The Paris Review's Blog, page 868

December 3, 2012

Norman Mailer, Sporting Goatee

Star Tracks: Or, a Trip to the LSATs

Like many, I devoted to the recent Petraeus affair only the attention required to make a quip or two. Paula Broadwell and Jill Kelley (already it’s a struggle to remember their names) didn’t linger long in my consciousness as actual people; quickly they became the naughty biographer and Tampa’s answer to Kim Kardashian, respectively. When processing a scandal, the mind makes remarkably fluid conversions from human being to character, and character to joke. Much more difficult is reversing this thinking, as I discovered the day I took a standardized test while seated next to Monica Lewinsky.

This was the fall of 2002—I was twenty-one, living in Brooklyn, and looking to escape the confusion of postcollege life. When I registered to take the law school admissions test at NYU that December, it felt less like choosing a career than like tossing a grappling hook out into the dark, hoping to catch hold of a stable future. Though public interest law seemed a perfectly appropriate path for someone raised on Pacifica Radio and political demonstrations, and though as a kid I’d logged countless hours watching the William Kennedy Smith and O. J. Simpson trials, I had neither an intellectual interest in the law nor any practical understanding of what lawyers did. Something about “briefs,” it seemed.

April Gornick, Untitled, 1996

Since 1964 The Paris Review has commissioned a series of prints and posters by major contemporary artists. Contributing artists have included Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois, Ed Ruscha, and William Bailey. Each print is published in an edition of sixty to two hundred, most of them signed and numbered by the artist. All have been made especially and exclusively for The Paris Review. Many are still available for purchase. Proceeds go to The Paris Review Foundation, established in 2000 to support The Paris Review.

William Styron in Letters

“A great book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end,” explained William Styron in his 1954 Art of Fiction interview. “You live several lives while reading it. Its writer should, too.” Such is the experience in reading Styron’s Selected Letters , edited by Rose Styron and published this week. Alongside major cultural and political events of the latter half of the twentieth century are intimate accounts of family life, depression, writing, frustrations, and friendships.

Of his many lives, Styron may be best remembered in this office for his influence on the early years of The Paris Review. It is awfully fun to see those moments surface in his correspondence, and our selection was made with those moments in mind. Look for a new letter each day this week.

To Dorothy Parker

July 19, 1952 Paris, France

Honeybunch darling—the story is, I believe, coming along just dandy and my pretty much night and day work on it is the main reason I haven’t written you before this. It is now between 11,000 and 12,000 words, which I figure is about two-thirds complete. It has some really good—fine—things in it so far, and I think it will be even better when it’s finished. In fact I think I can say it has some of my best writing in it and will make stories by people like Hemingway and Turgenev pale in comparison. That sounds a bit like what Hemingway would say, doesn’t it? Read More »

Inside Amazon, and Other News

These photos of Amazon’s warehouses are awe-inspiring and terrifying.

Sign a petition to bring filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s work to a wider audience.

The influence of Samuel Greenberg.

The debate over porn in U.S. libraries.

Qatari poet Muhammad ibn al-Dheeb al-Ajami has been sentenced to life in prison for writing in support of the Arab Spring.

November 30, 2012

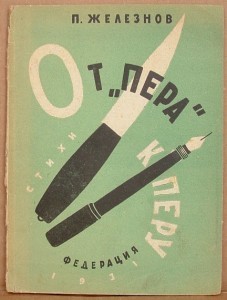

Gulag Tunes

One afternoon in 1943, just before a lunch date with Picasso, Dina Vierny was arrested in Paris. Three months later Picasso received her note, smuggled out with the prison laundry, saying she wouldn’t be able to make it.

One afternoon in 1943, just before a lunch date with Picasso, Dina Vierny was arrested in Paris. Three months later Picasso received her note, smuggled out with the prison laundry, saying she wouldn’t be able to make it.

Vierny, the well-rounded young muse of Maillol’s twilight years, had spent several months in 1940 leading refugees through the mountains from France to Spain. She met her charges at the train station, in her red dress, and they followed her, in silence, all the way to the Spanish border. She was arrested in 1940 and soon released, but by 1943 the Gestapo had the idea that she was some kind of Mata Hari, or perhaps a gold smuggler. During repeated interrogations, over the course of six months, she insisted that she loved hiking (which was true) and that she had been in the mountains buying cooking oil (which was false).

Born in Chisinau, Vierny was raised in a family that was both musical and politically radical. Her father, an Odessa Jew, was a pianist who lost his virginity to an anarchist during exile in Siberia, and her aunts were what Vierny calls “demoiselles nihilistes.” Vierny had sung in the radical performance group Octobre, under the leadership of Jacques Prévert, and with the famous Dimitrieviches, émigré Roma cabaret singers. In prison, she sang for those about to be executed, every Saturday. She had a large repertoire, and she took requests: in her memoirs she says that one young Communist waiting to be shot asked her to sing Edith Piaf through the cell window. She never saw his face.

Read More »In Honor of Jonathan Swift …

On this day in 1667, Jonathan Swift was born. In his honor, we bring you 1902’s Le voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants, by pioneering filmmaker Georges Méliès.

What We’re Loving: Stèles, Cellpoems, Converse

I’ve been nosing around in Robert Hass’s recent collection of essays, What Light Can Do, which itself noses around in such subjects as writing from California, Korean poetry, landscape photography, and Immanuel Kant. There are some pleasurable moments in essays on the poet Ko Un and on Laura McPhee’s photographs of the Salmon River, which winds through the Rockies and into Washington. But I found bliss in Hass’s mediation on Robert Adams’s photographs of the Los Angeles Basin in the late seventies and early eighties. Just before the end, Haas includes a haiku—so appropriate to the city’s spare, industrial haze—whose author he has forgotten: “Cut flowers / in the drainage ditch— / they’re still blooming.” —Nicole Rudick

I’ve been nosing around in Robert Hass’s recent collection of essays, What Light Can Do, which itself noses around in such subjects as writing from California, Korean poetry, landscape photography, and Immanuel Kant. There are some pleasurable moments in essays on the poet Ko Un and on Laura McPhee’s photographs of the Salmon River, which winds through the Rockies and into Washington. But I found bliss in Hass’s mediation on Robert Adams’s photographs of the Los Angeles Basin in the late seventies and early eighties. Just before the end, Haas includes a haiku—so appropriate to the city’s spare, industrial haze—whose author he has forgotten: “Cut flowers / in the drainage ditch— / they’re still blooming.” —Nicole Rudick

What does classical Chinese sound like when imagined by a French modernist poet and translated into English? Victor Segalen, a medical doctor and theorist of exoticism, published the first edition of Stèles in 1912, in Beijing. (A stele is an upright slab with an inscription; a stèle is a genre invented by Segalen.) Each poem in the book is surrounded by a black border and reads—spookily—like a lyric carved into stone: “To fuse everything, from the east of love to the heroic west, from the south facing the Prince to the too-friendly north—to reach the other, fifth, center & Middle // Which is me.” —Robyn Creswell

What does classical Chinese sound like when imagined by a French modernist poet and translated into English? Victor Segalen, a medical doctor and theorist of exoticism, published the first edition of Stèles in 1912, in Beijing. (A stele is an upright slab with an inscription; a stèle is a genre invented by Segalen.) Each poem in the book is surrounded by a black border and reads—spookily—like a lyric carved into stone: “To fuse everything, from the east of love to the heroic west, from the south facing the Prince to the too-friendly north—to reach the other, fifth, center & Middle // Which is me.” —Robyn CreswellOMG Churchill, and Other News

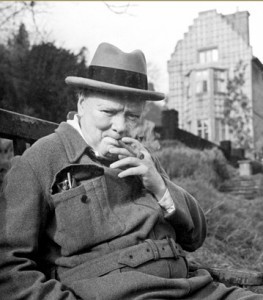

The first use of OMG? This letter to Winston Churchill may be of tremendous significance to the history of texting.

A collection of rare dictionaries is expected to fetch up to one million dollars at auction, although you can snatch up James Caulfield’s Blackguardiana: or, A Dictionary of Rogues, Bawds, Pimps, Whores, Pickpockets, Shoplifters… for three to five thousand dollars.

“A DIY spirit has possessed Atlanta's writers and readers, who are taking literature out of the stuffy confines of the library and into coffeehouses, bars, galleries, and event spaces.”

“In the last couple of days, my book has caused quite a flurry of controversy—or rather, a misrepresentation of it has.” Clearing up the OED scandal.

Kurt Vonnegut's rules for reading fiction: a 1965 term paper assignment.

November 29, 2012

New York, Not Too Long Ago

I hadn’t seen Jake since years ago, when we had met at the Guggenheim before going away to college. I remember only one scene from the encounter: spinning around the museum’s spiraling staircase with our arms spread like wings. When we reached the ground floor, we ran out as fast as we could before anyone could have a word with us about our behavior. I don’t recall talking about France, because I don’t think we really did. I remember just twirling with abandon. He had been the only one to understand my kind of crazy. I wouldn’t see him again for five years.

I hadn’t seen Jake since years ago, when we had met at the Guggenheim before going away to college. I remember only one scene from the encounter: spinning around the museum’s spiraling staircase with our arms spread like wings. When we reached the ground floor, we ran out as fast as we could before anyone could have a word with us about our behavior. I don’t recall talking about France, because I don’t think we really did. I remember just twirling with abandon. He had been the only one to understand my kind of crazy. I wouldn’t see him again for five years.

Our second meeting was in Manhattan at the Odeon restaurant. Jake looked the same as he had in France, though a little taller, a little more handsome, but the same sandy hair and flashing eyes. Except more than ten years of maturity had lent him the calm that had eluded us both back then. He seemed at ease with himself and happy with his work in filmmaking. I couldn’t understand why I hadn’t appreciated his attention as much as I should have when we were young, which meant I’d grown up as well. Instead of fixating romantically on Raees, I should have accepted and cultivated my friendship with Jake—that’s really all it was. Raees was no longer tall and he was an art dealer, having left behind dreams of working in cinema.

“If you’d have asked me then what you’d end up, I thought you’d be a hippie, a free spirit poet,” Jake said as he picked apart a piece of bread. “You were like a flower child obsessed with butterflies—you had this really funny handwriting and drew insects on everything. You had a very beautiful spirit. You were strange, but it didn’t really bother me. I thought it was endearing. You weren’t like the other girls, and they definitely didn’t like you.” He laughed. “Sorry. You know what I mean. It seems as though you’re doing well now.”

“Thank you.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers