Jason Micheli's Blog, page 27

November 5, 2024

Preach Christ, or Be Silent

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

As All Saints and Election Day converged on the calendar, I revisited some of the “political” writings from the church’s great cloud of witnesses.

In general, I think we are poor readers of scripture— preachers are no exception. We turn to the Bible in search of bias confirmation rather than sit with the scriptures to listen for a Word from the Lord. We do this in perhaps no more obvious ways than when it comes to our politics, turning to the Bible for principles and slogans to support positions upon which we had previously arrived.

In just this way, the doctrine of inspiration serves not our belief in the Holy Trinity and the Spirit’s gratuitous agency but functions as an aspect of our idolatry. The Bible becomes a supplemental resource for our a priori convictions rather than, as Barth says, a strange new world that is free to overturn our convictions and convert our ways of seeing reality.

Just so, we get the doctrine of inspiration backwards.

Among the many deleterious habits we have with scripture, Robert Jenson numbers this as our first false start with the scriptures.

He writes:

“The first disastrous false start that might even be regarded as sinful: we have gone at the matter of scriptural inspiration backward. We have begun with what we think we need from Scripture, and then have recruited the Spirit to assure us that our supposed needs are satisfied. But since the Spirit in question is God the Spirit, we must not in quite this fashion tell him what to do.

Surely we must rather start with the doctrine of the Spirit, with what we know of his character and work, and then ask to what ends this particular Spirit would have provided the church with the Scripture we in fact have, and how he would have gone about this provision. That is, our reflection needs to find its base in the doctrine Trinity; moreover, we should not be offended if a Spirit so identified disappoints some of our desires.

Let me—to get it over with—immediately instance a once prominent example of beginning in this backward way. We have wanted Scripture to be free of errors of any sort, and have invoked inspiration to assure ourselves that it satisfies this criterion. Now to be sure, most of us would indeed be easier in our minds if John and the Synoptic Gospels had compatible chronologies. Or if there were not the clash between the story told by Exodus and Numbers, of all Israel marching out of Egypt and through the wilderness, and the story suggested by historical-critical reconstruction, according to which it was in Canaan that various “Hebrew” tribes first came together as one nation. Or if—to instance the invariably adduced triviality—Leviticus did not seem to think that rabbits chew the cud. Or so on and on. Some of my seminary teachers were willing to perform rather spectacular mental gymnastics to show that all such phenomena could be explained away, that the tradents and authors of Scripture never just got it wrong. It was thought that if the Spirit had dictated the texts of the four Gospels, this would guarantee that the Gospels must agree in everything, since self-contradiction can hardly be attributed to the Spirit. And that if the Spirit dictated Leviticus there once must have been cud-chewing rabbits. And that if the Spirit dictated Exodus and Numbers their account of Israel’s origins must be the right one, despite what seems to be strong contrary evidence. And indeed, in abstract principle, a harmonization of the Gospels may eschatologically turn out to provide the best account; the story in Exodus and Numbers may similarly turn out to be accurate history; and there may once even have been cud-chewing animals reasonably to be called rabbits. Stranger reversals of established and well-justified scholarly opinion have happened.

But whatever may be the resolution of some of the problems we hoped to trump with inspiration, the order of the argument is in any case profoundly wrong.

We cannot recruit God to arrange what we think we need from Scripture.Not only should we instead think the other way around, and ask what specifically the Holy Spirit would do in the church with the writings he has actually provided—we might even ask what he intends with any errors found in them. In the latter connection, some of the Fathers had a theory that may not be so bizarre as it sounds at first: manifest errors and lacunae are there to trip up our penchant for exegetical simplicities.

Through the history of the church in all its aspects, the Spirit so urges and guides its life as to preserve the church from fatal error; just so and not otherwise, he guided the move from living proclamation to written text.

Nothing more special is required at this step of the Spirit’s gift of Scripture.We need no whispering in a writer’s mental ear of the words to be inscribed—no special suggestio verbi. We need only confidence that as the Spirit does not let the gates of hell altogether prevail in the history of the church, so he did not let error prevail when, for example, Ezekiel’s disciples and editors went to work to make a book of his prophecies as they remembered them—and indeed, as it seems, added a few items of their own.”

In other words, politics is very often the occasion for believers to act as though it is our task to continue the movement begun by the dead Jesus. We then approach the self-assigned kingdom task from our preferred right and left poles of the political spectrum, soliciting a stable text called the Bible to support us.

But the Bible is not the church’s book. It is the Spirit’s tool to do with us as he pleases.We should always, therefore, but especially at our times of annual idolatry, approach the scriptures with the self-aware humility of the prophet in the temple, “Woe to me, for I am a man of unclear lips.”

“Preach Christ, or be silent,” Jens insists.

That is, Jesus, the church, and Christ’s coming again are the literal meaning of every passage of scripture— and not our politics.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 4, 2024

The Mess is Ours

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Gretchen Purser is a wife, mom of three wonderful humans, and a person of deep and ever-evolving faith. She is a recovering evangelical, former political hack and a Republican refugee.

Gretchen built a 20 year career working for national republican campaigns, candidates, and committees and their adorable baby brother, the religious right. She’s “seen a lot of sh@t.” She’s passionate about music, and perhaps even more passionate about words.

Gretchen is host of the podcast “The Mess is Mine” which you should absolutely check out, here .Most importantly, Gretchen is a trusted friend (who may or may not owe me lunch by Tuesday night).Show NotesSummary

In this crossover episode, the hosts engage in a deep discussion about the current political climate in the United States, particularly focusing on the implications of the upcoming election. They explore themes of morality, character, and the responsibilities of Christians in the political sphere. The conversation highlights the polarization within society, the impact of Donald Trump on the Republican Party, and the challenges of navigating political discourse. The hosts also share their predictions for the election and reflect on the role of race and gender in politics, ultimately expressing hope for the future of American democracy.

Takeaways

The political landscape has shifted significantly under Trump.

Christians are called to consider their stance on poverty and politics.

Contempt in political discourse is prevalent on both sides.

Navigating conversations about politics is increasingly challenging.

The Republican Party is facing internal conflicts due to Trump's influence.

Character and morality in politics are crucial issues.

Polling may not accurately reflect the sentiments of the electorate.

Race and gender play significant roles in political perceptions.

The future of the Republican Party is uncertain post-Trump.

Hope remains for a more unified political discourse.

Sound Bites

"The character counts."

"It's a cult."

"I think she's going to win."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 3, 2024

God's Control+Alt+Delete

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Here is the latest in our discussions of Robert Jenson’s work on the Last Things.

This Monday, we will finish the final section of “The Saints”

You can join us live here at 7:00 EST.

In addition to the last few paragraphs of “The Saints” we will discuss the first portion of his essay on the The Great Transformation:

Jenson The Great Transformation862KB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

Summary

This conversation explores the themes of saints, eternity, and the nature of salvation as discussed by Robert Jensen. The participants delve into the implications of cosmic rectification, the relationship between judgment and justice, and the concept of heaven as a place of mutual discovery and individual identity. They challenge popular notions of heaven and emphasize the continuity of identity in the afterlife, while also addressing the restorative nature of divine justice. In this conversation, Marty Folsom and Jason Micheli explore the themes of righteousness, healing, judgment, grace, and the nature of salvation as presented in Christian theology. They discuss the implications of baptism, the urgency of living in Christ, and the possibility of exclusion from salvation, emphasizing God's love and grace throughout the discourse. The conversation highlights the importance of understanding these concepts in the context of everyday life and the church's mission.

Takeaways

Salvation is cosmic in scope and affects individual believers.

Rectification involves more than condemnation; it includes restoration.

Heaven is not a boring existence but a place of discovery.

Justice in heaven is restorative, fulfilling God's love.

Individual identity continues in eternity, shaped by our earthly lives.

The works we do nurture our eternal identity.

Fear of punishment is eliminated in heaven, allowing for true communion.

Heaven is a place where love removes fear and shame.

The nature of justice is intertwined with love and restoration.

Eternity involves a journey of becoming more fully ourselves. Righteousness in Christ is not limited to the cross.

Healing is an ongoing process, even in heaven.

Judgment should be viewed through the lens of grace.

Baptism is fundamentally about Christ's work, not our own.

Individualism can lead to a distorted view of faith.

The urgency of faith is rooted in the love of Christ.

Exclusion is possible, but not central to the gospel message.

The church's message should focus on inclusion and grace.

Understanding our identity in Christ is crucial for living faithfully.

God's love is unconditional, even in the face of human failure.

Sound Bites

"What will it mean for individual believers?"

"Heaven is that place where love removes fear."

"Heaven looks kind of like a waking up."

"Healing is still happening in heaven."

"Judgment no longer confines them."

"The threat of exclusion is made precisely to turn us away."

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 2, 2024

"All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone; All Saints is the celebration of those who are here."

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, why not?

Last year, during Advent, after the Christmas Pageant, one of the children in the cast came up to me in the fellowship hall.

“I have a question,” she said.

“What’s your question?”

“So…Jesus is alive?”

I nodded.

She thought about it for a moment. Clearly this hadn’t been her question.

“Well, if Jesus is alive, then how come we can’t see him?”

I knelt over and leaned in towards her and I whispered, like this was a secret too special to share.

“Actually,” I said, “you can see him; in fact, you did see him just last Sunday.”

“I did?”

I nodded.

“Yes, of course,” I said, “He was that bread on the table and the cup next to it. And all of us gathered around him in praise and petition. Jesus is alive and that’s the form— one of them, anyway— his body takes now.”

She nodded.

“Is that true,” she asked.

“What if it is true?” I replied, “What would it mean?”She thought for a beat.“I guess it means there isn’t much difference between there and here.”“What do you mean?”

“That there isn’t much difference between the there where God is and here where we are. Like, we don’t have to go very far to find love.”

Someone asked me this week, “Why do we do celebrate communion every Sunday?”

“Because John Wesley so instructed us,” I answered, “People accuse me of being insufficiently Methodist but I’m more Methodist than any of you.”

“Why did John Wesley instruct us to celebrate constant communion?”

“Because the Lord Jesus joins us at the table,” I said, “He is us at the table.”

The only body of the risen Christ to which the New Testament ever refers is not an entity in heaven but the Eucharist’s loaf and cup and the church assembled around them.

“You are the body of Jesus,” 1 Corinthians implores us to remember.

And the teaching there is a proposition and not trope. “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ?” the apostle Paul writes in the epistle, “The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.”

Again, we are “one body” in that we do something that can equivalently be described as “sharing in the body of Christ” and partaking of “the one bread.”

“The church is his body,” Ephesians says, “the fullness of him who fills all in all.”

Scripture demands nothing less than that you reconfigure your definition of what constitutes a body.The body of the risen Lord just is those believers who are baptized into him gathered around the loaf and the cup in praise and petition.The bread that we break and the cup that we bless is, as Martin Luther insisted, the gate of heaven.

Jesus is here.

You can see God.

And if this is the gate of heaven, if Jesus is present and available to us in the bread that we break and the cup which we bless, then likewise present and available to us are all those who have died in Christ.

Thus we pray, “And so, with your people on earth and all the company of heaven, we praise your name and join their unending hymn.”

This is the gate of heaven. The Lord Jesus is here. For you.But so are all his friends, Joseph and Liz and Gary and Jeanne and John…I know some of you are just going through the motions.

But imagine if it were true.

The journalist William Dalrymple wrote a travelogue of Christians in the Middle East called From the Holy Mountain, in which he tells an anecdote about the monks at St. Anthony’s Monastery in Middle Egypt.

St. Anthony was the Christian tradition’s first hermit.

William Dalrymple visited St. Anthony’s cave and met the monk, Father Dioscuros, who told Dalrymple a story about the body of Jesus and the communion of the saints:

There is a portion of the church which awaits the Kingdom not on earth but in heaven.

“You won’t believe this”—here Fr. Dioscuros lowered his voice to a whisper. “You won’t believe this, but we had some visitors from Europe two years ago—Christians, some sort of Protestants —who said they didn’t believe in the [communion of the saints]” The monk stroked his beard, wide-eyed with disbelief.“No,” he continued. “I’m not joking. I had to take the Protestants aside and explain that we believe that St Anthony and all the fathers and mothers have not died, that they live with us, continually protecting us and looking after us. When they are needed—when we go to them at the altar—they appear and sort out our problems.”

“Can the monks see them?”

“Who? Protestants?”

“No. The deceased, the saints. . . .”

“Well, take last week for instance. The Bedouin from the desert are always bringing their sick to us for healing. Normally it is something quite simple: we let them kiss an icon, give them an aspirin and send them on their way. But last week they brought us a small girl who was possessed by a demon. We took the girl into the church, and as it was time for vespers one of the fathers went off to ring the bell for prayers. When he saw this the devil inside the girl began to cry: ‘Don’t ring the bell! Please don’t ring the bell!’ We asked him why not. ‘Because,’ replied the devil, ‘when you ring the bell it’s not just the living monks who come into the church: all the holy souls of the saints join with you too, as well as great multitudes of angels and archangels. How can I remain in the church when that happens? I’m not staying in a place like that.’ At that moment the bell began to ring, the girl shrieked and the devil left her!”

Father Dioscuros clicked his fingers: “Just like that. So you see,” he said. “That proves it.”

“Proves what?”

“That just as the church fathers taught, the separated souls are hanging out around the altar because the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist—the post-resurrection body of Christ—are the closest they can get, until the general resurrection, to getting their bodies back.”

The fellowship of the baptized, because it is a communion of God’s eternally, life-giving Spirit, cannot be broken by time’s discontinuities, particularly not by death.

Thus, the church is a single, active communion across time of living believers and perished saints.

The communion of the saints is a communion across time; therefore, the communion of saints includes, even, your future self and, indeed, those saints not yet born.

Register the claim—At table, around loaf and cup, we commune with people not yet born.All Saints is not the remembrance of the dead.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are alive now only in Christ— and their availability to us.

All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have departed.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are here— and their power to minister to us.

This is the logical, sequential connection in the creed between the communion of saints and the forgiveness of sins, Maximus the Confessor teaches. The forgiveness of sins is not an item of the past but ongoing present labor. Contrary to Charles Wesley’s hymn, they are not at rest. We still sin against one another, and those who are now alive only in Christ are at work, in and with the Lord, to restore all things.

Scripture claims nothing less than this when it teaches that our faith directed at the Lord Jesus is simultaneously love directed at all the saints.The claims of scripture are astonishing if we can learn not to look the other way.All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are here.

Here— present with the Lord Jesus.

We are not alone.

You are not alone.

The saints are the light we cannot see.

Not only are we responsible for one another, there is a vaster number still who are responsible for us. As Jonathan Edwards writes, “The church in heaven and the church on earth are more one people, one city and one family, than generally is imagined.”

All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are yet here.

And though we may not always see or hear the saints, they know us infinitely better than we know ourselves exactly because their knowledge is a participation in the Lord’s knowledge of us.

When I was a boy, during the years when my father’s disease was at its nadir and he was seldom at home and my mother worked the night shift, I had a respite of sorts at my grandparents’s home.

I walked to their house from school, and they played with me and fed me and watched game shows with me and put me to bed.

My grandmother Theresa was an Italian immigrant and, like so many, a cook.

So far as I know, my grandmother did not attend Mass.

But she did have a portrait of Pope John Paul on the wall near the kitchen.

And the bed into which she tucked me had mounted above it a frighteningly large, baroque crucifix. And she prayed.

Theresa may not have been a churchgoer, but she was a praying woman.

Every night that she put me to bed, she would smooth my hair and pray the Our Father over me and then, as a sort of benediction, she would say, “We’re here. We’re here for you.”

To paraphrase Cormac McCarthy, if my grandmother's words were not, for me, the word of God, then God never spoke.

When I was in junior high, Theresa joined what Hebrews calls the “great cloud of witnesses.” Eighteen years ago, at my ordination service, I knelt before the bishop who stood beside the loaf and the cup on the altar as the body of believers gathered around us. And as the bishop laid hands on me to consecrate me to this bewildering, ill-fitting vocation, I suddenly had this apprehension— this vision and audition— of my grandmother Theresa.

And I heard her as clearly as I heard you all earlier profess the creed.

She said to me, “We’re here. We’re here for you.”

Those who have died in the Lord are not departed.

Not only are they not gone, the Lord is not done with them.

The verse in the Book of Hebrews that immediately precedes the description of the great cloud of witnesses says, “Only together with us will the saints be made perfect.”

It’s astonishing how we read right past the astonishing claims of scripture.The saints are not gone but neither are the saints yet fully sanctified.Which is also to say, the dead who have died in the Lord are not merely alive.They are more alive than we are.The same passage in Corinthians:

When Paul gives the church instructions for celebrating the Eucharist, how does he introduce the sacrament? After all, Saul was not present at the last supper. Paul doesn’t say to the Corinthians, “As I read in the Gospel of Matthew.” Paul did not have the New Testament. Nor does Paul write, “This is what the other apostles have shared with me.” No, Paul testifies, “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you…”

Paul learned the Eucharist, so to speak, from Saint Jesus.All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are yet here.

We are not alone.

There is more to reality than what we can make out.

There is a reality that is deeper than the darkness we can see.In an essay entitled “What If It Were True?” Robert Jenson writes:

“There is a reason for our skittishness with the gospel’s truth claims…So soon as we pose the question, “What indeed if it were true?” about any ordinary proposition of the faith, consequences begin to show themselves that go beyond anything we dare to believe…The most Sunday-school- platitudinous of Christian claims say, ‘Jesus loves me’ contains cognitive explosives we fear will indeed blow our minds…

Let me give a prolegomenal instance. We sometimes join our daughter’s family for the main Sunday Eucharist at New York’s cathedral of St. John the Divine. Besides seeing our family, we go there because what happens of a Sunday morning often makes an occasion within which we can credit biblical stuff that stumps us in other contexts. For our time’s sake I will stick to what the cathedral’s organist, the amazing Dorothy Pappadokos, does. While her French-style improvisations are shaking the stones of the building, and my stony heart, when climax upon climax each improbably eclipses its predecessor, I am able to sustain the notion that all God’s various holy ones are gathered there with us, that in fact we are praising God, as the liturgy of my church has it, “with angels and archangels and all the company of heaven,” that if only we could see what is actually there, we would see the mighty thrones and dominions and Mary and Paul and Olaf and my father-in-law and so forth around us in the cavernous spaces.

But sitting in front of my computer to write for publication, I chicken out, and begin looking for ways to pare down the proposition [according to] modernity’s prejudices…And of course it is a mind-bending exercise to consider in what mode dead believers make one living company with living ones, but do they or don’t they? Is Papa Rockne there for our Eucharist or is he not?” If we say yes, then we must repent of all our assumptions about what constitutes the “real world.”

War in Israel, fear amongst Jews, grieving in Gaza, despair in Ukraine, dysfunction in Washington, a lethargic pace of change in the UMC, a burning planet, your breaking marriage, the Big Lie— nevertheless; there is a reality afoot that is deeper than the darkness we can perceive.

There is light we cannot see.

There is a reality afoot that is deeper than the darkness we can see.

Jesus is Lord.

And, as surely as I heard my grandmother, the Lord Jesus and all the company of heaven are speaking to us, “We’re here. We’re all here.”

Just last Sunday, a friend of mine, a Christian who lives in Northern Israel, emailed me to say, “My mother and father died ten years ago. Yesterday they appeared to me in my dream and they told me to tell you that they’re praying for you. They said your name, Jason. How on earth do they know you unless it is all true?”

She underlined that last clause.

Once you ask Jenson’s question, “What if it were true?” once you give Christians permission for their Christianity to be weird, you hear stories like this all the time.

Stories like this story a former parishioner sent me:

“Almost thirty years ago, our son was a teenager. He was troubled. We were able to get him registered in a prep school in New England. But during orientation, he ran away into the streets of Portland and was missing for days. Both my wife and I were worried sick had been praying that he would be okay. On the third day, I had been listening to religious music in my car, and there in my vehicle, in the dark and in silence, I heard my son’s voice say— I heard my future son’s self say, “Everything is going to be ok.” Those six little words from beyond what we can see pulled us through an awful time.”

Nothing that is possible can save us.

Once you ask Jenson’s question, “What if it were true?” once you allow Christianity to be weird, you can discover a reason for actual hope.

In that same essay, Jenson writes:

“It makes a difference. What do we think we inhabit? A machine of some sort? If so, we are victims of an illusion. What we really inhabit is rather a drama, the drama of Israel’s God…

It makes a difference. I do not know if our culture can be rescued from the superstition that recognizes only sub-personal forces as finally real.

If it cannot be rescued from that illusion, we will, for but one matter, continue so to present reality to students in the schools as to persuade them of their own meaninglessness and of the inconsequence of all their actions. I acknowledge that left to myself, I would despair. But since we are not left to ourselves. who knows? The church, anyway, must fight in all the ways she can against the realization of the Clockwork Orange also in her own life.”

All Saints is a way we fight against the Clockwork Orange. All Saints is a way we fight against the resignation that only what we can see is real. Allow me to throw a punch in the fight.

In the Book of Malachi, Jesus speaks to the prophet, telling him to exhort God’s people to remember the commandments given to Moses. But— Jesus cautions Malachi— even if the people do keep the law, I am sending Elijah to convert the hearts of generations.

Elijah is but one of the saints.

In other words— and, again, it’s weird— Jesus dispatches the saints from the Last Future back through time to turn hearts towards him.

Which means nothing less than…

My grandmother did not say, “We’re here. We’re here for you,” merely to steady me in the midst of a turbulent childhood.Rather, Saint Theresa gave those words to my grandmother so that I would apprehend them at my ordination.Still further, Saint Theresa gave those words to my grandmother to speak over me as a boy; so that, today I could relay them to you and with them, through them, you would know that everything is going to be okay.

No matter how dark the world may appear, the light is winning.

What if it were true?

For starters, there would be no reason you would not rush. Run straightaway to the table. With God, there is no here and there. There is only ever here. Therefore, you don’t have to go very far to find love.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 1, 2024

The Saints are Not Our Way to Christ; Christ is Our Way to Them

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

On the Christian liturgical calendar, today is All Saints.

Inviting worshippers to the Eucharistic table, I’ve sometimes noted how the church’s altar only appears to be in the shape of a semi-circle. When we gather around the loaf and the cup, there is another unseen half of the ring where saints from the cloud of witnesses join us at table. As we pray in the Great Thanksgiving, “And so, with your people on earth and all the company of heaven, we praise your name and join their unending hymn…”

Just so, the theologian Robert Jenson— a Protestant— stipulates two rules for a theology of the saints:

The saints are not our way to Christ; Christ is our way to them.

Our communion with the departed saints is not substantially different from our fellowship with the living saints.

With All Saints immediately subsequent to Reformation Day, Jenson’s rules invite a reappraisal of one of the questions which allegedly divide Christ’s Body between Catholic and Protestant.

Can the living do more than remember the dead?Can the living solicit the prayers of the dead?Can Christians do more than confess belief in the communion of saints?Can we ask them to pray for us?

As any pastor knows, these questions are pastoral as much as they are theological or scriptural. Can the living speak to their loved ones after they are gone (they will regardless of how you answer)? Will the presence of loved ones abide even though they are dead (they will no matter how you respond)?

The door from this life to the life to come— it isn’t just narrow as Jesus says in the Sermon on the Mount. Every year All Saints forces us to remember that Jesus Christ has made all the world a thin place between the living and the dead. Saints are not simply the dead in Christ. Saints, the New Testament makes clear, are any believers who have been baptized into Christ. It’s a distinction that applies to the living as much as to the dead.

To believe in the communion of the saints, therefore, is to believe that Jesus Christ has forged a bond between the baptized that stretches not only throughout the globe but across time.

The door is more than narrow. It’s thin. It’s so slight it’s not even like a door or a gate at all anymore. It’s more like a veil because Jesus Christ has bridged the greatest barrier that divides human beings, death. Death— not culture or color, not language or class, not political parties— is the divide that splits every human being into one of two categories, living or dead. On All Saints, we remember that the Body of Christ is the most inclusive community imaginable upon the earth not only because it’s for sinners (which means you’re included) but also because it’s a community comprised of the living and those who are now alive, for the time being, only in Christ.

When the church baptizes someone, we baptize them into Christ. By water and the Spirit, the Father gifts to every believer an unevictable place in the Son. And so death does not alter in any way our fundamental location. We’re all already in him. This is why, from the very beginning, Christians have used the word “veil” to describe death, something so thin you can nearly see through it.

Baptism is a bond that cannot be broken by time or death because it’s an incorporation into the Living Christ.Thus, the dead in Christ don’t disappear.Therefore, our fellowship with the departed is not altogether different from our fellowship with the living.That’s what we mean when we say in the Creed, “I believe in the communion of saints…” We’re saying, “I believe in the friendship between the living and the dead in Christ.”

So, as Robert Jenson asserts, we can pray and ask the departed saints to pray for us.

So, as Robert Jenson asserts, we can pray and ask the departed saints to pray for us.Not in the sense of praying to them, not in the sense of giving them our worship and devotion, but if we believe in the communion of saints, living and dead, then asking the departed saints for their prayers is no different than you asking me to pray for you. Again, it is not, as Protestants so often caricature, that the saints are our way to Jesus Christ. He is our way to them.

Because we (living and dead) are all friends in Jesus Christ we can talk to and pray for one another.I was in Texas last fall speaking at a conference.

Passing through Denton on the way to Oklahoma City where I preached that Sunday, I suddenly felt compelled to reach out to a childhood friend, Gary, who lives in the area. I haven’t seen him or spoken to him since my wedding day. I don’t even have a phone number or email for him. I messaged him on Facebook.

“You suddenly popped into my mind and I thought I’d reach out and say hello.”

The rolling text bubble appeared instantly on my phone.

“Mom’s been in hospice for a while now,” he typed back, “She died only a minute ago.”

The universe is not large enough to accommodate coincidences of that kind.

It strikes me as far more reasonable to profess, “I believe…in the communion of saints…” And, so believing, to ask Gary’s Mom, from time to time, to pray for me. Lord knows— she now knows too— I need it.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 31, 2024

Politics Tempts Us to Play God; What Sets the Saints Apart is their Readiness to Let God be God

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

What sets the saints apart is their unusual readiness to let God be God.

As Stanley Hauerwas says, this is a politics.

As All Saints and Election Day have approached on the calendar, I have been revisiting some of the “political” writings passed down to us from the cloud of witnesses.

The creed is perhaps the church’s most ubiquitous undercover political document.

Had Jesus not hijacked me away from my well-laid, culturally-approved plans, perhaps I would not be in the position to profess the Apostles’s Creed every Sunday. In so doing, I have often chuckled from my perch up front that the third article requires us to believe in a creature as compromised as Christ’s bride, “the church.”

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and life everlasting.”

Lately, however, the creed has struck me not for the belief it beggars but for the items it omits altogether. With the creed, the primal church posited the dogma of the faith; quite simply, the content of its three articles demarcate the convictions which constitute a Christian.

As Robert Jenson says, one who cannot describe these events or trust their veracity is no Christian. Needless to say, there is a great deal to the cruciform life not detailed in the church’s dogma. As a promise about the future where Jesus now lives, the gospel obviously bears implications that are as diverse and myriad as those who hear it in the present.

On what the gospel means for its lived witness, the creed is necessarily silent. All the faith requires to be reckoned faithful is affirmation of the creed’s brief tripartite summation, “I believe…”The creed’s use in the sacrament of baptism underscores its function in just this way. This is remarkable! We live— at least, we Christians in America— at a time when many Christians depart from their churches or condemn the churches of others based on alleged articles of faith conspicuously absent from the creed— the atonement, the inspiration of scripture, and sexuality to name but a few. Likewise, Election Day 2024 appears to be the lectionary many preachers and churches have been heeding of late. Many congregations in my area, I've noted, have been offering programs like “40 Days of Prayer for the Election” while others will be hosting candlelit vigils next Monday evening or “Election Day Communion.”

Though all mainline Christians vote in a rough 50/50 Red-Blue split, fellow clergy recently looked at me with both pity and reproach when I offered, offhand, that my congregation was in no way homogenous when it comes to the circles they will fill on their ballots Tuesday.

The clergy’s eyes betrayed an assumed dogma that, once again, does not appear in the creed.

This is not to say that I lack political convictions or that I do not have strong opinions. Nevertheless, the creed rudely ignores both my convictions and my opinions.

However right or wrong history may judge me for my political convictions or my opinions on current events, the creed cares to measure neither.Instead of my partisan commitments or positions, the creed insists I affirm a claim that appears absurdly ethereal in comparison to the everyday, earthly priorities of politics:

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

In an All Saints sermon from 2009, Rowan Williams reflects on the saints named by Hebrews 11, writing:

“Without us,” says the writer, “they will not be made perfect.” This is a truly extraordinary claim. We’ve heard about the heroes of the Old Testament, the Judges and the Prophets, those who have suffered atrociously for their faith, those who have performed stunning miracles, “And yet the writer to the Hebrews says baldly without us they will not be made perfect.” Think of that in our own terms. Without us, Francis of Assisi will not be made perfect, without us St John of the Cross will not be made perfect, without us Mother Theresa will not be made perfect…The holiest, the most whole of God's children, reach that wholeness only in communion with us.

Williams begins his All Saints sermon with a passage from Etty Hillesum, a young Jewish writer who died in Auschwitz. On the train to the death camps, she scribbled her final thoughts:

"Someone has to take responsibility for God in this situation. That is, someone has to behave as if God were real. Someone has to make God credible by the way that they meet life and death.”

Someone has to behave as if God were real.

The saints, living and dead, are those who make belief credible by living in a manner that makes sense if the living God revealed in the scriptures is not real. And this is the manner in which the third article of the creed is a thoroughly political confession, for what sets the saints apart, really, is their unusual readiness to let God be God.

Make no mistake, as Stanley Hauerwas says, this is a politics.Nor is this a politics of passivity or quietism, for many of the lives the church recalls in the creed are those who died as martyrs.

I’m old enough to have noticed that the phrase “the most important election of our lifetime” is a quadrennial invocation. If many believers are to be believed, election season in America is a time when a less than Almighty God apparently needs a great deal from us, not the least to save America or protect democracy. In other words, election season is a time which tempts many Americans to play God, to try to fix ourselves and others, to try to get a handle on what is happening to us and around us.

Politics tempts us to try to play God. Politics tempts us to do God’s work for him—only better. And when we think the End is up to us, we can justify all sorts of means.By contrast— What sets the saints apart is their unusual readiness to let God be God.In Etty Hillesum’s terms, much of the religious rhetoric in our politics is self-refuting, belying a God who is real.

As Chris E.W. Green says, the communion of saints reminds us that what is needed in our world is to leave room, to hold space, to wait on the Lord. And that is what the saints do—for us. Exactly so, they not only help us see God more clearly, they also make God look good and make the faith more believable.

With their humble, comparatively simple, often anonymous lives, the saints remind us that time is not one damn thing after the other and that what we call the world is actually creation. The saints stand rudely in the church’s dogma as a reminder that God is not only the author of the story we inhabit but an actor within it; therefore, we can attempt to live in a manner that makes this story intelligible— even at the risk of “losing.” We can, then, let God be God.

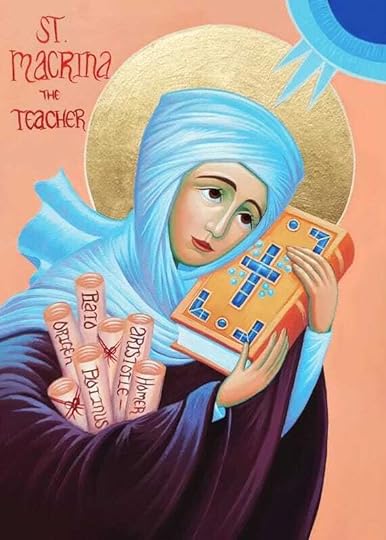

Put another way, the creed ventures the claim that Kamala Harris and Donald Trump simply aren’t as interesting as Francis of Assisi or Macrina the Younger.

To quote from Rowan Williams’s sermon again:

That is, God deals with us not by agreeing to the be totem of our political aspirations or the balm against our political fears. God deals with us by calling forth lives that make it possible to believe he’s got the whole world in his hands.“Witnesses establish the truth by giving evidence. It really is as simple as that. When we celebrate the Saints, we celebrate those who have given evidence, who have made God believable by how they have lived and how they have died. The saints are the people who recognise that arguments will finally not win the day. God does not make himself credible by argument. God does not respond to our doubts, our intellectual querying, our uncertainty, by delivering from Heaven a neatly annotated list of logical propositions with which we cannot disagree… God deals with us by our life and a death, by Jesus. And God continues to deal with us by lives and deaths that make him credible, that make Jesus tangible here and now.

And those hands bear holes.

Just so—

The communion of saints is not only a political declaration, it is gospel.

It is a promise of pastoral comfort in a world beset by anxieties.

The saints remind us what is possible in a frightening world as a member of the totus Christus. Long after another of the most important elections in our lifetime recedes into history, the communion of saints is the good news that the Father will remember what his Son’s Bride in the Spirit has remembered, the lives of those who, in their ordinary and imperfect ways, made God real.

In a world of cynicism, skepticism, and both-sidesism, Love alone is credible, says Hans Urs Von Balthasar. But the love that is credible alone is the Love made tangible in the lives kept eternally in the creed’s third article:

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 30, 2024

How to Die in Paradise

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

You can boil the whole promise of Jesus down to one word, “You.”

Luke 23:43

St. Dysmas Lutheran Church: South Dakota State Penitentiary, Sioux Falls, SD

Here is a sermon by my friend Dr. Ken Sundet Jones of Grand View University. Ken is a part of the Iowa Preachers Project with me. FYI: St. Dysmas is the thief on the cross to whom the Lord promised paradise on Good Friday.

Not many sermons elicit immediate requests for baptism. This one resulted in 8 inmates asking to be baptized. And an absolution for the books.

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father and our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

Amen.

1. Poor old St. Dysmas. He got a great promise from Jesus and then one Dysmas recognized as the messiah with the power to bestow a place in paradise breathes his last. Jesus is dead, and Dysmas has the same fate ahead of him.

a. Now Dysmas watches as people scramble at his feet. Messengers are sent back and forth to the Roman governor of this occupied territory. Finally, with hardly any time before sunset and the Jewish law’s demand for an end to all activity, Dysmas watches as Jesus’ hands and feet are released from their spikes and his body is lowered from the cross, wrapped in hastily acquired graveclothes, and carried off somewhere to be buried.

b. Now, in the twilight, our beloved thief has time to think about what Jesus just promised him and what it means for him in the short time left of his life.

c. Saint Dysmas hangs between the two most significant moments of his life.

2. In 1532, John the Steadfast of electoral Saxony died. His brother Frederick the Wise had been Martin Luther’s prince for the first eight years of the Reformation. When Frederick died in 1525, John took over as the prince elector.

a. It was John, who traveled to the city of Augsburg to attend the diet, the meeting of all the representatives of the Holy Roman Empire.

b. John was present when Philip Melanchthon and the others presented what would become known as the Augsburg Confession before Emperor Charles V. John is known by the name of steadfast, because he literally stood fast before the emperor, the powers that be, and all the arrayed representatives of the church in Rome.

c. Now in 1532, Prince John was dead, and Martin Luther was called upon to preach at his funeral.

d. In Luther’s funeral sermon for John, he said that John had died two deaths. Luther argued that this death that everyone seemed to be so upset over was just a little death. It was no big deal.

e. That was so because the prince had died a big death two years before in Augsburg. John’s big death occurred when he risked his life to defend the faith, the preaching, and the teaching of Luther and his fellow reformers, not just in Wittenberg, but in so many and varied places in the empire. Prince John risked it all.

f. Up until that point, John’s life as an important political figure in Europe, and in his territory was a given, in Augsburg, something happened. Everything changed. The prince showed himself to be one fully dependent on the good news of Jesus Christ crucified and risen.

g. That was why, Luther said, that this present death was nothing to weep and wail over. What those gathered for the funeral should do instead of sobbing and wringing their hands was to hand John over with thanks for the gift he had been to the church and its proclamation.

3. Saint Dysmas, too, died two deaths. His second death happened when he, like Jesus, finally breathed his last breath, and they took his body down from his cross to be buried in some unknown plot to be forgotten forever.

a. Dysmas’s first death, however, according to the terms laid out in Luther’s funeral sermon for his prince, happened in that conversation we’ve been talking about all weekend, when he asked Jesus to remember him in paradise.

b. That moment was a hinge, an axial point, a place that could be pointed to that had a distinct before and after. With Jesus’s words that today he would be with him in paradise, it wasn’t possible that anything could ever be the same.

c. Even in the dark of that sabbath night, St. Dysmas

knew he was changed. As he hung there, with his breathing becoming ever more difficult through the night, and through the long hours of the next day, St. Dysmas had time to consider what had changed. Jesus had declared that paradise was his. How was St. Dysmas to die in this new paradise?

4. My friend Jason Micheli reminded me as we were talking about St. Dysmas of the story of a French monk, who saw himself as a modern day St. Dysmas:

a. Father Christian de Cherge was a French Catholic monk and the prior in charge of the Abbey of Our Lady of Atlas in Algeria. He was beatified four years ago.

b. Christian De Cherge had served in Algeria as an officer in the French army during the Algerian War for independence and, shortly after his ordination to the priesthood in 1964, he returned to the country to minister from the little abbey to the poor, mostly Muslim community of Tibhirine.

c. De Cherge’s father regarded his son’s decision to take monastic vows with unmeasured disappointment. After all, his son was brilliant. He’d graduated at the top of his class and his future could have been bright, pursuing any career he chose.

d. Instead de Cherge felt called. Along with his fellow monks, de Cherge toiled in relative obscurity for three decades, winning the trust of the poor and befriending leaders in the local Islamic government.

e. When Islamic radicalism spread to Algeria in the early 1990’s, to the consternation of their superiors in Rome and to the anger of their families in Paris, de Cherge and his fellow monks refused to leave their monastery, because they refused to stop serving the community’s poor. They knew that meeting a violent end might simply be the consequence of faithfulness to the Lord who had called them to such a place.

f. On January 1, 1994, de Cherge, had a vision of his own impending murder. And that’s exactly what happened. He and seven of his brothers from the abbey were kidnapped and eventually beheaded by terrorists calling themselves the Armed Islamic Group.

g. Anticipating his own murder, Christian de Cherge wrote a kind of last will and testament and sent it to his family to be read after his death. This is what de Cherge wrote:

h. “If it should happen one day — and it could be today —

that I become a victim of the terrorism which now seems ready to engulf all the foreigners living in Algeria, I would like my community, my Church and my family to remember that my life was not taken. My life was to God. Indeed this ending had its beginning in my baptism.

I ask them to accept the fact that our Lord was not a stranger to this brutal departure.

i. “

I would ask the me to pray for me: for how could I be found worthy of such an offering?

I ask them to associate this death with so many other equally violent ones which are forgotten through indifference or anonymity.

My life has no more value than any other. Nor any less value.

j. “In any case, it has not the innocence of childhood.

I have lived long enough to now that I am an accomplice in the evil which seems to prevail so terribly in the world, even in the evil which might blindly strike me down.

k. “

I should like, when the time comes, to have a moment of spiritual clarity which would allow me to beg forgiveness of God and of my fellow human beings, and at the same time forgive with all my heart the one who would strike me down.

l. “

I could not desire such a death.It seems to me important to state this.

Obviously, my death will appear to confirm those who hastily judged me naive or idealistic: ‘Let him tell us now what he thinks of his ideals!’

But these persons should know that finally my most avid curiosity will be set free.

m.“

This is what I shall be able to do, God willing: immerse my gaze in that of the Father to contemplate with him His children of Islam just as He sees them, all shining with the glory of Christ, the fruit of His Passion, filled with the Gift of the Spirit whose secret joy will always be to establish communion and restore the likeness, playing with the differences.

n. “

For this life lost, totally mine and totally theirs, I thank God, who seems to have willed it entirely for the sake of that joy in everything and in spite of everything. In this thank you, which is said for everything in my life from now on, I certainly include you, friends of yesterday and today, and you, my friends of this place, along with my mother and father, my sisters and brothers and their families — you are the hundredfold granted as was promised!”

o. Finally, remarkably, at the end of his letter Christian de

Cherge addressed his executioner with a word of mercy and forgiveness:

p. “And also you, my last-minute friend, who will not have known what you were doing:

Yes, I want this thank you and this Adieu to be a "God bless" for you, too, because in God's face I see yours.

May we meet again as happy thieves in Paradise, if it please God, the Father of us both. Amen! Inshallah!

5. Christian de Cherge’s letter to his family, the way he regarded his life as no longer his own, and his final absolution of the man who beheaded him give us an inkling of what may have occurred to St. Dysmas i his last hours on the cross.

a. Indeed, they also call us to consider what our lives mean in between our two deaths, between the moment our Lord claims us, and gives us new life in baptism, and the moment we finally lay down our heads and breathe our last.

b. Our first death, as it was for St. Dysmas, is a release. In Jesus’s claim on us, he frees us from captivity to ourselves.

c. Some days I long to be rid of my attachment to my holy self-regard, my self-sanctified self-continuity project. It’s such a long hard slog to be Ken Jones. I get so tired of having to maintain a façade of having it all together, of being in control, of having any idea at all of what I’m doing. I float along blithely, ignoring the consequences of my actions. I act as though every day will be followed by another and another and another where I will do as I please.

d. And yet in my baptism on July 31, 1961, at First Lutheran Church in Newell, South Dakota, Jesus declared I would be with him in paradise. Everything that’s happened in my life since that point, in spite of my delusions and imaginings to the contrary, has been the life that my Lord gave me.

e. Do you suppose that St. Dysmas at sabbath day after Jesus died felt released? Did he feel, like our French monk, that his life, as little was left of it, and as painful as it was, was no longer his own? Did he die in the paradise Jesus had granted him knowing that his existence was one small drop of water in the ocean of God’s eternal grace and mercy? Did St. Dysmas look down from the cross and speak an absolution to the Roman soldiers, who nailed him to the wood, and raised him up to die a humiliating death?

6. Is it possible that St. Dysmas had that kind of change of heart as a result of Jesus’s promise to him? Is it possible for me to be that kind of changed person too? Is it possible that God can wreak that kind of change in you?

a. I know well how the world regards inmates of the South Dakota State penitentiary: criminals, murderers, thieves, addicts, molesters, rapists. The world as a whole and the system under which you live on the hill have no ability to see you as anything more more than a mass of nothing in khaki scrubs with the word inmate written down your legs.

b. But I know the Jesus who spoke to St. Dysmas. I know the Lord, who claims the least, the last, the lost, the leper. I know the God who speaks a word into the midst of chaotic nothing at the beginning, and creates new life.

c. And I have seen evidence every time I’ve been blessed to enter this hallowed space of Hope Chapel and had the privilege of being in the presence of my beloved brothers in Christ in this place.

d. Pastor Jeff, former inmate #39016, is a cleaned up, prettified example that the world sees as a far cry from what they regard you as. But Jeff is no example whatsoever (and he’d probably say that we should think of him instead is a dire warning). I think we could regard your pastor as a lens through which we can access how God sees you.

e. Jeff Backer is St. Dysmas. I am St. Dysmas. You are St. Dysmas. All of us are thieves who have stolen the very grace of God and discovered that Jesus wasn’t ever going to let us steal it. He was doling it out freely and unreservedly to the undeserving, to the godless, to the reprobate, to me and you.

f. All this he does on the cross as he declares the gates wide open, so that you can die in paradise with him, and live in his grace and mercy forever. This day. Today. And every day after. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 28, 2024

And finally . . . ‘The Best High-Protein Diet’

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Seriously, do it!

Preaching on the final chapters of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, I have been reflecting on scripture and the church’s doctrine of inspiration. For instance, in chapter 15 Paul cites Psalm 69 but makes Jesus the speaker of it; that is, Mary’s boy is the one who speaks in what would have been his scriptures.

And then in Romans 16 Paul commends Phoebe, the woman to whom he has entrusted the letter’s delivery and, presumably, its interpretation. What does it mean to say that scripture’s divine inspiration extends to those, like you and me, who have been entrusted with its interpretation and proclamation?

With scripture on my mind, I thought I would share this old piece I stumbled upon from the Expository Times by my muse and mentor (and subscriber!) Fleming Rutledge:

A friend writes from another city that a new pastor has settled into the pulpit of his parish church. The congregation had been suffering from a dearth of preaching during a difficult interim period. ‘The parish is more settled now,’ he writes, ‘but, as much as I hate to say it, I am a little disappointed. It is so hard to keep faith fed and there is a lack of passion which sometimes feels like just going through the motions.’

‘To keep faith fed.’

This is a striking phrase. A wise biblical interpreter whom I know speaks of the ‘vitamins’ and ‘protein’ that the people of God require for the long haul.

The Psalmist writes:

“O taste and see that the Lord is good! Happy are they who take refuge in him! O fear the Lord, you his saints, for those who fear him have no want! The young lions suffer want and hunger; but those who seek the Lord lack no good thing. (Psalm 34)”

And Amos memorably writes:

“Behold, the days come, says the Lord God, that Iwill send a famine in the land, not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the Lord’ (Amos 8:11).”

If preachers of the Gospel can envision their flocks as people who are malnourished, even starving, for lack of the invigorating Word, that perceived lack might cause some stirrings of passion from the pulpit. Maybe we have been convinced too easily that people want only sound-bites today. Perhaps we have lacked confidence in the message that has been entrusted to us. We might recall the ringing declaration of the apostle Paul who teaches us that the message itself is its own guarantor (‘faith comes from the message [akoê]’ – Rom 10:17). To those who are being saved, he writes, the message of the crucified One is the power of God (1 Cor 1:18).

I don’t know of any preaching technique or homiletical theory that can compare with the Biblical announcement that ‘The Lord utters his voice . . . he that executes his word is powerful’ (Joel 2:11). ‘I have spoken [says the Lord], and I will bring it to pass; I have purposed, and I will perform it’ (Isa 46:11). ‘He who calls you is faithful, and he will do it’ (1 Thess 5:24). We are not offering religious thoughts or spiritual recipes; the Christian sermon is the performative power of God.

I don’t know of any preaching technique or homiletical theory that can compare with the Biblical announcement that “The Lord utters his voice.”

When I was in Edinburgh last spring, I was attracted to a church tucked back on a side street. It had a little home-made sign out front for Eastertide that said ‘Jesus is alive!’ That little sign drew me in because it proclaimed a living God. The preacher that day was a layman, dressed simply in a shirt and bow-tie with no jacket. Toward the end of the sermon he told a story that I had heard before – it is one of those stories that has been recycled many times – but the simple, unaffected way that he told it combined with his own very obvious sincerity struck me to the heart.

The story concerned a situation in which an actor was performing various readings before an audience. He asked for requests and an elderly clergyman asked for the 23rd Psalm, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’. The actor agreed to recite it, but asked that the pastor making the request recite it also. When the actor finished his recitation with many oratorical flourishes the audience burst into applause. Then the elderly pastor rose and recited the Psalm from memory in a quavering voice. When he finished, the audience sat in awed silence. The actor said, ‘Sir, I knew the Psalm; but you – you know the Shepherd’.

So this is an appeal for preachers who know the Shepherd, preachers who know both the Scriptures and the power of God, preachers who understand that their congregations are malnourished and need to receive a Word of life given from the mouth of the Lord. ‘What father among you, if his son asks for a fish, will instead of a fish give him a serpent; or if he asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion?’ (Luke 11:11).

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 27, 2024

In Persona Verbi

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Romans 15.1-13

Ten years ago this winter, I took twelve months of medical leave for stage-serious cancer. In the interim, not wanting to be a distraction in my own congregation, I tried to worship with other congregations near and far from our home. I was not prepared— not at all— for how difficult it was to find a church where either the preacher or the people appeared to expect God to speak. In every case, they treated the Bible like an artifact instead of the living Word of God.

Eventually, I gave up my search and stayed home on Sundays.

Because, why would I not?

Paul himself says that if the Word is not alive, then we are all wasting our time.In the Gospel of Matthew, after the Pharisees attempt to entrap Jesus with a question about paying taxes to Caesar, the Sadducees sidle up to him with an equally loaded question. Citing the scriptures, they posit a woman who has been widowed seven times. “You tell us, Jesus. In the resurrection, whose wife will she be? Which of those guys will be her husband?”

Impatient with their unserious question, the Lord replies, “Is not this the reason you are wrong, that you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God?”

Neither the scriptures nor the power of God.

The link between the two is the key.The power of God is manifest in his word.To reiterate this very point, Jesus directs them back to the Bible. “Have you not read what was said to you by God in the scripture?” Jesus asks them— and note the change in tense, “There the Lord says, “I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.””

The Bible is not an artifact.The scriptures are not simply the record of what God said.The scriptures are the means by which God says.William Stringfellow was a lawyer and social activist in the middle of the last century. After graduating from Harvard law school, Stringfellow moved into Harlem and began a career representing victimized tenants. Stringfellow believed it was his baptismal vocation to advocate against the principalities and powers. An Episcopalian, Stringfellow was a brilliant lay theologian who fit into neither the liberal nor the conservative wings of the church precisely because he challenged the status quo not on progressive political grounds but according to the Word of God. Stringfellow’s Civil Rights advocacy, for example, put him at odds with conservative believers, but his high view of scripture often discomfited his fellow activists, who preferred to regard the Bible as an curio.

In his book Count It All Joy, Stringfellow recalls one such instance of his esteem for the scriptures embarrassing his fellow believers.

He writes:

“A few years ago, serving on a commission of the Episcopal Church charged with articulating the scope of the total ministry of the Church in modern society. The commission included a few laity and the rest were professional theologians, ecclesiastical authorities and clergy.

Toward the end of the first meeting, some of those present proposed that it might be an edifying discipline for the group, in its future sessions, to undertake some concentrated study of the Bible. It was suggested that constant recourse to the Bible is as characteristic and significant a practice in the Christian life as the regular celebration of the Eucharist, which was a daily observance of this commission.

Perhaps, it was suggested, Bible study would enlighten the deliberations of the commission. The proposal was rejected on the grounds, as one Bishop put it, that “most of us have been to seminary and know what the Bible says; the problem now is to apply it to today’s world.”

The bishop’s view was seconded (with undue enthusiasm, I thought at the time) by the Dean of one of the Episcopal seminaries as well as by the clergy from national headquarters who had, they explained, a program to design and administer.

The point in mentioning the incident is that the notion implied in the decision not to engage in Bible study is that the Gospel, in its Biblical embodiment, is a static body of knowledge which, once systematically organized, taught, and learned, is thereafter used only ceremonially, sentimentally, and nostalgically.”

A static body of knowledge.

You know neither the scriptures nor the power of God…there the Lord says.

It was his encounter with these final chapters of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans that converted the pagan Augustine of Hippo to the faith of his Christian mother, Monica. In the year 386 AD, Augustine was teaching rhetoric in Milan. In a garden, Augustine heard a voice— the voice of a child, maybe the voice of God, summoning him, “Take and read. Take. And read.”

The voice resisted dismissal. Finally, Augustine located a Bible. He picked it up. He opened it at random to Romans. And he read the first passage he saw. As Augustine recounts in his Confessions:

“I read in silence the first paragraph that my eyes fell upon from the Apostle’s letter to the Romans…Immediately, the light of freedom poured into my heart and all the shadows of doubt were scattered.”

For Augustine—

The scriptures were not an artifact.

The scriptures were the power of God.

They made Augustine Saint Augustine.

Paul concludes his long discussion of the partisan dispute which divides the church at Rome by returning to the initial command with which he began. “Now we who are strong,” Paul writes in verse one, “ought to bear the infirmities of the weak and not to please ourselves.” Notice, Paul himself has a position in the debate which divides the Body. Paul identifies with the strong who believe they are free in Christ and therefore do not believe any ought or should should be added to the gospel. Though Paul has summoned both sides in the partisan fight to welcome the other, to walk with them in love, and to bear their burdens, this does not mean Paul regards both parties as correct.

There is a right side in the conflict.

Nevertheless!

Paul subordinates his position to his conviction that believers must treat one another in a manner that makes the gospel intelligible to the wider world. Just so, Paul reinforces his command to “build up the neighbor” by appealing to Christ as our paradigm. But in lifting up Jesus as our exemplar, Paul does not turn to the Gospels. He instead turns to the Old Testament. “For Christ did not please himself,” Paul writes, "but, as it is written, “The reproaches of those who reproached you have fallen upon me.””

The citation is from Psalm 69.

It is a psalm of lament.

It is a psalm of David.

Or so God’s people believed.

Just as the risen Jesus tells the disciples on the road to Emmaus that all the Bible is about him, Paul understands the speaker of Israel’s psalms to be none other than Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim.

Paul’s claim is as colossal as it is subtle. Christ is not simply the subject of the scriptures. Christ is the one who speaks from them. No, Paul’s claim goes even further. Christ speaks from the scriptures to us. Christ speaks from the scriptures to us for us.“For our instruction,” Paul writes in verse four. In other words, according to the apostle Paul not only is Jesus the speaker in the Old Testament, his addressees are you and me. As my teacher Beverly Gaventa comments on this passage:

“Paul’s remark recalls Romans 4.23-24, which asserts that the words of Genesis 15.6 apply both in the case of Abraham and in our own. Unlike Romans 4.23-24, however, Romans 15.4 makes no reference to an earlier addressee, and at least one possible implication of this statement is that Scripture only now has its proper addressees.”

Us.

The Bible is not an artifact.

The scriptures are not simply the record of what God said.

The scriptures are the means by which Christ says.

To us.

For us.

William Stringfellow’s preacher once put the theologian in charge of a Sunday School class for teenage boys. Finding the assigned curriculum shallow and moralistic, Stringfellow did something strange for that congregation. He asked every teenager in the class to secure a Bible. Most of the students ignored him. Nonetheless, Stringfellow opened his own Bible at random to Paul’s Letter to the Romans and just started to read aloud to the teens. During his first class as a Sunday School teacher, all Stringfellow did was to read the epistle in its entirety. He allowed no questions or interruptions.

At the next class on the following Sunday, a boy hoped to foment a rebellion against their new teacher by bringing a case of beer with him to church. But Stringfellow patiently persisted.

Stringfellow writes:

“The essential event each week remained the same— all of us simply heard a reading of the entire Letter to the Romans. It was only after the group had suffered this exercise a dozen or more times, week after week, that the tactic was changed and I proposed that the Letter be then read sentence by sentence, in its given sequence, and that after reading each sentence aloud, we all pause and ask one question: What does this say?

Not, what do I think?

Not, do I agree?

Not, is this relevant to my life and circumstances?

But, straightforwardly, first of all, What is this word?

So we persevered. It was a laborious enterprise. But we did continue, meeting each Sunday, and, as it were, reading and listening to each sentence of Romans, in turn, and asking, What is Christ saying to us?

It was around Christmastime that the change came. The same boy who had brought the case of beer to "class" turned up one afternoon at my tenement in East Harlem. He thought, he said, that I must have plenty of other things to do and would not bother to take time for this "class" or persist in reading the Letter in "class" unless I was convinced there was something important in the Letter. His curiosity was engaged and he had procured a New Testament, stolen he admitted, in order to read the Letter on his own in his privacy.

For the remainder of the afternoon he and I tried to talk with one another about our respective experiences of hearing the Word of God. This tough, brash kid from the streets turned out, in that encounter, to be a most sophisticated exegete, although I am pretty sure that if I ever called him such to his face his impulse would be to hit me for cussing him. Somehow it had lingered in his conscience that the original, indispensable and characteristic question to ask, in reading the Bible, is the very question that seems so seldom to be asked in church or seminary or layman's conferences. Namely, what does this say?”

One Sunday over a decade ago, a worshipper came up to me after worship. She looked angry and utterly discombobulated. The United States was then only a few years into the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and recently the newspapers had broken stories about CIA black sites and the practice of state-sponsored torture. This parishioner’s husband sat on the Senate Intelligence Committee and was a stalwart defender of the administration’s policy of enhanced interrogation. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I was only a few weeks away from her husband tearing me a new one.

“Reverend Jason,” she said in a flustered voice:

“Can I just tell you? I was sitting in my pew, same as any Sunday, and you know what? Some rude, impertinent woman, whom we’ve never spoken to in our lives, came up to us after the service and said to my husband, “I was listening to the scripture today, and the Lord spoke to me.” She said the Lord spoke to her, can you believe the ego on her?! She said, “The Lord spoke to me and the Lord told me to tell you to confess and repent and change your ways.” Can you believe the chutzpah of that woman? Can you even imagine how embarrassing that was— I mean of all the places for that to happen to us, at our church?!”

Bless your heart, I thought.

But I nodded my headed and agreed, “I’m sure it was incredibly embarrassing.”

“Well, what are you going to do about it?!” she insisted.

“Do about it? I’m not going to do anything about it.”

“What do you mean you’re not going to do anything about it?”

“There’s a reason we call them passages of scripture,” I said, “Jesus has this stubborn habit of passing through them and speaking a word. If you don’t like the word that woman heard— well— take it up with the Lord.”

She stormed off.

In due time, neither she nor her husband would speak to me.

That is, until they were spoken to.

Throughout the empire but especially in the heart of it, there was no reliable way for believers to know with certainty that the meat they found in the market had not previously been offered upon Caesar’s pagan altars. “How can we proclaim that Jesus is Lord if we eat meat sacrificed to idols?” the so-called weak in faith anguished. “Will not our manner of living contradict our message? Thus, a segment of Christians in Rome opted for vegetarianism as an aspect of their obedience to Christ. While the argument could have been over any of God’s commandments and their applicability to a believer justified by grace alone, meat was the particular question which vexed the church at Rome.

The apostle Paul devotes over a chapter of his epistle to this dispute, but, notably— surprisingly perhaps— Paul makes no attempt whatsoever to urge the partisans to settle their disagreement. Paul never implores them to find consensus over the issue in question. In wrapping up his discussion of the debate, Paul— though he’s stipulated to his own conviction in the matter— still has not directly instructed the Roman Christians in how to resolve their conflict. Other than laying down the law that believers are to welcome other believers no matter how much they might disagree, Paul has offered no solution for how they might resolve their conflict.

He recommends no concrete measures.He proffers no wisdom or counsel. He gives no practical advice.Yet this is not avoidance!And it is more than sheer pragmatism!About the Bible-stealing boy who had shown up at his front door to discuss Paul’s letter, William Stringfellow recalls:

“Somehow, he had come— reluctantly, against his will, with his customary hostility and suspicion— to confront the Word of God in the Bible in a way very similar to that which he would face any other person. Or rather, the way any other person would face him. And the repeated encounter with the Word of God changed that kid indelibly.”

Quite simply and straightforwardly—

Paul believes the Lord Jesus speaks through the scriptures.Paul submits to the Christians in Rome no practical advice, no concrete guidance because Paul believes it is none other than Lord Jesus who speaks through the scriptures.

On Christ speaking through the scriptures, the theologian Robert Jenson writes:

“God speaks throughout the life of Israel and in her scriptures, and when he speaks this utterance is not another than that same Word who is named Jesus. In the language of the earliest trinitarianism, in persona Verbi: it is the second person of the Trinity, Jesus of Nazareth, who is the persona within the story of Israel.”

The Word is not another utterance than the Word named Jesus.

As the Book of Hebrews says— astonishingly:

“Moses considered abuse suffered for Christ to be greater wealth than the treasures of Egypt.”

Moses suffered for Mary’s boy. A thousand years before Christmas, Moses suffered for Christ. This utterance of the scriptures is not another than that same Word who is named Jesus.

Therefore, Paul believes—