Jason Micheli's Blog, page 19

February 10, 2025

"Somebody Has to Say Such Things!"

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Become a paid subscriber!

The assigned lectionary passages for this coming Sunday provide a reminder that the word of God makes alive only because, in the first instance, it kills. Thus, the scriptures for the Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany meet us in our cultural moment and do their mortifying work:

“Cursed are those who trust in mere mortals.”

— Jeremiah 17

“Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked or take the path that sinners tread or sit in the seat of scoffers.”

— Psalm 1

“If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.”

— 1 Corinthians 15

“Woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry. Woe to you who are laughing now, for you will mourn and weep. Woe to you when all speak well of you, for that is how their ancestors treated the false prophets."

— Luke 6

As the preacher Nathan says to King David so these scriptures likewise indict many of us, “You are the man!”

Paul’s argument to the church at Corinth is the lynchpin in the series of passages, for if resurrection is hope, then the apostle rightly identifies sin as despair; in that, nihilism is the necessary predicate to tread boldly the path of the wicked and sit in league with scoffers.

February 9, 2025

I AM Finished

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Psalm 23

I was sitting in the waiting room at my oncologist’s office, an imposing volume of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics on my lap. Even at my age, on almost every visit, I’m the youngest person in the waiting room— a point of irritation which I often express to the Lord with less than sanctified language. But this week, an Indian family sat across from me, a middle-aged husband and wife. Their daughter, no higher than my elbow, was snuggled in between them. The little girl’s eyes looked hollow with exhaustion, her once tan skin appeared almost translucent, and her dark hair already nearly as thin as mine.

She looked like a shadow version of herself.

I don’t know her prognosis, but death has her in its sights.

As the mother brushed the girl’s hair with her hand and whispered assurance into her daughter’s ear, I noticed a silver cross hung from her neck and lay draped against her blouse. For her part, the girl calmly looked at the glossy pictures of far away places in a wrinkled back issue of a travel magazine. When a nurse with a clipboard called the family’s last name, they stood up and gathered their things.

“Good luck,” I said to them.

I’d only meant by it a show of camaraderie, like we’ve all been drafted as teammates for a sport none of us wants to play.

“Luck?” the girl’s mother said like she hadn’t heard me right.

I nodded and gestured to the infusion lab, “Good luck.”

The mother shook her head with a look. It was just shy of disdain— surprise, I’d say. She glanced at the book on my lap and then looked at me, as if wondering why anyone would read such a book— Church Dogmatics— if they were not a believer.

“Good luck,” I said again, thinking maybe their English was the problem, “This can be a scary place.”

This time the girl’s father shook his head.

“Why would we need luck when we have Jesus? He is with us. This is not scary at all.”

I’ve got a pretty good acute bullshit meter. I could tell from his tone of voice that he was not simply saying it for his daughter’s sake. He truly believed it. And with his arm around his little girl, rendered rail thin by cancer, they walked into the infusion lab as though it was God’s heaven.

Though it happens not in a valley but in the wilderness of Horesh, when King Saul plots to kill his usurper, David does indeed fear evil. Despite the LORD himself speaking a promise of safety to David, David hides in a desert stronghold in Ziph. The Shepherd's rod and crook do not always offer David comfort. On the contrary, with Saul’s troops in vengeful pursuit of him, dread and panic fall like shadows over David. The specter of death does in fact compel David to fear.

Just so, a question:

Is David less faithful than the father of the cancer-stricken girl?

Is King David less consistent in his confidence in the LORD than a middle-aged father in khakis and a cable-knit sweater?

How is that dad different from David?

Five years ago next month, the New York Times ran a story about the chaplains— rabbis and pastors and priests— rushing to care for the sick and the dying in hospitals overrun by the COVID- contagion. Chaplains told the reporter that the Covid-19 pandemic was unlike anything they had seen before in the intensity of the sickness, the speed at which it could lay a person low, and the sheer number of deaths.

A chaplain in Seattle, Rev. Leah Klug recalled performing an anointing of the sick with mouthwash, because she didn’t have any oil on hand. At patients’ request, she often read the twenty-third psalm above the steady beep of a heart monitor. “So many want to hear, “The LORD is my shepherd,” she told the Times.

Chaplain Walker, a veteran of the Persian Gulf, told the reporter that the pandemic reminded him of serving in the Iraq War — “except,” he said, “I’m closer to Death now than I was on the very front lines of combat…Yesterday I was told, “Go to this unit — they had four deaths.” Then it was, “Go to this unit — they had three deaths.””

“It’s not just that they’re working flat-out,” a nurse commented on the chaplains’ work, “It’s that they are working flat-out, in the shadow of death, knowing that doing so puts them and their own families at risk.” “We are walking in the valley of the shadow of death, along with our patients and their families,” said the Rev. Katherine GrayBuck, a chaplain in Seattle.

“Few run towards the dying. Even fewer run towards the contagious,” Chaplain Walker observed. “It is not natural to go racing toward someone or something that is trying to kill you. It is not natural not to fear death.”

Why were those chaplains all able to practice a constancy of confidence in the face of death that King David could not reliably muster? Why were ordinary priests and pastors in 2020 less afraid of death than the LORD’s own chosen and anointed king in 885 BC? After all, the David who professes his freedom from the fear of death in Psalm 23 is the same David who elsewhere claims otherwise.

David himself contradicts the confidence at the heart of this prayer:

“My heart is in anguish within me; the terrors of death have fallen upon me. Fear and trembling come upon me, and horror overwhelms me. And I say, “Oh, that I had wings like a dove! I would fly away…”

Once again—

Why were hospital chaplains able to embody this psalm better than the one who first prayed it?

Etty Hillesum was a Jew who was only twenty-nine years old when she was first deported from the Netherlands and later murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp. A law student, Hillesum had been raised in a chaotic and secular home. To the consternation of her friends, Etty Hillesum refused to go into hiding when the roundup of Jews escalated in 1942. On July 5, 1943 the occupying German army deported her first to the Westerbork transit camp and eventually to Auschwitz where she died five months later.

During those twenty weeks of the holocaust, Etty Hillesum encountered God for the first time— an overpowering and mystical experience she recounted in her diary. When she and her family were forced onto a train from the Netherlands to Auschwitz in September of 1943, Hillesum quickly wrote these lines on a postcard and threw it from the train to be recovered, “The Lord is my high tower. In the end, the departure came without warning…We left the camp singing…Thank you, Lord, for all your kindness and care.”

As she prays to God from the Westerbork concentration camp— deep in the valley of the shadow of death— Hillesum nevertheless perceives the prison as a place of beauty, its darkness illumined by the love that is God.

She writes:

“All I want to say is this: The misery here in the concentration camp is quite terrible; and yet, late at night when the day has slunk away into the depths behind me, I often walk with a spring in my step along the barbed wire…And then time and again, it soars straight from my heart—I can’t help it, that’s just the way it is, like some elementary force—the feeling that life is glorious and magnificent, and that one day we shall receive a whole new world.”

Etty Hillesum’s family did not survive transit from the Westerbork camp to Auschwitz, yet their deaths did not leave her alone. One of her last journal entries before she was led to the gas chamber is a prayer:

“You have made me so rich, oh God, please let me share out Your beauty with open hands. My life has become an uninterrupted dialogue with You, oh God. Sometimes when I stand in some corner of the camp, my feet planted on your earth, my eyes raised toward your Heavens, tears sometimes run down my face, tears of deep emotion and gratitude. At night, too, when I lie in bed and rest in you, oh God, tears of gratitude run down my face, and that is my prayer.”

Again—

How is it possible that a Dutch Jew performed this psalm more fully than David who prayed it?

According to the ancient rabbis, it was after Saul first attempted to murder David, hurling a spear at him as he played the lyre, that David uttered another prayer in contradiction to the confidence of Psalm 23. David eludes the killing blow. Saul drives his spear into the wall. On his wife’s advice, David flees for his life. And as he escapes, from that place of deep darkness so say the rabbis, David prays, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The Cry of Desolation begins the psalm just before David prays, “Yea, though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil, for you are with me.”

Why was Etty Hillesum at Auschwitz able to embody that prayer better than David of Bethlehem? How was she free from fear in a way that David, despite his words, was not? That is, how did Psalm 23 transfigure from prayer into promise?

Or rather, what happened to death?After all, it is not natural not to fear death. So what happened? In between David and that dad at the oncologist’s office, in between David and those COVID-19 chaplains, in between David and Auschwitz, what happened?

What happened to death?

What was done to death?

Shortly before the bishop appointed me to Annandale, I conducted a funeral for a boy at my youngest son’s elementary school. Named after King David’s best friend, Jonathan was in the fifth grade when doctors discovered the cause of his persistent headaches and blurred vision. The oldest of his four siblings, his parents had immigrated here from the Ivory Coast when Jonathan was a baby. On the night he died, I accompanied the school principal to his hospital room to anoint him, to hand over the absolution, and to pray with his family. Jonathan’s mother had arranged the pictures his classmates had painted for him so that they ringed all around his body like the halo that encircles Our Lady of Guadelupe.

At his mother’s request, we prayed the twenty-third psalm.

The final words, “…the house of the Lord forever…,” were still tumbling out of my mouth when Jonathan’s little brother let go of my hand and tugged on the sleeve of my clerical shirt.

He even raised his hand like we were at school.

I knelt down to look him in the eye.

“Yes,” I said softly.

“Um, can I ask a question?”

“Of course. What’s on your mind?”

“Why did God make dying? Why did God make dying?”

In the Gospel of John, in the very same discourse in which the Lamb of God announces that he is simultaneously our Good Shepherd— that is, he is both one of us, a member of the flock, and God— Jesus makes it explicit that he is the active agent of his looming passion.“I lay down my life,” Jesus declares, “No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it up again.”

In other words—

Dying is not something that happened to Jesus.Dying is something he did.Dying was his deed.“Consummatum est,” Jesus proclaims upon the cross, “It is finished.”But again since Jesus is not the passive victim of his passion, his sixth word from the cross is better conjugated in the active voice, “I am finished.”Dying is not something that happened to Jesus.Jesus is what happened to death.The apostle Paul calls death God’s final enemy. Death is God’s ultimate enemy because it is the annulment of the life God made for his creatures. But enemies, Jesus teaches, are to be reconciled. Just so, when the crucified and risen Christ lays his right hand on John of Patmos and declares, “Fear not, I am the first and the last, and the living one. I died, and behold I am alive forevermore, and I have the keys of death,” Jesus holds those keys because he has made even death his home. By becoming incarnate, God makes every nook and cranny of his creation his domain— even death.

I am finished.

Jesus is what happened to death.

Jesus is what God did to death.

The cross judges all, yes— of course. But judgement and sin are only partial aspects of the gospel. Even more so, Christ’s death heals everyone and everything— crux est mundi medicina. As the church father Gregory of Nazianzus put it, “That which is not assumed is not healed.” Therefore, what is assumed is healed, including, especially, death.

Just as in stepping into the Jordan River Jesus sanctifies the water for our own baptisms, so too in descending into suffering and death Jesus hallows them. He made them places where he can be found. He claimed even death for God.

This is the straightforward claim of the scriptures:

“When Christ ascended on high he led a host of captives (suffering and death) and he gave gifts to men. In saying, “He ascended,” what does it mean but that Christ had also descended into the lower regions of the earth (the grave)? He who descended is the one who also ascended far above all the heavens, in order that he might fill all things with himself.”

In other words, Jesus took captivity captive. As Maximus the Confessor writes, “Christ died to convert the use of death, reworking it into the condemnation of sin but not of nature, making death an end of all that is inhumane and ungodly, changing death from a weapon to destroy human nature into a weapon to destroy sin.”

Christ converted death.

This is what the apostle Paul means when he addresses the church at Corinth:

“The Father of all mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. For as we share abundantly in Christ's sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too.”

That is, because God died, God’s creatures can die otherwise. Jesus is what God did to death. Jesus is what happened in between David and Etty and all the rest.

And take note—

Jesus did not make death good.Jesus made it an access to God who is Good.Thus, as Maximus insists: Christians weep at death; we marvel at Christ.

On her plank bed in an overcrowded barracks, Etty Hillesum prayed:

“Dear God, these are anxious times. Tonight for the first time I lay in the dark with burning eyes as scene after scene of human suffering passed before me. But no one is in their clutches who is in your arms, God. I shall never drive You from my presence.”

You are with me.

Jesus made her prayer possible.

“Why did God make dying?” David—his name is David— asked me.

I put my hands on his tiny shoulders.

“God did not make dying,” I said, “God made only living. God wants nothing for us but good.”

He stared at me, sensing the incongruity of my words with our location.

“God died,” I added, “so that, even in his dying, Jonathan is not alone.”

Just then, his mother looked up from the bed. She blew her nose and nodded and laughed a little.

“So it’s not just me,” she said, “That’s why I feel Jesus here with us.”

“Yes,” I said.

“Can I talk to him?” David asked.

“To your brother?” I asked.

“No, to Jesus.”

“Sure. Of course.”

But he didn’t pray, exactly. The second grader sat down on the chair next to his brother’s bed and he simply started a conversation with someone only the eyes of faith can see.

In the Gospel of Luke, as Jesus nears his dying, he laments over Jerusalem, weeping, “How often would I have gathered your children together as a mother hen gathers her brood under her wings.” The image is a popular icon of the church. But the image of a mother hen with her chicks protected beneath her wings is only the second half of the complete picture. It’s part of Jesus’ response to the Pharisees’ alert that King Herod aims to kill him. Just before the verse about the mother hen and her brood, Jesus responds to the Pharisees, saying, “Go and tell that fox for me, “Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work.”

You see the sequence?

Herod and the forces of death are a fox.

Jesus is a mother hen.

We are the brood sheltered beneath him.

Jesus outfoxes the fox.

Even in death’s belly, we are sheltered underneath Christ’s wings.

Thou art with me.

Jesus did not make death good.Jesus made it so that God is at work even on the insides of death.I am finished.

Not long before he died, the theologian Robert Jenson delivered a funeral homily upon the death of his friend John.

In the sermon’s conclusion, Jenson preached:

“In scripture, death is never seen as a good thing by itself. Rather, it is always portrayed as God’s great antagonist. Death is the enemy of love; and God is love. John was a loving man, and now we all lack that love. Despite all our efforts to hide from death, or explain it away, or say that it’s only natural after all, death by itself remains an unfathomable evil. Indeed, only by looking to one particular death, to Christ’s death on the cross, can we grasp it at all.

Christianity simply is the faith that the Lord raised him from the tomb to which we consigned him. Death by itself is indeed an unmitigated evil, but it turns out that death is not by itself. Christ lives as the one with that “and" there.

He is for all, for all eternity, Christ crucified and risen.

And that means—among much else—that we can, putting it crudely, relax a little in this life, lay back a bit. If the worst, the shadow of death, must give way to the best, to life in God, what else could there be to fear? Because Christ lives, we can be a little at ease in this troubled and dangerous world…There are, I suppose two ways of relaxing in the world.

One is to think that nothing is worth caring about, so why worry?

The other is to think—with John—that everyone and everything is worth caring about, and that we dare do that because Christ lives.”

Though in Psalm 23 he claimed otherwise, David was no stranger to the fear of death. But of course David was afraid in the valley of the shadow of death. The LORD had not yet done Jesus to death. Therefore, despite his great faith and his heart after God’s own heart, David lacked what you and I possess— just four little words, “Christ is risen indeed.”

So relax.

Lay back a bit.

And amble on up to the table.

Because our Mother Hen lives, he not only shelters us in his wings but feeds us. Because he lives, the loaf and the cup, the bread and the wine— they are “sacraments of death’s demise.”

So take and eat.

And dare to care.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 6, 2025

God Loves Being Our God-- Convey It

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

It has been my privilege to be the Preacher-in-Residence for the Iowa Preachers Project. In addition to our quarterly in-person gatherings, the cohort meets monthly online to discuss aspects of the proclamatory task.

Here is a conversation I had with them.

Summary

This conversation delves into the intricacies of preaching, focusing on the speaker's personal process, the role of commentaries, the decision to move away from the lectionary, and the importance of context in sermons. It also addresses the challenges of preaching in a politically charged environment and offers insights for new preachers on defining the gospel and developing their unique voice. In this conversation, the speakers delve into the complexities of preaching, discussing the challenges they face, the importance of vulnerability, and the role of personal stories in engaging sermons. They explore the balance between sharing personal experiences and maintaining the focus on the message, as well as the process of sermon preparation and the integration of life experiences into preaching.

Takeaways

Preaching requires a deep engagement with scripture and context.

Moving away from the lectionary allows for deeper exploration of biblical texts.

Commentaries can sometimes limit a preacher's ability to read scripture Christologically.

The gospel is fundamentally a promise based on the resurrection of Jesus.

Preachers must navigate political contexts with sensitivity and awareness.

Sermons should provide hope and context for congregants' lives.

New preachers should embrace their journey and growth in preaching.

Effective preaching invites belief and engagement with the good news.

The process of sermon preparation is integral to a preacher's discipleship.

Preaching should not be reduced to thematic series disconnected from scripture. What's hardest for me is receiving affirmation or love.

I would be perfectly content to swoop in and disappear.

I've learned about controlled vulnerability in preaching.

It's uncomfortable to draw attention to oneself in the pulpit.

We all have personal struggles that may or may not be helpful to share.

Learning from mistakes is crucial in preaching.

Sermons that never touch life are boring.

You have to spend enough time with scripture to understand its complexities.

Sermon preparation is a primary aspect of my devotional life.

True and beautiful things should find their way into sermons.

Sound Bites

"What's your process for preaching?"

"I don't preach from the lectionary anymore."

"I think the gospel is a promise."

"You have to name the elephant in the room."

"God loves being our God."

"Convey it in a way that invites belief."

"What's hardest for you in preaching?"

"I want to zero in on that with you."

"It was uncomfortable."

"We all have things that we're going through."

"Learning from mistakes is important."

"Sermons that never touch life are boring."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 5, 2025

“Love Your Family First” Does Not Land a Cross on Your Back

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Luke 10

This is not an attempt to pile on the new vice president, chase news-related clicks, or presume a prophetic posture. It’s just a sermon from the vault, from this month at the start of Trump’s first term.

Many of have rightly critiqued JD Vance’s grasp of Christianity’s ethic of love for the neighbor; however, much of the pushback has deployed Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan in a moralistic fashion— Jesus did not need to be crucified for such interpretations.

Neither Vance nor his critics seem aware of the parable’s actual offense. “Love your family first” does not land a cross on your back. We killed Jesus for telling stories like the one about the Samaritan.

Here is the sermon…

In front of a crowd of 70 or 140— who's to say how big the crowd really was— this lawyer tries to trap Jesus by turning the scriptures against him.

“Who is my neighbor?” the lawyer presses.

It's the kind of Bible question they could have debated for weeks. Read one part of Leviticus and God's policy is Israel First.

Your neighbor is just your fellow Jew.

Read another part of Leviticus and your neighbor includes the immigrants and refugees in your land.

Turn to another Bible passage, and the aliens who count as your neighbor might really only include those who've converted to your faith. Your neighbors might really only be the people who believe like you believe.

Read the right Psalms, and neighbor definitely does not include your enemies. It's naive, sing those Psalms, to suppose your enemies are anything other than dangerous.

So they could have sat around and debated on Facebook all week, which is probably why Jesus resorts to a story instead, about a man who gets mule-jacked, making the 17-mile trek from Jerusalem down to Jericho, and who's left for dead, naked in a ditch on the side of the road.

A priest and a Levite respond to the man in need with only two verbs to their credit.

See.

Pass by.

But, like State Farm, it's a Samaritan who's there for the man in the ditch. Jesus credits him with a whopping 14 verbs to the priest's puny two verbs. The Samaritan comes near the man, sees him, is moved by him, goes to him, bandages him, pours oil and wine on him, puts the man on his animal, brings him to an inn, takes care of him, takes out his money, gives it, asks the innkeeper to take care of him, says he'll return and repay anything else.

14 verbs.

Fourteen verbs is the sum that equals the solution to Jesus' table-turning question, “Which man became a neighbor?”Not only do you know this parable by heart, you know what to expect when you hear a sermon on the Good Samaritan, don't you? You expect me to wind my way to the point that correct answers are not as important as compassionate actions. That Bible study is not the way to heaven, but Bible-doing. Show of hands, how many of you would expect a sermon on this parable to segue into some real-life example of me or someone I know taking a risk, sacrificing time, giving away money to help someone in need.

How many of you would expect that?

Right. I know how many of you all would expect me to try to connect the world of the Bible with the real world by telling you an anecdote?

An anecdote like, on Friday morning…

I drove to Starbucks to work on a sermon. As I got out of my car standing in front of Starbucks, I saw this guy standing in the cold. I could tell from the embarrassed look on his face and the hurried, nervous pace of those who skirted past him that he was begging. And seeing him standing there, pathetic, in the cold, I thought to myself, crap. How am I going to get into the coffee shop without him shaking me down for money?

I admit it's not impressive, but it's true. I didn't want to be bothered with him. I didn't want to give him any of my money. Who's to say that what he'd spend it on or if giving him a handout was really helping him out? I know Jesus said to give to people whatever they asked from you, but Jesus also said to be as wise as snakes. And I'm no fool. You can't give money to every single person who begs for it. It's not realistic. Jesus never would have made it to the cross if he stopped to help every single person in need. I thought to myself.

Mostly I was irritated. Irritated because on Friday morning I was wearing my clergy collar.

And if Jesus, in his infinite sense of humor, was going to thrust me into a real-life version of this parable, then I was darned if I was going to get cast as the priest. I sat in my car with these thoughts running through my head, and for a few minutes I just watched. I watched as a Starbucks manager saw him begging on the sidewalk and passed by. Then a PetSmart employee saw him begging and passed by. Then some moms in workout clothes pretended not to see him and passed by. When I walked up to him, he smiled and asked if I could spare any cash.

“I don't have any cash on me.” I lied.

I asked him what he needed and he said food. Motioning to the Starbucks behind us I offered to buy him breakfast but he shook his head and explained, no I need food like groceries for my family. And then we stood in the cold and Jameson, his name was Jameson, told me about his wife and three kids and the motel room on Route 1 where they'd been living for three weeks since their eviction, which came two weeks after he lost hours at his job. After he told me his story, I gave him my card and then I walked across the parking lot to shoppers and I bought him a couple of sacks of groceries, things you can keep in a motel room, and then I carried them back to him. It wasn't 14 verbs worth of compassion, but it wasn't shabby.

And James smiled and said, thank you. And then I took his picture. Tacky, I know. But I figured you'd never believe this sermon illustration just fell into my lap like manna from heaven without a picture. So I took his picture on my iPhone. And then having gone and done likewise, I said goodbye. And I held out my hand to shake his.

See?

Isn't that exactly the sort of story you'd expect me to share?

A predictable slice of life story for this worn out parable right before I end the sermon by saying go and do likewise.

And I expect you would go feeling not inspired but guilty.Guilty knowing that none of us has the time or the energy or the money to spend 14 verbs on every Jameson we meet.

If 14 verbs times every needy person we encounter is how much we must do, then eternal life isn't a gift we inherit at all.

It's instead a more expensive transaction than even the best of us can afford.

Good news? The good news and the bad. There's more to the story. I shook Jameson's hand while in my head I was cursing at Jesus for sticking me in the middle of such a predictable sermon illustration.

And then I turned to go into Starbucks when Jameson said, “You know, when I saw you as a priest, I expected you'd help me.”

And then it hit me.

“Say that again?”

“When I saw who you were,” he said, “The collar. I figured you'd help me.”

And suddenly it was as if he'd smacked me across the face.

We've all heard about the Good Samaritan so many times, the offense of the parable is hidden right there in plain sight.

It's so obvious we never notice it.

Jesus told this story to Jews.The lawyer who tries to trap Jesus, the 72 disciples who've just returned from the mission field, the crowd that's gathered around to hear about their kingdom work, no matter how big that crowd was, every last listener in Luke chapter 10 is a Jew.

And so when Jesus tells a story about a priest who comes across a man lying naked and maybe dead in a ditch, when Jesus says that the priest passed him on by, none of Jesus' listeners would have batted an eye. When Jesus says, so there's this priest who came across a naked, maybe dead, maybe not even Jewish body on the roadside, and he passed on by the other side, no one in Jesus' audience would have reacted with anything like, “that's outrageous.”

When Jesus says, “there's this priest, and he came across what looked like a naked dead body in the ditch, and he crossed by on the other side,” everyone in Jesus' audience would have been thinking, “what's your point? Of course he passed on by the other side. That's what a priest must do.”

Ditto the Levi.

No one hearing Jesus tell this story would have been offended by their passing on by. No one would have been outraged.As soon as they saw the priest enter the story, they would have expected him to keep on walking. The priest had no choice for the greater good. According to the law, to touch the man in the ditch would ritually defile the priest. And under the law, such defilement would require at least a week of purification rituals, during which time the priest would be forbidden from collecting tithes. Which means that for a week or more, the distribution of alms to the poor would stop. And if the priest richly defiled himself and did not perform the purification obligation, if he ignored the law and tried to get away with it and got caught, then according to the law, he could be taken out to the temple court and beaten.

Now, of course, that strikes us as contrary to everything we know of God.

But the point of Jesus's parable passes us by if we forget that none of Jesus' listeners would have felt that way. As soon as they see a priest and a Levite step onto the stage, they would not have expected either to do anything other than what Jesus says they did. So, if Jesus' listeners wouldn't have expected the priest or the Levite to do anything, then what the Samaritan does isn't the point of the parable.

If there's no shock or outrage at what appears to us a lack of compassion, then no matter how many hospitals we name after the story, the act of compassion isn't the lesson of the story.

No matter how many hospitals we name after the story, the act of compassion isn't the lesson of the story.

If no one would have taken offense that the priest did not help someone in need, then helping someone in need is not this teaching's takeaway.

Helping someone in need is not the takeaway.

A little context.

In Jesus' own day, a group of Samaritans had traveled to Jerusalem, which they did not recognize as the holy city of David. And at night, they broke into the temple, which they didn't believe held the presence of Yahweh. And they ransacked it, looted it. And then they littered it with the remains of human corpses, bodies they'd dug up.

So in Jesus' day—

Samaritans weren't just strangers, they weren't just opponents on the other side of the Jewish aisle, they were other.They were despised.

They were considered deplorable.

Just a chapter before this, an entire village of Samaritans had refused to offer any hospitality to Jesus and the disciples. And the disciples' hostility towards them is such that they begged Jesus to call down an all-consuming holocaust upon the village.

In Jesus' day, there was no such thing as a good Samaritan.

That's why when the parable is finished and Jesus asks his final question, the lawyer can't even stomach to say the word Samaritan. “The one who showed mercy,” is all the lawyer can spit out through clenched teeth. You see, the shock of Jesus' story isn't that the priest and the Levite fail to do anything positive for the man in the ditch.

The shock is that Jesus does anything positive with the Samaritan in the story.The offense of the story is that Jesus has anything positive to say about someone like a Samaritan. We've gotten it all backwards.

It's not that Jesus uses the Samaritan to teach us how to be neighbors to the man in need.

It's that Jesus uses the man in need to teach us that the Samaritan is our neighbor.

The good news is that this parable, it isn't the stale object lesson about serving the needy that we've made it out to be.The bad news is that this parable is much worse than most of us ever realized.Jesus isn't saying that loving our neighbor means caring for someone in need. You don't need Jesus for a lesson so inoffensively vanilla. Jesus is saying that even the most deplorable people, they care for those in need. Therefore, they are our neighbors, upon whom our salvation depends.

I spent last week in California promoting my book, which, if you'd like to pull out your smartphones now and order it on Amazon, I won't stop you. On inauguration day, I was being interviewed about my book. Or at least, I was supposed to be interviewed about my book. But once the interviewers found out I was a pastor outside DC, they just wanted to ask me about people like you all. They wanted to know what you thought, how you felt, here in DC, about Donald Trump. And because this was California, it's not an exaggeration to say that everyone seated there in the audience was somewhere to the left of Noam Chomsky. Seriously, you know you're in LA when I'm the most conservative person in the room.

So I wasn't really sure how I should respond when, after climbing on top of their progressive soapbox, the interviewers asked me, “What do you think, Jason? What do you think we should be most afraid of about Donald Trump and his supporters?”

I thought about how to answer.

I wasn't trying to be profound or offensive.

Turns out I managed to be both.

I said:

“I think with Donald Trump and his supporters, I think, Christians at least, I think we should be afraid of the temptation to self-righteousness. I think we should fear the temptation to see those who have politics other than ours as other.”

Let's just say they didn't exactly line up to buy my book after that answer. Neither was Jesus' audience very enthused about his answer to the lawyer's question.

You know, as bored as we've become with this story, the irony is we haven't even cast ourselves correctly in it.

Jesus isn't inviting us to see ourselves as the bringer of aid to the person in need.

I wish! How flattering is that?

Jesus is inviting us to see ourselves as the man in the ditch and to see a deplorable Samaritan as the potential bearer of our salvation.Jesus isn't saying that we're saved by loving our neighbors and that loving our neighbors means helping those in need.

No, Jesus is saying with this story what Paul says with his letter, that to be justified before God is to know that the line between good and evil runs not between us and them, but through every human heart, that our propensity to see others as other isn't ideological purity, it's our bondage to sin.

All people, both the religious and the secular, Paul says, all people, both the right and the left, Paul could have said, both Republicans and Democrats, both progressives and conservatives, both black and white and blue, gay or straight, all people, Paul says, are under the power of sin. There is no distinction among people, Paul says, because all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. No one is righteous, not one, Paul says. Therefore, you have no excuse. In judging others, you condemn yourself, Paul says. You're storing up wrath for yourself, Paul says. No one is righteous, not one. So if you want to be justified instead of judged, if you want to inherit eternal life instead of its eternal opposite, then you better imagine yourself as the desperate one in the ditch and imagine your salvation coming from the most deplorable person your prejudice and your politics can conjure up.

Don't forget, we killed Jesus for telling stories like this one.And maybe now you can feel why.

Especially now.

Into our partisan tribalism and our talking past points, into our red and blue hues, our social media shaming, into our presumption and our pretense at being prophetic, into all of our self-righteousness and defensiveness, Jesus tells a story where a feminist or an immigrant or a Muslim is forced to imagine their salvation coming to them in someone wearing a cap that reads, Make America Great Again.

Jesus tells a story where a tea party person is near dead in the ditch and his rescue comes from a Black Lives Matter lesbian.

Where the Confederate-clad redneck comes to the rescue of the waxed-mustached hipster. Where the believer is rescued by the unrepentant atheist. A story where we're the helpless, desperate one in the ditch, and our salvation comes to us from the very last type of person we would ever choose.

And when Jesus says, and do likewise, he's not telling us we have to spend 14 verbs on every needy person we encounter. I wish. He's telling us to go and do something much costlier. And countercultural. He's telling us that even the deplorables in our worldview, even those whose hashtags are the opposite of ours, even they help people in need. Therefore, they are our neighbors. Not only our neighbors, they are our threshold to heaven, Jesus.

It's no wonder why we're still so polarized.

After all, we only ever responded to Jesus' parables in one of two ways, wanting nothing to do with him or wanting to do away with him.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 4, 2025

If Jesus is Risen, Where is His Body?

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

1 Corinthians 15.1-11

One of the gospel-minimum components of the church’s resurrection proclamation poses a particular problem for believers who live after Copernicus. Modern people remain every bit as superstitious as our ancient forebears, yet the claim of Jesus’s bodily resurrection presents a difficulty for us that it did not for them. Specifically, to be a body is to be locatable. A minimum consideration to register about the body of Jason Micheli, for example, is that you can now find it, sitting comfortably with a cup of coffee, outside of Washington DC.

So then, where is the body of Jesus?

Prior to Copernicus, the church’s canon and creed provided a simple solution to this question. The Father raised the Son to sit at his right hand in heaven.

As though he drank too much Fizzy Lifting Drink, the ancient church presumed the Risen Jesus gets to heaven by moving through space to the boundary of the earthly space and the heavenly one.

February 3, 2025

"There is a space, there is an interval between Christ’s rising and ours because God will not abandon what he has made."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

The lectionary epistle for this coming Sunday is from Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, 15.1-11:

“Now I want you to understand, brothers and sisters, the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which also you stand, through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you--unless you have come to believe in vain. For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures and that he was buried and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. For I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God. But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace toward me has not been in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them,though it was not I but the grace of God that is with me. Whether then it was I or they, so we proclaim and so you believed.”

Critically, Paul’s argument does not end with verse eleven.

“But now,” Paul writes, and with that temporal adverb hitched to that tiny conjunction he swings up from the gloom and the dark and the doubt and the pitiable possibility into a blinding light.

“But now Christ has been raised from the dead!”And we can do the same!

February 2, 2025

“Amen” is Faith’s Biggest Word

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, why not?!

I was a rookie pastor the first time it struck me what is at stake in a prayer request. You know how the phone tree works. Someone in my little congregation in New Jersey knew someone whose neighbor’s child had just been in a car accident. The family did not have a church home. So Irma— my organist, lay leader, and custodian— rang my flip phone.

“You hustle on over there,” Irma ordered me. “They need prayer. And later, they’re going to need a preacher.”

Despite what you may think, I tend to do what I’m asked to do and so about fifteen minutes after getting the call I hustled off campus and drove the short distance to Princeton Hospital. Darrien was a senior in high school. When I got there I saw that his dark skin was broken across his temple. They were a poor family with little money and no airbag. The ER stall was filled with family members and hospital staff whose laggard motions told me it was just a matter of time.

I had worn my newly-purchased collar to minimize introductions and explanations.

When Darrien’s mother saw me, she brooked no time for pleasantries. She pointed a long manicured finger at me. She did not ask. She demanded.

“You pray for him right now. You get God to mend him. You tell God to let me keep my baby.”

I prayed just as bluntly as she had registered her request. Afterwards, I held Darrien’s mother’s hand when I wasn’t letting her cling to me like a rescue buoy. I kept vigil with them. When they moved Darrien to a room in the critical care unit, I left them with a promise to return the next day. His vitals had proved more resilient than initially expected, a turn of events his mother and family attributed to my talismanic power of prayer.

Just so, they were anxious for me to return.

The next morning I knocked on the glass, pulled the sliding door open, and stepped through the curtain. The monitors were quiet and blank. And Darrien’s body was still, waiting now for the resurrection. When I approached the bed, his mother smacked me so hard she knocked crumbs of toast out of my mouth.

Then she broke the silence with an agonized peal, “Your prayer didn’t work! You didn’t do it right! What kind of preacher are you?! God didn’t answer!”

I wrapped my arms around her.

She muttered it into my shoulder over and again, “It didn’t work. It didn’t work. You didn’t do it right.”

Here is my question.

Did it?

Did my prayer not work?

Did God elect not to answer my petition?

This past week I received a prayer request of sorts from a woman who was a youth in my first confirmation class over twenty years ago.

She wrote to me:

“Pray for my dad and for me. Pray for our relationship. I have been praying for months— years even— that Donald Trump would not return to the White House. And I have been praying not because I am especially interested or invested in politics; I have been praying because politics has kidnapped my father. When he is not watching cable news shows or listening to podcasts, he is on the internet. It has become his church. His cruel jokes and dismissive barbs— it is not him. At first, we just could not discuss current events or political issues with one another. But now, we cannot speak to one another at all. There is not hostility between us exactly. It is more like there is this absence between us. I could have put holes in the rug I have prayed so hard and so often that the course of things not lead here. So I guess I am asking you to pray, Jason, because obviously— though you are the one who taught me— I do not know how to do it. I cannot think of a single one of my prayers that have been answered. I have stopped trying. And I do not know if I would consider myself a believer anymore.”

Here is another question.

Is it possible for prayer to fail?

A couple of year ago, I was driving to the office when the theologian Stanley Hauerwas called me. He had been ill and had undergone surgery in England, and I had left him a message inquiring about his health and spirit.

That morning on the way to church, he called me back and before I could even say hello, his gravely Texas accent barked out, “Jason I can’t piss, and it’s just so damn painful.”

As I pulled into the church parking lot, he described all the complications he’d suffered following what should have been a routine procedure. I listened. But I knew that Stanley is not the sort of Christian to be satisfied with a preacher who offers nothing but active listening.

So I said to him, “I will pray for you, Stanley.”

“You damn well better do it now,” he grumbled, “I’m miserable, in agony.”

I cleared my throat and was about to begin praying when Stanley interrupted me.

“And Jason?”

“Yes, Stanley?”

“If you’re not going to pray for God to heal me, then, hell, just hang up the phone right now already.”

I did pray for God to heal him.

And Stanley did heal.

Does that mean my prayer worked?

For that matter, if God is beyond all grasping, is it even right to speak of prayer as working?

Here is yet another question.

What is the difference between prayer and magic?

What is the difference between me and Dumbledore?

In the Book of Samuel, after David is anointed king first over the house of Judah and later over Israel in the north, the LORD makes a covenant with the shepherd boy from Bethlehem. “He shall build a house for my name,” God pledges, “And I will establish his throne forever…my steadfast love will never depart from him.”

And in response to God’s unconditional promise, David prays. David goes into the tabernacle to sit before the LORD. And David speaks to God.

He utters praise:

“Who am I, O LORD God, and what is my house, that you have brought me to this place in life? And yet this was a small thing in your eyes, O LORD God…Because of your promise, and according to your own heart, you have brought about all this greatness, to make your servant know it.”

You have brought me to this place in life.

In other words, David’s praise acknowledges that it could have been otherwise. The LORD could have led David in another direction. God could have elected to bring his life to a different place.

“My life could have been otherwise,” David professes to the Will behind all the happenings that happen.

David repeats this same acknowledgement in the twenty-third psalm, “He leads me in faithful tracks for his name’s sake.”

On Thursday I met with a team of oncologists at Johns Hopkins for a second opinion on my cancer recurrence and course of treatment. With a soft Dutch-Afrikaans accent, the lead doctor introduced himself to me by saying, “First things first, Mr. Micheli. Medicine makes amazing advances all the time, but— remember— there is no cure for mortality.”

I nodded.

“I get it,” I said, “That’s sort of my line of work too.”

He did not inquire about the particulars of my vocation but instead he sat down and hurried to the matter at hand, reviewing two alternative regimens in exhaustive, jargon-laden detail. After thirty minutes, he recommended I remain on my present course of treatment. He then brushed his palms on his thighs, stood up from his round stool, and held out his hand to me.

“It was very nice to meet you,” he said.

“Those two,” I said, still trying to process his debrief, “Those are the only other alternatives?”

He stopped. He turned away from the door. And he faced me.

After a beat or two, he broke the pregnant silence, “You could pray.”

“Pray?” the surprise in my voice surprised me, “I guess that is significantly more affordable than the other alternatives.”

“Yes,” he said flatly, not catching the joke.

“Pray?” I repeated.

“Yes,” he said, “You could pray. Tell me, are you not religious?”

“Uh, sort of,” I replied, “I just did not expect to receive a second opinion on prayer.”

A heavy seriousness immediately settled over his face like the sun disappearing behind a cloud. He put a warm hand on my elbow. He leaned towards me. And looking me straight in the eyes, his soft voice became but a whisper.

“If prayer is not possible…,” he said, and with his hands he gestured towards all the monitors and computers and examination equipment in the room.

“If prayer is not possible, what is the point? If there is not One to whom we can pray, if there is not One who holds the future in his hands, then there is no future. There may be tomorrow and the next day and so forth, but there is no Future. And if there is no future, what is the point? Everything is meaningless— your life is meaningless.”

“I bet you have got quite the bedside manner.”

He smiled.

“So that is your prescription?” I asked.

“No,” he answered, “It is not a prescription. It is not a prescription because there is no guaranteed outcome. And the reason there can be no guaranteed outcome is not because there is no God. The reason there can be no guarantee is because God is real. And because he is real, he is free. Good day to you, sir.”

“He leads me in faithful tracks for his name’s sake.”

By “faithful tracks” David does not mean the LORD has set him on a path to faithfulness. Nor does David praise God for steering him towards righteous deeds or works of justice. Rather David is extolling the LORD’s own faithfulness.

As the Old Testament scholar John Goldingay comments on verse three:

“The psalm is not introducing a moral note and asking to be led to live the right kind of life. Faithful tracks are paths consistent with the divine shepherd's faithfulness. David's confession corresponds to the declaration in the Song of Moses that Yahweh is leading Israel with commitment. Thus does “for his "name's sake" restate the previous clause. Yahweh is a God characterized by faithfulness. In a sense, that is the meaning of the name "Yahweh." So acting in faithfulness demonstrates that the name is a true reflection of the character.”

“Faithful tracks” are paths consistent with God’s faithfulness.

Hence, wherever the LORD leads you in life, he does so in a manner consistent with his steadfast love. Which is to say, whatever life brings you, nevertheless God is shepherding you pursuant to his faithfulness. Your path is always congruent with his commitment to you. No matter what befalls you, it is leading somewhere. And he is never not ahead of you. That is, no matter what transpires in your present, regardless of what betided in your past, your future will vindicate the Father whose name is faithfulness.

No matter the place life has brought you, it is leading somewhere good.

Maggie Ross is a Anglican solitary in Oxford, England. From her vowed life of silence a number of books on the Christian spiritual life have emerged. In her book Writing the Icon of the Heart, Ross unravels the distinction between praying to God in order for our prayers to work and praying to the Father as the Bride of his Beloved Son. The former attempts to force a divine intervention. The latter yields to a trusted lover. The former hardens our hearts and deadens our faith. The latter makes us as human as God.

As Maggie Ross writes:

“If theology has forgotten it, Einstein reminds us that there are many futures. Prayer, especially intercessory prayer, is opening to this possibility of many futures. Magic wishes to limit us to only one future. Magic tries to exert total short-term control over a single, narrowly focused aspect of life, heedless of the long-term consequences or ripple effect on others’ lives.

In our desperation to pray for a loved one in crisis, we often feel strongly about what the best outcome should be, and we frame our prayers (and sometimes fill them with bribes) toward this end. In reality it is impossible for us to know what will work for the highest good, and unless our prayer is underpinned and ringed about with “Thy will be done” it is no better than magic. By contrast, true prayer tries to gather what needs attention and let go of it in the love of God.

Weeping is often a sign of relinquishing of our efforts to control the future. Weeping is a sign of our letting go of power so that God’s power can move through us. It is the sign of transfiguration, of new creation. The difference between prayer and magic is an attitude toward the future.”

In other words, to pray is simply to entrust your future to the LORD.

Or as Robert Jenson says, “Amen— let it be so— is faith’s biggest word.”

Look—

Not to make it about me, but: Exhibit A.

I was first diagnosed with this rare, allegedly incurable cancer ten years ago. Since then, I have known that the median time to relapse for my disease is seven years. Do the math, for the last three years every day has felt like Ash Wednesday. For the past three years, I have waited, knowing each passing day was another grain of sand slipping through the hourglass.

From dust I came and to dust I shall return.

I did not want what science calls my fate to be my future.

And so I have prayed.

And prayed.

And prayed.

I pleaded and petitioned.

I did not want to be here.

Nevertheless, this is the place where he has shepherded me.

And truly, it’s grassy pastures and still waters.

I am at peace because I trust that even this path will prove to be a faithful track by which God will justify his name. Even at this tipping point between my living and my dying, I can speak faith’s biggest word.

Amen.

Let it be so.

I say all this not to present myself in a sanctified light. I say all this to point you to what I know in my bones— literally, in my bones— to be true. There is no prayer that falls on deaf ears. There is no petition that fails receipt. Every uttered word works. No plea or praise spoken to the LORD are sunk costs. On account of the Son, the Father has promised to hear you. To hear you out as one of his children. And he will do so by grace not according to your merit or demerit. Therefore, all your prayers are heard and heeded.

Church:

The LORD heard your prayers for Mike Moser.

The LORD heard your prayers for Gary Sherfey.

The LORD heard your prayers for Steve Reynolds.

The LORD hears your prayers…

For me, for Laura Kallal and her family, for your marriage, for your divorce, for your kids, for your jobs, for your health, for the nation.

It is not that God ignores your intercessions. It is that you can trust him with your future. He can be entrusted with your future, even if, especially if, it is not the future you requested. And you can entrust your future to the LORD because— back to David— any place the LORD leads you in life and every path he sets before you, they are all “faithful tracks.” That is, they are all points from which the LORD can lead you to a future that will not only vindicate his name, Faithfulness, but also will vindicate his Son who was crucified for your sins and raised for your justification.

Admittedly, getting to Amen on such an affirmation is faith’s biggest leap.

But then again, the scriptures make clear that faith is not an accomplishment.

Or rather, faith is God’s accomplishment in you.

My cheek was still bruised from the blow Darrien’s mother had struck when she wandered into church for the first time. Not knowing better, she arrived early that Sunday, bringing her elderly father and her adolescent daughter with her. I was in the narthex, tying the cincture on my robe. Irma was wheezing out some asthmatic chords on the ancient, dusty organ. Darrien’s mother was the opposite of how I’d seen her in the hospital, all decked out in Sunday-best.

She pointed at my face, “I’m sorry about that.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

An uncomfortable silence fell over us.

“I didn’t expect to see you here,” I said, “I guess I should’ve invited you. I’m new at this. I haven’t even been a Christian all that long.”

“Your prayer may not have worked,” she explained, “but I can’t stand the thought that that day wasn’t leading somewhere. That that was…it.”

I nodded, too young and far out of my depth.

“I’m terrified,” she said, “by the notion that God isn’t. I need to know he is— that’s why we’re here.”

“Well, that’s easy,” I replied.

And she looked at me funny.

So I took a step back and gestured to the gap between us.

“God exists,” I said, “Jesus is the Word. That means God occupies every space in between someone who makes a promise in his name and someone who receives his word of promise. So God is right here when I promise you that because Jesus lives, your future is with Darrien. That day is leading somewhere.”

She chewed on it, didn’t reply, and then led her family to find a place in the pews. It took a couple of months of Sundays, I noticed, before she could add her voice to the Body and respond to the promise of the gospel with faith’s biggest word, “Amen!”

To pray is to entrust your future, the future, the future of someone you love to the LORD. But here’s the rub. You can only trust someone you have come to know. Just so, for you to trust God you must encounter him. Which is a miracle, but it’s incredibly easy and ordinary. I may have been a rookie pastor, but I was not wrong. It’s the Reformation. God exists— no. The LORD occupies this space. God occupies this space between me and you, in the transmittance of a promise, handed over on the basis of the gospel.

For example—

Wherever you are in life, whatever path you’ve gotten lost on, no matter what has befallen you, the LORD Jesus Christ will turn it into a faithful track. The story of the life you call you, the sum of it, will give glory to his name.

There—

You wonder where God is?

God just did God to you.

You can only entrust your future to someone you know, someone who has made a promise to you and given of himself to you.

Therefore, come to the table.

And don’t let the loaf and the cup fool you.

God is here, in the promise, “This is my blood…for you.”

Come to the table.

And I dare you—

Taking the bread, receiving the cup…say “Amen.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 1, 2025

Preachers: Do You Like Your People?

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!?

“Expectations,” Paul Zahl writes in Grace and Practice, “are the enemy of love.” When others do not measure up to the expectations we have (sometimes subconsciously) set for them, our hearts harden and our love curdles into its opposite. Luther expressed this same insight in relationship to the commandments, lex semper accusat.

The law always accuses.

While I’ve often quoted Zahl in wedding homilies, of late I have pondered the danger of expectations with respect to public proclaimers of the gospel. What happens, I wonder, when preachers step into the pulpit with expectations for who their hearers are, for what they are capable of doing, and— especially these days— for which politics espouse.

Simply—

I wonder if preachers’ (political) expectations frustrate their ability to love their listeners.

While white evangelicals bear nearly the entirety of the media’s scorn for their unflagging support of the once and again president, it is nonetheless true that 61% of a mainline tradition like my own United Methodist Church likewise voted for him. In fact, the percentages are so consistent across denominations, professor of political science Ryan Burge contends that, statistically speaking, there is no viable demographic for progressive Christianity in the United States.

A cursory glance at social media, however, illustrates how thoroughly Mainline clergy belong to the college-educated elite that now comprise the Democratic Party’s primary constituency. In other words, mainline preachers proclaim Luke 4 from within the party of wealth and advanced degrees.

This disparity often leads clergy to communicate in public in a manner that suggests no one in their audience or congregation disagrees with them when, in fact, the numbers make it a certainty that over half do.

It is frustrating enough that our hearers come to church with bound wills and simply cannot be relied upon to change much less build the kingdom. It must be even more frustrating that over half do not find preachers’ political entreaties persuasive.

Again, I wonder: are preachers’ expectations for their people the enemy of love?Because a hot minute spent on Twitter or Facebook suggests that are a good many preachers who do not even like their people. And liking them is the threshold for gospel proclamation.(To be clear: chief among sinners, here).

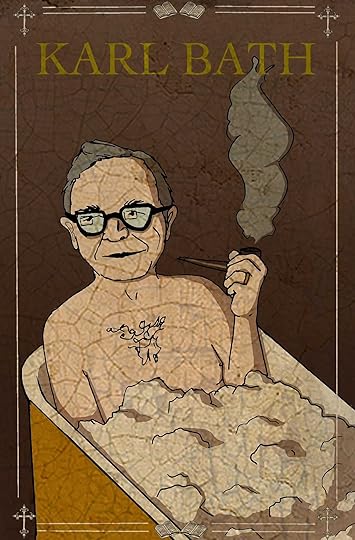

This is the counsel given by Karl Barth during the theologian’s only visit to America at the end of his career. As noted by his longtime assistant, Eberhard Busch, during his Warfield Lectures at Princeton a student asked Barth:

“What one thing, sir, would you tell a young pastor today, if you were asked, is necessary in this day and age to pastor a Church?”

And Barth replied in his typically exhaustive fashion:

“Ah, so big a question! That is the whole question of theology, you see! I should say, I hope that during your studies you have visited yourself earnestly with the message of the Old Testament and of the New Testament. And not only of this message but also of the Object and the Subject of this message. And I would ask you, are you trained to visit not only yourself now, but a congregation with what you have learned out of the Bible and of church history and dogmatics and so on? Having to say something, having to say that thing.

And then the other question:

Are you willing now to deal with humanity as it is? Humanity in this twentieth century with all its passions, sufferings, errors, and so on?Do you like them, these people?Not only the good Christians, but do you like people as they are?People in their weaknesses?Do you like them, do you love them?And are you willing to tell them the message that God is not against them, but for them?

That’s the one real thing in pastoral service and that is the question for you. If you go into ministry to do that work, pray earnestly.

You’ll do difficult work but beautiful work.But if I had to begin again anew for myself as a young pastor, I would tell myself every morning, well, here I am: a very poor creature, but by God’s grace I have heard something. I will need forgiveness of my sins everyday. And I will pray, God, that you will give me the light, this light shining in the Bible and this light shining into the world in which humanity is living today. And then do my duty.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 30, 2025

The Mystery of Christ

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Hi Folks,

Here is the most recent discussion of Capon’s The Mystery of Christ. You can join us live on Monday night at 7:00 EST, HERE.

Show Notes

Also, based on some questions I’ve received, it occurred to me that I owed you all an update on my health and treatment. Shortly after Christmas I started treatment for my Mantle Cell Lymphoma— I’ve been self-administering chemotherapy twice a day. Minus the side effects, to which I’m adjusting, I feel better than I have since May. It’s possible I’ll continue with this indefinitely. However, I am meeting with doctors at Johns Hopkins this week to explore alternative, more aggressive options which would both free me from having to do this current treatment indefinitely and would push the likelihood of recurrence further into the future. All you need to know, really, is that I feel better than I have in a long time.

God is good and I covet your prayers.

Summary

The conversation explores themes of justice, mercy, and forgiveness within the context of a recent sermon. The participants reflect on the implications of the sermon, the role of the pulpit, and the nature of relationships in light of the gospel. They discuss the challenges of Christian identity and the importance of being neighbors to one another, emphasizing the need for grace and understanding in a polarized society. The dialogue culminates in a call to recognize the mystery of Christ and the transformative power of forgiveness.

Takeaways

The importance of addressing the context of a sermon.

Justice and mercy are intertwined in Christian teaching.

Forgiveness is essential for restoring relationships.

The church's role is to proclaim the gospel, not manage it.

Christian identity is often sorted into political categories.

The nature of relationships reflects the heart of the Father.

Romance and justice can be seen as contrasting themes.

The mystery of Christ encompasses all of creation.

Being a neighbor means advocating for those in need.

Forgiveness is a consequence of recognizing grace.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 29, 2025

Outrage Porn, Glawspel, and God's One-Way Love

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, why not?!

Journalist Chris Cilliza recently made a wise observation about the incentives to express outrage over the once and again president.

He writes:

“In the decade since Trump came down the golden escalator, a cottage industry has developed: Outrage porn.

What is outrage porn and who does it? It’s anything that is designed to make you angry. To piss you off. The purveyors? Mostly writers and pundit types who have made a very good living by being shocked, appalled, angry and, yes, outraged by every little thing Trump has done. Candidly, it’s exhausting. And, from a political standpoint, it’s proven to be almost entirely ineffective.”

A week into the next four years, and I’m definitely exhausted— and I’ve largely tuned out the news as best as I can.

I mention this not to dabble in politics but because the cottage industry Cilliza identifies has a theological correlative, glawspel:

Muddling the gospel with the law.

The outrage compels many Christians, preachers especially, to hortatory, muddling the gospel with the law, and positing, for example, “social holiness” as itself the good news rather than its fruit. The gospel of baptism, for instance, is not that the candidate pledged to “resist the spiritual forces of wickedness;” the gospel of baptism is that the word attaches to water so as to cloth the candidate in Christ’s own righteousness, Jesus’ permanent, perfect record. While outrage may be understandable, perhaps even justified, there is a cost that comes with letting politics lure us away from the promise of what Paul Zahl calls God’s one-way love in Jesus Christ.

Going all the way back to Augustine and later to Luther, the church’s insistence on the primacy of grace as both the content and mode of our message has always been a matter of pastoral concern.

Robert Jenson explains what’s at stake:

“Augustine’s fundamental insight, against Pelagians or Arminians (full, semi-, demi-semi-, or whatever) is veridical: theology that makes my conversion, or my subsequent persevering in sanctity or growing in it, dependent on my own decision to seek holiness or on my own sanctified decisions or actions, must “beware, lest … the grace of God be thought to be given somehow in accord with our merit, so that grace is no longer understood as grace” [De praed. sanct. 1.6]. There is indeed no escaping the logic: if at any step or stage of spiritual life my choice or action determines whether or not I am in fact to be sanctified, then indeed that is what it does, and God’s role can only be to confirm my choice.

Which is to say, God’s grace is not free, and so is neither God nor grace.Augustine did not cultivate this logic for its own sake, but as a pastor, for the comfort of the bewildered North African believers of his time. They compared themselves to martyrs and other spiritual heroes of the just previous age of persecution, and had to doubt the worth of their own choices and actions; that is, if Pelagius was right, they had to doubt the possibility of their salvation.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers