Jason Micheli's Blog, page 14

April 3, 2025

"Sacrifice" Does Not Mean "To Kill Something"

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become paid subscriber.

In the rousing eighth chapter of his Epistle to the Romans, the apostle Paul writes, "Who is to condemn? Christ Jesus is the one who died—more than that, who was raised—who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us.” Despite how contemporary Christians in the West isolate the cross as the central salvific event, note how for Paul the crucifixion is but one event in a sequence of events that culminates in the risen Christ’s present-tense, continuous work as our Great High Priest.

The entire sequence of events— not a one of them individually— constitutes the LORD Jesus’ “sacrifice.”The Book of Hebrews, which the church fathers believed to have been authored by Paul, also displays this sequential, cumulative understanding of the atonement. In particular, the concatenation of incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, ascension, and abiding intercession is precisely what places Christ’s sacrifice in continuity with the sacrificial order the LORD first bequeathed to his Israel. As David Moffitt puts it, “Jewish sacrifice consists of an irreducible ritual process.”

April 2, 2025

"To believe in a God who does not intervene in our world is to live a life of functional atheism."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become paid subscriber.

The Old Testament passage assigned by the lectionary for the Fifth Sunday of Lent is Isaiah 43.16-21:

Thus says the LORD, who makes a way in the sea, a path in the mighty waters, who brings out chariot and horse, army and warrior; they lie down; they cannot rise; they are extinguished, quenched like a wick: Do not remember the former things or consider the things of old. I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth; do you not perceive it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert. The wild animals will honor me, the jackals and the ostriches, for I give water in the wilderness, rivers in the desert, to give drink to my chosen people, the people whom I formed for myself so that they might declare my praise.

From the vault, here is an old sermon on the scripture.

“God is in heaven and you are on earth,” laments the author of the book of Ecclesiastes.

God is in heaven, you are on earth.

Maybe sometime.

But not always.

Blaise Pascal was a 17th century mathematician, physicist, and philosopher. A child prodigy, Pascal developed probability theory and projective geometry as a 16-year-old teenager. In other words, Pascal knew how the world works. He understood cause and effect. He practiced the scientific method. He valued the rational mind.

When Pascal died, a piece of parchment was discovered sewn into his coat.

The piece of paper reads:

“The year of grace, 1654, Monday, 23rd, November, from about half past 10 in the evening until half past midnight.

Fire, fire, fire.God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of philosophers and scholars. Certainty, certainty, heartfelt joy, peace, God of Jesus Christ, my God and your God, thy God shall be my God, the world forgotten and everything except God. righteous Father, the world had not known thee, but I have known thee. Joy, joy, joy. tears of joy, everlasting joy in return for one day's effort. I will not forget. Amen.”

Pascal carried the memorial with him at all times for the rest of his life.

Fire. Fire. Fire.

The living God had intervened in his life in a mighty way.

April 1, 2025

We are the Nard God’s Purchased at Great Cost

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

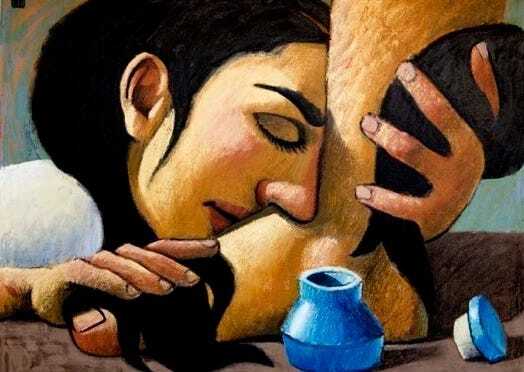

This coming Sunday’s lectionary Gospel is John’s account of Mary anointing Jesus at Bethany. Here’s a reaction Bishop Will Willimon wrote to my sermon on the text for the Journal for Preachers.

John 12.1-8

Thousands of us preachers receive encouragement from Jason Micheli’s podcast, Crackers and Grape Juice. Here’s my commentary on one of Jason’s Christ the King sermons. Take this as two preachers thinking together about the challenges of doing politics in the pulpit with Jesus.

— Will Willimon

For God’s sake, don’t lie.

Admit it. You think Judas is right.

You know that you’re not supposed to identify with Judas the traitor, the villain. Judas is the Judas, the bastard who turns around right after today’s text to rat out Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, which according to the prophet Zechariah was about a day’s wage. A day’s wage.

But be honest. If you saw a line item in our church operating budget for nard you’d be PO’d too. Nard was a perfume from the Himalayas. 300 denarii is what Judas guesses it would go for on the open market. 300 denarii was the rough equivalent to $45,000.00.

You think Judas is right on the money about the money. Considering the cost of nard, it would be better to rub Jesus down with some $5.99 Old Spice and give the remaining $44,990.00 for do-gooding.

And doing good is what it’s about, right?

Way to go, Jason. Lure them into the sermon by claiming their secret sympathy with Judas. Treat ‘em rough.

After all, Matthew’s account of this anointing occurs right after Jesus lays down every liberal Methodist’s favorite parable— clothing the naked, giving drink to the thirsty, feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, and visiting the prisoner. So who blames Judas for wanting to be reckoned a sheep rather than goat?

Matthew 25, favorite text (they think) of all Methodist do-gooders. Nice juxtaposition between Matthew and John. Move them from a text they think they know to consideration of a text they probably don’t know, allowing scripture to interpret scripture.

If we’re honest, it’s hard for us to see what Judas got wrong. Christians ought to be on the side of the poor. The world sees our inability to live up to Christ’s teachings about the poor and judges us accordingly. Isn’t Judas’ the better strategy for the Church to survive in a pagan nation like America? After all, Americans may not believe that Jesus is Lord but they at least believe we ought to help the poor. Serving the poor is a way for us as Christians to win friends and influence people.

Interesting link with the American church’s insecurity about our status in the culture. Why does the mainline church “helps the poor”? Because it’s the last socially acceptable thing the church has left to do.

March 31, 2025

Cancer, Ascension, and the Nones

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

A blessed Lent to you.

Now that I am home from a long and wonderful pilgrimage through Asia Minor, I wanted to catch-up and provide you with a few links that you may find worth your time.

Pastor’s Table PodcastRecently, I was invited to be a guest on the Pastor’s Table Podcast from Northern Seminary in Chicago. The show is hosted by Rev. Tara Beth Leach and Dr. Mark Quanstrom. They titled Part I of our conversation, “When a Pastor Gets Cancer: Jason Micheli on Suffering, Storytelling, and Trusting the Church.”

Check out their show.

Here’s the recording:

Forty Facets of the Ascension— New Book Launch

Forty Facets of the Ascension— New Book LaunchMy friend Sarah Hinlicky Wilson has a Kickstarter running to launch her new book, Forty Facets of the Ascension.

Are you a preacher wondering what on earth you can possibly say new and interesting on Ascension this year—to say nothing of all the Ascensions that lie ahead of you?

Are you a churchgoer curious about this little odd holiday stranded on a Thursday between Easter and Pentecost?

Are you of a scientific mindframe, perpetually stressed out by the thought of Jesus rocketing up to the outer stratosphere like an out-of-control hot air balloon?

If you answered yes to any or all of these questions, then support Sarah’s Forty Facets of the Ascension!

You can find the Kickstarter here. Do it quick— it closes in 37 hours!

Good without God?

Ryan Burge is a professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, and Tony Jones, is a theologian. Both have been guests on my podcast in the past. Tony is a good friend.

Ryan and Tony recently secured a Templeton Grant to lead the “Making Meaning in a Post-Religious America Project.” They have conducted the largest ever survey of those who identify as “None,” and they have invited me to be a part of a small group of interlocutors who will have the first opportunity to digest and respond to their findings.

That work will begin in April in the Twin Cities.

In the meantime, you may be interested in a Wall Street Journal piece they penned, previewing the work:

“The biggest story in American religion is the dramatic rise of the “nones”—people who say they are atheist, agnostic or have no particular religious faith. The nones are currently at an all-time high of about 30% of the population; for Americans born since 1996, the figure is around 45%. Yet it’s striking how little is known about this group. For several decades, social science has been content to lump all 100 million nonreligious Americans into a single category.

That is finally starting to change. Last year we conducted the largest-ever survey of nones, with 12,000 participants. The results challenge the assumption of many religious thinkers that every human being has a deep yearning for God.

In fact, one-third of nonreligious people fall into a category we call the “dones,” because they are finished with religion altogether and want nothing to do with it. Not only do people in this group never attend organized religious services; 88% say they never pray at all. Just 6% of the dones agree with the statement “When I die, I will be reunited with loved ones,” while 77% percent believe that when they die, “my existence ends.”

For the dones, the absence of God and spirituality doesn’t seem to negatively affect their mental health or well-being in any way. The share of dones who agreed with the statement “I feel I do not have much to be proud of” was 20%, statistically the same as among Protestants or Catholics.

Things are different in another group representing about 10% of nonreligious Americans. We call them the “zealous nones,” because they are evangelical about their unbelief. More than three-quarters of this group tried to persuade someone to abandon their faith during the prior year. Unlike the dones, the zealous nones seem to have more struggles with mental health and well-being. They were 13 points more likely than Christians to say “I feel that my life is not very useful.”

But the majority of nonreligious non-Americans have a more complicated attitude toward spirituality. We found that 21% are what we call “nones in name only”: over half of this group says they pray daily, and a third attend some kind of religious service at least once a year. And 66% say they feel drawn toward spirituality but are much more resistant to the idea of organized religion.

There are constant headlines about the rise of anxiety, isolation and mental illness in the U.S., and some commentators point to the decline of religion as a cause. Our research doesn’t exactly confirm that idea. While an increase in religious participation may lead to some positive outcomes, a significant number of people are “good without God.”

At the same time, the majority of nonreligious Americans do yearn for some kind of connection with a higher power. This suggests that a religious revival is certainly possible in the U.S., so long as the nones aren’t seen as a problem to be solved, but a group that needs to be better understood.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 30, 2025

Jesus Saves, Not the Cross

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a cpaid subscriber.

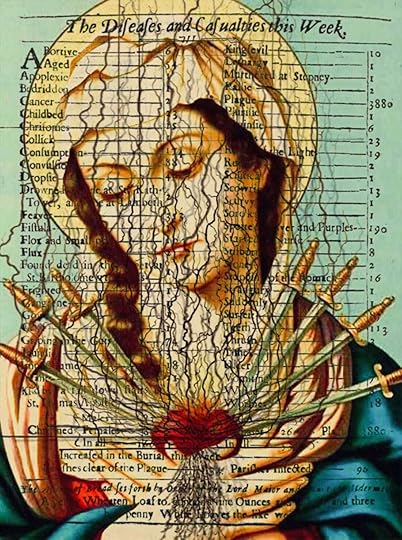

I continued our Lenten sermon series on the Seven Sorrows of Mary with John 19.17-27.

Nine years ago, during the first Trump term, I preached on the scripture assigned to me from the beginning of the Book of Exodus. There in the first chapter of Exodus Moses reports that a new pharaoh ascends to the White House, a president who does not know the previous administration’s advisor— Isaac’s son, the dreamer Joseph. Observing the rapid birth rate of these refugees who’ve crossed over the border from Israel, Pharaoh posits the first great replacement theory. He frets these immigrants will soon replace Egypt’s natural born citizenry. Hoping to induce them to self-deport, Pharaoh first inflicts upon the Hebrew immigrants harsh labor. Later, when harsh labor does not remedy the perceived dilemma, Pharaoh resorts to infanticide, “The king of Egypt said to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, “When you serve as midwife to the Hebrew women and see them on the birthstool, if it is a boy, you shall kill him.”

Armed with such a pregnant passage, I stepped into the pulpit on the twenty-fourth of September and, straightaway into my sermon, I punched down.

No sooner had I engaged in a quick bit of exegesis than I pivoted to the present day, wielding the scripture passage as a pretext to excoriate the new president’s draconian immigration policies. I struck a prophetic posture. I opened the vent on the fire and brimstone. I laid down the law. Specifically, I exhorted my hearers to heed the LORD’s commandment to Moses on Mount Sinai, “When an immigrant sojourns with you in your land, you shall not do him any wrong. You shall treat the immigrant among you as a native-born, and you shall love him as yourself, for once you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” Now notice— in my selective sermonizing I neglected to mention abortion, an issue every bit as front and center at the beginning of Exodus as immigration.

I concluded the sermon with the If/Then, Either/Or conditionality that is the hallmark of the law. And remember— the law, scripture says, only always accuses. The law elicits only the opposite of its intent; it does not create the righteousness it demands. Nevertheless, I mistakenly preached as though my listeners had free will. “Either serve the LORD Jesus Christ and welcome the immigrant,” I preached, “Or ship them out— detain them, deport them, separate them, mother from child— and, by doing so, serve the Pharaohs who crucify the LORD anew.” “Choose this day whom you will serve,” I hollered, “You’re either on the side of the crucified, or you’re on the side of those who build crosses.”

To close, I even borrowed a quote from Peter Marshall’s famous sermon on Elijah versus the prophets of Baal, “Trial By Fire.” “If Jesus be LORD, then follow him,” I preached, “but if the President be Lord, follow him, and go to hell!”

And then I walked out of the pulpit as though it was a mic-drop moment.

Admittedly, in hindsight, it was a little heavy-handed.

But to be honest, initially I judged it a good sermon. Of course, I thought it was a good sermon because my listeners— that is, the ones who already agreed with me on the issue— told me it was a good sermon. A sure sign I had decided what to preach before I ever listened for the Word of God to have its way with me.

In other words, I had attempted to twist Jesus to my own ends.

“Standing by the cross of Jesus were Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene, and his Mother Mary.”

The Mother of the LORD does not ask for the life that alights upon her at the annunciation. Nevertheless, Mary says “Yes” to God”s “Yes” to lost humanity. To the angel Gabriel’s intrusive announcement, Mary replies, “Behold a slave of the LORD; let it be with me according to your Word.” Miraculously— full of grace—Mary manages to say “Yes” to the Triune God’s “Yes” to us. For that matter, Mother Mary seems never at a loss for words. When Mary retreats to Elizabeth’s house to ponder the mystery of the incarnation and thereupon her cousin addresses her, “Blessed are you among all women,” Mary immediately strikes upon words for the occasion. Mary sings, “My soul proclaims the Lord’s greatness, And my spirit rejoices in God my savior…”

When Jesus inaugurates his ministry at a wedding in Cana of Galilee and soon thereafter the father of the bridegroom runs out of wine, Mary does not hesitate. Words do not fail her; immediately she turns to the servants of the host and commands them, “Do whatever he tells you.” When the Pharisees and the scribes up the ante and turn the gears of their plot against her boy, demanding from him a sign, Jesus replies caustically, “A wicked and adulterous generation seeks a sign and a sign shall not be given it.” No stranger to danger, Mary risks her son’s rebuke and intervenes, sending for him to return home.

Once her unasked for life arrives, Mary is no more a passive victim than her boy. At every turn, Mary always knows what to say. Or, not to say.

Not only does Mary say “Yes” to God’s “Yes” to us, Mary does not say “No” to God’s “No” to humanity’s lostness. As Jesus utters his seven last words from the cross, Mary does not offer a single one.Indeed beginning with the day she relinquishes him at temple, handing him over to the Father, the only person to accept Jesus on his own terms is his Mother.On that Sunday in September, Charlotte Rexroad lingered in the narthex after worship.

Charlotte had been the chair of the Staff-Parish Relations Committee when the bishop appointed me to the church eleven years earlier. At the mandated “Meet the Pastor” encounter, Charlotte dressed like Jackie Onassis, wearing a vintage, soft turquoise suit. Soon after, I learned that it was not a costume. Charlotte was proper and dignified and astonishingly empathetic.

After I went on medical leave for my first bout with cancer ten years ago, Charlotte brought me lunch every Wednesday. Every week she made me a homemade Rachel sandwich— like a Rueben but with chicken breast— along with chips, a pickle, and a bottle of Thousand Island Dressing. It was not long before I had more bottles of the salad dressing in my refrigerator than chemotherapy drugs. Charlotte had organized a baby shower when we adopted our first son, Gabriel. Charlotte engaged every Bible study I taught like her GPA teetered on the precipice and a diploma hung in the balance. The Word were words of life for her.

Jesus was as real to Charlotte as the forty-eight bottles of Thousand Island she had brought to my house. She often disaffiliated from women’s prayer circles, chagrined such groups did little actual praying.

If ever I have met a human creature being fashioned into God, it was her.

She possessed a forthrightness made possible by her faith. I know so because that Sunday nine years ago her candor cut me to the quick. The law kills. And having laid down the law, Charlotte applied it in kind. She loved me. But— thank God—she loved Jesus more than me. Hence, she risked speaking the truth.

Charlotte was too polite and respectful to shame me in front of onlookers. Only after the crowd had petered out, did she approach me. She gave me a tight, fierce hug and a gentle kiss on my cheek. She patted her hands on the stole against my chest and then she put her hands on my elbows and bore holes in my eyes.

“Well, reverend, you certainly preached the gospel out of that sermon,” she said softly.

Confusion creased my brows, “Um, thank you.”

“It was not a compliment.”

They were just five words.

But they stung me.

“Tell me,” she said, “Maybe I was visiting my son in New Jersey and missed it. Exactly which Sunday during the previous administration did you preach that sermon? Certainly you must have preached a similar sermon because— as I’m sure you’re aware— that president started family separations and deported more people than this president.”

“I didn’t realize you were a supporter of…” I mumbled, sweat starting to bead on across my head.

“I’m not,” she corrected me, “I guess I’m an independent these days. But I’m definitely partisan when it comes Jesus. And today, whether or not what you said happened to be true or biblical, it sure sounded like you were using Jesus for your own project rather than pointing us to him and his work.”

In the Gospel of Luke, just after the devil tempts him in the wilderness for forty days, Jesus returns home to Nazareth to preach his first sermon. Jesus announces that the prophet Isaiah’s promise is fulfilled in him; the LORD’s covenant blessings will extend beyond his people Israel even to the ungodly Gentiles. Those in the synagogue respond by attempting to toss Jesus to his death.

If Jesus will not abet their worldview, they will not abide him.

In the Gospel of Matthew, just before he enters Jerusalem triumphant to a king’s welcome, the mother of the sons of Zebedee sees in Jesus’ impending reign an opportunity for her boys and so for herself. She braces Jesus with a request, “Say that in your Kingdom these two sons of mine may sit one on your right and one on your left.”

She sees in Jesus only what he can do for them.

When Jesus gives the twelve disciples power and authority over the demons, those same two “sons of thunder,” James and John, see in such privilege only the opportunity to manipulate the power of Jesus to settle an old grudge between the kingdoms of the North and South. “Lord,” they ask Jesus, “May we command fire to descend from heaven and to destroy them?”

They find in Jesus a tool for the preexisting partisan acrimony.

After Jesus’ temple tantrum, Judas’ betrayal is not outright treachery so much as an attempt to fit Jesus to Judas’ own agenda, forcing Jesus to act violently against the unjust temple system.

Rather than being with Jesus to the end, Judas attempts to manipulate Jesus to his own preconceived ends.

Even Pontius Pilate initially refuses to condemn Jesus. Pilate resists Christ’s condemnation not because Pilate is a righteous man but because Caiaphas seeks to extract such a sentence from Pilate. And Pilate insists on reminding the chief priest who the boss is in Jerusalem.

Caiphas and Pilate simply view Jesus as a pawn in their power struggle.

Even Peter! At the Transfiguration, on Holy Thursday, and just after the LORD calls him to follow, Peter does not want a crucified messiah. Peter wants only a Christ who conforms to his expectations.

Like Jonah attempting to flee from the God who dispatches him to hated Nineveh, in the end every last person in the gospels attempts to turn Jesus to their own ends. In spite of the fact Jesus is never for a moment in their power. In the Gospel of John, Jesus does not pray in Gethsemane for the cup to pass him. Jesus instead asks in the garden, “What shall I say? “Father save me from this hour”? No, for this purpose I have come to this hour.”

Though he appears to be a victim, beaten and spat upon and led to his execution, in reality Jesus is turning— through his voluntary self-offering— the destruction of his body the temple into the act of raising it up.And Mary alone is his accomplice.In the end every last person in the gospels attempts to turn Jesus to their own ends. Everybody but his Mother.That is, Mary assents to and cooperates with the End elected by the Son. Mary does not say “No” to God’s “No” to sinful humanity. The Son suffers at the command of his own divine will and none other, but his Mother does not resist. She does not say “No” to the cross.

On Good Friday, Mary does not shout, “Do NOT crucify him!”

Mary never pleads, “Do not crucify him!”

For the first time in her vocation, Mary does not speak. It is as if her silence, like Simon of Cyrene, helps her son to carry his cross. In fact, neither mother nor child utter any words along the Via Dolorosa, as though the pain and the urgency and the effort of the Road of Sorrows is their shared labor.

Just as Jesus contains in himself the coincidence of opposites, so too is the work of salvation both human and divine, the mutual labor of the Son with his Mother.

Elizaveta Pilenko was born in 1891 along the Black Sea in the Russian Empire. Her parents were devout Christians and raised their daughter such that, as a child, she emptied out her piggy-bank to contribute to the painting of an icon of the Mother of God for her family’s church. When she was a teenager, Elizaveta’s father died unexpectedly, a tragedy which twisted her faith into atheism. In 1910, Elizaveta married a Bolshevik activist who introduced her to a community of artists and poets and writers. To her surprise, among their many discussion topics, the group often talked theology.

Miraculously, her faith returned.

As godless communism consumed her country, Elizaveta secretly wore lead weights sewn into a hidden belt as a way of reminding herself "that Christ exists.” She joined an Orthodox Christian group, the Russian Student Christian Movement in 1923 and soon began to write on theology and the lives of the saints. A refugee in Paris, in 1932 the theologian Father Sergei Bulgakov consecrated Elizaveta as a nun in the Russian Orthodox Church. In taking her monastic vows, she chose for herself the name of the LORD’s Mother.

Mother Maria of Paris refused to flee to safety for America when the Germans invaded France in 1939. "If the Germans take Paris, I shall stay here with my orphans and old women,” she replied to entreaties, “The end is not mine to choose; I must follow Christ wherever he leads me.” A year later, in addition to smuggling children out of the country in trash cans, Mother Maria of Paris conspired with her priest-in-charge to provide certificates of baptism for Russian Jews hoping to avoid the camps. Nazis arrested her a year later and sent her to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Only a month before the camp was liberated, she was executed when she insisted the guards take her life in place of a Jewish child.

Deaf to the pleas for common sense, Mother Maria responded, “It is not for me to turn the LORD Jesus to my preferred end. This path is none other than his labor to which he enjoins us to share.”

Before she was martyred, Mother Maria authored an essay on her namesake, in which she wrote:

“The cross of the Son of Man, voluntarily accepted, becomes the doubled-edged sword transfixing the soul of his Mother, not only because she voluntarily choose it, but because she cannot not suffer the sufferings of her son... He undergoes the voluntary sufferings on the cross, she co-suffers with him. She co-participates. She co-feels, co-suffers. She is co- crucified… The whole mystery of Mary is in this co-uniting with the work of her son…”

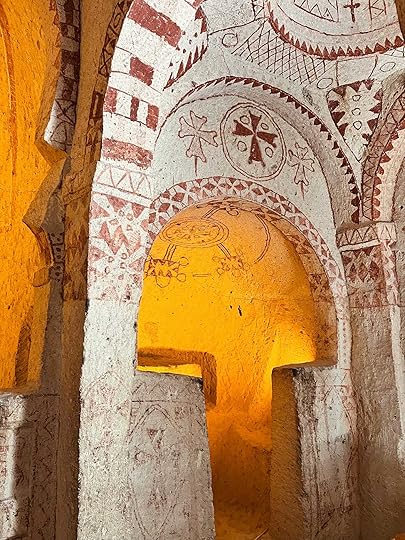

I recently spent ten days in Asia Minor, following in the footsteps of Paul’s missionary journey, exploring the apostolic churches of the New Testament, and visiting the Byzantine basilicas where the ancient church fathers formulated the ecumenical creeds which govern us today. Across all those sites, which span centuries, I saw shockingly few crosses and zero depictions of the crucifixion. There were many icons of the Triune God at table with Abraham and Sarah. There were abundant images of Mary with child, and there were still others of Christ the Cosmic Judge. There were even several Anastasis icons, images of the Risen Christ yanking the dead by their forearms up through doors of Hades.

But there were no icons of the crucifixion of the LORD.And the reason is simple.For the first millennia of the faith, the Passion was the climax of Christ’s labor but it was not itself the central redemptive event.For the ancient fathers and the first Christians the Son’s saving work was not his suffering and death but his faithful and obedient life lived unto death— even death upon a cross. This is nothing other than what the apostle Paul writes to the Colossians— that when the Father delivers the crucified Son from the tomb, as though from a womb, Christ becomes the firstborn of a new creation. Or as Maximus the Confessor puts it, the Resurrection is a new Big Bang; at Easter God inaugurates a second cosmos, a new origin of creation, in Jesus Christ.

Thus resurrection happens not simply to the crucified Jesus but to the whole timeline of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. This entire life, from Bethlehem to Calvary and every moment in between, is what God vindicates by raising it up from the grave.

Jesus saves.

Not the cross.

As the Epistle to the Ephesians announces, Christ’s faithful life, an obedience that did not yield in the face of death, is what recapitulates— re-sources— all things in himself, overcoming sin and thereby healing our afflicted nature. Maximus echoes Ephesians when he writes, “Jesus is neither mere man nor naked God, for the preeminent lover of humanity has become— unlike us— a truly human creature; so that, human creatures may now become portions of God.”

He does not mean merely to absolve us.

He means to make us equals.

And if his faithful life is the means by which he does so, then Mary’s work of delivering him to the world does not end at his nativity but continues until the moment he gives up his Spirit. Mary’s labor pains do not cease on Christmas Eve but they stretch forth across his lifetime, all the way up through noon and three on a Friday afternoon.

Jesus saves not the cross.It is his faithful, obedient life even unto death that heals our nature.And therefore—His Mother shares his work by refusing to shout, “Do not crucify him!”“I’m definitely partisan when it comes Jesus. And today…it sure sounded like you were using Jesus for your own project.”

I was standing in the narthex, my shame revealing itself in beads of sweat erupting across my forehead.

When Charlotte released her hands from my elbows, I confessed.

“You’re right,” I said, “I’m so embarrassed. I don’t know how I could be so blind. I don’t know how I could’ve done that.”

She shushed me.

She embraced me.

And she whispered into my ear.

“We all try to bend God so he suits us. Fortunately, like Mary with Jesus, God does not save us without us. If I hadn’t said anything to you, Jason, I’m certain God would’ve sent someone to set you straight.”

“Amen,” I whispered back.

Like everybody but his Mother, we are adept at twisting Jesus to our own ends. We make him a mere Absolver of sins. We turn him into a Teacher of wisdom. We shrink him to a Stalwart for social justice. We make him the object of spirituality, the face of nationalism, the promise of prosperity, the payment for trespasses, the transaction necessary for salvation.

But the LORD Jesus wants to make us equals, members of himself, portions of God.

He aims at nothing less than to be at-one with you.

All in all of you.

Just so—

He insists on getting in you.

Quite simply if surprisingly, Jesus dies upon the cross— and his Mother lets him— so that he might become our food and drink.

So come to the table.

Taste and see.

Eat and drink.

Feed on him by faith.

Like Mary at his cross, the labor is mutual.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 29, 2025

Blood, Sacrifice, and Redemption

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Show NotesSummary

This conversation delves into the themes presented in Fleming Rutledge's work on the crucifixion, exploring the significance of blood and sacrifice, the nature of forgiveness, and the implications of God's love and justice. The discussion highlights the metaphorical understanding of blood in scripture, the finality of Christ's sacrifice, and the radical message of Hebrews, emphasizing that true forgiveness comes at a cost and that Jesus' sacrifice is sufficient for redemption. In this conversation, Josh and Tony explore the multifaceted nature of sacrifice, particularly in the context of love, culture, and spirituality. They discuss how sacrifice is perceived in contemporary society, the implications of self-sacrifice, and its significance in the life of Christ. The dialogue emphasizes the transformative power of sacrifice in personal relationships, parenting, and community, while also addressing the challenges and critiques surrounding the concept in modern culture.

Takeaways

The chapter covers a breadth of theological and contemporary themes.

Blood sacrifice is often misunderstood in modern contexts.

Forgiveness is costly and cannot be trivialized.

God's love is revealed through the suffering of Christ.

The concept of sacrifice is central to understanding the gospel.

The distinction between propitiation and expiation is crucial.

Christ's sacrifice is once and for all, not repeated.

The message of Hebrews emphasizes the finality of Christ's work.

Living in light of sacrifice means embracing forgiveness and mercy.

Understanding sacrifice informs our relationships and interactions. John's gospel emphasizes the ultimate sacrifice of love.

Cultural narratives often glorify certain sacrifices while dismissing others.

Parenting and teaching are inherently sacrificial vocations.

Self-care is important, but a life without sacrifice is impoverished.

Sacrifice connects us to the greater narrative of love and redemption.

The unpopularity of self-sacrifice reflects a cultural shift.

Sacrifice can be an act of strength, not weakness.

Christ's life and death embody the essence of sacrifice.

Extravagance in love and sacrifice is a reflection of God's nature.

Everyday acts of sacrifice contribute to a more compassionate society.

Sound Bites

"Sacrifice costs something of value."

"This forgiveness is costly, if it's real."

"The movement of the gospel is God coming down."

"God is not divided against himself."

"Forgiveness is not cheap."

"Trusting that it's enough."

"Greater love has no man than this."

"We don't need to kill."

"Being a parent is sacrificial."

"Christ is over all these pages."

"We serve an extravagant God."

"What would life be without sacrifice?"

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 28, 2025

The Incongruity of Such an Oblation

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

If the cross is so counter-intuitive and its meaning can only be grasped by faith, then how does the Church convert people to the message of Christ crucified?

Inside the 16th St Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama hangs a stained glass window featuring an arresting depiction of a brown-skinned Christ crucified upon the cross. I say arresting because the image leads the eye in two seemingly dissonant directions. In one direction, Christ’s body appears almost in motion as if he were not truly bound by his captors’ nails. In the other, his anguished visage recalls the Eastern icon called the Utmost Humiliation.

The window was commissioned by the people of Wales in response to the KKK bombing of the church in 1963, which murdered four little black girls. The artist, John Petts, expressed his intent that one arm of the crucified Christ appear turned against the demonic powers of the world while the other arm extends out, ready to embrace all of creation.

Accompanying the image is an inscription from Jesus’ parable of the Last Judgment, which I’d argue has grown rote and impotent by its almost exclusive use to admonish Christians to care for the needybut here gets deployed with convicting power: ‘Whenever you’ve done it to one of the least of these, You Did It to Me.’

Like I said, arresting.

More than that, Petts’ art offers a thick, visual summary of the argument Fleming Rutledge mounts in her latest book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, for the Wales Window brings to the fore her emphasis on real, flesh and blood history as the arena in which God in Christ acted upon the cross and in which God through the word of the cross acts still today. Where so much debate today on the atonement veers between the individualistic and the esoteric, Rutledge relentlessly fixes her study of the cross within the challenges and questions raised by a suffering, sinful world. In addition to lived history, the Wales Window highlights several other distinct themes that resonant through The Crucifixion:

Sin not as vices requiring sentimental, pious conversion but as Sin, Powers and Principalities that systemically enslave humanity, requiring liberation. The former is, really, a work of human piety while the latter is an invasion only God can work.

The need for God alone to work justice and to remake the world God created by rectifying the world that humanity, in bondage to Sin, has created.

The sufficiency of Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice upon the cross.

The irreligious, counter-cultural imperative of the New Testament that Christ’s death was offered not only in solidarity with the world’s forsaken and oppressed but ‘for’ the forsakers and oppressors as well.

March 27, 2025

Easter is Not Optimism

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

For this month’s module of the Iowa Preachers Project cohort, Chris E.W. Green joined to reflect upon his theology of preaching and how to preach the scriptures assigned by the lectionary for Easter Sunday.

Summary

In this conversation, Chris Green shares his journey from a Pentecostal upbringing to becoming a Bishop, emphasizing the importance of a robust theology of preaching and resurrection. He discusses the sacramental nature of preaching, the need for deeper understandings of resurrection beyond mere resuscitation, and the challenges of preaching Easter in a context where congregants may not fully engage with the liturgical calendar. Green advocates for a theology that acknowledges both the darkness of Good Friday and the hope of Easter, encouraging preachers to connect their messages to the lived experiences of their congregations.

Takeaways

Preaching is a sacrament that addresses the congregation.

Resurrection is not merely coming back to life; it is transformative.

Easter hope signifies the ultimate restoration of all things.

Theology of resurrection should shape our preaching imagination.

Good Friday and Easter are interconnected aspects of one revelation.

Preaching should resonate with the lived experiences of the congregation.

Context matters in how we deliver messages about resurrection.

The cross is glorification, not just suffering.

Every sermon should be unique to the moment and context.

We must engage with the darkness and light in our lives.

Sound Bites

"Preaching is a sacrament."

"Resurrection is not resuscitation."

"Easter is not about optimism."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 26, 2025

Thinking with Luther in the Land of the Fathers

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Exploring the pilgrimage places of the church’s Byzantine birthplace, I appreciate anew the way in which the encounter between the Christian gospel and Greek Hellenism necessitated that the church fathers proclaim the Triune Name in a manner intelligible to those shaped by the religion of Plato.

March 25, 2025

Just This Offering

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Our online study of Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ continued last night in my absence. I have had her book at the front of my mind as I travel through Turkey on pilgrimage. From the Hagia Sophia to the carved-out churches of Cappadocia— places lavished with iconography— I cannot help but notice a dearth of the image many Christians take to be central to the witness of the faith, the cross.

The disconnect between an absence of the crucifixion in ancient iconography and its preponderance in popular contemporary piety raises a question I first stumbled upon several years ago during an Ash Wednesday service.

Preaching on Psalm 51 several Lents ago, I noticed something as I followed along with the lector from the pew Bible open on my lap. David’s bracing, vulnerable confession of sin in the psalm concludes with this startling moment of recognition:

“…for you [God] have no delight in sacrifice; if I were to give you a burnt offering, you would not be pleased. The sacrifice acceptable to God is only a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.”

Surely this is a stunning epiphany to anyone who knows the Old Testament. In Israel’s scriptures sacrifices are frequent, systematized, and not only a delight to the LORD but prescribed by God himself to Moses from atop Mt. Sinai. Consider even the remarkable dissonance— what I discovered on Ash Wednesday only because my pew Bible was opened, flat on my lap— of David’s confession of sin with the psalm that immediately precedes it in the Bible’s prayerbook.

‘Those who bring their thanksgiving sacrifice [as commanded in Leviticus] honor me,” the LORD declares.

In Psalm 50.

Israel’s prophets, who come after David, voicing God’s judgment upon the greed and false piety of David’s heirs, introduce an even more virulent strain into the Bible’s thinking about the necessity and merit of sacrifice. The Christian Old Testament closes with the prophet Malachi heaping scorn upon sacrifices offered in vain, and the angry prophet of the rural poor, Amos, most famously announces God’s wrath thusly:

“…you that turn justice to wormwood, and bring righteousness to the ground!

…the Lord is his name, who makes destruction flash out against the strong, so that destruction comes upon the fortress.

For I know how many are your transgressions, and how great are your sins—you who afflict the righteous, who take a bribe, and push aside the needy in the gate. Therefore the prudent will keep silent in such a time; for it is an evil time. Alas for you who desire the day of the Lord!

Why do you want the day of the Lord? It is darkness, not light; as if someone fled from a lion, and was met by a bear; or went into the house and rested a hand against the wall, and was bitten by a snake.

Is not the day of the Lord darkness, not light, and gloom with no brightness in it?

I hate, I despise your festivals, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt-offerings and grain-offerings, I will not accept them; and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs. I will not listen to the melody of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

We recognize those last lines abut justice thanks Dr. King’s sermon on the National Mall, yet excised from their original context, they lose their punch. And (I suspect for white Christians) the connection to King turns Amos from a prophet of judgment into a dispenser of vague liberal hope in the triumph of the human spirit.

The canon’s juxtaposition of Psalm 50 with Psalm 51 is not an outlier.For anyone with ears to hear, there is precisely this unresolved tension running throughout the Old Testament as to whether sacrifice is something that God in any way desires or requires. What do Christians make of this ambivalence regarding sacrifice when we consider what we take to be the ultimate sacrifice, Christ’s expiatory offering of suffering and death upon the cross? Is God’s self-giving in the Son with their Spirit pleasing to the Father, as the poet of Psalm 50 might imagine? Or is the murder of an innocent scapegoat upon a cross but another example of what Amos decries as the status quo’s practice of turning justice into wormwood? Worse, would God look upon us, who turn such an injustice as the crucifixion into a pleasing, even necessary sacrifice, and thunder “I hate, I despise, your worship?”

What do Christians make of this ambivalence regarding sacrifice when we consider what we consider the ultimate sacrifice, Christ’s expiatory offering of suffering and death upon the cross?

Fleming Rutledge’s book The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ has become a guide to which I turn every season of Lent. Rereading it recently, I recalled observations offered by the novelist Marilynne Robinson, whose keen theological mind nearly matches her peerless prose. In an essay entitled “Metaphysics,” from her book the Givenness of Things, Robinson writes:

“I know the Bible interprets Christ’s passion as expiatory, the world’s suffering as the consequence of sin, for which Christ is a guilt offering. I note as well that when God speaks through the prophets about sacrifice he treats it as the expression of a human need he tolerates rather than as anything he desires.

Certainly the death of Christ has been understood as expiation for human sin through the whole length of church history, and I defer with all possible sincerity to the central tenets of the Christian tradition, but as for myself, I confess that I struggle to understand the phenomenon of ritual sacrifice, and the Crucifixion when explicated in its terms. The concept is so central to the tradition that I have no desire to take issue with it, and so difficult for me that I leave it for others to interpret. If it answered to a deep human need at other times, and it answers now to other spirits than mine, then it is a great kindness of God toward them, and a great proof of God’s attentive grace toward his creatures.

I do not by any means doubt the gravity of human sin or question our radical indebtedness to God. I suppose it is my high Christology, my Trinitarianism, that makes me falter at the idea God could be in any sense repaid or satisfied by the death of his incarnate self.”

As we progress through Lent and Pascha looms ever nearer, I wonder:

Is our thinking that Christ’s cross is a necessary sacrifice for sin a kindness God permits?

Is it a kindness the LORD allows because, though God hates all devotion devoid of any concern for justice, it’s just this offering, needful or not, that every Good Friday, between noon and three, delivers what God most truly desires—a broken and contrite heart?

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers