Jason Micheli's Blog, page 15

March 22, 2025

“Perhaps the attempt to deal with Muslim criticism may help cure Christians of our absentmindedness.”

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Yesterday I visited St. George’s in Istanbul, the patriarchal seat of the Greek Orthodox Church. As the place where the Primate of the Greek Orthodox serves, for lay shorthand, St. George’s is analogous to Catholicism’s Vatican See. Following the Ottoman conquest in 1453, Islamic invaders deposed the Patriarchate from its original location at the Hagia Sophia. The church through which the Holy Spirit bequeathed Christianity its creedal dogma is now all but unnoticeable behind the row of cafes and restaurants that surround it. Its humble dimensions and (relatively) spare sanctuary belie its present-day prominence for Orthodox believers. Simply, you would never guess this ordinary church is the beating heart of a global body of believers. It is instead the sort of building where you would expect a church secretary to change the removable letters on the front sign every week, its front lawn sporting a banner that advertises a Friday Fish Fry.

The disparity between the splendor of the Hagia Sophia and the sheer ordinariness of St. George’s once again elicited the tension I noted earlier upon exploring the Hagia Sophia; namely, how do Christians engage their Muslim neighbors on theological grounds rather than in submission to the shallow secularism demanded by Western culture.

“We’re all on different paths to the same destination” is an empty cliche that should offend Christians every bit as much as it certainly does Muslims.

The gospel poses two stumbling blocks to Islam. These are the very same obstacles that render the gospel foolishness under the rubric of the religion of Plato:

Christology

Trinitarianism.

Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is of one being with the Father. The eternal God has not only a mother and a beginning in time but he has also an executioner and an identifiable afternoon when he died. In proclaiming the gospel in Islam’s world, Christians may address the Christological problem by lifting up Jesus of Nazareth as a prophet of God, martyred by sinful humanity, whose faithfulness the LORD vindicated by raising him from death. In the context of locution with Islam, this quite simply suffices as the whole gospel.

Nevertheless, the second stumbling block remains.

How do we speak Christian if the God in whose name we gospel is triune?This preaching task is more problematic.This pilgrimage site offers up a great irony. Constantinople is to trinitarian theology what Philadelphia is to constitutional democracy, yet today Istanbul is approximately ninety-nine percent Muslim. Where Christians should understand Trinitarianism as the highpoint of their faith’s intellectual and spiritual flourishing, Islam has always seen it as Exhibit A of Christianity’s great fall from faith in the jealous God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. In positing God as a triune identity, Islam judges Christianity as committing the primal sin of associating the God-who-is-God with an other than God. Therefore, the attempt to interpret God's triune reality in Islamic context is, as Robert Jenson writes, “the standing or falling point of any attempt to think through the faith’s mission in and for Islam.” The effort to speak Christian in a manner faithful to the Triune Name must function in at least three ways.

The first mode of gospel speech must be apologetic.

The beauty and legacy of the Hagia Sophia stands as stubborn, indefatigable reminder that trinitarian doctrine does not denote beliefs the church can jettison for the sake of dialogue.

Just as strenuously as Mohammad insisted that God is one and only one, the Body of Jesus attests that the God who is one is simultaneously three.

Trinitarian theology is the fruit of the church’s attempt to proclaim her scriptures— as the missionary gospel ventured into parts of the world shaped by the religion of Plato. Constantinople, what was once the center of Byzantine Christianity, is ground zero for this encounter. In other words, the church’s received dogma has a particular historical and cultural context; just so, believers cannot simply rip inherited slogans (“preexistence, three persons”) from this context, recite them in a very different Islamic context, and expect a fruitful outcome.

The second mode of gospel grammar is the reformation of Christian doctrine.

What most Christians actually have in their heads as "the doctrine of the Trinity" is not actually the church’s historic teaching.

In fact, what most Christians have in mind when thinking the Trinity is one of the heresies the doctrine of the Trinity was meant to overcome.Thus, as the Trinity is popularly construed by well-meaning Christians, Muslims are fully justified to object to the dogma. Here in Constantinople at two different gatherings of the church catholic, the doctrine of the Trinity was a Spirt-led effort to remedy exactly Christian relapses into pagan prejudices about deity.

For example, the church father Athanasius levied as a chief accusation against the Arians, ”. . . like the Greeks you lump creature and Creator together.” And yet, a great many Christians today— especially preachers— suppose that Trinitarianism is a matter of assimilating Jesus as closely as possible to God. This is to shirk from the Christological claims of the scriptures.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“Perhaps the attempt to deal with Muslim criticism may help cure us of this absentmindedness.”

March 20, 2025

Jesus the Risen Prophet

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Yesterday morning I landed in Istanbul, Turkey to embark on a pilgrimage with friends. Over the next ten days we will explore both the missionary journeys of Paul, the birthplace of the faith’s creedal dogma, and locus of Christianity’s patristic theology. In the same way I might visit Italy to explore the places whence my forebears came to America, I am here because— as much as the Holy Land— Constantinople is where the Christian family traces its roots.

FYI (which I’d never considered before but is obvious to anyone with a grasp of elementary Greek): It’s not the case that one name for the city is Christian and the other its Islamic alternative.

In Greek, εἰς τὴν Πόλιν is pronounced "Ees-teen-po-li" which eventually became Istanbul in modern English. It means "In the city,”and because Constantinople was the most popular and urban city at the time, when asked about Constantinople most would reply with "In the city.”

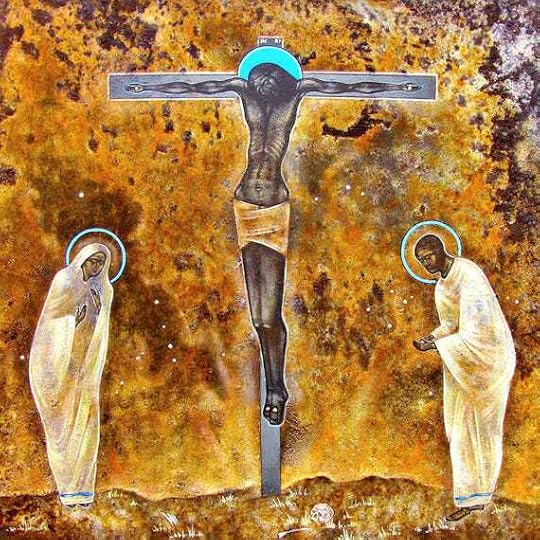

Today we visited the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Built originally in the early sixth century under the direction of the Emperor Justinian and dedicated to the triune identity Wisdom (Hagia means saint, set-apart, holy), it essentially served as the Orthodox Christian equivalent of the Vatican until the city was (finally) conquered by the Ottoman invaders in 1453. After Sultan Mehmed II’s invasion, the Ottomans converted the Christian cathedral to an Islamic mosque. From 1935 until 2019, it functioned as neither church nor mosque but as a museum, a compromise that left both parties unfulfilled and offended.

Turkey’s present-day authoritarian returned the Hagia Sophia to status as a mosque in order to appeal to his voting bloc; as a result, only a few Byzantine Christian images remain in the vast sacred space.

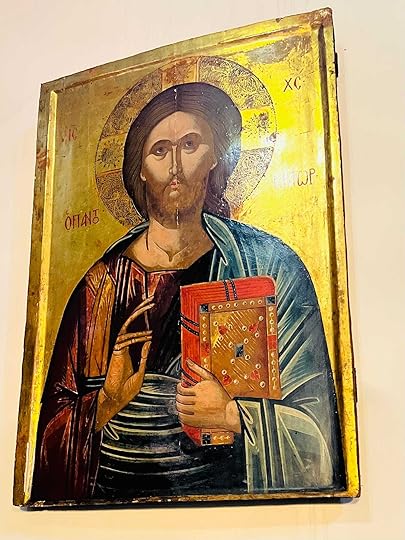

Arching my neck at odd angles and craning my arm out like a selfie-stick, my camera on the edge of my fingertips, I was able to capture a few photographs of ancient icons of Mary, Mother of God and her Son the cosmic judge. The former is screened modestly behind drapes so as to go unseen by worshippers on the floor beneath her. I did so as the chanted Arabic of Muslims’ praying their daily liturgy down below ascended to the domed, pentagonal rooftop of what was once a Christian sanctuary.

It is difficult if not impossible to be a workaday preacher at such a juncture and not ponder the alleged incongruity of faith claims. C̶o̶n̶s̶t̶a̶n̶t̶i̶n̶o̶p̶l̶e̶ Istanbul is ground zero for the nadir of one religious empire and the rise of a successor. The cross remains foolishness to the irreligious and a stumbling block to J̶e̶w̶s̶ Muslims.

Just so, it’s worth reexamining the truthfulness of the assumption that Christianity’s gospel (Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim lives with death behind him) is incompatible with the revelation received by the Prophet.

To make it plain:

Leaving aside interpretations of the commandment about graven images, so long as the Hagia Sophia remains a mosque, must those who worship there obscure icons of Jesus and his Mother and the forerunner, John the Baptist?

The drapes which hide Mother Mary at the Hagia Sophia and the giant medallions adorned in calligraphic images of the name of Allah (which themselves hide Christian icons) underscore how the stumbling blocks between Islam and Christianity have always been two chief assertions the gospel makes about God:

Mary’s boy sharing one being with the Father.

The LORD who is one constituting his oneness being in triune identities.

Christology and Trinitarianism.

But again— today I wondered anew: is it true these two deposits of faith can find no purchase among those who confess that “there is no God but Allah and Mohammad is his Messenger?”

The very fact Paul’s missionary compulsion brought him to a place that would become Byzantium suggests the answer to my question is no. That is, as soon as the Spirit coaxed the apostolic witness from its kosher kitchens in Israel, the gospel compelled preachers to utter the promise in a foreign milieu, over and against contrary claims. As a living Word, the gospel can never be preached the same way twice; therefore, the gospel would not be gospel if it could not be posited in terms Islam could even now nevertheless accommodate.

For example, the faith's necessary affirmations about Christ Jesus can in the Islamic context be made by calling him the "Risen Prophet."

That is, Christians can get to everything Christians want to say about Jesus by introducing him first as the Risen Prophet and inviting others to so address him.

March 19, 2025

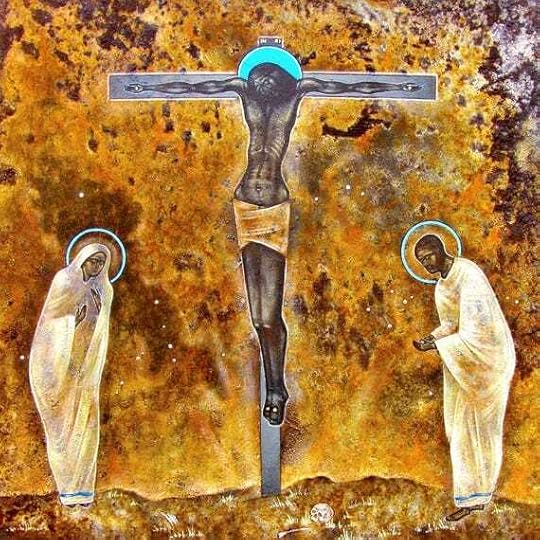

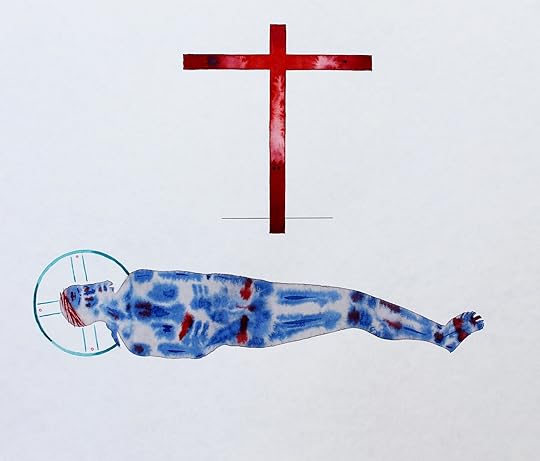

Christ's Blood: It's about Life Not Death

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

My friend Todd Littleton and I landed in Istanbul yesterday for a pilgrimage through Turkey tracing both Paul’s missionary travels and the monastic hives of the most significant church fathers. When my cancer relapsed in December and after its side effects sent me to the hospital two weeks ago, I assumed I would have to cancel on my friend. I don’t use the language of blessing casually, but I feel so to have been able to come.

“They have hospitals in Turkey too,” my oncologist sardonically replied to my query.

In getting ready to travel, we were not able to record our second session of our study of Fleming Rutledge’s book. Given my love and admiration for her, I regret this but hope to be able to join this coming Monday from Ephesus.

My conversation partner Tony send the thoughts he had prepared for that session:

The second session of our Lenten webinar based on Fleming Rutledge’s book, The Crucifixion, didn’t happen last evening. A glitch. It happens. Apologies.

The chapter on the agenda, and which will be again next Monday, March 24, was entitled “The Blood Sacrifice.” It is a terrific chapter, which covers a lot of important ground. What I want to do in this post is mostly to excerpt some key quotes from the chapter.

Let’s start at the end, the chapter’s powerful closing words, which Fleming draws her colleague at Princeton, George Hunsinger.

“Christ’s blood is a metaphor that stands primarily for the suffering love of God. It suggest that there is no sorrow God has not known, no grief he has not borne, no price he was unwilling to pay, in order to reconcile the world to himself in Christ . . . it is a love that has endured the bitterest realities of suffering and death in order that its purposes might prevail . . . the motif of Christ’s blood signifies primarily the depth of the divine commitment to rescue, protect, and sustain those who would otherwise be lost.”

Having begun with the chapter’s last word, let’s go back to its opening lines in which Fleming notes the negative reaction in mainline/ liberal congregations to “blood” imagery. (Not the case in African-American congregations.)

“In the modern period,” writes Fleming, “there has been a negative reaction in the mainline churches to the concept of the cross of Christ as a sacrifice. Disdain for the “blood” imagery of the New Testament has become widespread . . . This chapter will argue for its enduring importance.”

“One reason for the reaction against the sacrificial motif is surely the literal-mindedness of a culture unaccustomed to reading poetry. It is one of the peculiarities of our time that we support a vast entertainment industry specializing in ever more explicitly gory movies and video games while at the same time covering ourselves with a ‘politically correct’ cloak of fastidious high-mindedness.”

“When an African-American congregation sings the gospel chorus, ‘There to my heart was the blood applied/ Glory to his Name!’ they are not thinking literally, and it seems almost perverse to imply that they are. They are thinking of the power of the crucified Jesus in their own lives. We are once again in the realm of poetry.”

Part of the reason for the “negative reaction in mainline churches” is however well-founded. As I noted last week, the cross of Christ has often been presented, especially by conservative/ fundamentalists, as propitiation of an angry deity. In this it is very similar to the human, even child, sacrifice practiced in many pre-modern cultures. Such sacrificial propitiation was seen as a way of placating an angry and capricious deity. This is not what is going on in the crucifixion. “This misconception can, one hopes, be firmly laid to rest . . . the sense of placating, appeasing, deflating the anger of, or satisfying the wrath of [God] is inadmissible.”

Fleming continues, “The more important, and truly radical, reason for firmly rejecting this understanding of propitiation is that it envisions God as the object, whereas in Scriptures, God is the acting subject.” In other words, this is not a sacrifice to an angry God on high (an object) but God acting (the subject) in suffering love and identification with those marked out as sub-human by the powers that be, and thus said to have been abandoned by God.

I remember seeing the sacrificial pyramids and temples in Mexico last year. The victim ascended a mountain of steps up to a distant god. In Christianity, God descends to us, to the depths of the human condition.

Another great quote:

“One of the simplest ways of understanding the death of Jesus is to say that when we look at the cross, we see what cost God to secure our release from Sin.”

Sin is understood here not so much in the plural, i.e. sins, but singular, Sin. A condition and as a power which holds humankind in thrall and bondage. If you doubt that, check the news.

And another:

“The paradox of the cross demonstrates the victorious love of God for us at the same time that it shows forth his judgment on sin.”

To put a finer point on the latter element, Jesus was put to death by the combined powers of state and religion. Who killed Jesus? We did. We humans did.

Fleming also devotes extended attention to what she terms, “The unpopularity of self-sacrifice in today’s culture.” She suspects this is because we tend to see self-sacrifice as a form of weakness (an increasingly popular view in post-Christian America, now shared and sanctioned by our highest authorities), rather than an alternative form of power (as demonstrated in, e. g., the Civil Rights movement).

In this connection I’ll quote one final section, which she begins by referring to Dorothy Day, the founder of The Catholic Worker” movement.

“The important distinction is that Dorothy Day’s commitment to a sacrificial life arose from a place of strength, not a place of weakness. Such a life, rightly understood, is uniquely empowering because it is aligned with the self-giving of God in Jesus Christ. Wherever there are gracious acts of unselfishness, there are signs of God’s kingdom of remade relationships based on mutual self-offering.

“Even in this old world ruled by Sin and Death, who would want to live a life of utter selfishness? To show any sort of care for others at all, some sort of sacrifice is necessary every day — to be magnanimous instead of vindictive, to stand back and let someone else share the limelight, to absorb the anger of a teenager in order to show firm guidance, to be patient with a parent who has Alzheimer’s, to refrain from undermining a colleague, to give away money we would like to spend on luxuries, to give up smoking, to bear with those who can’t give up smoking — all such things, large and small, require sacrifice. What would life be without it?”

I hope this whet’s your appetite for tuning in next week.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

"I want to hear God say, "I'm sorry."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

For Lent, I am preaching a series on the Sorrows of Mary. This past Sunday I preached on the Slaughter of the Innocents and attempted to take seriously the claims in the New Testament that the Incarnation is complete only when Christ is all in all things, including the creature we call time. The belief, held by many if not most Christians, that the gospel promises no matter how traumatic and terrible life is and has been, in the End, it will be ok is simply not good enough good news to honor Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim.

If Jesus reveals both the principle of creation and the Father’s own heart, then Revelation 21.4 must prophesy neither the cessation of wounds nor the amnesia of sins suffered but rather the transfiguration of time itself.

Quite simply, I think the New Testament dares us to take the proclamation of rectification literally and apply it more cosmically than we can begin to conceive. And of course, as items within that cosmos we’re perhaps not in the best position to assess what is “natural” or possible for God. Not only do I think the scriptures demand such a conclusion, as a workaday pastor my moral intuition tells me I should have indeed gone to law school if this is not so. I have encountered too many tragedies in twenty-five years of ministry, thrown dirt on too many 2’5’’ coffins— ingested far too much chemo-poison— to celebrate a more meager promise as “good news.”

For example, I have been podcasting for ten years now— I started after my first bout with the cancer that has once again upended my life and depressed my odds in the futures market. In all that time and over so many conversations, I remain haunted by the last response Jason Jones gave to me for the final question:

“What do you want to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?”In his memoir, Limping But Blessed: Wrestling with God after the Death of a Child, Jason Jones discusses his struggles with faith after the loss of his son Jacob in June of 2011. In our conversation with Jason he opened up about his darkest days, bargaining with God, and how he is moving forward since.

I believe I have heard no holier or more righteous statement than the answer Jason gave to that query.

Listen to the episode.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 17, 2025

Is the Cross a Penultimate Good?

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

In my sermon this Sunday, I lifted up the promise, especially prominent in the epistles, that the purpose and end of creation is incarnation, for Christ to be all in all things.

If incarnation actualized throughout creation is its ultimate good, is crucifixion a penultimate good?

In confessing the true God to be the “creator of heaven and earth,” the dogma of the church makes a claim about the present as much as the past. As I’ve written before, the Book of Genesis makes the world’s dependence on God be independent of the difference between one moment of created time and another. God now commands everything in existence to exist. This means that what God creates is not a thing— a cosmos— but a history. God does not create a world that thereupon has a history. He creates a history that is a world, in that it is purposive and so makes a whole.

The cross is a part of the history which God creates. Is it history’s purpose?If creation is good and if its purposive good is Jesus’s Resurrection, then this implies that the Crucifixion is also a penultimate good. Likewise, if the cross of Christ is for sin, then, as conceptually and morally unimaginable as it might be, it appears that creation’s fallenness, its sin and evil, is also an intermediate good.

March 16, 2025

Nothing Has Yet Happened Simply Because It has Passed

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Matthew 2.13-21

Yesterday we wept in the face of death and we marveled at what God has done to death in Jesus Christ. Not only did Jack Underhill claim that Annandale had “the sexiest pastor’s wife in the United Methodist Church,” Jack wrote a poem nearly every day of his life. Jack loved good food and good wine, and when Jack had imbibed too much of the latter Jack would break out in a dance that was “all elbows.”

Those are the sorts of behind-closed-doors details I have the privilege to overhear when I plan a funeral service with a family.

Usually.

But not always.

Or not always at first.

A couple of years ago, a recent retiree from USAID called the church to inquire after a pastor to conduct a graveside funeral for her husband.

“I attend service every so often,” she told me on the phone, “you’re my preacher even if you don’t know it.”

I did not recognize her name, but when she came to my office to plan her husband’s burial I knew her face. On the Sundays when she attended worship, she always sat in the back of the sanctuary. And every time she came forward to the altar for the Eucharist, her face was so wet she looked like her eyes had been baptized. Receiving Jesus in her hands and on her lips, she would then kneel at the altar rail, slumped over it as though from exhaustion as much as in prayer.

She sat down across from me. I opened my notebook, uncapped my pen, and wrote her husband’s name at the top of a clean page, prepared to note the stories and details and memories she would share.

Instead she pulled a hymnal from a purse overflowing with crumpled tissues, “I liberated this from the sanctuary.”

She opened it up at the page she had bookmarked and handed it over to me. It was page 870: A Service of Death and Resurrection. She had circled parts of the liturgy in pencil— the Word of Grace, the Opening Prayer, Psalm 23, and the Prayer of Commendation.

She had scratched through “Prayer of Commendation” and written beside it with an exclamation point, “Prayer of Condemnation.”

I looked up from the hymnal.

“Those,” she said, “Just do those. It’s best if you don’t say anything about him.”

There were no flowers a few days later at Fairfax Memorial Park. There was no portrait of him. There were only a few mourners. After I had presided over the pieces of the liturgy she had requested, she insisted that she and her sister remain at the graveside until the undertaking was finished.

“I won’t be able to rest until I see him surrounded by dirt.”

It always takes longer than people expect.

As the gravediggers neared the end of their task, she turned to me and shot me the same piercing, quizzical look I’d seen in the sanctuary.

“Do you believe in hell?” she asked me.

“Only when people ask me questions like that,” I started to mutter, but when I looked at her I could tell something more than speculation was at stake.

“I can’t help but wonder why you want to know,” I replied.

“Because I lived with him longer than I should have,” she said, “and if he is in heaven, then I don’t want to go anywhere near it.”

I nodded, the puzzle pieces falling into place.

Her sister put an arm around her, “It’s over now; it’s all in the past.”

The widow looked at me and said, “He first hit me on our honeymoon and he never stopped. His words were such I almost preferred his hands. Pastor, I’ve already been through hell. Heaven would be more of it…”

And she nodded at the bare rectangle in the earth, “…Heaven would be more hell if he is there.”

King Herod killed three of his own sons— and his wife— in a mad and jealous drive to protect his throne from usurpers. King Herod’s paranoid rage was so widely known that Caesar Augustus once joked, “It is better to be Herod’s pig than his son.” It is therefore shocking but not surprising that Herod reacts to the magi’s betrayal by dispatching his storm troopers to murder Mary’s boy in the most infallible way possible— the wholesale slaughter of every male in the region of Bethlehem just old enough to be getting their second molars.

The church’s ancient liturgy puts the number of children killed by King Herod at fourteen thousand, a reasonable estimate given that Bethlehem is only nine miles from Jerusalem.

Foreknowing Herod’s plot, the angel of the LORD commands a reverse exodus, ordering the Holy Family to flee— back through the Red Sea— into Egypt. Thus does Mary enact the song she had sung upon the annunciation. She who was rich and filled with good things— very God from very God— is brought low in spirit and sent empty away into Pharaoh’s land.

Being a congenital contrarian, I preached on this passage for Christmas Eve a few years ago. Maybe you remember it. Perhaps you’re still recovering from it. After the seven o’clock service, when the candles had all been blow out and the lights turned back up, one of you approached me at the altar. I could tell from her countenance that, without intending it, I had ruined her Christmas.

She wasn’t angry, exactly.

She was troubled.

“If Jesus dies for his enemies,” she broached, “if Jesus is willing to die for the ungodly like you’re always preaching, then surely Jesus would rather not be born if his birth meant the murder of all those children. Not to mention the trauma to all those mothers and fathers. If those details matter only to me…if they don’t matter to God, then…”

She trailed off, hesitant to voice the obvious conclusion.

I offered her an apparently inadequate response because when I got home half-past midnight after the final Christmas Eve service, she had sent me an email. It was blank save the sentence in the subject line, “Why would Mary say “Yes” to being God’s heaven if it meant hell for so many others?”

And she was right to push back and question, question God.

After all, what does Mary carry in her womb if not the criterion by which we can judge all things, including his Father?

In an essay for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, my former teacher David Bentley Hart attempts to put skin on the subject matter by beginning with a story.

He writes:

“My friends’ son recently had been diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome. As tends to be the case with many children classified as “on the spectrum,” he was often intensely sensitive to, and largely defenseless against, extreme experiences, including moral dissonances.

So it should have surprised no one when he fell into an extended period of panic and depression, after a guest preacher visiting his parish happened to mention the eternity of hell in a sermon. The boy's reaction was one of despair.

All at once, the boy found himself imprisoned in a universe of absolute horror, and nothing could calm him until his father succeeded in convincing him that the priest had been repeating lies whose only purpose was to terrorize people into obedience.

This helped him regain his composure, but not his willingness to attend church; if his parents so much as suggested the possibility, he would slip into a narrow space behind the balustrade of the staircase where they could not reach him..”

Having told the story of his friend’s boy, David Bentley Hart then characterizes the notion that God will contentedly allow a remainder of his creatures to suffer eternal torment— he calls such a notion “spiritual squalor.” And then he adds, “Another description for a “spectrum” child’s “exaggerated” emotional sensitivity might simply be called “acute moral intelligence.”

Here is my question.

If we accept his premise that the torment of even a single one of the LORD’s creatures in eternity is “spiritual squalor” and unworthy of the Goodness of God— if we accept that premise, and I do— then what do we say about torments not in eternity but in time?

If the sorrows and the sufferings of the past simply perdure without rectification, do they not stand as a demonic testament to God’s failure to finish the good work he began in you? If past traumas and historical tragedies stand forever opposed to God, then is not God’s goodness eternally compromised by a deficient almightiness?

As the church father Maximus the Confessor puts it, “Nothing has yet happened just because it has passed.”

Nothing has yet happened just because it has “happened.”

In other words—

Many items of history are thus far not true events.

That which has happened is still unfinished.

Much of what is in the “past” is not yet God’s creation.

Yes, the claim contorts and confuses our sense of time; nonetheless, it is the clear and straightforward assertion of the scriptures. To corroborate the claim, you need look no further than Mary the Mother of God.

Seldom do we pause Christmas pageants to ponder the peculiar detail, but in the Gospel of Luke, the angel Gabriel addresses Mary, “Hail, full of grace, the LORD is with you.” The angel acknowledges her status again two verses later. Biblically speaking, grace is neither a generic term nor a nebulous energy. All grace flows from Christ’s obedience unto death— “even death on a cross.”

Chew on the mystery.

At the Annunciation, the angel addresses Mary as a recipient of the very grace won by the merits of her son on the cross. Again, grace is reckoned to human creatures only on account of Christ’s work on the cross—a temporal event. The grace which fills Mary is a grace that requires Christ’s own faithful life, passion, death, resurrection, and ascension. Yet somehow Mary is a recipient of events which will transpire in the future.

Mary’s status (“full of grace”) is an effect of a cause that would not occur for another thirty to thirty-three years. And yet it was this very effect, this entirely salvific grace, which created a necessary condition for Mary to consent to Christ’s own conception in her by the Holy Spirit. Mary’s “Let it be with me according to your word” was itself made possible by her Son’s consent to the cross in the Garden of Gethsemane.

We think of time as events in a fixed, unalterable sequence. This is not how the scriptures conceive of time. As Jordan Daniel Wood writes, “The incarnation of the Son is an event whose intelligibility requires us to think beyond the serial logic of time.”

Mary is but one example of how the scriptures trespass our sequential logic.

It is all over scripture.

It’s what the Gospel of Matthew shows you when he reports that at the crucifixion when Jesus cried his last and surrendered his spirit, the bodies of Old Testament saints were raised from the dead. It’s what the Book of Hebrews tells you when it proclaims that Christ’s sacrifice is effective backwards through time. It’s what Ephesians proclaims straight out of the gate: Christ Jesus chose us— when— before the foundation of the world. It’s what we pray every time we pray the prayer Jesus so commanded, “…on earth as it is in heaven.”

Make time and eternity rhyme.

If we did not believe God happens to time in such an odd manner, then, as Paul insists, we would still be in our sins. After all, what is faith but trust that a past temporal event somehow redounds down the timeline into the future in order to benefit you?

As Christmas Eve turned to Christmas Day, I wrapped my wife’s presents while I watched Bad Santa. When I was done, I threw back the last of my drink and I picked up my phone and I typed a quick reply to her question, “Why would Mary say “Yes” to being God’s heaven if it meant hell for so many others?”

“Because,” I wrote, “Not only did the LORD choose his Mother out of all the available contenders across time, unlike all other soon-to-be parents his Mother knew the child she would give to the world and, therefore, she knew that he will in the fullness of time transfigure every hell into heaven. This is why Christians have so often spoken of heaven as the Fulfillment with a capital F.”

Mary is the rule not the exception. She is the harbinger of your destiny. The coincidence of opposites in her (a finite creature containing the infinite God) scripture says that is your future too. And not simply our destiny, it is God’s providential desire for every part of creation. Again it is the clear and straightforward claim of the scriptures.

God set Jesus as a plan for the wholeness of time, to unite all things in Christ.”

That’s Ephesians 1.10.

“In Christ all things hold together…” Paul writes to the Colossians, “And Christ is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; so that, he might pervade all things. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things.”

Not all people!

All things.

“The kingdom of God is not coming in ways that can be observed,” Jesus says to the Pharisees.

Why cannot it not be observed?

Because it will pervade all things.

“The Kingdom of God will be inside of you,” Jesus tells them.

Paul echoes Christ’s teaching, writing to the Corinthians that when the incarnation is complete “Christ will be all in all things.”

Jesus will be all in all things. That is, all things will be made like Mary. All finite creatures will contain the infinite God.

And do not forget: one of those things is time.

God creates not simply light but the first day. He makes man and woman but also minutes and moments. Every single instance of your life is as much God’s creation as a tree or a bird, a quark or an atom or my words to you right now.

History is every bit the creature made by God as a hippopotamus.

Thus every moment in time has a divinely-willed end. Every moment of history has a goal which God desires. This demands you remember a basic tenet of the faith: God wills only goodness and love; God wills neither sin nor suffering.

Trust me, I know what it’s like to wonder, “Why are you doing this to me God?!” Despite my faith, I utter it about four times a day, every time I swallow my chemotherapy. I know what it’s like to wonder, “Why are you doing this to me God?!” But guess what— this is why you need a preacher—because he’s not!

He’s not.

God wills only goodness and love.

God wills neither suffering nor sin. Evils are not creation. Sin is not a thing but an absence. Tragedies are not real expressions of God’s will. Traumas are not true events; they are disfigurements to God’s time. And so long as they abide, history is not yet creation— that’s St. Gregory of Nyssa.

Once again:

Time is a creature of the God who wills only goodness and love.

Time is one of the “things” in which Christ will be all.

Time for all us presently contains more moments of pain and suffering than we dare to share.

Just so, the promise.

That part of time we call the past is itself a part of the creation groaning in labor pains, waiting for it to be made whole. This is precisely what the LORD announces from heaven’s throne to the prophet John, “Mourning and crying and pain will be no more.”

How?

Because the minutes and moments that produced mourning and crying and pain will be transfigured. “Those former things,” the LORD says to John, “will pass away.” That past will pass away. It will be undone. It will be transfigured. And only then will creation be creation.

Nothing has yet happened just because it has passed.

Paraphrasing the church fathers, Jordan Daniel Wood writes, “God will transfigure the wills of every participant in every event at every moment of time in order to make these real events, to make them what God has beneficently and lovingly willed for them to be from eternity.” Or as Maximus the Confessor puts it, “For the Word of God and God wills eternally to accomplish the mystery of his incarnation in all things [including time].”

If Mary contains in her belly the criterion by which we can judge the goodness of all things, including God, then anything short of the promise of time’s transfiguration is not a gospel worthy of her son.

I had nearly made it back to my truck where it was parked on the path that snakes its way through the cemetery. She had a hand on the handle of the passenger door of a blue Toyota Camry when she said with great volume and not a little irritation, “You never answered my question, Pastor. I can’t stand the thought of heaven if it means he’s there.”

I nodded. She stood by the car. Her face told me her gas would go bad before she’d leave without a response.

So I said, “The promise of the gospel is that when you enter into heaven, the man you will meet there will be different than the man you knew. For that matter, you will discover the two of you had a marriage made altogether different than the version of it you just buried. Your wounds and your memories won’t be healed; your whole timeline will be transfigured according to God’s will for it.”

She shot me that same piercing, quizzical look I’d seen in the sanctuary.

I added, “It isn’t just that you had hopes for your life and marriage. God does too. And I can’t explain it exactly but somehow God’s going to get what you both want.”

“Why didn’t you say anything like before now?”

“You would only let me do the parts you’d circled, remember.”

“Are you a smart-ass to everyone?”

“No,” I lied.

But if that lie constitutes a sin, then one day, somehow, I didn’t.

What Maximus the Confessor calls “the cosmic mystery of Christ” is the promise that God is at work in Jesus Christ to heal your whole timeline, to mend everything that is broken, every wrong you’ve wreaked, every trauma you’ve suffered, all the tragedies you’ve doom-scrolled— without undoing you, all of it will be undone.

Transfigured according to the LORD’S love and goodness.

Christ will be all in all things, every minute and moment.Such that somehow in Bethlehem beside the magi gifting their frankincense, gold, and myrrh will be Herod, on bended knee and joyfully offering the child his crown.Time will be transfigured.

I know it sounds impossible.

I know it lands as incomprehensible.

Then again, on Holy Thursday Jesus institutes the Eucharist. He distributes the bread and the wine, bidding his disciples to consume them as his own broken body and shed blood.

There and then they are that!

Even though he will not suffer until Friday afternoon.

Even though he will not be raised until the third day.

Even though he will not ascend to the Father until fifty days thereafter.

All of which, Paul writes, are the necessary preconditions for Jesus’ presence in loaf and cup on Thursday night.

Listen, I tell you a great mystery!

All events, A-Y, precede the final Event, Z, when Christ will be all in all things. And yet, Z is the very ground and destiny of every event that came before it.

In case that’s not clear to you, come to the table.

That the loaf and the cup are his body and blood is but a reminder that time doesn’t work the way you think, and therefore not only your future but your past and your present are all far better than you ever dared to imagine.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 14, 2025

The Whole Mystery of Christ

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

In ten years of podcasting, there is only one guest who has gotten more listener requests than Jordan Daniel Wood (looking at you, Rowan Williams).

I have benefited greatly in my faith and vocation from Jordan’s work. I first encountered Maximus the Confessor as an undergraduate and his intuitions about the gospel still strike me as right and righteous. I’m grateful for Jordan’s work to unpack them with a clarity and passion that ventures into proclamation.

Check out his book here.

Thanks to cancer and our producer, Tommie, getting a real job the podcast has been on an unintended hiatus for several months. We hope to remedy that pronto.

Show NotesSummary

In this conversation, Jason Micheli speaks with Jordan Daniel Wood about his journey into the Christian tradition, particularly through the works of Maximus. They explore the implications of the incarnation, the nature of creation, and the goodness of God in relation to evil. The discussion also touches on the importance of time, perfection, and the legacy of the Church Fathers, as well as the challenges of teaching theology in a modern context.

Takeaways

Jordan Daniel Wood is a prominent figure in contemporary theology.

His journey into the Christian tradition began with a focus on scripture.

Maximus has significantly influenced his understanding of theology.

The incarnation is central to understanding creation and God's will.

The goodness of God is a crucial theme in addressing the problem of evil.

Time is seen as a dynamic aspect of God's creation.

The interconnection of all creation reflects God's infinite goodness.

Teaching theology requires engaging with students' doubts and questions.

The Church Fathers offer rich insights that are often overlooked today.

The legacy of the Church Fathers continues to shape modern theological discourse.

Titles

Exploring the Depths of Christian Theology

The Influence of Maximus on Modern Thought

Sound Bites

"You're the most number of readers I need to talk to."

"His actual text was enough to convince me."

"The word became flesh and the flesh was hers."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 13, 2025

WWPD

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

The lectionary epistle for the Second Sunday of Lent is Philippians 3.17-4.1, in which the apostle Paul has the stones to exhort the church to imitate him.

Here is a sermon from the vault, wherein I recall Stanley Hauerwas daring me to imitate him in believing that Jesus makes a difference for all matters that matter. Speaking of Stanley, there is a new devotional collection compiled from his writings.

Check it out here.

March 12, 2025

“Great God Almighty done parted the Red Sea one mo’ time!”

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is the first installment of our study of Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ.

We discussed Fleming’s first motif, Exodus and Passover, and will tackle Blood Sacrifice on Monday.

Show NotesSummary

This conversation delves into the themes surrounding the crucifixion of Jesus, exploring its significance in Christian theology, the implications of justice and sin, and the role of the cross as a symbol of solidarity and shame. The discussion also touches on the concepts of forgiveness, atonement, and the Exodus motif, emphasizing the transformative power of remembrance in the Eucharist and the contrasting narratives of heroism and sainthood in Christianity.

Takeaways

The crucifixion is central to Christian faith and theology.

Fleming Rutledge's book offers deep insights into the meaning of the cross.

The cross symbolizes both shame and solidarity with the outcast.

Forgiveness in Christianity is costly and not simplistic.

The Exodus story is foundational for understanding salvation.

Remembrance in the Eucharist is an active participation in God's grace.

Christianity often contrasts the narratives of heroes and saints.

The cross challenges cultural notions of power and success.

Justice and sin are intertwined in the context of the cross.

God's initiative is central to the story of salvation.

Sound Bites

"The cross is a problem for many people."

"God is on the move."

"The main actor in a saint story is God."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 11, 2025

On the Doctrine of the Atonement

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber!

Last night we began our study of atonement motifs in Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ. During our discussion, I mentioned Robert Jenson’s creative assertion that the church’s only ecumenical explanation for the triune God’s work in and through the cross is the Easter Vigil’s performance of the scripture’s redemptive plot.

Here is an essay by Jens, published by the Center for Theological Inquiry where I once delivered his mail to him and where he served as the director at the end of his career.

On the Doctrine of the Atonement

By a “doctrine of atonement” we conventionally understand an account of why Jesus’ death on a Cross is important to us, and specifically for our relation to God. Notoriously, “atonement” is a deliberate coinage - though an old one, documented to 1513 - meaning the act of putting things at one, particularly where a previous unity has been broken. The word in its theological use thus presumes that what happened at Jesus’ death was a reunion between God and us - which seems a biblically sound assumption. A doctrine of atonement is then an attempt to say how Jesus’ crucifixion does that.

It is a commonplace to observe that there is no dogma of atonement. Although, in Christology there is dogma established at all seven ecumenical councils, no council - or pope or other plausibly ecumenical authority - has ever laid down a dogma of atonement. If you deny that Christ is “of one being with the Father,” or that the Son and Jesus are but one hypostasis, you are formally a heretic. But you can deny any offered construal of how the atonement works, or all of them together, or even deny that any construal is possible, and be a perfectly orthodox believer. To be sure, if you simply deny that Jesus’ death does in fact somehow reunite us with God, you are no Christian at all, but that is a different sort of deficiency.

Indeed, not even informally is there a generally accepted proposal. There is a instead an inherited heap of proposals, classically if somewhat heavy-handedly and prejudicially sorted out by Gustav Aulèn in his immensely influential Christus Victor. To be sure, in the West, Anselm of Canterbury’s proposal - or rather a perversion of it - is often called “the doctrine of atonement,” but if we look to the full ecumene we observe that this identification is mere provincialism, Anselm having had at best mixed reputation in the East.

Now, some make a virtue of this proliferation of proposals and the absence of formal or informal consensus around any one of them; others see in it an historical failure and a challenge to do better. I am among the latter - which may be unwise, but there I am.

Those who make a virtue of our historical irresolution often say that the atonement at the Cross is so profound a mystery that it can only be evoked by heaping up tropes. So it will be said that Anselm, with his “objective” doctrine, and Abelard, with his “subjective” theory, and the ancient fathers who spoke of Christ as Victor over Satan and his powers - and any further contributors one might find - were not in fact doing what they each thought they were doing, providing a conceptual account of the Cross’ atoning efficacy, but rather were putting forward “images” of what happened on the Cross; and that now looking back we should say that this is just fine, indeed that the more such images heaped up around the Cross the better. The language of “images” has even become a standard way of referring to doctrines of atonement.

This move has its attractions, and folk I respect make it, but I have to say that so soon as someone begins to talk about something being just too mysterious to talk about with concepts, I get nervous - images have their own grip on reality and are indispensable, but proposing to get along only with images is problematic. True “mysteries” in the biblical use of the notion indeed often break our concepts, and may even confront us with truth whose conceptual description obeys Gödel’s maxim, but mysteries in the biblical sense do not reduce us to exclusive reliance on images. Thus the Incarnation is indeed a mysterion , in that it is in itself an irreducible contingency, transforms other reality, and is to be known only if God reveals it - and I have just recited three perfectly conceptual and coherent things theology has said about it. So also the Cross as atonement is a mystery in that proper biblical sense, which by no means entails that we are excused from clear conceptual discourse about it and indeed about its mysterious character.

Thus I am instead inclined to say that the historical record simply displays a theological question which we have so far not been able to answer in a fully satisfying way - which would, after all, not be the only such case. The notion that Anselm and the Fathers and the rest were proposing not theories but images or metaphors, and that the more of these we heap up the more we celebrate the mystery, seems to me a rather plain case of making a virtue of a failure. And I am even so rash as to think I have a diagnosis, that I know why the church’s thinking has so far failed at this point.

So my first endeavor will be to present my diagnosis. Very early, Christian theology of the Cross made two paired errors - which are of a piece with wider error. The Bible makes sense of the Cross by narratively and rhetorically locating it in the total history the Bible tells, and by conceptualizing the linkage. The twin errors I am about to discuss did their damage in concert by together cutting out the event of the Cross from its location in the biblical story.

The one error cuts the Cross off from its future in the Resurrection - without which, in the Bible’s general view of reality, a crucifixion would be anything but beneficial. The pattern of the primal kerygma of atonement is displayed in Luke’s presentation of the first Christian sermon: This Jesus you put to death by the hands of sinful men, but God raised him up; and therefore return to God, life in his Spirit, etc., are open to you. But this is not the pattern of our inherited post-biblical theories - indeed, so much is this the case that when theologians steeped in one of the inherited theories encounter this primal biblical doctrine outside the Bible, they sometimes do not recognize it.

The other mistake was to sever the Cross from its past in the canonical history of Israel. Without its specific location in Israel’s adventure with God the crucifixion of this one provincial celebrity, on suspicion of religio-political conspiracy, would hardly have been noteworthy amid the thousands of such Roman executions, even if he had thereafter “appeared to many.” Nevertheless the inherited theories discuss the Crucifixion in essential abstraction from Israel’s history. It is not surprising that they prove in the long run unconvincing. I will discuss these two ancient theological disasters in the order just laid out.

First then, the separation of atonement and Resurrection. In one way or another the historically inherited theories of atonement presume that the action of atonement is finished when Jesus dies, so that the Resurrection then accomplishes something else, if indeed often no more than to repair collateral damage done by the Crucifixion. Anselm’s doctrine is perhaps the most notorious in its ability to do without the Resurrection.

Anselm is, of course, regularly denounced on other grounds. Before proceeding to my own critique, fairness compels me to come to his defense. Many of those who attack - or affirm - “the Anselmian theory of atonement” do not seem to have read his text. Anselm does not say that Jesus’ death satisfies God’s wrath, or that God punishes Jesus instead of us. Quite to the contrary, Anselm presents Jesus’ death as God’s rescue of creatures who are on a self-destructive path, which God accomplishes by averting a regime of punishment and instituting instead a regime of repair.

Nevertheless, Anselm’s doctrine does have a fatal flaw: the Resurrection is not integral to the achieving of this result. Both in Anselm himself and in the bowdlerizations of Anselm which are presented as “the” doctrine of atonement, God and humanity are reconciled when Jesus dies; the Resurrection simply tidies up. It is very likely that Anselm himself as a devoted reader of Scripture and as a bishop a regular celebrant of Eucharist simply assumed that nothing theological interesting works without the Resurrection; however his theory does not incorporate this.

To grasp the second founding error, we should remember that aforementioned exegetical commonplace: that the Gospels’ own interpretation of the Cross consists for the most part in embedding it in the Old Testament narrative. As is well known, hardly a detail of the Gospels’ passion-narratives fails to invoke some Old Testament text or event. And Pauline and Johannine theology explained the meaning of the Cross with Old Testament concepts, used in their original sacrificial and eschatological force.

But post-apostolic Christian theology quickly isolated the Cross from its biblical embedding in Old Testament discourse at the dogmatic level, if not in preaching or always in the liturgy. Both the early rules of faith and the baptismal and conciliar creeds that developed from them skip straight from Creation to the Incarnation, leaving out the whole of the Lord’s history with Israel. To be sure, Marcion’s proposal to reject the Old Testament’s God altogether was too much: it was immediately seen that the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ had to be the Creator, so creation got in. But for all the creeds display, the Creator could just as well have sent his Son to reunite humanity with himself without having called Abraham, or having led Israel from Egypt, or having dwelt in the temple, or having sent Israel into exile and having brought them - sort of - back, or indeed without having done any of the works told in the Old Testament after the first chapter of Genesis. Think how the Roman creed goes: “I believe in God the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth. And in Jesus Christ....”

The omission is not accidental or explicable by circumstance, for it has been pervasive in other central aspects of the church’s life and theology, not just in the creeds. For a central location in the life of the church, closely parallel to creedal formation, the Lord commanded us to give thanks to God in the style of Israel’s table-thanksgivings, sharing in the thanksgiving by sharing bread and cup, again in Jewish style. And most sorts of Christians have more or less obeyed. But what we have given thanks for has routinely omitted the Exodus and the giving of Torah and the sending of the prophets, and indeed everything that must have figured in the Thanksgiving Jesus himself offered. Most - not all - eucharistic prayers mentioned creation and the fall - which last, I suppose, is some improvement over the creeds - and then went straight to Jesus and his Cross.

As to systematic theology, many powerful systems make no use at all of the Old Testament except as witness to creation and sin, and as religious background for Jesus.

The systems of classical liberalism, fragments of which still dominate in this country, often do not even do so much. Indeed, classical liberal theology was in some part powered by desire to detach Christianity from the Jews and their Scriptures.

This isolation of the Cross from the biblical history by which the Gospels and the rest of the New Testament make sense of it - from the Resurrection in one direction and from God’s history with Israel in the other - has inevitably compelled theology to find some other framework within which to make sense of the Cross. If we come to the Gospels without an antecedent theory, what do we actually find told about the Cross? The Gospels tell of a Jewish prophet and rabbi executed by Jewish and Roman authorities, because he proclaimed and enacted the Kingdom with utter immediacy, and so “made himself the Son of God,” which for the Jews meant blasphemy and for the Romans translated to “pitiful would-be rival to the Caesar.” And the biblical witnesses interpret that mostly by the way they tell the story as an event connected within a longer story. They do so in the one temporal direction by telling of this event as an event within the whole scriptural history of Israel, and in the other direction by trumping and concluding the story of execution with the message of Resurrection. Our inherited theologies of atonement, however, having severed these connections, must imagine some other framework and some other event within it.

So Anselm imagined a universal feudal system - in which the good of each personal member is invested in the mutual giving of honor where due -that construed sin as disruption of the universal balance of honor, and, construed the atonement as creatures’ rescue from disaster by God’s restoration of the balance. I do not say that the doctrine which resulted is altogether false or that one cannot in some contexts make use of it. The vision is detachable from feudalism and bears consideration for its own sake. But it remains that Anselm’s transaction of honor as imagined has little resemblance to the story narrated in Scripture, and that a free-floating imagination of this sort is indeed apt to become one trope among others to be piled at the foot of the Cross.

So Abelard imagined a universal divine moral pedagogy aimed at educating moral creatures in virtue, particularly in the virtue most lacking among fallen creatures, love. Then Abelard construed the Cross as the overwhelming display of God’s love, which breaks our hardened hearts and moves us to love in response. Again, I do not say there is nothing in this, only that it is again the imagining of an event other than the one the Gospels narrate: indeed, an evocation of love that could have been accomplished by some other event altogether than the Cross, and even within the history of some other nation than Israel. Therefore in the long run it will work out as indeed just a nice metaphor to heap up with others around the Cross.

Most of the Eastern fathers imagined - not to put too fine a point on it - a myth. Consequent on the fall of certain angels there had been, they said, continuous warfare between God and those now satanic powers, of which hidden warfare all the overt turmoil of earthly history is but the heavily veiled manifestation. In this war the Incarnation of God the Son and the giving of him over to crucifixion was a brilliant tactical move by which God gained final victory. Only on the surface was Jesus crucified by Jewish and Roman authorities; what actually happened was an attempt by Satan to kill what he thought was a human savior, who turned out to be God the Son himself, on whom Satan’s power broke.

Now Scripture indeed uses mythic fragments and images in a variety of contexts and ways also in telling of the Cross. But it never tells a whole myth, and not this one. Scripture breaks up eastern antiquity’s mythic world view, retaining some of its bits and pieces for its own quite different purposes. The fathers reversed this and made up a whole new myth from some of those bits and pieces, as the frame within which to understand the Cross. The resultant patristic imagery of conflict and victory is powerful and even spiritually transformative, but theology, born of the urge to demythologize, must eventually come to regard the patristic imagery as indeed just imagery - which of course is how we now actually handle it, even when declaring allegiance to “the patristic doctrine”.

So what must we do instead? A first step is liturgical. We honor the way in which the atoning Crucifixion is indeed a mysterion in the proper sense, when we note that its primal construal is recital and enactment of the passion narrative in and by the liturgical celebration of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil, and by the condensation of that triple celebration in each Sunday Eucharist. We understand the Cross as our reunion with God when we ourselves are made actors in the Cross’ story, a story which in the ancient three-day celebration is indeed complete with Israel and the Resurrection. The traditional liturgy of the three days incorporates us into the action by repeated communion, narrates in the readings and prayers Israel’s complete history, and allows no conclusion, no benediction, until the Resurrection has been proclaimed.

It is undoubtedly this liturgical sequence transcending the limitations of the creeds and of the doctrines taught in school that kept understanding of the Atonement alive for so many centuries. And I suggest it is the loss of this liturgy in most of Protestantism, and the concurrent loss of its Sunday compendium, that has slowly but at the last inevitably delivered Protestantism over, on the one hand, to the grotesqueries of “blood atonement” and the like, and, on the other hand, to a doctrine of atonement which may be summarized: God loves us all regardless, and now let’s get on to the real issues of peace and justice.

But I have treated of the liturgical knowledge of atonement in my Systematic Theology . Here I want to consider something else, I want to develop a theoretical construal that in the systematics appears only in nuce.

A doctrine of the atonement is supposed to conceptualize our reunion with God. What needs to be done - a work which is hardly begun in the Systematic Theology - is to show how the event of the Cross, taken with its biblical past and future, does this. An attempt at this will make the last part of this lecture. What is needed is a conceptual framework which does not substitute for the biblical history, but rather exemplifies it. Just such a framework is at hand.

It is the triune God with whom we need to be reunited. Trinitarian doctrine’s statements of relations that make up the life of this God - that the Father begets the Son and breathes the Spirit, that the Son is begotten of the Father and sends the Spirit, that the Spirit frees the Father and Son to love each other - describe the plot of that biblical story I have been invoking. And trinitarian doctrine’s identification of Father, Son and Spirit as three in God, names the carrying dramatis personae of that story.

Thus a particular location within the biblical story is just such a particular location in the life of God, and a particular set of relations to the three divine persons. A construal of how the Cross with its past and future unites us with God must say how this event reunites us in the divine life with each of these divine persons.

For we can be reunited with the triune God only as we are fitted into the triune life. With some other sort of God matters might stand differently. But the biblical God is no sort of monad; we cannot be reunited with him as one might reunite two pennies by stacking them, or even as one might reunite two created persons by negotiating their alienation. Nor can the specifically triune God sustain any merely causal relation to the world, in any current use of “causal”; he cannot reunite us with himself by working on us to change us. The relation of creatures to this God is always their involvement with the three who are God - or an abysmal possibility, their disinvolvement.

So we must go triune person by person-remembering always that the kind of discourse that follows is a kind of sloganeering, that “the Father” is the God of Israel, that “the Spirit” is the power of Resurrection, the power of God’s future, and that “the Son” is the Son Israel was called to be and who in the Resurrection is that totus Christus that includes us. If this is not remembered, it may appear that in the following I do what I have rebuked the tradition for doing, replacing the biblical narrative by a framework invented by theologians.

We need to be reconciled to the Father, and are, in the Son by the Spirit - and here and in the following readers should pay heed to the play with prepositions. We need to be reconciled to the Father because we are at odds with him, at odds with the very one by whose sheer will we exist. That is, we are in rebellion against the Torah which tells us of the Father’s will - it is in this patrological connection that talk of disobedience should appear in our doctrine of atonement. The Spirit - here the Spirit is the agent - reconciles us to the Father, by making us one moral subject with Christ, who on the Cross is obedient to the Father, even unto death. As both Luther and Jonathan Edwards taught, the Spirit so unites us with Christ that the Father’s judgment, “You are righteous,” is not fiction or a legal maneuver, but a judgment of observed fact - observable, to be sure, only by the Father. And it is by Cross and Resurrection that the Spirit accomplishes this unity when he enables the Son to cleave to us though we kill him and enables us to cleave to the Son’s risen presence.

We need to be reconciled to the Spirit, and are, by the Son - here he is the agent - before the Father. We need to be reconciled to the Spirit because we have backed off from the fulfillment to which he draws us, we have cowered before the utter transformation to which the Spirit has from creation on prodded us, we have not - in Bultmann’s famous phrase - been open to the future. Thus it is in this pneumatological connection that talk of unbelief should appear in our doctrine of atonement. The Son reconciles us to the Spirit by entering that wonderful and frightening future before us, going through the end of this world on the Cross and entering the Kingdom through the Resurrection, the while appealing to his Father to honor his dearly purchased solidarity with us, as in the Resurrection the Father does. Thus the Son brings us along as he follows the Spirit’s leading. Indeed, as Paul taught, the Son so reconciles us to the Spirit that the Spirit even prays to the Father from within us as so much our own voice that we cannot hear him.

We need to be reconciled to the Son, and are, by the Father, in the Spirit. We need to be reconciled to the Son becaue we have wanted to be individuals - nor is this a uniquely modern rebellion. We have not wanted to be members of one body together, the body of Christ, to have our life within the totus Christus , Indeed and consequently we have not wanted to live within any personal whole other than that which each of us hopelessly tries to make for him/herself - and it is this christological connection that talk of our being each incurvatus in se should appear in our doctrine of atonement. The Father, however, sends the Son into eternal identification with us, even unto Sheol, so that we simply cannot escape being one with the Son and so with one another. And in the Spirit we willingly live that identification, for the members of the Son’s body are also his people and his spouse, which without our will we cannot be.

So we are reconciled to the triune God by acts of each of the three over against the other two. Thus it may indeed appear that we are reconciled to God by his being reconciled in himself - but that is a matter for another essay altogether.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers