Old Testament’s principle of law. Law and gospel are two distinct words of God, but the latter does not supplant the former.When Paul writes that no one can be justified by works of the law, Paul is not attacking good works or the law. Throughout the Old Testament, the Lord promises that he will execute his righteous judgment according to each person’s deeds. Simply, God will reward those who do good and punish those do wrong. “He will come again,” the creed confesses, “to judge the quick and the dead.”

As the Lord attests to Moses in the Book of Deuteronomy:

“If you obey the commandments of the Lord your God that I am commanding you today…then you shall live. But if your heart turns away and you do not I declare to you today that you shall perish…I call heaven and earth to witness against you today that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Choose life so that you may live.”

Paul makes the very same claim in verse thirteen, “The doers of the law will be justified.” This is neither a distortion in Paul’s logic nor a contradiction of his gospel.

God will find righteous any one who keeps all the law’s commands.God will find righteous any one who does no wrong under the law.The dilemma is that there are no such good people.If only we had someone to shoot us every minute of our lives.

As I read Flannery O’Connor’s short story in college, I remembered my high school English teacher telling our class that the short story was about hypocrisy, that ultimately every religious person is a phony who will do whatever they can— even renounce God— to save their skin.

I offered this summary in class when we discussed “A Good Man is Hard to Find.”

“Your high school teacher must not have been a Christian,” the Professor replied, “Because it’s not just a story about religious hypocrites. Of course we’re all hypocrites. But the story’s about Paul’s gospel. It’s a parable of God invading our world in word and sacrament to reach out and draw sinners back to him, despite our resistance.”

“I don’t see it.”

“When the grandmother falls down at the end,” he explained, “Flannery says that “her head cleared for an instant.” Then she looks at the Misfit, calls him one of her babies, one of her own children, and then she reaches out to touch him. It’s an instance of grace. In that moment, she finally saw the Misfit and herself as alike under sin, as members of the same fallen family.”

“Then why does the Misfit react like he’s been snake bit and shoot her?” a classmate asked.

“Because,” he said, “if you don’t think you need it, then you recoil at a mercy that lumps all of us together in our need.”Really, Paul’s long, complex diatribe is reducible to a syllogism:

Since no human beings can be righteous in God’s sight by works of the law.

And since the works of the law amount to the good God does require for righteousness.

It therefore follows that no human can be righteous by the deeds they do.

Of course, you can always nevertheless try.

Go for it!

God’s word abides.

What the Lord promised to Moses still holds.

God will find righteous any one who keeps all the law’s commands.God will find righteous any one who does no wrong.Such a one will live and perish not.The dilemma is that there are no such good people.Or rather, there was one.There was one.And he didn’t need a gun to his head.He was obedient even unto a cross.And that’s why the Father raised him from the dead.As the Misfit says to the old lady before her murder, “Jesus was the only One that ever raised from the dead, and he shouldn’t have done it. He thrown everything off balance.”

A God with wrath brings men and women with sin into a Kingdom with judgment through the work of Christ with his cross. Jesus has thrown everything off balance.

God’s word abides.

God’s word abides unalterably.

The Lord will find righteous any one who keeps the law.

That one will live.

Just so, the gospel, according to Paul in verse sixteen, unveils to all a choice— a choice made possible by Jesus having thrown everything off balance.

On the one hand, you can seek righteousness by keeping all the law’s commands, both in act and intention.

Or, on the other hand, you can receive righteousness by obeying the law of faith.

That is, on Judgement Day you can ask God to review your resume vis a vis the commandments, or, you can stand, alongside a whole lot of misfits, under the umbrella of Jesus Christ’s obedience.

The law still stands.

Grace is the choice.

As it turns out, Father Fogarty was telling the truth. Flannery O’Connor was a good guide to grasp Paul’s gospel. Only, the title of her story is wrong. A good man isn’t that hard to find.

You have just heard from him.

And he’s told you where to find him.

So come to the table.

Reach out and grasp him.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 29, 2024

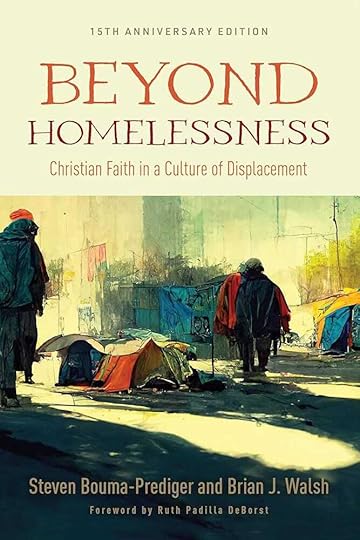

Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in a Culture of Displacement

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Here is a conversation with Steve Bouma-Prediger and Brian J. Walsh on the new edition of their book, Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in a Culture of Displacement.

Steve Bouma-Prediger is the Leonard and Marjorie Maas Professor of Reformed Theology at Hope College. He speaks regularly on environmental issues.

Brian J. Walsh served as a campus minister and adjunct professor of theology at the University of Toronto. He farms at Russet House Farm in Ontario and serves on the board of his local homeless shelter.

Their book goes far beyond covering the subject of homelessness as the social problem we all recognize in our cities. Mass emigrations, displaced families, and human alienation from the earth all mark our times. In critiquing contemporary North American culture, Steven Bouma-Prediger and Brian Walsh discuss various forms of homelessness -- socioeconomic, ecological, and psycho-spiritual -- and creatively show how biblical attentiveness and Christian faith can heal the profound dislocations in our society. Ending each of their chapters with a moving biblical meditation, the authors also interact throughout with characters and themes from current literature and popular culture -- from Salman Rushdie to Barbara Kingsolver, from the Wizard of Oz to Bruce Cockburn.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 28, 2024

Whenever Christians Use a Construction like "Christianity and Politics" They Open the Door to Every Devil

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, give thanks I don’t have an Only Fans by becoming a paid subscriber.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus praises Mary’s lavish anointing of him because Mary understands that Jesus makes a different politics possible. To put a finer point on it, Mary understands that she-and-her-nard constitutes the different politics which God has made possible in the world in Jesus. Put differently, Mary intuits that Jesus is the difference God has made in the world.

Karl Barth, the theologian on whom I cut my teeth and who remains my north star, wrote:

“Whenever Christians use a construction like Christianity and Politics they open the door to every devil.”

Barth liked to point out how when the devil temps Christ in the wilderness by offering him the governments of this world the implication is that the governments of this world are the devil’s to give. They belong to him.

Barth, who was one of the only German Christians to stand up against Hitler’s Nazi regime, was not being hyperbolic.

“Whenever Christians use a construction like Christianity—and—Politics they open the door to every devil.”

It’s the and there that’s problematic.Just as soon as the church begins to ponder how its Christianity can inform politics, Barth argued, you can be sure the church has lost the plot.Such a church might be a church of great sincerity and zeal. Such a church might be a church of fervent devotion and good works of charity. Nonetheless, such a church will be a church that’s failed to understand that it is the way God has chosen to love and redeem the world. Whenever we talk about Christianity and Politics, we risk forgetting that the way God has chosen to heal his creation is through his particular People— that’s a promise that goes all the way back to Abraham.

The way God has chosen to heal his creation his through the witness of his People.

Not the House or the Senate.

Not POTUS or SCOTUS.

Not with bills or billboards or hashtags.

Not through political policy.

But his People.

The Church.

The Body of Christ, sent by the Spirit, is God’s virtue signal; that is to say, the Church doesn’t have a politics the Church is a politics. The church is not sent to make the world different so much as it is called to live the difference Christ makes.

I’m sure right about now that some of you (if not all of you) are thinking Well, gee Jason, that sounds nice but what in the hell do you mean“The Church doesn’t have a politics. The Church is a politics?”

I’m glad you asked.

Yesterday afternoon we celebrated a Service of Death and Resurrection for a man in the community, Gordon.

Gordon was a Vietnam vet. The cancer that killed him likely came from Agent Orange that killed others. A couple of days before he died, he called me to his bedside. In addition to wanting to profess that Jesus is Lord and give to Christ what remained of his life, Gordon also wanted to confess his sins.

“I want to confess,” he told me staring at the ceiling, “what I had to do in the war— it was necessary, but it was still sin.”

Think about it—

He was dying. He didn’t know how quick. Time was a precious, valueable commodity to him. Time was a gift, and Gordon wanted to give it, to lavish it— some would say waste it— by giving his confession to Christ.

In a culture that ships our soldiers off to do what is necessary and then, when they return home, we insist that they not tell us about what we’ve asked them to do, Gordon’s confession— what the Church calls the care of souls— that’s a politics.

It’s how God has chosen to care for the world.

During the funeral service, Gordon’s son spoke candidly about his often difficult sometimes estranged relationship with his father.

In a culture of sentimentality and pretense, the sort of truth-telling that this sanctuary makes possible— make no mistake, that’s a politics.

A while ago, I read a story in the paper about the California Prison Hospice Program. The unintended consequence of stiff prison sentences doled out in the ‘80’s and ‘90’s is that now many penitentieries must double as nursing homes. Already underfunded, many prison systems have recruited and trained convicts to serve as hospice workers to care for and accompany aging inmates as they die of cancer and other causes. It might not surprise you to hear most of the prisoners who volunteer to care for the dying are Christians.

“It’s what God’s given us the opportunity to do, to pour out our love on them” one prisoner— guilty of a gang bang in his youth— told the New York Times.

It might not surprise you to hear that most of the hospice workers are Christians, but it might surprise you to hear that of the hundreds of prisoners who’ve worked caring for the dying and later been released not one of them has returned to prison. They have a recidivism rate of 0%. In a culture where even Democrats and Republicans can agree our criminal justice system is broken, a simple unimpressive act, Christian care for the dying...zero percent— that’s a politics.

At the end, the Times article unintentionally echoes St. Paul:

“Within the walls of the prison hospice, all the invisible boundaries of the world have fallen down. Black men give meal trays to [dying] white men with swastikas tattooed on their faces, Crips play cards with Bloods, and a terminal Latino with cirrhosis gets his hair cut by an Asian with whom he previously wouldn’t have peaceably shared a cellblock.”

The way God has chosen to heal the world is the church— that’s what we forget whenever we argue about the Church and Politics. We’re the nard that God has purchased at great cost to himself to lavish Christ upon the dying world. It’s not that grace— what God has done for us in Jesus Christ— makes what we do as Christians incidental or unimportant. It’s that what we do as Christians should be unintelligible— an expensive waste, even— if God has not raised Jesus Christ from the dead.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 27, 2024

The Gospel is Jesus Happening to Us

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber. Much appreciate to those who do!

In writing recently about the Reformers’s distinction between historical faith versus lively faith, I made the following assertion.

To be itself, the gospel changes.Indeed as the power of lively faith, the unconditional promise called gospel can never be preached the same way twice because the promise must address the living hopes and fears of its actual hearers. That the gospel can free from any and every bondage is its peculiar, all-encompassing power of which Paul announces that he is not ashamed. Just so, for the gospel to be itself, I cannot, in my attempts to gospel another, merely repeat biblical verses or Sunday School formulas. The gospel must proclaim Jesus as the hope of new possibilities and unique fears that present themselves today.

The criterion for whether the gospel is gospel, then, is simply whether the proclamation is 1) promissory in nature— and, as promise, it logically presents God as the primary protagonist of the story you call you— and 2) whether it sets sinners free for the future.

To be itself, the gospel changes.

This leads to the question a reader submitted in response.

“Just how does the gospel change without ceasing to be the gospel? We’re all aware, I imagine, of churches that, in the desperate quest for relevancy, have seemingly lost the gospel? What is to prevent the gospel from getting lost if it does not merely repeat the tried and true formulas of the tradition?”

The answer is Jesus.

In commenting on Karl Barth’s work on the Barmen Declaration, the theologian Eberhard Busch, summarized the third thesis with the warning, “Woe to the church who speaks of Jesus in the past tense!” The apparent simplicity of the admonition is deceptive as it is but a reminder of the dogma established by the Second Helvetic Confession:

“The preaching of the word of God is the word of God.”That is— Jesus is both gospeling’s object and its subject.

As the crucified Jesus, Christ is the object of gospel proclamation. He is, as Robert Jenson says, “the given about whom we speak.” Canon and creed establish his objective identity; so that, the church who still seeks him there will not wander from his gospel. However, just as the church is not the Jesus Memorial Society, the gospel is not simply the spoken memory of the crucified Christ. In fact, the church would have no word of the cross if Christ were crucified only.

The church would have no word of the cross if Christ were crucified only.

As risen, Jenson writes, "Jesus is the final future who ever opens new promises beyond those already made.” All gospeling is in the power of his Name and to him; so that, the Risen Jesus is the free subject of the address, initiating its surprising twists and new beginnings.

Thus, the gospel can change— must change, will change— without ceasing to be the gospel because Jesus is at once, simultaneously, the gospel’s fixed object and innovating subject. And this claim about the nature of the gospel rises to level of dogma exactly because part of what we remember about the fixed object is that he lives with death behind him.

To be itself, the gospel must change, for part of what the tradition remembers is that Jesus is not dead.

Jesus is free future not dead past.For the gospel to be gospel, in other words, it must bear two marks of authenticity. It must be talk of Christ that is:

Faithful to the remembered Jesus

Free response to the futurity of Jesus

Once again, the gospel is not a word about Christ.

It is Christ’s own word.

The gospel, as Jenson says, is Jesus happening to us.

(art: “Preacher Man” by Chris E.W. Green)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 26, 2024

God is in the Yes Business

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

I am excited by the feedback I’ve received from some of you listening, viewing, and reading along with us.

If you’d like to join us on Mondays at 7:00 EST, the link is always THIS.

And here is the PDF of Barth’s Church Dogmatics: II.2

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

Show Notes

Summary

In this conversation, the participants discuss the concept of election and its implications in Christian theology. They explore the idea that Jesus Christ is the electing God and how this understanding challenges natural theology and sloppy God talk. They emphasize the importance of proclaiming the gospel and the need for sermons that focus on the profound sinfulness of the world and the active agency of God in our lives. The conversation also touches on the themes of time, eternity, and the nature of God's choice in Jesus Christ. The conversation explores the concept of election and its connection to the person of Jesus Christ. It emphasizes the present reality of election and the importance of living in the mystery of who Jesus is. The conversation also highlights the need to move away from doctrinal rigidity and embrace the ongoing revelation of God's love. The chapters cover themes such as the present nature of election, the freedom of God in election, and the resonance and reflection in the octaves of God.

Takeaways

Jesus Christ is the electing God, and understanding this challenges natural theology and sloppy God talk.

Sermons should focus on the profound sinfulness of the world and the active agency of God in our lives.

The concept of election involves understanding time, eternity, and the nature of God's choice in Jesus Christ.

Receiving and engaging with scripture should be done with a sense of wonder and openness to encountering Jesus. Election is not just a past event, but a present reality that is attached to the person of Jesus Christ.

Living in the mystery of who Jesus is allows for a deeper and more vibrant relationship with Him.

We should embrace the ongoing revelation of God's love and not limit it to rigid doctrines.

God's freedom in election is the freedom to be who He is, a God of love and compassion.

Resonance and reflection in the octaves of God is a metaphor for the dynamic engagement with God's love that resonates with our lives.

Sound Bites

"The reduction of the gospel to exhortation and lettuce sermons is heartless preaching."

"Everything in the world is ordered for you to know this. That's amazing."

"To receive the prologue is to marvel, to be moved to tears, and to just hear."

"Election is not just a decision or decree, it is attached to the person of Jesus."

"Living in the present sense of the mystery of Jesus opens us for delight."

"We are incognito ergo sum. We hide so that we can feel okay about ourselves."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 25, 2024

In the name of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit- Mother of us all

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward and become a paid subscriber!

The triune name of the true God reminds believers that there is no other God than the God who has identified himself with the particular history he has made with Israel and her servant Jesus. The God of Israel is the Father who raised that Son from the dead in their Spirit.

“Trinity” thus names an historical record.

More pragmatically, Trinity also serves as a linguistic rule, enabling Christians to speak of God as the scriptures do. God is Father not generically but because Jesus addressed HaShem as Abba— Daddy. God is this Son because the Father raised him up from death into his own life. God is the Holy Spirit because the Son promises to send the Paraclete as his own abiding presence. Just so, the way the Bible speaks of God presupposes that God is a community within Godself.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers