The Paris Review's Blog, page 766

November 7, 2013

Kings Have Adorned Her

David Sassoon (seated) and his sons Elias David, Albert (Abdallah), and Sassoon David.

A fortune teller greeted David Sassoon on his way home from synagogue one night in Baghdad and told him to leave at once for India. He would be blessed with immense riches, she said. He was the son of Sheikh Sassoon, chief banker for the Ottoman pasha and nasi, or leader, of Baghdad’s Jewish community. Fleeing the despotic Daud Pasha, who had it out for the wealthy merchant, Sassoon settled in Bombay in 1833, eager to trade under British protection.

Back in the 1830s, Bombay was a port city of seven islands, a relative backwater, but a place where Sassoon could live and conduct business in peace, thanks to the East India Company and in large part to its president, Gerald Aungier. Back in 1668, England, eager to pawn off the Portuguese territory, rented the company the worthless, swampy islands for £10 of gold a year. Aungier saw promise. He moved the company’s Surat operation 165 miles south to Bombay, established courts and added judges, guaranteed religious freedom and individual rights (and loans) to traders and artisans, encouraged racial and religious communities to have spokesmen, and built causeways, docks, and a mint. Aungier created the ethic of equal opportunity that Bombayites would cherish for centuries by urging justice to all “without fear or favor,” says Naresh Fernandes in his smart new biography of Bombay, City Adrift: A Short Biography of Bombay.

November is the fifth anniversary of the bombings at the Taj and Oberoi, two luxury hotels in South Bombay. The much-loved Taj was built by the industrialist Jamshed Tata in 1903, after another hotel turned him away because of his skin color. It’s a hotel that well-off locals grew up in, wandering the halls to admire its magnificent art collection, and lunching at the Sea Lounge, which overlooks the Gateway of India. (It was famously a watering hole for gambler and derbyman Victor Sassoon, David’s great-grandson, who lived at a suite at the Taj in the 1920s and 1940s.)

The targeted murders of Chabad Jews at Nariman House during the 2008 attacks were an odd turn of events. New Jews, known by few, they were not a part of Bombay’s historic landscape. They existed largely to house Israeli travelers, famously fond of long Indian sojourns. (Goa and the Himalayas are Israeli hubs.) The murders signaled not the arrival of anti-Semitism in India proper as much as it underscored the truth that anyone and everyone has always been welcome in Bombay. Though targeting Jews is no fluke anywhere, the real story is the story of Bombay’s Jews, which for all purposes started with David Sassoon. Read More »

One Man’s Trash, and Other News

Discarded books from the Birmingham Public Library become the basis for a series of pieces by local artists.

P. D. James claims to have solved a 1931 cold case in the course of researching a mystery. In 1841, Edgar Allan Poe’s literary gumshoeing was less successful.

The rise of Denglisch—and the introduction of words like shitstorm and cashcow into the German lexicon—is understandably controversial.

Here are some bookish wedding cakes. We feel like that last one is really the cake of a match made in heaven. Mazel tov!

November 6, 2013

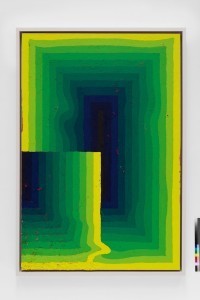

The Subjective Fog: For Julian Hoeber

Pipe Organ, 2007–2013, mixed media.

1. Her Voice in the Night. The disc jockey broadcasts all night from the lighthouse. She back-announces her selections in a murmuring, insinuating tone that, while it wouldn’t disturb a sleeper, might seduce the long-distance trucker or the fisherman on the deck of a boat offshore, some night-shift laborer twiddling the dials of a transistor, barely able to grasp its signal through the wavering night air.

Execution Changes #73B (CS, Q1, LRJ, DC, Q2, LLJ, DC, Q3, ULJ, DC, Q4, ULJ, DC), 2013, acrylic on panel.

2. The Swamp. Yet no, we find we will have to adjust this account. This account is out of order, already entirely misleading, we must begin again; for in this place, there are no long-distance truckers or fishermen on boats. The lighthouse stands not at the juncture of land and sea but at the periphery of a swamp, a vast mire around which the city has erected itself. The lighthouse, once a bold, phallic monument, is dwarfed by skyscrapers, by the cathedral-like domes of vaulted banks, by gleaming condominiums, by monuments of commerce. The lighthouse is only a relic, dragged here by those with an intention to junk it. For it is also the case that the swamp has become the city’s dump. Perhaps the planners once believed the city’s detritus could landfill the mire, stabilize its quicksand core. The swamp might, after the disposal of tonnages of the city’s inconvenient clutter, become ground upon which a pleasant children’s park or a serviceable parking lot could be constructed. But no. The acreage has instead displayed a seemingly infinite capacity for engulfing the rejected material, for devouring structure and remaining nonetheless a moist and murky swamp. Read More »

O Canada

While things may have been tense around Parliament Hill in the last day, let us take a moment to appreciate something lovely: the neo-Gothic wonder that is Canada’s Library of Parliament. Designed by Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones, the 1876 structure is not open to the general public, but is portrayed on the Canadian ten-dollar note.

Punio, Punire

The New York City Marathon has come again, awing, baffling, and intimidating the more sedentary among us with its pursuit of voluntary physical punishment. In a downtown studio a few months ago, another marathon of sorts took place. Ruth Irving was filmed for three hours by the artist Jan Baracz writing the passive present conjugation of the Latin verb “to punish” (punio, punire). I am punished, you are punished … The camera was positioned over Irving’s shoulder as she dipped her calligraphy pen in the inkwell, tracing the words over and over until the page was covered. They had agreed she would just keep writing, creating layers of script on script. Jan looked nervously on, asking her occasionally in his absurdly thick Polish accent if she was okay, which she found irritating after awhile. Her own forced awareness—she couldn’t look away or she would lose her place on the page—was exhausting enough. She had imagined that the difficulty would be at least partly physical—hand cramps or parched throat. But the worst part of it was that she couldn’t stop, sit back and look. As an illustrator, calligrapher, and former architecture student, that’s what she did instinctively, or compulsively. The surveying pause of the artist before the brush lands on the paper. But she was working blind. That was true punishment.

Last fall, Ruth met Jan at a potluck thanksgiving in Brooklyn. They had an immediate, inexplicable rapport in the way only true odd couples can. Five foot ten, pale with raven-black hair, Ruth is from Melbourne, Florida, the daughter of conservative Christians. One of five children, she was homeschooled, wore long skirts, and was not allowed to listen to “music with rhythms.” She describes the environment as “a radical, defy-the-man mixture of religion and hippy anarchism.” She was pulled out of first grade just as she was just learning cursive. “I only knew half the cursive alphabet. It was something I was kind of embarrassed about.” As a result, two years ago, at age twenty-nine, she decided to teach herself to script. “Being homeschooled and being separated, it’s easy to cherish and hold on to, but at the same time it’s really painful,” she says. “Reality is so different from that precious bubble. I wanted to work on communicating with people. Now I’m scripting like everyone who went to school.” She became so adept at it that she was able to find work writing invitations and addressing formal envelopes. Read More »

Margaret Atwood Will Not Blurb Your Book, and Other News

“I blurb only for the dead, these days.” Margaret Atwood’s form rejection poem.

For centuries, Beowulf scholars have translated the epic’s opening line as, “Listen!” But now, Dr. George Walkden argues that “the use of the interrogative pronoun ‘hwæt’ (rhymes with cat) means the first line is not a standalone command but informs the wider exclamatory nature of the sentence which was written by an unknown poet between 1,200 and 1,300 years ago.”

In the past year, ninety-eight small UK publishers went under, a 42 percent rise from the year prior.

We wouldn’t necessarily recommend it, but here is a guide to how to drink like Dorothy Parker.

November 5, 2013

Happy Election Day

“All voting is a sort of gaming, like checkers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it.” —Henry David Thoreau

Reading Through the Leaves

I was recently asked by a Canadian online magazine to visit with the books on my shelves, to find what I’ve hidden in them over the years—old boarding passes, postcards, grocery lists, a love letter never sent. Yes, I found all these things, but mostly I found tree leaves in my books. The editor wanted a picture, fifty or so words, but I kept writing because it bears explaining why I do this—how I take leaves back to my apartment to identify them, compare them to pictures in other books; and once I’ve named them, or sometimes because I’ve failed to, how I feel compelled to keep the specimens—from ash trees, lindens, London planes, honey locusts, and as-yet unknown (to me) trees all over Brooklyn. They are slipped between pages of novels, story and essay collections, a biography, books I have read and often reread, and when I open them later, forgetting myself and the last day I read that book and where, and under what tree, the leaves reenact the fall, not just one leaf but several, all different sorts, falling, or it’s the fragile end of a branch of a pinnate leaves that’s waiting for me, as here in this photo.

I do this in part because Brooklyn, and Brooklyn Heights in particular, where I’ve lived for over twenty years now, has always felt a refuge from a New York City urbanity that is unabashed and demanding, denuded of softness. The streets in Brooklyn Heights in spring, summer, and every year longer into fall are canopied by the copses of trees, reaching for and finally catching each other. These streets feel like invitations to secrets—the right to secrets—to full breaths and quiet even in this city. The other reason I do this, will always do this, owes to my grandfather, who was an arborist, or tree surgeon, in Vermont. Truth be told, he taught me nothing about trees. I was too young to ask, and in my teens, approaching my twenties, when I did think to inquire, he didn’t seem to care to talk about all the trees he’d pruned, saved, and declared beyond saving, especially during the height of the Dutch elm disease in Vermont, when he and his crew carved up hundreds of elms and carted them away for burning.

He wanted to talk about his life before he was married and settled with children and responsibility in Bennington. He’d been a salesman, an itinerant in the 1920s, and lived in rooming houses up and down the East Coast, from New York to Florida, with other young men similarly and mostly happily unmoored. He saw in my youth his own and described men he’d protected from bigger men, men he’d hit, drank with, women who’d been kind, whose faces now were simply the faces of angels, that out of reach. He died when I was nineteen before my sisters and I had all the right questions to ask, so now I can’t stop asking when I look up from my reading on a city bench or stoop: Is that a Chinese scholar tree? Is that one a Norway maple? I asked recently while reading Grace Paley’s collected stories, reading I first did in the nineties and still do fairly often now, for the immediacy and singularity of Paley’s voice, her frankness and energy (partly a gift of city living and loving), and her humor even when confronting human sorrows and disappointments. The book is full of dust from leaves, like the ones pictured here, that want to disintegrate. I won’t let them. I close the book and reseal them—keep the conversation going.

Amy Grace Loyd’s debut novel, The Affairs of Others, was published by Picador on August 27. Loyd is an executive editor at Byliner Inc. and was the fiction and literary editor at Playboy magazine. She worked in The New Yorker’s fiction department and was associate editor for the New York Review Books Classics series. She has been a MacDowell and Yaddo fellow and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Bonfire Night

Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

The Gunpowder treason and plot;

I know of no reason

Why the Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes and his companions

Did the scheme contrive,

To blow the King and Parliament

All up alive.

Threescore barrels, laid below,

To prove old England’s overthrow.

But, by God’s providence, him they catch,

With a dark lantern, lighting a match!

A stick and a stake

For King James’s sake!

If you won’t give me one,

I’ll take two,

The better for me,

And the worse for you.

A rope, a rope, to hang the Pope,

A penn’orth of cheese to choke him,

A pint of beer to wash it down,

And a jolly good fire to burn him.

Holloa, boys! holloa, boys! make the bells ring!

Holloa, boys! holloa boys! God save the King!

Hip, hip, hooor-r-r-ray!

In Conversation

Seven years ago I was walking up Fifth Avenue with David Foster Wallace. He wanted to know what I thought of The Names. That one’s the key, he said, speaking of Don DeLillo’s work like it was a safe which contained its own code. It was hat-and-glove weather. Wallace wore a purple sweatshirt. Where did I get my coat? he asked. That’s a great coat, he said. It was like something James Bond would wear. Had I been to this restaurant before?

We had just walked into Japonica, a sushi restaurant on University Place. Our interview was underway, and Wallace was already several questions ahead of nearly every writer I had ever profiled. Most writers, even the most curious one, don’t ask questions of a journalist. Nor should they, necessarily. They are the ones being interviewed, after all.

Wallace, however, seemed to think in the interrogative mode. He was tall and slightly sweaty, looking like he had just come from a run. But he seemed determined not to intimidate. He was like a big cat pulling out his claws, one question at a time. See, look, I’m not going to be difficult.

Once we got going, though—and there was a propulsive, caffeinated momentum to the way he talked—he returned, constantly, to questions. Had I ever written about my life? It’s hard, right? Are celebrities even the same species as us? Is it possible to show what someone was really like in a profile?

“These nonfiction pieces feel to me like the very hardest thing that I do,” he said, talking about Consider the Lobster, the book he had just published, “because reality is infinite.” And then. “God only knows what you are jotting.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about this encounter lately. For the past fifteen years, I have interviewed a lot of writers. A few hundred—perhaps too many, but why not say yes? Shortly out of college a friend gave me a vintage set of The Paris Review Book of Interviews. They exhaled the flinty musk of a cigar smoker’s home, and were as snappy as the lining of a 1940s dinner jacket. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers