Jason Micheli's Blog, page 22

January 5, 2025

Pain Seeking Understanding

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Psalm 23

For exactly a decade I have suffered a rare, incurable cancer in my blood. After a harrowing initial year of surgeries and treatments, my doctors have kept it bay over the last several years.

But then, just before Labor Day, I noticed a lump on my neck. A couple of days later, I found more on my throat and the back of my head. The next day, I traced the ones that had swelled on my groin. Shortly thereafter, one of my oncologists had me sit down on the examining table. She snapped on latex gloves and began to move her fingers over my body like she was reading Braille. As she did so, I felt my heart start to race. Beads of sweat broke out across my forehead. My pulse quickened. When she finished checking the lymph nodes on my groin, I sat up and almost fell over, feeling dizzy and short of breath. As she pulled off her gloves and sat down on the round, wheeled stool to wake the computer and look at my lab work— for lack of a more precise medical term— I cracked up.

Like Humpty Dumpty.

I broke down.

I fell apart.

Into pieces.

To the doctor, I mumbled with alarm, “I don’t— I don’t feel so good. I think I’m sick.”

She stood up. She looked at my blanched face. She felt my sprinting pulse.

“I don’t think you’re sick,” she said with a kindergarten teacher’s empathy, “I think you’re having a panic attack.”

And as my blood work materialized on the computer screen, my oncologist wrapped her arm around my heaving shoulders like I was a boy in trouble on the playground.

A week later a guy with a bunch of letters behind his name diagnosed me with letters of my own.

Four letters: PTSD.

Apparently, incurable cancer takes a toll on the mental health.

Back in the fall, my therapist ended our initial session with a question, "How in the hell did you make it this long without cracking up.”

I held out my hands like he was a panhandler and I was proving to him that my pockets carried no cash. But that was not a good enough answer. So he waited, his patient gaze boring holes in me. And then he repeated his question.

“How did you make it this long without coming apart?”

I shrugged my shoulders.

“Prayer?” I ventured.

“Jesus?”

Of course, I realize prayer and Jesus are embarrassingly pious responses. And the truth of the matter is that I was but reaching for any answer that would quell his scrutiny of me. I assumed prayer and Jesus might be the sort of reply he would expect from a reverend. And I guessed correctly because he took me at my word and nodded and moved on to chide me for using humor to avoid my feelings.

“Prayer…Jesus?”

Again, I intended it as nothing more than a nonchalant response to avoid his trenchant gaze, and I thought no more about it for months.

But then—

After having sat for a long time with the Bible’s most beloved text, it dawned on me, like an epiphany, that although I had been sitting on my therapist’s couch, I had nonetheless managed to stumble over what the church fathers called the regula fidei.

The rule of faith.

Much like the doctrine of creation, the image of the LORD as shepherd reverberates throughout the scriptures and is a key part of the Bible’s primary discourse. In fact, to so address God is to invoke the doctrine of creation and confess that nothing that happens happens apart from the shepherding will of God. This is the precise if offensive claim Jacob makes when he becomes the first of the patriarchs to address God as a shepherd. On his deathbed, Israel blesses his youngest son Joseph, saying, “The God before whom my ancestors Abraham and Isaac walked…has been the shepherd of all of my life to this very day.”

Like a lost sheep, the image of the shepherd wanders all over the Bible.

When God’s people plead for a king like the other nations, the LORD submits to their request by giving them a sheepherding boy from Bethlehem. Meanwhile the prophet Jeremiah is the first to turn the image of shepherd against the rulers of Israel:

“Woe to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my

pasture! says the Lord…The days are surely coming, says the

Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he

shall reign.”

Whereas Jeremiah indicts the royals as wicked shepherds, Jesus compares God to a foolhardy one who abandons the ninety-nine for the single lost sheep. Having compared God to a shepherd, Jesus likewise reveals himself to be the Shepherd, “I AM the Good Shepherd,” Jesus declares in the Gospel of John, “in that I lay down my life for my sheep.” Not only is Jesus the Good Shepherd, the scriptures culminate in a complementary if not contradictory vision of Jesus as a slain lamb. “Then I saw a Lamb,” the seer John reports, “looking as if it had been slain, standing at the center of heaven’s throne.”

He is both lamb and shepherd.When the prophet Ezekiel finally breaks forth with a word of gospel, through him the LORD utters a perplexing promise. The LORD's ultimate, eschatological shepherd will be both himself, the LORD, and in the line of David, “I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep…And I will set up over them one shepherd, my servant David.”

He is simultaneously both LORD and David.The imagery redounds throughout the scriptures; therefore, for King David to pray “The LORD is my shepherd” is no more novel than addressing God as Maker of Heaven and Earth. The image is a sheer given in the scriptures. What is surprising is not that David prays “The LORD is my shepherd;” what is astonishing is that David’s prayer is scripture.

That David prays “The LORD is my shepherd” is not startling.That David’s prayer is scripture is bewildering.Around the same time I met with my therapist for the first time, I visited Mike Moser for the last time.

I held his hand. I rubbed his tumored legs. I stroked his head. And I read a couple of psalms to him. As I read the twenty-third psalm, I watched Mike squint with fierce concentration, his lips turning over each of the scant verses like a jeweler appraising a diamond. Then I handed over the goods to Mike; I gave him absolution for the entirety of his sins. Finally, I knelt beside his reclining hospital chair. I took both his hand and the hand of his hospice worker, and I led us in prayer. I prayed for the Holy Spirit to help him die well, tethered to the promise of his baptism and the hope of the resurrection. When I finished praying, the three of us all together said— even Mike managed to get it out with some volume, “Amen.”

We did not say, “This is the word of God for the people of God.”

But we could have.

We could have.

As mysterious, as preposterous, as this may sound, it is nevertheless the straightforward conclusion demanded by the presence of a prayerbook in the middle of the scriptures.

The Bible contains one hundred fifty prayers called psalms. Of them, David authored nearly half. Asaph, the choir-master appointed by David, contributed a dozen. The levitical family of the children of Korah wrote another twelve of the prayers. King Solomon composed two. Heman and Ethan, temple musicians, each produced a prayer.

That’s a lot of people not named Yahweh.

And yet, their prayers to God are simultaneously God’s word to us.

Once again—

That David prays “The LORD is my shepherd” is not startling.

That David’s prayer is the word of God is bewildering.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer puts the puzzle, “There is in the Holy Scriptures one book that differs from all other books of the Bible in that it contains only prayers.” Psalm 23 is so familiar and the Psalter itself is so beloved and so oft-quoted that we miss the baffling fact of the Psalms: there is a prayerbook in the Bible. The scriptures are God’s word to us. Yet by definition prayers are the very opposite; prayers are human words addressed to God.

Bonhoeffer writes:

“The Holy Scriptures are, to be sure, God’s Word to us. But prayers are human words. How then do they come to be in the Bible? Let us make no mistake: the Bible is God’s Word, even in the Psalms. Then are the prayers to God really God’s own Word to us? That seems difficult for us to understand.”

How is that for an understatement?

Of course it is difficult to understand!

It is a paradoxical. It is contradictory. It is an impossibility. Prayer cannot be both our words to God and God’s word to us. Prayer cannot be human and divine. anymore than a shepherd can be a lamb.

Or a lamb the Shepherd.

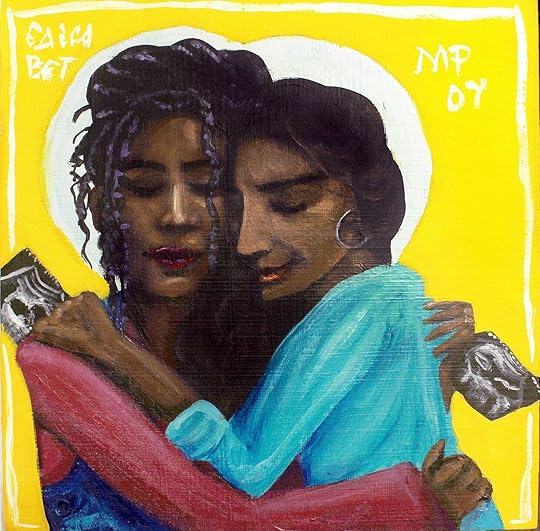

Ellen Charry teaches theology at Princeton. In her commentary on the Book of Psalms, she suggests that the subtitle for the Bible’s prayerbook could be “Pain Seeking Understanding,” for such is the life of prayer. Personal experience made her a perceptive reader. Her husband Dana, a psychiatrist, died of lung cancer in 2003. Never a smoker, his diagnosis was sudden and his decline swift. After his death, Charry published an essay entitled on lament. In the essay, as what she called “a case-study in trust and lament,” Charry included some of the letters her husband wrote to family and friends as he navigated “the vale of death’s shadow.”

What’s remarkable about his letters is how even as he documents his ongoing frustration and grief that his prayers have not been answered in the manner he hoped, Dana Charry nonetheless experienced a new and profound connection to and intimacy with the LORD Jesus Christ.

On Epiphany in 2003, Dana Charry wrote:

“Dear Friends and Family,

How we wish we could send you a Christmas letter this year filled with joy and hope…Indeed…it seems clear that God’s answer to our prayers— so far— is not the one we were hoping for. This is a test of our faith which we will have to ponder in the months to come. This much we know…even as we pray seemingly unanswered prayers, we experience more love, joy, and the presence of God than in our lifetimes. This crisis has brought our daughter Tamar back into the heart of our family, and without her love and humor we would both be a wreck. We are truly in God’s hands.”

Two weeks after Epiphany, following a setback, Dana Charry updated his friends and family:

“How I wish I could have spared you this news. And yet, how very happy I am that you know, and that you are storming heaven, praying on my behalf. I pray every day that God may hear the fervent prayers of his people, and I do believe he does as the prayers of his own Son. Pray that Jesus wraps his hands tightly around all the organs of my body, and with his loving gaze and healing touch drives out all my sickness. I have never felt so vulnerable; but also, I have never felt so completely in God’s hands.”

A month later, he wrote:

“I have a new theological approach to this, which is helping me a lot. My old concept of God not being responsible for this illness led to too much frustration and lack of confidence. I now believe — perhaps because I sense him so— that God for some absolutely inconceivable reason has determined that this should happen. He’s shepherding us in the midst of this fray. It’s a tough theology, but either way is tough. Keep me in your prayers. In all our praying there is only the prayer of Jesus.”

As the season of Epiphany turned to Lent and Dana Charry neared the End, he wrote:

“I imagine you all are eager to know the outcome of my recent tests…It’s a mixed picture. And not quite the miracle we had hoped…When I let myself think about it, I do wonder what God has in mind with all these problems. The one good which we can see coming out of this is the outpouring of love; therefore, there must be other good God intends that we cannot yet see. I feel very close to Jesus. I am not struggling emotionally or theologically at all. But, I need your prayers right now because I feel this experimental treatment is the last chance for me. If you are inclined pray the psalms with your prayers, you might pray Psalm 23. I have recited it daily for the past seventeen years, praying it with Jesus.

In God’s Love and Peace, Dana and Ellen”

Praying it with Jesus.

Simply—

To pray is to find the way to and speak with God.

But Jesus alone is the way to God; no one can approach the Father except through him.

Just so, we can pray only in Jesus Christ— that’s the rule of faith.

And only with Jesus are our prayers heard.

As Paul reminds the church at Rome, we know not how to pray, but when we pray it is the Spirit of Jesus who prays in us. This is why, even as his prayers went unanswered, Dana Charry nevertheless experienced a deep and overwhelming intimacy with Christ.

Whenever Dana Charry prayed, it was Jesus praying in him.This is true of King David as well.As the Book of Hebrews attests, “When Christ came into the world, he said, “Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired…but a body. in burnt-offerings and sin-offerings you have taken no pleasure.” That’s Psalm 40, a Psalm of David. But according to the New Testament, the speaker of David’s prayer is Jesus.

Again: “For this reason Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers and sisters, saying, I will proclaim your name to my brothers and sisters, in the midst of the congregation I will praise you.” That’s the Psalm just before Psalm 23. It’s another Psalm of David. Or is it? Scripture again identifies the speaker of David’s prayer as “great David’s greater Son.”

He is both lamb and shepherd.

Yet again, the Book of Hebrews proclaims, “As the Spirit of Jesus says, “Today, if you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts as in the rebellion, as on the day of testing in the wilderness.” That’s Psalm 95, a Psalm of Jesus.

As Bonhoeffer writes:

“In the prayers of David, it is precisely the promised Christ who already speaks. The same words that David spoke, therefore, the future Messiah spoke in him…even David prayed not only out the personal raptures of his heart, but from Christ dwelling in him. To be sure, the one who prays remains himself, but Christ dwells in him and with him. The last words of David the old man express this very thing, “The Spirit of the Lord speaks through me, his word is on my tongue.”

From there Bonhoeffer anticipates the question, “How is it possible that a human being and Jesus Christ pray simultaneously?”

He answers:

Only because Jesus is the LORD can we pray “The LORD is my shepherd.”“It is the incarnate Son of God, who pours out the heart of all humanity before God and who stands in our place and prays for us whenever we pray. He has known torment and pain, guilt and death, more deeply than we have. Therefore, our prayer is the prayer of the human nature assumed by Christ. It is really our prayer, but since the Son of God knows us better than we know ourselves, and was truly human for our sake, it is also really the Son’s prayer. Prayer can become our prayer only because it is first his prayer.”

In other words, not all the psalms are from David, there are at least five other authors. Not all the psalms are from David, but they are all from Jesus Christ. Thus, your every prayer is one to which we could respond, “This is the word of God for the people of God.”

Late this summer, near the end of a visit with Mike, I told him that I would pray for him. And Mike’s squinted eyes betrayed the gears turning in his mind. Finally he said to me, “You know Jason— sometimes I rather think prayer is useless.”

“Useless?”

And Mike elaborated, “So often—more often than not, in my case— prayers appear to go unanswered. What’s more, most of what I need medical science can supply. So yes, sometimes I think prayer is rather useless.”

I smiled and patted him on the knee.

“You got it all backwards, Mike.”

He resumed squinting at me.

Eventually he gestured towards me, inviting me to lay my cards down.

“It’s not a question of whether prayer is useful or useless to us,” I said, “That’s like asking what role God plays in your life— that’s bass ackwards. The right way to think about it is what role do you play in God’s life. It’s irrelevant whether prayer is useful or useless to us. The point is: prayer is useful to God.”

“How so?”

“In the conversation that is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, God wants to include you, Mike. Think about it. The Maker of Heaven and Earth’s life is incomplete without you. God wants to hear from you. In fact, he’s so determined to hear from you that he gets Jesus to pray in you so that not even you can screw it up. God wants to talk with you, Mike. The LORD doesn’t want to be your genie in a lamp; he wants you in his life. If you ask me, that’s beyond a better gift than anything I might think to request from him.”

Mike’s squint turned to a smile.

“Would you pray with me?” he asked.

“How in the hell did you make it this long without cracking up,” he asked.

“Prayer…Jesus.”

As though my words were not my own, I had tumbled out with an answer far more correct than I knew.

January 4, 2025

Encounters with Silence

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Hi Friends,

Here is the final session of our discussion of Karl Rahner’s Encounters with Silence with Chris Green. I regret I was unable to join the group the past two weeks, but I hope to return with our next study.

On that note, we will not meet this Monday night. We will begin a new study the following Monday, January 13th. We will be reading and discussing Robert Farrar Capon’s The Mystery of Christ: And Why We Don’t Get it.

If you’ve not read Capon before, you’re in for ride. He writes for a lay audience, and he aims to make reading him as fun as the gospel. The Mystery of Christ is gospel proclamation in the form of pastoral counseling sessions. Get a copy and join us 1/13 at 7:00 PM EST.

Show Notes

Show NotesSummary

This conversation delves into the themes of vocation, calling, and the nature of ministry within the context of Advent. The speakers explore the emotional and spiritual dimensions of waiting for God, the importance of attentiveness in ministry, and the tension between the present and future aspects of faith. They reflect on the significance of self-perception in understanding one's calling and the communal aspects of living out one's vocation. The discussion culminates in a reflection on the fulfillment of Advent and the ongoing presence of God in the lives of believers.

Takeaways

Vocation is a calling that everyone has, even if they don't recognize it.

Self-perception can hinder our understanding of our calling.

Attentiveness to others is a vital aspect of ministry.

The sacrament of attentiveness helps people feel alive.

Jesus embodies the true sacrament in our lives.

Our calling is to give, not just to consume.

Advent invites us to live in the tension of waiting and presence.

Fulfillment in faith is about recognizing God's ongoing presence.

We must clear distractions to see God's work in our lives.

Living surprised by joy is a key aspect of faith.

Sound Bites

"The opposite of consuming is giving."

"Jesus is the only true sacrament."

"We are living surprised by joy."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 3, 2025

The Wise Men's Ass

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The star pointed the way to Christ.

The Wise Men’s worship of him pointed to the greatness of their faith.

After our children’s Christmas Pageant this Advent, I sat on the altar with the cast members and answered their questions at random, a tradition I like to call “Midrash in the Moment.” This season they posed to me a surprising number of questions about the Wise Men.

One such question:

“I know they rode camels, but did the Wise Men have donkeys too?”

Like Leo McGarry, I did not accept the premise of her question and pivoted. Only later did I discover that the church father Origen interprets the passage assigned for Epiphany by way of Balaam and his talking ass in the Book of Numbers.

In Homily 13, Origen proclaims:

“If Balaam’s prophecies were introduced by Moses into the sacred books, how much more were they copied by those who were living at that time in Mesopotamia, among whom Balaam had a great reputation and who are known to have been disciples of his art? After all, it is reported that from him a race and institution of magicians flourished in parts of the East, which possessed copies among themselves of everything that Balaam had prophesied. They even possessed the following writing, “A star will rise out of Jacob, and a man will spring from Israel.” The magi had these writings among themselves, and that is why, when Jesus was born, they recognized the star and they understood, more than the people of Israel, who despised hearing the words of the holy prophets, that the prophecy was being fulfilled. Therefore, based only on these writings that Balaam had left behind, when they knew that the time was near, they came looking for him, and immediately worshipped him. And to declare the greatness of their faith, they venerated the small child as a king.”

The star pointed the way to Christ.

The wise men’s worship of him pointed to the greatness of their faith.

In Homily 15, Origen preaches on Numbers 23.10, “And let my seed become as the seed of the just.” He proclaims:

“This could indeed be understood even about that Balaam, according to the fact that those Magi who came from the east and first worshipped Jesus seem to have been of his “seed,” whether by physical descent or traditional instruction. For plainly it is a fact that they recognized that the star that Balaam had predicted would “rise in Israel” (Numbers 24.17). And so they came to worship the king who was born in Israel. Nevertheless, it will correspond with that people according to the things that we have said above; for it is not so much themselves, as their seed that will become like the seed of the just, namely, of those who have been justified in Christ by “believing from the Gentiles.”

Finally, Origen sees in the Magi’s flight from Herod— as the Holy Family flees into Egypt— an allegory to the drama of salvation. Origen points this time to Numbers 23-24:

“After this it is written, still concerning Christ, that “God led him out of Egypt.” This seems to have been fulfilled at that time when, after the death of Herod, he is called back from Egypt. The Gospel indicates this when it says, “Out of Egypt, I have called my son.” To some these words seem to have been taken from this passage in Numbers and were inserted into the Gospel, but to others they seem to have come from the prophet Hosea. However, it can also be understood as an allegory, that after he went to the Egypt of this world, the Father led him and took him to himself, so that he could make a way for those who were to ascend to God from the Egypt of this world.

His glory, therefore, is like that of a unicorn.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 1, 2025

The World was Made for the Circumcision of Mary's Boy

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Luke 2:15-21

Remember, Christmas is a season not a day: Merry Christmas!

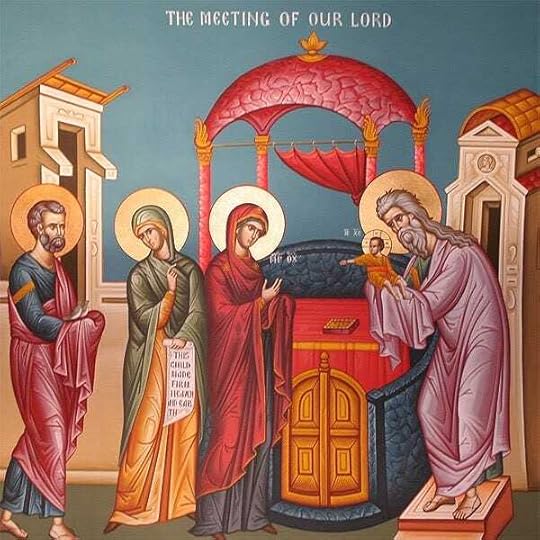

And on the liturgical calendar for the twelve days of this short season, today is Holy Name of Jesus, in which the church recalls the naming and circumcision of Jesus.

According to the Lord’s command to Abraham in the Book of Genesis, Mary and Joseph have their baby circumcised on the eighth day after his birth. In so doing, the child becomes an official participant in the people of Israel and receives his name, Yeshua— the name first given to them by the angel Gabriel.

Thenceforth, the Holy Family travels nine miles from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, up to the temple to fulfill two obligations prescribed by the Torah. First, Mary and Joseph must redeem their firstborn son. Because every firstborn child and every firstborn creature belongs to God, they needed to be redeemed from God. Clean animals, such as sheep or goats, would be sacrificed. Unclean animals, like donkeys, would be redeemed by offering a clean animal in its stead. The redemption price for a firstborn son, according to Numbers 18.16, was fixed at five shekels. It’s one of the only prescribed offerings in the Torah that’s not scaled according to wealth or poverty.

After making Jesus a participant in the people of Israel by means of circumcision, Mary and Joseph venture to the temple in Jerusalem in order to make Jesus a participant in their family.They make an offering so that God’s child might become their child. The second obligation Mary and Joseph perform in Jerusalem is purification. Bearing a son meant that Mary— and anything Mary touched— was ritually unclean for seven days. To avoid defilement from his wife, Joseph needed to immerse himself daily in the temple’s miqveh. Having given birth to a son, the Torah also forbid Mary from handling “holy things” (for example, alms for the poor or a tithe to the temple) for a period of thirty-three days. At the end of this period, Mary could come to the temple with an animal offering. As set out in Leviticus 12, the sacrifice required of a poor woman was two doves.

So thirty-three days after his birth and twenty-five days after his redemption from the Lord, Mary and Joseph journey through the massive colonnaded courtyard that marked off the Court of the Gentiles and walk up to the animal vendor stalls set up alongside the towering outer wall of the temple. They purchase two doves, walk through the Court of the Gentiles, past the low wall through which only Jews were permitted, and up the steps to the inner courts of the temple.

Taking her two doves in one arm and her month-old baby in the other arm, Mary enters the Court of Women through a side door where a Levite waited to take Mary’s offering to a priest who waited for it in the Court of Priests. At some point, as they rove from the chaotic Court of the Gentiles to the busy vendor stalls to the crowded Court of the Jews and finally to the Court of Women, Mary and Joseph, their baby and doves in tow, bump into Simeon. Not only has the Holy Spirit led Simeon to this encounter, the Holy Spirit commandeers Simeon’s lips and the old man prophesies that in their baby God is making good on his promise of consolation first given through Isaiah. That Torah did not permit Simeon to enter the Court of Women meant that Mary encountered him just before her sacrifice; in other words, Mary entered the Court of Women and made her offering with Simeon’s words still ringing in her ears that somehow she carried in her arms not just two doves and more than an ordinary baby.

Circumcision is the sign of the covenant.

Circumcision is the sign of the covenant that the Lord makes to Abram, “I will be your God and you will be my people.” Circumcision is the sign of the “covenant in your flesh.” The rituals for the redemption of a first born child and the purification of its mother are acts of fidelity to that covenant. Luke tells you five times that Mary and Joseph did everything in obedience to the Torah. Meanwhile, according to Simeon, their child is the fulfillment of that covenant.

Everything in Luke 2 is about the covenant.Circumcision is the sign of the covenant. Redemption and purification are acts of obedience to the covenant. Jesus is God’s commitment to the covenant made flesh.

The postpartum particulars, the shekels and miqveh, doves and defilement, may strike us as strange today. So much so, we miss entirely a far stranger feature of the Bible and fail to ask a most basic question.

What kind of odd God makes a covenant?A covenant is a promise.

To make a promise, the promise-maker must address an other.

But to so address an other means the promise-maker is interested and invested in the other’s existence.What makes the gods God is precisely the absence of any such personal concern. For Aristotle, God is the Unmoved Mover. God doesn’t send rain when you pray for rain; God established systems whereby secondary causes may or may not bring rain. For Plato, God is simply the One. For Nietzsche, there is such an infinite qualitative difference between Creator and creature that to suggest God loves Jenny is analogous to you claiming you cherish the ant crawling under the pew at your feet. For pagans, today and in antiquity, it’s blasphemy to imagine God speaking to Abraham or wrestling with Jacob or showing Moses his backside. Pagan religion, then and now, cannot abide communication between Creator and creature; therefore, there can be no covenant. Without communication, there is no promise.

What kind of odd God makes a covenant?

A covenant is a promise addressed to an other.

To make a promise to an other, the promise-maker must have an other.

But for God to have an other to whom he can address a promise, God must be a God who creates. By contrast, the Greeks believed creation was eternal, that it had always existed. A God who makes a covenant must be a God who instigates an other other than himself.

This is why Jews point to a tiny Hebrew word in the Genesis account of creation, tov.

“And God saw that it was tov.”

Not simply good.

Tov means “good for.”

Creation is good for covenant.

God creates for the purpose of making a covenant.As the second Book of Esdras puts it unabashedly:

“It was for us that you created the world.”

Believers sometimes get up on the how or the when of creation without realizing that the why of creation is the entire reason scripture bothers to proclaim the story in the first place.

As Karl Barth writes:

“Creation is the outer basis of the covenant and the covenant is the inner basis of creation.”

The whole reason for light and darkness, morning and evening, sky and stars and every creeping creature upon the earth is for God to deliver the consolation of Israel in Jesus Christ.

Everything is made for the baby in Mary’s arms and for us to be in him.What kind of odd God makes a covenant?

A covenant is a promise the binds the promise-maker to an other.

To make a promise to an other, the promise-maker must acquire a shared history with the other.

But for God to inaugurate a joint history with an other, God must accept no other future than with this other.

A covenant is like a wedding vow.

The promise creates a shared history and a mutual future that would not have been apart from the promise.Which means— pay attention— the promise makes God an actor in the history God authors.

This joint history and shared future is why the God of the covenant is simultaneously both the author of the history he makes with creatures and one (or more) of the dramatis personae of that history.

As the theologian Robert Jenson summarizes:

“Israel’s scriptures are rife with figures that are actors in the history determined by the Creator yet who turn out to be the same Creator God.”

Think of the “Angel of the Lord” on Mount Moriah who stays Abraham’s hand from cutting Isaac’s throat. In the story, the Angel of the Lord turns out to be the Lord himself just as the pillar of fire that accompanies the Israelites in the wilderness is none other than the same God who met Moses in the Burning Bush, the same God who sits invisibly above the cherubim throne.

“God is in heaven and you are on earth,” Solomon waxes in the Book of Ecclesiastes. Not exactly.

In making a promise, God commits himself to being both the author of history and an actor with us within that history.

Trinity is nothing more than a shorthand way of narrating the fact that there is no other God but the God who acts within the very history he authors. God acts as Father, God acts as Son, God acts as Holy Spirit. The good news of great joy is that God is not abstract deity.

God is a participant in his own Providence.The true God is not immune to time; but rather, God’s faithfulness to his promise is the how of God’s eternity.

As Jenson says, “God is roomy.”

God has room to accommodate all your stories within his story, casting himself as a player in all your lives.

Take Luke’s conclusion to the nativity as a case in point.

As Mary and Joseph approach the Temple in Jerusalem, the Shekhinah of the Lord dwells invisibly in the holy of holies, yet, at the same time, there’s God the Holy Spirit taxiing Simeon to the exact spot where he will encounter Mary and Joseph with words the same Spirit will lay on his lips about the child in her arms. The baby in Mary’s arms also happens to be the eternal Son of God made flesh.

In making a promise, God commits himself to being both the author of history and an actor within that history.

Because now— because of the promise— God has as much stake in your future as you do.

Therefore, the story in Luke’s Gospel of Mary and Joseph and Simeon is no different than any of our stories.

Because God is a God who makes covenant, there is no distinction between the world of the Bible and our world. God is invisibly enthroned above and beyond, the author of your story, yes. But God is also with you, a cast member in your story, graciously—sometimes painfully— in ways seen and unseen, driving your story to the future God desires for us all.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 30, 2024

Encounters with Silence

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

I apologize for the delay.

Here’s last week’s session with Chris.

Don’t forget to join us live tonight at 7:00 EST. HERE is the link.

Summary

This conversation delves into the themes of silence, grief, and the nature of God as explored through music, prayer, and personal reflection. The participants discuss the significance of encounters with silence, the role of prayer in grief, and the complexities of faith during Advent. They explore the paradox of seeking God amidst feelings of abandonment and the importance of community and connection in spiritual journeys. The dialogue emphasizes the need for courageous honesty in faith and the transformative power of complaints as a pathway to intimacy with God.

Takeaways

The essence of a well-played game is more important than the outcome.

Grief can only be expressed through prayer after loss.

Encounters with silence are deeply personal and transformative.

Advent invites us to reflect on the God of the living and the dead.

Courageous honesty in faith allows for deeper connections.

Silence can be filled with meaning if we attend to it.

The communion of saints offers comfort in times of loss.

Seeking God often involves navigating paradoxes in relationships.

Complaints can lead to intimacy and deeper understanding in prayer.

Love must be clean and free from unhealthy attachments.

Sound Bites

"You haven't really sent me away from you."

"Your heart is bigger than ours."

"We are made for play."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 28, 2024

Cancer is NOT Funny

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

An update:

Just a month shy of ten years ago, I woke up from emergency surgery to my wife patiently explaining to me that I had a rare, incurable cancer. The likelihood of its recurrence is a certainty my oncologist has routinely drawn on the back of a box of latex gloves. I sailed past the standard deviation a couple of years ago.

Beginning in late summer, I started to feel unwell.

A few night sweats became watery eyes. Watery eyes became lumps in my throat. Then lumps all over. Of late, my abdomen and chest have hurt like a bitch.

As I’ve told a few essential folks, “I feel like I’ve been kicked in the nuts all over my body.”

After a biopsy, CT, and PET scans the past few weeks, on Thursday I was presented with a radioactive image of my body that looks depressingly similar to the copy I was handed a decade ago.

I start treatment today— a “miracle” that brings night sweat producing anxieties I won’t bother with here.I’ve reposted the below several times, part of a sermon I preached. I truly do believe it; though, I can’t escape noticing that the people (Gary, Steve, Everett— all better men than me) for whom I reposted it didn’t make it. I’m fu@#$%^ batting 0.00 on this post. Still, I’m re-upping it because A) I believe it’s true and B) it’s been a scary, stressful few months for my wife and boys.

If it’s the case that the true God, the Father of Jesus, is persuadable, then, I’d be remiss not to ask you to pray. For me. And for them:Ali

Alexander

Gabriel.

Ten years ago I wrote a book about all this shit. That Tony Jones, my friend who edited— and titled— the book, remains a uniquely trusted friend is grace. I hate the book’s title now with a righteous hatred. Cancer is NOT funny.

A couple of year ago, I was in my truck, driving to the office, when the theologian Stanley Hauerwas called me. He’d been ill and had undergone surgery in England, and I’d left him a message inquiring about his health and spirit. That morning on the way to church, he called me back and before I could even say hello, his gravely Texas accent barked out, “Jason I can’t piss, and it’s just so damn painful.”

As I pulled into the church’s parking lot, he described all the complications he’d suffered following what should have been a routine procedure.

I listened.

But I knew that Stanley is not the sort of Christian to be satisfied with a preacher who offers nothing but active listening.

So I said to him, “I’ll pray for you, Stanley.”

“You damn well better do it now,” he grumbled, “I’m miserable, in agony.”

I cleared my throat and was about to begin praying when Stanley interrupted me.

“And Jason?”

“Yes, Stanley?”

“If you’re not going to pray for God to heal me, then, hell, just hang up the phone right now already.”

I laughed and I prayed to God for just that and when I was done he said, “Thank you. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

In Genesis 28, Jacob prays without tact, humility, or self-awareness. Jacob makes unseemly requests of God. And God does just as Jacob asks: Jacob is clothed and fed and sheltered and reconciled.

Nothing that happens in the world happens apart from the free willing of God.Yet…God is persuadable.Several years ago now, I was at the infusion center to receive the Neulasta injection that bookended my every round of chemo. An old woman sat directly across from me, a red-orange tube running from a bag to her chest. She wore a blue scarf with peacocks on it around her small, bony head. Her face looked so sunken and her skin so stretched and translucent that guessing her age felt impossible. She greeted me—exhausted, her eyes only half open—with a distinct prairie accent when I sat down and cracked open my book.

I didn’t get past the first page.

She started to cry—whimper really—from the sores her chemo-poison had burnt into her mouth and tongue and throat. Beseeching the nurse, she pleaded, “make the pain go away.” She kept on like that, inconsolable, with no concern for what I or anyone else might think about her. In a different-size person you’d call it a tantrum.

Seeing her there, spent and defeated, I felt compelled to do the only work I could for her. I prayed. Quietly, under my breath, just above a whisper, my lips moving to the petitions. And when I finished, I made the sign of the cross over her.

“You religious?” the man in the next infusion chair asked me.

“Sort of, I guess.”

He went to wave me off, dismissively, but then remembered his arm was taped and tethered to tubes and the tubes to an IV pole. He’d been on the phone on work calls almost the whole time I’d been there. A gray tie that matched his hair hung loose from his unbuttoned collar.

“You really think that stuff works— prayer?”

He said it in a tone that suggested no believer anywhere at anytime had ever wrestled with such a question.

“Well,” I replied, “If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.”

If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.

He nodded seeming to appreciate that I had not evaded the stakes at the heart of his question.

“I’ve got a partner,” he said, “in my firm. He prays. He says he does it because it changes him. Like, he prays for patience and the practice of praying makes him more patient. Like meditation I suppose.”

I nodded and smiled wryly.

“You’d never know it from the way a lot of Christians talk about prayer,” I said to him, “But the content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.”

The content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.

He didn’t follow me so I said, “You’d be surprised how many people pray who do not believe in prayer.”

“A lot of them are ordained,” I added.

He laughed, and then he went back to his work.

A couple of minutes later he sat his phone down on his lap and raised his hands in a “What gives?” gesture.

“But how?” he said, “I mean, come on! You’re telling me that you think we can change God’s mind about God’s will?”

I smiled a wide and crazy smile.

“It’s totally crazy, isn’t it?” I said, “It’s tremendously preposterous— to say nothing of presumptuous— but that’s the claim. That’s the claim Jews and Christians make (at least the ones who haven’t lost their theological nerve). If the claim is wrong, then the gospel is a lie and prayer is nothing but a bunch of hot air.”

And then I pointed at the exhausted, whimpering woman across from me.

“The claim is not only that we can tell the Father what he ought to do about her; the claim is the Father will listen and may heed us.”The old rabbis considered Jacob the father of faith.

How?

Jacob is the father of faith, the old rabbis attested, because Jacob made a verbal reply to the God who addressed him.

He prayed.

He prayed a petitionary prayer.

He prayed, “Father, give me this, that, and the other, and you can be my God.”

The law commands faith.

The creeds describe faith.

Prayer is the act of faith.Prayer is the act of faith, and, put the other way around, a sure sign of a lack of faith is a reluctance to pray boldly.

Just imagine an anthropologist from outer space, observing for the first time, Jews and Christians engaged in prayer.

What would she think?

Surely, she would conclude that we were engaged in dialogue with one on whom we are utterly dependent but one we could nevertheless influence.

It’s quite obvious.

Yet if asked a question like, “Do you really believe your prayer can change God’s mind?” many believers balk at the unambiguous implications of our practice.Our evasions are not dictated to us by scripture.The God of the Bible hears the cries of his people as slaves in Egypt and is moved to deliver them. The God of Israel is talked off the ledge by Abraham, who convinces the Lord not to destroy every citizen of Sodom. The God of Abraham is persuaded by Jacob to go beyond the promise and also provide for Jacob’s room and board and meal plan.

The God of the Bible is persuadable.Prayer is elementary but it’s offensive.

Think about it—

When we bring God our petitions, we presume to advise the Maker of All that Is about how best to order the universe. That’s what we’re doing; that’s what we presume. We don’t pray simply because such prayers form us. We don’t pray to accrue any merit. We’re not practicing mindfulness.

No, we pray to tell the Creator how to govern his creation.

We presume that the cosmic course of history can be brought to respond to our concerns.Such presumptions are presumptuous.

Now to get overly philosophical or polemical but all of you have been shaped deeply by the Enlightenment’s conviction that we inhabit a mechanical universe whose processes (called nature and history) are immune to petition.

The great temptation, one which traditions like Methodism have largely fallen prey, is to reconstruct a God appropriate to this supposedly indifferent, mechanical universe.

Thus:

A God too impersonal and static, impassible and distant, to be pleased by our praise or persuaded by our petitions.

But if the gospel is true, if scripture is reliable, if faith is possible, then all of this is backwards.

This is the day the Lord is making.

If bold, presumptuous petitions are implausible in our world, then it is the world we misunderstand not God. Which means, we’re worshipping an idol and we ought to repent and turn to the true God.

The Persuadable God.

In his recent book, Peace in the Last Third of Life: A Handbook of Hope for Boomers, PaulZahl writes,

“I got a sincere but somewhat pathetic prayer request from an old friend last year, asking me to pray for her friend’s stage- four breast cancer. My friend asked me to pray for good medical care for the person, for patience and endurance for the person’s husband, for a sound mind among her family that would know when it was time to “pull the plug,” and for a loving exchange of ideas concerning the inevitable funeral. I wrote back, asking if the possibility of praying for remission in this case were on the table. She wrote back saying that it had not come up.

Then later, during the coronavirus pandemic, I received a series of prayers from the chaplains of the Episcopal prep school I attended. Not one of the prayers included a single note of supplication for the virus itself to be restrained or for healing to be given to any who had contracted it.

I used to be diffident about praying for the remission or healing of a physical illness, let alone of a mental incapacity or disturbance. I would pray for the sufferer’s acceptance and serenity much more often than for God’s intervention and victory.

I was wrong.”

Paul Zahl may have been wrong, but he is hardly alone.

When I first got cancer several years ago, I was astonished at the apparent unbelief in prayer by those who do it. Every person was sincere. It just goes to show how little sincerity has to do with discipleship.

“l’ll pray that God gives you strength,” people would tell me.

“I’m praying that God will give your doctors wisdom,” pastors told me.

“You’re in my thoughts,” far too many Christians told me.

Your thoughts? What in the hell good are your thoughts going to do? I’m dying. Why don’t you pray for God to make it not so?! Why don’t you attempt to persuade God to heal me?

Some did so pray.

And I am grateful for their prayers.

As Robert Jenson says of Christ inviting us to piggy-back onto his own prayers to the Father, “This is to be taken seriously.”

We can dare address God with our petitions because Jesus has invited us into his conversation with the Father.

God is so gracious.

He hasn’t just made a decision about you in Jesus Christ. On account of Jesus Christ, he’s willing to listen to you. He doesn’t just allow he invites our views to be heard and weighed in his care of the universe, exactly as a parent listens to and considers seriously the views of their children.

“Our expressed opinion,” says Robert Jenson, “is an essential pole of the process of God’s decision-making.”Because of Jesus, because you’ve been incorporated in to him, because you’ve been invited in, because his Father is now your Father too, the life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

The life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

God wants you to speak up. Make a motion. Voice your opinion.

The claim implicit in Christian prayer is astonishing. Most will not believe it.

Quite simply:

To pray to stake a claim over the care of creation.To pray is to presume co-determination of the universe.To pray is to participate in Providence.Any lesser claim evades the clear implications of scripture and makes prayer nothing but an empty practice of piety.

There is perhaps no stronger indictment of the Church in a secular age than the fact that this needs to be said clearly and without hesitation:

Prayer accomplishes things.When we pray for someone, when we petition God on their behalf, we intend thereby to accomplish something for them.

Prayer is the work grace gives us to do. It is our work in the world on the world. It is our work in the world for the world’s future.

Prayer pulls us into the working out of God’s governance of the world. Prayer is our participation in Providence. In Jesus, the Father has given you a say in how his history will come out.

So, let us pray.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 26, 2024

The Miracle of Christmas: Grace as Judgment

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously! It’s Christmas.

Here’s a piece I wrote for Mockingbird a few years ago.

Merry Christmas!

So much of what the angel Gabriel tells Mary harkens to other passages from the Bible. “Favored one” is the way the haggard priest, Eli, greets Hannah before she learns of her own miraculous child. “Overshadowed” is the manner in which the Old Testament describes God’s presence abiding with the Israelites as they wander through the wilderness, making Mary’s womb a new ark of the covenant, while Mary’s obedient resignation before an angel, “Let it be with me according to your word,” matches almost word for word what her boy, when he’s all grown up, will plead before a cup to the Father in Gethsemane.

Mary’s child, however, is something altogether different from the miraculous babies born to Sarai or Hannah. An unexpected, miraculous birth isn’t the same thing as a virginbirth. With Mary, it was as if the angelʼs message, Godʼs words alone, had flicked a light in the darkness of her womb. Life from nothing — that is the difference. Not from Joseph or anyone else. From nothing God creates life. Inside her. The same way God created the heavens and the earth, ex nihilo [from nothing]. The same way God created the sun and the sea and the stars. The same way God created Adam and Eve. From nothing. As though what she carried within her was creation itself. The start of a new beginning. To everything. A genesis and an ultimate reversal all in one.

Jesus’s birth by means of the Virgin Mary is one of the claims the creed dares us to profess, but what exactly did the ancient Church want us to believe about it? Are we to believe it as the biographical bits of his origin story? Or, are we, as fundamentalists have done in the modern era, meant to lean into the supernatural aspect of Christ’s birth? Is it, as it were, a statement of Jesus’s biological beginnings?

In a wonderful section of Church Dogmatics I.II, “The Miracle of Christmas,” Karl Barth reminds us that, from the time of exile in the Book of Isaiah to what the Church Fathers made of Isaiah’s prophecy coming true in Christ, the virgin birth has always been understood more as a theological — not a biological— assertion. In keeping with the very nature of Hebrew prophecy, Barth notes, the virgin birth is the judgment of God.

On Good Friday, God’s judgment manifests as grace. In Advent, God’s grace manifests as judgment.

The revelation of the grace of God, made flesh in Mary’s womb, is also the revelation of the judgment of God, made concrete in Joseph’s absence.

Joseph contributes nothing to the conception of Christ. Unlike Abraham or Elkanah, the husbands of Sarah and Hannah respectively, God excludes Joseph — and thus, all the rest of us— from the conception of new creation. That Joseph is rendered a passive bystander to the miracle of Christmas is God’s judgment upon the whole history of humankind. Because we’ve twisted the world into our image, the Maker of Heaven and Earth will not allow us even to pitch in and participate in the birthing of its redemption. All our comforting pieties about the freedom of the will crash against the manger in Bethlehem. “If Emmanuel is true,” Barth writes, “the miracle is done upon man. It is man who is the object of sovereign divine action in this event. God himself and God alone is Master and Lord. This cannot be stated strongly enough, exclusively enough, negatively enough against all synergism or even monism.”

The bumper stickers and Carrie Underwood songs have it more wrong than we know. We’re not even God’s co-pilot. That’s the judgment revealed in Joseph’s absence. That’s the judgment we confess when we profess, “born of the Virgin Mary.”

Today, the newspaper tells me that over a million children, abandoned by the White House, lie on the precipice of starvation in Afghanistan. This new week of Advent begins a week after yet another school shooting, a plague of gun violence perpetuated, surely, by our hardened hearts and our fealty to barren deities. And another famous and powerful man has been brought low by accusations of assault and impropriety. The virgin birth tells us that Almighty God looks at our ways in the world, says, “Thanks but no thanks,” and gently pushes Joseph to the side of the stage.

The clause “… born of the Virgin Mary” is less about the beginning of Jesus and more about the end of humanity. Having proved ourselves an unreliable covenant partner of God, we now can only receive the passive righteousness of one in whose creation we cannot boast. As Karl Barth writes,

In the virgin birth of Christ there is contained a judgment upon man. In other words, human nature possesses no capacity for becoming the human nature of Jesus Christ, the place of divine revelation. It cannot be the work-mate of God. If it actually becomes so, it is not because of any attributes which it possessed already and in itself, but because of what is done to it by the divine Word, and so not because of what it has to do or give, but because of what it has to suffer and receive — and at the hand of God.

The virginity of Mary in the birth of the Lord is the denial, not of man in the presence of God, but of any power, attribute or capacity in him for God. If he has this power — and Mary clearly has it — it means strictly and exclusively that he acquires it, that it is laid upon him. In this power of his for God he can as little understand himself as Mary in the story of the Annunciation could understand herself as the future mother of the Messiah. Only with her [“behold the hand-maid of the Lord”] can he understand himself as what, in a way inconceivable to himself, he has actually become in the sight of God and by His agency.

The meaning of this judgment, this negation, is not the difference between God as Creator and man as a creature. Man as a creature — if we try for a moment to speak of man in this abstract way — might have the capacity for God and even be able to understand himself in this capacity. In Paradise there would have been no need of the sign [of the virgin birth] to indicate that man was God’s fellow-worker. But the man whom revelation reaches, and who is reconciled to God in revelation and by it, is not man in Paradise. He has not ceased to be God’s creature. But he has lost his pure creatureliness, and with it the capacity for God, because as a creature and in the totality of his creatureliness he became disobedient to his Creator. To the roots of his being he lives in this disobedience.

It is with this disobedient creature that God has to do in His revelation. It is his nature, his flesh, that the Word assumes in being made flesh. And this human nature, the only one we know and the only one there actually is, has of itself no capacity for being adopted by God’s Word into unity with Himself, i.e., into personal unity with God. Upon this human nature a mystery must be wrought in order that this may be made possible. And this mystery must consist in its receiving the capacity for God which it does not possess. This mystery is signified by the virgin birth. [emphasis added]

As Barth taught in his homiletics class at the University of Gottingen, a course Barth offered out of his alarm that the school’s official teacher of preaching was also an early adopter of Nazism — another example of “Joseph” and his history — “Grace is always ‘despite’ and not ‘because of’ the human condition. God’s gracious action is never ‘consequently’ but always ‘nevertheless.’ It is life from the dead and the justification of the ungodly not the reward of the righteous.” This is as true at the annunciation as it is in the passion. The one-way love of God is simultaneously the judgment of God upon our ways in the world. The “miracle” of Christmas— at least, a miracle of Christmas, is that this judgment, rendered upon all of us in the person of Joseph, comes (nevertheless!) as a mercy. God might have looked at the world and said, “Thanks, but no thanks,” but he simultaneously embraced the world by coming to save it. Joseph, whom God has elected to exclude, will (nevertheless!) get to hold Mary’s child in his arms. Every bit as much as the shepherds, the sign is for him.

And, I wouldn’t be a preacher if I didn’t apply the pronoun. It’s for you too.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 24, 2024

Love is a Battlefield

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Christmas Eve— Luke 2.1-12

Two years ago during the twelve days of Christmas, I baptized an infant into Christ Jesus the LORD. By water and the Spirit, the drooling, drowsy baby became a part of the body of the boy born to Mary.

After the baptism, as kids ran around the sanctuary and their grown-ups chatted, a child pointed at a nativity displayed on a side table in front of a church window. Two of the shepherds had been knocked to their sides, perhaps bowled over by their astonishment at the heavenly host. Or maybe the shepherds had fallen over, exhausted from sprinting to the Holy Family from their far away fields. The magi, I noticed, had arrived at the manger approximately a week too early. Meanwhile, someone familiar with animal husbandry had placed one of Bethlehem’s sheep on top of the other. Likely the same culprit was guilty of attempting to yield some hybrid creature from the coupling of a cow and a donkey. A Lego stormtrooper, I noticed, stood hidden in the angelic ranks, blaster aimed at the angel Gabriel.

The girl pointed at the chipped manger holding the ceramic child as though a pearl in a shucked oyster.

“Who is that?” she asked me.

“That’s Larry,” I said, “St. Nick’s eldest by a first marriage.”

She looked at me like a stranger with candy, “No.”

“No,” I conceded, “That’s…”

I was about to say, “That’s the baby Jesus.” But I caught myself and stopped short. I thought this might be my only opportunity to afflict this child with the unmitigated audacity of the promise. So I decided to complicate Christmas for her.

“Who is that?” I asked.

She nodded, her curiosity genuine.

I pointed at the fired-and-glazed child— holding, I noticed, a small, gold crucifix in his tiny fist.

“That baby,” I said in a hushed, conspiratorial whisper, “is God.”

She turned from the creche. She looked at me, waiting for an explanation, but I did not have one. We do not have one. So I repeated myself.

“That baby is God.”

She wrinkled her nose and crinkled her lips and furrowed her brows, as though I had just posited the most preposterous assertion. And then, like air escaping from a pierced balloon, she let out an incredulous laugh.

“No!” she giggled.

She is not the first so to laugh.

Long before Luke’s nativity became church canon, pagan critics lampooned it. In his work The True Word, Celsus, a second century Roman philosopher, mocked the claims Christians make at Christmas:

“How can the Logos be God, who feeds like a babe at breast? How can the Beginning of all things have a beginning in time? No god travels down a birth canal. No god hides in bread and wine. No god suffers and dies. Deity does not have a mother and an executioner. Gods don’t do that!”

Of course, the unmitigated audacity of the promise goes even further. The mystery of the incarnation is not only that Mary’s finite womb contains the infinite. The mystery is yet as well that Mary’s ostensibly finite, flesh-and-blood boy is eternal. We mark the mystery with magi and mangers, shepherds and stars, angels and despots, but we need not rely upon Luke and Matthew. To ponder the mystery unveiled in Bethlehem, we could literally turn to any place in scripture.

For example—

Six hundred years before the shepherds were “keeping watch over their flocks by night,” the prophet Ezekiel is shown the heavenly prototype of the temple’s cherubim throne. And on the throne in heaven, as the source and energy of its glory, “was an appearance that was the figure of a man.”

“How can the one seated on the throne in heaven— God’s heaven— look like a man?” the ancient rabbis wondered.

Ever since Mary first pondered the mystery in her heart, classic Christian interpretation has answered the rabbis’s question thusly, “Because the one seated on the throne in God’s heaven is a man, Jesus of Nazareth. The man seated on the throne in God’s heaven is the boy in Bethlehem’s manger.”

As the theologian Robert Jenson writes:

“This stark proposition of the incarnation offends all normal religiosity, which at this point will want to talk about metaphors or symbols or figures; it is nonetheless the defining theological affirmation of Christianity…the second triune identity and the man Jesus of Nazareth are but one person. As the Apostles' Creed presents the matter…there is no way to speak of God that does not refer to the man Jesus, and no way to speak of the man Jesus that does not refer to God.”

Last year during Advent, following the children’s Christmas pageant, I sat at the altar and answered the children’s questions at random. It’s a tradition I like to call “Midrash in the Moment.” Thankfully, no child asked me to explain the word virgin. A little girl, however, did ask me at the end a question whose answer ought to inspire still greater amazement and incredulity than Mary’s pregnancy ex nihilo.

“How old is Jesus?” she asked me.

“Well,” I said, “He’s not 2,023 years old.”

After the service, the girl came up to me in the fellowship hall. Cupcake in hand, she said to me, “You didn’t answer my question.”

“I didn’t?”

She shook her head.

“You said Jesus is not 2,023 years old but you didn’t say how old Jesus is.”

I leaned down towards her and I whispered, like I was letting her in on a secret— because I was, letting her in on a mystery.

“He is before all things,” I whispered, “Jesus was before was was.”

She furrowed her eyebrows like she’d just sucked on a lemon.

She looked at me like I had a poopy shoe, “That’s not a very clear answer.”

“Well, it’s the one we got.”

The man the prophet Ezekiel sees seated on God’s throne “shimmers,” scripture says. He shimmers because sight is always uncertain when it cannot fix objects in the present.

We need not the magi’s myrrh or Caesar’s census to tell the story. The scriptures are replete with the mystery we unwrap at Christmas.

Take another instance—

In very first pages of the Bible, Abraham’s slave-girl, Hagar, grieves in the wilderness after she and her son, Ishmael, having been cast-off by Abraham’s wife Sarah. God hears Hagar’s weeping. And the scriptures report that an angel of the LORD speaks to Hagar, consoling her. The angel first refers to God in the third person, “God has heard the voice of your boy.” But then, without any break in his speech or formula of citation, the angel speaks of God in the first person, “I will make a great nation of him.”

Once again, the ancient rabbis wondered, nearly as incredulous as the pagan Celsus, “How can one who is other from God speak as God?”

And again, ever since the magi fled King Herod, the church has answered, “Because the one who consoled Hagar and her child is both an other from God and God; he is Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim, the second triune identity.”

Sight is always uncertain when it cannot fix objects in the present.

Since the fourth century the church has celebrated Christ’s nativity on December 25, yet the mystery of the incarnation does not fit so easily on a timeline. Christmas is not Jesus’s first appearance in the scriptures. This is the mystery we profess when we confess that God’s proper name is— and always has been and will ever be— Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Word does not become flesh in the sense that he becomes someone he was not. As the evangelist John proclaims in his own nativity account, “He— that is, Jesus— was in the beginning with God.” Somehow, Jesus is both begotten of the Father before all creation and born to Mary.

As Robert Jenson puts the faith’s puzzling entailments:

“The Bible violates our notion of time more or less on every page…That Mary is the Mother of God indeed disrupts the linear time-line or pseudo time-line on which Westerners automatically— and usually subconsciously— locate every event, even the birth of God the Son; but that disruption is all to the theological good.”

Time is not a straight line through the present.

Time is a helix, wrapped around Jesus, tighter than swaddling clothes.

As Charles Wesley puts it in the carol, the child in Bethlehem is the “heaven-born, prince of peace.”

The mystery of Christmas is not simply that the LORD meets us in Jesus. The mystery of Christmas— and, just so, the gospel— is that the child born to Mary is a protagonist in Mary’s own scriptures. He’s the man on the throne. He’s the comfort to Hagar. He’s the voice that stays Abraham from slaying his only son.

What’s revealed hidden in the little town of Bethlehem, is that God has never been otherwise than Emmanuel. God-with-us. And if this is a claim to which we have no explanation, then we can nevertheless dare a question.

Why?

Why does the Father again and again violate all of religion’s rules for deity by meeting us— in time— in the Son?

If we cannot unpack the how of God’s who, can we at least venture a why?

For the first seven years of his life, Daniel Solomon slept upright. He had no other option, sharing a crib with another child his age in an orphanage in Romania.

During the day, one team of workers fed and cleaned Daniel and the other hundred orphans, all of whom lived in the same room. A graveyard crew covered the night shift. Daniel never learned the names of any of the adults who tended to him.

Daniel did not go to school.

Daniel did not go outside.

Except to go to the bathroom, Daniel did not leave his crib.

And Daniel did not yearn for a family.

He had no such notion.

“It’s like, a kid who never eats chocolate doesn't know what chocolate tastes like,” Daniel recalls, “I didn't know what a family was to think about it at all.”

One day Heidi Solomon received a magazine in the mail at her home in Cleveland, Ohio. It was from an adoption agency and included in it, among hundreds of photographs, was a picture of Daniel.

“I just remember telling my husband,” Heidi remembered, “I’m like, I think this is our son. So it was just kind of weird. Like, for some reason, his picture just, shimmered.”

Heidi had always planned to adopt children with her husband Rick. A special education teacher, she knew welcoming Daniel into their family could pose difficulties. The ease of their first six months together defied her expectations.

Then came Daniel’s birthday in March.

“I remember at the beginning of March Daniel said, they don't have March in Romania because I never had a birthday before.”

Until his eighth birthday, Daniel had never confronted the idea that he had been born.

“After my birthday,” Daniel says, “I started thinking that they were my biological parents, and how I was really mad at them that they put me there for seven and a half years.”

Daniel’s confusion begat a powerful hatred of his parents, an anger that took on a logic of its own. His tantrums became tornadoes of rage. They started to fear their son. They called in social workers and specialists, several of whom left bleeding, needing medical attention.

But Daniel saved the worst of it for his mother.

He hated her.

And he took pleasure in her pain.

“There was a time,” Daniel remembers, “where my dad hired this bodyguard to come to our house because my mom didn't feel safe with me.”

Rick and Heidi ferried Daniel from one psychiatrist to another, religiously heeding their advice to no discernible effect.

No less than two specialists told Heidi that her son would never love her.

Heidi remembers one case manager who sat them down and said to them, "This is what’s going to happen. Daniel's going to hurt you. You're going to be in the hospital. He'll be in juvenile detention, and your husband's going to leave you.”

So Heidi sought out more about aggressive treatments for attachment disorder, resorting to a therapy with a controversial history practiced by a doctor in Virginia.

Offending the norms of nearly all his colleagues, the psychiatrist prescribed what at first sounded preposterous to Heidi. The doctor mandated that Heidi and Daniel spend months upon months bound together, side by side, never more than three feet apart.

The physician’s goal was to heal Daniel by re-creating the bond that never occurred.

“For months, I didn't go to school,” Daniel recalls. “She stopped her job. When she would go to the bathroom, I would be right outside the door. When I went to the bathroom, she'd be right outside the door. The only time she was not next to me was when I was sleeping. Like, literally, that was it.”

In addition to the physical bond between them, the doctor required the mother and son spend large amounts of time making eye contact. And Daniel was not allowed to ask Heidi for things he wanted. Like a baby, he needed to learn that his mother would provide for him what he need. Whenever Daniel resisted treatment, he was subjected to yet another program-dictated activity— time-ins. Every time Daniel did something bad his mother's response would be to spend more time with him, even closer together with him.

“Like, we would sit on the couch and I would hug him,” Heidi says, “That was, like, his punishment.”

Initially the radical treatment made Daniel worse.

But then something happened.

“I think it was around the third week,” Daniel says, "that I actually-- like, I was with her more. I think I realized maybe for the first time, that my mother loved me.”

Parts of the treatment continued until Daniel was thirteen years old.

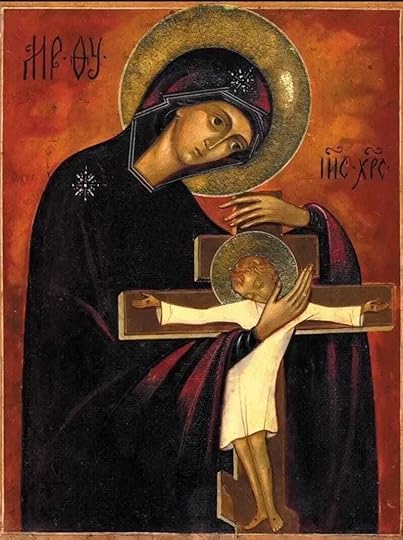

For example, every night, for twenty minutes, Heidi and Rick had to hold Daniel and talk to him soothingly, cradling him like a newborn baby. Even though their boy was quite big at that point, the doctor ordered them to make their arms a manger for him.

Slowly—

Heidi’s and Rick’s hands-on, in-your-face, unconventional love began to transform Daniel.

Reflecting upon their journey, Heidi told a reporter, “If you're the kind of person who actually needs love— really needs love— chances are, you're not the kind of person who's going to have the wherewithal to create it. Creating love is not for the soft and sentimental among us. Love is a battlefield.”

Of all the animals the LORD has made, we are the only ones who know not how to be creatures. That is, quite unnaturally, we do not love God easily. Quite unnaturally, we do not love God reliably. Quite unnaturally, we do not love God well— certainly not with our whole hearts and minds and souls and strength.

We have an attachment disorder. This is what the Bible calls sin. And it’s why the translation for the Greek word for salvation— sozo— is healing.

We have an attachment disorder.

We have a Father and a family for whom we know not even to yearn!

We have an attachment disorder. And in order to heal us, in order to re-create the bond that should have occurred but did not, God resorts to a drastic remedy. Violating all of religion’s rules for deity, from the very first pages of the scriptures the LORD meets us in time and space. He binds himself to us in the flesh. Again and again, he gets hands-on and in-our-faces. Even more preposterously— even though he’s way too big for our laps, the Ancient of Days goes so far as to make himself an infant, to be cradled in our arms.

Around the same time that Daniel was coming to love his mother and father, the rabbi of their synagogue called to tell them that Daniel had won an award for the valedictorian of the confirmation class. As part of the award, Daniel was invited to give a speech to the congregation.

Daniel told his parents that he wanted his words to be his gift to them, that he wanted his words to be a way of giving himself to them.

By the time he got to the end of this speech, Daniel was shaking, struggling to keep his voice under control. His final words were for his Mom and Dad, and they were the first time he’d spoken those words to them.

“I love you very much.”

We cannot unpack the how of God’s who.

But the why is straightforward.

What’s unveiled in bands of cloth, the mystery of Christmas, is that even more so than Heidi and Rick, God has determined his eternal identity to hear from you those same five words, “I love you very much.”

We cannot explain the how of God’s who.

But the why!

The why of God’s who is right there in the carol, “And fit us for heaven to live with thee there.”

So come to the table.

God is so desperate to attach you to himself he makes himself not just a child at Mary’s breast but an object in your hands and on your lips. The bread and the wine are the way he teaches you that he will provide for you what you need.

Which is to say, the table is our altar call.

The loaf and the cup are how you get born again.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 23, 2024

Slow Down!!!

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Here’s a sermon for the Fourth Sunday of Advent by my friend Dr. Ken Sundet Jones.

Luther Memorial Church, Des Moines, Iowa

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father

and the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

Today’s gospel reading alludes to something we rarely think about when we hear the Christmas story from Luke on Christmas Eve. When Mary and Joseph went to Bethlehem because of the Roman empire’s tax laws, it was likely not the first time she’d laid eyes on the little town that the carol says lay so sweetly among the hills above the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. Luke tells us today that this young woman, engaged but pregnant, went to visit her older relative Elizabeth in the hill country. Like the Hill Country of Texas south and west of Austin and my home territory of the Black Hills out in South Dakota and our own Loess Hills here in Iowa, the Judean hill country is a distinct geographical and geological territory. If you said you were going to the Hills, I’d guess people back then knew what you were talking about, even up north in Nazareth in Galilee at the source of the Jordan River.

But when Luke points out the Judean hill country and the town of Bethlehem later this week on Christmas Eve, he’s got more in mind than simply giving us an arrow on a map with the words “you are here” next to it.

In his account of Jesus’ birth in the very next chapter of his gospel, Luke lists the names of the rulers in place when Jesus was born: the Roman emperor Caesar Augustus and Quirinius who was the governor of Syria. Luke did the same thing two Sundays ago when he gave an even longer list of rulers in his story of John the Baptist as a precursor to Jesus. Most of us don’t know anything about Quirinius or about Lysanias the ruler of Abilene (that’s in Syria not in Texas). So those names stand out.

But because we’ve heard about Bethlehem every Christmas and sung carols about it and had kids act out the story in church pageants, we skim over the fact that Bethlehem has significance. Bethlehem isn’t a random location. In fact, the entire history of God’s chosen people, the Israelites, led both to that little town and to Mary’s womb, because Mary is the embodiment of everything that God had been doing in the world throughout history and that culminates in that place.

In our Old Testament reading today, the prophet Micah tells the Israelites that a coming king will arrive to judge and redeem God’s people who had become corrupt to their bones and faithless in their hearts. The situation was nearly hopeless.

Israel’s kings had no fealty to God. Men were marrying pagan Canaanite women and raising families who didn’t know the Lord. The temple’s priests accepted bribes. And the people’s offerings were literally lame: sickly lambs, blemished calves, and paltry coins in the coffer. God was serious about the creation he’d made and the people he’d chosen with his blessing, and neither the seriousness nor the blessing were offered back to him. In the next chapter Micah announces exactly what God’s vision for our lives looks like: “He has shown you, O people, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you, but do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8).