The Paris Review's Blog, page 865

December 12, 2012

Zeus, and Other News

On protectionism, e-books, and candlemakers.

Biologist Edward O. Wilson and U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass on science and poetry.

All the best books of 2012 lists that are fit to print, in one place.

Zeus’s affairs, graphically.

The worst word of 2012?

December 11, 2012

Happy Birthday, Huck!

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was first published on December 10, 1884, in England. It remains one of the most-challenged American novels. In its honor, a 1909 Edison film of Mark Twain, taken at his home, Stormfield, in Connecticut.

Gracie and Cyril: An Oral History

Grace Paley was born Gracie Goodside ninety years ago today, and my grandmother still calls her that. My grandmother’s parents separated when the Depression hit: her father lost his job, and couldn’t countenance his wife, a beautician, the household’s only breadwinner. In summer, her mother stuck around the beauty salon, but my grandmother would visit her aunt and uncle in Long Pond, in Mahopac, fifty miles north of the city. Uncle Al was a piano teacher, and one of his students a girl named Grace. Two years older than my grandmother, Cyril, Grace spent the whole summer in Mahopac. Her father, a doctor, built a house there, and he’d bring the family up from their Bronx brownstone, at Hoe Avenue and 172nd Street. My grandmother remembers everything.

Grace Paley was born Gracie Goodside ninety years ago today, and my grandmother still calls her that. My grandmother’s parents separated when the Depression hit: her father lost his job, and couldn’t countenance his wife, a beautician, the household’s only breadwinner. In summer, her mother stuck around the beauty salon, but my grandmother would visit her aunt and uncle in Long Pond, in Mahopac, fifty miles north of the city. Uncle Al was a piano teacher, and one of his students a girl named Grace. Two years older than my grandmother, Cyril, Grace spent the whole summer in Mahopac. Her father, a doctor, built a house there, and he’d bring the family up from their Bronx brownstone, at Hoe Avenue and 172nd Street. My grandmother remembers everything.

Dr. Goodside—Isaac—he had a chauffeur, Saunders. God forbid you use that word—it was a driver. Gracie’s father, he came from a large city in Russia, not the Pale of Settlement. They did not speak Yiddish, they spoke Russian. His great pleasure was when the Italian fruit vendor came, you know, with his truck. He’d come once or twice a week, and Dr. Goodside came to talk to him in his broken Italian. Gracie’s father, he also was a great fan, a lover, of Victor Hugo—and his son, who became an ophthalmologist, was named Victor. Gracie was the youngest, she must have been at least ten years younger than Jeanne, Jeanne after Jean Valjean. And she was named Grace, and her sister said to me, in Italian, it was Grazie—thanks, thanks. Jeanne told me this when she was already teaching, she was much older, and she was married to a child psychologist, a real son of a b—a child psychologist who hated children. They never had children.

Gracie was unusual, she was extremely bright. Every day she was made to read at least an hour, I think she was made to study Russian. And they had a large house in Mahopac, her parents always encouraged kids to come to her house. Her father was a music lover, and he would invite people over to his house, and play music. He had this phenomenal record player. My Uncle Al, the piano player, was such an SOB—he would say, “I’m not going, he doesn’t know anything about music.” But that’s how I knew Gracie, the lessons. Her parents, they wanted us to come to her house, we went there, we played Monopoly. I would see her almost every day—we would go swimming, we would have a hare and hound race, try not to fall for the false trails the guys set up. And we’d discuss politics and sex and stuff, whatever kids at that age discuss. She was the leader because we always went to her house, and she was the one who had ideas, and who could give advice. Even at that age. Wherever you went to meet, it was always at Gracie’s house. All the kids would follow Grace.

The other children—Victor, he was not a talker, and Jeanne, Jeanne was always apologizing. I don’t think they ever really answered the father. And their mother was a quiet woman. Gracie was always the one who was really challenging him.

Fyodor Khitruk, 1917–2012

The pioneering Russian animator Fyodor Khitruk has died at age ninety-five. Perhaps best known for his adaptations of A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh stories, Khitru’s work was often political and avant-garde. 1973’s Island, below, won the Palme d’Or for best short.

Hear That Lonesome Gasket Blow: Part I

In the aisle of the Boeing 737 sardine tin, a wild-eyed, whiskered man—late twenties—held up the smooth flow of Seattle-bound passengers with frantic attempts to stow his carry-on. The impedimenta in question seemed to yours truly a destination-appropriate one: secured to his bulging backpack with yards of duct tape, a skateboard jutted. As he stooped to unwrap the thing, provoking more than a few pursed lips from the jammed queue, he bickered with the flight attendant.

In the aisle of the Boeing 737 sardine tin, a wild-eyed, whiskered man—late twenties—held up the smooth flow of Seattle-bound passengers with frantic attempts to stow his carry-on. The impedimenta in question seemed to yours truly a destination-appropriate one: secured to his bulging backpack with yards of duct tape, a skateboard jutted. As he stooped to unwrap the thing, provoking more than a few pursed lips from the jammed queue, he bickered with the flight attendant.

“Can’t I just keep it in my lap?”

“If you can’t fit it in the overhead compartment, you’ll have to check it plane-side.”

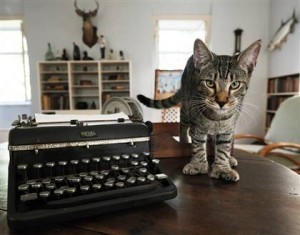

Papa’s Cats, and Other News

A judge has ruled that the (often) six-toed cats who roam the Key West Hemingway House (many direct descendants of Papa’s animals) must be regulated.

“The Snowman is not really about Christmas, it’s about death.” Oh.

Eloise Klein Healy is the first Los Angeles Poet Laureate.

“You have to be lonely to be a writer.” An interview with Edna O’Brien.

“Crafted by local artisans in their fair trade workshop in Chennai, the books are hand-bound and each page is painstakingly screen-printed by hand using traditional Indian dyes, whose fresh earthy scent gently oozes from the gorgeous pages of the finished book.” Watch the making of something beautiful.

December 10, 2012

Brave New Turkeys: We Have a Winner!

For our most recent contest, we asked you, dear readers, to create a festive, possibly dystopian, turkey from Aldous Huxley's handprint. You delivered. Below, without further ado, our favorites.

Free Verses

The online forum was empty when I submitted the essay, my first for Modern & Contemporary American Poetry. It was still early—a few minutes before the midnight deadline, when peer evaluators would then be assigned to post feedback. But not knowing who that peer might be, nor how their public evaluation might portray my work, made the quiet unsettling. Expectant, I awaited review on this naked, vertiginous stage.

The online forum was empty when I submitted the essay, my first for Modern & Contemporary American Poetry. It was still early—a few minutes before the midnight deadline, when peer evaluators would then be assigned to post feedback. But not knowing who that peer might be, nor how their public evaluation might portray my work, made the quiet unsettling. Expectant, I awaited review on this naked, vertiginous stage.

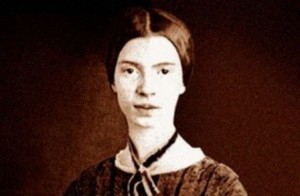

Our assignment for ModPo, as this Coursera version is known, was to close read the Emily Dickinson poem identified by its paradoxical opening line, “I taste a liquor never brewed.” In the poem, ubiquitous intoxicants are absorbed literally out of the moisture in the air. They unhinge our debauched speaker, who before long is “Reeling—thro endless summer days—From inns of Molten Blue.” Describing the scene I invoked soaked clouds crossing the summer sky, befitting a heavy drunken stupor. “Clouded,” I titled the essay.

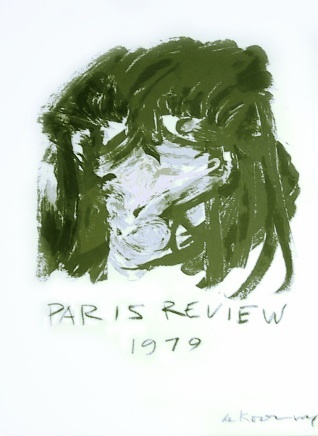

Willem de Kooning, Untitled, 1970

Since 1964 The Paris Review has commissioned a series of prints and posters by major contemporary artists. Contributing artists have included Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois, Ed Ruscha, and William Bailey. Each print is published in an edition of sixty to two hundred, most of them signed and numbered by the artist. All have been made especially and exclusively for The Paris Review. Many are still available for purchase. Proceeds go to The Paris Review Foundation, established in 2000 to support The Paris Review.

Honky-Tonk Hero: Talking with Henry Horenstein

Dolly Parton, Symphony Hall, Boston, MA, 1972.

I first noticed the work of Henry Horenstein when he published his 1987 book, Racing Days, a photographic diary in gritty black and white, compiled largely in the now mostly defunct northeastern thoroughbred circuit. I knew his name at the time to be vaguely familiar from other contexts, though I hadn’t yet made the connection to the body of work he’d done beginning in the 1970s of the world of country music. Seeing the photographs in the new edition of Honky Tonk published together, I finally got it—I’d been admiring these pictures of bluegrass pickers and hillbilly crooners for years without realizing their author. Horenstein captured the extremes of the country-western world over the years, from the Hee Haw familiars onstage at the Grand Ole Opry to old-time cult favorites like the Blue Sky Boys; from seventies country-pop meteors like Jeannie C. Riley to such bona-fide C&W stars as Conway Twitty and Porter Wagoner. But what makes Honky Tonk such a terrific document are the photographs Horenstein took of the places where the music was heard—legendary joints like Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge in Nashville and long-gone venues like the Hillbilly Ranch in Boston—and the regulars inside.

With the republication of Honky Tonk, I spoke to Horenstein, now based in Boston and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, about how a nice young guy from the University of Chicago got involved in documenting what the “King of the Strings” Joe Maphis summed up as the “dim lights, thick smoke, and loud, loud music.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers