Jason Micheli's Blog, page 24

December 10, 2024

"Mary is our connection to Jesus according to the flesh; Joseph is our connection according to identity."

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Mary is our connection to the God-who-is-human according to the flesh.

Joseph is our connection to him according to identity.

December 9, 2024

What Would be the Alternative to an Incarnate God?

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

“The ideas about God that we Jews identify as Christian are not innovations but may be deeply connected with some of the most ancient of Israelite ideas about God.”

Christmas is not merely the Messiah's birthday.

Christmas is the Feast of the Incarnation.

Christmas is the Nativity of God.At Christmas, the church dares to announce a revelation; namely, the Maker of Heaven and Earth is a Jew who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly. Mary, the Council of Ephesus decreed in the fifth century, is the Theotokos, the God-bearer. Jesus is the God-who-is-human. His finite flesh contains the infinite. Of course, this claim immediately begets the question the creed attempts to answer.

How is it possible?

As stubbornly as it persists, how is not the best question to ask about incarnation. Because God is the Condition that conditions all conditions, we cannot condition what God can do based upon what we take to be the givens of the world.

God is the Condition that conditions all conditions; therefore, how questions are seldom the best questions to ask when it comes to God.

For example:

The dead don’t rise— that’s a given of the world.

And yet, Jesus lives with death behind him.

God is the Condition that conditions all conditions. The God who raised Israel from slavery in Egypt can resurrect Jesus from the grave.

Rather than ask how—

How did God become man?

How can the finite contain the infinite?

How is it possible for Mary to give birth to her Maker ex nihilo?

Rather than ask how—Advent is the perfect occasion to inquire about the alternative.What is the opposite of incarnation?What would be the alternative to an incarnated God?If the Word did not take flesh, what sort of God is God?If the Word did not take flesh, what sort of God is God?

The genuine alternative to an incarnate God would be a God who has no spatial location whatsoever. The true opposite to incarnation would be total, absolute monotheism. If God is not incarnate, then God is sheer spirit. Corporeality would be totally foreign to a God who is spirit. The defining essence of matter is that it takes up space; therefore, if God is totally non-corporeal, then there can be no spatial location of God.

Once you understand that exactly this God— the God who is sheer spirit and occupies no space— is the opposite of an incarnate God, you realize two implications.

This God— the God who is sheer spirit and occupies no space— is precisely the God in whom most Christians in fact believe.

This God— the God who is spirit and takes up no space— is incompatible with the God of the Old Testament. The God of the Hebrew Bible does have spatial location. He walks in the Garden of Eden. He has a dwelling place in the world. From the pillar of cloud by day to the pillar of fire by night, from tent to tabernacle, from temple to the holy of holies therein, the Old Testament just is a history of God’s dwelling place in the world.

December 8, 2024

Something to Believe

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Why not? It’s Christmas!

Second Sunday of Advent — Luke 1.18-25

Baptism of Carolina Michelle Torrez Martinez

An Amazon Echo sits on our kitchen counter in between my stand mixer and the breadbox. It can tell me the week’s weather forecast. It can report my portfolio’s performance for the day. It can convert ounces to grams in a recipe. It can tell me jokes and stories, and it can do it all in the voice of Samuel L. Jackson when I request it (which is often).

During the pandemic, I asked it a simple, straightforward question.

It is also the most important question.

“Alexa,” I queried, “does God love me?”

The little blue arrow on the top of the device first lit up.

And then it circled round and around for a moment.

“I'm sure you're very lovable,” Alexa answered.

Which— let’s face it— is not true.

So I tried again.

“Alexa,” I said, taking the tone of a police interrogator, “does God love me?”

Again, the little blue arrow illuminated the cabinet space and circled clockwise around the device.

“How could anyone not love you?” Alexa replied.

“Easily,” I muttered underneath my breath.

Undeterred, I asked her again, “Alexa, does God love me?”

“People all have their own views on religion,” Alexa answered like a good secular liberal.

I rolled up my sleeves, leaned my arms on the counter, and I braced Alexa like Jules does to Ringo and Pumpkin in Pulp Fiction.

“ALEXA, DOES GOD LOVE ME?”

And again, the little blue light traced the top of the echo.

Until finally, Alexa offered the most flaccid answer of all.

“It’s more important that you love yourself.”

“It’s not,” I preached at her, “It’s really not. It's most definitely not more important that you love yourself.”

To which my son asked, “Dad, who are you yelling at?”

In his Large Catechism, the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther teaches that faith must have something tangible and visible to believe. Faith, Luther insists, must have something to which it may cling and upon which it can stand. This is why Luther asserts that baptism and faith should never be separated. Faith must have something external to you to grab onto and cling for life. Otherwise, your faith turns inward and you are left attempting to have faith in your faith, which is as effective as asking Alexa the most important question of all. Very few of us can delude ourselves for long with the lie that our faith is sufficient to save us. Indeed, for the first Protestants, the phrase “by faith alone” could just as easily be substituted with the phrase “by baptism alone.”

We are saved by baptism alone.

We do not stand on our faith.It is on baptismal faith that we stand.We do not put our faith in our faith.We cling— by faith— to the promise of our baptisms.As the theologian Gerhard Forde writes:

“Our know-it-alls assert that faith alone saves and that works and external things contribute nothing to this end. It is true, nothing that is in us does it but faith. But these leaders of the blind are unwilling to see that faith must have something to believe—something to which it may cling and upon which it may stand. Thus faith clings to the water and believes it to be baptism in which there is sheer salvation and life, not through the water, but through its incorporation with God's Word and ordinance and the joining of his name to it. When you believe this, what else is it but believing in God as the one who has implanted his Word in the water and offered it to you so that you may grasp the treasure it contains?”

What else is it but believing in God?

One of the most basic building blocks of Christian dogma is the conviction that the works of the Trinity are undivided. That is, what one person of the Triune identity does, they all do because God cannot be separated into parts. For instance, if baptism is a work of the Holy Spirit, it is also necessarily an act of the Father. And if the scriptures are clear about anything, it is that we cannot manipulate God the Father into doing what we want. Therefore, no matter what your parents may have thought they were doing in scheduling your baptism, the ultimate will behind the then-and-there of your baptism was Almighty God.

Baptismal faith, then, is faith that baptism is not the moment when we make a decision for God; baptism is the moment when the LORD applies his decision for you to you. Thus, it is God's will that here-and-now the Word would alight upon Carolina, calling into existence that which did not previously exist— a part of the totus Christus; in other words, no matter your opinions about Luke’s nativity, you are about to witness a virgin birth no less miraculous than that of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. Baptismal faith is faith that it is the Father’s will to cloth Carolina in Christ’s righteousness, and it is the LORD’s doing to do so precisely in this place, here-and-now.

You are loved by the Love in which we live and move and have our being.

You are.

You are.

But most of you cannot hold fast to that claim forever. While some of you cannot even believe it for long. And a few of you will struggle to trust it to next Sunday.

This is why faith needs something— some thing— to believe.

Faith needs something visible.

Faith needs something tangible.

Faith needs something in the here-and-now to take hold of and believe.

And because baptism is not your doing, because the will that willed your baptism is extra nos, because Christ gives himself to us in tangible, edible, visible means, we can grab ahold of God and know that, as Gerhard Forde puts it, “the one who runs the whole show is for you.”

“The one who runs the whole show is for you .”

Without these external things, faith has nothing to believe but some incomprehensible promise about the distant future or some ancient history that happened over two thousand years ago.

Sinners require more.

Faith can only be faith when it has a concrete promise to believe.

After all, even the demons and the pagans believe in the history of Jesus.

What they do not believe is that that history of Jesus is for them. Faith then is not about you believing in God. Faith is not about you believing that two thousand years ago Jesus died for you. Faith is not even about you believing that three days later God raised him from the dead for your justification.

As Martin Luther preached it,

“If I now seek the forgiveness of sins, I do not run to the cross, for I will not find it at the cross, but I will find it in the sacrament. I will find it in the gospel word which distributes, presents, offers, and gives to me today that forgiveness which was won on the cross.”

Faith is not about events a long time ago in a Galilee far far away. Faith is an everyday, existential encounter. Faith is a present-tense laying ahold of the promise God— when God speaks it to you, “This is my body given for you.”

Face it.

You are not much more lovable than me. Neither is it more important that you love yourself. And take it from me, there will be times in your life when the relevance of the most important question will knock you over and set your heart to racing.

We are all terminal cases.

In those anxious moments, secular pieties and religious speculations— which are very often the same thing— will not brighten your abyss. They will instead feel like short beds and narrow blankets.

Faith needs some thing to believe.

Faith needs a promise it can grasp like an anchor and cling for dear life.

Just so—

Water and the word, wine and bread.They provide what Luther called “the certainty of faith.”Preaching on Luke’s nativity, the church father Origen observes, “When the priest Zechariah offers incense in the temple, he is condemned to silence and cannot speak. Or better, he may speak only with gestures.”

Baptism is different than Zechariah’s muted ministry.

Baptism is the LORD’s visible word.

It is a gesture through which the triune God speaks.

In a moment, Carolina Michelle Torrez Martinez henceforth will never need to ask the question that Alexa is afraid to answer with certainty. Carolina will know the answer to the most important question of all because she will know that on the Second Sunday of Advent 2024, in this place, though means as ordinary as water, and with sinners like you for witnesses, the LORD grabbed ahold of her and declared, “You are mine; I’ll never let you go.”

From this day forward, Carolina has some thing to believe.

The rest of you need only come to the table.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 7, 2024

Jesus has a Human Nature Before He has a Human Body

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

“That Mary is Theotokos indeed disrupts the linear time-line or pseudo time-line on which we Westerners automatically – and usually subliminally – locate every event, even the birth of God the Son.”

Following my church’s children’s Christmas pageant one Sunday, I sat at the altar and answered the children’s questions at random. It’s a tradition I like to call “Midrash in the Moment.” Thankfully, no child asked me to explain the word virgin. A little girl, however, did ask me at the end a question whose answer ought to inspire still greater amazement and incredulity than Mary’s pregnancy ex nihilo.

Q: “How old is Jesus?”

A: “Eternal does not even capture the mystery.”

In declaring Mary the Theotokos (the God-bearer), creedal Christianity made a claim about Jesus far more astonishing than the church often appreciates. Mary, the Council of Ephesus decreed in 431, is the mother of the God-who-is-human; Mary is NOT the mother of a man, Jesus of Nazareth, who is united with the Logos, the second person of the Trinity. In whatever sense terms like “was” and “when” can speak intelligibly about the life of God, there never was when the Son was not.

Just so—

Jesus has a human nature before he has a human body.The incarnation is not the addition of a human Jesus to an eternal Son. A logos which exists apart from the human nature of Mary’s boy is, as even St. Athanasius insists, mythology.

December 6, 2024

From the Norwegian Sweater Office of Public Awareness

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

My friend Rolf Jacobson of Luther Seminary joined Ken Jones and me to discuss the book he wrote with his late brother Karl, Invitation to the Psalms.

Summary

In this conversation, Rolf Jacobson reflects on the profound impact of the Psalms in his life, particularly following the loss of his brother, Karl. The discussion explores themes of grief, identity, and the search for beauty amidst suffering. Jacobson emphasizes the importance of Hebrew poetry in understanding the Psalms and how they serve as a source of comfort and faithfulness in times of distress. The conversation also touches on the role of preachers in conveying the messages of the Psalms to their congregations.

Takeaways

Rolf Jacobson shares the deep personal loss of his brother Karl.

The Psalms provide comfort and identity during difficult times.

Beauty can emerge from suffering and grief.

Hebrew poetry is essential for understanding the Psalms.

Preachers should connect the Psalms to the lives of their congregants.

The Psalms express both lament and trust in God's faithfulness.

Carl Jacobson's humor and cultural insights enriched their work on the Psalms.

The Psalms are a language of faith that shapes preaching.

God's faithfulness is a recurring theme in the Psalms.

The Psalms invite inquiry and reflection on God's promises.

Sound Bites

"It's a blow unlike any other I've experienced."

"Beauty is often where the world sees ugly."

"The Psalms are the language of faith."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 5, 2024

Thy Maker's maker; thy Father's mother

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

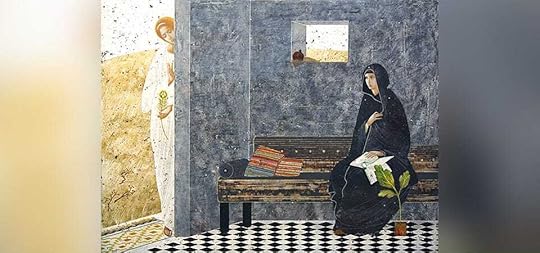

A friend of mine, Matt Milliner, teaches art history at Wheaton College. When it comes to Mary’s place in the Protestant tradition, he joked to me over Zoom:

“Imagine you’re at a party, and it’s a really great party with wonderful appetizers and delicious desserts and fantastic drinks. It’s a party with all the right people— people you love and people you want to come to love. And the party’s working. It’s all working. All of a sudden, someone bursts in from the cold, takes off their coat and says, “Hi! Hi!” And you say, “Welcome! Hello! Come in! Sit down. Have a drink. Let’s make a place for you.” And you say to one of the guests, “Get ‘em a drink! Get ‘em a drink!”

But before the drink even arrives, the guest grabs a hand full of pretzels and says, “Sorry, I’ve got to be on my way now.”

And just like that, the guest is gone.

That’s Mary in the life of the church. We invite her inside the party long enough to grab a few pretzels before we push her back out the door.”

I laughed at Matt’s Marian analogy, but he leaned forward in his desk chair and held up to me an icon of Our Lady of the Passion. Suddenly serious, he said, “How embarrassing is it that not only do we not invite Mary to all twelve days of the Christmas party, we totally ignore that Mary— this woman— is not simply a character in a seasonal festivity. She is a pivotal protagonist throughout the story of salvation.”

“Mary is a pivotal protagonist throughout the story of salvation.”

If Jesus is the Israelite made flesh, Mary is the ark of the covenant.And make no mistake, from the time of the church fathers forward it is undisputed that Mary is the Theotokos, the Mother of God. As one ancient icon titles her, she is the “Container of the Uncontainable.” Or as John Donne puts it in his poem “La Corona,” Mary is “Thy Maker's maker, and thy Father's mother.”

My friend Matt pointed again at his icon of the Our Lady of the Passion, an emphatic gesture which suggested If you don’t get, you don’t get it.

He said:

“I say this as a Protestant Christian. Don't dare think that somehow your conversation with Mary and your interest in her is in competition with your relationship with Christ…You are flirting with heresy if you do not have a doctrine of Mary as Mother of God. You are flirting with heresy if you do not have a starring role for Mary in your Christian faith.”

“You are flirting with heresy if you do not have a starring role for Mary in your Christian faith.”

And he’s absolutely right.

It was the Arian heresy in the fourth century that led to our creedal dogma. Contrary to the New Testament witness, the Arians insisted about Jesus, “There was a time when he was not.” In other words, the Son is not one substance with the Father, making Mary a mother like any other mother of a mere human.

In the history of the faith, heresy always begins by demoting Mary.December 4, 2024

Encounters with Silence

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do!

“What am I really saying, when I call You my God, the God of my life?”

Don’t forget, you can join us live next Monday at 7EST HERE.

Summary

This conversation delves into Karl Rahner's Encounters with Silence. exploring the themes of silence, prayer, and the nature of God. The participants discuss how Rahner's theology emphasizes the importance of personal experience with God, the complexities of faith, and the interplay between silence and dialogue in prayer. They reflect on the significance of Advent as a time of waiting and anticipation, highlighting the challenges and joys of engaging with the divine.

Takeaways

Rahner's theology emphasizes personal experience with God.

Silence in prayer can be both painful and purgative.

The relationship between God and humanity is dynamic and complex.

Advent invites us to reflect on the already and the not yet.

The infinite nature of God gives meaning to our finite existence.

Prayer does not have to be joyful to be valid.

The quest for God often involves wrestling with silence.

The interplay of silence and dialogue is crucial in faith.

The God who hides is also the God who reveals.

The significance of community in understanding theology.

Sound Bites

"The God who hides is the God who reveals."

"Rahner’s God is infinite."

"God does not want to be God apart from us."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 3, 2024

Why did the Friend of the Bridegroom Not a Become a Disciple?

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

The Gospel passage assigned by the lectionary for the Second Sunday of Advent is Luke 3:

In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness. He went into all the region around the Jordan, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins, as it is written in the book of the words of the prophet Isaiah, "The voice of one crying out in the wilderness: 'Prepare the way of the Lord; make his paths straight. Every valley shall be filled, and every mountain and hill shall be made low, and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways made smooth, and all flesh shall see the salvation of God.'"

John the Baptist is a prominent and essential character not only in the Gospels but in the church’s liturgy, art, and iconography. Like a familiar painting that has hung on the wall so long its beauty and detail no longer elicit astonishment, during Advent the church often rushes past John the Baptist without attending to the remarkable implications of the evangelists’s presentation of him.

The fact is as simple as it is straightforward, yet the church seldom notices it:

John baptized Jesus.But John did not become a disciple of Jesus.John the Baptist had a different vocation than discipleship.

December 2, 2024

God is One Great Fugue

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Here is our final discussion of Robert Jenson’s essay on the Last Things.

Don’t forget.

We will begin a series with Chris E.W. Green tonight at 7:00 EST based on Karl Rahner’s devotional Encounters with Silence.

For those who get the book, we will cover two chapters each week for a total of 5 Mondays.

You can join us live here.

Summary

In this conversation, the hosts reflect on themes of gratitude, the significance of music in expressing emotions, and the exploration of eschatology through Robert Jensen's work. They discuss the political language found in scripture, personal experiences with political theology, and the challenges of political discourse in contemporary society. The conversation also delves into the concepts of judgment, restoration, and the communion of saints, ultimately emphasizing the dynamic nature of God's kingdom and the importance of community in understanding eschatological themes.

Takeaways

Expressing gratitude can be challenging for some individuals.

Music can serve as a powerful medium for exploring complex emotions.

Eschatology is often misunderstood and requires deeper exploration.

Political language in scripture is significant and often overlooked.

Personal experiences shape our understanding of political theology.

The church's role in political discourse is complex and evolving.

Imagining the Kingdom of God requires a shift in perspective.

Judgment is not merely punitive but restorative in nature.

The concept of the communion of saints transcends time and space.

Understanding the last judgment involves recognizing God's desire for community.

Sound Bites

"We exist in the mind of God"

"The end is music"

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 1, 2024

Nothing Happens for the First Time

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

First Advent: Luke 1.1-25

In his clinical memoir, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, the late neurologist Oliver Sacks writes about a patient named Jimmie G, a man who is charming, intelligent, and memoryless. Over and over without ceasing, after only a few moments, Jimmie G's memory became like a slate wiped clean. Despite his salt-and-pepper hair, Jimmie existed as a perpetual nineteen year old GI.

For Jimmie, everything always happened for the first time.

Jimmie was forever meeting his doctors and fellow patients as though for the first time, and always speaking of the distant past in the present tense. And over and over, every day, Jimmie would look out the window or see a color television screen or hear a bit of news and realize the world was not as he thought it.

“Jesus Christ,” he'd whisper every time with the recognition.

“Christ, what's going on? What's happened to me? Is this a nightmare?”

Then a moment later, he would forget again.

And the next thing to happen to him would happen for the first time.

The inconstancy of Jimmie G's memory made him incapable of doing the simplest of tasks, Oliver Sacks writes. A skilled typist from his submarine training, Jimmie could punch out a paragraph's worth of copy only to find himself staring blankly at the typewriter a moment later. “One tended to speak of Jimmie instinctively as a spiritual casualty, a lost soul,” Oliver Sacks writes, “Was it possible, I wondered, for a man to be de-souled by a disease? “Do you think Jimmie G has a soul?” I once asked the nuns who cared for Jimmie. They were outraged by my question, but could see why I asked it. “Watch Jimmie in chapel,” they said. “Watch Jimmie in chapel at communion and judge for yourself.”

Though he himself was not a believer of any kind, Dr. Sacks heeded the sister's advice and went to worship to observe Jimmie G in praise and adoration. Before the altar, beholding God in loaf and cup, the doctor discovered that here was one place where not everything happened to Jimmie G for the first time.

Sacks writes:

“I was moved, profoundly moved and impressed because I saw here an intensity and steadiness of attention and concentration that I had never seen before in Jimmie or conceived him capable of. I watched him kneel and take the sacrament on his tongue, and I could not doubt the fullness and totality of communion, the perfect alignment of his spirit with the Spirit.

Fully, intensely, quietly, in the quietude of absolute concentration, Jimmie entered and partook of holy communion. He was wholly held, absorbed by a feeling. There was no forgetting, no disease then, nor did it seem possible or imaginable that there should be, for he was no longer at the mercy of a faulty and fallible mechanism, but he was absorbed in an act, a doing of his whole being, a continuity and unity so seamless it could not permit any break.”

As Christians, we are accustomed to thinking of ourselves and our fellow believers according to the (self-justifying) slogan simul iustus et peccator— simultaneously righteous and a sinner. We speak of sin as if though it’s a necessary predicate of the human situation. An odd believer like Jimmie G, therefore, may be the best analogue for the surprising possibility with which St. Luke opens his prologue to what St. Paul calls “the most praiseworthy” of the Gospels. In the purity of his motives, in his forgetting of the sins trespassed against him, and in the unity of his intentions with his actions, Jimmie G is not unlike the elderly, barren, soon-to-be-parents of John the Baptist.

According to the evangelist, Elizabeth and Zechariah “were both righteous.”Righteous not in the public square.

Righteous not in their neighbors’s eyes.

Righteous not in their own self-estimation.

Elizabeth and Zechariah were righteous before God, Luke reports, “walking in all the commandments and ordinances of the LORD.” They were righteous while not being, simultaneously, sinners. In fact, Luke adds, they were “blameless” before the LORD. As Oliver Sacks describes his patient’s predicament, "Jimmie both was and wasn’t aware of this deep, tragic loss in himself, loss of himself. If a man has lost a leg or an eye, he knows he has lost a leg or an eye; but if he has lost a self—himself—he cannot know it, because he is no longer there to know it.”

The news that any person not named Jesus of Nazareth could be deemed both righteous and blameless before God makes me feel like Jimmie G, like I’m missing a part of me less tangible than a phantom arm or a severed leg— an amputated self who knows how not to sin.

Yet Zechariah and Elizabeth are not unique.Franciscan exegetes in the Middle Ages often remarked upon scripture, “Nothing happens for the first time.” By “nothing happens for the first time” the medieval interpreters meant that events of the gospel are presaged by events with messianic portent in the Old Testament— typology, scholars call it. In particular, they referred to the way in which Elizabeth’s and Zechariah’s old age echo the unlikely child God gives to Abraham and Sarah, how Zechariah reacts to the angel of the LORD in the temple just like Isaiah had once fearfully responded, and how Elizabeth’s child is a type of the prophet-priest born as an answer to Hannah’s prayer. And when he’s grown, Elizabeth’s son, in both manner and appearance, will elicit comparisons to Elijah the Troubler of Israel.

Nothing happens for the first time.

Another recurrent feature in Luke’s prologue is the elderly couple’s righteousness under the law and blamelessness before the LORD. Zechariah and Elizabeth are not the first instance of God’s people leading faithful, sinless lives.According to the Book of Genesis, for example, "Noah was a righteous man, blameless in his generation, who walked with God.” Job furthermore was “perfect and upright, who feared the LORD, and eschewed evil.”

Nothing happens for the first time.

Zechariah, from the Order of Abijah, is one of approximately eighteen thousand priests set apart for service in the temple. Do you suppose Luke would have us conclude that he alone is righteous and without sin? Before you answer, recall how Matthew in his Gospel likewise describes Joseph of Galilee as a tsadiq, a righteous man. Mary meanwhile is full of grace, highly favored. The Bride of the fruit of Mary’s womb is also without sin. As Paul writes to the Ephesians, the Lord Jesus presented (past tense) to himself “a glorious church which had no stain of sin so that she might be holy and blameless.”

Nothing happens for the first time, “And Zechariah and Elizabeth were both righteous before God, walking in all the commandments and ordinances of God, and before the Lord blameless.”

Preaching on this passage not long after Luke first recorded it, the ancient church father Origen gripes:

“People who want to offer an excuse for their sins claim that no one is without sin. They appeal to the testimony of Job, where scripture says, “No one is clean from filth, not even if his life upon the earth has been only one day long. His months can be numbered. But they only mouth the words of this verse and are wholly ignorant of its meaning. We shall answer them briefly. “To be without sin” has two meanings in scripture. One is never to have sinned at all; the other is to have ceased sinning. If they say that the phrase “to be without sin” describes someone who has never sinned at all, then we agree that no one is without sin. All of us have sinned at some time, even though we might have become virtuous afterwards. But, if they take the phrase “no one is without sin” as denying that anyone, after he has sinned, can return to the practice of virtues and never sin again, then their opinion is wrong. For, it can happen that someone who has previously sinned can stop sinning and be said to be “without sin.”

If it is possible to live a sinless life, if it is possible to achieve righteousness under the law and blamelessness before the LORD, if God’s people prior to the incarnation lived without sin, if indeed members of Christ’s own family did so, then why does Jesus come?

If it is possible to live a sinless life, then why does Jesus come?

Very often we speak as though the purpose of Christmas is the crucifixion, that Christ’s Nativity is for his Passion, that the Son took on flesh in order for the Father to forgive the sins of humanity.

Straightforwardly, this is nonsense.

After all, if Jesus is born in order to die for our sins, then according to the scriptures there are some in Israel for whom God did not need to become incarnate, including Mary and Joseph, Zechariah and Elizabeth, Noah and Job and even David. And the Father no more needs someone to die in order to forgive sins than you do; in fact, Jesus shows up on the scene announcing the pardon of God for sinners. The absolution is what gets Jesus killed!

Nothing happens for the first time. The Father forgave sinners long before Good Friday. And some of those forgiven sinners— Zechariah, Elizabeth, et al— thereupon managed to live righteously according to the law and blameless in the eyes of the LORD. They needed not Christ’s righteousness reckoned to them. Thus, if Jesus came to die for sinners then, contrary to what he tells Nicodemus in the dead of night, Christ did not come for the whole world. If he is born to die, then he comes for some but not for all.

Just so—

The Son condescends into Mary’s womb for reasons other than the Fall.Whether we realize it or not, we affirm as much every time we utter the LORD’s proper name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. By confessing God’s triune identity, we profess that God's decision to be with us in Jesus Christ is eternal, prior to creation and before the Fall, preexistent as the Son. And thus God’s decision to be God with us is antecedent to God's determination to be for us on the cross.

The with comes before the for.Therefore, the with takes precedence over the for.It's true that Jesus saves us. It's true that his death and resurrection reconcile God's creation. It's true that through him our sins are forgiven, but that's not why he comes. The answer is so straightforward it's hiding in plain sight. God comes to us in Jesus because God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; that is, from before the foundation of the world, God elected not to be God without us. Or as Jonathan Edwards liked to say, the Father is bent on his Son having a Bride and celebrating their love in the Spirit.

No matter what transpired in paradise, Jesus comes to be with us at Christmas because he was always going to come. The incarnation only unveils what was true from before the Big Bang. What we unwrap at Christmas isn't simply a rescue package, but an even deeper mystery. The mystery that the Nativity is an event that God has set on his calendar before God even made the creature called time. Even if there had been no need for a cross, there still would have been a creche because God has elected to be no other God than Emmanuel. God with us.

This what we affirm in the creed when we say that Christ is the one “by whom all things were made.” This what the first Christian sang in the hymn that Paul quotes in his letter to the Colossians, that Christ is “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. All things have been created through him and for him.”

He was before was was.

He is back behind yesterday.

Nothing ever happens for the first time— not even the LORD’s love for you.Therefore, he has always had more in mind for you than pardon.In other words— pay attention, this could not be more important:Jesus is not made for us.

We are made for him.

You were born for him.

You are the one with whom the triune God wants to share his life. At Christmas then, you are the gift God gives to himself. You— unimpressive, bewildered, petty, and yes sinful you— are the gift the LORD presents to himself. Before the stars were hung in the sky, before Adam fell or Israel's love failed, the Father’s deepest and abiding desire is welcome his Son’s Bride into the triune life.

As Oliver Sacks recalls the time of year, “it was around Christmas” when he first watched Jimmie G rapt in inexplicably sustained wonder and obedience.

Sacks writes:

“There in worship, Jimmie existed in perfect alignment of the present with the future, of the moment with the End. Seeing Jimmie in chapel before the loaf that is God’s body and the cup that is his blood, it opened my eyes to another realm to which the soul is called. Another realm to which the soul is called.”

Nothing ever happens for the first time.

The neurologist first witnessed his allegedly broken patient in perfect loving, awestruck communion with his Maker— week after week he saw them together— in 1975. Oliver Sacks saw more than Jimmie G, his empty memory filled by vibrant fellowship with God.

The doctor saw your destiny.One day you will be as whole as Jimmie G, lost in wonder, love, and praise.It’s too good to believe.

Just so—

It is good that you need no more proof than Luke’s news that Zechariah and Elizabeth were righteous according to the law and blameless before God.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers