Jason Micheli's Blog, page 16

March 10, 2025

The Crucifixion Study

Hi friends… Just a reminder we will begin our Lenten study in 30 minutes, discussing Fleming Rutledge’s book and specifically the motif of Passover and exodus.

You can find the studio here: https://riverside.fm/studio/s-studio-...

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Jesus Outfoxed the Fox

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

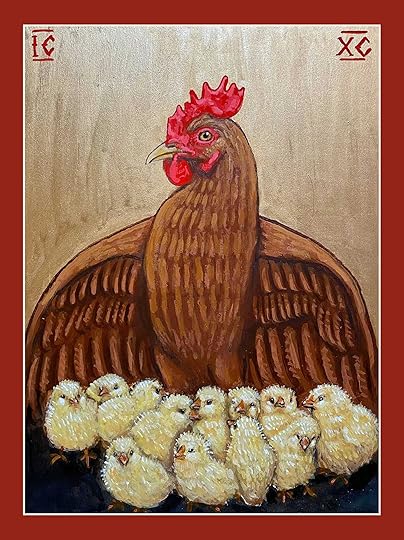

The lectionary Gospel passage for the Second Sunday of Lent is Luke 13:31-35:

“At that very hour some Pharisees came and said to him, "Get away from here, for Herod wants to kill you." He said to them, "Go and tell that fox for me, 'Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work. Yet today, tomorrow, and the next day I must be on my way, because it is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem.' Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! See, your house is left to you. And I tell you, you will not see me until the time comes when you say, 'Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord.'"

It’s important to read the animal imagery in nesting-doll sequence in order to see in it Christ’s work of undoing death.

March 9, 2025

He Makes a Creature Capable of Making Him

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Lent 1 — Luke 2.22-35

Neither Martin Luther nor John Calvin would concur with the way their Protestant posterity have diminished Mary to a character in a creche. For Lent, therefore, I will be preaching on the Seven Sorrows of Mary, journeying to the cross with the first disciple to follow him there.

I have a secret to spill.

Until now I have not shared it with anyone, save my friend who edits my sermons every Saturday evening.

Approximately fifteen years into my vocation as a preacher, my paternal grandfather passed. A child of the Great Depression, my grandfather grew up poor in a crowded house with too many mouths to feed. After World War II he parlayed the GI Bill into an engineering degree from Drexel University. He built naval ships in Norfolk, Virginia and later became a savvy player on the stock market, amassing a modest fortune and purchasing a mammoth cattle ranch in Broken Bow, Nebraska. When my grandmother entered a nursing home, he began attending worship services several times a week at a nearby Lutheran church. Despite his personal devotion, he expressed something more than chagrin that I had elected to answer Christ’s call upon my life.

Once we had buried him, the family gathered at his place to receive the specific items he had designated in his will for his children, step-children, and grandchildren. We stood in a circle and waited as his widow read a name and distributed an item. I did not receive his favorite straw Stetson, as my cousin did. I did not get the antique Colt revolver another received. Instead she handed me a fat, sealed envelope containing five folded pages. In his small, block engineer’s drafting script, he had written me a single-spaced, double-sided letter— ten pages in all— excoriating me for “wasting my potential and wasting his money on such a trifling pursuit.” After all, he had helped pay for my college education. He felt both betrayed and disgraced by the fact I had not pursued “a more profitable and enriching career.”

“You’ve wasted your life on Jesus, but perhaps it’s still not too late to do something worthwhile with your life.”

Those were his last words to me.

I remember standing in front of the fire place in that circle of family members, stuffing the letter back in to its envelope, slipping the envelope back in to my breast pocket, and desperately trying to keep my face from betraying the shame I felt.

The sorrow.

Standing there, to my surprise— to my disquiet even, I did not think upon Jesus but his Mother. Or more accurately, she just came to me. In the same unsettling and mysterious way that Jesus once appeared to me as a teenager at an ordinary suburban church and pulled me, against my will, into faith— in that same mystical manner— Mary was just there. It was not a vision per se but an ineffable presence. I do not know how I knew it was her; I only know that I knew it was her.

Here is another secret.

It is not the only time she has happened to me.

My friend and former classmate Matthew Milliner is a professor of art history at Wheaton College. Though he is an Anglican— a Protestant— his specialty is Marian iconography. Both in public lectures and in private conversation, Matt has remarked to me how resilient images of Mary the Mother of Jesus have been throughout history. “She keeps showing up where she’s supposed be absent,” he said to me not long ago. Despite the later Reformation’s periods of stark iconoclasm, images of Mary stubbornly abided in the Protestant Church.

“There’s something about Mary that meets believers in their need,” Matt told me recently, “She has persisted as essential to the church’s faith even in those parts of the church that have sought to evict her from her prominence in the work of salvation.”

When Jesus dispatches the twelve to preach the Kingdom of God to the lost sheep of the house of Israel, he adds a disclaimer for the disciples:

It sounds like a harsh word of prophecy.Until you realize Jesus is merely stating reality.“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law (a grandfather against his grandson).”

I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.

Jesus is speaking retrospectively not prospectively. He is not alluding to the effect he will have on the world. He is acknowledging the impact he has already had on it, beginning with and in his own family, if not before then certainly from the time he was but forty days old.

Over the millennia, the church’s dogma and piety have heaped a plethora of honorifics upon Mary. However, foremost and first among her titles are two. One is an item of the church’s creedal confession; another is displayed by the church’s scriptures.

First, Mary is the Theotokos, the Mother of God.

Such a designation for Mary was inevitable once the Nicene Creed confessed in 325AD that her boy is truly God, “of one substance with the Father.” Just so, a century later the ecumenical Council of Ephesus stipulated Mary as Theotokos to be an essential article of orthodoxy, departure from which made one no longer a Christian.

Second, according to the scriptures Mary is the Mother of all of you.

That is, Mary is the Mother Believers. When Mary assents to the angel Gabriel, saying, “Behold I am a slave of the LORD; let it be with me according to your word;” when she assents to the annunciation, she becomes the first disciple. Thus the Mother maps for us the way to follow the Son in obedience. As the one who carries within her the Word of God, Mary is the prophet among prophets, the final and ultimate prophet, writes the church father Maximus the Confessor. And remember, no prophet is finally welcome among her own people; therefore, the Mother of Believers is simultaneously the Mother of Sorrows.

St. Luke begins stitching the thread of this plot in the opening chapters of his Gospel.

When Mary’s boy is between four and five weeks old, she brings him to the temple in Jerusalem for two rites prescribed by the law. Having given birth, Mary required ritual purification. That’s the purpose behind the price of the two turtledoves.

The second rite prescribed by the covenant is the law requiring the consecration of a mother’s firstborn son to the LORD. Over time however, the role designated for the firstborn son was assumed instead by the tribe of Levi. This is why the Book of Numbers provides a means by which a mother might buy back her firstborn son from the LORD. In Numbers 18 the LORD says, “The firstborn son you shall redeem…And his redemption price you shall fix at five shekels in silver”

Notice: Luke assumes you will catch what is missing.Mary does indeed offer the two birds necessary for her purification. But when she brings Jesus to the temple to present him the LORD, she does not supply the five shekels. No priest receives the offering from her. She does not pay the redemption price.

She does not buy Jesus back from the LORD.Simeon prophesies that a sword will pierce Mary’s heart.

But don’t you see— her heart already has been pierced!

Mary has offered Jesus as a living sacrifice, relinquishing her firstborn boy. In not redeeming Jesus, Mary she renounces any claim at all to his life.

As the Protestant biblical scholar William Glass writes:

“Although Mary receives a gift infinitely more valuable than what had been given to Hannah, she renounces the gift even more completely. Mary, in bringing her son to the temple, gives him wholly over to God. Though Jesus will live to God, he will be as dead to her. Mary renounces all benefits that her child was to bring her. Given the nature of the benefits, she makes an offering to God that no one could make who loved anything in the least respect more than God.”

Mary does not buy back Jesus from the LORD. It is no a trivial detail that in the very next scene Luke narrates Jesus is twelve years old. Mary and Joseph lose him in the crowd and commotion of the passover pilgrimage. Mary eventually discovers Jesus in the temple only to find her mother’s relief met with a blunt reminder of the redemption price she did not pay, “Why were you looking for me? Did you not know that I must be in my Father's house?”

There is no way for Mary to be the Mother of Believers but for Mary to be also the Mother of Sorrows.Nine years before my grandfather died, she also happened to me.

My wife and I started the adoption process for the first time. After the initial medical tests and financial disclosures and background checks, we had to complete a form delineating precisely which maladies, diseases, and handicaps we were prepared to accept in a child. The form was longer than that letter my grandfather had left me. It was harrowing to reckon so with the reality that you can neither control your child’s future nor protect them from the contingencies of life.

Based on our responses, our social worker eventually contacted us to inquire if we would consider adopting an infant boy in Guatemala who had been born with a severe cleft palate. “Lucas will need considerable surgery,” she said to us, “And he may not survive the interim.”

He did not.

We said yes to him. And legally, on paper at least, he was ours. But he was nevertheless out of our hands. And he died before we ever met him. It was— is— a strange grief. A few days after we received the news, I was five miles into a run along the Potomac when anguish completely arrested me. I was standing on the side of the bike path and crying and in way attempting piety when she was just there to me. Not as a character in a history I believe to be true. Not as a comforting thought— it wasn’t comforting at all, exactly. She was there, a presence as real as the shoes on my feet. I do not know how I knew it was her; I only know that I knew it was her.

And when it was gone— when she was gone, I did not feel less sad.

But I no longer felt alone.

“There’s something about Mary that meets believers in their need,” my friend Matt said to me.

Of course there is!

Jesus alone carries the cross. But Mary alone carries the sword. He bears our sins. She bears our sorrows.And her grief is heavier than his tree because it shares all of our sorrows.

Ten years ago during my first bout with cancer, I was sitting in the infusion lab linked to a bag of poison. The book in my lap must have given away my gig, for the woman sitting across from me wagered I was someone she could trust with weird things.

“Are you a Christian? Or a priest? ” She asked me, nodding at my book.

“A little of both,” I replied.

“Can I ask you something?”

“Sure,” I looked around the infusion lab,”It’s not like I’ve got a lot of other options at the moment.”

She started with a story.

And tears.

She was being treated for a cancer that had ended her pregnancy.

“A week or so after it happened…” and her voice trailed off as she tried to maintain her composure, “Mary appeared to me and consoled me. It was like a waking dream but it was real.”

She looked at the ceiling and sighed, “I’m not even Catholic.”

And then she looked back at me, “Does that sound crazy? Is it even possible?”

“Of course it’s possible,” I answered, “I talk to my grandpa just about every day and he died a few years ago.”

“That’s different,” she said.

“No, it isn’t. When we call the church the Body of Christ, we mean that Jesus does not wish to be known apart from his saints— living and dead. And chief among them is his Mother. Wherever Christ is, the saints are.”

“But…” she was working out the logic, “isn’t there the danger she’ll take the place of Jesus?”

“No,” I replied, “She doesn’t take the place of Jesus. She’s the place God makes for Jesus— still. It’s important that we call her Saint Mary. Wherever she is, he is.”

“But why would she come to me? Why not him?”

I said:

“It’s like the Bible says, Christ’s Body is made up of all kinds of parts and members. I reckon there are some sufferings Jesus thinks are best handled by his Mother.”Mary doesn’t take the place of Jesus; she’s the place God makes for Jesus.

It is a grave error— and certainly not one Luther intended— we attend to Mary only around Advent. Such a myopic focus omits the most remarkable aspect of her calling. Against all natural inclinations— for the sake of redemption— Mary never redeems Jesus. She never pays the five shekels to buy him back from the LORD.

As William Glass writes:

“Like the mother of Moses, At the temple, Mary receives Jesus back for a time, but always under the aspect of one who is no longer hers.”Just after Jesus calls twelve disciples to follow him, his mother and brothers call to him. The crowd informs Jesus, “You mother and your brothers are outside, seeking you.”

And Jesus replies, “Who are my mother and my brothers?” Looking at the crowd instead of Mary, Jesus says, “Here are my mother and my brothers.”

When his teaching elicits anger in Nazareth, those in the synagogue react with a sneer, throwing what they take to be the scandalous nature of birth back in his face, “Is this not the son of Mary?”

They do not say, “The son of Mary and Joseph.”

In Cana, when Mary tells Jesus the wine has run dry, he responds not unlike he had as a boy in the temple, “Woman, what concern is that to me?”

He doesn’t call her mother.

These episodes are not scandals however; they are sorrows. They constitute the living sacrifice she consented to offer.FOR YOUR SAKE!She gives Jesus over to God; so that, the Father can gift him to the world. This is why she disappears and returns in the Gospels, as one only adjacent to her child. Finally at the cross Mary repeats the relinquishment she had offered in the temple. On Good Friday, Mary does what Eve did not do and, so doing, she reverses the curse.

As William Glass writes:

“Whereas Eve plucked the forbidden fruit from the tree, Mary waives her wholly legitimate right to the fruit of her womb, even when the rebellious crowd puts it on the tree of the curse. She refuses to take it down. Her fullness of grace, whatever it might mean, cannot mean less than her unfailing love for God and neighbor, the love that opens her hand and elicits from it the gift of everything of value that she has.”

Mary does not do what Mary Magdalene attempts to do at the empty tomb.

Mary does not cling to Jesus.

As Mother Maria of Paris, who was martyred by the Nazis, puts it, “Mary is the creaturely echo of the Father’s generosity.”

Last Friday, I lamented to my oncologist all the agony I had experienced in the preceding days. And I told him that more so than the physical pain I hadn’t been able to shake all week, I felt sorrow that I might not be able to do my job if this new normal will be permanent.

Sorrow— to suffer in the Spirit- is the right word.

My doctor adjusted my medications and then said to me, “You could always go on disability.”

I shook my head, “Got any other ideas?”

“Say a “Hail, Mary,”” he said.

He’s Greek Orthodox.

So I do not know whether he was joking.

He need not have been.

“I reckon there are some sufferings Jesus thinks are best handled by his Mother,” I said to the woman in the infusion lab.

I went back to reading my theology book. After a few minutes, she said to me, “I’ve been going to church my whole life. It never occurred to me until just now how we get to believe some really weird things.”

I smiled and nodded and went back to my book.

And then she reiterated, “I’m not even Catholic!”

“Neither am I,” I replied.

She shot me a look, confused.

There is no way for Mary to be the Mother of Believers but for Mary to be also the Mother of Sorrows. We know Mary’s sorrows. The Gospels make those plain. But exactly what does Mary believe? The angel’s annunciation is short on details. He does not divulge the particulars. He does not reveal the path ahead. He whispers a hint neither of the cross nor the empty tomb. Despite the Christmas song, she does not know.

She does not know because…

Gabriel does not tell Mary the plan.Gabriel only gives her a promise, “Nothing will be impossible with God.”It is the only such promise in the New Testament. As Fred Craddock says, it is the creed behind the creeds. Nothing will be impossible with God— that’s Mary’s only handhold. That’s all she knows. Knows by faith. Mary is the Mother of Believers because she is the first to trust the not-impossible power of the LORD. Mary is the Mother of Believers because she trusts that the not-impossible power of the LORD is yet greater than the sum of all her sorrows. She is the first disciple to follow Jesus to the End, clutching only the promise that nothing is impossible for God.

Like the messenger to Mary, I am in no position to unveil for you the LORD’s plan. And anyone who purports to know what God is up to, right now, in our world is a liar and a thief.

Nevertheless, Jesus has called me to hand over a promise.

Like Mary, a promise is all you get.

Not the particulars of the plan for your life— only a promise.

Therefore:

As sons and daughters of the Second Eve, hear the good news.

Whatever sorrows you ponder in your heart, no matter the swords that have pierced them, despite what you may be suffering in the Spirit, even if Jesus has proven a shard that’s cut divisions in your family or among your friends— one day all sad things will come untrue.

They will.

And if you ache over the state of the world, if you are disoriented by the chaos of these recent days, if you feel shamed and scared by “fork in the road” emails— one day all things will be rectified.

They will.

I know it can sound absurd. I know I cannot provide a plan that shows how we get from here to there. I wish I knew the plan for me! I only know the promise— I believe it: “Nothing will be impossible with God.”

Speaking of impossible possibilities, come to the table.

Because Jesus does not wish to be known apart from his saints, he may be the host but it is not wrong to say that Mary invites you to this table, that my grandpa invites you to this table, that any loved one whose loss is your sorrow invites you to this table.

There is a whole other half circle to this table we cannot see.

They’re all here.

Come to the table.

How loaf and cup can be him for us is but one of the weird things we get to trust.

(image from Chris EW Green)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 8, 2025

The Mystery of Christ

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is the final session of our study of Robert Capon’s The Mystery of Christ.

Next up, we will start with Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ. We will discuss her first motif, Passover and Exodus.

Summary

In this conversation, Todd Littleton and Tony Robinson explore the themes of peace, acceptance, and the role of the church in understanding these concepts through the lens of George's experience. They discuss the nature of peace in troubling times, the importance of accepting one's acceptance, and the implications of the mystery of Christ. The dialogue emphasizes the communal aspect of faith and the shared experiences that shape our understanding of peace. In this conversation, Todd Littleton and Tony Robinson explore the themes of grace, its transformative power, and the mystery of Christ in creation. They discuss the distinction between cheap grace and free grace, emphasizing that grace is a gift that cannot be earned. The dialogue also touches on the cosmic nature of new creation and the importance of imagination in faith, highlighting the need for a communal understanding of grace rather than an individualistic approach.

Takeaways

George's experience of peace was transformative and lasting.

The peace of Christ is not dependent on worldly circumstances.

Acceptance is a crucial aspect of experiencing peace.

The church plays a significant role in narrating the story of God.

Peace can be experienced even in the midst of turmoil.

The mystery of Christ is revealed in everyday life.

Grace is a constant presence in our lives.

Community enhances our understanding of acceptance and peace.

Moments of revelation can lead to profound changes in perspective.

The journey of faith is often about discovering what has always been present. Grace is universally available to everyone.

Cheap grace implies a merit-based approach to faith.

True grace is transformative and changes lives.

The mystery of Christ is present in all creation.

New creation is a cosmic reality beyond individual experience.

Imagination plays a crucial role in understanding faith.

The church should focus on communal expressions of grace.

Scrutinizing ourselves can detract from the joy of grace.

Grace is not a concept but a lived experience.

The emphasis on grace should not lead to individualism.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 7, 2025

Evil as Person

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Lent begins this Sunday with Luke’s account of Jesus’s temptation in the wilderness, a text which posits, to put it quite simply, that Satan and his demons have been given possession over the governments of the world. For the Prince of Lies to offer the Oval Office to Jesus implies it is already within his grasp to give to Jesus.

Just so, the scriptures show forth nothing more mysterious than our monstrous world.

Starting out as a rookie preacher, Karl Barth struggled with translating the ancient, premodern world of the Bible for contemporary listeners. As happens with many preachers, seminary had nearly wrung the faith out of Barth, rendering the Bible as a text to be demythologized rather than declared. However, when Barth discovered that all of his former professors had fallen under the Kaiser’s spell and signed an enthusiastic endorsement of Germany’s unprovoked war, Barth concluded the liberal theology they had handed over to him was rotten at the core. He immediately set upon the task of rebuilding his faith from the ground up.

Around the same time, while Barth was attending his brother’s wedding, he and a friend traveled a short distance to the town of Bad Boll in order to meet Christoph Blumhardt, a young pastor whose father, Johann Blumhardt, had, some years earlier, exorcised a demon from a young woman in his parish. The exorcism had sparked a revival in southern Germany.

The young woman’s name was Gottlieben Dittus.

She lived with her two sisters and brother in a ramshackle basement apartment. The was cheap because not only was the plaster peeling and the paint fading, the walls themselves knocked and creaked uncontrollably. Soon Gottlieben started hearing other noises, shuffling feet and scampering in between the walls. Next she began seeing things, shapes and light. One day she started speaking in voices not her own.

The sisters of Gottlieben Dittus reached out to the pastor for help. Pastor Blumhardt was every bit the modern man. So Blumhardt followed the science. He sought out doctors and treatments and medicines. Weeks went by as neighbors began complaining about the noise emerging from the sisters’s apartment. Gottlieben was now speaking in the voice of the deceased former owner of the house, who led Blumhardt to discover bones buried under the floorboards and bodies in the adjacent field. Despite his modern prejudices and secular superstitions, Johann Blumhardt eventually became convinced that what was holding the young woman hostage was, in fact, a minion of the one the prophet John sees falling as a star, a star who clutches the keys of hell.

One night, three months in to the ordeal, as Gottlieben fell into another demonic trance, Blumhardt took her hand and shouted into her ear:

“Place your hands together and pray, ‘Lord Jesus, help me!’ We have seen long enough what the devil can do; now we desire to see also what God can do.”

It was a moment like that one, only months later, that the demon finally left her. Gottliebin cried out in a strange voice, loud enough for the neighbors to hear, “Jesus is victor!” The demon left her— that little word felled him.

The Bible refuses to acknowledge that our “real” world deserves the adjective.Just as we cannot speak Christian by eliminating the word angel from our vocabulary neither can we preach the gospel without explicit reference to God’s opponent.

Christianity just is a struggle with a personified Liar.March 6, 2025

"Having a fat God and having a skinny God are two completely different things."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

A few items:

Thank you for your continued prayers and encouragement. My most recent sermon elicited much care and concern. As I navigate my way through chemo’s (unexpectedly arduous) side-effects, I truly appreciate your support.

Our Monday night live sessions will continue next week. For Lent, we will be kicking off a discussion of Fleming Rutledge’s big book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ. For your participation, we invite you to read the first “motif” chapter in her book on the Passover and the Exodus. You can find her book here. If circumstances prevent you from getting it, let me know. I’ve got about a dozen copies on hand. But do check it out! Fleming is a subscriber and lurker here, and she’ll know if you didn’t do your homework.

The video from the final session of the Mystery of Christ will be available later this week.

Finally, here is a sermon on the Transfiguration by my friend Ken Sundet Jones, preached at Grand View University’s chapel. And remember, if you’re a preacher, consider joining Ken and me for the next cohort of the Iowa Preachers Project. Applications will open at this Spring’s Mockingbird Conference.

Jesus‘s transfiguration, which we just heard about, is one of the few things, apart from the Lord‘s death and resurrection, that shows up in all four gospels. So it must be important. But it’s such a strange story: Jesus takes a few disciples with him and goes up on a mountain top. The disciples fall asleep, and when they wake up, they see Jesus standing with Moses and Elijah with what we might call a strange look on his face and shining clothes. Like I said, it’s a strange story. But let’s see if we can get at it from a different angle so that it makes more sense for us.

Today is Mardi Gras, which is a French word that we get via New Orleans, which was originally a French port before Thomas Jefferson bought it in the Louisiana purchase. And Mardi Gras is a church term. Mardi means Tuesday, and gras means fat. It’s called Fat Tuesday, because it’s the last day before the season of Lent, which in the Roman Catholic tradition is the somber church season in which believers are called on to think about their own sinfulness and need for Christ’s work on the cross.

One of the ways Christians have observed Lent is to take on some kind of discipline. In the Roman Catholic tradition and elsewhere, there are restrictions on diet that people often adhere to, including not having meat on Fridays. That’s why McDonald’s and Culver’s make a big deal about their fish sandwiches. They want fast food spending from Catholic customers. But that’s just the surface of things. The goal for the forty days of Lent is to join yourself to Jesus who went into the wilderness for forty days after he was baptized. During Lent you seek a more austere lifestyle and cut out things you don’t need, including, guess what? Fat. So, in this tradition today is the last day that you get to have two gorge on fat, including buttery pancakes, and syrup after chapel.

The odd thing about this tradition is that, in a way, it runs counter to the kind of God you have, the God, who is the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. If you want to know more about God during the season of Lent, maybe it’s not the best thing to do to go without, to starve yourself, or to become a mealy-minded person, feeling like you have to perform some obligation in order for God to regard you kindly. People often give things up for Lent, whether it’s fat or chocolate or Spotify or speeding or doom-scrolling on Facebook. Then they discover it’s harder to do than they expected, and they don’t follow through on their commitment, and they feel like less of a Christian, and then they worry about God‘s response. Such a slippery slope, and at its bottom stands a God who looks down on such failures, one who begrudges expending any mercy on his extremely fallible human creatures.

But the story of Jesus’s transfiguration on the mountain tells us something different. The transfiguration is all about something being revealed to the disciples. A veil that was draped between them in Jesus is lifted, so in Jesus’ strange look and glowing robes they see his glory, his bigness, his awesome, true nature. All his divine glory exudes from him like the rays of the sun. Psalm 23 says “my cup overflows” when it talks about what it’s like to be related to God. In this case, Jesus is a cup, overflowing with goodness and mercy — more goodness and mercy, actually than we human sinners can really stand. That’s why a cloud descends on the mountain, and Jesus becomes obscured. Just a glimpse of it had the disciples cowering. So it’s all hidden or clouded, so that we can access it in a way that doesn’t destroy us.

In fact, in about seven weeks, Christians will gather for Good Friday and hear about Jesus on another mountain, on Golgotha, where he hangs on a cross and breathes his last breath. This is not some different God from the overflowing ultimate goodness that streams from Jesus in the transfiguration. It’s the same thing, the same glory, but hidden behind its opposite. Jesus’s divinity revealed on the mountain of the transfiguration and on Golgotha when he’s crucified, both reveal the ultimate fatness of your God. In Jesus’ very being, in his living, breathing body and finally in his death on the cross, God intends to show you that you don’t have a skinny God; you have instead a fat God.

Having a fat God and having a skinny God are two completely different things.Having a skinny God is like being forced to eat All Bran and skim milk for breakfast, a handful of dry-roasted peanuts for lunch, and celery sticks for supper, and being told you should be grateful for it because it’s good for you. What kind of God is that? Is this the kind of God who would go to the bitter end of the cross to give himself to you?

But having a fat God is something altogether different. This is more on the order of being served a thick ribeye steak. And not just any steak, but one that’s marbled with fat. And as I’ve learned by watching episodes of America’s Test Kitchen, fat gives flavor. You want a fat God who has some oomph to him, a God you can save her, a God who’s more than merely nutritious or good for you. You want a God who, when you get a taste of him, you say to yourself “ I need another helping of that.”

Now I know all about fat. When I interviewed here at Grand View University 22 years ago, I weighed an eighth of a ton, 250 luscious pounds made all the more alluring by wearing bowties. The bowties, though, or camouflage. I hated being morbidly obese, as my doctor wrote in his chart, and dealing with things that came along with it like diabetes and for daily injections of insulin. So I went to Weight Watchers and lost 65 pounds. I gained back half, and in the last year have gotten back down to that low weight thanks to the Ozempic that, like Jesus himself, can do for me what I can’t do on my own.

So it’s good that I’m not as fat as I used to be. But you don’t want God who goes on a diet. You need a God who can fill you up so that you can say with the psalmist, “O taste and see that the Lord is good.” You need a God who grows bigger with every day. You need a God who’s as fat and overflowing as his eternal love and mercy.

In spite of Lenten disciplines and this whole business of giving something up for Lent, how about instead you take on something else? How about sinking yourself down into the Scriptures with the goal of seeing how fat God really is? How about showing up for worship on a Sunday morning so that this God, Jesus Christ himself, can provide you with a full banquet in the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper?

And if you are hungry for his word of mercy today, if you’re weary of the church’s demands to be more disciplined, if your mind about God is clouded, then you’ve come to the right place, because, as Jesus tells us, we do not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God. The mouth of God on the amount of transfiguration says, “This is my son, the beloved. Listen to him.” And what Jesus wants you to listen to, to hear and hear well, to savor, is that he is for you. The menu of grace he has put together is prepared for your taste buds, your belly, and your well-being. This is his word, his promise to you, that you can come to him and encounter the fattest of gods who will not turn away from you, but always give you more. Today and always. Happy Fat Tuesday! Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 5, 2025

The Last Flicker of Pride

March 4, 2025

What If Jesus HAD Made Bread from Stones?

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber!

With Ash Wednesday tomorrow, the other purple season sets upon us. The lectionary Gospel passage for the first Sunday of Lent is Luke 4.1-13:

Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tested by the devil. He ate nothing at all during those days, and when they were over, he was famished. The devil said to him, "If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become a loaf of bread."

Jesus answered him, "It is written, 'One does not live by bread alone.'"

Then the devil led him up and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world. And the devil said to him, "To you I will give all this authority and their glory, for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please. If you, then, will worship me, it will all be yours."

Jesus answered him, "It is written, 'Worship the Lord your God, and serve only him.'"

Then the devil led him to Jerusalem and placed him on the pinnacle of the temple, and said to him, "If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for it is written, 'He will command his angels concerning you, to protect you,' and 'On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone.'"

Jesus answered him, "It is said, 'Do not put the Lord your God to the test.'"

When the devil had finished every test, he departed from him until an opportune time.

You can listen to me discuss the passage for the first Sunday of Lent:

Luke reports that the Enemy’s first temptation targets Jesus’s hunger.

The question that Satan raises of the Son is as simple as it seldom asked:What would it have meant if Jesus had yielded?In Volume IV.1 of the Church Dogmatics, paragraph §59, Karl Barth reflects upon this very question under the header, “The Judge Judged in Our Place.”

First, Barth observes that none of the Synoptic accounts of the testing involve the Adversary asking Jesus to break the Law:

“In none of the three temptations is there brought before us a devil who is obviously godless or danger or even stupid. And in none of them is the temptation a temptation to which we might call a breaking or failure to keep the Law on the moral or juridical plane.

In all three we have to do “only” with the counsel, the suggestion, that He should not be true to the way on which He entered the Jordan, that of a great sinner repenting.He would have taken a direction which will not need to have the cross as its end and goal. But if Jesus had done this He would have done something far worse than any breaking of failure to keep the Law. He would have done that which is the essence of everything bad. For it would have meant that without His obedience the enmity of the world against God would have persisted, without His penitence the destruction of the cosmos could not have been arrested.”

Next, Barth reflects upon Jesus’s hunger strike and what it would have meant for Jesus to agree to Satan’s suggestion to turn stones into bread:

March 3, 2025

The Temptation was for the Tempter

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Once the Lord crushes the satan underfoot will Lucifer remain?

Lent begins this Sunday with Luke’s account of Christ’s trial in the wilderness.

The contemporary western church tends, in the case of the mainline, to psychologize the biblical character of Satan into oblivion. Evangelicals meanwhile appear to harbor such crippling anxiety about the specter of heresy they avoid entertaining the questions the church fathers felt freed by the gospel to ask. Among these questions, the question of the ultimate fate of Satan and the fallen spirits. The closure of the question, however, shuts down hopeful possibilities for reading the scriptures.

Positing the ultimate salvation even of Satan and his minions, the 20th century Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov reads the Gospels’s account of Christ’s temptation in the wilderness in light of the love of the Triune God. The temptations, Bulgakov ventures, were for tempter, who no longer believed the LORD is this faithful Son, his merciful Father, together in their Spirit.

March 2, 2025

Brute Facts, Buoyant Faith

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

I closed out our sermon series on the twenty-third psalm this morning. Blame it on the chemo brain, I misplaced the last half of my sermon manuscript. The text below therefore does not match up with the audio. Just in case anyone was bothered by the discrepancy! Apologies to Josh Retterer who labors as my editor gratis.

Transfiguration — Psalm 23

After I graduated from seminary, I worked as a chaplain in the Children’s Hospital at the University of Virginia. One night I was on call, attempting to catch some sleep by lying on top of a conference table in a dark office. It had been a busy shift. My hands reeked of sanitizer from visiting so many patient rooms. I was laying on the table, when my pager went off just after three o’clock in the morning.

It summoned me to a delivery room.

“The family is requesting a baptism,” is all the nurse managed to tell me.

The couple were from West Virginia. The husband— the Dad— was wearing a blue and yellow Mountaineers hoodie. A woman I intuited was his mother-in-law was sitting in the chair beside the bed, patting her daughter’s shoulder. She was wearing the pajamas she’d had on when she got a the call not much earlier than me. The mother was holding her swaddled, stillborn daughter in the crook of her arm, shushing her and smoothing her few fine hairs with her hand.

She turned her gaze from her daughter.

“We’d like you to baptize her, “ she said.

“Of course,” I mumbled nervously.

I fumbled about for a moment or two, finding a clean bed pan and a pitcher to fill with water. Slowly pouring it into the bed pan, I invoked the Holy Spirit so that the water might be a cleansing washing and a saving flood— a different sort of labor and delivery.

Then I took the tiny child and rested her in my arm.

I don’t remember their names, but after all these years I do remember hers.

I looked at her parents and asked, “What name is given this child?”

“Megan,” the girl’s mother spoke, “We want to name her Megan.”

And I looked down at her calm face, still splotchy from birth, and I said, “Megan, I baptize you in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

Three times I cupped my hand, scooped it up, and watched her tiny hair wave in the water. Then I handed her back to her mother, pulled out the little vial of oil I carried in my pocket, dabbed my thumb with it, and anointed her forehead with the sign of the cross.

“Megan, receive the Holy Spirit,” I pronounced.

And then Megan’s Mother looked up at me, “Preacher, can you read the Twenty-Third Psalm for us?”

Oblivious to the looming danger, I pulled my pocket Bible from my lab coat and turned to David’s prayer. The grandmother clutched my hand like she was standing at the end of a plank. I read.

All was good— until I got to the final verse, “And I will dwell in the house of the LORD my whole life long.”

Before I could get the amen out, Megan’s grandmother shot me a question, “What the hell was that?!”

“Um, it’s Psalm 23— like you wanted.”

“No it ain’t,” she replied, “We wanted to hear the dwelling in the house of the LORD forever one.”

“This is the New Revised Standard Version,” I replied limply.

And then she smacked me across my face, “How dare you take away their hope!”

I was about to apologize, save face, but she interrupted me, “God didn’t even let King David build that Temple in Jerusalem! Why in the hell would he be praying about the Temple? Don’t you know the scriptures?! I thought you were a preacher! Are you saying it doesn’t promise forever?!”

In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus leads three of his twelve up to the top of Mount Tabor wherewith, without preamble or announcement, the LORD unveils to them the true identify of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. “Jesus was transfigured before them,” Mark reports. Just as Christ’s crucified body is the lamp whose uncreated light cast shadows in the valley of death, Peter, James, and John see Jesus ablaze with the kabod YHWH— the glory of the LORD. In other words, there is one who is other from God but is simultaneously God— a second divine identity.

Thinking they have trespassed upon majesty, the disciples react in terror. Peter is so scared he cannot keep from speaking, offering to construct a House for the Lord atop the mountain.

Neither Jesus nor Moses and Elijah respond to Peter.

Instead God the Father answers.

The Cloud of Presence, which had accompanied Israel through the wilderness day-by-day for forty years, appears and covers their eyes from the glory too luminous to behold. The cloud that is God’s presence surrounds the disciples. Likewise, at the conclusion of his prayer, David finds that for all of his life, across the entirety of his experiences, he has been surrounded by God.

Admittedly, this is not obvious in the English.

As Old Testament scholar Richard Briggs gripes, the final verse of the twenty-third psalm is the most consistently mistranslated portion of David’s prayer. For starters, the verb of the first two subjects (“to follow”) is an especially weak translation of the Hebrew verb rādap, which means to pursue, to chase, to go after, or to hunt down. Follow makes it sound like goodness and mercy can barely keep up with you; quite the opposite, you are the object of their determined questing.

Moreover, the two subjects of the verb, goodness and mercy, are not generic nouns for prosperity and pardon. The first noun in Hebrew is ṭōb, as in, “The LORD commanded, “Let there be light,” and there was light. And God saw that the light was ṭōb.” Good— good for the covenant. The second noun in Hebrew is ḥesed. When the LORD renews his covenant with his people after the exodus, he appears in a pillar of cloud and pledges to Moses, “The LORD, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in ḥesed.”

Steadfast love.

Tov and Hesed.

These are not generic adjectives. They are covenantal nouns. They are attributes of God. And, as Thomas Aquinas notes, because there is no distinction between God’s attributes and God’s very self, when David takes his gaze off the path in front of him and looks over his shoulder, he professes that he is being pursued relentlessly by God. Which is a straightforward enough confession of faith except of course for the fact that the Shepherd is also simultaneously in front of him, leading him.

God is both bow and stern, fore and aft.

What Mark shows you on the Mount of Transfiguration is nothing more mysterious than what David invites you to pray in this psalm.

God the Shepherd is in front of David, guiding him.

And One who is other than God but is also identifiable with God is at one and the same time behind David, like a sheep dog, driving him to the Shepherd’s chosen destination.

In other words—

From tranquil waters to the valley of death’s shadow, from the presence of enemies to the persecution occasioned by his oily anointing; before him and behind him, all this time, all along, always— even on his worst day; even if he doesn’t realize it until he turns to look back— David has been surrounded by God. David has been both led and pursued by God— by the stubborn if inscrutable tov and hesed of the triune God.

Four weeks ago, I preached for the funeral of a friend. Sam was my favorite old guy in my former parish. A fellow aficionado of standup comedy, ten years ago Sam escorted me and my fifth grade son to a Lewis Black show at the Warner Theater. Lewis Black may be explicit in his vocabulary and hyper-partisan in his politics but he’s a relatively clean comedian. Thus, Sam said he felt comfortable bringing along a boy who probably should have stayed home and watched the Magic School Bus.

But for the show at the Warner Theater, Sam hadn’t factored the opening act into his expectations. I don’t recall the name of the comedian, but I know that he had a ukulele and that his first bit was a song about Gwyneth Paltrow’s…let’s just say it rhymed with regina. After the fourth verse of the song, Sam leaned over my son Gabriel and whispered into my ear, “Don’t tell my granddaughter about this.”

When I met with his children to plan his service of death and resurrection, his daughter said to me:

“Over the years, Daddy had a lot of hard, trying times. The two wars, Korea and Vietnam, left him with scars beyond healing and nightmares without consolation. My mother’s illness exhausted him. And then the strokes and all that rehab. But when he looked back on his life— Daddy told me so just before he lost his power to speak— all he could see was the hand of God.”

If the final lines of David’s prayer are the most consistently mistranslated of the psalm, then the modifier at the beginning of verse six is but another instance of an interpretative stumble. Often translated as “surely,” the Hebrew work is ʾak. The modifier is both intensive and restrictive. It means not surely but only.

Only goodness and mercy are in pursuit of me.

Just as the Shepherd is before me, only God is behind me, questing after me.

Astonishingly— offensively, perhaps— David looks over his shoulder and back on his life and confesses that he can see the goodness and the steadfast love of Jesus Christ in every single circumstance of his life.

As Old Testament scholar Dale Ralph Davis summarizes the verse, “The expression is remarkable. There is a certain chemistry in believing faith that can combine brute facts with buoyant faith.” Or, as David prays in Psalm 119, “You are good and do good.”

Only good.

God’s goodness and steadfast love have you surrounded.

Of course, most renderings of Psalm 23 hedge. Instead they read surely not only. They do so, quite simply, because modern translators balk at affirming what the scriptures so straightforwardly attest; namely, God is the will which wills in all things.

Providence is the word Christians use for this hidden, ordered provision guiding our lives and all of history to God’s desired End. “All things are subject to divine providence, Thomas Aquinas writes, “not only in general, but even in their own individual selves.” Absent the Lord’s hand, the whole universe would be meaningless. Lacking all order, it would have no rationale or telos. Apart from God’s providence, the very act of prayer would be pointless.

As Robert Jenson explains the stakes in the psalm’s closing claim:

“Behind all the nihilisms of modernity is the vision of our world as a deaf and dumb apparatus, within which we live but to which our converse is irrelevant.

We have turned our society and our individual psyches into alien and silent prisons. In its participation in this self-alienation much of the American church has become simply unbelieving, disguising its abandonment of faith by doing other things— meditation, self or group therapy, activism and community organizing etc. and calling it Christianity. Our “progressivism” and “conservatism” are but the atheist branches of the same capitulation before a dead universe.

And it is all a delusion.”

If everything is not within the LORD’s providential grasp, God would be unable to save us. Either God’s providential love has us surrounded, leading and pursuing us. Or our redemption is in jeopardy.

Thereupon David’s prayer raises the inevitable question. Does the LORD’s providence exclude our personal willing? Quite the opposite. After all, David’s assault against Bathsheba trespassed the LORD’s will for David, but they did not permanently interrupt God’s providential guiding and pursuit of him.

David is neither a pawn nor an automaton.

As Jenson explains the dynamic of divine providence and creaturely will:

“The history God is making with us has the freedom of a good story, and it is a freedom that is there even for the Father and the Son, and therefore is a story full of turnings and detours. As we live in that story, we may be sure of the character of its outcome, but we do not know where God may be hiding around the next corner.”

And then to illustrate his point, Jenson points to the Parable of the Good Samaritan:

“The Samaritan does not expect a beaten-up Jew in his way nor the Jew a Samaritan benefactor. [After he has providentially arranged their encounter] the one hiding on the side of the road to see what will happen next is God.”

God is waiting to be surprised by what we do next.

Just so—

Faith in God’s providence does not nullify our works or our willing.

Faith in God’s providence begets perseverance.

“Providence,” my friend Brad East writes, “is a secret whispered from one martyr to another until the end of time.”

He continues:

“Providence, in short, makes a promise. It says that your life may sometimes seem like one long crucifixion, but at the end of it lies an empty tomb. A belief in providence takes God at his word no matter how dark life becomes.”

Providence takes God at his word.

Which word?

“The LORD your Shepherd is in front of you, and only tov and hesed— nothing else— are chasing after you.”

No matter how life looks, the three person’d God's got you surrounded.

A few days after I baptized Megan, her parents made use of the business card I’d stuffed into their go-bag. They called me. Despite what her grandmother may have thought about me as a priest or a preacher, the family had neither to bury their baby.

And so the following week I followed 64 West across the border to a graveyard near Summersville, West Virginia. In the place where a headstone later would be placed, the parents had pressed into the soil a photograph of themselves with Megan, holding her in the delivery room. You could not tell from the picture that anything was amiss in the world.

Casting earth upon her tiny casket, I commended her to the LORD, saying from the Prayerbook:

“Into your hands, O merciful Savior, we commend your child Megan. Acknowledge, we humbly beseech you, a sheep of your own fold, a lamb of your own flock…Receive her into the arms of your hesed .”

By way of benediction, I read the twenty-third psalm— the “forever in the house of the LORD” one. Afterwards, as we walked back to our cars, Megan’s grandmother said to me, “Thank you for praying the right version, preacher.”

I smiled, “I think it’s a distinction without a difference.”

She crinkled her brows like I had uttered nonsense.

I said:

“Think about it. The LORD disallows David from building the Temple because God wants to remain in the Tent of Meeting until he guided history to the appropriate point for his House to be built. David knew— a God so in command of our lives…you might as well pray in the here and now as though the promised future has already happened.”

Again, she just started at me, still skeptical of the groggy, rookie chaplain she’d seen at work in the delivery room.

“Think of it this way,” I tried, “Pray right now like you’re already playing in the Father’s House with a toddler named Megan. Because the LORD is after us and there isn’t a damn thing that’s ultimately going to keep God from getting what he wants.”

Then she grabbed ahold of me and cried tears that were not altogether sad.

A month or so after we buried her, Megan’s parents found me in the hospital cafeteria. They had come to Charlottesville because they wanted me to know that they were trying to become pregnant.

There is a certain chemistry in believing faith that can combine brute facts with buoyant faith.

“Megan would want a little brother or sister,” Megan’s mother told me over coffee, “She’ll be anxious to meet him or her.”

God is waiting to be surprised by what we will choose to do next.

As my friend writes, the doctrine of providence does not make our lives easy to interpret. The doctrine of providence makes the living of our lives endurable.

Endurable.Some sermons are aimed at the one who preaches.I spent part of this week in a hospital in the Blue Ridge Mountains where we own a home. We’re preparing to list the house for sale. I was in the midst of a short, simple task when a thunderclap headache waylaid me— the third such one this week. Concerned, I checked my blood pressure which had spiked to Chernobyl levels, well past the edge of a stroke. My head felt like it was about to crack apart like plastic Easter egg.

Fun fact: High blood pressure and brain hemorrhages are a side effect of my chemotherapy.

When I complained to my oncologist on Friday about the treatment’s rigor, he replied candidly, “The plan is to do this until it stops working so buckle up; the alternative is death.”

He’s from Belgrade; I can only assume his bedside manner gets lost in translation.

Look—

If I had the power to choose, this is not how I would script my life. Nevertheless! I trust that it is not a story without a plot. And trust me, I get it. I know that if you’re only looking at what’s right in front of you— in your life, in the news, in the world—if you’re only looking at what’s immediately before you, it can be hard to see the tov and hesed of God.

But when I alter my gaze and widen the frame, when I look further out on the horizon to the future— the Father’s House— and when I look over my shoulder at all that is behind me, I’m with David.

It’s all— somehow— only the goodness and steadfast love of Jesus.

Sure, I may have a turd in my lap right now.

Nonetheless, God’s got me surrounded.

The doctrine of providence makes the living of our lives endurable.

Such perseverance is the reason Mark fixes the Transfiguration at the pivot between Jesus’s ministry and his inexorable march to the cross. The LORD reveals Jesus— as he truly is— to Peter, James, and John; so that, they might persevere through his Passion.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer preaches:

“It is a great gesture of grace that the same disciples who are to experience Jesus’s suffering in Gethsemane are now able to see him as the transfigured Son of God, as the eternal God. Hence the disciples go to the cross knowing about the resurrection. In that sense, they are exactly like us. We should bear the cross in the same knowledge of the End.”

The doctrine of providence makes the living of our lives endurable.

This is why the LORD gives us a similar vision, week after week, Sunday after Sunday. The LORD grants us a glimpse not of Jesus leaking glory but of Christ incarnate as loaf and cup. He is here, with you; so that, you can endure, moving forward in your story and trusting that one day, in the Father’s House, you will live happily ever after.

Don’t believe me?

Skeptical maybe?

Then step forward in faith, and come to the table. Bread and wine are our altar call. Here, it’s all only goodness and mercy on the menu.

Come.

Sure, some of us are hurting. In a ditch. Waiting for rescue. Or just help.

Come.

If we are the Body of Christ, then God’s got you surrounded.

And he is waiting to be surprised by what you do next.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers