Jason Micheli's Blog, page 37

July 16, 2024

No One is an Enemy of God: On Romans

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a recent conversation with one of my favorite former teachers, Beverly Gaventa, about her new commentary on Romans. You can purchase it here.

Beverly is Helen H. P. Manson Professor Emerita of New Testament Literature and Exegesis at Princeton Theological Seminary. Following her retirement at Princeton, she served as Distinguished Professor of New Testament at Baylor University. In 2016, Gaventa was president of the Society of Biblical Literature. The British Academy awarded her the Burkitt Medal for Biblical Studies in 2020 for her long and distinguished contributions to New Testament scholarship. Her publications range from commentaries on the Acts of the Apostles and the Thessalonian correspondence to studies of Mary, the mother of Jesus, and explorations of maternal imagery in the letters of Paul.

In this new contribution to the New Testament Library, renowned New Testament scholar Beverly Roberts Gaventa offers a fresh account of Paul's Letter to the Romans as an event, both in the sense that it reflects a particular historical moment in Paul's labors and in the sense that it reflects the event God brings about in the gospel Paul represents.

Show NotesSummary

In this conversation, Beverly Gaventa discusses her new commentary on Romans and the themes within the book. She talks about the last time she cried and the hymn that moved her to tears. She also shares her experience as a parishioner in her son's church and the challenges of preaching Paul's letter to the Romans. Gaventa highlights the importance of understanding the concrete audience of the letter and the role of women in interpreting and delivering it. She emphasizes the need to move people through the letter rather than simply arguing at them. Gaventa also addresses the issue of power and how the recipients of the letter were not the powerful and influential at the center of the empire. She suggests starting with Romans 16 to help people see the diversity of the recipients. Gaventa concludes by discussing the challenges of preaching Paul and the tendency to abstract the letter from its concrete context. In this conversation, Beverly Gaventa discusses the radicality of Paul's gospel and the challenges it presents. She highlights how Paul's unique perspective and interpretation of Scripture can lead to dangerous misunderstandings. Gaventa emphasizes the importance of reading Scripture through the lens of the Christ event and allowing it to speak to us in new ways. She also addresses the difficulties faced by candidates for ministry and offers insights on how to navigate the tension between faithfulness to Scripture and the freedom to proclaim the gospel. The conversation concludes with a discussion on the message of Paul's letter to the Romans, which centers on God's power to redeem and remake the world.

Takeaways

Understanding the concrete audience of Paul's letter to the Romans is crucial for interpretation.

The role of women, like Phoebe, in interpreting and delivering the letter should not be overlooked.

Preaching Paul's letter requires moving people through the text and addressing the tension and challenges it presents.

The recipients of the letter were not the powerful and influential, but rather a diverse group of people.

The themes of power, faith, and the tension between what is promised and what is resonate throughout the book of Romans. Paul's gospel is radical and can lead to dangerous misunderstandings if not approached with caution.

Reading Scripture through the lens of the Christ event allows for new and transformative interpretations.

Candidates for ministry should strive for a deep understanding of individual texts and engage in ongoing study and reflection.

The message of Paul's letter to the Romans is centered on God's power to redeem and remake the world.

Sound Bites

"Our concluding hymn was This Is My Song... and it always causes me to, causes my eyes to leak a little bit."

"I think we live in that tension. There's no escaping."

"The gospel is something that has happened in the recent past for Paul. It is something God has and is doing."

"Paul presses so hard on the divine initiative... that sometimes we are led into territory that is really quite not just frightening, but dangerous."

"We have to let him, we have to hear that."

"The scriptures is like this living tradition that we can use for the purpose of proclamation."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 15, 2024

Paul's Big But and the Life of Faith

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider a paid subscriber!

From the cutting room floor…

Here’s a move in Sunday’s sermon that got cut for time. Paul’s big but in Romans 3.21 is not only rhetorically powerful and theologically crucial, it is essential to the life of faith.

When the little voice inside your head rears his forked tongue and suggests that you are not really a Christian— indeed that you have never been a Christian— because of what is still in your heart, or because of what you are still doing, or because of something you once did, or because of the doubts you yet harbor in your mind— when the devil comes and thus accuses you, what do you say in response?

Do you agree with what your conscience’s attacks?

Or do you cling to this little word and reply, “Yes, that may be true, but now…”

Do you hold up these words against him? Or when, perhaps, you feel condemned as you read the scriptures, especially God’s first word— the law, and as you feel that you are undone, do you remain lying on the ground in hopelessness, or do you lift up your head and say, “But now?”

This is the essence of the life of faith.

This is how faith answers the accusations of the law, the accusations of the conscience, the accusations of the Enemy, and everything else that would condemn and depress us.

“But now!”

Faith is a kind of protest.All things seems to be against us. Very well, are you a person of faith or not? That is the vital question and your answer to it proclaims what you are. Having listened to all that can be said against you, and in the most grievous circumstances, do you then say, “But now?” That is part of the fight of faith. Do not imagine that as a Christian you are going to be immune to the assaults of Satan to attacks of doubt. They will certainly come. But the whole secret of faith is the ability to stand up with these words against it all.

Faith means perpetual unbelief kept quiet, like the snake beneath Michael’s foot.The snake wriggles and tries to get at the angel to bite him; but as long as Michael keeps his pressure firm upon the neck of the snake it cannot harm him. On top of all the wriggling of doubt and unbelief and denial, and all these accusations, faith keeps its foot firmly down and say, “But now!”

“But now, without the law’s involvement, God’s righteousness has been made plain, although it is confirmed by the law and the prophets, that is, God’s righteousness through Jesus Christ-faith for all who believe (for there is no distinction, since all have sinned and are deprived of the glory of God, yet all are rectified freely through God’s grace through the liberation from slavery that comes about in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as the very cover of the ark of the covenant.

God did this through God’s own faithfulness, by means of Jesus’ bloody death, as a demonstration of God’s righteousness because of the incapacity resulting from previous sins and through God’s forbearance, as a demonstration of God’s righteousness at the present time so that God might be right and might make right the one who is part of this Jesus-faith.”

*paraphrase of Martyn Lloyd-Jones

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 14, 2024

Something has Happened that has Changed Everything for Everyone for Always

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Romans 3.21-26

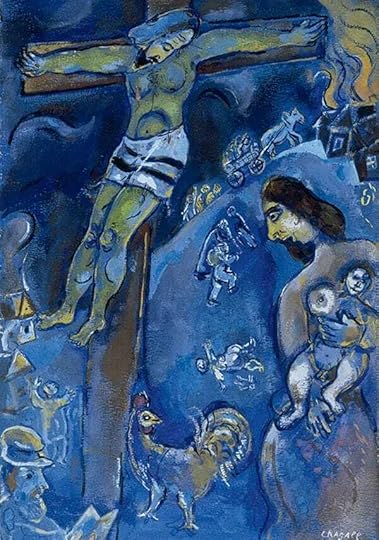

In November 1993, at the Presbyterian “Re-imagining Conference” in Minneapolis, a professor of theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, made a suggestion which was widely quoted in reports of the progressive Christian gathering. The professor said the church’s proclamation needed to depart away from its historic focus upon the cross of Christ:

“I don’t think we need to dwell on atonement at all…atonement has to do so much with death…l don’t think we need folks fixating on the cross, and blood dripping, and weird stuff…we just need to listen to the god within.”

Of course, if the cross is so easily jettisoned from the gospel, then you can be sure “the god within” you is not the Holy Spirit. Never mind that what the New Testament omits are precisely the grisly details of the crucifixion. Romans 3.21-26, what John Stott calls “the most important paragraph ever written,” drives a dagger through the heart of any attempt to preach Christ but not also him crucified.

Paul pivots out of his diatribe:

“But now, without the law’s involvement, God’s righteousness has been made plain, although it is confirmed by the law and the prophets, that is, God’s righteousness through Jesus Christ-faith for all who believe (for there is no distinction, since all have sinned and are deprived of the glory of God, yet all are rectified freely through God’s grace through the liberation from slavery that comes about in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as the very cover of the ark of the covenant. God did this through God’s own faithfulness, by means of Jesus’s bloody death, as a demonstration of God’s righteousness because of the incapacity resulting from previous sins and through God’s forbearance, as a demonstration of God’s righteousness at the present time so that God might be right and might make right the one who is part of this Jesus-faith.”

Quite simply—

We have no other word but the word of the cross.

The Christian faith just is trust in the blood.The Union Seminary professor, however, is not the first person to recoil at the notion of a crucified God, finding the claim a foolish stumbling block.

Saul of Tarsus was among the first to trip over the gospel.

Keep in mind—

In handing over the commandments to Moses at Mt. Sinai, the Lord issues a condemnation whose clarity allows for no confusion, “Cursed is every one who hangs on a tree.”

Not some.

Not most.

Cursed is everyone who is nailed to a tree.To a pharisee like Saul, therefore, the primal church’s declaration that Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is somehow Israel’s messiah— the gospel— was as absurd as it was anathema. Quite obviously, Jesus cannot be God’s promised deliverer when God’s own law designates him as accursed.

He is not a deliverer.

He is damned.

He is not a savior.

He is shameful.

He is not a redeemer.

He is wretched.

He was crucified.

Accursed is everyone who is nailed to a tree.

And then the risen Jesus commandeers Saul on the road to Damascus.

Blinded, Paul sees.

He sees that if the crucifixion of God’s Son was not merely a sign of God’s curse but the curse was instead required to redeem humanity, then humanity’s captivity to sin must be total in its effect, universal in its reach, and cosmic in its breadth. If the medicine is Christ and him crucified, then the disease is worse than Paul had heretofore diagnosed from his scriptures.

Just so, Paul moves from his opening thesis to a diatribe that endures for nearly three chapters. After announcing the good news, Paul has brace us with agonizingly bad news. For the balance of chapter one, all of chapter two, and the first half of chapter three, Paul bears down with white-knuckles and surveys the extent of our bondage to the Pharaoh called Sin.

All sin is unbelief.As Paul sees, our every sin starts with the same sin as at Mt. Sinai; namely, our failure to worship God as God.

This is why it’s inane to suggest, “I don’t believe in God, but I’m basically a good person.”

According to Paul and his scriptures, without the fear of the Lord, our first sin begets all our other sins, our wickedness and our malice. It gives rise to our greed and our lust and our violence. It spawns our slander and our deceit, our hypocrisy and our infidelity. Even our gossip and our haughtiness and our hardness of heart are all made possible by our disbelief that God hears us or knows the secret thoughts of our hearts.

“All have sinned,” Paul charges, religious and irreligious alike. “No one is righteous,” Paul condemns, “not a single one of us.” “No one seeks God. No one desires peace.” Our mouths are quick to curse, our hands are quick to stuff our own pockets, our feet are quick to shed blood, our hearts are swift to indifference.

How quickly, I wonder, did you forget about the children’s hospital in Kiev that Russia bombed on Wednesday?

Did the war crime bother you as much as the price of your last tank of gas?

The awful truth unveiled by the gospel is that your past and your future have been reduced to a present judgment which no good work and no sincere regret can change.

Paul’s relentless litany of our sinfulness goes on and on for almost three chapters, an overwhelming avalanche of indictments.

For almost three chapters, Paul keeps raising the stakes, tightening the screws, shining the light hotter and brighter on our crimes, implicating each and every one of us.

Until, what you expect to hear next from Paul is the word if.If.

If you turn away from sin…

If you turn back towards God…

If you repent…

If.

If you plead for God’s mercy…

If you beg God’s pardon…

If you clean up your act…

If…

Then…

God will forgive you.

If…

Then…

God will find you righteous.

Paul relentlessly unrolls the rap sheet until every last one of our names is listed in the charging documents. Not one of us is righteous and every last one of us is deserving of God’s wrath, Paul writes. When you follow the logic of the biblical passages Paul piles up at the end of his diatribe, particularly Psalm 143 which lies behind the verse immediately before this passage, the word you expect Paul to use next is if.

If you repent…

If you make right…

If you cry out to God…

No.

Instead of if —but:“But now” Paul declares.“But now, without the law’s involvement, God’s righteousness has been made plain…through Jesus Christ-faith for all who believe….” Martin Luther says this “but now” is a word shaped like a fish hook, and it catches us all.

Sir Mix-A-Lot must love verse twenty-one because there couldn’t be a bigger but.It’s the hinge on which the gospel turns:

We are all unrighteous.

We are all under in sin.

We are all facing wrath.

But now!

You could live to be as old as Methuselah— you could live a billion years—and you would never once put yourself right before God. Time will not help you. Nothing will help you. There is no escape from the righteous judgment of God. There is no exit from his wrath. We could never produce a righteousness that can stand up to God’s searching glance and searing examination and absolute investigation of us.

We are— all together— altogether hopeless.

But now—God!

You were lost.

But now, you’ve been found!

You’ve been found by the righteousness of God made plain in Christ Jesus.

“But now apart from the law— apart from the very thing that was supposed to make us righteous—God’s righteousness has been made plain… through Jesus Christ-faith for all who believe.”

People ask me all the time if there is only one way to salvation.Thank God there is one!People ask me all the time if there is only one way to salvation.

Thank God there is one!

As Martyn Lloyd-Jones writes:

“There are no more wonderful words in the whole of Scripture than just these two little words.”

As strong as the cultural pressure is to reduce Christianity to self-help and sentimentality, the gospel truth is that we are all under sin. We are all unrighteous.

We are all justly condemned and deserving of wrath.

"But now!”Something has happened. Something has happened that has changed everything. Something has happened that has changed everything for everyone. Something has happened that has changed everything for everyone for always.In a sermon to the inmates at the Basel Prison, the theologian Karl Barth attempted to illustrate Paul’s big but by telling them a regional legend.

Barth preached:

“You probably all know the legend of the rider who crossed the frozen Lake of Constance by night without knowing it. When he reached the opposite shore and was told whence he came, he broke down, horrified. This is the human situation when the sky opens and the earth is bright, when we hear “But now!” In such a moment we are like that terrified rider. When we hear this word we involuntarily look back, asking ourselves: Where have I been? Over an abyss, in mortal danger! What did I do? The most foolish thing I ever attempted! What happened? I was doomed and miraculously escaped and now I am safe!

You ask: “Do we really live in such danger?”

Yes, we live on the brink of death. “But now!” From this darkness he has saved you. He who is not shattered after hearing this news may not yet have grasped the word of God, “But now!”

Something has happened. Something has happened that has changed everything for everyone for always.

The god within?

No!

From outside of us, apart from us— apart from the law even— the right-making power of God has invaded our world without a single if.

Preemptive.

Predestined.

One-way love.

Just as these two little words are the hinge of the gospel, they are also the simplest but most thoroughgoing test of a Christian. You can know, right now, whether or not you are a Christian. A Christian is nothing more than one who hears Paul’s big but and responds in their heart, “Thank God!”

Something has happened.

And it has changed everything for everyone for always.

What has happened?

Or, how?

Fleming Rutledge tells the story of a Ph.D. candidate who wrote his dissertation on the subject of forgiveness in process theology. The candidate mounted his oral defense. When he had finished his presentation and after the dissertation committee had discussed his defense for quite some time, a Jewish professor on the panel finally interjected and offered his puzzlement over the student’s work.

“As a Jew,” he told the candidate, “I know that there is no forgiveness without sacrifice. How is it possible you have written an entire dissertation on the subject of forgiveness and theology yet not once mentioned sacrifice? Atonement must be made.”

“But now…” Paul pivots to the good news, “…all are declared righteous freely through God’s grace through the liberation from slavery that comes about in Christ Jesus…”

On its face, stripped of the cross, free justification through grace is not only immoral under God’s law it is incompatible with the scriptures.

How is it possible for the righteous God to declare the unrighteous righteous without either compromising the Lord’s own righteousness or condoning their unrighteousness? Straightforwardly, it is unjust for God to justify the wicked. Straightforwardly, it is unjust for God to justify the assassin in Butler, Pennsylvania.Again and again in the Bible, the Lord commanded the judges of Israel that they must justify the righteous and condemn the wicked. The Book of Proverbs insists that the Lord detests both the acquittal of the guilty and the condemnation of the innocent. To the prophet Isaiah, the Lord lays down a heavy “woe” against those “who acquit the guilty for a bribe, but deny justice to the innocent.” And to Moses on Mt. Sinai, God promises that he is a God of justice, “I will not acquit the guilty.”

How then can the apostle Paul declare that God does exactly what God forbids? How can Paul say that God does what God himself says he will never do, that is, acquit the guilty? To say that God is a God who justifies the ungodly is an oxymoron. How can the righteous God act unrighteously without invalidating his own moral intent?

Blinded, Paul sees.

Looking back upon his scriptures, Paul sees that in the crucified Christ God has unveiled what once was veiled. “But now…God’s righteousness has been made plain…all are declared righteous freely…in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as the hilasterion”

Often translated as “propitiation” or “expiation,” hilasterion is the Greek equivalent for the Hebrew term kapporet. Literally, the word refers to the cover of the ark of the covenant.

God the Father put forward God the Son as the lid of the ark.The kapporet is also known as the mercy seat. In the Book of Exodus, when the Lord culminates his instructions for the construction of the ark, God promises, “There I will meet you, and from above the mercy-seat…I will deliver you and make myself known to you.” Once a year on Yom Kippur, Israel’s high priest would venture beyond the temple veil and into the holy of holies in order to sprinkle the blood of sacrifice on the kapporet to make atonement for his people’s sins.

Ever since its construction in the wilderness, the mercy seat— made of wood— had been veiled from human eyes. “But now…” Paul sees, God has unveiled the meeting place of God’s mercy, once for all.

The Father in the Spirit put forward the Son as our atonement cover. In Christ, on the cross, God meets us and gives us everlasting mercy. Something has happened that has changed everything for everyone for always.How is it possible for the righteous God to declare the unrighteous righteous without either compromising the Lord’s own righteousness or condoning their unrighteousness?

The only reason is that Christ died for them.

According to the Book of Exodus, two golden angels, their wings outstretched, faced each other across the cover of the ark of the covenant.

In reality, it was not two angels but two criminals.

And the mercy unveiled between them made possible his promise for them, “Today, you will be me in Paradise.”

Like them, all we need to do is trust his promise.

To still other criminals, Karl Barth continued his prison sermon by preaching:

“You ask: “Do we really live in such danger?”

Yes, we live on the brink of death.

“But now!”

We have been saved…Look at our savior and our salvation! Look at Jesus Christ on the cross, accused, sentenced, and punished instead of us! Do you know for whose sake he is hanging there?

For our sake— because of our sin— sharing our captivity—burdened with our suffering. He nails our life to the cross. This is how God had to deal with us.”

Perhaps that professor of theology was partially correct. Maybe it is “weird stuff” to trust in the blood. But on at least one count she’s wrong.

The cross is not about death. It’s about life.“God unveiled Christ Jesus as the mercy seat…God did this through God’s own faithfulness, by means of Jesus’s bloody death…so that God might be right and might make right the one who is part of this Jesus-faith.”

A 2016 episode of the NPR show Invisibilia entitled “Flip the Script,” reported on the true story of two cops named Allan and Thorleif, in the city of Aarhus in Denmark. Back in 2012, the officers Allan and Thorleif received a phone call from distraught parents— distraught Muslim parents— that their teenage son had gone missing. As Allan and Thorleif began investigating, other calls from other parents began to cascade into the police station until eventually over thirty teenage sons of thirty sets of parents were missing. When the Danish cops scratched the surface, asking questions and interviewing people in the community, they began to hear rumors.

About Syria— about how these teenage boys had been radicalized without their parents realizing, about how they’d fled to join ISIS and take up jihad.

For whatever reason, these two ordinary, unimpressive cops, who don’t even have sexy cop jobs— they work in neighborhood crime prevention— they took it upon themselves to determine what they were going to do about these missing boys if ever and whenever they returned to Aarhus. For all the cops knew, when these boys came back, their town would be receiving dozens of angry terrorists. Again, this was 2012 when other countries were pulling no punches when it came to potential threats, pulling out all the stops to detain and prosecute anyone suspected of affiliation with ISIS. And in 2012, the city of Aarhus was second on the list of European countries with a homegrown terrorist problem.

But then Allan and Thorleif elected to act in a surprising, counterintuitive, unmerited manner.

They chose beforehand—

Before any of these teens even returned back from Syria. Before a one of them ever fessed up, expressed remorse, or repented. Before Allan and Thorleif found out what the missing boys had done. Before investigating what the would-be terrorists might’ve deserved.

Apart from the law!

They flipped the script. They chose beforehand, before any of them showed up on the scene, they predetermined to declare them righteous and show them mercy. Before a one of these aspiring jihadists appeared back in Aarhus, these two ordinary cops chose to impute to them a goodness wasn’t even there. They chose beforehand to call these teens what they were not— not terrorists. They chose to call them “Syrian Volunteers.” They chose beforehand to treat them, no matter what they may have done or likely did do, as though they’d been volunteering in hospitals and orphanages and refugee camps. The two cops chose to credit to the missing boys a righteousness that was not theirs, and they chose not require them to do anything to earn it.

And then!

As these missing jihadi teens trickled back home, Allan and Thorleif didn’t meet them at the airport and arrest them. No, they welcomed them home. Later, they’d invite them to coffee to chat. They connected them with mentors. They got them back in school and back into jobs.

Of the thirty-four Aarhus teens who first went missing, six were killed in Syria and ten went missing. The remaining eighteen who returned home were all de-radicalized— rectified— by the one-way love of those two men. Afterwards, they did the same for over three hundreds teens.

We decided to fight radicalism with love…” Thorleif told the Invisibilia host, but he noted that such love was not without cost. Their decision, he said, risked sacrificing their careers and reputations and how befriending terrorists put them in harm’s way.

“We didn’t wait for them to find their way back into the light; we chose not to let them leave themselves in the dark,” Allan told the reporter.

Here’s the point of Paul’s big but:The three person’d God is just like those two cops.Come to the table.

This God who gave himself for you gives himself still to you.

The table is now the meeting place of his mercy.

Feed on him in your hearts by faith.

And you will indeed have God within you.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 13, 2024

Deliberating War

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

“If we are in an apocalyptic battle between Good and Evil, then there is no place for the everyday politics of compromise, deliberation, fairness, reciprocity. What initially seems to be an effective solution (hyperbole and demagoguery) to an immediate rhetorical problem—how do I persuade people to adopt a policy (or support me) without relying on policy argumentation, since that probably wouldn’t work?—is a trap. At some point, hyperbolic rhetoric becomes threat inflation, and then that inflated threat becomes the premise of policies, both foreign and domestic. And then agreeing as to the obvious existential threat posed by the Other and uniting behind the obvious policy solution is a necessary sign of being on the side of Good. Thus, the rhetoric of existential war inevitably has democratic discourse itself as one of the first casualties.”

Here is a recent conversation my friend Johanna Hartelius and I had with Patricia Roberts-Miller about her new book, Deliberating War.

Formerly Professor of Rhetoric and Writing and former Director of the University Writing Center at the University of Texas at Austin, Trish retired from full-time teaching in order to have more time for writing, hosting workshops, visiting campuses and classrooms, podcasts, and any other way she can get people to listen to her. She is also the author of Speaking of Race: How to Have Antiracist Conversations that Bring Us Together(Experiment 2021), Rhetoric and Demagoguery (2019), Demagoguery and Democracy(2017), Fanatical Schemes: Proslavery Rhetoric and the Tragedy of Consensus (2009), Deliberate Conflict: Argument, Political Theory, and Composition Classes (2004), and Voices in the Wilderness: Public Discourse and the Paradox of the Puritan Rhetoric (1999).

Show NotesSummary

Patricia Roberts-Miller, an expert in rhetoric, discusses the power of language and the dangers of demagoguery in public deliberation. She explores how people talk themselves into making unforced errors and the regret that often follows. She also examines the framing of politics as war and the impact it has on democracy. The conversation touches on topics such as slavery, Nazism, and the current political climate. Roberts-Miller emphasizes the importance of respectful disagreement and the need for effective methods of handling conflict. In this conversation, Patricia Roberts-Miller discusses the importance of deliberation in political discourse and the dangers of rhetoric that aims to win rather than seek truth. She emphasizes the need for genuine disagreement and the ability to change one's mind. The conversation also touches on the challenges of teaching rhetoric in a polarized society and the impact of cancel culture on open dialogue. Roberts-Miller highlights the role of identity in shaping arguments and the need for reconciliation and understanding. Overall, the conversation explores the consequences of war-like rhetoric in politics and the importance of thoughtful deliberation.

Takeaways

Language has the power to shape public deliberation and can lead to unforced errors and regrettable decisions.

Framing politics as war can be detrimental to democracy, as it creates an environment of extreme polarization and demonization of the other side.

Respectful disagreement and effective methods of handling conflict are essential for a functioning democracy.

Understanding the historical context and consequences of rhetoric is crucial in order to avoid repeating past mistakes.

In-group loyalty and moral licensing can hinder self-reflection and accountability. Deliberation is essential in political discourse and should prioritize seeking truth over winning arguments.

Genuine disagreement and the ability to change one's mind are crucial for productive dialogue.

Cancel culture and the fear of being canceled can hinder open and honest deliberation.

Identity plays a significant role in shaping arguments, and recognizing this can lead to more understanding and reconciliation.

War-like rhetoric in politics can have serious consequences and should be approached with caution and thoughtful deliberation.

Sound Bites

"I'm interested in times that people talk themselves into unforced errors."

"Demagoguery first, and then you get a demagogue. They don't create it. They just ride the wave."

"Democracy is about people disagreeing. And so if you're going to say that people can't verbally disagree, then you're saying democracy can't function."

"Is it still demagoguery if it's boring?"

"Can deliberation be demagoguery if it's boring?"

"Democracy can be a casualty of rhetoric without deliberation."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 12, 2024

Robert Jenson's Last Interview

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

One of my regrets in life is that I did not seize the moment and forge a deeper relationship with the theologian Robert W. Jenson. Jens was in residence at the Center for Theological Inquiry when I was a student at Princeton Theological Seminary. I had started to read him in college at the suggestion of Eugene Rogers and David Bentley Hart, two of my first teachers. They had promised me that he was the best guide to ascend the mountain that is Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics. In the beginning, I understood Jens’s work well enough to be intimidated by his brilliance and concision. As a graduate student, I worked in the mailroom at Princeton and hand-delivered Jens’s mail every day to him at CTI. Despite such proximity, I only dared strike up a few conversations with him over the years.

One of my gratitudes is that Chris E.W. Green prodded me to go back and reread all of Jens’s work. As a more seasoned gospeler, as Jens would say, I have benefited anew from his attempts to say what we must say in order to say that Jesus lives with death behind him.

Another gratitude is that the podcast I share with friends was the last venue for an interview with Robert Jenson before he died in 2017. My friends Chris Green and Ken Tanner did the interview. Due to the nature of his Parkinson’s, Jens struggled with his speech and the audio requires patience on the part of the listener.

Thanks to Ken’s and Chris’s work we have been able to produce an accurate transcription of this last interview with Robert W. Jenson.

Spoiler:

He’s a universalist.

soli Deo gloria

Lift up your hearts unto the Lord. Heavenly Father, be with us in the coming days of trial. We thank you for whatever you have contributed to those days, to the work of Robert Jenson. He does not deserve the credit; you do. But we wish to thank you for it all the same. Amen.

Kenneth Tanner: Thinking back on your book, Conversations with Poppi about God—all those wonderful conversations you had with your then eight-year-old granddaughter, Solveig, where you talked at her level, trying to listen carefully to what she was asking, and responding with your characteristic humor—I asked a number of Holy Redeemer families if their children had questions they would like to ask you. And June, we call her Junebug, an elementary school student here in Michigan, sent me this question: “How is it that Jesus can see us but we can’t see him?”

Robert Jenson: Well, we can see Jesus. If we ask what the risen Christ looks like, the answer is, He looks exactly like that loaf of bread on the table and the cup of wine that goes with it. A living person looks like whatever he or she does at a particular juncture in his life. What does a human of two weeks gestation look like? Exactly like that fetus; that is that human being to be seen. By extension or analogy, we can ask what the risen Christ looks like and answer, He looks like that loaf of bread. The doctrine of transubstantiation in the Roman Catholic Church is devised to explicate that phenomenon. I don’t think it needs any explanation. But if you need one, you can try transubstantiation.

Chris Green: My son Clive, when he was three or four, asked his mom this question, which I’ll put to you now: When I get to heaven, do I tell Jesus or you when I have to go to the bathroom? I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about what we can expect of resurrection embodiment in the end—not only for Jesus, but also for ourselves.

Robert Jenson: At the very end, when the Lord comes in his glory, we will discover that the New Testament was very cautious about what it said. As to what damnation looks like, it’s very clear. But when it comes to the positive side of the final revelation, it turns to poetry. I have occasionally attempted to sum up that poetry by saying the final transformation of creation is into one vast implosion of love. What’s an implosion of love? In one way I don’t have the slightest idea… Nevertheless, it communicates. So the sum-up I have played with is “a vast implosion of love.” I have another sum-up that I play with and that’s to say, at the end of it all, the rest is music. A vast hymn, a three-part fugue played by God, with God, and involving us as variations on the theme. Does that help any at all?

Chris Green: Somewhere you talk about the bodily or sensual enjoyments we might enjoy. You ask if what the vintner practiced in this life won’t matter then. Maybe say something about that, the continuity between this life and the life to come.

Robert Jenson: You know, that question of the continuity is one of the vexed questions of all Christian theological history. I’m not sure that it’s solvable, short of being there in the end. We will be identifiable to each other, but how—I figure we’ll have to wait and find out. Dante, at the end of the vision of heaven, sees Beatrice—his beloved, whom he has sought through his life—as one of the members of the heavenly choir engaged in adoration of God. She leaves her place in the choir and comes to tell Dante what he’s seeing and hearing, and then she goes back. Is that the end of the love affair of Beatrice and Dante? It’s not altogether clear. In Dante, it looks a little bit too much that way for my taste.

Chris Green: Let’s talk about universalism for a moment. How has your mind changed on that over the years? Is everyone in the end included, brought into that vast implosion of love, or not? If so, how?

Robert Jenson: All the pressure of my theology, and I dare say of one stream of church theology (like in Gregory of Nyssa), presses toward universalism. Do I go over the boundary and say all will be saved? Karl Barth cautions against doing that, because of course there are passages in the New Testament that strongly suggest not. Sometimes, in a lightheaded mood, I have said, Well, sure, there’s hell; it’s just that there won’t be anybody in it. I guess I am a universalist. A great many other people in the present theological time are pressured the same way. Is that just a matter of fashion? Because theology does have fashions. I don’t know. I hope not. And maybe what we have is universal hope rather than universal knowledge.

Kenneth Tanner: One of my friends likes to say that there is a hell, but you have to fight your way through the love of God to get there.

Robert Jenson: Can you do that? Is the love of God ever finally defeated? I don’t think so. But that may just be because I live in the 21st century.

Chris Green: In one of our first conversations, I asked you a similar question and I told you that I was afraid of my own conviction. You said you were afraid too, for the reason you just described, afraid of being caught up in the spirit of the age and not the gospel.

Kenneth Tanner: I think you said, Chris, that if Jens were a universalist, he was one in fear and trembling.

Robert Jenson: Well, that’s me. And I guess I always have been. I don’t think my mind has ever changed. As soon as the question appeared in my consciousness, I went the one way.

Kenneth Tanner: Another question, this from a young woman named Catina: Why do some people not experience healing? Some people do and some people don’t.

Robert Jenson: Because that’s the will of the Lord. You know that I have Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disease. It isn’t reversible. Nevertheless, I pray to be healed. And one has to live with that. As to why there is so much suffering in the world, so much evil, that’s the famous theodicy question. And in my judgment, it’s the only good reason not to believe in God. If we nevertheless say, despite all the suffering in the world, God is good, that’s as far as we can go. There is no present available answer to the theodicy question, despite the fact that Leibniz thought there was.

Kenneth Tanner: Is part of the answer that God in Jesus Christ is with us and our suffering? He’s not standing outside of the human condition.

Robert Jenson: Oh yes, but why was it necessary for that to be the case? You just push the problem back one step. Look, the various answers proposed to the theodicy question may be of help in various contexts, but, to be slightly superficial, they don’t finally get God off the hook.

Kenneth Tanner: Reading your theology is not an exercise in scholarship; it’s an exercise in piety (to use a big word that people don’t use much anymore). As I’m reading, I’m involved in prayer. I wonder if you could answer that question, What is prayer?

Robert Jenson: Talking with God. Speaking up in the divine conversation. The Father and the Son in the Spirit are carrying on a great conversation, and as members of the body of Christ we are empowered and demanded to speak up in it. Our voices are very little, but they don’t count for nothing.

Kenneth Tanner: This gets to the question of change in God. Do we, by our prayers, affect change, the outcome of events?

Robert Jenson: Yes. I know that’s a drastic answer. But otherwise there’s no point in praying. At least not petitionary prayer. And the main part of Christian prayer is petitionary. The Lord’s Prayer is a series of petitions, so we can’t get off the hook by saying there are other kinds of prayer than petition. As Luther said shortly before he died, Wir sind bettler; hoc est verum. “We are beggars. That’s the truth.” And our begging is answered. Otherwise, why do it? I’m afraid that’s all I have to say on the question.

Chris Green: In your conversations with Solveig, she asks you about God’s motives. I’d love to hear you pick that up again all these years later. What motivates God—in creating at all, in saving us?

Robert Jenson: Since God is a communion, it is sort of natural to God—sort of natural—to desire to expand that communion. Solveig asked me the question, “Why isn’t he satisfied with Adam and Eve?” The answer I gave is, “Because he wanted to include Solveig.” I think that’s a pretty good answer still.

Kenneth Tanner: Yes, you say, “One way of saying what happened with Jesus is that Jesus so attached himself to you that if God the Father wants his son, Jesus, he has stuck with you too.”

Robert Jenson: That’s flippant, but correct. By the way, that’s Jonathan Edwards.

Kenneth Tanner: I would love to hear your fondest memory of Karl Barth.

Robert Jenson: Many people knew Barth much better than I ever did, but when I was in Basel for a short time, he was at the height of his fame. People traveled to Europe, eminent theologians and statesmen, and begged a short interview with the great theologian. I showed up one day as a student and said I was working on a dissertation about him and asked would he help me with it. He said yes. He was the most open, approachable person you can imagine to students. Unless you challenged him. Then he would switch gears and treat you as if you were Rudolph Bultmann incarnate or something, a debate in which all holds go. Both ways of acting showed his enormous respect for people. I guess my fondest memory of Barth is when Blanche and I were leaving Europe with the doctoral work behind us, and we traveled one more time down to Basel to say goodbye. It happened that it was the English Language Societate that was meeting, so the discussion was in English. The people there were mostly Reformed, and they tended to listen to Barth and say, “Ja, Herr Meister (Yes, Great Master),” and write it down. Blanche and I were sitting in the back, because we were just there to say goodbye. Finally, in frustration, Barth said something offensively not-Lutheran, and insisted, “Herr Jenson, What do you think about that?” And I was back into conversation again. That’s the last thing I like to remember. I snuck into the hospital room to say goodbye when he was obviously in his last illness. Marcus Barth tried to stop me but I managed to get in. He was unresponsive, so that’s not much of a memory.

Kenneth Tanner: That shows a great affection. And as Jesus said, when you visit the sick you visit me. I’m glad you made the effort. People know you as a theologian, but they can forget that you’re a pastor too.

Robert Jenson: Well, if that’s true, and I hesitate to say that it is, it’s a great honor that people think it. Thank you.

Kenneth Tanner: I certainly do. You’re a pastor to me. I wonder, what does Jonathan Edwards have to say to contemporary American Christians? You’ve said he’s “America’s theologian.” What do we need to hear from him right now?

Robert Jenson: That is a hard question. The book was written on the supposition that America was the nation founded by the Enlightenment and that Edwards was the one theologian who found ways to affirm the Enlightenment in a thoroughly Christian, Trinitarian fashion. The question is, Does the Enlightenment still mean anything to Americans? Or is that whole scenario that I painted overboard? The fact that many people, including Blanche and me, have not been able to vote for president because one party is committed to abortion on demand and the other party is committed to everything for the rich shows that we have arrived at some sort of a stalemate. Whether what we can get from Jonathan Edwards, or any other of those who have been idols in my theological life, will amount to something public, is a hard question. People refer to the Benedictine option in which the church commits itself to communities of its own that are dedicated to prayer and labor in hopes that simply the view of such a community can transform the rest of society. I don’t know. Maybe that’s it. You will understand that at this point in my theological life, I perhaps have more questions than answers, which may not be a bad thing.

Chris Green: What are some of those questions? What are the questions that you’re living with right now?

Robert Jenson: How to pray. All prayer is selfish. There’s no breaking that. And yet we are commanded to pray. So, I pipe up: Dear Lord, here’s what I think you should do. That’s an audacity past dreaming up.

Chris Green: Let me ask you about another great American theologian and what he has to say to us today. How should people be reading you right now?

Robert Jenson: For whatever they can get out of it. I’m not going to prescribe that. It never occurred to me when writing my systematics that people would find them passable. But you say you do. I’m delighted. Run with that. If they clear up intellectual questions, fine. If one essay of mine is bread cast on the water for anybody to pick up and be blessed by it, that justifies my whole effort. So I don’t have an answer to that question either.

Kenneth Tanner: The center of your systematics, of course, is Jesus. You say he is how we know God, period. Perhaps the most creative responder in America to your work is David Bentley Hart. I think it’s not too much to say that he reveres you, yet at the same time he finds some things challenging, particularly how you have approached the changelessness of God and the reality of Jesus. What would you say about the conversation that you’ve had with Dr. Hart?

Robert Jenson: Well, you know, in the book that made him famous, and in essays shortly thereafter, David praised me as some kind of marvel but insisted that at the key moment I had it exactly wrong. The villain of the history of Western theology, according to David, is Hegel. And he found my treating of the futurity of God to be too Hegelian. I’ve always protested that identification. There’s a way in which one can ask flippantly, Post Hegel, can anybody in Western theology be running with anything but some fragment of Hegel? And the answer to that is, No, probably. Am I Hegelian? Yeah, but so what? I don’t think that David finally comes out much different than Karl Barth. He would be the last person on Earth to agree with that, but I’m willing to venture it.

Chris Green: A lot of people, including Hart, accuse you of making God dependent upon history. You have insisted that that’s not true. Could you say again why it is not true that God is dependent on history?

Robert Jenson: It depends on what you mean by dependence. Would God be the God that he is if he had not ordained the history that he has? No, he would not. There’s the question, If God were not incarnate as Jesus, what would he be like? And I have, through most of my career, answered that he would obviously still be triune, but we can’t say anything about how. Lately, I have concluded that also the question is empty. It doesn’t mean a thing. Not only do I propose that there’s no answer to the question, What would God be like if there were not the history that he has ordained, I don’t think one can even ask that question. Not meaningfully. Does God suffer? Same question, finally. And the answer is, the Son of God suffers, but he does not suffer the fact that he suffers. His suffering is his own triumph.

Chris Green: Is that a difference between you and Motlmann?

Robert Jenson: I’m not sure. I have to say I’m not an expert on Moltmann.

Kenneth Tanner: The suffering that takes place is, in your theology, more about who is suffering than how (given the communication of idioms), no?

Robert Jenson: The second person of the Trinity is suffering. That’s dogma. Unus ex Trinitate mortuus est pro nobis. The qualifier, traditionally, is insofar as he is human he suffers. I prefer to say there is no way in which the Son is not human. So, the Son—as Son—suffers, but he does not suffer the fact that he suffers.

Kenneth Tanner: You and I were together with Wolfhart Pannenberg at a conference in Minneapolis in 1999, when he read a famous essay on the resurrection. Tell us about that relationship. How was Pannenberg meaningful for you?

Robert Jenson: When I got to Heidelberg as a naive graduate student, an American, I knew there were things I was going to have to know that I didn’t know. Being so naive, I thought I could just march up to a professor and ask if I could be a student. You weren’t supposed to do that. You were supposed to sit around in seminars until some professor noticed you. But I didn’t know that—so I got an appointment with Peter Brunner. The University of Heidelberg at that time didn’t print a catalog. Professors just tacked up on the bulletin board what they were going to do this particular semester. I knew the one thing I needed to know that I knew practically nothing about was 19th-century German theology. And here was a man named Pannenberg who was lecturing on Protestant theology in the 19th century. I went to Peter Brunner and asked if it would be a good idea for me to take that course. He answered, Well, Pannenberg is a very clever person. Perhaps a trifle too clever. I signed up for the course, and we never got past Schleiermacher. What I got from Pannenberg was the foundation of my knowledge of 19th century Protestant theology. So, I learned friendship, because we did become friends—and got one course, and one book: History as Revelation.

Kenneth Tanner: There are a lot of young pastors and young theologians who are reading you. I wonder if you have a word of encouragement for them in this particular moment, the young men and women who have dedicated themselves to the ministry of the church?

Robert Jenson: Thank you. Make of me what you will. If I inspire you, in any way, don’t thank me. Thank the Holy Spirit, and thank him on my behalf. That’s what I would say.

Kenneth Tanner: Would you pray for us?

Robert Jenson: The Lord be with you.

Kenneth Tanner: And with your spirit.

Robert Jenson: Lift up your hearts unto the Lord. Heavenly Father, be with us in the coming days of trial. We thank you for whatever you have contributed to those days, to the work of Robert Jenson. He does not deserve the credit; you do. But we wish to thank you for it all the same. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 11, 2024

As He Became Christ, So We Become Christians

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I am excited by the feedback I’ve received from some of you listening, viewing, and reading along with us.

Cd 221MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadShow Notes

If you’d like to join us on Mondays at 7:00 EST, the link is always THIS.

And here is the PDF of Barth’s Church Dogmatics: II.2.

Summary

In this conversation, the hosts discuss the concept of election and predestination from Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics. They explore how Bart rejects the idea of an arbitrary and predetermined list of who goes to heaven and who goes to hell. Instead, Bart emphasizes that election is rooted in the person of Jesus Christ, who chose to come to earth as both fully God and fully human. The hosts also discuss the implications of election, including the idea that Jesus' election is specifically his election to suffer, and that his suffering is the basic act of divine election. They emphasize that election is a personal and relational concept, and that being in Christ means being fully known and loved by him. The conversation also touches on the topics of universalism and the participatory dimension of election.

Takeaways

Election is not an arbitrary and predetermined list, but is rooted in the person of Jesus Christ.

Jesus' election is specifically his election to suffer, and his suffering is the basic act of divine election.

Being in Christ means being fully known and loved by him.

Election is a personal and relational concept, and emphasizes the constant and unconditional love of God.

The concept of universalism should not be confused with the personal and relational nature of election.

Sound Bites

"God's love is always freeing and so people should never live under the myth that they are in any way stopped by God's absolute love for them."

"Election has all of that throbbing aliveness to it. It's the voice of Jesus who's saying, 'Come to me, all you who are weary and heavy laden, and I will give you rest.'"

"The nature of universalism is to say that people have to respond in a particular way, which is what your people are saying. Well, then they have to go to heaven or something like that. The nature of universalism ism -ness of it makes it a system. It removes it from a personal dynamic."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 10, 2024

“I Don’t Know if God is the Devil or the Devil is God.”

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

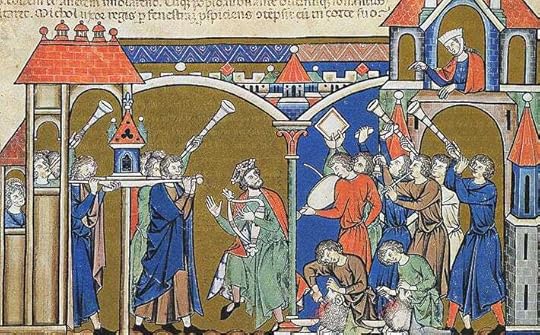

The lectionary this Sunday excises from 2 Samuel 6 the story of the Lord striking Uzzah dead merely for touching the ark of the covenant.

Rather than protect the church from the God of this passage, the church should instead point to the God who clothes himself in Christ. That is, the story of Uzzah’s unfortunate demise gets to the heart of Luther’s distinction between the Unpreached God and the Preached God.

My friend Ken Jones has a relevant passage on Luther’s distinction from his wonderful book.

The problem with philosophical proofs for God is that once you get yourself a provable God, it leaves way bigger questions standing there: If this God exists, how do you know who that God is? Is this God actually good? In the end, what will God’s judgment on you be?

All the questions and proofs force a difficult realization on you: using your senses and your rational mind, you can’t truly know anything about God’s existence, actions, or attitudes toward you.

And you wind up with my Twin Bed Theological Terrors.

If you try to suss it out by looking at the world around you, you might say you have found evidence in nature. The breathtaking beauty of a sunset, a rainbow, the variety of snowflakes and human faces, and the way harmony works in music—all these things show us both God’s existence and his goodness. You can add plenty more to the list from your own experience, from the taste of ripe strawberries, to rumbling thunder, to the twinkling of a field of stars on a summer’s night or that of your beloved’s eyes. Yet it is not hard to find other scientific explanations for all these things that say nothing at all about God.

What’s more, if you want to use beautiful and amazing things as proof of God’s existence or goodness, you also have to take with them all the bad things you see and experience in nature: natural disasters, cancer, the perils of toilet training, adolescent angst, and all those things insurance companies call “acts of God.”

Even if you could argue for God’s existence, when you add these things to the mix, it becomes hard to say whether God is even good. Luther said this was the greatest temptation.

Like Luther, you can get to the point where you say you “don’t know if God is the devil or the devil is God.”And in our game of divine Sardines, God remains tucked away in some inaccessible eternal nook. That is the exact confusion that crops up in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 3. The temptation the serpent sets before the woman is not whether she and the man should eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Instead, the serpent asks whether they can trust God’s motives in commanding them to keep away from the tree and God’s judgment of death. The serpent says, “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:4b–5).

Instead of trusting God to give them all that they needed for their creaturely existence, they turned to the serpent for its wisdom and to themselves as agents for concocting their future. They came to think that God was holding back something especially good. At best, they regarded God as their lackey and, at worst, their enemy. Thus our first parents and every generation after them have taken matters into their own hands. That’s what happens when God remains hidden behind the veil, when you can’t grasp what God is up to, and when the threats and temptations of this world move you to seek certainty. You scramble to cobble together something sure.

Luther knew something of such things when he wrote his explanation of the first article of the Apostles’ Creed in the Small Catechism in 1529:

I believe that God has created me together with all that exists. God has given me and still preserves my body and soul: eyes, ears, and all limbs and senses; reason and all mental faculties. In addition, God daily and abundantly provides shoes and clothing, food and drink, house and farm, spouse and children, fields, livestock, and all property—along with all the necessities and nourishment for this body and life. God protects me against all danger and shields and preserves me from all evil. And all this is done out of pure, fatherly, and divine goodness and mercy, without any merit or worthiness of mine at all!

This is nothing like the vast, terrifying power of a God who remains hidden. Luther came to know a God who is gracious, patient, and lavish in bestowing gifts. In fact, he argued that you could come to see God in creation, even in the hard facts of life and the terror of nature’s perils.

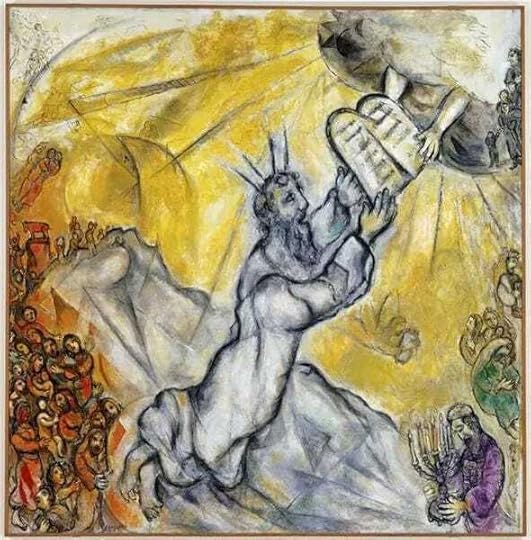

You could come to regard all these things as simple masks covering the face of God.In the Old Testament, seeing God without a mask is a dangerous thing.When Moses and God’s people were enslaved in Egypt and Pharaoh finally released them from bondage, they stood trapped at the sea with the Egyptian armies, with all their horses and charioteers, coming up behind them. God appeared behind the masks of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. But when God gave the enemy armies a glimpse of divine might and glory, they were thrown into a panic. Their chariots were stuck, and people fled hither and yon—all from a wee glimpse behind the veil.

Later, when Moses was given the commandments on Mount Sinai, the mountain was clouded over, and the people below were protected from God’s nearness. When Moses said to God, “Show me your glory,” God said to Moses, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live” (Exodus 33:18–20). Moses was instructed to hide in a crack in the face of the rock, and Moses had to wait until God said “when.” The most Moses was allowed to see was God’s back, but still, when he came down from the mountain, Moses had been physically changed: “The skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God” (Exodus 34:29).

Looking at the guy who had looked at God so spooked the Israelites that from that time forward, Moses took the clouded Mount Sinai as his model: he wore a veil over his head and only took it off when he went back to the summit to chat with the Lord.

The commandment-inscribed tablets that God gave Moses were placed in a golden ark, which was carried with the Israelites in their wilderness wanderings and in their conquest of the land God had promised them. The ark that contained these tablets that God’s own hand had touched was so holy and so dangerous that when the Israelites moved their encampment, only the priests could come close, and the rest of the people were instructed to stay 1,000 yards away from it (Joshua 3:4). Years later, when the ark was being moved on an oxcart, the holy crate began to slip. A man named Uzzah reached out to steady it, and—Zap! Learn your lesson, Uzzah!—he was struck dead on the spot. King David heard of these things and was afraid to have the ark anywhere near him (1 Chronicles 13:9–14). When the temple was finally built in Jerusalem, the ark was installed in a space with floor-to- ceiling curtains surrounding it. The space was called the Holy of Holies, another way of saying it was the holiest of spaces. Ever. No one was allowed to enter except the high priest, and he could only do it on the Day of Atonement.

In the 1981 Steven Spielberg blockbuster, Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazi villains and the hero, Indiana Jones, are on a race to capture the Ark of the Covenant. The Nazis hope to harness its powers and use God as a weapon for Hitler and the Third Reich. At the climax of the movie, Indy and his companion Marion are themselves captured and bound while the Nazis intone the ancient words of the Israelite priests. As the villains lift the lid of the ark, Indy says, “Shut your eyes, Marion. Don’t look at it, no matter what happens.” The villains come to their end when the power and glory of God rise out of the ark and cause wholesale destruction: lightning-fried soldiers, melting faces, and exploding Nazi heads. But the protagonists are saved because they didn’t look or come near.

Of course, Raiders is a fiction, but in at least one way, it tells the truth.

Be careful about wanting to see an unhidden God.Even encountering God secondhand is dangerous stuff, and God will brook no attempts to get behind the veil. You won’t get to crawl into God’s hiding space and have other seekers cram in with you. The game of divine Sardines can’t end. You’re left to wander, grumpy and frustrated, and wonder what kind of God this is. You’ll say, “Hidden God? No thanks. I’ll stick with something I can see and trust.” And that’s where Article I of the Augsburg Confession is in your corner. By including the language of the Holy Trinity (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), Philip Melanchthon points to the places God wants to be encountered and where faith can actually see God. And it gets even more specific. The article speaks of who Jesus is: both completely divine and wholly human.

That means that in this person, Jesus of Nazareth, you have access to a God who is overflowing with loving kindness for broken and sinful human creatures.It means that God has determined to call everyone in from hiding, “Olly olly oxen free.” Or as Paul said in Galatians, “For freedom Christ has set us free”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 9, 2024

Luther and the Gospel

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

I’ve recently begun a lectio continua sermon series through Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. Returning to Paul’s letters, I recalled that the Minion and I had offered an online class on Luther and the Gospel during the shuttered days of the pandemic. Together we read important, short texts like The Freedom of a Christian, Preface to the New Testament, The Gospel as Sacrament, and What to Look for in the Gospels.

From the vault, here is the second session.

And just a few years has made possible the AI-generated show notes below.

Show NotesSummary

Last week, the conversation focused on the paradox of the Christian life, derived from Christ's condescension into the flesh. Luther believed that the meaning of the Christian life could be derived from the meaning of Christ's condescension. Righteousness, for Luther, is not intrinsic to us but is something that pertains strictly to Christ himself and is given to us through faith. The conversation also touched on the division of scripture into law and gospel, with Luther emphasizing that the purpose of commands in scripture is to reveal our unrighteousness and lead us to turn to the one who has saved us. The outer person section discussed how works flow from faith and are a privilege rather than an obligation. Luther compared our status as people of faith to Adam and Eve in the garden, where they had a vocation and no requirements for justification. Luther encouraged living in accordance with our vocation and being the creatures we were made to be. In this part of the conversation, the hosts discuss the difference between Luther's view on virtue and the traditional views of Aristotle and the Church. Luther believes that a good person does good works because they are already righteous in the eyes of God, whereas Aristotle believes that virtue is acquired through habit. Luther emphasizes the imputation of righteousness before all else and the importance of understanding the gospel correctly. The hosts also discuss the connection between baptism and faith, with Luther believing that baptism is the outward visible sign of God's claim on a person. They address the difference between love for a neighbor by a believer and a non-believer, with the believer understanding that it is an operation of the Spirit. They also touch on the idea that God appreciates good works by non-believers, but wants them to know that it is Him working through them. The conversation concludes with a prayer.

Keywordsparadox, Christian life, righteousness, Christ's condescension, law and gospel, commands and promises, works, faith, Adam and Eve, vocation, Luther, Aristotle, virtue, righteousness, gospel, baptism, faith, love, good works

Takeaways

The Christian life is a paradox, derived from Christ's condescension into the flesh.

Righteousness is not intrinsic to us but is given to us through faith in Christ.

Commands in scripture reveal our unrighteousness and lead us to turn to the one who has saved us.

Works flow from faith and are a privilege rather than an obligation.

Living in accordance with our vocation allows us to be the creatures we were made to be. Luther's view on virtue differs from Aristotle and the Church, as he believes that good works are a result of already being righteous in the eyes of God.

Baptism is seen as the outward visible sign of God's claim on a person, and it is not dependent on the person's faith or actions.

The difference between love for a neighbor by a believer and a non-believer lies in the believer's understanding that it is an operation of the Spirit.

God appreciates good works by non-believers, but wants them to recognize that it is Him working through them.

Understanding the gospel correctly is crucial for being a doer of good works.

Sound Bites

"The paradox of the Christian life, namely that we live in a manner that is both truly God and truly human."

"Righteousness is no thing except for what Christ offers us."

"The purpose of commands in scripture is to reveal to you just how unrighteous you are so that you have no other recourse but to turn to the one who has saved you."

"A good person does good works."

"You learn how to be good from Christ."

"The importance of rightly understanding the gospel as the necessary predicate to being a doer of good works."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 8, 2024

"The Lectionary is Designed to Protect the Church from Idiot Preachers"

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

2 Samuel 6:1-5, 12b-19

A dead horse I routinely beat is the deficiencies of the lectionary, the three-year cycle of scripture readings assigned for the liturgical calendar.

The version most widely used by mainline Protestants is the Revised Common Lectionary. For each Sunday, the RCL assigns an Old Testament reading (except when it doesn’t), a Psalm, an Epistle or, on dashingly rare occasions, a reading from Revelation, and finally a Gospel reading. As it’s a three-year cycle, Matthew, Mark, and Luke receive emphasis accordingly. The Gospel of John meanwhile gets treated piecemeal, which is unfortunate given that John, more so than the Synoptic Gospels, stands apart as demanding sustained attention to its high Christology and nuanced narrative.

As a professor at Princeton once griped to our class, “The lectionary is designed to protect the church from idiot preachers.”

I have as many problems with the lectionary as the lectionary has Sundays devoted to John 6. Seriously, Year B has five Sundays devoted to John’s account of Jesus’s sandwich powers.

Among the reasons I think the lectionary sucks:

The lectionary consistently treats Old Testament passages as proof-texts for the paired New Testament readings. Thus, the lectionary unsubtly conveys that the Old Testament is but historical background material for understanding the New Testament. The Old Testament is fulfilled by the New rather than authoritative in its own right. This is not how the Old Testament functioned for the early church. What we now call the Old Testament was the only scripture known to and authoritative for the apostles. Accordingly, the New Testament has a different, more provisional authority than the Old Testament. Whereas the scriptures of Israel were the unquestioned Bible of Mary’s boy and so authoritative, the New Testament canon came together under emergency duress. Now however, to the extent preachers even deal with the Old Testament texts, the lectionary’s pairings tempt preachers to commit one of two heresies, Marcionism (positing that the God of the Old Testament is not the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ) or Supercessionism (presenting the church as having supplanted synagogue in God’s purposes).

If you think the above point is hyperbolic, then consider the next reason I believe the lectionary sucks. During the season of Eastertide, the New Testament Book of Acts replaces readings from the Old Testament. Not only does this again encourage supercessionist readings of scripture, it obscures the fact that resurrection is a Jewish belief. Is it any wonder, then, that church people routinely still make cringey comments about Jews?

The Gospel passages assigned across all three years consistently privilege moments from the ministry of Jesus rather than to the Passion of Christ. You may have noticed that this is exactly the reverse of how the Gospels themselves weight their narratives. We should not surprised, then, that so much of the preaching in the churches is Glawspel, moralism in Jesus drag.

The lectionary leaves out approximately three-quarters of the Bible. I am not exaggerating. Over three years the church hears only a fourth of the scriptures, all of which— the dogma claims— are inspired by God, passages he has promised to pass through if we but sit and wait.

Much of what the lectionary leaves out are the Bible’s women. The Protestant Church does not simply have a Mary problem. We neglect all her sisters. Among the ladies left out by the lectionary: Dinah, both Tamars, Rahab, Achsah, the daughters of Zelophehad, Jael, Jephthah’s daughter, the Levite’s concubine, Rizpah, Abigail, Michal, Merab, the Shunammite woman, Huldah, Priscilla, Philip’s four prophetess daughters, Phoebe, Junia, Tryphaena, Tryphosa, Persis, Julia, and the elect lady of II John. As my friend Sarah Hinlicky Wilson notes, in Matthew’s year, lectionary leaves out the story about the woman who anointed Jesus’ feet, of which Jesus (ironically) said, “Wherever this gospel is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will also be told in memory of her.”

Something else with which the lectionary fails to trust the church and her preachers, the troublesome texts of scripture and its themes of judgment and wrath, the latter’s absence can account for the prominence in the church’s preaching of Moral Exemplar interpretations of the atonement. That is, Jesus’s death on the cross does not satisfy, propitiate, rectify, or deliver. On the cross, Jesus merely models for us selfless, self-sacrificing love that in turn moves our hearts to turn from our sin.

Exhibit A:

This coming Sunday’s Old Testament passage is— catch the verse notation— 2 Samuel 6:1-5, 12b-19.

Whenever the lectionary skips over seven verses and chops another in half (12b), you can be certain the story is one that Roald Dahl would love.

What does the lectionary attempt to protect the church from this Sunday?The unfortunate story of Uzzah that interrupts King David dancing before the ark of God:When they came to the threshing floor of Nacon, Uzzah reached out his hand to the ark of God and took hold of it, for the oxen shook it. The anger of the Lord was kindled against Uzzah; and God struck him there because he reached out his hand to the ark; and he died there beside the ark of God. David was angry because the Lord had burst forth with an outburst upon Uzzah; so that place is called Perez-uzzah, to this day. David was afraid of the Lord that day; he said, “How can the ark of the Lord come into my care?” So David was unwilling to take the ark of the Lord into his care in the city of David; instead David took it to the house of Obed-edom the Gittite. The ark of the Lord remained in the house of Obed-edom the Gittite three months; and the Lord blessed Obed-edom and all his household.

When approaching a disquieting passage like 2 Samuel 6, the reader should remember the assertion in Hebrews 4.2 (and this is also a text the lectionary leaves out):

"The word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.”

In other words, according to the author of Hebrews, the word does not record; the word works surgery upon us.

The word does not record.

The word works surgery upon us.

Scripture is not a tale of what God did. Scripture is the tool with which God does.In his book On the Inspiration of Scripture, the theologian Robert Jenson points to the many medieval paintings which show the Holy Spirit hovering beyond a biblical writer as he puts his witness to the page to compose the canon.

It is our tendency to think of the Spirit’s relation to the scriptures as extrinsic— outside of us— and historic— back before us— that is the chief error that has distorted the church’s understanding of the inspiration of scripture.

“The pictures that show the moment of inspiration as the Spirit bending over a busily writing prophet or apostle,” Jenson writes, “depict the wrong scene altogether.”

Because, of course, as we acknowledge at every baptism and in every prayer meeting, “the mighty acts of God” go on today.

The apostolic church enjoys no advantage over us in terms of the Spirit’s activity.To make it plain:

The scriptures were not inspired by the Spirit.

The Spirit inspires the scriptures.

The Spirit inspires with the scriptures.

The doctrine of inspiration does not mean that the Bible is a record of reliable information about God. Of course that’s not what it means— rabbits don’t chew the cud, as the Book of Leviticus seems to think.

The doctrine of inspiration does not mean that the Bible is a record of reliable information about God.The doctrine of inspiration means that the Bible is the reliable way God acts savingly in our lives.The correct picture of scripture’s inspired nature is not the picture that shows the Spirit bending over the narrator of 1 Kings or Paul as he writes to the church in Corinth. The correct picture is, well, you and me, waiting like Moses in the cleft of the rock, for the Lord to pass through a passage of scripture: “May the words of my mouth and the meditation of all our hearts be your living word…”

Just so—